Abstract

Background

Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of low back pain suggest the inclusion of a biopsychosocial approach in which patient self-management is prioritized. While many physiotherapists recognise the importance of evidence-based practice, there is an evidence practice gap that may in part be due to the fact that promoting self-management necessitates change in clinical behaviours. Evidence suggests that a patient’s motivation and maintenance of self-management behaviours can be positively influenced by the clinician’s use of an autonomy supportive communication style. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop and pilot-test the feasibility of a theoretically derived implementation intervention to support physiotherapists in using an evidence-based autonomy supportive communication style in practice for promoting patient self-management in clinical practice.

Methods

A systematic process was used to develop the intervention and pilot-test its feasibility in primary care physiotherapy. The development steps included focus groups to identify barriers and enablers for implementation, the theoretical domains framework to classify determinants of change, a behaviour change technique taxonomy to select appropriate intervention components, and forming a testable theoretical model. Face validity and acceptability of the intervention was pilot-tested with two physiotherapists and monitoring their communication with patients over a three-month timeframe.

Results

Using the process described above, eight barriers and enablers for implementation were identified. To address these barriers and enablers, a number of intervention components were selected ranging from behaviour change techniques such as, goal-setting, self-monitoring and feedback to appropriate modes of intervention delivery (i.e. continued education meetings and audit and feedback focused coaching). Initial pilot-testing revealed the acceptability of the intervention to recipients and highlighted key areas for refinement prior to scaling up for a definitive trial.

Conclusion

The development process utilised in this study ensured the intervention was theory-informed and evidence-based, with recipients signalling its relevance and benefit to their clinical practice. Future research should consider additional intervention strategies to address barriers of social support and those beyond the clinician level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Low back pain (LBP) has recently been ranked as the leading cause of disability worldwide [1]. Within Ireland, it has been estimated that 395,000 or 11.9 % of people aged 18 years and over had a chronic back condition in 2010 [2]. While no “cure” using traditional therapeutic approaches has been identified, current clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) promote a self-management approach as best practice [3–5]. Non-pharmacological self-management strategies such as exercise [3] are based on high quality evidence derived from randomized controlled trials and represent current best practice for this condition. However, promoting self-management necessitates a change in the clinical behaviours of many healthcare professionals (HCPs) trained to use a biomedical approach [6]. For example, promoting self-management involves the clinician to act as a co-regulator in the treatment process working in partnership with the patient to take responsibility for their symptom management rather than using a traditional biomedical approach to care. Thus, a major challenge with uptake of CPGs is changing HCP behaviour to support patient autonomy to adopt a self-management approach [7].

Evidence suggests that HCPs can influence patients’ motivation and ultimately their maintenance of health-conducive behaviours through their communication style and adoption of a patient centred approach [8]. This approach based on self-determination theory (SDT) [9] proposes that autonomous motivation leads to greater persistence with the targeted behaviour and enhanced psychological wellbeing whereas controlled motivation can result in poor long term engagement with the targeted behaviour. According to SDT, autonomous motivation is characterised by self-endorsement of the behaviour and a belief in its value while controlled motivation typically relates to engaging in a behaviour due to feelings of guilt or external pressures such as coercion. The development of autonomous motivation can occur through the social environment and the autonomy supportive communication behaviour of a significant other [10]. In a health context, the concept of autonomy supportive communication behaviour represents an interpersonal climate whereby the HCP places the patient at the centre of the treatment experience, for example, taking the perspective of the patient into account, providing relevant information and opportunities for patient input and choice [10].

Recently, several interventions across different populations have supported the use of SDT derived communication behaviours by HCPs to promote a patient’s active role in the treatment process and ultimately their maintenance of health-conducive behaviours, including medication adherence [11], physical activity [12], smoking cessation [13] and dental hygiene [14]. More recently, SDT was used to develop a series of communication strategies as an intervention to improve the management of low back pain in physiotherapy settings; specifically the strategies were aimed at improving patients’ autonomous motivation to increase and maintain their physical activity levels. Full details of the 18 communication strategies used in the intervention entitled the Communication Style and Exercise Compliance in Physiotherapy (CONNECT) trial can be found in the study protocol [15]. Initial evidence from this trial found that physiotherapists who completed the CONNECT training provided greater autonomy support for patients’ needs compared to physiotherapists who had no training [16].

