Abstract

Background

Although chiropractors in the United States (US) have long suggested that their approach to managing spine pain is less costly than other health care providers (HCPs), it is unclear if available evidence supports this premise.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted using a comprehensive search strategy to uncover studies that compared health care costs for patients with any type of spine pain who received chiropractic care or care from other HCPs. Only studies conducted in the US and published in English between 1993 and 2015 were included. Health care costs were summarized for studies examining: 1. private health plans, 2. workers’ compensation (WC) plans, and 3. clinical outcomes. The quality of studies in the latter group was evaluated using a Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list.

Results

The search uncovered 1276 citations and 25 eligible studies, including 12 from private health plans, 6 from WC plans, and 7 that examined clinical outcomes. Chiropractic care was most commonly compared to care from a medical physician, with few details about the care received. Heterogeneity was noted among studies in patient selection, definition of spine pain, scope of costs compared, study duration, and methods to estimate costs. Overall, cost comparison studies from private health plans and WC plans reported that health care costs were lower with chiropractic care. In studies that also examined clinical outcomes, there were few differences in efficacy between groups, and health care costs were higher for those receiving chiropractic care. The effects of adjusting for differences in sociodemographic, clinical, or other factors between study groups were unclear.

Conclusions

Although cost comparison studies suggest that health care costs were generally lower among patients whose spine pain was managed with chiropractic care, the studies reviewed had many methodological limitations. Better research is needed to determine if these differences in health care costs were attributable to the type of HCP managing their care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spine pain is one of the most common and costly causes of health care utilization in the United States (US), with 61 % of patients seeking care from a medical physician (i.e. medical doctor (MD) or doctor of osteopathy (DO)), 28 % from a chiropractor, and 11 % from both a medical physician and a physical therapist (PT) [1–4]. Chiropractors in the US treat spine pain almost exclusively, with the most common indication for care being low back pain (LBP) (68 %), followed by neck pain (12 %), and mid-back pain (6 %) [5]. By contrast, only 3 % of office visits to medical physicians are related to spine pain [6].

Studies have reported that chiropractors have more confidence in their ability to manage spine pain than medical physicians, and that patients with spine pain report higher levels of satisfaction with chiropractic care than care from a medical physician [7–9]. Proponents of chiropractic maintain that it offers a more cost-effective approach to managing spine pain for a variety of reasons, including lower fees for office visits, use of x-rays rather than more advanced diagnostic imaging, lower referral rates to spine specialists or surgeons, and scope of practice limitations related to medications, injections, and surgery [10].

Previous reviews have examined the cost effectiveness of chiropractic care for occupational LBP, spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) for spine pain, treatments endorsed by clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for LBP, conservative care for neck pain, and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies for spine pain [11–17]. However, such reviews included a multitude of therapies and countries, and were therefore not focused on chiropractic care for spine pain in the US.

The primary objective of this study was to systematically review cost comparison studies examining chiropractic care for spine pain in the US.

Methods

Literature search

This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews [18]. A broad search combining indexed search terms and free text search terms related to chiropractic care (developed by the authors), spine pain (adapted from the Cochrane Back Review Group search strategy), and cost comparison studies (developed by the authors) was undertaken in August 2013 and an updated search was performed in August 2015 using the OvidSP interface for the Medline, Embase, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (EED), and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases. Additional searches were conducted in the CEA registry (https://research.tufts-nemc.org/cear4/), Index to Chiropractic Literature (ICL) (http://www.chiroindex.org/), and EconLit (American Economic Association) (https://www.aeaweb.org//econlit/efm/index.php) databases. References from previous related reviews and author files were also searched. The search strategy used in Medline is included in Additional file 1; others are available upon request [19, 20].

Inclusion criteria

Studies that met all of the following criteria were deemed eligible for this review:

-

1.

At least one study group received chiropractic care (i.e. care provided by a chiropractor, regardless of the interventions used, since these often vary or are not specified in study protocols);

-

2.

At least one study group did not receive chiropractic care, or study design otherwise allowed for comparison of chiropractic care to another approach (e.g. study comparing medical care to medical care and chiropractic care);

-

3.

Primary condition treated was spine pain (i.e. neck pain, mid-back pain, or LBP with or without red flags suggestive of serious pathology);

-

4.

Health care costs were reported in both study groups;

-

5.

Study was performed in the United States;

-

6.

Study was published as a full-text journal manuscript in English.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that met any of the following criteria were deemed ineligible for this review:

-

1.

Chiropractic therapy not performed by a chiropractor (e.g. SMT by a MD);

-

2.

Review article without original data;

-

3.

Abstracts, conference proceedings, presentations;

-

4.

Published prior to 1993.

Study screening

The combined search results were screened independently by two reviewers (SD and OB) based on the search records to determine relevance. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. Full-text manuscripts were obtained for studies deemed relevant or of unclear relevance.

Data extraction and analysis

The following data were extracted by one reviewer (SD) and verified by another reviewer (OB):

-

1.

Study design (e.g. location, data type, source, and dates, population size);

-

2.

Study indication (e.g. duration, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, diagnoses);

-

3.

