Abstract

Background

Since the 1960s, the federal government has been providing or funding a selection of community-based primary healthcare (PHC) programs on First Nations reserves. A key question is whether local access to PHC can help address health inequities in First Nations on-reserve communities in British Columbia (BC).

Objectives

This paper examines whether hospitalization for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (1) can be used as a proxy measure for the organization of PHC in First Nations reserve areas; and (2) is associated with premature mortality rates.

Methods

In this descriptive correlational study, we used administrative data available through Population Data BC, including demographic and ecological information (i.e. geo-codes indicating location of residence). We used two different measures of hospitalization: rates of episodic hospital care and rates of length of stay. We correlated hospitalization rates with premature mortality rates and the level of care available in First Nations communities, which depends on a federal funding formula based upon community size and, more specifically, the level of isolation from a provincial point of care.

Results

First Nations communities in BC that have local 24/7 access to PHC services have similar rates of hospitalization for ACSC to those living in urban centres. This is demonstrated by the similarities in the strengths of the correlation between premature mortality rates and rates of avoidable hospitalization for conditions treatable in a PHC setting. This is not the case for communities served by a Health Centre (weaker correlation) and for communities serviced by a Health Station or with no on-reserve point of care (no correlation).

Conclusions

Improving access to PHC services in First Nations communities can be associated with a significant reduction in avoidable hospitalization and premature mortality rates. The method we tested is an important tool that could serve health care planning decisions in small communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Closing the gap on health and healthcare inequities is an important goal for primary health care (PHC) reforms [1]. One way to redress these inequities is to address the health and healthcare needs of those who experience the worse health outcomes [2] by strengthening the area of PHC. It is well documented that complex morbidities can be both a cause and a consequence of social exclusion [3]. As an example, those living on First Nations reserves in Canada have higher reported rates of avoidable hospitalizations [4], higher premature mortality rates [5], less developed infrastructure (e.g. roads, housing, access to safe drinking water, etc., [6]), and poorer access to responsive primary healthcare (PHC) and effective continuity of care [7, 8]. The 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples’ report [9, 10] and the recent Truth and Reconciliation report [11] documented historical and contemporary instances of systemic and overt discrimination and racism, which perpetuate health inequities, and called for immediate action.

In this paper, we distinguish between the concepts of PHC and primary care. We define PHC as all interventions intended to prevent the onset of disease (nutrition education, for example), to delay their progression (i.e., HbA1c monitoring for diabetic patients), and to manage complications (i.e., foot care). Comprehensive PHC includes primary care interventions, which refers to out-patient treatments generally provided by a Family Physician, a Nurse Practitioner, or a nurse with an expanded scope of practice. It further includes efforts to address health inequalities through public health interventions, health promotion and preventative care, patient- and community-centred care, and coordination with related social and health interventions.

Since the late 1960s, Canada has been providing access to healthcare to all Canadians under a single payer system. Co-payments and access fees were made illegal in 1984. In theory, all Canadians can therefore access required care. This is true for First Nations living in urban areas or on parcels of traditional lands called “reserves”, which are federally managed for historical reasons (see [12] for a more comprehensive discussion). While First Nations communities have access to a complement of PHC services funded by the federal government and delivered on reserve by either federal or community employees, years of siloed underfunding [13] and jurisdictional fragmentation [7, 8, 14] have created systemic barriers to accessing a broader complement of responsive PHC than what is accessible locally, as well as barriers to continuity of care to services provided off reserve (Family Physicians, specialists, hospital care, diagnostic care are accessed off-reserve and paid by provincial governments). Previous studies conducted in Manitoba have indicated that First Nations communities with access to a broader complement of PHC delivered on reserve in Nursing Stations (these are facilities where resident nurses with an expanded scope of practice deliver PHC) have lower rates of hospitalization for conditions that are manageable in a PHC setting [4]. In order to examine how well PHC services operating on First Nations reserves in BC are able to meet community needs, indicators from already available longitudinal data sources are needed. In this paper, we examine the utility of using hospitalization for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (hACSC) as a potential indicator of equitable access to responsive health care.

