Abstract

Background

Socially disadvantaged groups, such as Aboriginal Australians, tend to have a high prevalence of multiple lifestyle risk factors, increasing the risk of disease and underscoring the need for services to address multiple health behaviours. The aims of this study were to explore, among a socially disadvantaged group of people attending an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS): a) readiness to change health behaviours; b) acceptability of addressing multiple risk factors sequentially or simultaneously; and c) preferred types of support services.

Methods

People attending an ACCHS in regional New South Wales (NSW) completed a touchscreen survey while waiting for their appointment. The survey assessed participant health risk status, which health risks they would like to change, whether they preferred multiple health changes to be made together or separately, and the types of support they would use.

Results

Of the 211 participants who completed the survey, 94 % reported multiple (two or more) health risks. There was a high willingness to change, with 69 % of current smokers wanting to cut down or quit, 51 % of overweight or obese participants wanting to lose weight and 44 % of those using drugs in the last 12 months wanting to stop or cut down. Of participants who wanted to make more than one health change, over half would be willing to make simultaneous or over-lapping health changes. The most popular types of support were help from a doctor or Health Worker and seeing a specialist, with less than a quarter of participants preferring telephone or electronic (internet or smart phone) forms of assistance. The importance of involving family members was also identified.

Conclusions

Strategies addressing multiple health behaviour changes are likely to be acceptable for people attending an ACCHS, but may need to allow flexibility in the choice of initial target behaviour, timing of changes, and the format of support provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Impact of lifestyle risk factors on chronic disease and mortality

Lifestyle risk factors such as smoking, poor nutrition, physical inactivity and excess alcohol are among the leading causes of mortality and disease worldwide [1, 2]. These risk factors tend to be more prevalent among socially disadvantaged and indigenous groups [3–5], for a range of complex cultural and historical reasons [6]. Aboriginal Australians are one example of a socially disadvantaged group for whom key lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation, increased physical activity, reduced alcohol intake and improved nutrition are needed to achieve health equality with the mainstream Australian population [7, 8].

Clustering of health risk behaviours

Health risk behaviours tend to co-occur or cluster together [9–12] with individuals rarely meeting guidelines across multiple behaviours [13]. Socially and economically disadvantaged populations are likely to exhibit a greater number of lifestyle risk factors [14, 15]. For example, Aboriginal Australians visiting a general practitioner were four times more likely to be overweight, daily smokers and to consume alcohol at risky levels than other patients [16]. With the rising burden of chronic and cardiovascular diseases worldwide, there is growing recognition that multiple risk factor intervention should be the cornerstone of primary prevention [14]. The clustering of risk factors among socially disadvantaged groups has particular implications for the workload of primary care teams in deprived areas [14].

Multiple health behaviour change interventions

There is limited but growing evidence supporting the effectiveness of multiple behaviour change interventions [17]. Intervention studies aimed at both diet and physical activity have shown significant improvements for both behaviours [18], while tailored advice for five behaviours including physical activity, fruit, vegetable and fat intake, and smoking cessation was effective in improving dietary behaviours and physical activity, but not smoking [19]. Women who were successful in increasing exercise levels also showed increased efforts to quit smoking [20].

However, as an emerging area of public health research, much remains unknown about multiple health behaviour change, such as the optimal number of behaviours with which to intervene, whether to intervene simultaneously or sequentially, and how to achieve synergies to improve multiple behaviours [21]. A critical issue for health services is the acceptability and effectiveness of multiple behaviour change approaches to care. The potential for multiple behaviour change interventions to overwhelm or discourage participants [22, 23] may be a particular issue for socially disadvantaged populations generally, and for Aboriginal Australians in particular, given that the latter experience higher levels of stressful life events and general psychological distress compared to other Australians [24, 25].

Need for culturally targeted approaches to improving health for disadvantaged and indigenous groups

Understanding consumer perspectives is critical to the design and development of interventions and care models which will achieve high uptake, and therefore, provide a population-level benefit. Consumer perspectives for socially disadvantaged or indigenous groups such as Aboriginal Australians are yet to be explored. Health behaviours among such groups reflect differences in broad influences such as the social environment [26]. For example, smoking is a largely shared and normalised behaviour for many disadvantaged and indigenous communities [27, 28]. Similarly the need for physical activity to be communal or family-oriented, rather than done for the individual alone, has been reported for indigenous populations from Australia [29] and the US [30]. Therefore, tailored approaches to addressing risk behaviours may be needed. Health promotion and prevention strategies aimed at the general population may be less effective in high-risk communities such as Indigenous communities [31], for reasons including the appropriateness of services and support offered [28], use of inappropriate language and messages [31], and limited access to care [32]. A recent review found that culturally enhanced interventions produced better health outcomes than non-enhanced interventions or usual care, for conditions such as diabetes [33]. Given the different social and cultural influences on health risk behaviours [34], generally poorer access to care and lower levels of health literacy [26] of Indigenous and other socially disadvantaged groups compared to less disadvantaged groups, it is critical to gain an understanding of how behavior change might best be supported in these communities.

