Abstract

Background

Poor adherence to medication regimens increases adverse outcomes for patients with Type 2 diabetes. Improving medication adherence is a growing priority for clinicians and health care systems. We examine the differences between patient and provider understandings of barriers to medication adherence for Type 2 diabetes patients.

Methods

We searched systematically for empirical qualitative studies on the topic of barriers to medication adherence among Type 2 diabetes patients published between 2002–2013; 86 empirical qualitative studies qualified for inclusion. Following qualitative meta-synthesis methods, we coded and analyzed thematically the findings from studies, integrating and comparing findings across studies to yield a synthetic interpretation and new insights from this body of research.

Results

We identify 7 categories of barriers: (1) emotional experiences as positive and negative motivators to adherence, (2) intentional non-compliance, (3) patient-provider relationship and communication, (4) information and knowledge, (5) medication administration, (6) social and cultural beliefs, and (7) financial issues. Patients and providers express different understandings of what patients require to improve adherence. Health beliefs, life context and lay understandings all inform patients’ accounts. They describe barriers in terms of difficulties adapting medication regimens to their lifestyles and daily routines. In contrast, providers' understandings of patients poor medication adherence behaviors focus on patients’ presumed needs for more information about the physiological and biomedical aspect of diabetes.

Conclusions

This study highlights key discrepancies between patients’ and providers’ understandings of barriers to medication adherence. These misunderstandings span the many cultural and care contexts represented by 86 qualitative studies. Counseling and interventions aimed at improving medication adherence among Type 2 diabetes might become more effective through better integration of the patient’s perspective and values concerning adherence difficulties and solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Medication adherence plays an important role in the clinical care of Type 2 diabetes because it directly contributes to the effectiveness of patients’ treatment and wellbeing [1, 2]. Diabetes affects a growing number of patients, and represents one of the primary causes of death among adult individuals [3, 4]. Diabetes affects about 382 million people worldwide, of which 85 % to 95 % accountable to Type 2 diabetes in high-income countries, as well as in low-and-middle income countries [4]. The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes grows steadily, due to environmental and behavioural factors such as economic growth, urbanization, ageing populations, poor dietary habits, and decreased physical activity [4, 5].

Diabetes is a disease with no specific cure and a demanding self-management regimen [4, 5]. It is a progressive condition that requires continuous management as well as patient and provider collaboration in order to avoid both short-term and long-term life-threatening complications [4, 5]. Diabetes management targets optimal blood glucose levels, thereby preventing the onset and progression of diabetes-related complications including cardiovascular complications, nerve damage, kidney failure, eye disease, and diabetic foot, all factors that can eventually lead to death [3–5]. Effective Type 2 diabetes management can include adherence to medication regimens (hypoglycaemic oral tablets and/or insulin injections), as well as adjustment of specific life-style behaviours, such as increased physical activity, adherence to specific dietary regimens, smoking cessation, and strict monitoring of blood glucose levels [1, 5].

Although good glycemic control can help to prevent such complications, diabetes treatment regimens can be complex. Patients often do not adhere to medication regimens [1, 2, 6–12]. Non-adherence represents burdens both for patients and for healthcare systems by increasing morbidity and mortality, reducing quality of life, and raising healthcare costs [1, 2, 6, 9–11]. Traditionally, non-adherence behaviours stem from a patient’s failure or refusal to comply with the prescribed medication instructions due to a lack of knowledge or lack of motivation [7, 9–11, 13]. In this tradition, researchers investigate why patients failed to comply with providers’ recommendations [7, 13–15]. However, new perspectives on this topic acknowledge the beneficial effects on treatment outcomes of a more collaborative relationship between patient and provider that focuses on concordance rather than adherence or compliance with medication regimens. This perspective recognizes adherence as resulting from a broad set of factors, and linked to more than just knowledge and motivation [7, 10, 13, 16]. The shift towards a more patient-centered model of care recognizes the “empowered autonomy” of patients as equal and active partners in care, contributing experiential knowledge to the decision-making process of care [7, 10, 13, 16]. A patient-centered approach, then, encourages the use of a negotiated model of care to foster concordant treatment behaviours [7, 9–11, 13, 16].

Acknowledging patients’ voices in the treatment decision-making process requires deeper understanding of patients’ views of medications, and how these might differ from the assumptions or values of healthcare providers. This manuscript synthesizes numerous qualitative studies to distil broadly relevant and applicable insights into better medication adherence. We focus on patient and provider perceptions of patients’ barriers to medication adherence, amongst community-dwelling adults with Type 2 diabetes. In particular, our research question asks: what barriers to medication adherence Type 2 diabetes patients and their providers identify? This synthesis includes 73 studies which include patient perspectives, 9 studies which include provider perspectives and 4 studies which include both patient and provider perspectives. Findings reveal the full spectrum of barriers and facilitators patients face in using diabetes medications as directed. The four existing studies comparing both patient and providers perspectives highlight some key incongruencies in attitudes and perceptions towards medication adherence barriers [17–20]. Research findings reveal discrepancies between providers’ conceptualization of quality of health as opposed to the patient’s idea of overall well-being, as well as different attitudes to the risk of medication adverse effects [17–20]. However, most of these studies address particular ethnic populations, or patient populations with specific co-morbid conditions, or specific healthcare professional services, without providing an overall picture of the differences between patients and providers. This study adds to the under-researched literature on the differing perspectives on medication adherence between patients and providers. Further, analysis of the differences between patient and provider perspectives highlights areas for developing more patient-centered practices to improve medication adherence.

The topic of this study was informed by the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee’s Expert Advisory Panel on Community Care for Type 2 Diabetes project on the improvement of access to, and quality of, diabetes services and care to enhance prevention and improving diabetes management. This agency commissioned a report on patient perspectives on barriers and facilitators to medication adherence. During our analysis of this data, we noted the discrepancies between patient and provider perspectives and so returned to our data to perform a secondary analysis on the current topic.

Methods

We provided the methods for the search in detail in a technical report written with the same data on medication adherence among Type 2 diabetes patients for the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee’s Expert Advisory Panel [21]. The report focused only on patients’ perspectives to barriers and facilitators of medication adherence. We summarize those methods here.

Literature search

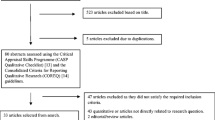

Figure 1 summarizes the systematic bibliographic search process. We developed a search filter that combined existing published qualitative filters [22–24] with a diabetes-topic-specific filter. Because qualitative methodology filters have poor specificity, we used exclusionary terms to improve the precision of the filter (we describe details elsewhere, available as a CHEPA Working Paper online at http://www.chepa.org/research-papers/working-papers or from corresponding author upon request) [21]. We searched OVID MEDLINE, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing, Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and ISI Web of Science Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), for studies published from January 1, 2002 to August 10, 2013. 2002 was chosen to produce a manageable number of results, and to reflect that the knowledge before this time was well summarized in the WHO’s 2003 report on medication adherence [1]. We included papers in English, available online through McMaster University’s library system, reporting primary qualitative empirical research, involved or addressed adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (including papers with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes), and conducted in Canada, the USA, Europe, Australia, or New Zealand. These countries were chosen because they have similar levels of resource availability (e.g. diabetes health care, medications) to Canada. When papers were not available through the library system of our large, research-intensive university we made attempts to contact the authors to request a copy of the paper through information available in the abstract/citation or a Google search. Only 1 paper was unavailable after these attempts (as shown in Fig. 1). We excluded papers that were unpublished (e.g., reports, theses), not in English, reported secondary or non-empirical studies, used non-qualitative methods, or were off-topic (that is, not addressing the topic of medication adherence). Our search terms were designed to find qualitative studies about diabetes; further refinements of the search (e.g. topic of medication adherence, like health care context) were performed manually. Examples of exclusionary terms include “coefficient” and “p value”. At least two reviewers independently reviewed titles, abstracts, and later full papers to determine eligibility. We reviewed titles and abstracts to identify findings related to medication adherence, medication and self-management. We then reviewed the full text of the papers before inclusion to identify any findings related to medication adherence. Data extraction was performed by two authors; all authors participated in analysis. Discrepancies were resolved through conversation between the two authors with a third author participating when an additional perspective was needed. Studies that included either Type 2 diabetes patients OR both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes patients were included. When analyzing studies that included participants with both types of diabetes, we considered the data related to Type 2 diabetes patients when the authors provided this separately. When no distinction was made between the data from Type 1 and 2 participants, we included all data. We included a total of 86 papers in this synthesis, summarized in Table 1. For a detailed list and description of the main focus of each study see Table 2.