Study groups (e.g. number and size of groups, therapy or provider involved);

-

4.

Health care and other costs (e.g. scope of costs, episodes, cost containment);

-

5.

Health care utilization (e.g. imaging, medications, hospitalization, surgery);

-

6.

Clinical outcomes data (e.g. pain severity, physical function, quality of life).

Data comparing health care costs and other costs were summarized to compare findings for study groups that received care from a doctor of chiropractic (DC) to those who received care from any other type of HCP. When data were reported for multiple subgroups of patients (e.g. different categories of spine pain), they were combined to report data for the entire study group (e.g. all patients with spine pain). Data from study groups that received both chiropractic care and care from other HCPs were assigned to the comparator group (i.e. if a study compared chiropractic care to care from both a medical physician and a chiropractor, the latter group was assigned as a comparator).

Study quality assessment

Although instruments such as the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list are available to assess the methodological quality of cost effectiveness analyses and cost utility analyses, they are not readily applicable to cost comparison studies in which clinical outcomes are not measured [21]. A modified version of the CHEC list omitting item 14 (deemed not applicable since none of the studies projected health care costs into the future) was used to assess the methodological quality of cost comparison studies also examining clinical outcomes.

Results

Search

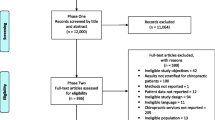

The search strategy returned 1276 citations, including 530 (42 %) from Embase, 344 (27 %) from ICL, 153 (12 %) from Medline, 88 (7 %) from the CEA registry, 67 (5 %) from NHS EED, 61 (5 %) from EconLit, and 33 (3 %) from NHS HTA. Upon combining these results, a total of 185 duplicate citations (15 %) were uncovered and removed, yielding 1091 unique citations. Screening determined that 1,020 (94 %) of these 1091 citations were not relevant; full-text articles were obtained for 71 (7 %) citations. Upon reviewing 71 full-text articles, 29 (41 %) were excluded because they were not cost comparison studies, 13 (18 %) were not related to chiropractic care, 5 (7 %) were not conducted in the US, and 2 (3 %) were not related to spine pain (note: only the primary reason for exclusion was noted; studies could be excluded for multiple reasons). In addition to the 22 (88 %) studies identified by screening search records from electronic databases, 2 (8 %) studies were identified from reference lists of previous reviews, and 1 (4 %) study was identified from author files, yielding a total of 25 eligible studies for this review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Twelve (48 %) studies examined data from private health plans in the US [22–33]. Six (24 %) studies examined data from worker’s compensation (WC) plans in the US [34–39]. Seven (28 %) studies compared both health care costs and clinical outcomes [40–46]. Findings from these three groups of studies are presented below.

Cost comparison studies in private health plans

Study design

Overall study design for the twelve studies in this group is summarized in Table 1. All studies were retrospective. Eight studies examined data from fee for service health plans, two examined health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (one study did not specify health plan type), and one study examined data from a self-funded employer. Eight studies reported the total number of members in the health plans examined, which ranged from 7706 to 2 million, while four did not report this information. Nine studies examined health care costs using 24 months of claims data, one used 12 months of data, and one used 48 months of data. Eight studies considered only LBP (as defined by 4–12 ICD-9 codes), while three included other regions of spine pain (as defined by 58–82 ICD-9 codes).

Seven studies compared health care costs for episodes of care that began with a claim for one of the ICD-9 codes of interest, six of these seven studies ended claims with a period of 35–90 days without care; five studies did not define episodes of care. Eight studies assigned all health care costs for an episode of care to the first HCP to submit a claim, while one assigned costs to the HCP who delivered the majority of care; three did not specify how they assigned costs. Six studies compared health care costs for all claims during an episode of care, while four considered only claims related to spine pain; two did not specify this. One study had five comparator groups (care from a medical physician general practitioner, internist, doctor of osteopathy, orthopedist, or other types of HCPs), one study had four comparator groups (care from a medical physician, information and advice, physical therapy, or multiple types of HCPs), one study had two comparator groups (care from a primary care medical physician or specialist), and eight studies had only one comparator (care from a medical physician). Few details were provided about the care received from different HCPs (e.g. therapies, protocols, frequency of care).

Cost comparison

Cost comparison findings for the twelve studies in this group are summarized in Table 2. Seven studies included three or more categories of health care costs (e.g. outpatient, inpatient, medications, imaging) in their comparisons, while three compared health care costs without defining the specific costs included, and two compared only outpatient health care costs (no definition provided). Ten studies compared costs paid by the health plan (i.e. costs allowed minus patient copay, coinsurance, deductible, etc.), while one compared costs allowed, and one compared costs billed by HCPs. Seven studies analyzed costs for each member with spine pain, while five analyzed costs by episode of care for spine pain (i.e. members could have multiple episodes of care). The number of members/episodes included in groups receiving chiropractic care ranged from 97 to 36,280 (mean 5149, standard deviation (SD) 10,222, median 1624), while in comparator groups it ranged from 101 to 66,158 (mean 11,456, SD 18,764, median 4910). The costs of health care for spine pain by member/episode who received chiropractic care ranged from $264 to $6,171 (mean $2,022, SD $2,332, median $712), while in comparator groups it ranged from $166 to $9,958 (mean $3,375, SD $3,481, median $1,992). In eleven (92 %) studies, health care costs were lower for patients whose spine pain was managed with chiropractic care. The difference in health care costs for members who received chiropractic care ranged from −70 % to 59 % (mean −36 %, SD 33 %, median −38 %).