Inequities in PHC may arise from a lack of care, untimely access to care, unresponsive care, or differential treatment [15], all of which might result in hACSC and/or premature mortality. Since Weissman et al.’s [16] and Billings and colleagues’ [17] seminal papers, the concept of hACSC has gained popularity in higher and increasingly middle income countries as a measure of the performance of the PHC system (see [18] for a review). Billings et al. defined ACSC as, “(t)hose diagnoses for which timely and effective outpatient [primary] care can help to reduce the risks of hospitalization by either preventing the onset of an illness or conditions, controlling an acute episodic illness or conditions, or managing a chronic disease or condition” ([17], p., 163) While many hospitalizations are justified and therefore unavoidable, disproportionate rates of hACSCs could indicate that the PHC system is either:

-

inaccessible (geographically or economically);

-

ineffective (poor continuity of care, lack of human resources, poor access to diagnosis technologies); or

-

unresponsive (poor quality, alternative motivations, discrimination, lack of cultural safe and trauma-informed care).

Past work about the relationship between PHC and hACSCs remains limited and largely undertheorized. Many studies have focused on conceptual work and debates over the definition of ACSC (for examples, [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]). Some work has shown that the supply of hospital beds is strongly correlated with hACSC. Other work has addressed the relationship between PHC resourcing and hACSC [26, 27]; both showed a strong negative correlation between the funding of PHC and rates of hACSC. Van Loenen and colleagues’ paper on the organizational aspects of PHC related to avoidable hospitalization for chronic conditions [28] highlighted provider continuity, comprehensiveness, multi-disciplinary care, access, and quality of care (adherence to clinical guidelines) as key factors correlated to lower rates of hACSC. They found mixed results with factors related to the organization of PHC (practice type, size, specific services or IT services) and rates of hACSC.

With the exception of Van Loenen and colleagues [29], past research has generally not examined how the organization of the PHC can prevent such hACSC [30]. These international comparisons, however, generated contradictory results [29, 30] suggesting the importance of contextual nuancing [23]. Urban-centric work also dominated research in this field; most studies have focused on large geographical areas and aggregated data across these areas, thereby erasing the specific experience of small rural and remote communities. The few studies that focused on small populations and rural/remote analyses [4, 31,32,33,34,35] have shown that variability in access, quality and responsiveness are important to consider. Finally, few longitudinal studies have been conducted [4, 31, 36] to analyze trends in hACSC over time, or to document the potential impact of policy or organizational shifts on hACSC. Figure 1 summarizes known determinants.

The purpose of this paper is to examine whether hACSC: (1) can be used as a proxy measure for access to responsive PHC in First Nations reserve areas and (2) is associated to premature mortality rate (PMR). This work seems particularly relevant to studies of marginalized and vulnerable populations [4, 31, 37], where outcomes continue to be linked to differential treatment [38,39,40,41].

This work is also timely: On October 1st, 2013, the BC First Nation Health Authority (FNHA) took over a range of responsibilities previously shouldered by a federal agency, namely the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada (FNIHB). It is therefore important to note that all findings presented in this paper predate the transfer of health services to the FNHA and therefore do not reflect subsequent investments or enhancements of PHC on-reserve in British Columbia after October 1, 2013. Still, this work may help inform priority setting for the FNHA.

Methods

The Closing the Gap study is a partnership between the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) and University-based health researchers from the University of Manitoba, the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University and Queens University. Throughout this project, oversight of data interpretation and publications was provided by the FNHA to ensure that the findings were understood in context.

We conducted a secondary analysis of a linked dataset. Multilevel modeling was used in order to capture both the individual (sex, age) and community level characteristics (local access to PHC) that predict hACSC for each resident of a First Nations reserve in BC.

Conceptual framework

In the First Nations context, on-reserve PHC services are funded (and were historically delivered) by FNIHB, whereas services for other Canadians are provided (hospitals, public health) or funded (primary care) by provincial healthcare systems. In the 1980s First Nations communities increasingly began to assume more control over community-based on-reserve health services [42]. In October 2013, the FNHA took over the funding and management of all First Nations health services on behalf of FNIHB. This new model is unprecedented in Canada, and has no equivalent internationally.