We used the integrative technique of qualitative meta-synthesis to analyze our data [25–27]. Qualitative meta-synthesis aims to both summarize a range of findings across studies while retaining the original meaning and to compare and contrast findings across studies to produce a new integrative interpretation [28]. Analytical integrative meta-synthesis combines and synthesizes findings in new interpretative ways, while preserving the differences and complexities of the topic under study. Congruent with this meta-synthesis methodology, we started with a pre-defined topic and research question, which guided data collection, extraction of findings, and analysis. We retrieved all qualitative research relevant to this research question. Critical appraisal remains controversial for qualitative research methodology, in part because there is a lack of consensus in the field about what constitutes high quality research [29]. Procedural detail is typically under-reported, but even when reported and achieved, methodological procedures do not always guarantee to useful results [27, 29]. Accordingly, we followed current conventions in qualitative meta-synthesis and neither appraised nor excluded papers on the basis of any superficial indicators of quality other than excluding papers which did not provide evidence to support their stated findings [25, 26, 28, 30–34].

The data extraction phase involved identifying findings relevant to the topic, focusing on the authors’ secondary interpretations – i.e., the authors’ “data-driven and integrated discoveries, judgments, and/or pronouncements researchers offer about the phenomena, events, or cases under investigation” [26]. Primary data makes ad hoc appearances in qualitative reports; while we did not focus our analysis on these excerpts per se, we did extract participant quotes when useful for illustrative purposes.

We analyzed our data using a staged coding process similar to grounded theory, [35, 36] breaking findings into their component concepts and then grouping and re-grouping those findings across studies according to inductively identified themes. First, FM, MV, and DH coded the same sources of data (the 86 articles) and identified the preliminary categories. Categories were formed based on both prevalence of information across a large number of studies and usefulness or importance of information in a smaller number of studies. These categories provided the foundation for our interpretive insights of medication adherence across the body of research. We used a constant comparative and iterative approach, in which we compared preliminary categories with the research findings, raw data excerpts, and co-investigators’ interpretations of the studies. FM, MV, and DH met regularly to discuss the analytical findings and the next analytical steps. Finally, all the authors jointly negotiated the final emerging analytical themes.

All authors participated in the overall analytical process, meeting regularly to discuss the iterative process of analysis, compare findings and interpretations, and decide how to move forward.

Results

The 86 included studies involved 2797 individuals with Type 2 diabetes, 40 caregivers, and 356 clinicians. The integrative analysis of these studies provides rich findings concerning how patients and providers perceive barriers to medication adherence. We organize these findings into 7 categories of barriers and facilitators: (1) emotional experiences as positive and negative motivators to adherence, (2) intentional non-compliance, (3) patient-provider relationship and communication, (4) information and knowledge, (5) medication administration, (6) social and cultural beliefs, and (7) financial issues. For each, we describe how patients and providers understand the barriers, and highlight key areas of congruent vs. divergent understandings.

Emotions increasing and decreasing adherence

Both positive and negative emotions can impair or promote medication adherence. Positive emotions, such as experiencing positive health benefits of insulin treatment [37–41], can reinforce self-reported feelings of empowerment [37–41], and the ability to follow-through with self-care [40, 42–44]. Emotional and social support promote a sense of self-efficacy and commitment to lifestyle changes [22, 45–52], encouraging patients to do better and stay “on track” [46, 48–58].

Negative emotions such as fear, self-blame, guilt, shock, helplessness, and frustration can also either raise or lower adherence. Patients frightened by symptoms returning, early death, and potential complications of diabetes sometimes become more serious about medication adherence [41, 47, 58–66]. Observing the suffering of others with diabetes complications can motivate patients to adhere strictly to their own treatments [51, 59, 67].

However, some patients prefer providers to emphasize the potential benefits of adhering, rather than the risks of non-compliance [41, 43, 44, 58]. Those with increasing complications and intensifying treatment sometimes feel they have already failed at managing the disease, creating a “vicious circle of low motivation” [41, 61, 68–74]. Distress – whether from diabetes or other sources – can also demotivate medication adherence [71, 75, 76]. Co-morbid conditions, such as heart disease, hypertension, depression, kidney failures, decreasing sight [22, 44, 50, 57, 66, 68, 77–79] can also lead to stress and complicate self-management practices [17, 22, 50, 57, 58, 66, 68, 77–80]. However, co-morbidities can have the opposite effect of increasing motivation as successful self-management promotes self-confidence [44, 45, 52, 58, 81].

Healthcare professionals peripherally address the theme of emotions in conversations of motivation, explicitly attributing poor adherence to patients’ lack of motivation, even when providers do not explicitly discuss the impact of emotions on motivation [75, 82–85].

While patients’ motives are deep rooted and difficult to modify [85], providers echo patients’ perspectives on the influence of symptoms in adherence behaviours [78, 82]. Asymptomatic patients adhere less consistently to medication [58, 83, 86]. In contrast, patients who feel unwell, thus frightened, convert to insulin therapy more willingly [86]. Some providers use insulin as a threat to motivate their patients to improve adherence [41, 58]. Providers, as patients, also recognize that symptom improvement motivates patients [82], acknowledging the motivating effect of positive emotions related to empowerment and success [78].

Intentional non-adherence

Some patients intentionally and purposefully do not follow their medication regimens. We conceptualize intentional non-adherence as the patients’ refusal to adhere to a specific medication regimen. Patients’ beliefs and attitudes toward the health care system can promote informed and not informed intentional non-compliant behaviours [17, 43, 50, 78, 87–89].

Intentional non-adherence sometimes results from denial about the seriousness of diabetes [47, 57, 65, 68, 77, 90]. Denial of the severity of diabetes may relate to the belief that “everybody’s got it” [90], or to the underlying scepticism and lack of trust about the effectiveness of the treatment coupled with the fear that the prescribed medication is unnecessary, unhealthy, or dangerous [44, 50, 80, 89, 91]. Most commonly patients decide not to adhere to medication regimens as an effort to avoid side effects [50, 67, 68, 78, 79, 89, 92–94]. This type of intentional non-compliance often takes a trial and error approach, with the patient self-adjusting medication (i.e. doses and timings) [17].

Providers in several studies describe a scenario where patients agree to take the medication, but then do not follow through for unclear reasons despite provider’s “best detective work” [75, 95]. Providers ascribe different motivations to this behaviour, including cultural motives (e.g. preference for traditional medication), financial constraints, depression, and poor cognitive ability [17, 85]. However, we found no evidence that providers recognize that intentional non-adherence may result from a patient's attempt to mitigate unpleasant medication side effects.