Cost comparison studies in worker’s compensation plans

Study design

Overall study design for the six studies in this group is summarized in Table 3; additional information (i.e. members included in analysis) was obtained from a secondary report [47]. Five studies were retrospective and one was prospective. Two studies examined data from private WC plans, one from a self-insured employer WC plan, one from a quasi-state agency for WC, one from a state WC plan, and one from a nonprofit WC plan. Five studies examined only claims data, while one study also included billing data from HCPs and data collected from patients. Only 1/6 (16 %) studies reported the total number of members covered by the WC plan examined (n = 96,627). Two studies examined only claims related to LBP, while four examined claims for all regions of spine pain; only one study reported the ICD-9 codes used to define spine pain.

Three studies examined only closed claims related to spine pain, two examined claims at least 1 year from the date of onset (% closed claims not reported), and one examined claims at least 2 years from the date of onset (97 % were closed). The number of members who met stated eligibility criteria ranged from 1831 to 80,615 (mean 29,556, SD 32,694, median 11,420). The duration of claims data examined ranged from 12 to 239 months (mean 66.5, SD 85.8, median 38.9). The delay between the end of the data period examined and study publication ranged from 4.3 to 10.0 years (mean 6.9, SD 1.9, median 6.7). One study had five comparator groups (care from a medical physician, care from a PT, care from both a medical physician and PT, other care, or no care), one had four comparator groups (care from a medical physician, care from a medical physician and chiropractor, care from a medical physician and PT, or care from other HCPs), one study had three comparator groups (care from a medical physician, medical physician and chiropractor, and no care), and three studies had one comparator group (care from a medical physician). Few details were provided about the care received from different HCPs (e.g. therapies, protocols, frequency of care). One study compared health care costs for patients who had received chiropractic care during both the disability period (i.e. time when they were not working due to spine pain) and after the disability period (i.e. once they had returned to work, defined as the “maintenance period” in that study) [37].

Cost comparison

Cost comparison findings for the six studies in this group are summarized in Table 4. All of the studies considered only health care costs related to spine pain, and all compared the amounts paid by WC plans (i.e. not billed by HCPs). Three studies included four or more categories of health care costs (e.g. office visits to DC/MD/PT, medications, imaging) in their comparisons, while three studies included all health care costs without defining the specific costs included. The number of members/claims included in groups receiving chiropractic care ranged from 54 to 1007 (mean 275, SD 362, median 166), while in comparator groups it ranged from 671 to 10,930 (mean 2988, SD 3966, median 1605). The costs of health care for spine pain by member/claim who received chiropractic care ranged from $415 to $1,296 (mean $817, SD $320, median $777), while in comparator groups it ranged from $264 to $7,904 (mean $2,565, SD $3,137, median $867). In five (83 %) studies, health care costs were lower for patients whose spine pain was managed with chiropractic care. The difference in health care costs for members who received chiropractic care ranged from −91 % to 229 % (mean 4 %, SD 116 %, median −18 %).

Cost comparison studies also examining clinical outcomes

Study design

Overall study design for the seven studies in this group is summarized in Table 5; additional information (i.e. eligibility criteria) was also obtained from secondary reports [48–50]. Four studies were based on observational (OBS) designs (i.e. comparative cohorts), while three were based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Of the four OBS studies, three examined patients with LBP who received care at one of 51 chiropractic clinics and 14 medical clinics in Oregon and Washington, while the other examined patients who sought care for LBP from different HCPs in North Carolina. Two of the RCTs enrolled patients seeking care at health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in California and Washington, while one enrolled patients at a chiropractic college outpatient clinic in Minnesota. All seven studies were focused on LBP, including LBP of any duration (n = 4), LBP present for less than 10 weeks (n = 1) or 12 weeks (n = 1), and LBP for more than 7 days (n = 1). Four studies stated they enrolled participants with nonspecific LBP (e.g. LBP of mechanical origin), while four studies excluded participants with potential red flags for serious spinal pathology (e.g. cancer, instability).

Five studies reported that patients in the chiropractic care groups received a variety of therapies, including SMT, exercise, and physical modalities (e.g. heat, cold, massage, ultrasound, electrical stimulation), while one study stated only SMT and one study did not specify the therapies received. Two of the studies included multiple groups who received chiropractic care (e.g. urban vs. rural chiropractic care, chiropractic care with or without physical modalities). One study had four comparator groups (care from an urban or rural medical physician, care from an orthopedist, or care from a nurse practitioner (NP) or physician’s assistant (PA)), four studies had two comparator groups (care from a medical physician with or without referral to PT or surgeon, care from a PT or educational booklet about LBP, care from a medical physician with or without physical modalities, care from a medical physician or epidural steroid injection), and one study had only one comparator (care from a medical physician).