Although, there is evidence to support the effectiveness of this autonomy supportive communication style, adopting this behaviour in clinical practice may prove challenging without the addition of appropriate education or training resources. Recent Cochrane systematic reviews have recommended [a] continuing education meetings [17], [b] educational outreach visits [18], [c] local opinion leaders [19] and [d] audit and feedback [20] as effective evidence-based strategies to change professional practice. While, a multi-faceted approach to changing healthcare professional behaviour is recommended, many studies have failed to prospectively identify barriers to implementing interventions thus limiting their effectiveness. Furthermore, research of the methods used to identify barriers and tailor interventions to address them has been advocated by the Cochrane collaboration [21]. Commonly reported barriers to implementing evidence in practice are lack of appropriate skills, lack of support and time constraints [22–24]; however, specific barriers relating to the use of SDT-based communication strategies have not been identified. Consequently, there is a need to focus on identifying barriers and then developing and evaluating evidence-based interventions to support knowledge mobilization and effective implementation [25]. To support this process, tailored interventions that aim to change clinician behaviour and to support the uptake of evidence into practice are recommended [26].

The increasingly used Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) provides a validated systematic, theoretically derived framework of 14 domains for identifying the main factors believed to enhance or impede practitioner behaviour change, for example, knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, optimism and professional identify [27], as well as facilitating the selection of evidence-based strategies to address them. Indeed, the TDF has been applied to a small number of studies examining LBP and osteoarthritis [28–30]. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to develop a pragmatic intervention for changing provider behaviour; specifically the Knowledge Exchange and Delivery Support (KEDS) intervention for changing physiotherapist behaviour relative to communication strategies with back pain patients. A secondary purpose of the study was to pilot-test our protocol for implementing the KEDS intervention within a clinical setting to obtain preliminary data in order to identify its acceptability and make any necessary refinements.

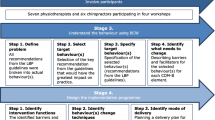

Figure 1. Presents the theoretical rationale underpinning the development of KEDS as an intervention to support the uptake of evidence-based communication strategies used in the CONNECT trial [15].

Methods

This study took place within primary care clinics in the greater Dublin region providing acute and chronic care. It was approved by the appropriate Research Ethics Committee for primary care services in the greater Dublin region. All participants provided written consent prior to taking part in the study.

Phase 1 - initial development of the KEDS intervention

To inform the development of the intervention, two focus groups were conducted with a purposive sample of primary care physiotherapists (n = 9) who had training and experience using the target behaviour in practice as part of the study entitled the CONNECT trial [15]. The TDF was used to inform the focus group interview guide in order to identify the barriers (and enablers) to implementing the SDT-based communication behaviour change. Both focus groups were led by an experienced qualitative researcher (SG) who explored the reasons why physiotherapists did/did not use particular communication strategies during individual LBP patient management. Questions were developed to specifically explore the TDF domains for the targeted behaviour. The results provided detailed information regarding key barriers and enablers to implementing the communication strategies in practice.

Specifically, eight barriers and enablers were identified across organizational, managerial/administration, physiotherapist and patient levels. These barriers and enablers were reviewed by the research team and agreement was reached as to which could be reasonably targeted within the KEDS intervention. For example, it was agreed that the barriers related to the domains, environmental context and resources (e.g. lack of resources or long waiting lists) and social/professional role and identify (at the patient level, e.g. patient expectations of passive treatment) were beyond the scope of this study. Consequently, six barriers and enablers were identified as modifiable and feasible to address within the KEDs intervention. These included physiotherapist knowledge, skills, social influence, professional role, beliefs about capabilities and behavioural regulation.