Patient-provider relationship and communication

Many studies address the nature of the relationship between patients and health care providers and how this relationship affects medication adherence and self-management practices either positively or negatively [17–20, 37–44, 48–60, 62, 64–70, 72, 73, 75, 76, 78, 81, 89, 91, 93, 94, 96–109]. Patients describe their relationship with their provider in relation to several types of facilitators, including health care professionals’ support, collaboration and improved communication strategies [17–19, 38, 39, 41–44, 48–54, 57–59, 62, 64–70, 72, 73, 76, 78, 81, 93, 94, 96–105]. However, many patients remark on the disconnect between treatment recommendations and their everyday life, as well as perceptions of lack of support, communication barriers, challenges of working with culturally insensitive providers, and barriers to accessing health care providers, such as time constraints during visits [17, 18, 20, 37–40, 42–44, 48, 50, 52–56, 59, 60, 62, 64, 68–70, 72, 73, 75, 76, 78, 81, 89, 91, 93, 94, 96–99, 101, 102, 105–109]. In particular, patients describe a desire to be “perceived as persons, not illnesses” [66, 75, 81]. Without the understanding of patient’s life contextual factors, providers may set unrealistic targets, which patients deem impossible, thus frustrating [17, 44, 69, 75, 91, 99]. Patients attribute providers’ unrealistic expectations to a lack of support or disinterest, which results in feelings of distrust [17, 18, 44, 52, 59, 69, 75, 91, 96, 97, 99, 107]. Many patients report hope for a collaborative relationship based on mutual trust and agreement between patient and provider, which would allow them to openly discuss their challenges and concerns with the providers [17, 18, 39, 41–44, 48, 50, 52, 57, 58, 66–68, 70, 72, 73, 78, 92–94, 96, 100–102]. Both non-marginalized and socially and culturally marginalized patients, such as indigenous groups, immigrants, and visible minorities stress the importance of their relationship with the provider. Although each population group focuses on different aspects of such relationships, both groups place great value on the patient-physician relationship as a beneficial factor for medication adherence. Marginalized groups describe issues such as language and cultural barriers while non-marginalized groups focus on systemic barriers to building a positive relationship, such as long wait times for short appointments.

Patients consider providers the major and most reliable source of information about their condition and their treatment [19, 38, 39, 43, 48, 49, 52–54, 57–59, 64, 66, 70, 76, 78, 93, 94, 96–98, 102, 104]. However, communication barriers may inhibit collaborative relationships, preventing a shared understanding of treatment and therefore hindering medication adherence [17, 20, 40, 42, 43, 48, 50, 52, 53, 55, 60, 64, 65, 68, 70, 72, 73, 76, 78, 81, 91, 94, 97, 99, 105–108]. Authors describe the barriers to communication between patients and providers as reflecting differences in underlying health beliefs and different desires and understandings of the model of care [17, 20, 40, 42, 43, 48, 50, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 60, 64, 65, 68, 70, 76, 81, 91, 93, 96, 98, 99, 101, 105–107]. Patients attribute communication barriers to the way clinicians communicate with them, including providing information that is ambiguous, incomplete, or irrelevant, provider time constraints, and lack of shared decision-making strategies among multiple health care providers [17, 20, 40, 42, 43, 48, 50, 52, 53, 55, 60, 64, 65, 68, 70, 72, 73, 76, 78, 81, 91, 94, 97, 99, 105–108]. Information inconsistency [17, 50, 68, 70, 81, 97, 105] and lack of clear information may result in misunderstandings, and lead patients to use other sources of information [22, 42, 43, 48, 50, 53, 55, 56, 68, 70, 73, 76, 91, 98, 99, 105–108]. Patients find nurses or pharmacists more accessible for information or to answer questions about medication [17, 19, 43, 51, 98, 105]. As briefly mentioned earlier, patients’ language and cultural barriers, as well as their low health literacy levels inhibit communication between patient and provider [20, 42, 43, 50, 55, 56, 59, 64, 70, 72, 78, 93].

Providers, while acknowledging the contributions of a collaborative model of care, address systemic, structural, cultural, and linguistic barriers to patient-provider relationships that impact medication adherence [17, 66, 75, 82–85, 95, 98, 110–112]. In particular, providers recognize different ways in which they may affect patient adherence, including poor “detective work” when devising treatment regimens, poor negotiation abilities, delay in starting insulin therapy, cultural insensitivity, incorrect a priori assumptions about patient knowledge and understanding of the treatment, as well as feelings of powerlessness and frustration which affects the healthcare professionals’ ability to provide adequate recommendations [17, 75, 84, 85, 112].

Health care providers also identify patient- related factors affecting their relationship, such as: patients’ passive role, communication barriers, cultural barriers, patients’ distrust in the provider, intentional non-compliance, and patients’ low health literacy levels [20, 83, 84, 95, 110, 112]. Providers describe patients’ passive behaviour as stemming from patients’ negative past clinical encounters, distrust in healthcare providers, deferential attitudes, or patients’ misinformed expectations [20, 83–85, 112]. Most importantly, clinicians value addressing patients’ needs, in order to “figure out” and”fix” reasons for non-compliance [66, 75, 82, 84, 85, 95].

Sometimes providers address the negative impact of structural and language barriers to patient-provider communication – which in turn hinders medication adherence [17, 20, 85, 95, 110]. Systemic problems include long waiting lists, busy schedules, and practice organization barriers, which limit physicians’ available time to communicate with patients [20, 95, 110]. In particular, time constraints and systemic barriers delay their decision to start treatment therapies (e.g. insulin), which need several clinical encounters to adequately instruct patients [84, 95, 110].

Information & knowledge

Patient accounts of how they negotiate their medication regimens offer explanations for why they choose to manage their condition in a way that suits their personal circumstances and understanding of their health, body, and diabetes [60, 68, 73, 79, 81, 102, 108]. Overall, studies present contradictory findings about the relationship between understanding and adherence [38, 44, 46, 57, 63, 65, 66, 70, 81, 94, 103, 107, 113]. For some patients, a lack of understanding and inadequate knowledge about the medication [47] and prevention of a complication [50, 52, 59] results in poorly controlled blood glucose levels and poor adherence [43, 50, 52, 56, 69, 71, 82, 91, 101]. In other instances, patients report that they understood medications’ importance, but not how the medications work [17, 40, 44, 53, 59, 78, 85, 91, 97, 103]. Thus, patients often report abstaining from medication when asymptomatic, or they consciously decide to take medication according to how they feel [17, 62, 69, 76]. Other studies describe patients as knowledgeable, but unable to translate this knowledge into appropriate action (e.g. “what to do when things go wrong”) [40, 91, 103, 108, 114]. This kind of understanding may improve with experience [44, 51, 94, 97], necessitating a set of problem solving strategies [51, 102, 115], including creative solutions to diabetes self-management [68, 94, 97, 100, 102]. In light of these contradictory findings we may conclude that the role of information and understanding varies in importance depending on individual circumstances.

Patients value the information received by their providers on medication treatment, self-management strategies and on navigating the health care system [19, 38, 43, 48, 52, 57, 70, 78]. Patients also value the information provided by a variety of ancillary resources, such as clinic dieticians and nutritionists and peer support groups [22, 47, 49, 55, 57] and educational programs, including self-management education classes and medication counselling services [19, 38, 48, 55, 65, 68, 70, 92, 97]. Additionally, patients note that they appreciate the opportunity to share information and knowledge, and learn from others who live with the same condition who successfully cope with their condition [22, 45–50, 52, 53, 55, 58, 68, 76, 88, 91]. However, patients also identify the need or desire for more information and management strategies [19, 38, 47–49, 53, 55, 66, 105, 108], especially in language and culture-specific ways [88, 91, 107, 116].