Cost comparison

Cost comparison findings for the seven studies in this group are summarized in Table 6. Four studies estimated health care costs from amounts billed by HCPs, two studies did so from internal cost accounting systems, and one study did not report how health care costs were estimated. All seven studies specified that office visits were included in health care costs; studies also included the costs of diagnostic imaging (n = 5), medication (n = 3), PT (n = 3), surgical care or referral (n = 3), and injections (n = 2). The number of participants included in groups receiving chiropractic care ranged from 7 to 1,855 (mean 857, SD 768, median 606), while in comparator groups it ranged from 13 to 1,027 (mean 568, SD 387, median 739). The costs of health care for spine pain by participants who received chiropractic care ranged from $214 to $684 (mean $411, SD $194, median $429), while in comparator groups it ranged from $123 to $1,285 (mean $474, SD $401, median $343). In two (29 %) studies, health care costs were lower for patients whose LBP was managed by chiropractic care. The difference in health care costs for members who received chiropractic care ranged from −57 % to 74 % (mean 10 %, SD 40 %, median 8 %).

Study quality assessment

Assessment of methodological quality for the seven studies in this group is summarized in Table 7. The number of questions on the CHEC list that could be answered “yes” ranged from 7 to 14 (mean 10.1, SD 2.3, median 10). The questions most commonly scored as “yes” were items 4, 11, 16, and 18, which were present in all seven studies. The questions most commonly scored as “no” items were items 12, 14, and 19, none of which were present in any of the seven studies.

Comparison of clinical outcomes

The clinical outcomes examined in these seven studies included pain (n = 6), physical function (n = 6), and patient satisfaction (n = 4). Among the six studies that measured pain, only two reported significant differences between the groups compared. In one study, participants who received chiropractic care had greater improvement in pain than those who received care from a medical physician after both 3 months and 12 months [41]. In another study, chiropractic care had greater improvement in pain than an educational booklet about LBP after 1 month, but not after 3, 12, or 24 months; after adjusting for baseline variables, the difference in pain after 1 month was no longer significant [44]. One study did not report differences in pain between groups due to the limited sample size (i.e. n = 20) [46].

In the six studies that measured physical function, only one study reported significant differences between the groups compared. In that study, participants who received chiropractic care had greater improvement in physical function after both 3 months and 12 months than those who received care from a medical physician [41]. Three of the four studies that measured patient satisfaction reported differences between the groups compared. In two studies, participants who received chiropractic care were more satisfied than those who received care from a medical physician [40, 41]. In another study, participants who received chiropractic care (or care from a PT) were more satisfied than those who received an educational booklet about LBP [44]. One study did not report differences in satisfaction between groups due to the limited sample size (i.e. n = 20) [46].

Adjusted vs. unadjusted cost comparisons

Ten studies (42 %) reported adjusting their comparison of health care costs to account for differences that may have existed between study groups in sociodemographics or clinical factors (e.g. patients receiving chiropractic care having less severe symptoms than those receiving care from a medical physician); their findings are summarized in Table 8 [22–24, 28, 31, 32, 39–41, 45]. The most commonly used factors to adjust these findings included patient location (n = 5), age (n = 4), gender (n = 4), physical function (n = 3), pain (n = 3), type of health insurance (n = 3), and comorbidities (n = 3). Before adjusting for various factors, 6/10 (60 %) studies reported that health care costs for spine pain were lower with chiropractic care than comparator groups; this proportion remained constant after adjusting for differences between groups. However, one study that reported unadjusted health care costs were lower with chiropractic care noted that adjusted health care costs were in fact lower for the comparator groups, and another study reported the opposite.

Discussion

This review identified 25 cost comparison studies published in English since 1993 that were related to chiropractic care for spine pain in the US. The largest group of studies examined data from private health plans (n = 12), while smaller groups of studies examined data from WC plans (n = 6), or also examined clinical outcomes (n = 7). There were notable differences in study design not only between these three groups of studies, but also among studies within these groups; each group is briefly discussed below.

Overall, 11/12 (92 %) studies in private health plans reported that health care costs were lower for members whose spine pain was managed by chiropractic care, by a mean of 36 %. It should be noted that the only study reporting higher health care costs with chiropractic care was also the only study to examine costs billed by HCPs rather than costs allowed or paid by health plans. It is unknown if differences that may exist in the amounts billed, allowed, and paid by HCPs may have influenced this finding (e.g. DCs may bill more but be paid a smaller amount) [31]. It should also be noted that 7/12 (58 %) studies in this group were conducted by the same author (Miron Stano, PhD) and appeared to use the same source for private health plan claims data (MEDSTAT), raising the possibility of duplicate or unusually homogeneous study findings.

