Abstract

Background

An increasing number of studies have documented the effectiveness on various types of face-to-face and online mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in reducing anxiety among general population, but there is a scarcity of systematic reviews evaluating evidence of online MBIs on anxiety in adults. Therefore, we examined the effects of online mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on anxiety symptoms in adults and explored the moderating effects of participant, methods, and intervention characteristics.

Methods

We systematically searched nine databases through May 2022 without date restrictions. Inclusion criteria were primary studies evaluating online mindfulness-based interventions with adults with anxiety measured as an outcome, a comparison group, and written in English. We used random-effects model to compute effect sizes (ESs) using Hedges’ g, a forest plot, and Q and I2 statistics as measures of heterogeneity; we also examined moderator analyses.

Results

Twenty-six primary studies included 3,246 participants (39.9 ± 12.9 years old). Overall, online mindfulness-based interventions showed significantly improved anxiety (g = 0.35, 95%CI 0.09, 0.62, I2 = 92%) compared to controls. With regards to moderators, researchers reported higher attrition, they reported less beneficial effects on anxiety symptoms (β=-0.001, Qmodel=4.59, p = .032). No other quality indicators moderated the effects of online mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety.

Conclusion

Online mindfulness-based interventions improved anxiety symptoms in adult population. Thus, it might be used as adjunctive or alternative complementary treatment for adults. However, our findings must be interpreted with caution due to the low and unclear power of the sample in primary studies; hence, high-quality studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are a common mental health problem [1,2,3]. Anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive worry that is difficult to control and can be accompanied by physical symptoms including restlessness, being easily fatigued, difficulty concentrating, irritability, or sleep disturbances [2, 4]. Women were more likely to experience mild, moderate, or severe symptoms of anxiety than men [1, 5].

The prevalence of anxiety has increased worldwide. Globally, 45.8 million incident cases of anxiety disorders, 301.4 million prevalent cases and 28.7 million DALYs were estimated in 2019 [3]. Examples, in each country, over 12% of Thai adults have anxiety symptoms [6, 7]. In the United Kingdom (UK), the incidence of anxiety symptoms in young adults rose from 6.2/1000 person-years at risk (PYAK) in 2003 to 15.3/1000 PYAR in 2018 [8]. Terlizzi and Villarro [5] found that around 15% of adults in the United States experienced symptoms of anxiety. In China, approximately 35% of adults experienced with anxiety symptoms [9, 10].

Anxiety disorders can have wide-ranging negative effects on adults’ functioning. They are associated with lower cognitive performance [11] and sleep disturbance [12], and a high risk of somatic illness such as pain or fatigue [13]. Additionally, anxiety is related to chronic disease such as GI diseases [14, 15] and heart disease [13]. Moreover, having anxiety disorder was associated with a low quality of life [16], and a lot of limitation in daily living such as social restriction [17]. Importantly, not only anxiety disorder associated with individuals functioning but also impact to economic burden [18,19,20]. Anxiety disorder was associated with considerable economic costs owing to lost work productivity and high medical resource use [20, 21]. As a systematic review and meta-analysis by Konnopka and König [22] found that an average of direct cost of anxiety disorder corresponded to 2.08% of health care costs and 0.22% of gross domestic product (GDP), whereas indirect cost, on average, corresponded to 0.23% of GDP.

Pharmacologic treatments for anxiety, such as anxiolytics and anti-depressants, have been effective for helping control symptoms of anxiety in adults, but many are not recommended for long-term use. For instance, benzodiazepine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the drugs of choice for the treatment of anxiety. However, chronic use of benzodiazepine can lead to addiction, and abrupt discontinuation of treatment can lead to withdrawal syndrome [23, 24]. The chronic use of SSRIs can produce side effects such as nervousness, tremors, sweating, nausea, diarrhea, and difficulty falling asleep or frequent awakening [25].

Non-pharmacologic treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have been used to treat symptoms of anxiety, but once CBT is discontinued, many patients with anxiety become unresponsive or continue to have residual symptoms [26]. Additionally, there are several barriers to CBT delivery, such as insufficient therapists [27]; stigmatization; long waiting times for treatment; and high costs [28, 29]. Thus, alternative and complementary therapies to improve anxiety symptoms are growing. One of these therapies is mindfulness-based intervention (MBIs).