Need to assess preferences and priorities for health behaviour change

Behavioural medicine literature suggests that people are more likely to achieve behaviour change when they actively participate in the choice of change to be made [35, 36]. Although individual priorities for change may not reflect the risk posed by the behaviour, they reflect perceptions of likely success, confidence, what might be least difficult to change, and readiness to change [36–38]. Stage of change models provide one way to assess an individual’s readiness to change [39]. Although the evidence is not overwhelming [40, 41], interventions matched to stage of change have shown promise for improving behaviours [37, 39]. Intention to change is generally agreed to be among the most proximal influences over behaviour [42], and a lack of intention generally leads to lack of behaviour [43]. While intention does not guarantee action, stages of change are nonetheless important in predicting the likelihood of subsequent changes in behaviour [44]. Of particular relevance to multiple heath behaviour change approaches is evidence suggesting success with changing one behaviour enhances motivation or readiness to change additional behaviours [13].

The development of culturally targeted health interventions addressing some of the major risk factors for socially disadvantaged groups such as Aboriginal Australians would therefore benefit from a better understanding of priorities for behaviour change, readiness to change, and preferences for types of support. The aims of this study were to explore, among participants attending a primary health care service targeting an Aboriginal Community:

-

a)

Readiness to change at risk health behaviours including overweight, smoking, risky alcohol intake, drug use, physical inactivity, poor diet, and depression;

-

b)

The acceptability of addressing multiple risk factors independently, sequentially or simultaneously;

-

c)

The types of support services which would be used to help participants to change risky behaviours, and whether services should be offered to individuals alone, or to individuals as well as their support person or wider support network; and

-

d)

Any significant socio-demographic predictors of stage of change and acceptability of making multiple health behaviour changes.

Methods

Setting and participants

An anonymous, cross-sectional health risk survey was administered on a touch screen laptop to people attending a large Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) in regional New South Wales (NSW) [45]. ACCHSs provide the majority of comprehensive primary health care to Australian Aboriginal communities [46], with approximately 75–85 % of people attending these services being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin [47, 48]. ACCHSs also play a role in community support, special needs programs and advocacy [49]. Informed consent was sought from all participants in the study. Ethics approval for the research was obtained from the University of Newcastle (reference: H-2011-0153) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (reference: 806/11). The study adhered to STROBE guidelines [50].

Participants and procedure

General details of the study procedure have been reported elsewhere [51]. Briefly, AboriginalFootnote 1 and non-Aboriginal adults (≥18 years) attending the ACCHS for a general practitioner (GP) appointment were invited to complete a questionnaire in the waiting room while waiting for their appointment. An Aboriginal Research Assistant (RA) undertook patient recruitment for half of the recruitment period of 2 months in 2013 (with a non-Aboriginal RA undertaking the remaining recruitment). Participants were able to exit the survey if called in for their appointment.

Measures

The touch screen questionnaire included demographic questions and standardised or validated items assessing health risk status including: body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol consumption, level of physical activity, consumption of fruit and vegetables, alcohol intake, drug use, depression and adherence with screening guidelines. Participant weight and height were measured. Current national guidelines or established cut-off scores were used to classify participants as at risk. Details of the measures and cut-offs used to assess risk are included in Additional file 1: Table S1.

A series of questions (presented in Table 1) assessed preferences and priorities for health behaviour change, including stage of change or willingness to change each of the health risks identified above. Participants were asked about any health changes they wanted to make, regardless of their individual risk status. Given the focus on assessing perceptions of multiple health behaviour change, participants were asked specifically about whether they would try to make several health changes at once or one at a time, the support services they would use for making these types of changes, and whether services should be offered to individuals or to individuals as well as members of their wider support network including family or friends. To examine whether particular subgroups might be more or less open to multiple health behaviour change approaches, sociodemographic predictors of willingness to change and preferences for making single or multiple health behaviour changes were also explored.