First Nation communities in Canada can range from less than 100 to over 15,000 residents. British Columbia’s 199 First Nation communities range from less than 100 to around 3500 residents, with an average of approximately 200 residents. These communities are spread across the province, a territory of just under 950,000km2. While many First Nation communities are located close to provincial community, many more are considered remote and/or isolated, making access to equitable care a challenge.

Table 1 shows the four-level framework used by FNIHB, and inherited by the FNHA, to fund on-reserve health services. Specific services accessible on reserve are associated with each level. Since the late 1980s, this framework has informed funding levels to communities who want to exercise greater control over their local services. Factors that determine the level of services include community size, remoteness, and accessibility of provincial services (proximity, availability of road access, quality of roads i.e. seasonal or year-long, paved or not). Communities considered to have reasonable access to provincial healthcare services in nearby communities are funded to offer screening and preventive services on a part-time basis (Health Stations, n = 42). Communities located within a two-hour drive from provincial services are funded to ensure local access to preventive, screening, and emergency care. These services, delivered through Health Centres (n = 44), focus on primary prevention, with some level of secondary prevention interventions provided by community health nurses and community staff. There is no or limited funding to ensure off-hours coverage, and no funding available for primary care. More isolated communities served by Nursing Stations (n = 10), are funded to ensure local access to screening, prevention, emergency and treatment services on a 24/7 basis, delivered by community health nurses and staff, and primary care nurses with an extended scope of practice. This extended scope of practice requires RNs to receive additional training and certification in remote nursing in order to meet the primary care needs specific to remote communities.

Cohort and First Nations identification

Our sample included all BC residents eligible under the provincial Medical Services Plan (MSP) living on First Nations reserves (estimated at 51,000 FN in BC, [43]). Consolidation File – Registry BC’s administrative data was used to track ways in which residents of First Nations communities have accessed provincial health services over time. In BC, residents must pay an additional tax (premium) dedicated to healthcare. For First Nations, this tax was paid by the federal government (prior to October 1, 2013) and tracked in the BC administrative data. As a result, we were able to use both a proxy for First Nation identification (premium payer) and six-digit postal codes to track First Nations individuals living on reserve in BC.

Variables

A key dependent variable for this study is hACSC. We followed the recommendation of Caminal et al. ([23], p., 246) that “the [ACSC] list should be adapted to the context of each study to guarantee the validity, reliability and magnitude of the hospitalization rate; particularly when health systems are different.” We developed a definition of ACSC, which has been previously validated [4, 31]. We modified the definition based on Billings et al. [17] and the Canadian Institute of Health Information [44] and added components from the Victorian Government of Australia which is more comprehensive [45]. Table 2 shows our final definition using recent studies related to the epidemiological profile of First Nations in MB, ON and BC [5, 46,47,48]. Each condition was defined based on the International Classification of Diseases. We used two different measures of hospitalization: Rates of episodic hospital care: the discrete number of hospitalization episodes from admission to discharge. Hospitalizations were treated as a single episode when readmission to another hospital occurred within one day, to account for transfers from one hospital to another. Rates of length of stay: an average of the number of days in hospital for each episode of care.

The second key dependent variable was premature mortality rate (PMR). Premature mortality is a measure of potential years of life lost before the age of 70 years. Since the deaths of younger people are often preventable, the premature mortality rate is a measure that gives more weight to the death of younger people than to older people [49]. Our final dataset included information on hospitalizations and demographic characteristics of First Nations individuals living on-reserve in BC and community characteristics, including local access to PHC. A key independent variable explored in this study focuses on local access to PHC care.

Sources of data

We used Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), Consolidation file, Census data (1994–2010) and Vital Stats Deaths from files held at Population Data BC [50, 51]. The data contained demographic and ecological information (such as geo-codes indicating location of residence). The DAD contains data on discharges, transfers and deaths of in-patients and day surgery patients from acute care hospitals in BC. The Consolidation file is BC’s central demographics file for research requests. It contains basic demographics such as age and sex, geo-codes indicating location of residence, and registration data. Finally, the Consolidation–Registry data files contains data on medically necessary services provided by fee-for-service practitioners to individuals covered by the Medical Services Plan (MSP), BC’s universal insurance program. It is important to note that we used the Consolidation– Registry data files to aid in the identification of First Nations participants who live on reserve.