Mindfulness, is a process that leads to a mental state defined by nonjudgmental awareness of one’s experiences, thoughts, physiological states, consciousness, and environment, while fostering openness, curiosity, and acceptance [30, 31]. Thus, mindfulness-based intervention (MBIs) is a practice that allows for self-regulation of the body and mind through body scan, sitting meditation and mindfulness movement such as yoga or other mindfulness exercise [31]. Notable, mindfulness training is recognized as cognitive training because individuals are encouraged to understand the relationship between their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors related anxiety. With this practice, individuals become more aware and can self-regulate their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors related to anxiety [32]. Mindfulness principles are applied to help individuals in identifying an alternative in mood without immediately evaluating or responding to it. This increased internal awareness is then combined with cognitive therapy techniques which teach individuals to disengage from maladaptive patterns of repetitive thoughts that are associated with anxiety symptoms [30]. Researchers have shown that using MBIs to treat adults with symptoms of anxiety has fewer barries when compared to other non-pharmacologic treatments and is cost effective [33]. MBIs refer to a range of therapeutic approaches that guide individuals to use mindfulness techniques, including formal and informal exercises [31, 34], and emphasizes a non-judgmental focus on and awareness of the present moment [31]. Formal exercises that facilitate mindfulness include sitting meditation, mindful movement, and body scanning. Informal exercises include mindful eating and are designed to promote mindful awareness in daily activities [34, 35]. Traditionally, MBIs included a range of formal, daily home-based mindfulness practices informed by mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR); mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT); and adapted mindfulness-based interventions (adapted MBIs). With adapted MBIs, researchers adapted structured sessions of mindfulness-based interventions to be shorter than MBSR and MBCT.

Researchers have conducted meta-analyses on various types of face-to-face and online MBIs to improve anxiety symptoms in the specific population [36,37,38,39]. For instance, Lin, Lin [40] found that MBIs significantly improved anxiety in cancer patients (SMD=-3.48, 95%CI-4.07, -2.88, s = 10). Similarly, Li, Sun [41] found MBIs could significantly improve anxiety in nursing students (SMD=-0.45, 95%CI, − 0.73, − 0.17, p = .001). In addition, Spijkerman and Bohlmeijer [42] found that online MBIs had a small effect on anxiety (SMD = 0.22, 95%CI.05, 0.39, s = 10). Moreover, Witarto et al. [43] found that online MBIs could improve the severity level of anxiety in adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (g=-0.25, 95%CI, − 0.43, 0.06, p = .008, s = 8). Furthermore, Gong et al. [44] found that online MBIs had a positive impact to reduce anxiety symptoms in university students (SMD=-0.34, 95%CI, − 0.57, − 0.11, p = .004, s = 6). However, all research teams [41,42,43,44] included a small number of primary studies (s = 5–10), did not specifically included in general adults [40, 44] and did not examine the subgroup analysis to explore the source of heterogeneity [40, 41]. Conducting meta-analysis with a small number of primary studies may overestimate the effect sizes [45, 46].

Importantly, no prior researchers specifically conducted meta-analyses that address the effects of online MBIs on anxiety symptoms and explore the subgroup analysis in the general adult population. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effects of online MBIs on anxiety symptoms in adult populations. We also explored the moderator effects of source, participants, methods, and intervention characteristics. We hypothesized that adults with anxiety who engaged in online MBIs would have fewer anxiety symptoms than adults who did not engage in online MBIs.

Methods

Design

The Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) framework guided this study by assisting in the identification, selection, and critical appraisal of the literature [47]. A study protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (CRD 42,022,312,239).