Stages of change were defined following Prochaska [53] and de Vries [13]. ‘Precontemplation’ (unwilling to change) was defined as either not intending to change the behaviour (Q1: “none of these”) or not within the next 6 months (Q2: “Sometime, but not in the next 6 months”). ‘Contemplation/preparation’ (thinking about changing) included those intending to change the behaviour in the next month or next 2 to 6 months (Q2: “In the next month/ In the next 2–6 months”), and ‘action’ (attempting to change) as those currently changing their behaviour (Q2: “I’m already trying to change…”). Maintenance of behaviour change was not assessed.

Analysis

Any data considered likely to be incorrect for weight (<35 kg or >200 kg) or height (<145 cm or >200 cm) were replaced with missing values. The number of multiple risk factors was calculated for each participant by adding their number of single risks. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the characteristics of consenting and non-consenting participants, and simple proportions used to describe readiness to change, preferences for types of support and other study variables. Any significant predictors of stage of change, acceptability of making multiple health behaviour changes, and preferences for support offered to individuals or wider networks were explored using logistic regression. Predictor variables were gender, age, highest level of education and number of multiple risk factors. A sample size of 200 participants enabled the prevalence of most outcomes to be calculated at the 95 % confidence level with a confidence interval of +/−7 %.

Results

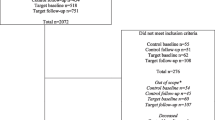

Participants and consent rate

Of 367 participants approached, 245 (67 %) consented to participate. There were no significant differences in the age, gender or Indigenous status of study consenters and non-consenters (all p’s > .05; data not shown). A total of 211 participants completed at least one of the health risk preference questions and were included in analysis. Other participants were called in for their appointment before completing the survey. The demographics of the sample are shown in Table 2. The main source of income for 66 % of the sample was Centrelink (government welfare). Educational levels were also low compared to the general population [54, 55], indicating the majority of the sample experienced relative socioeconomic disadvantage.

Prevalence of risk factors

The prevalence of each risk factor for those with complete data is shown in Fig. 1.

Readiness to change health behaviours

Table 3 shows the number of participants who indicated that they wanted to make at least one of the health changes in the survey, and their stage of change, as a proportion of the total number of participants classified as at risk for each factor.

As shown, smoking had the highest proportion of those at risk wanting to change, with 69 % of current smokers wanting to stop or cut down, and 52 % already trying; followed by weight, with 51 % of those who were overweight or obese wanting to lose weight, and 37 % already trying to do so. The lowest proportion was for those classified as at risk with poor diet, where 23 % indicated wanting to eat more fruit and vegetables and 18 % reported already trying to do this.

For at risk participants across all behaviours, the only significant predictor of readiness to change was the number of multiple risk factors. Those with a greater number of risk factors were more likely to be in the contemplation (already trying to change or wanting to change in the next 1–6 months) than the precontemplation stage (OR = 1.71, SE = 0.30, p = 0.002). Age, gender and level of education were not related to readiness to change.

Acceptability of multiple behaviour change interventions

All survey participants (n = 207) had at least one risk factor, with 94 % having two or more and 67 % three or more multiple risk factors. Approximately half of participants (51 %) reported that there was a single health change that they wanted to make, while 34 % reported wanting to make two or more health changes, and 15 % no health changes.

Of those participants who were contemplating more than one health change (n = 68; data missing for n = 2), 44 % indicated that they would make one change at a time, 32 % chose overlapping changes (‘once I started to get somewhere with one change I would start on the next’), and 24 % indicated they would try to make some or all of the selected health changes at once. None of the selected variables (gender, age, level of education or number of multiple risk factors) were significant predictors of wanting to make changes at once versus one at a time.

Types of support wanted

Any participant who indicated there was at least one health change they wanted to make (n = 176) was asked to select the types of support or help they would use to help them make these changes. The types of support chosen, as a proportion of those selecting at least one health change, are shown in Table 4.

The most common health changes that participants would use advice and support from their GP for included losing weight, getting more exercise, and improving diet. Similarly, face to face support groups would most commonly be used for losing weight, getting more exercise, improving diet and smoking cessation (data not shown).

Support for individuals only or including family and friends

For participants who chose one of the first three types of support (those related to GP or specialist care; n = 146), the majority indicated that they would like this help to be just for themselves (62 %) and about one-third (35 %) for themselves plus a support person, or other members of their family or friends; with 3 % not sure. For participants choosing one of the latter non-clinical types of support (such as support groups or DVDs; n = 128), about half wanted this support to be for themselves only (52 %), or for themselves as well as a support person or other members of their family or friends (45 %), with 3 % were not sure.