Providers describe patients’ lack of sufficient knowledge about the disease as one of the primary reasons underlying poor medication adherence [17, 84, 110]. As this provider reports, ‘Oh, I probably said that it [the cholesterol] was alright and then she thought is was alright to stop, something like that, that's possible? That happens: they think everything is in order again’ [95].

Providers also report a strong empathy for patients around ideas such as the complexity and impact of diabetes as an unpredictable, frustrating, and long-term disease, identifying the importance of involving and integrating all aspects of the patients’ life [75, 83]. Providers identify the following information priorities for patients: integrated knowledge acquisition about the nature of the disease, medications used and how they work, lifestyle factors (diet, nutrition, exercise), self-care, monitoring procedures, underlying processes of diabetes, and the relationship between diabetes symptoms, medication, and long term consequences [19, 20, 75, 82]. Providers consider discussions about medication-related issues, and improvement of patients’ medication knowledge, important to promoting medication adherence [66, 75, 82, 84, 85, 95]. Providers also recognize language barriers, which limit a more in-depth conversation about a patient's circumstances and health beliefs [20, 110].

Medication administration

For many patients, the administration of medication poses a significant barrier to adherence. Patients describe fear as a common barrier to insulin administration, in particular fear of needles, fear of consequences of administering insulin incorrectly, and the pain of injection or blood testing [37, 38, 41, 44, 46, 49, 50, 58, 69, 71, 73, 83, 88, 113, 117]. Other patients specifically mention they were not afraid of needles and did not find insulin injection painful [58]. Patients relate insulin administration to other psychological barriers, such as a feeling of stigma around the possession and use of an injectable medication because of the possibility of being mistaken for an illicit drug [37, 38, 41, 50, 58, 68, 73, 88, 100, 102].

According to several studies, co-morbid conditions represent a general barrier to medication administration [17, 22, 50, 57, 58, 66, 68, 77–80]. Patients who take multiple medications may experience forgetfulness, confusion about the purpose, name, and the potential for interactions with other medications [43, 44, 50, 59, 62, 64, 78–80, 99, 105, 117]. The burden of the medication regimen is typically linked to the rigidity of medication which impedes flexibility in every day life, as this patient reports, ‘just the timing and remembering to take your pills on time. It’s a real effort to take them at the right time” [37, 50, 58, 61, 68, 73, 88, 102, 106, 108]. The development of habit-forming routines may encourage medication adherence [59, 108]. When the patient hasn’t established, or has disrupted, the routine, medication adherence declines. This includes minor (e.g. skipping meals) [17, 59, 68, 76, 78, 79, 91, 118], or social and contextual factors in the patient’s life, such as childcare, domestic duties, or work schedules can interfere with patient’s routines [50, 61, 68, 94, 103].

Patients acknowledge family’s instrumental support as a practical means to help integrate the treatment regimen in patients’ daily lives [17, 49–52, 54, 56–59, 66, 68–70, 76, 78, 118]. However, some patients describe fear of being a burden on their family [49, 69, 77] or unsupportive family members as a direct barrier to medication adherence [17, 22, 37, 40, 48, 49, 52, 66, 68, 69, 77, 79, 118].

In general, providers do not recognize the administration of medication as a potential barrier to adherence, except in the case of patients with physical or cognitive impairments [75,82,84], co-morbid conditions [75, 83, 84], or related to treatments, for example fear of needles upon initiation of insulin treatment [20, 82, 84, 86, 110]. Healthcare providers perceive family support as crucial for patients with poor cognitive and physical resources,[82, 110] for reinforcing providers’ medication instructions, and for holding the patient accountable for his/her self-management [17, 82, 84, 110].

Social and cultural health beliefs

Health beliefs about medication and diabetes are often linked to social or cultural understandings about the body, diabetes and medication, which in turn can affect medication adherence in many different ways. Multiple factors shape these health beliefs, such as the information sources used by the patient, past experiences, attitudes of others, faith and religious beliefs, education, and cultural community [38, 41, 44, 48, 71]. A patient's health belief system may affect the way he or she decides to approach medication adherence, and how to integrate (or not) the requirements of the medication regimen into everyday life [44, 76].

A patient's health beliefs and cultural background will also affect the relationship s/he desires with the prescribing physician [44, 48, 50, 59, 60, 62, 69, 71, 72, 74, 89, 91, 117]. For instance, patients who are members of historically oppressed communities by the dominant culture can be suspicious of medical advice [69, 71, 74, 89, 117]. Patients from cultures that perceive physicians as high status individuals with significant authority may feel uncomfortable asking questions [20, 93, 98]. Several papers recommend including the patient in a culturally appropriate way as an active partner of care to improve medication adherence [39, 41, 57, 58, 70, 93]. However, providers should adapt to the patients’ beliefs and preferences, as some patients may refuse to work with clinicians in this way.

Social and cultural beliefs also affect patient preferences for allopathic (Western biomedicine) compared to traditional medications. Some patients express their intention to take them alongside traditional medications [53, 56, 62, 74, 89]. Many patients indicate a preference for traditional or herbal medications, and a suspicion or distrust of allopathic medication [20, 44, 53, 62, 69, 79, 83, 88, 89, 92, 94, 116, 117]. These patients describe allopathic medicine as unnatural [38, 44, 78, 79, 88, 92], the cause of side effects and complications [20, 53, 62, 78, 88, 92, 117], incongruent with their understanding of holistic health [20, 79, 88, 94]. In contrast, patients describe traditional remedies as effective [88, 89, 92, 116], a link to their past and present cultural communities [71, 88] and easier to access [20, 88, 89].

Provider perspectives rarely address the issue of traditional medication alongside or instead of allopathic medication [95]. Providers are more likely to mention challenges linked with the patient's cultural background and beliefs, such as aversion to insulin, fatalistic attitudes, the perception that fat is healthier or a desire to please the physician [20, 83, 84, 110, 112].

Financial issues

Patients widely mention the cost of medication as a barrier to medication adherence [17–19, 37, 42, 44, 46, 50, 64, 68, 70, 75, 76, 81, 89, 91–93, 97, 119], although studies involving participants with access to public health insurance less likely to mention cost as a barrier [47, 73]. Financial barriers can extend beyond the cost of medication and physician services. Even patients with health insurance can struggle to afford testing supplies, syringes, and non-physician supportive care [17, 19, 37, 70, 75, 76, 81, 91, 92, 97]. Patients living in poverty also face other structural and material constraints such as low health literacy, poor quality housing, shift work, stress, inability to access healthy food etc., that affect their ability to adhere to medication regimens [37, 68, 70, 89, 119]. When faced with financial constraints, patients may use tactics including: taking medication less often than recommended, choosing the most “important” medication to pay for, sharing pills with other people, drawing on personal capabilities and social networks, and asking their doctor for help [18, 50, 68, 89, 92].

Providers interviewed in some projects understand the financial barriers that patients may face, but commonly do not identify this issue as a barrier to medication adherence [17, 18, 75, 83, 112]. In some cases, while providers may recognize that some patients struggle with the cost of medication, ‘these were clearly secondary concerns from the clinicians' perspective’ [18]. In several instances, clinicians acknowledge the cost of medication as a contextual barrier along with other struggles related to low socio-economic status [83, 112]. While some clinicians perceive that these struggles are outside of their realm of influence [75], others offer creative strategies for alleviating financial burden such as prescribing generics, giving samples, changing the regimen to accommodate constraints or helping patients participate in patient assistance programs [18, 75].