Search strategy and selection criteria

A total of nine electronic databases (i.e., CINAHL with full text, PsycINFO, Ovid Medline, PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, ProQuest & Theses, Mindfulness Journal, and ScienceDirect) were searched using key terms to capture mobile health or digital interventions, anxiety, and mindfulness-based interventions among adults to retrieve all relevant articles from 2014 to 2022 (See Supplementary Table 1). Subject headings were used in databases when appropriate. The title and abstract of each article were determined independently by the research team for all of the identified articles. Conflicts were resolved by consensus with the senior researcher. Reference lists of the included articles, reviews, and meta-analysis were inspected for additional articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following criteria were used to select relevant studies for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analyses: (1) studies that included adults with anxiety; (2) studies that used an experimental design (RCT, quasi); (3) the treatment group received MBIs including MBSR, MBCT, and adapted MBIs either with or without guided meditation; (4) the MBIs were administered via the internet or a computer application including virtual classrooms; (5) the control group received a usual (TAU) control group, waitlist control group; (6) the treatment outcome was quantitative anxiety; and (7) studies were written in English. The exclusion criteria were: (1) interventions were just a psychoeducation program and did not involve mind-body exercises for enhancing mindfulness; (2) studies in which the researchers combined MBIs and other forms of therapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, supportive therapy, antidepressant treatment, or therapies such as yoga, tai-chi, transcendental meditation, acceptance and commitment therapy), making it difficult to distinguish the effects of online MBIs from other therapies because we were specifically interested in the effect of online MBIs on anxiety.

Study selection and eligibility

Three of the authors (CR, KM, SO) independently assessed the eligibility of all studies that examined the effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety, based on the selection criteria. Studies involving other groups of participants, such as adolescents and older adults, were excluded. Disagreements between evaluators were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and coding

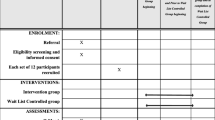

A codebook was developed based on the previous studies [48, 49] to extract data from the eligible studies and revised it during pilot testing with three primary studies. These included five categories [48, 49], which were: source of information, methods, interventions, participants, and outcomes. Source of information included the eligibility criteria and the author, year, funding, country, and publication status. Methods variables included setting, type of comparison group, sampling, and quality indicators such as group assignment, concealed allocation, data collectors masking, intention to treat, fidelity check, power estimation, and group comparison [50]. Interventions variables included the type (MBSR, MBCT, adapted MBIs); format (i.e., mobile application, website-based intervention); whether the intervention was guided, body scan, psychoeducation, group discussion, sitting meditation, or body movement; and whether there was counseling and home assignments. We also extracted days across the intervention, number of weeks in which the intervention was administered, number of intervention sessions, and minutes per session. Participants variables included the total number of participants, their mean age and standard deviation, participants in the intervention group, participants in the control group, number of participants at analysis in both groups, number of dropouts, number of females, number of participants across races, and presence of mood disorders, stress, learning disorders, and the use of drugs. Finally, the outcome variables included anxiety instruments, reliability of scale, mean and standardized anxiety scores, and the effect direction [48, 49].

Data was extracted by two of the authors (PT & JT). Any inconsistencies in data extraction were resolved via discussion between the research team (PT, KM, JT, & SO) and through consultation with the third researcher (CR).

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS to conduct descriptive statistics for the study characteristics. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) was used to compute the effect size (ES) by using the standard mean differences between online MBIs and comparison groups’ posttest anxiety scores [46]. Because the included studies differ in ways that cannot be measured such as intervention delivery, setting features, and more, we assumed that the included studies had different underlying true effect sizes. Therefore, the random-effects model was used because we assumed that the true effect sizes were normally distributed [46]. We also used Hedge’s with 95% confidence interval (CIs) to estimate the ES because it can correct the bias from small study samples [46].

Heterogeneity assessment

To test the heterogeneity across studies, we used the forest plot, which visually demonstrates the degree to which data from multiple studies overlap with one another. Also, Q statistic was used for exploring the total dispersion; significance indicates heterogeneity [46]. Additionally, we used the I2 statistic, which is the ratio of effect size variability to total variability indicating the observed study effect sizes are more different from each other than what we would expected due to chance alone [46]. The I2 statistic reflects the proportion of variance that is true. A value of 25%, 50%, and 75% reflect low, moderate, and high variability [46].

Finally, we examined the subgroup analyses based on the source of information, participants, method, and intervention characteristics to explore the source of heterogeneity [46, 51]. We used a meta-analytic analog of ANOVA for categorical moderators and meta-regression, an analog of regression analysis for continuous moderators [46, 51].

Assessment of methodological quality

To assess the methodological quality of primary studies, we used the quality indicators [48, 49] as moderators and examined the difference in effect sizes for studies with and without the quality indicators [46]. For this meta-analysis, quality indicators of methodological strength included concealed allocation, random assignment, data collector blinded, a priori power analysis, power analysis completed, comparison of demographic groups, and intention-to-treat analysis [46]. These indicators were analyzed as dichotomous moderators, while attrition was analyzed as a continuous moderator [46, 48, 49].