Using a combination of theory and evidence, intervention components which could address the selected barriers and enablers were then chosen by the research team. First, specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs) for each modifiable barrier and enabler were chosen using a matrix [31] which enables the mapping of BCTs to theoretical domains. Second, the mode of delivery was selected based on a review of recent evidence [e.g. Cochrane systematic reviews; 17–20], with the aim of maximising BCT implementation within the intervention. Finally, to ensure the components were likely to be feasible, acceptable and locally relevant, primary care physiotherapy managers were consulted regarding the proposed behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery. No changes to the intervention components were required based on this consultation process.

The proposed KEDs intervention

A list of the targeted barriers and enablers and their associated evidence-informed components included in KEDs intervention can be found in Table 1. In short, these were:

-

(i)

Continuing education meeting: The once –off education meeting was designed in line with recommendations from a Cochrane review (e.g. a facilitated group workshop, using both didactic and interactive methods) [17]. The BCTs selected for implementation in this part of the intervention included, information regarding the targeted behaviour, social process of encouragement and support, persuasive communication and goal-setting. These components aimed to target domains such as knowledge, skills, social influence, professional role and identity (physiotherapist level). This meeting was scheduled to last 2.5 h and was open to all physiotherapists within the primary care site. A registered Psychologist (JM) and chartered Physiotherapist (DH) who had experience in using these communication strategies and had published related research in peer reviewed journals in the last five years, facilitated the meeting. Broadly, the meeting began with an introduction to the theory and evidence for the SDT-based communication strategies. This was followed by group based discussions/exercises as to how these strategies could be used in practice. Finally, practical steps as to how to implement these communication strategies in practice were identified and shared by the participating physiotherapists.

-

(ii)

Two individual coaching sessions: This type of coaching session was designed in line with recommendations from the literature (e.g. the process included more than one coaching session, feedback was provided both verbally and in writing and included collaborative goal setting and action planning) [20]. BCTs used with this mode of delivery included, feedback, goal setting, problem solving, and prompts and cues. These sessions were designed to target the TDF domains such as skills, beliefs about capabilities and behavioural regulation. Each session was scheduled to last one hour and was led by the same registered Psychologist who facilitated the education meeting. Additional tools used to support the coaching process were:

-

a.

Audio recordings were collected by the physiotherapists at their consultations with selected chronic LBP patients for assessment and feedback. Directly after a physiotherapist-patient consultation, the audio recording was collected by a research assistant (MH) and submitted to the coach (JM) for review. The results of the review were used to inform the focus of the subsequent coaching session with the physiotherapist.

-

b.

Self-monitoring and reflection sheets were completed by each physiotherapist after each audio recorded consultation during the intervention phase. The sheet asked physiotherapists to record and reflect on their use of SDT-based communication strategies during their patient consultations (e.g. what they felt they did or did not do well?). These sheets were reviewed by the coach along with the audio recordings and informed the feedback provided by the coach during the subsequent session.

-

c.

Goal setting and action planning occurred at the end of each coaching session followed by an email from the coach to the physiotherapist within 24 h with a brief re-cap of the key points of the session and a copy of the agreed updated goal(s) and action sheet for the physiotherapist to refer to.

-

a.

Phase 2 - refinement of the KEDS intervention

A pilot test of the protocol to implement KEDS was undertaken with two physiotherapists at two separate primary care sites to explore face validity, feasibility of intervention delivery as well as to collect preliminary objective data on change in provider communication behaviour. Face validity and feasibility were assessed via semi-structured interviews with participating physiotherapists. Specifically, we were interested in determining if participants perceived that the KEDs intervention addressed key barriers and enablers to using communication strategies in practice in order to make refinements to the intervention components. Additionally, we assessed if participants found the KEDs intervention “acceptable”. Acceptability of the intervention was defined as the perception of the participants that the intervention is agreeable, credible and has relative advantage compared with current treatment practices [32]. It is suggested that if an intervention is acceptable it increases the likelihood of it being adopted in practice [33]. Both interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and reviewed by two members of the research team.