Discussion

There was a high prevalence of risk behaviours among our sample, including two-thirds of participants being overweight or having a poor diet, and almost half being physically inactive or current smokers. This is in line with national data for Indigenous Australians [16], and other indigenous and disadvantaged populations internationally [15, 56]. There was a high degree of readiness to change some behaviours, in particular smoking and being overweight. In contrast, few at risk participants were contemplating reducing their alcohol consumption, or increasing their physical activity or fruit and vegetable intake. Of note, the latter two behaviours were among the most highly prevalent, but were associated with the least willingness to change. The vast majority (94 %) of the sample had multiple health risks, but under half reported wanted to change more than one risk factor. Of these, more people preferred the idea of addressing one risk at a time than making more than one change at once. Face to face support services were the most likely to be used, while electronic approaches (such as smart phone apps or websites) were the least popular for making these health changes. Clinical based services (such as GP, specialist) were generally seen as appropriate for individuals, while services such as support groups and educational materials were often preferred to be available to individuals and their wider support network, including a support person or family members and friends.

The majority of smokers in our sample were contemplating or actively trying to quit or cut down (69 %), which is broadly similar to findings for Indigenous Australian smokers from remote Northern Territory communities (58 % contemplating and 17 % attempting to quit) [57] and for women attending an Aboriginal Health Service for ante- or post-natal care (55 % contemplating and 13 % attempting to quit) [58]. Similar rates of cutting down or attempting to quit have been reported for First Nations communities in Canada (46 %; [59]). In contrast to our results, higher proportions of a sample of at risk urban Australian Aboriginal adults were contemplating increased fruit intake (76 %) and physical activity (80 %), compared to increasing vegetable intake (46 %) or smoking cessation (23 %) [7], for reasons which are not clear.

Our sample showed a general lack of readiness to change diet, increase physical activity and reduce alcohol consumption. Less than a quarter of those with a poor diet reported wanting to eat more fruit and vegetables, which has implications for the 51 % of overweight participants reporting wanting to lose weight (although other dietary changes, such as reducing fat intake, were not assessed). Low motivation to change may be due to a lack of awareness of the risks associated with poor diet, physical inactivity or excess alcohol. Over half of the participants from a survey of Aboriginal organisation employees self-reported that they had a ‘healthy diet’, despite half not eating vegetables, and 66 % not eating fruit, on a daily basis [60]. The majority of respondents (72 %) believed that they “…already eat enough [fruit and vegetables]”. Similarly for alcohol, participants in an urban Aboriginal community were not aware of current or previous drinking guidelines and expressed surprise at the low recommended limits [61].

Our sample also showed a general reluctance to address multiple risk factors despite almost all participants having multiple risks. For the 34 % of this sample who indicated that there were multiple health changes they wanted to make, just over half indicated that they would be willing to make some or all of these changes at the same time, or to start on one change and move on to another once they started to get somewhere with the first. No other work exploring preferences for making health changes sequentially or simultaneously for Aboriginal Australians or other socially disadvantaged groups was identified. The most acceptable approach to multiple health behaviour change for this population is likely to be a sequential one in which individuals are able to choose an initial target behaviour. Such an approach may also be feasible for those people reporting only wanting to make one change. For example, success in changing one gateway behaviour may provide increased motivation and self-confidence to attempt more difficult changes [62]. Although individuals may not choose to start with the highest priority behaviour in terms of health benefit, tailoring interventions to individual priorities or readiness may result in greater success in achieving at least one behaviour change, which may in turn increase motivation and confidence to address additional behaviours [37].