Discussion

Extensive qualitative research exists on the topic of barriers to medication adherence amongst community-dwelling adults with Type 2 diabetes. Our synthesis of this research to date suggests that providers and patients share some common understandings of these barriers, as well as facilitators to overcome them. However, the qualitative research also identifies many points of misunderstanding, miscommunication, and missed opportunities for intervention. In general, providers tend to limit their focus to clinically-oriented issues, while patients describe a much wider range of problems with medication adherence that arise from the personal, social, and practical challenges of living with diabetes. To the extent providers understand and address these wider concerns (possibly through a multidisciplinary professional, patient-centered approach to care), they will potentially improve both medication adherence and patient experiences. This reflects what the literature addresses as patient-models of care, where patients adhere to medications and not comply (emphasis added) overtaking past paternalistic models of care [6, 16, 120].

Our synthesis on medication adherence may contribute to define more clearly the key dimensions of the person-centered (PC) model of care and illustrate how this model may improve medication adherence among Type 2 diabetic patients. According to Bower and Mead [16], PC care is based on the following dimensions: inclusion of biopsychosocial factors, viewing the patient as a person, enhancing patient’s empowerment and autonomy, involving the patient in the decision-making process through a two-way communication process and negotiation, encouraging a collaborative and mutual trusting relationship between patient and provider, and emphasizing the doctor as a person.

Our study shows that patients and providers often agree on the importance of medication adherence for symptom improvement, the benefit of a collaborative and responsive relationship between patient and provider, and effective communication of information. The integration of patient’s perspectives in the clinical relationship, based on a mutual and trusting relationship, broadens the scope of the explanatory model of illness by addressing different ‘dysfunctional’ states and the possible interventions areas to improve adherence [7, 10, 16, 120–122]. As the PC model of care describes, these factors help patients integrate their medication regimen into their own system of health beliefs, the individual context of their everyday lives, and their changing circumstances [10, 16, 120, 121, 123, 124].

Conversely, patients commonly cite providers’ lack of collaboration, lack of interest in the patient’s life and context, poor communication, or time constraints as interfering with their medication adherence. Providers on the other hand, as documented in recent studies [125–127], tend to address systemic barriers, such as limited time consultations and lack of inter-professional collaboration, as obstacles challenging the prioritization of patients’ medical and psychosocial needs.

Providers and patients differ significantly on how best to influence patients’ self-management practices. Providers tend to focus on patients’ knowledge about the physiology of the disease and role of medical and lifestyle interventions: i.e., the nature of the problem, what needs to be done, and how. While some providers do recognize the importance of emotions and psychosocial factors, providers relate these more to the motivation, than to the capacity, to use medication properly. Recent studies corroborate these findings, indicating that providers consider motivation as crucial for patients’ understanding of the illness and effective medical education [126, 128].

Patients, however, describe diabetes and medication self-management as a multi-dimensional experience. Practical aspects include finances, daily routines, and the need for instrumental support. Psychosocial aspects include health beliefs, emotional impacts, social and cultural understandings of diabetes and medications. Self-management models based on behaviour and integration theories reflect this perspective on medication adherence behaviours and self-care activities, acknowledging both the psychosocial and biomedical nature of the medication regimen [129, 130] and highlighting that perceptions may differ between patients and providers on treatments goals and strategies [131]. Providers’ focus on biomedical problem-solving can also leave patients feeling “reduced to their disease”. This runs counter to the person- or patient-centered care approach that calls for treating people holistically, with their attention to their disease placed in context of attention to other factors in their lives [16, 121, 123]. All of these factors influence the way that patients interpret and apply medical advice.

This synthesis of the qualitative research on patient and provider perspectives underscores the recommended shift from the traditional medical view of medication “compliance” to the more patient-centered view of medication “concordance” with patients’ many other needs, pressures and demands [7, 10, 13, 16, 121, 123].

Strengths and the limitations

A number of strengths and limitations of this study are worth noting. First, this study provides an updated and comprehensive qualitative systematic synthesis of Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ different perspectives on medication adherence. Existing systematic reviews of qualitative research focus on diabetes management more broadly [122, 132–134], and quantitative reviews on medication adherence elicit different types of information. For example, quantitative studies concentrate on measuring medication adherence rates among Type 2 diabetes patients, or measuring medication adherence rates for specific drug therapies, nutrition regimens and educational interventions designed to improve adherence, rather than addressing the reasons and experiences of trying to adhere to medication regimes [12, 135–139]. By comparing patient and provider perspectives on this issue, we are able to provide an interpretive synthesis of the constellation of challenges that patients may face when prescribed a medication regime for their diabetes.

Another strength of this study is the large body of qualitative research available for synthesis on this topic: we were able to include 86 studies that together captured thousands of patients’ experiences. The integrative meta-synthesis method also allowed us to distil robust thematic findings, each supported by a number of studies and therefore more transferable across settings. The rigor of the synthesis allows establishing generalizability and consistency of the findings among a large number of studies and across different countries, patient population groups, and patient demographic differences. A significant portion of the included articles (33 out of 86) focused on very specific populations of diabetic patients, such as indigenous groups, immigrants, and minorities. We used a constant comparative technique to examine medication adherence barriers across such groups in our analysis and found our main categories to be consistent across groups, with some variation in the sub-categories. For example, we noted the consistency of the theme of the importance of the patient-provider relationship across studies that included marginalized and non-marginalized populations. Comparative analysis of this theme revealed that the patient-physician relationship was consistently mentioned as important by authors of both types of studies, although they tended to focus on different aspects of this relationship. For example, marginalized participants spoke about the difficulty in communicating with language and cultural barriers and the impediments that this provided to a strong, supportive relationship with their physician. Non-marginalized participants were more likely to focus on barriers such as wait times and short length of appointments. Both groups emphasized the importance of this relationship on their ability to self-manage their diabetes. Similarly, the results did not present consistent differences by age or gender across study populations, as the populations were overall consistent in terms of age and gender. We found that barriers to medication adherence were consistent across the different diabetic and demographic populations considered in the 86 studies. Therefore we are not presenting the results as stratified along these lines. Findings concerning culture in particular may be less transferable to jurisdictions and cultures not captured in this body of research. A limitation of this study is its focus on English-language research reports.

This study was limited also in other ways. First, this review includes only research conducted between 2002–2013. These dates reflect an attempt to include a manageable body of current literature. Given the depth and complexity of qualitative data, 86 studies provide a large body of data to describe and interpret. The WHO report on medication adherence published in 2003 [1] offers an authoritative summary of the state of knowledge before 2002; we have provided a review of this foundational literature in the introduction of the current manuscript.

Second, this meta-synthesis retrieved a great number of patient experiences reflecting a limitation of the underlying body of research: the relatively fewer qualitative research into providers’ perspective on patient-barriers to medication adherence among Type 2 diabetes patients. Recent studies corroborate our results reinforcing the sense of saturation of our data [125–128, 131], however, because studies on patient, not provider, perspectives continue to dominate the field, we highlight providers as an important population for future qualitative investigation and possibly multi-methodology research syntheses.