Differences in studies examining data from private health plans were found in the type of spine pain (e.g. LBP only, all regions of spine pain), definition of spine pain (e.g. number of ICD-9 codes included), size of the population size studied, length of claims data (e.g. 12 vs. 24 vs. 48 months), age of claims data (e.g. from 1988 to 2006), focus on members or episodes of care, definition of episodes of care (e.g. no care for 35 vs. 90 days), assignment of health care costs to HCPs (e.g. first HCP seen vs. HCP who gave majority of care), focus on patients with single vs. multiple episodes of care, scope of health care costs (e.g. all conditions vs. spine only), and categories of health care costs examined (e.g. office visits/outpatient care/inpatient care/medications). Not surprisingly, large differences were therefore found in health care costs for both members who received chiropractic care (lowest $264, highest $6,171) or comparator groups (lowest $166, highest $9,958). Furthermore, few details were provided about the actual care received for spine pain from different HCPs. For example, while some readers may assume that chiropractic care consisted primarily of guideline-endorsed therapies such as SMT, patient education, and supervised exercise, such care could also have been provided by medical physicians, PTs, or other HCPs, making comparisons difficult based on the type of HCP seen.

Similar differences were also noted in the design of six cost comparison studies examining data from WC plans, as well as the inclusion or exclusion of patients who underwent spine surgery, examination of open vs closed WC claims, adherence to the different HCPs compared (e.g. patients who remained loyal to one type of HCP vs. those who switched), types of WC claims (e.g. medical only vs. temporary or permanent disability), and examination of health care costs both during and after the period of disability (e.g. so-called “maintenance” care). Although health care costs in groups who received chiropractic care were somewhat similar across these six studies (lowest $415, highest $1,296), large differences were noted in the comparator groups (lowest $264, highest $7,904). Few details were provided about how state regulations of health care for WC claims may have impacted differences in health care costs (e.g. period during which employer has choice of HCPs vs. employee, proportion of earnings covered while on disability). It is also important to note that while indirect costs (e.g. lost productivity) account for a majority of the total costs of spine pain they are difficult to measure and often complex. Only 5/25 (20 %) measured these costs; they were generally lower for patients receiving chiropractic care [33, 35, 36, 38].

It is interesting that most cost comparison studies based on administrative claims data (e.g. private health plans or WC plans) reported that health care costs were generally lower for members/workers whose spine pain was managed with chiropractic care. However, in studies that also examined clinical outcomes and therefore had richer sources of clinical data than studies based only on administrative claims, the reverse was noted and health care costs were generally higher among patients who received chiropractic care. It is unknown if this difference is related to the intensity or type of health care received in pragmatic “real-world” studies (e.g. retrospective examination of administrative claims data) when compared to prospective, comparative cohorts or RCTs in which HCPs attempt to follow specific treatment protocols. Somewhat less variation was noted among these seven studies in the health care costs of participants who received chiropractic care (lowest $214, highest $684) or comparators (lowest $123, highest $1,285) than studies examining private health plans or WC plans.

Few health economic evaluations (HEEs) reported the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for pain, function, and patient satisfaction, despite renewed interest in such measures to help determine the value of various health care interventions. Although the ICERs that were estimated from the data reported appeared quite small (i.e. $1-10 per 1-point difference in 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS)), the willingness to pay (WTP) for such outcomes in patients with spine pain is unclear. It may be worthwhile to explore various WTP thresholds for such measures from different perspectives (including the patient’s) in future economic evaluations, perhaps as part of efforts to implement value-based health benefits insurance design for spine pain [51].

The methodological quality of the seven studies also examining clinical outcomes was suboptimal, with 8/19 (42 %) items on the CHEC instrument being absent in a majority of studies. No apparent relationship was observed between methodological quality and differences in health care costs reported between study groups. It should be noted that only one study scored a “yes” on item 9 “Are costs valued appropriately?” and all studies scored a “no” on item 12, “Are outcomes valued appropriately?” This is a limitation that should be addressed in future evaluations as only one study based costs on resource utilization and no study provided health-related utility estimates.

Generally few differences were reported between study groups in the efficacy of different approaches to managing spine pain, whether chiropractic care, care from a medical physician, care from a PT, or an educational booklet about LBP. These findings are consistent with conclusions from recent systematic reviews suggesting that the efficacy of SMT (e.g. most commonly used by chiropractors) for acute and chronic LBP is likely comparable to that of other recommended conservative approaches, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, or self-care [52, 53]. Previous reviews have also highlighted the methodological weaknesses of economic evaluations related to spine pain, concluding that the health outcomes achieved with chiropractic care were similar to various comparators, with small differences in costs [12, 14, 54].

In general, the findings in this review suggest that health care costs may be somewhat lower when spine pain is managed with chiropractic care in the US, even if such differences are sometimes attributable to sociodemographics, clinical, or other factors rather than HCPs. These findings echo that of a review published in 1993 that examined studies in which LBP was managed by SMT, chiropractic care, other interventions (e.g. physical modalities, medications, exercise) throughout the world (e.g. Australia, Canada, Egypt, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Sweden, United Kingdom, and US) [11]. Based on the favorable short-term clinical improvements and lower costs of care reported in those studies, the previous review concluded that health care costs could be reduced if a higher proportion of patients with spine pain received chiropractic care rather than other interventions, and recommended a greater integration of chiropractors into the publicly financed health care system in Ontario, Canada. However, that recommendation was never implemented, and publicly financed coverage of chiropractic services (and other health care services) was subsequently eliminated in Ontario to alleviate budget deficits [55]. A more recent review was published on the clinical and economic evidence on chiropractic care for the management of LBP in 2005 [56]. The study found that although outcomes were similar between chiropractic care and standard medical care, the evidence remained inconclusive for costs.