The most popular types of support for those contemplating single or multiple health changes included advice and support from a GP or Health Worker, face to face support groups, and seeing a specialist. Support that would be least likely utilised included smart phone apps, web based approaches and telephone support. These preferences also reflect those reported for other Aboriginal communities and socially disadvantaged groups. For example, face to face counselling or group support was preferred for physical activity and smoking among an urban Australian Aboriginal community [7], and few Aboriginal respondents indicated that they would use written materials or telephone support for addressing alcohol problems [61]. Disadvantaged inner city mothers in the UK preferred home visits to telephone for postnatal support [63]. Despite this, there is some evidence that telephone or electronic based approaches can be effective for lower income or indigenous groups [64–66]. These findings have major implications for primary care services, as those preferred types of support are the most costly and time intensive options to deliver. The electronic delivery of support (e.g. via internet or smart phone) would require additional efforts to ensure uptake or access. If not equally accessed or adopted, electronic support initiatives could potentially exacerbate existing health inequalities for already disadvantaged groups.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have explored Aboriginal community preferences for including support persons, family or friends in support strategies for behaviour change. Our results suggest that clinically delivered support is acceptable on an individual level, while community oriented services such as support groups and educational materials would benefit from including a wider network of close family and/or friends. Lack of family support and sense of social isolation have been reported as significant barriers to dietary change for Aboriginal Australians [67]; while some types of physical activity, such as solitary exercise, or done for the benefit of the individual, were associated with feelings of shame or disconnection from others [29]. These principles are likely to apply to other disadvantaged and indigenous groups where, for example, the social environment has also been recognised as a key influence on behaviours [28, 30]. It is therefore likely to be important to offer individuals the choice of having other support persons, including family or close friends, participate in health behaviour change support services or interventions, particularly for those services offered in addition to clinical interactions.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. Firstly our sample was small and drawn from one ACCHS in an inner regional location, which may limit the generalisability of our results, such as to Aboriginal Australians living in urban or remote areas. However, a substantial proportion (43 %) of Aboriginal Australians live in inner or outer regional areas [68]. Secondly, self-report data was used to assess risk status, health priorities and support preferences. Although validated measures of risk assessment were used where possible, many show only moderate sensitivity and specificity, and most have not been specifically validated for use with Indigenous Australians. In addition, the cut-offs used for risk status, although based on national guidelines, set a low threshold for classification as at risk (for example, those consuming less than seven serves of fruit and vegetables per day, those who were overweight as well as obese). Finally, preferences or attitudes do not always predict subsequent behaviour [69]. Therefore, preferences indicated in our survey may not necessarily reflect behaviour, were the preferred types or modes of services to be offered. However, preferences hopefully provide, at a minimum, some indication of the likely acceptability of such services in this setting.

Implications for service delivery

A large proportion of people attending an ACCHS were willing, if not already trying, to make positive changes for their health. Further support services for smoking cessation and weight loss offered in the ACCHSs setting are needed to capitalise on the existing motivation and efforts of people to quit and to lose weight; while efforts to decrease alcohol consumption, and increase fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity may need to first focus on raising awareness of current recommendations and the risks associated with these behaviours. Large benefits may be gained from addressing diet and physical activity, given that these were highly prevalent. GPs or Health Workers were the most preferred source of advice and support for behaviour change, and thus need not feel reluctant in discussing health risk behaviours with clients. Although health care providers need to be aware of the significant stressors and pressures which can potentially drive unhealthy lifestyle choices for indigenous and other socially disadvantaged groups [70], our results indicate this should not be a reason for health care providers to avoid giving health risk advice. The option for support services to include support persons, family members or friends was chosen by a significant proportion of participants and is likely to improve health outcomes.

Given the large proportion of those attending the ACCHS indicating there was only one health change that they wanted to make, a sequential, choice-based strategy within the context of a multiple behaviour change approach may be appropriate for addressing the high prevalence of multiple risks in this population, and other indigenous and socially disadvantaged groups. Initial success with the first choice of behaviour is likely to increase the motivation and confidence of individuals to tackle additional health changes. A long term or stepped care management approach will be needed to ensure that other, potentially more difficult health changes, are kept on the agenda. Preferences for face to face delivery of support services suggest the need for caution with adoption of electronic approaches to health behaviour change, and underscore the need for adequate resourcing of services such as ACCHSs, which provide preventive care for predominantly disadvantaged communities.

Conclusion

Approaches addressing multiple health behaviour changes are likely to be acceptable in ACCHSs as well as other socially disadvantaged primary care settings. However, such approaches may need to allow individual flexibility in choosing an initial target behaviour or behaviours, in timing of subsequent changes, and in the types and format of support provided.

Notes

The term ‘Aboriginal’ is used to refer to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants in this study, following the guidelines of the New South Wales Department of Health, in recognition that Aboriginal people are the original inhabitants of NSW [52].

Abbreviations

- ACCHS(s):

-

Aboriginal community controlled health service(s)

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- GP(s):

-

General practitioner(s)

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Davis A. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380(9859):2224–60.

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–57.

Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75.

Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1703–8.

Najman JM, Toloo G, Siskind V. Socioeconomic disadvantage and changes in health risk behaviours in Australia: 1989–90 to 2001. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(12):976–84.

Brady M. Alcohol policy issues for indigenous people in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2000;27:435.