Risk of publication bias

To estimate the publication bias, we used the funnel plot, Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test, and Egger’s bias value [46, 51]. A visually symmetrical funnel-shaped distribution represents the absence of publication bias. The Begg and Mazumdar test computes the rank order correlation (Kendall’s τ) between the standard treatment effect and the variance (standard error, which is primarily affected by the sample size). Significant results suggest that publication bias exists. Similarly, a significant result from the Egger regression test suggests publication bias [46].

Results

Demographics of the study

Initial database searches resulted in 4,846 studies in June 2021, and updated search results added 1,847 studies in May 2022. After 1,860 duplicates were removed, 4,833 remained. We found 17 studies through hand ancestry searches. During the review of title and abstract, an additional 4,783 were excluded because they did not include online MBIs and/or any number of inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 67, 41 primary studies were excluded; 19 were narrative/systematic review/meta-analysis; 16 were qualitative studies, and six studies were research protocol without results. Finally, 26 primary studies (S = 26) met inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (See Fig. 1).

The 26 primary studies that met inclusion criteria provided 32 between-group comparisons (K = 32) because some studies had three comparison groups. For example, researchers included three groups, such as the full mindfulness virtual community program (F-MVC); partial MVC; and waitlist control group [52]. We compared groups that were similar except for the online MBI. All 26 primary studies had been published between 2014 and 2022. A total of 3,246 participants were included across the 26 primary studies; 1,979 participants practiced in the online MBIs, and 1,567 participants served as controls. Five of the 26 primary studies were conducted in the United States of America [53,54,55,56,57] as well as five in the United Kingdom [58,59,60,61,62]; three each in Canada [52, 63, 64], Italy [65,66,67], and China [68,69,70]; and one each in New Zealand [71], Australia [72], Spain [73], Germany [74], Malaysia [75], Denmark [76], and Japan [77] (See Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Participants’ mean ages ranged from 20.1 to 63.1 years (See Table 1). Nine instruments were used to determine anxiety in adults including Generalized Anxiety Assessment, GAD-7 (s = 8); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS (s = 7); The Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI (s = 3); Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, DASS-Anxiety (s = 3); the Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ (s = 1); the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, STAI (s = 2); the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System, PROMIS-anxiety (s = 1); and the Brief Symptoms Inventory, BSI-18 (s = 1). Higher scores reflect higher levels of anxiety symptoms (See Table 1) for intervention descriptions including total weeks of interventions, number of sessions/week, and duration of sessions in minutes/session.

Effects of online mindfulness-based interventions

Overall, the summary effect size across the 32 comparisons was g = 0.35 (95%CI = 0.09, 0.62, p = .009, I2 = 92%), indicating that online MBIs had a moderate effect in reducing anxiety symptoms among adults. Of all 32 comparisons, fifteen comparisons had significant positive effects improvement (See Fig. 2).

The online MBIs group’s pre-post comparisons demonstrated significant reduction in anxiety symptoms with an effect size of g = 0.71 (p < .001) for correlated groups (r = .8) and g = 0.67 (p < .001) for uncorrelated groups. The control group’s pre-post effect sizes showed no improvement in anxiety symptoms for the uncorrelated group (g = 0.15, r = .0) and improvement of anxiety for the correlated group (g = 0.21, r = .8) (See Table 2).

Subgroup analyses

Significant heterogeneity existed across the studies (I2 = 92%, Q = 391.1, p < .001), indicating that the moderator analysis was warranted. Only one variable had a significant moderator (See Tables 3 and 4) depicting the subgroup analyses. When researchers reported higher attrition, they reported lower reduction in anxiety symptoms (β=-0.001, Qmodel=4.59, p = .032). No other quality indicator affected the ES of study.