Conclusion

This study synthesized Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ views about medication adherence, highlighting that these groups have different medication adherence priorities. While providers tend to focus on patients’ motivations and medication administration practices, patient accounts emphasize their experience of diabetes as part of a holistic consideration of their whole lives. Providers shared clinically oriented perspectives, detailing rich and sophisticated conditional reasoning about their efforts to persuade patients to adhere to their medication regimen. Patients’ accounts of medication adherence describe individual experiences of diabetes medication that are deeply embedded within the context of the individual’s particular life circumstances, emphasizing that medication self-management practices are built upon more than just knowledge and motivation for change. The conceptual divide between patients and providers on the topic medication adherence enriches our understanding of why medication adherence may be experienced as an intractable issue by both patients and providers. The findings of this synthesis may assist providers in identifying potential factors that affect a particular patient’s medication practices. Taking a patient-centered approach to medication self-management may encourage increased understanding the priorities and experiences patients, encouraging providers to identify the multiple underlying factors that promote or inhibit medication adherence in their patients creating the opportunity for patients to voice their questions or concerns about their medication regimens. Interventions that aim to improve medication adherence will benefit from considering the issue of adherence from a patient-centered model of care by tailoring the medication regimen to patients’ life contexts, preferences and self-management practices.

References

Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action: World Health Organization 2003

Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Padwal RS, Tsuyuki RT, Varney J, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ. 2006;333(7557):15. doi:10.1136/bmj.38875.675486.55.

Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization2011

IDF Diabetes Atlas. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2013.

Canada PHAo. Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa2011

Cushing A, Metcalfe R. Optimizing medicines management: From compliance to concordance. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(6):1047–58.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Britten N. “Doing prescribing”: how might clinicians work differently for better, safer care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12 Suppl 1:i33–6.

Haynes RB, McKibbon KA, Kanani R. Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet. 1996;348(9024):383–6.

van Dulmen S, Sluijs E, van Dijk L, de Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J. Patient adherence to medical treatment: a review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):55.

Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(5):331–42.

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x.

DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42(3):200–9.

Marinker M, Shaw J. Not to be taken as directed. BMJ. 2003;326(7385):348–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7385.348.

Delamater AM. Improving Patient Adherence. Clinical Diabetes. 2006;24(2):71–7. doi:10.2337/diaclin.24.2.71.

Marinker M. Personal paper: writing prescriptions is easy. BMJ. 1997;314(7082):747. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7082.747.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2000;51(7):1087–110.

Williams AF, Manias E, Walker R. Adherence to multiple, prescribed medications in diabetic kidney disease: A qualitative study of consumers’ and health professionals’ perspectives. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(12):1742–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.07.002.

Hunt LM, Kreiner M, Brody H. The changing face of chronic illness management in primary care: a qualitative study of underlying influences and unintended outcomes. Ann Fam Mede. 2012;10(5):452–60.

Garrett DG, Martin LA. The Asheville Project: participants’ perceptions of factors contributing to the success of a patient self-management diabetes program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):185–90.

Renfrew MR, Taing E, Cohen MJ, Betancourt JR, Pasinski R, Green AR. Barriers to Care for Cambodian Patients with Diabetes: Results from a Qualitative Study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2):633–55.

Vanstone M, Brundisini F, Hulan D, DeJean D, Giacomini M. Patient Experiences of Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Toronto, ON.2014

Shaw RL, Booth A, Sutton AJ, Miller T, Smith JA, Young B, et al. Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4(1):5.

Wilczynski NL, Marks S, Haynes RB. Search strategies for identifying qualitative studies in CINAHL. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(5):705–10.

Wong S, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Medinfo. 2004;11(pt 1):311–6.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Creating metasummaries of qualitative findings. Nursing Res. 2003;52(4):226–33.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(2):153–70. doi:10.1002/nur.10072.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York, NY: Springer Pub. Co.; 2006.

Saini M, Shlonsky A. Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. Pocket Guides to Social Research Methods. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Melia KM. Recognizing quality in qualitative research. In: Bourgeault IL, DeVries R, Dingwall R, editors. SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Health Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2010. p. 559–74.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):59.

Finfgeld-Connett D. Meta-synthesis of presence in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55(6):708–14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03961.x.

Noblit G, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1988.

Paterson B. Coming out as ill: understanding self-disclosure in chronic illness from a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Reviewing Research Evidence for Nursing Practice. 2007:73–83

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(3):213–9.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory : a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006.

Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research : techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Inc.; 2008.

Hu J, Amirehsani KA, Wallace DC, Letvak S. The Meaning of Insulin to Hispanic Immigrants With Type 2 Diabetes and Their Families. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(2):263–70. doi:10.1177/0145721712437559.

Noakes H. Perceptions of black African and African-Caribbean people regarding insulin. J Diab Nurs. 2010;14(4):148.

Parry O, Peel E, Douglas M, Lawton J. Issues of cause and control in patient accounts of Type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(1):97–107.

Wong M, Haswell-Elkins M, Tamwoy E, McDermott R, D’Abbs P. Perspectives on clinic attendance, medication and foot-care among people with diabetes in the Torres Strait Islands and Northern Peninsula Area. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(3):172–7.

Morris JE, Povey RC, Street CG. Experiences of people with type 2 diabetes who have changed from oral medication to self-administered insulin injections: a qualitative study. Practical Diabetes International. 2005;22(7):239–43.

Wan CR, Vo L, Barnes CS. Conceptualizations of patient empowerment among individuals seeking treatment for diabetes mellitus in an urban, public-sector clinic. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):402–4. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.09.010.

Lee DY, Armour C, Krass I. The development and evaluation of written medicines information for type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(6):918–30.

Nair KM, Levine MA, Lohfeld LH, Gerstein HC. “I take what I think works for me”: a qualitative study to explore patient perception of diabetes treatment benefits and risks. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;14(2):e251–9.

Adili F, Higgins I, Koch T. Inside the PAR group: The group dynamics of women learning to live with diabetes. Action Res. 2012;10(4):373–86. doi:10.1177/1476750312456710.

Cardol M, Rijken M, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk H. People with mild to moderate intellectual disability talking about their diabetes and how they manage. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2012;56(4):351–60.

Gazmararian JA, Ziemer DC, Barnes C. Perception of Barriers to Self-care Management Among Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(5):778–88. doi:10.1177/0145721709338527.

Goering EM, Matthias MS. Coping with chronic illness: information use and treatment adherence among people with diabetes. Commun Medicine. 2010;7(2):107–18.

Mathew R, Gucciardi E, De Melo M, Barata P. Self-management experiences among men and women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:122.

Mishra SI, Gioia D, Childress S, Barnet B, Webster RL. Adherence to Medication Regimens among Low-Income Patients with Multiple Comorbid Chronic Conditions. Health Soc Work. 2011;36(4):249–58.

Moser A, van der Bruggen H, Widdershoven G, Spreeuwenberg C. Self-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative investigation from the perspective of participants in a nurse-led, shared-care programme in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:91.

Vinter-Repalust N, Petricek G, Katic M. Obstacles which patients with type 2 diabetes meet while adhering to the therapeutic regimen in everyday life: qualitative study. Croat Med J. 2004;45(5):630–6.

Barton SS, Anderson N, Thommasen HV. The diabetes experiences of Aboriginal people living in a rural Canadian community. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(4):242–6.

Felea MG, Covrig M, Manea DI, Titan E. Perceptions of Life Burdens and of the Positive Side of Life in a Group of Elderly Patients with Diabetes: A Qualitative Analysis through Grounded Theory. Rev Cercet Interv Soc. 2013;40:7–20.

Heisler M, Spencer M, Forman J, Robinson C, Shultz C, Palmisano G, et al. Participants’ Assessments of the Effects of a Community Health Worker Intervention on Their Diabetes Self-Management and Interactions with Healthcare Providers. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S270–S9. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.016.