Preliminary data on physiotherapist communication behaviour change was also collected using the Health Care Climate Questionnaire (HCCQ) [34]. The HCCQ assesses the level of autonomy support provided by a health care practitioner to the patient through their communication behaviour. It has good reliability and validity in similar populations [34]. The 6-item version of the HCCQ was used in the present study and includes statements such as “the physiotherapist conveyed confidence in the participant’s ability to make changes”. These statements were assessed on a seven-point Likert scales anchored in 1 = not true at all, 4 = somewhat true and 7 = very true [34]. The scores are averaged for a total scale ranging from 1 to 7.

Results and Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop an implementation intervention that could be used to promote physiotherapist behaviour change in primary care. Specifically, the intervention was developed to support physiotherapist’s enhanced use of theory-informed, evidence-based communication skills in clinical practice. Our development approach was systematic and allowed us to choose behaviour change techniques and delivery modes informed by theory and evidence that addressed some of the specific barriers and enablers identified by key stakeholders in the local context. The subsequent pilot-study with two physiotherapists, allowed us to consider how this intervention could be optimized, tailored and refined prior to a more detailed testing of effectiveness.

Refinements

During the pilot-testing we found that, on the whole, both physiotherapists were positive regarding the success of the KEDS intervention in addressing the barriers of knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities and behavioural regulation; particularly, the coaching process in general and specifically the goal and action sheets and audio-recording review. For example, one physiotherapist noted in the follow-up interviews that “the one on one coaching was fantastic and I think really helped to cement all the learnings”. However, they felt the barrier of limited social support was not addressed effectively through the chosen intervention components; primarily due to wider environmental constraints, of working in isolation with few opportunities to discuss, support and encourage their peers. This is illustrated by the following physiotherapist comment, “we wouldn’t really be sharing our work practices as such, I don’t think I would have the opportunity to sit down with them (i.e. colleagues) and ask them about their experience with the communication skills”. Lastly, in terms of acceptability, both physiotherapists considered the intervention to be relevant and, beneficial to their practice and signalled a desire to continue using these skills in their daily interactions with patients. For example, one of the physiotherapists stated, “I would see myself going forward and using it (i.e. autonomy supportive communication style) the overall benefit to me is the sense of being in partnership with the patient”. Thus, as a result of these initial findings, we intend to use most of the selected strategies but would recommend enhancing the continuing education meeting to further address social support.

In addition, preliminary assessment of physiotherapist behaviour change with the HCCQ revealed an important finding. As part of promoting autonomy supportive behaviour, the KEDs intervention also addresses how to identify and reduce controlling behaviours (e.g. contingent reward or conditional acceptance) which has been negatively associated with long-term behaviour change [35]. Feedback from the semi-structured interviews reinforced the discussion and recognition of controlling behaviours as a useful part of the intervention. Unfortunately, the HCCQ only measures autonomy supportive behaviours. Therefore, based on this finding and in line with recent health related research [36], we would refine the intervention assessment to include measures of autonomy supportive and controlling behaviours to fully assess change in physiotherapist communication behaviour.

Strengths

The MRC guidelines for design and evaluation of complex (e.g. behaviour change) interventions, recommend that researchers fully describe the rationale underpinning the development process and map intervention components to theory and outcome to allow for meaningful evaluation which we have done using the TDF. Thus, our study differs from many previous implementation interventions which did not rely on theory to design interventions [37] and expands on the limited number of theory-informed, tailored interventions developed using a rigorous methodological approach. Moreover, by tailoring the intervention to address specific TDF barriers/enablers and linking those with specific behaviour change techniques, we ensured a better understanding of how change within the intervention might be achieved [38] and increased the opportunity to change clinical practice.

Recommendations for future research

This intervention only addressed barriers and enablers at the intra and interpersonal levels. For example, at the intrapersonal (physiotherapist) level, feedback from interviews indicated that this intervention was acceptable in enhancing the knowledge, skills and self-confidence of participants. This was likely due to specific components of the intervention that addressed these barriers, such as information provision at the continued education meeting and goal-setting, problem solving and feedback through the coaching process. Whereas, at the interpersonal (therapist-to-therapist) level, it seemed the barrier of lack of social support was not addressed adequately by the intervention components. Specifically, the process of encouragement and support through the continued education meeting did not enable support networks to be created within the primary care sites. Operationally, this intervention could also be further challenged by: (i) organisational barriers related to time and workload and (ii) patient expectations, which were originally identified in focus groups but deemed beyond the scope of this intervention. Indeed, both participants in the semi-structured interviews reported the ongoing negative effect of these barriers.