Publication Bias

The funnel plot appeared asymmetrical (See Fig. 3). Egger’s test of the intercept was 0.975 and non-significant (95%CI, -2.16, 4.12, t = 0.63, df = 30, p = .265); Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test indicated a non-significant Kendall’s tau of 0.01 (p = .454), suggesting publication bias was unlikely. However, the power of the tests is low due to a small number of comparisons (K = 32). Thus, the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Quality of the included studies

After assessing the quality of studies, we revealed that 22 RCTs examined the effectiveness of online MBIs on anxiety in adults. Twenty primary studies provided information on allocation concealment, 17 studies described blinding of outcome assessment, 8 trials addressed the power of sample, and only 1 study reported the fidelity of intervention. Supplemental Table 2 presents the quality of each included study.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis exclusively evaluating the effectiveness of online MBIs on anxiety symptoms in adults. Overall, MBIs have a moderate effect (g = 0.35) on anxiety symptoms in adults compared to control groups. One possible reason might be that with mindfulness practicing, individual pays more attention at the present moment without judgement [32]. Then, an individual learns how to manage their ruminative thoughts/wondering mind related anxiety [32]. Our finding is different from a previous published meta-analysis [42] assessing the effect of online MBIs on psychological outcomes. This meta-analysis found that MBI was small effective in reducing anxiety symptoms (SMD = 0.22, 95%CI.05, 0.39) [42]. However, they included a small number of primary studies (s = 10) which might lead to an overestimate of ES [46] and an inaccurate precision of confidence interval for the common effect size in meta-analysis [78]. Also, these results were different from our study because their meta-analysis included Internet-based mindfulness treatment (s = 1), MBSR (s = 2), MBCT (s = 2) and ACT (s = 5). In our study, we only included MBSR, MBCT and adapted MBIs, which are operationalized the mindfulness based on the philosophical perspective of Buddhist teaching using formal meditation as the main interventional component [79]. We did not include ACT because it relies on the Relational Frame Theory, which is derived from a functional contextualism philosophical perspective and focuses on the behavior of individuals within their historical and situational context [79, 80]. Therefore, our meta-analysis is novel in that it provides a comprehensive examination of the effect of online MBI on anxiety in adults with a greater number of primary studies (s = 26) than the prior meta-analysis (s = 10, [42]. In addition, we conducted moderator analyses, which provide future research directions.

Although gender difference might be a related factor of anxiety disorder [81, 82], most primary research teams were not report the number of participants in each gender result to a limiting for subgroup analysis to explore how gender affects to the ES. Thus, we recommend the primary researchers address the number of participants based on gender.

Attrition rate is considered a factor affecting the online MBIs’ effect. We found that when the attrition rate increased, the effects of online MBIs was reduced, indicating an increase in anxiety scores. Since a higher attrition also results in a smaller number of participants in the analysis, the precision of the effect size is reduced [46, 83, 84]. We recommend that future researchers account for attrition during recruitment of participants.

Strengths and limitations

Ours was the first systematic review and meta-analysis of online MBIs on anxiety symptoms in adults. We did a moderator analysis on the biggest number of primary studies (s = 26) to date. Yet, there are certain drawbacks to this meta-analysis. Initially, we limited our search to main research written in English; relevant studies written in other languages would have been missed. Researchers in the future should incorporate papers published in different languages. Second, due to insufficient data reporting, we did not investigate the impact of several key parameters on the effect magnitude. For example, most researchers did not consider intervention fidelity, which was a constraint for investigating this characteristic that influences effect magnitude. Lastly, most investigations examined outcomes shortly after the intervention was completed (s = 19); long term effects were not measured. Thus, more long-term MBIs studies on anxiety symptoms in adults are needed.

Implications and recommendations

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides evidence for the use of online MBIs in adults with anxiety. Specifically, nurses and health professionals might consider using online MBIs as an adjunctive or alternative complementary treatment to improve anxiety, especially when there are insufficient mental health professionals. Electronic services such as online MBIs might benefit adults who are concerned about negative perceptions of anxiety treatment. Researchers should explore the long-term effects of online MBIs on anxiety in adults. Finally, researchers should account for attrition during the recruitment of participants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that online MBIs have a moderate effect in decreasing anxiety symptoms in adults. Nurses and mental health professionals may use online MBIs as adjunctive or alternative complementary treatment for managing anxiety symptoms in adults. Also, health providers might engage high-risk adults in online MBIs to prevent anxiety disorders. However, our findings must be interpreted with caution due to the low and unclear power of the sample in primary studies; hence, high-quality studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Scarella TM, Boland RJ, Barsky AJ. Illness anxiety disorder: psychopathology, epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2019;81:398–407.

Romanazzo S, Mansueto G, Cosci F. Anxiety in the medically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:873126.