Helsel D, Mochel M, Bauer R. Chronic illness and Hmong shamans. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;16(2):150–4.

Morrow AS, Haidet P, Skinner J, Naik AD. Integrating diabetes self-management with the health goals of older adults: a qualitative exploration. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(3):418–23.

Bogatean MP, H√¢ncu N. People with type 2 diabetes facing the reality of starting insulin therapy: factors involved in psychological insulin resistance. Pract Diabetes Int. 2004;21(7):247–52.

Borgsteede SD, Westerman MJ, Kok IL, Meeuse JC, de Vries T, Hugtenburg JG. Factors related to high and low levels of drug adherence according to patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Phar. 2011;33(5):779–87. doi:10.1007/s11096-011-9534-x.

George SR, Thomas SP. Lived experience of diabetes among older, rural people. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(5):1092–100.

Hornsten A, Jutterstrom L, Audulv A, Lundman B. A model of integration of illness and self-management in type 2 diabetes. J Nurs Healthcare Chronic Illnesses. 2011;3(1):41–51. doi:10.1111/j.1752-9824.2010.01078.x.

Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hallowell N, Hanna L, Douglas M. Perceptions and experiences of taking oral hypoglycaemic agents among people of Pakistani and Indian origin: qualitative study. BMJ. 2005;330(7502):28.

Rise MB, Pellerud A, Rygg LO, Steinsbekk A. Making and Maintaining Lifestyle Changes after Participating in Group Based Type 2 Diabetes Self-Management Educations: A Qualitative Study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064009.

Tjia J, Givens JL, Karlawish JH, Okoli-Umeweni A, Barg FK. Beneath the surface: discovering the unvoiced concerns of older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(1):40–52.

Shaw JL, Brown J, Khan B, Mau MK, Dillard D. Resources, roadblocks and turning points: a qualitative study of American Indian/Alaska Native adults with type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):86–94.

Burke JA, Earley M, Dixon LD, Wilke A, Puczynski S. Patients with diabetes speak: Exploring the implications of patients’ perspectives for their diabetes appointments. Health Commun. 2006;19(2):103–14. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1902_2.

Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):306–11. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53119.x.

Hinder S, Greenhalgh T. “This does my head in”. Ethnographic study of self-management by people with diabetes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:83.

Bhattacharya G. Psychosocial Impacts of Type 2 Diabetes Self-Management in a Rural African-American Population. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(6):1071–81. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9585-7.

Nagelkerk J, Reick K, Meengs L. Perceived barriers and effective strategies to diabetes self-management. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(2):151–8.

Brown K, Avis M, Hubbard M. Health beliefs of African-Caribbean people with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(539):461–9.

Grant RW, Pabon-Nau L, Ross KM, Youatt EJ, Pandiscio JC, Park ER. Diabetes oral medication initiation and intensification: patient views compared with current treatment guidelines. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(1):78–84.

Hayes RP, Bowman L, Monahan PO, Marrero DG, McHorney CA. Understanding diabetes medications from the perspective of patients with type 2 diabetes: prerequisite to medication concordance. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32(3):404–14.

Henderson LC. Divergent models of diabetes among American Indian elders. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2010;25(4):303–16.

Lutfey K. On practices of ‘good doctoring’: reconsidering the relationship between provider roles and patient adherence. Sociol Health Illn. 2005;27(4):421–47.

Rahim-Williams B. Beliefs, behaviors, and modifications of type 2 diabetes self-management among African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(3):203–15.

Feil DG, Lukman R, Simon B, Walston A, Vickrey B. Impact of dementia on caring for patients’ diabetes. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(7):894–903. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.569485.

Lawton J, Peel E, Parry O, Douglas M. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of taking oral glucose-lowering agents: a longitudinal qualitative study. Diabetic Med. 2008;25(4):491–5. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02400.x.

Mc Sharry J, Bishop FL, Moss-Morris R, Kendrick T. ‘The chicken and egg thing’: cognitive representations and self-management of multimorbidity in people with diabetes and depression. Psychol Health. 2013;28(1):103–19.

Stack RJ, Elliott RA, Noyce PR, Bundy C. A qualitative exploration of multiple medicines beliefs in co-morbid diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetic Med. 2008;25(10):1204–10.

Corser W, Lein C, Holmes-Rovner M, Gossain V. Contemporary Adult Diabetes Mellitus Management Perceptions. Patient. 2010;3(2):101–11. doi:10.2165/11318450-000000000-00000.

Agarwal G, Nair K, Cosby J, Dolovich L, Levine M, Kaczorowski J, et al. GPs’ approach to insulin prescribing in older patients: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(553):569–75.

Brown JB, Harris SB, Webster-Bogaert S, Wetmore S, Faulds C, Stewart M. The role of patient, physician and systemic factors in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):344–9.

Jeavons D, Hungin AP, Cornford CS. Patients with poorly controlled diabetes in primary care: healthcare clinicians’ beliefs and attitudes. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(967):347–50.

Wens J, Vermeire E, Royen PV, Sabbe B, Denekens J. GPs’ perspectives of type 2 diabetes patients’ adherence to treatment: A qualitative analysis of barriers and solutions. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):12.

Phillips A. Starting patients on insulin therapy: diabetes nurse specialist views. Nurs Stand. 2007;21(30):35–40.

Connor U, Anton M, Goering E, Lauten K, Hayat A, Roach P, et al. Listening to patients’ voices: linguistic indicators related to diabetes self-management. Commun Med. 2012;9(1):1–12.

Ho EY, James J. Cultural barriers to initiating insulin therapy in Chinese people with type 2 diabetes living in Canada. Can J Diab. 2006;30(4):390–6.

Lynch EB, Fernandez A, Lighthouse N, Mendenhall E, Jacobs E. Concepts of diabetes self-management in Mexican American and African American low-income patients with diabetes. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(5):814–24.

Broom D, Whittaker A. Controlling diabetes, controlling diabetics: moral language in the management of diabetes type 2. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2371–82. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.002.

Mohan AV, Riley MB, Boyington DR, Kripalani S. Illustrated medication instructions as a strategy to improve medication management among Latinos: a qualitative analysis. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(2):187–97.

Barko R, Corbett CF, Allen CB, Shultz JA. Perceptions of diabetes symptoms and self-management strategies: a cross-cultural comparison. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22(3):274–81.

Bissell P, May CR, Noyce PR. From compliance to concordance: barriers to accomplishing a re-framed model of health care interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(4):851–62. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00259-4.

Wang Y, Chuang L, Bateman WB. Focus group study assessing self-management skills of Chinese Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(5):869–74.

Ab E, Denig P, van Vliet T, Dekker JH. Reasons of general practitioners for not prescribing lipid-lowering medication to patients with diabetes: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:24.

Venkatesh S, Weatherspoon L. Social and health care provider support in diabetes self-management. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(1):112–21.

Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Ratsep A, Levasseur G, Petek D, van Dam H, et al. Obstacles to adherence in living with type-2 diabetes: an international qualitative study using meta-ethnography (EUROBSTACLE). Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1(1):25–33.

Courtenay M, Stenner K, Carey N. The views of patients with diabetes about nurse prescribing. Diabetic Med. 2010;27(9):1049–54.

Onwudiwe NC, Mullins CD, Winston RA, Shaya FT, Pradel FG, Laird A, et al. Barriers to self-management of diabetes: a qualitative study among low-income minority diabetics. Ethnicity & Disease. 2011;21(1):27–32.