Consequently, future research should consider strategies to further enhance the intervention to address barriers beyond those at the physiotherapist level [39]. For example, participants in the focus groups highlighted the challenges of working with patients who expected passive rather than proactive treatment. This could perhaps be addressed by additional communication with referring primary care GPs about the scope of physiotherapy in chronic pain management as well as eliciting patient expectations and then managing them more effectively using a range of communication modes (e.g. introductory information advising patients what physiotherapy is and what they can expect prior to attending a consultation, this could be provided via postal, telephone or online methods).

Lastly, while we found that individualized coaching was acceptable and likely to provide a positive impact on behaviour; a one-to-one in person approach is costly and perhaps impedes opportunities for wider dissemination. Thus, exploration of providing this component in other formats and at different levels tailored to the individual could also be considered [40]. For example, the use of educational technology such as the virtual environment of Second Life [41] might be an alternative method for training HCPs and improving self-efficacy for the behaviour along with skill development. Additionally, the use of intermediaries such as, local opinion leaders [42] could be an alternative for targeting barriers related to professional role and identify and social influence. Both avenues may be promising and pragmatic ways to support clinician behaviour change.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study applied a systematic and rigorous process to the development of an intervention to support the implementation of an autonomy supportive communication style in primary care physiotherapy. This process ensured that the intervention was theory-informed and evidence-based. Preliminary findings suggested that the intervention was both feasible and acceptable to recipients. These findings also support previous recommendations to adopt a multi-component approach and to consider context specific issues when implementing evidence based guidelines into clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- CPG:

-

Current clinical practice guidelines

- HCPs:

-

Health care professionals

- SDT:

-

Self-determination theory

- KEDS:

-

Knowledge exchange and delivery support

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- CONNECT:

-

Communication style and exercise compliance in physiotherapy

- TDF:

-

Theoretical domains framework

- BCT:

-

Behaviour change techniques

- HCCQ:

-

Health care climate questionnaire

References

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:968–74.

Health IoP. Musculoskeletal briefing. Institute of Public Health Ireland. 2012. http://www.publichealth.ie/sites/default/files/documents/files/MSC%20Briefing%2004%20Sept%202012.pdf. Accessed 2 Aug 2014.

Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:492–504.

Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin C-WC, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–94.

Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F, Capra F, Guccione A, Mugnai R, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:176–85.

Coleman MT, Newton KS. Supporting self-management in patients with chronic illness. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1503–10.

Kennedy A, Rogers A, Bower P. Support for self-care for patients with chronic disease. BMJ. 2007;335:968–70.

Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, et al. Self-Determination Theory Applied to Health Contexts: A Meta-Analysis. Perspect on Psychol Sci. 2012;7:325–40.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester NY: The University of Rochester Press; 2002.

Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol. 1998;17:269–76.

Fortier MS, Sweet SN, O’Sullivan TL, Williams GC. A self-determination process model of physical activity adoption in the context of a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Sport Exercise. 2007;8:741–57.

Williams GC, McGregor HA, Sharp D, Levesque C, Kouides RW, Ryan RM, et al. Testing a self-determination theory intervention for motivating tobacco cessation: Supporting autonomy and competence in a clinical trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25:91–101.

Halvari AE, Halvari H, Bjørnebekk G, Deci EL. Oral health and dental well-being: testing a self-determination theory model. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;43:275–92.

Lonsdale C, Hall A, Williams G, McDonough S, Ntoumanis N, Murray A, et al. Communication style and exercise compliance in physiotherapy (CONNECT). A cluster randomized controlled trial to test a theory-based intervention to increase chronic low back pain patients’ adherence to physiotherapists’ recommendations: study rationale, design, and methods. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:104.