Yang X, et al. Global, regional and national burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2021;30(e6):1–11.

Abed HA, Abd-Elraouf MSE. Stress, anxiety, depression among medical undergraduate students at Benha university and their socio-demographic correlates. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2022;86:27–32.

Terlizzi EP, Villarro MA. Symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder among adults: United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, 2020. 378.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Relationship between depression, generalized anxiety, and metabolic syndrome among buddhist temples population in Nakhon Pathom-Thailand. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018;12(3):e60829.

Sornsenee P, et al. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among micro, small, and medium enterprise restaurant entrepreneurs due to Thailand’s COVID-19-related restrictions: a cross-sectional study. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2022;15:1157–65.

Archer C, et al. Trends in the recording of anxiety in UK primary care: a multi–method approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57:375–86.

Bai J, Cheng C. Anxiety, depression, chronic pain, and quality of life among older adults in rural China: an observational, cross-sectional, multi-center study. J Commun Health Nurs. 2022;39(3):202–12.

Xu Z, et al. Loneliness, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder among chinese adults during COVID-19: a cross-sectional online survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;16(1):e0259012.

Lukasik KM et al. The relationship of anxiety and stress with working memory performance in a large non-depressed sample. Front Psychol, 2019. 10(4).

Cox RC, Olatunji BO. A systematic review of sleep disturbance in anxiety and related disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;37:104–29.

Norbye AD et al. The association between health anxiety, physical disease and cardiovascular risk factors in the general population – a cross-sectional analysis from the Tromsø study: Tromsø 7. BMC Prim Care, 2022. 23(140).

Jones JD, et al. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety, depression and gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Parkinsonism Relat Disorders. 2021;5:100104.

Söderquist F, et al. A cross-sectional study of gastrointestinal symptoms, depressive symptoms and trait anxiety in young adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:535.

Armbrecht E, et al. Economic and humanistic burden associated with depression and anxiety among adults with non-communicable chronic diseases (NCCDs) in the United States. J Multidisciplinary Healthc. 2021;14:887–96.

Norton J, et al. Anxiety symptoms and disorder predict activity limitations in the elderly. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):276–85.

Chodavadia P et al. Prevalence and economic burden of depression and anxiety symptoms among singaporean adults: results from a 2022 web panel. BMC Psychiatry, 2023. 23(104).

Stiles JA, et al. The cost-effectiveness of stepped care for the treatment of anxiety disorders in adults: a model-based economic analysis for the australian setting. J Psychosom Res. 2019;125:109812.

Chodavadia P, et al. Prevalence and economic burden of depression and anxiety symptoms among singaporean adults: results from a 2022 web panel. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(104):1–9.

Hoffman DL, Dukes EM, Wittchen HU. Human and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(1):72–90.

Konnopka A, König H. Economic burden of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38:25–37.

Guedes JM et al. Anxiolytic-like Effect in Adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio) through GABAergic System and Molecular Docking Study of Chalcone (E)-1-(2-hydroxy-3,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-3(4-methoxyphenyl)prop i>-2-en-1-one. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2023. 13(1)

Peng L, Kenneth Mb, Morford L, Levander XA. Benzodiazepines and related sedatives. Med Clin North Am. 2022;106:113–29.

Anagha K, et al. Side effect profiles of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a cross-sectional study in a naturalistic setting. Volume 23. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders; 2021. 4.

Li J, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy for people with anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of random controlled trials. Annals of Palliative Medicine. 2021;10(7):7596–612.

Olthuis JV, et al. Therapist-supported internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; 2016. p. 3.

Hedman E, et al. Cost effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy and behavioural stress management for severe health anxiety. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e00932.

Salza A, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) anxiety management and reasoning bias modification in young adults with anxiety disorders: a real-world study of a therapist-assisted computerized (TACCBT) program Vs. “person-to-person” group CBT. Internet Interventions. 2020;19:100305.

Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):739–49.

Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10(2):144–55.

Rodrigues MF, Nardi AE, Levitan M. Mindfulness in mood and anxiety disorders: a review of the literature. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017;39(3):207–15.

Liu X et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res, 2021. 300.

Segal Z, Williams JM, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002.

Segal ZV, Walsh KM. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms and relapse prophylaxis. Curr Opinoin Psychiatry. 2016;29:7–12.