Recent studies have assessed the efficacy of integrating chiropractic care for spine pain into the mainstream health care system with mixed results. For example, a study in Vancouver, Canada, compared the clinical outcomes of patients who received evidence-based care, including chiropractic care, for LBP in a hospital setting to usual care from a primary care provider (PCP) [57]. Findings suggested that usual care from a PCP was rarely evidence-based, with many patients receiving bed rest, opioids, and passive physical modalities, and few receiving exercise and reassurance. After 6 months, patients who received chiropractic care were more likely to improve than those receiving usual care from a PCP; costs were not measured. Other studies have reported similarly favorable clinical or economic results in both Canada (i.e. Calgary, Ottawa) and the US (i.e. Boston) [58–61]. However, a recent study that increased Medicare coverage of chiropractic care to allow additional health services (e.g. physical modalities and procedures, x-rays, referrals for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) and diagnoses (e.g. neuromuscular conditions) in parts of Maine, New Mexico, northern Illinois, Iowa, and Virginia reported that this increased total health care costs [62]. Although a subsequent analysis reported that the vast majority of cost-increases occurred in only one of the demonstration areas (i.e. northern Illinois), the demonstration project was not deemed successful and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) did not pursue expanded coverage of chiropractic care to reduce health care costs [63].

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review, which only examined studies published in English conducted in the US, limiting its generalizability in other settings. As noted above, the studies reviewed differed widely in their methodology, which presents challenges when interpreting and comparing their findings. Studies evaluated in the manuscript only evaluated costs from a third party payer perspective. Whereas evaluations from a societal and governmental perspective are generally preferable, few studies have access to such comprehensive data when comparing costs.

Although health care costs from the studies included could have been presented in constant 2015 dollars using published US health care inflation factors, doing so over an extended period (e.g. 1988 to 2006) would likely have masked other important differences in US health care costs during that time, including changes in health plan types (e.g. fee for service vs. HMO), therapies used to manage spine pain (e.g. passive vs. active care), health plan coverage of therapies (e.g. motorized traction therapy), fees for specific therapies (e.g. bundled vs. itemized billing), health plan cost sharing (e.g. copays, coinsurance, deductibles), coverage limits (e.g. annual visits to specific HCPs), and cost containment methods (e.g. prior authorization). Therefore, the original costs reported in each study are presented in this review and as such, are not easily compared across studies. In addition, this review aggregated data to present single estimates related to health care costs for those who received chiropractic care or other comparators, which may have masked important differences noted in study subgroups. Three of the authors are trained as chiropractors, which may create some bias, and were formerly consultants of a specialty managed care company in the US (Palladian Health).

Conclusions

This review identified 25 cost comparison studies related to chiropractic care for spine pain in the US and published in English since 1993. Although findings from the studies reviewed generally suggested that chiropractic care may be associated with lower health care costs when compared to care from other HCPs, the methods used in these studies differed widely, limiting their interpretation and generalizability. Additional research using more rigorous methods is needed to determine if differences in health care costs noted in these studies are attributable to the type of health care received for spine pain or patient sociodemographic, clinical, or other factors that may be unrelated to health care.

Abbreviations

- US:

-

United States

- HCP:

-

Health care provider

- WC:

-

Workers’ compensation

- CHEC:

-

Consensus on health economic criteria

- MD:

-

Medical doctor

- DO:

-

Doctor of osteopathy

- PT:

-

Physical therapist

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- SMT:

-

Spinal manipulation therapy

- CPG:

-

Clinical practice guideline

- CAM:

-

Complementary and alternative medical

- EED:

-

Economic evaluation database

- HTA:

-

Health technology assessment

- ICL:

-

Index to chiropractic literature

- DC:

-

Doctor of chiropractic

- HMO:

-

Health maintenance organizations

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- OBS:

-

Observational

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- NP:

-

Nurse practitioner

- PA:

-

Physician’s assistant

- HEE:

-

Health economic evaluations

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- WTP:

-

Willingness to pay

- NSAID:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PCP:

-

Primary care provider

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CMS:

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services

References

Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA. The most expensive medical conditions in America. Health Aff. 2002;21:105–11.

Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S. The health and productivity cost burden of the “top 10” physical and mental health conditions affecting six large U.S. employers in 1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:5–14.

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:2443–54.

Chevan J, Riddle DL. Factors associated with care seeking from physicians, physical therapists, or chiropractors by persons with spinal pain: a population-based study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:467–76.

Hurwitz E, Coulter I, Adams A, Genovese B, Shekelle P. Use of chiropractic services from 1985 through 1991 in the United States and Canada. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:771–6.

Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening Trends in the Management and Treatment of Back Pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573–81. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8992.

Smucker DR, Konrad TR, Curtis P, Carey TS. Practitioner self-confidence and patient outcomes in acute low back pain. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(3):223–8.

Cherkin DC, MacCornack FA, Berg AO. Managing low back pain--a comparison of the beliefs and behaviors of family physicians and chiropractors. West J Med. 1988;149(4):475–80.