The data source on Community information was obtained from a database created by Lavoie based on information in the public domain [52, 53], which contains six-digit postal code information for each on-reserve community, showing the level of care available on reserve (see Table 1); information garnered from First Nations community profiles obtained from the Aboriginal Canada Portal and other public sources; and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada and FNIHB on-reserve population figures. All files were linked by Population Data BC using a unique identifier created specifically for this study. All analyses used anonymized (‘de-identified’) data. All procedures were approved by the University of Manitoba (HS185005 (H2015:064) and the University of British Columbia (H11–01070) Ethics committee and access to data was approved by PopData BC’s data steward.

Data analysis

Table 3 shows the demographic distribution of our population.

We developed a multi-level model to predict hospitalization (separation and length of stay) for hACSC. We used the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method to test for differences in hospital utilization rates for hACSC. GEEs are used as a method for analyzing correlated longitudinal data. This data has measurements (hospitalization) taken over time (1994–2010) on subjects that share common characteristics (age group, sex) living in communities with similar characteristics (level of community control, access to care at the community level). Therefore, one may expect the outcomes for subjects of similar age, sex and community to be correlated over time. The GEE method reflects the correlated structure of the data and allows for valid hypothesis testing results. Measuring trends over time allow us to assess the impact of policy changes on communities over time.

Given that most individuals in any one year were not hospitalized, we used a zero-augmented beta distribution, rather than postulating normality.

Results

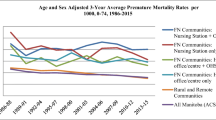

Table 4 shows that at the end of the study, the adjusted PMR were higher in First Nations communities, 2006–10 (5.09) compared to all BC (2.36). While the PMR for communities served by Nursing Stations was 4.01, it was 4.64 and 4.74 for communities served by Health Stations and Health Centres, respectively.

Table 5 shows there was a strong correlation between premature mortality rates and rates of hACSC in communities served by a Nursing Station (where PHC services are provided by nurses) and in other urban BC (where PHC services are generally easily accessible and provided by Family Physicians, as described in the introduction). The correlation was close to 1.0, indicating that as rates of hospitalization drop, so does the premature mortality rate. For Nursing Stations, this means that the dropin rates of hospitalization are related to healthcare needs being met. We found a similar correlation for communities with Nursing Stations and for urban BC, suggesting that having primary care provided in the community, a key feature of Nursing Stations, is key to lowering hACSC. This is particularly true for chronic conditions, where the correlations are the same (0.93 for episodes of care and 0.91 for length of stay).

In contrast to Nursing Stations, communities served by a Health Centre have a lower correlation (0.64 for episodes of care and 0.75 for length of stay). Based on FNIHB’s policy, Health Centres do provide prevention-oriented services, but do not offer community-based primary care (treatment) services. These services are accessed usually from Family Physicians practicing in communities located between 60 and 250 km from the reserve.

We found no correlation between hACSC and premature mortality rates in communities served by Health Stations and in communities with no facility, where residents are expected to go off reserve to access all care.

Discussion

Results from this longitudinal study provide evidence that hACSC can be used as a proxy measure for access to PHC in for First Nations peoples living reserve areas. We suggest that in addition, hACSC could be used as an indicator to measure equity in access to responsive PHC in rural and remote communities. Indeed, our results show a strong correlation between hACSC and premature mortality rate in rural and remote on-reserve communities. We suggest this is an extremely important finding for rural and remote communities whose needs have historically been overshadowed by urban-centric data and where context-relevant evidence is badly needed in order to improve outcomes.

Using hACSC as an indicator, our findings show that Nursing Stations in remote on-reserve communities (and located at a significant distance from other providers of PHC) appear to be providing services nearing PHC services available in urban BC communities. This suggests that in remote on-reserve communities a Nursing Station-like level of services, where local access to PHC is primarily provided by nurses with an expanded scope of practice, may be better equipped to meet PHC needs than the Health Centres and Health Stations we studied. Understandably, local services available across communities are likely to vary and thus more work is needed to examine where Nursing Stations and other communities can learn from each other about aspects of the care that are promising practices. However, these results are similar to what was found in Manitoba, where on-reserve services operate on a framework similar to that used in BC [4]. Therefore, wider integration of resident RNs who have a relationship with community members, and of mechanisms where community members can help shape the service provided, into the organization and delivery of PHC could help to strengthen PHC.