Adams K, Paase G, Clinch D. Peer-support preferences and readiness-to-change behaviour for chronic disease prevention in an urban indigenous population. Aust Soc Work. 2011;64(1):55–67.

Vos T, Barker B, Begg S, Stanley L, Lopez AD. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres strait islander peoples: the indigenous health gap. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:470–7.

Coups E, Gabil A, Orleans T. Physician screening for multiple behavioural health risk factors. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):34–41.

Fine L, Philogene G, Gramling R, Coups E. Prevalence of multiple chronic disease risk factors: 2001 national health interview survey. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2S):18–24.

Poortinga W. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an english adult population. Prev Med. 2007;44:124–8.

Pronk N, Anderson L, Crain A. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2S):25–33.

de Vries H, Kremers S, Smeets T, Reubsaet A. Clustering of diet, physical activity and smoking and a general willingness to change. Psychol Health. 2008;23(3):265–78.

Ebrahim S, Taylor F, Ward K, Beswick A, Burke M, Davey Smith G. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD001561. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub3.

Kivimäki M, Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Kouvonen A, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Socioeconomic position, co-occurrence of behavior-related risk factors, and coronary heart disease: the Finnish public sector study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(5):874–9.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres strait islander people, an overview 2011. Cat. no. IHW 42. Canberra: AIHW; 2011.

Prochaska JJ, Prochaska JO. A review of multiple health behavior change interventions for primary prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5:208–21.

Vandelanotte C, Reeves MM, Brug J, De Bourdeaudhuij I. A randomized trial of sequential and simultaneous multiple behavior change interventions for physical activity and fat intake. Prev Med. 2008;46(3):232–7.

Smeets TM, Kremers SPJ, De Vries H, Brug J. Effects of tailored feedback on multiple health behaviors. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(2):117–23.

Marcus BH, Albrecht AE, King TK, Parisi AF, Pinto BM, Roberts M, Niaura RS, Abrams DB. The efficacy of exercise as an aid for smoking cessation in women: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(11):1229–34.

Spring B, Moller A, Coons M. Multiple health behaviours: overview and implications. J Public Health. 2012;34(S1):i3–10.

de Vries H, Riet J, Spigt M. Clusters of lifestyle behaviours: results from the Dutch SMILE study. Prev Med. 2008;46:203–8.

Sweet S, Fortier M. Improving physical activity and dietary behaviours with single or multiple health behaviour interventions? A synthesis of meta-analyses and reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(4):1720–43.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres strait islander peoples. Cat. no. IHW 24. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2009.

DiGiacomo M, Davidson P, Davison J, Moore L, Abbott P. Stressful life events, resources and access: key considerations in quitting smoking at an aboriginal medical service. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(2):174–6.

Fiscella K, Williams DR. Health disparities based on socioeconomic inequities: implications for urban health care. Acad Med. 2004;79(12):1139–47.

Johnston V, Thomas D. Smoking behaviours in a remote Australian Indigenous community: the influence of family and other factors. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(11):1708–16.

DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Abbott PA, Davison J, Moore L, Thompson SC. Smoking cessation in indigenous populations of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States: elements of effective interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(2):388–410.

Thompson SJ, Gifford SM, Thorpe L. The social and cultural context of risk and prevention: food and physical activity in an urban Aboriginal community. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(6):725–43.

Coble JD, Rhodes RE. Physical activity and native americans: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):36–46.

Rowley KG, Daniel M, Skinner K, Skinner M, White GA, O’Dea K. Effectiveness of a community-directed healthy lifestyle program in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(2):136–44.

Eakin EG, Bull SS, Glasgow RE, Mason M. Reaching those most in need: a review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(1):26–35.

Barrera Jr M, Castro FG, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(2):196.

Whelan S, Wright DJ. Health services use and lifestyle choices of indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:1–12.

Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):147–55.

Levenkron JC, Greenland P. Patient priorities for behavioral change. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(3):224–9.

Campbell MK, Tessaro I, DeVellis B, Benedict S, Kelsey K, Belton L, Henriquez-Roldan C. Tailoring and targeting a worksite health promotion program to address multiple health behaviors among blue-collar women. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(5):306–13.

Kakafka R, Khan SA, Kaufman D, Mark J. An evidence-based decision aid to help patients set priorities for selecting among multiple health behaviours. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2009;2009:343–7.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. J Addict Nurs. 1993;5(1):2–16.

Cahill K, Lancaster T, Green N. Staged-based interventions for smoking cessation (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;11:CD004492.