Gaumer G. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with chiropractic care: survey and review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(6):455–62. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.06.013.

Chapman-Smith D. Cost-Effectiveness Revisited. The Chiropractic Report. 2009;23(6):1–8.

Manga P, Angus D, Papadopoulos C. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of chiropractic management of low-back pain. Toronto, ON: Kenilworth Publishers; 1993.

Baldwin ML, Cote P, Frank JW, Johnson WG. Cost-effectiveness studies of medical and chiropractic care for occupational low back pain. A critical review of the literature. Spine J. 2001;1:138–47.

Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Deyo RA, Shekelle PG. A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety, and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:898–906.

Michaleff ZA, Lin CW, Maher CG, van Tulder MW. Spinal manipulation epidemiology: Systematic review of cost effectiveness studies. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22(5):655–62.

Lin CW, Haas M, Maher CG, Machado LA, van Tulder MW. Cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for low back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2011; Published online January 13, 2011.

Driessen MT, Lin CW, van Tulder MW. Cost-effectiveness of conservative treatments for neck pain: a systematic review on economic evaluations. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1441–50.

Furlan A, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, Gross A, van Tulder MW, Santaguida L, et al. Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Back Pain II (Prepared by the University of Ottawa Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10059-I). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2009;34:1929–41.

Glanville J, Fleetwood K, Yellowlees A, Kaunelis D, Mensinkai S. Development and testing of search filters for economic evaluations in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2009.

Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:240–5.

Stano M. A comparison of health care costs for chiropractic and medical patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16:291–9.

Stano M. The economic role of chiropractic: further analysis of relative insurance costs for low back care. JNMS. 1995;3(3):139–44.

Stano M. Further analysis of health care costs for chiropractic and medical patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:442–6.

Stano M. The economic role of chiropractic: an episode analysis of relative insurance costs for low back care. JNMS. 1993;1(1):64–8.

Stano M. Overview of the ACA cost of care analysis project. J Chiropr. 1993;30(3):41–5.

Smith M, Stano M. Costs and recurrences of chiropractic and medical episodes of low-back care. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:5–12.

Stano M, Smith M. Chiropractic and medical costs of low back care. Med Care. 1996;34:191–204.

Grieves B, Menke JM, Pursel KJ. Cost minimization analysis of low back pain claims data for chiropractic vs medicine in a managed care organization. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32:734–9.

Mosley CD, Cohen IG, Arnold RM. Cost-effectiveness of chiropractic care in a managed care setting. Am J Manag Care. 1996;2:280.

Shekelle PG, Markovich M, Louie R. Comparing the costs between provider types of episodes of low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:221–6.

Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM. Cost of care for common back pain conditions initiated with chiropractic doctor vs medical doctor/doctor of osteopathy as first physician: experience of one Tennessee-based general health insurer. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:640–3.

Allen H, Wright M, Craig T, Mardekian J, Cheung R, Sanchez R, et al. Tracking low back problems in a major self-insured workforce: toward improvement in the patient’s journey. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(6):604–20. doi:10.1097/jom.0000000000000210.

Johnson WG, Baldwin ML, Butler RJ. The costs and outcomes of chiropractic and physician care for workers’ compensation back claims. J Risk Insur. 1999;66:185–205.

Gilkey D, Caddy L, Keefe T, Wahl G, Mobus R, Enebo B, et al. Colorado workers’ compensation: medical vs chiropractic costs for the treatment of low back pain. J Chiropr Med. 2008;7:127–33.

Phelan SP, Armstrong RC, Knox DG, Hubka MJ, Ainbinder DA. An evaluation of medical and chiropractic provider utilization and costs: treating injured workers in North Carolina. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27:442–8.

Cifuentes M, Willetts J, Wasiak R. Health maintenance care in work-related low back pain and its association with disability recurrence. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53:396–404.

Jarvis KB, Phillips RB, Danielson C. Managed care preapproval and its effect on the cost of Utah worker compensation claims. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:372–6.

Butler RJ, Johnson WG. Adjusting rehabilitation costs and benefits for health capital: the case of low back occupational injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:90–103.

Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, McLaughlin C, Fryer J, Smucker DR. The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:913–7.

Haas M, Sharma R, Stano M. Cost-effectiveness of medical and chiropractic care for acute and chronic low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:555–63.

Stano M, Haas M, Goldberg B, Traub PM, Nyiendo J. Chiropractic and medical care costs of low back care: results from a practice-based observational study. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:802–9.

Sharma R, Haas M, Stano M, Spegman A, Gehring R. Determinants of costs and pain improvement for medical and chiropractic care of low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32:252–61.

Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battie M, Street J, Barlow W. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1021–9.

Kominski GF, Heslin KC, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, Harber PI. Economic evaluation of four treatments for low-back pain: results from a randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 2005;43:428–35.

Bronfort G, Evans RL, Anderson AV, Schellhas KP, Garvey TA, Marks RA, et al. Nonoperative treatments for sciatica: a pilot study for a randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:536–44.

Cote P, Baldwin ML, Johnson WG. Early patterns of care for occupational back pain. Spine. 2005;30:581–7.

Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goldberg B, Sexton G. Pain, disability, and satisfaction outcomes and predictors of outcomes: a practice-based study of chronic low back pain patients attending primary care and chiropractic physicians. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:433–9.

Hertzman-Miller RP, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, Yu F, Adams AH, Harber P, et al. Comparing the satisfaction of low back pain patients randomized to receive medical or chiropractic care: results from the UCLA low-back pain study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1628–33.

Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Harber P, Kominski GF, Belin TR, Yu F, et al. A randomized trial of medical care with and without physical therapy and chiropractic care with and without physical modalities for patients with low back pain: 6-month follow-up outcomes from the UCLA low back pain study. Spine. 2002;27:2193–204.

Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Value-based insurance design. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):w195–203. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w195.

Rubinstein SM, Terwee CB, Assendelft WJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low back pain: an update of the cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(3):E158–77. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827dd89d.

Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW. Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD008112.

Choudhry N, Milstein A. Do chiropractic physician services for treatment of low back and neck pain improve the value of health benefit plans? An evidence-based assessment of incremental impact on population health and total health care spending: Mercer. 2009.

Longo M, Grabowski M, Gleberzon B, Chappus J, Jakym C. Perceived effects of the delisting of chiropractic services from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan on practice activities: a survey of chiropractors in Toronto, Ontario. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55(3):193–203.

Brown A, Angus D, Chen S, Tang A, Milne S, Pfaff J, et al. Costs and outcomes of chiropractic treatment for low back pain [Technology report no 56]. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment; 2005.

Bishop PB, Quon JA, Fisher CG, Dvorak MF. The Chiropractic Hospital-based Interventions Research Outcomes (CHIRO) study: a randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of clinical practice guidelines in the medical and chiropractic management of patients with acute mechanical low back pain. Spine J. 2010;10:1055–64.

McMorland G, Suter E, Casha S, du Plessis SJ, Hurlbert RJ. Manipulation or microdiskectomy for sciatica? A prospective randomized clinical study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:576–84.

Paskowski I, Schneider M, Stevans J, Ventura JM, Justice BD. A hospital-based standardized spine care pathway: report of a multidisciplinary, evidence-based process. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34:98–106.

Garner MJ, Aker P, Balon J, Birmingham M, Moher D, Keenan D, et al. Chiropractic care of musculoskeletal disorders in a unique population within Canadian community health centers. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(3):165–70. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.01.009.

Garner MJ, Birmingham M, Aker P, Moher D, Balon J, Keenan D, et al. Developing integrative primary healthcare delivery: adding a chiropractor to the team. Explore. 2008;4:18–24.

Stason WB, Ritter G, Shepard DS, Tompkins C, Martin TC, Lee S. Evaluation of the Demonstration of Expanded Coverage of Chiropractic Services under Medicare. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2010.

Weeks WB, Whedon JM, Toler A, Goertz CM. Medicare’s Demonstration of Expanded Coverage for Chiropractic Services: Limitations of the Demonstration and an Alternative Direct Cost Estimate. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36(8):468–81. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.07.003.

Newhouse JP, Manning WG, Morris CN, Orr LL, Duan N, Keeler EB, et al. Some interim results from a controlled trial of cost sharing in health insurance. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(25):1501–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM198112173052504.

Allen H, Rogers WH, Bunn WB, Pikelny DB, Naim AB. Reducing total health burden from 2001 to 2009: an employer counter-trend success story and its implications for health care reform. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(8):904–16. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318267f1b1.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the NCMIC Foundation for their financial support in completing this study. The NCMIC Foundation is a nonprofit organization focused on research and educational projects relating to chiropractic care. The funding source had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

SD: Royalties: Elsevier; Stock Ownership: Pacira Pharmaceuticals; Private Investments: Palladian Health; Consulting: University of South Florida, NCMIC Foundation, Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Palladian Health; Speaking and/or Teaching Arrangements: NCMIC Foundation; Trips/Travel: North American Spine Society (NASS); Scientific Advisory Board: Societe Franco-Europenne de Chiropraxie (SOFEC), Palladian Health; Employment: Pacira Pharmaceutical; Grants: NCMIC Foundation.

OB: Consulting: Palladian Health (C), Spine Research LLC (B), World Spine Care (B), Trip/Travel: Palladian Health (B).

SH: Royalties: Elsevier (A); Private Investments: Palladian Health (<2 % of common shares; value unknown); Private practice. Consulting: Palladian Health (F); Other Office (non-financial): North American Spine Society (NASS), World Spine Care (WSC), National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM).

PM: Nothing to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

SD conceived the study, designed the review protocol, sought funding, provided critical analysis and interpretation of data, was responsible for acquisition of data, and took primary responsibility of drafting the manuscript. OB provided critical analysis and interpretation of data and contributed to acquisition of data. SH contributed to conception and design of the review protocol and sought funding. PM provided critical analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read, made critical revisions, and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Medline search strategy. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dagenais, S., Brady, O., Haldeman, S. et al. A systematic review comparing the costs of chiropractic care to other interventions for spine pain in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res 15, 474 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1140-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1140-5