Significant differences remain in the rates of hACSC for First Nations compared to all BC, suggesting that improvements are needed in ensuring responsive, culturally safe and integrated models of care. This will require increased investment, innovation, improvements and enhanced integration of First Nations cultural knowledge and participation in the health care system. First Nations in BC have given this mandate to the FNHA, where such efforts are already underway.

We recognize that this study is observational and as such our results can only document associations. Although there is a temporal element in the predictor-outcome relationship, causal inferences are still somewhat disputable. However, longitudinal studies permit more reliable prediction by borrowing information from all individuals to better predict within-individual change over time. We are using broad categories for on-reserve PHC, which gloss over the variability of services delivered on-reserve. Still, we believe that the approach we developed with the FNHA is the most pragmatic and appropriate method to provide the FNHA a baseline to inform decision-making. A second limitation of this methodology is that hospitalization rates for ACSC reflect the variability in hospitalization criteria, within and between hospitals, as well as healthcare staff decisions [23]. Thirdly, we recognize that our analysis hinges on geocoding where First Nations living on-reserve access primary care. While it is reasonable to assume that First Nations living in remote and remote isolated communities (which are generally served by nursing station or health centre) access primary care primarily on reserve, our experience suggests that residents of semi-isolated and non-isolated communities are more likely to access primary care from a variety of source. We therefore anticipate that our results are less robust for communities served by health offices. Communities with no facility on-reserve are by definition receiving care off-reserve. Finally, we cannot identify all First Nations individuals living on reserve, since the premium paid by the Federal government is only for those who are registered as “status” Indian (i.e those who are recognized as Indians and therefore entitled to specific rights under the Canadian constitution). However, 91.4% of First Nations people living on reserve in BC are status First Nations.

Conclusions

This study adds important findings to a small body of work examining PHC in First Nations communities rural and remote communities. As a proxy measure, hACSC could be considered an indicator of equity in access to PHC in these communities. Moreover, in the absence of data collected from each on-reserve community, hACSC could be used as a proxy measure for the responsiveness of PHC in these communities. In the communities included in this study, PHC was primarily provided by accessing services provided by community health staff and nurses with an expanded scope of practice, and supplemented with off-reserve services as needed.

While our results confirm that local access to PHC results in better outcomes, especially in Nursing Stations, it is likely that a single solution to improve access to PHC for all First Nations in BC will not fit all. Localized solutions, developed in partnership between First Nations communities, the FNHA and the Regional Health Authority are needed. More work is required to understand why local access to a complement of PHC that includes primary care is significant. Possible factors include greater integration between PHC and primary care, when provided by a single team on reserve; better integration of local context in care plans; and better integration with other health services provided on reserve. Additional research to identify which, if any, of these factors may be at play would be helpful.

The analysis we present provides (1) a potential baseline that the FNHA can use in the future to evaluate changes in access to responsive PHC; and (2) direction as to methods the FNHA may utilize in the future to support decision-making. We acknowledge that First Nations communities in BC are diverse, with some located in areas with good access to responsive PHC, some located in remote isolated regions where PHC can be accessed on reserve, and others experiencing considerable challenges accessing limited PHC delivered by Family Physicians off reserve because of road conditions (logging roads, winter conditions). Further, the Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) have historically developed different relationships with First Nations communities located within their catchment areas, with some acknowledging a responsibility to improve access to PHC on reserve, and others having a somewhat less proactive approach. This was particularly true during the period under study (1990–2010). The organization of hospital-based care and PHC also varies in regions, with access to hospital-based acute care being consolidated to larger centres, complemented in some regions by a limited number of smaller community-based hospitals offering limited services. In addition, access to family physicians in BC’s rural and remote communities remains highly variable, and continuity of care is often compromised by turnover and gaps in coverage. Finally, there was a fundamental shift in 2013 following the creation of the FNHA. As a result, the FNHA has since been able to effectively advocate for: shared decision-making in regional planning; the better integration of provincially-provided health services with those provided on reserve; and the integration of First Nation concepts of health and wellness in provincial program delivery [54]. For these reasons we cannot advocate for a single solution to improve access to PHC, even though our data confirms that local access to PHC results in better outcomes. Instead, we recommend localized solutions developed in partnership between First Nations communities, the FNHA and the RHAs.