Murray A, Hall AM, Williams GC, McDonough SM, Ntoumanis N, Taylor IM, et al. Effect of a Self-Determination Theory–Based Communication Skills Training Program on Physiotherapists’ Psychological Support for Their Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:809–16.

Forsetlund L, BA, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf FM, Davis D, Odgaard-Jensen J, Oxman AD: Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, 2:CD003030.

O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, Forsetlund L, Bainbridge D, Freemantle N, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Harvey EL. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007, 4:CD000409.

Flodgren G, Parmelli E, Doumit G, Gattellari M, O’Brien MA, Grimshaw J, Eccles MP. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011, 8:CD000125.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O’Brien MA, JohansenM, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD: Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, 6:CD000259.

Baker PRA, Francis DP, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Armstrong R. Managing the production of a Cochrane systematic review. J Pub Health. 2010;32:448–50.

Iles R, Davidson M. Evidence based practice: a survey of physiotherapists’ current practice. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11:93–103.

Hannes K, Staes F, Goedhuys J, Aertgeerts B. Obstacles to the implementation of evidence-based physiotherapy in practice: A focus group-based study in Belgium (Flanders). Physiother Pract Res. 2009;25:476–88.

Salbach NM, Jaglal SB, Korner-Bitensky N, Rappolt S, Davis D. Practitioner and Organizational Barriers to Evidence-based Practice of Physical Therapists for People With Stroke. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1284–303.

Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care. 2001;39:46–54.

French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:38.

Cane JE, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

French SD, McKenzie JE, O'Connor DA, Grimshaw JM, Mortimer D, Francis JJ, et al. Evaluation of a Theory-Informed Implementation Intervention for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain in General Medical Practice: The IMPLEMENT Cluster Randomised Trial. PLoS One. 2013;8.

Bussières AE, Al Zoubi F, Quon JA, Ahmed S, Thomas A, Stuber K, et al. Fast tracking the design of theory-based KT interventions through a consensus process. Implement Sci. 2015;10:18.

Porcheret M, Main C, Croft P, McKinley R, Hassell A, Dziedzic K. Development of a behaviour change intervention: a case study on the practical application of theory. Implement Sci. 2014;9:42.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From Theory to Intervention: Mapping Theoretically Derived Behavioural Determinants to Behaviour Change Techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:660–80.

Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2013;347:f6753.

Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182:E839–42.

Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate glucose control in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1644–51.

Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C. Autonomy support and control in weight management: What important others do and say matters. Brit J Health Psychol. 2014;19:540–52.

Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Stott K, Hindle L. Predicting psychological needs and well-being of individuals engaging in weight management: The role of important others. Appl Psychol Health and Well-being. 2013;5:291–310.

Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5:14.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behaviour change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Bernhardsson S, Larsson ME, Eggertsen R, Olsen MF, Johansson K, Nilsen P, et al. Evaluation of a tailored, multi-component intervention for implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in primary care physical therapy: a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:105.

Ivers NM, Sales A, Colquhoun A, Michie S, Foy R, Francis JJ, et al. No more ‘business as usual’ with audit and feedback interventions: towards an agenda for a reinvigorated intervention. Implement Sci. 2014;9:14.

Mitchell S, Heyden R, Heyden N, Schroy P, Andrew S, Sadikova E, et al. A Pilot Study of Motivational Interviewing Training in a Virtual World. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e77.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Health Research Board for a Health Research Award (HRA_POR/2010/102/k) that funded this project and the physiotherapists’ and patients’ who agreed to participate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Authors DAH, CL and AMH were involved in the conception of the research question and study aim. Authors JM, DAH, CL, AMH, MH, AM and SG were involved in the study design. Authors JM, DAH, MH, AM, JT, BJ, IT and SG were involved in pilot-testing the study protocol. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the pilot-test findings and reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Matthews, J., Hall, A.M., Hernon, M. et al. A brief report on the development of a theoretically-grounded intervention to promote patient autonomy and self-management of physiotherapy patients: face validity and feasibility of implementation. BMC Health Serv Res 15, 260 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0921-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0921-1