Mastellos N, Gunn L, Felix L, Majeed A. Transtheoretical model stages of change for dietary and physical exercise modification in weight loss management for overweight and obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD008066.

Carnegie M, Bauman A, Marshall A, Mohsin M, Westley-Wise V, Booth M. Perceptions of the physical environment, stage of change for physical activity, and walking among Australian adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2002;73(2):146–55.

Sheeran P. Intention—behavior relations: a conceptual and empirical review. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2002;12(1):1–36.

Brug J, Conner M, Harre N, Kremers S, McKellar S, Whitelaw S. The transtheoretical model and stages of change: a critique observations by five commentators on the paper by Adams, J. and white, M. (2004) Why don’t stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Educ Res. 2005;20(2):244–58.

Doctor Connect [http://www.doctorconnect.gov.au/internet/otd/Publishing.nsf/Content/locator]. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Adams M. Close the Gap: Aboriginal community controlled health services; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a right to full participation in decisions affecting their health. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):593.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Healthy for life- Aboriginal community controlled health services: report card. Cat. no. IHW 97. Canberra: AIHW; 2013.

Assessing the health service use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: Interim report of December 2008 [www.health.gov.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/16F7A93D8F578DB4CA2574D7001830E9/$File/John%20Deeble%20Indigenous%20paper%20June%202009.pdf]. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Weightman M. The role of Aboriginal community controlled health services in indigenous health. Australian Med Stud J. 2013;4(1):49–52.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247–51.

Noble NE, Paul CL, Carey ML, Sanson-Fisher RW, Blunden SV, Stewart JM, Conigrave KM. A cross-sectional survey assessing the acceptability and feasibility of self-report electronic data collection about health risks from patients attending an Aboriginal community controlled health service. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14(1):34–42.

NSW Department of Health. Communicating positively: a guide to appropriate Aboriginal terminology. North Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2004.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

Education Across Australia. 4102.0 - Australian Social Trends, 2008 [http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Chapter6002008]. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Education. 2076.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2011 [http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2076.0main+features302011]. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Amparo P, Farr S, Dietz P. Chronic disease risk factors among American Indian/Alaska native women of reproductive age. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(6):A118–28.

Clough AR, Robertson JA, MacLaren DJ. The gap in tobacco use between remote indigenous Australian communities and the Australian population can be closed. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):335.

Heath DL, Panaretto K, Manessis V, Larkins S, Malouf P, Reilly E, Elston J. Factors to consider in smoking interventions for indigenous women. Aust J Prim Health. 2006;12(2):131–6.

Wardman D, Quantz D, Tootoosis J, Khan N. Tobacco cessation drug therapy among Canada’s Aboriginal people. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(5):607–11.

Aitken L, Anderson I, Aitkinson V, Best JD, Briggs P, Calleja J, Charles S, Doyle J, Mohamed J, Patten R, et al. A collaborative cardiovascular program for Aboriginal and Torres strait islander people in the Goulburn-Murray region: development and risk factor screening at indigenous community organisations. Aust J Prim Health. 2007;13(1):9–17.

Conigrave K, Freeman B, Caroll T, Simpson L, Lee K, Wade V, Kiel K, Ella S, Becker K, Freeburn B. The Alcohol Awareness project: community education and brief intervention in an urban Aboriginal setting.

Emmons KM, Marcus BH, Linnan L, Rossi JS, Abrams DB. Mechanisms in multiple risk factor interventions: smoking, physical-activity, and dietary-fat intake among manufacturing workers. Prev Med. 1994;23(4):481–9.

Wiggins M, Oakley A, Roberts I, Turner H, Rajan L, Austerberry H, …, Barker M. Postnatal support for mothers living in disadvantaged inner city areas: a randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005. 59(4):288–95

Carson K, Brinn M, Peters M, Veale A, Esterman A, Smith B. Interventions for smoking cessation in indigenous populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD009046. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009046.pub2.

Michie S, Jochelson K, Markham WA, Bridle C. Low income groups and behaviour change interventions: a review of intervention content, effectiveness and theoretical frameworks. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.078725.

O’Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K, Bauman AE. Characteristics of participants in Australia’s Get healthy telephone-based lifestyle information and coaching service: reaching disadvantaged communities and those most at need. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(6):1097–106.

Abbott P, Davison J, Moore L, Rubinstein R. Barriers and enhancers to dietary behaviour change for Aboriginal people attending a diabetes cooking course. Health Promot J Austr. 2010;21(1):33–8.