While the role of PHC in mitigating social exclusion, discrimination, and racism is limited, access to effective and responsive PHC services can be an important lever in softening their impacts and improving outcomes. A recent study by Browne and colleagues [55] demonstrated that there are key dimensions of effective equity-oriented PHC. They argue that the delivery of these key dimensions of care required four complementary approaches: developing partnerships with Indigenous peoples, taking action at all levels, paying attention to local and global histories, and attending to the unintended and potentially harmful consequences of each strategy [56]. We add that for rural and remote environments, effective equity-oriented PHC also includes access (direct and facilitated) to hospital and ongoing specialist care off reserve or via telehealth.

Abbreviations

- ACSC:

-

Ambulatory care sensitive conditions

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DAD:

-

Discharge Abstract Database

- FN:

-

First Nations

- FNHA:

-

First Nations Health Authority

- FNIHB:

-

First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equations

- hACSC:

-

Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions

- MB:

-

Manitoba

- MSP:

-

Medical Services Plan

- ON:

-

Ontario

- PHC:

-

Primary health care

- PMR:

-

Premature mortality rate

- UBC:

-

University of British Columbia

References

World Health Organisation. Primary health care: now more than ever. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2008. http://www.who.int/topics/primary_health_care/en/.

World Health Organisation Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2008. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en.

Bradshaw J, Kemp P, Baldwin S, Rowe A. The drivers of social exclusion: review of the literature for the social exclusion unit in the breaking the cycle series. London: University of York; 2004.

Lavoie JG, Forget EL, Prakash T, Dahl M, Martens PJ, O'Neil JD. Have investments in on-reserve health services and initiatives promoting community control improved First Nations’ health in Manitoba? Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):717–24.

Martens PJ, Bond R, Jebamani L, Burchill C, Roos N, Derksen S, Beaulieu M, Steinbach C, MacWilliam L, Walld R, et al. The health and health care use of registered First Nations people living in Manitoba: a population-based study. Winnipeg; 2002. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/rfn_report.pdf.

Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Reading C. Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2015.

Lavoie JG, Kaufert JM, Browne AJ, Mah S, O'Neil JD. Negotiating barriers, navigating the maze: First Nation peoples’ experience of medical relocation. Canadian Public Administration. 2015;58(2):295–314.

Lavoie JG, Kaufert JM, Browne AJ, O'Neil JD. Managing Matajoosh : determinants of First Nations’ cancer care decisions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(402):1–12.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 1 - Looking forward, looking back. Ottawa; 1996. http://data2.archives.ca/e/e448/e011188230-01.pdf.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 4 - Perspectives and realities. Ottawa; 1996. http://data2.archives.ca/e/e448/e011188230-04.pdf.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation. Ottawa: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. [http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Principles_English_Web.pdf].

Lavoie JG. Medicare and the Care of First Nations, Métis and Inuit. J Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2017;13(3–4):280–98.

Lavoie JG, O’Neil JD, Sanderson L, Elias B, Mignone J, Bartlett J, Forget E, Burton R, Schmeichel C, MacNeil D. The evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit health transfer policy. Winnipeg: Centre for Aboriginal Health Research; 2005.

Lavoie JG, Kornelsen D, Boyer Y, Wylie L. Lost in maps: regionalization and Indigenous health services. HealthcarePapers. 2016;16(1):63–73.

Wong ST, Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, Fridkin A, Smye V, Godwin O, Tu D. Development of health equity indicators in primary health care organizations using a modified Delphi. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114563.

Weissman JS, Gatsonis C, Epstein AM. Rates of avoidable hospitalization by insurance status in Massachusetts and Maryland. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2388–94.

Billings J, Zeital L, Lukomnik J, Carey T, Blank A, Newman L. Impact of socio-economic status on hospital use in new York City. Health Aff. 1993;12:162–73.

Rosano A, Loha CA, Falvo R, van der Zee J, Ricciardi W, Guasticchi G, de Belvis AG. The relationship between avoidable hospitalization and accessibility to primary care: a systematic review. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23(3):356–60.