Jenkins N, Hallowell N, Farmer AJ, Holman RR, Lawton J. Participants’ experiences of intensifying insulin therapy during the Treating to Target in Type 2 Diabetes (4-T) trial: qualitative interview study. Diabetic Med. 2011;28(5):543–8.

Klein HA, Meininger AR. Self management of medication and diabetes: Cognitive control. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Paart A-Syst Hum. 2004;34(6):718–25. doi:10.1109/tsmca.2004.836791.

Rayman K, Ellison G. Home alone: the experience of women with type 2 diabetes who are new to intensive control. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25(10):900–15.

Klein HA, Lippa KD. Assuming control after system failure: type II diabetes self-management. Cogn Technol Work. 2012;14(3):243–51. doi:10.1007/s10111-011-0206-3.

Wilson PM, Kataria N, McNeilly E. Patient and carer experience of obtaining regular prescribed medication for chronic disease in the English National Health Service: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:11. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-192.

Lamberts EJF, Bouvy ML, van Hulten RP. The role of the community pharmacist in fulfilling information needs of patients starting oral antidiabetics. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2010;6(4):354–64. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.10.002.

Gorawara-Bhat R, Huang ES, Chin MH. Communicating with older diabetes patients: Self-management and social comparison. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(3):411–7. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.011.

Guell C. Self-care at the margins: meals and meters in migrants’ diabetes tactics. Med Anthropol Q. 2012;26(4):518–33.

Frandsen KB, Kristensen JS. Diet and lifestyle in type 2 diabetes: the patient’s perspective. Pract Diab Int. 2002;19(3):77–80.

Borovoy A, Hine J. Managing the unmanageable: elderly Russian Jewish emigres and the biomedical culture of diabetes care. Med Anthropol Q. 2008;22(1):1–26.

Patel N, Stone MA, Chauhan A, Davies MJ, Khunti K. Insulin initiation and management in people with Type 2 diabetes in an ethnically diverse population: the healthcare provider perspective. Diabetic Med. 2012;29(10):1311–6.

Sibley A, Latter S, Richard C, Lussier MT, Roberge D, Skinner TC, et al. Medication discussion between nurse prescribers and people with diabetes: an analysis of content and participation using MEDICODE. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:2323–36.

Thorlby R, Jorgensen S, Ayanian JZ, Sequist TD. Clinicians’ views of an intervention to reduce racial disparities in diabetes outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(9–10):968–77.

Holmstrom IM, Rosenqvist U. Misunderstandings about illness and treatment among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(2):146–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03274.x.

Lippa KD, Klein HA. Portraits of patient cognition: how patients understand diabetes self-care. Can J Nurs Res. 2008;40(3):80–95.

Lippa KD, Klein HA, Shalin VL. Everyday expertise: cognitive demands in diabetes selfmanagement. Hum Factors. 2008;50(1):112–20.

Coronado GD, Thompson B, Tejeda S, Godina R. Attitudes and beliefs among Mexican Americans about type 2 diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(4):576–88.

Bhattacharya G. Self-management of type 2 diabetes among African Americans in the Arkansas Delta: a strengths perspective in social-cultural context. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):161–78.

Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Family support, medication adherence, and glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1239–45.

Raphael D, Daiski I, Pilkington B, Bryant T, Dinca-Panaitescu M, Dinca-Panaitescu S. A toxic combination of poor social policies and programmes, unfair economic arrangements and bad politics: the experiences of poor Canadians with Type 2 diabetes. Critical Public Health. 2012;22(2):127–45. doi:10.1080/09581596.2011.607797.

Bezreh T, Laws MB, Taubin T, Rifkin DE, Wilson IB. Challenges to physician–patient communication about medication use: a window into the skeptical patient’s world. Patient preference and adherence. 2012;6:11–8. doi:10.2147/PPA.S25971.

Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An Integrative Model of Patient-Centeredness – A Systematic Review and Concept Analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107828. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107828.

Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Ratsep A, Levasseur G, Petek D, van Dam H, et al. Obstacles to adherence in living with type-2 diabetes: an international qualitative study using meta-ethnography (EUROBSTACLE). Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1(1):25–33. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2006.07.002.

Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in Patient–Physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516–28. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. Copyright 2001 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Sondergaard E, Willadsen TG, Guassora AD, Vestergaard M, Tomasdottir MO, Borgquist L, et al. Problems and challenges in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity: General practitioners’ views and attitudes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(2):121–6. doi:10.3109/02813432.2015.1041828.

Krall J, Gabbay R, Zickmund S, Hamm ME, Williams KR, Siminerio L. Current perspectives on psychological insulin resistance: primary care provider and patient views. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(4):268–74. doi:10.1089/dia.2014.0268.

Ritholz MD, Beverly EA, Brooks KM, Abrahamson MJ, Weinger K. Barriers and facilitators to self-care communication during medical appointments in the United States for adults with type 2 diabetes. Chronic illness. 2014;10(4):303–13. doi:10.1177/1742395314525647.

Jones L, Crabb S, Turnbull D, Oxlad M. Barriers and facilitators to effective type 2 diabetes management in a rural context: a qualitative study with diabetic patients and health professionals. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(3):441–53. doi:10.1177/1359105312473786.

Nagelkerk J, Reick K, Meengs L. Perceived barriers and effective strategies to diabetes self-management. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(2):151–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03799.x.

Funnell MM, Tang TS, Anderson RM. From DSME to DSMS: Developing Empowerment-Based Diabetes Self-Management Support. Diabetes Spectrum. 2007;20(4):221–6. doi:10.2337/diaspect.20.4.221.

Akohoue SA, Patel K, Adkerson LL, Rothman RL. Patients’, caregivers’, and providers’ perceived strategies for diabetes care. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(3):433–40. doi:10.5993/AJHB.39.3.15.

Gomersall T, Madill A, Summers LK. A metasynthesis of the self-management of type 2 diabetes. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(6):853–71. doi:10.1177/1049732311402096.

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2003;56(4):671–84.

Ho AYK, Berggren I, Dahlborg-Lyckhage E. Diabetes empowerment related to Pender’s Health Promotion Model: A meta-synthesis. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12(2):259–67. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00517.x.

Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1218–24.

Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Ceriello A, Giugliano D. Prevention and control of type 2 diabetes by Mediterranean diet: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89(2):97–102. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.019.

Hutchins V, Zhang B, Fleurence RL, Krishnarajah G, Graham J. A systematic review of adherence, treatment satisfaction and costs, in fixed-dose combination regimens in type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(6):1157–68. doi:10.1185/03007995.2011.570745.

Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1589–97. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16202-8.

Van Camp YP, Van Rompaey B, Elseviers MM. Nurse-led interventions to enhance adherence to chronic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4):761–70. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1419-y.

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by the Government of Ontario through a Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health System Research Fund grant entitled “Harnessing Evidence and Values for Health System Excellence”. We appreciate insights and direction on earlier related work provided by the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee’s Expert Advisory Panel on Community Care for Type 2 Diabetes. The views expressed in the manuscript are the views of the authors and should not are taken to represent the views of the Government of Ontario or anyone else acknowledged here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FB carried out the data extraction and analysis, and drafted the final manuscript. MV conceived, designed and coordinated the study, carried out the data extraction and analysis, helped to draft the manuscript, has revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and edited the final draft. DH carried out the data extraction and analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. DD designed the search strategy and undertook the searches, and helped to draft the manuscript. MG conceived the study, participated in its design, has revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and edited the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brundisini, F., Vanstone, M., Hulan, D. et al. Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ differing perspectives on medication nonadherence: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res 15, 516 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1174-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1174-8