4704.0 - The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Oct 2010 [http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/lookup/4704.0Chapter210Oct+2010]. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Kraus SJ. Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21(1):58.

Wood L, France K, Hunt K, Eades S, Slack-Smith L. Indigenous women and smoking during pregnancy: knowledge, cultural contexts and barriers to cessation. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2378–89.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all the staff (in particular the CEOs, Leanne Dryden, Steve Terrey, Jill McDonald, and the reception staff) who supported this research, and to the participants who kindly completed the survey and made this study possible.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by a Strategic Research Partnership Grant from Cancer Council NSW to the Newcastle Cancer Control Collaborative, and a NSW Health Drug and Alcohol Research Grant. Infrastructure support was provided by the Hunter Medical Research Institute. A/Prof Christine Paul is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship. These funding bodies had no involvement in the conduct of the research or the preparation of this manuscript.

Availability of the data and materials

Data is available from the corresponding author on request.

Authors’ contributions

NN developed the study materials, conducted data collection, undertook analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. CP was responsible for study conception and design, provided support during data collection, and assisted with drafting and revision of the manuscript. RSF contributed to the overall study design and development of survey items, and assisted with drafting and revision of the manuscript. HT, KC and NT provided feedback on study design and specific study materials, NT facilitated and provided assistance with data collection, and all provided critical feedback and revision of the manuscript. All authors have given their approval for this version of the manuscript to be published.

Authors’ information

NN, B.Psych (Hons), is a PhD candidate and Research Assistant with the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour at the University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute. Her post-graduate research focuses on primary care and chronic disease issues among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, including exploring the clustering patterns of modifiable health risk behaviours and provision of appropriate support services. Natasha is also interested in preventive health issues and risk behaviours among other socially disadvantaged and high risk populations more broadly. CP, PhD, is an Associate Professor with the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour at the University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute. A/Prof Paul is experienced in the development and evaluation of strategies for achieving behavioural change on an individual, system and population level. Her research interests include cancer prevention and tobacco control, social disadvantage, chronic disease and health service delivery. Her recent work involves applying behavioural approaches to multi-site intervention studies in the fields of diabetes care, stroke treatment, and improving health among disadvantaged groups including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. RSF, PhD, is internationally recognised as a leader in health behaviour research. His work is known for successfully combining behavioural and public health approaches to health promotion, health service evaluation and cancer control. L/Prof Sanson-Fisher’s research interests include changing health care providers clinical behaviour so that it more closely reflects evidence based practice, and the development, implementation and evaluation of interventions aimed at improving health outcomes for vulnerable population groups. HT, PhD, is a Senior Research Officer with the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour at the University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute. Dr Turon has post-graduate research experience in the fields of cognitive psychology, behavioural change, information provision and memory retention. Her current research interests include evaluation of effective communication messages to increase awareness about organ donation, psychosocial wellbeing of haematological cancer patients, and examining variations in care for cancer patients across treatment centres, with a focus on differentiating between the impacts of individual and treatment centre level variables. NT, B.AppSci, is a health clinician and Senior Project Officer with the Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health at the University of Newcastle. Nicole is one of the few Aboriginal community nutritionists in Australia. Nicole was recently recognised for her work at the grassroots level in improving health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across the State. Her research includes implementation and evaluation of interventions aimed at improving nutrition and physical activity among Aboriginal children and young adolescents. KC, FAChAM, FAFPHM, PhD, is an addiction medicine specialist and public health physician at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. There she provides treatment for alcohol or drug use disorders in outpatient and inpatient settings. Kate is a conjoint Professor at the University of Sydney and has acted as an editor of two clinical texts “Addiction Medicine” and “The Handbook for Aboriginal Alcohol and Drug Work”. She has received the Senior Scientist Award of the Australasian Professional Society on Alcohol and other Drugs. Kate has had the opportunity to work in partnership with Aboriginal communities in urban, regional and remote Australia.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this research was obtained from the University of Newcastle (reference: H-2011-0153) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (reference: 806/11). Informed consent was sought from all participants in the study and consent to participate was implied by completion of the touchscreen survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Includes details of the measures used to assess risk factors in the health risk survey, as well as the cut-offs used to define risk status. (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Noble, N., Paul, C., Sanson-Fisher, R. et al. Ready, set, go: a cross-sectional survey to understand priorities and preferences for multiple health behaviour change in a highly disadvantaged group. BMC Health Serv Res 16, 488 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1701-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1701-2