Purdy S, Griffin T, Salisbury C, Sharp D. Ambulatory care sensitive conditions: terminology and disease coding need to be more specific to aid policy makers and clinicians. Public Health. 2009;123(2):169–73.

Passey ME, Longman JM, Johnston JJ, Jorm L, Ewald D, Morgan GG, Rolfe M, Chalker B. Diagnosing potentially preventable Hospitalisations (DaPPHne): protocol for a mixed-methods data-linkage study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009879.

Nedel FB, Facchini LA, Bastos JL, Martin-Mateo M. Conceptual and methodological aspects in the study of hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16(Suppl 1):1145–54.

Gibbons DC, Bindman AB, Soljak MA, Millett C, Majeed A. Defining primary care sensitive conditions: a necessity for effective primary care delivery? J R Soc Med. 2012;105(10):422–8.

Caminal J, Starfield B, Sanchez E, Casanova C, Morales M. The role of primary care in preventing ambulatory care sensitive conditions. EurJPublic Health. 2004;14(3):246–51.

Sundmacher L, Fischbach D, Schuettig W, Naumann C, Augustin U, Faisst C. Which hospitalisations are ambulatory care-sensitive, to what degree, and how could the rates be reduced? Results of a group consensus study in Germany. Health Policy. 2015;119(11):1415–23.

Longman JM, Passey ME, Ewald DP, Rix E, Morgan GG. Admissions for chronic ambulatory care sensitive conditions - a useful measure of potentially preventable admission? BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:472.

Gibson OR, Segal L, McDermott RA. A systematic review of evidence on the association between hospitalisation for chronic disease related ambulatory care sensitive conditions and primary health care resourcing. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:336.

Korenbrot C, Kao C, Crouch JA. Funding of tribal health programs linked to lower rates of hospitalization for conditions sensitive to ambulatory care. Med Care. 2009;47(1):88–96.

Van Loenen T, van den Berg MJ, Westert GP, Faber MJ. Organizational aspects of primary care related to avoidable hospitalization: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(5):502–16.

Van Loenen T, Faber MJ, Westert GP, Van den Berg MJ. The impact of primary care organization on avoidable hospital admissions for diabetes in 23 countries. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(1):5–12.

Weeks WB, Ventelou B, Paraponaris A. Rates of admission for ambulatory care sensitive conditions in France in 2009-2010: trends, geographic variation, costs, and an international comparison. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(4):453–70.

Lavoie JG, Forget EL, Dahl M, Martens PJ, O'Neil JD. Is it worthwhile to invest in home care? Healthcare policy = Politiques de sante. 2011;6(4):35–48.

Hossain MM, Laditka JN. Using hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions to measure access to primary health care: an application of spatial structural equation modeling. Int J Health Geogr. 2009;8:51.

Ansari Z, Rowe S, Ansari H, Sindall C. Small area analysis of ambulatory care sensitive conditions in Victoria, Australia. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(3):190–200.

Busby J, Purdy S, Hollingworth W. A systematic review of the magnitude and cause of geographic variation in unplanned hospital admission rates and length of stay for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:324.

Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Probst JC. Health care access in rural areas: evidence that hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in the United States may increase with the level of rurality. Health Place. 2009;15(3):731–40.

Saha S, Solotaroff R, Oster A, Bindman AB. Are preventable hospitalizations sensitive to changes in access to primary care? The case of the Oregon Health Plan Med Care. 2007;45(8):712–9.

Stamp KM, Duckett SJ, Fisher DA. Hospital use for potentially preventable conditions in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other Australian populations. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22(6):673–8.

Browne AJ. Discourses influencing nurses’ perceptions of First Nations patients. Can J Nurs Res. 2005;37(4):62–87.

Browne AJ. Clinical encounters between nurses and First Nations women in a Western Canadian hospital. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(10):2165–76.

Paradies Y, Harris R, Anderson I. The impact of racism on Indigenous health in Australia and Aotearoa: towards a research agenda. Casuarina, N.T. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2008.

Shahid S, Finn LD, Thompson SC. Barriers to participation of Aboriginal people in cancer care: communication in the hospital setting. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):574–9.

Lavoie JG, Dwyer J. Implementing Indigenous community control in health care: lessons from Canada. Australian health review: a publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2016;40:453–8.

Statistics Canada. British Columbia. Aboriginal identity (3), registered Indian status (3), age groups (12), sex (3) and area of residence (6) for the population of Canada, provinces and territories, 2006 census - 20% sample data. In: Statistics Canada; 2006.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pan-Canadian primary health care indicators: report 1, Volume 1. Ottawa: Pan-Canadian primary health care indicator development project; 2006.

Victorian Government Department of Human Resources Division. The Victorian ambulatory care sensitive conditions study: opportunities for targeting public health and health services intervention. Victoria: Public Health Division; 2001.

Martens PJ, Sanderson D, Jebamani LS. Health services use of Manitoba First Nations people: is it related to underlying need? CanJPublic Health. 2005;96(Suppl 1):S39–44.

Shah BR, Gunraj N, Hux JE. Markers of access to and quality of primary care for Aboriginal people in Ontario, Canada. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):798–802.

British Columbia Provincial Health Officer. Pathways to Health and Healing - 2nd Report on the Health and Well-being of Aboriginal People in British Columbia. Provincial Health Officer’s Annual Report 2007. Victoria, BC; 2009. [https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/government/ministries-organizations/ministries/health/office-of-indigenous-health/abohlth11-var7.pdf].

The Conference Board of Canada. Premature Mortality Rate: The Conference Board of Canada; 2015. [http://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/details/health/premature-mortality-rate.aspx#ftn1-ref].

British Columbia Ministry of Health. Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). V2. Population Data BC. Data Extract. In. Edited by BC PD. Victoria, BC; 2012.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Discharge abstract database (hospital separations). V2. . In. Edited by BC PD. Victoria BC; 2012.

Lavoie JG, O’Neil J, Sanderson L, Elias B, Mignone J, Bartlett J, et al. The evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit health transfer policy. Manitoba First Nations Centre for Aboriginal Health Research: Winnipeg; 2005.

Natural Resources Canada. First Nations and Inuit Health Branch Facilities. Ottawa: Natural Resources Canada; 2004.

O’Neil JD, Gallagher J, Wylie L, Bingham B, Lavoie JG, Alcock D, Johnson H. Transforming First Nations’ health governance in British Columbia. Int J of Health Governance. 2016;21(4):229–44.

Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, Smye VL, Lavoie J, Littlejohn D, Tu D, Godwin O, Krause M, Khan KB, et al. Closing the health equity gap: evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. IntJEquity Health. 2012;11(1):59.

Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie JG, Smye V, Wong ST, Krause M, Tu D, Godwin O, Khan K, Fridkin A. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16,544:16.

Acknowledgements

The Closing the Gap study was a partnership between the First Nations Health Authority (Ward, Co-PI) and University-based researchers from the University of Manitoba (Lavoie), the University of British Columbia (Wong) and Simon Fraser University (O’Neil). The objective of this CIHR funded [ABH-110955] study was to examine the extent to which the primary healthcare services provided on BC First Nation reserves are meeting needs, using hACSC.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following FNHA individuals: Darius Pruss, Namaste Marsden, Kevin Lowe, Gina Gaspard, Naseam Ahmadi, and Judith Eigenbrod.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canada Institutes of Health Research, Grant #230563. The funder played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data used for this analysis are protected under the privacy policies of the Data Stewards of the BC health administrative data and Population Data BC, and within the terms of the institutional review board approval for this study, and are not publicly available.

Disclaimer

All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this fact sheet are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Population Data BC’s Data Stewards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author meets the authorship requirements as established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals. JL, SW, JO and AW conceived of the study. NI performed the statistical analyses, and JL, SW, JO, MG and AW interpreted this analysis. JL created the first draft of the manuscript. JL, SW, JO, MG and AW contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H11–01070) and the University of Manitoba’s Bannatyne Campus Research Ethics Board (HS18505[H2012:064). Access to the British Columbia health administrative data was secured through Pop Data BC (Lavoie 12–005).

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lavoie, J.G., Wong, S.T., Ibrahim, N. et al. Underutilized and undertheorized: the use of hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions for assessing the extent to which primary healthcare services are meeting needs in British Columbia First Nation communities. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3850-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3850-y