Kang MJ, Myung SK. Effects of Mindfulness-Based interventions on Mental Health in Nurses: a Meta-analysis of Randomized controlled trials. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2022;43(1):51–9.

Zhang Y, et al. Effect of mindfulness on psychological distress and well-being of children and adolescents: a Meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2022;13(2):285–300.

Zhu L et al. Mind–body exercises for PTSD symptoms, Depression, and anxiety in patients with PTSD: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Psychol, 2022. 12.

Zhou X et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on anxiety symptoms in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res, 2020. 289.

Lin LY, et al. Effects of Mindfulness-Based therapy for Cancer Patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings; 2022.

Li YF, et al. Effects of mindfulness meditation on anxiety, depression, stress, and mindfulness in nursing students: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Nurs. 2020;7(1):59–69.

Spijkerman MPJ, Bohlmeijer ET. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: a review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:102–14.

Witarto BS, et al. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0274177.

Gong XG, et al. Effects of online mindfulness-based interventions on the mental health of university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1073647.

Zhang Z, Xu X, Ni H. Small studies may overestimate the effect sizes in critical care meta-analyses: a metaepidemiological study. Crit Care. 2013;17:1–9.

Borenstein M, et al. Introduction to meta-analysis. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2021.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Reangsing C, Rittiwong T, Schneider JK. Effects of mindfulness meditation interventions on depression in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging and Mental Health, 2020: p. 1–11.

Reangsing C, Punsuwun S, Schneider JK. Effects of mindfulness interventions on depressive symptoms in adolescents: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;115:103848.

Conn VS, Rantz MJ. Focus on research methods research methods: managing primary study quality in meta-analyses. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26:322–33.

Borenstein M, et al. Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2009.

Ahmad F, et al. An eight-week, web-based mindfulness virtual community intervention for students’ mental health: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7(2):e15520.

Bosso KB. The effects of mindfulness training on BDNF levels, depression, anxiety, and stress levels of college students. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2020;81(12–B):No–Specified.

Cox CE, et al. Effects of mindfulness training programmes delivered by a self-directed mobile app and by telephone compared with an education programme for survivors of critical illness: a pilot randomised clinical trial. Thorax. 2019;74(1):33–42.

Messer D. Effects of internet training in mindfulness meditation on variables related to cancer recovery. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2018;78(9–BE):No–Specified.

Simonsson O et al. Effects of an eight-week, online mindfulness program on anxiety and depression in university students during COVID-19: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res, 2021. 305.

Westenberg RF, et al. Does a brief mindfulness exercise improve outcomes in upper extremity patients? A randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(4):790–8.

Bogosian A, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a mindfulness intervention delivered via videoconferencing for people with Parkinson’s. J Geriatr Psychiatr Neurol. 2022;35(1):155–67.

Cavanagh K et al. A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention in a non-clinical population: replication and extension. Mindfulness, 2018.

Hearn J. Efficacy of online mindfulness for people with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41(5):605–6.

Krusche A, et al. Mindfulness for pregnancy: a randomised controlled study of online mindfulness during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2018;65:51–7.

Querstret D, Cropley M, Fife-Schaw C. The effects of an online mindfulness intervention on perceived stress, depression and anxiety in a non-clinical sample: a randomised waitlist control trial. Mindfulness. 2018;9(6):1825–36.

El Morr C, et al. Effectiveness of an 8-week web-based mindfulness virtual community intervention for university students on symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7(7):e18595.

Segal ZV, et al. Outcomes of online mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for patients with residual depressive symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(6):563–73.

Bossi F et al. Mindfulness-based online intervention increases well-being and decreases stress after Covid-19 lockdown. Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1).

Cavalera C, et al. Online meditation training for people with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2019;25(4):610–7.

Pagnini F, et al. An online non-meditative mindfulness intervention for people with ALS and their caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degeneration. 2022;23(1–2):116–27.

Liu Y, et al. Using mindfulness to reduce anxiety and depression of patients with fever undergoing screening in an isolation Ward during the COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology; 2021. p. 12.

Yang M, et al. Effects of an online mindfulness intervention focusing on attention monitoring and acceptance in pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2019;64(1):68–77.

Zhang H, et al. A brief online mindfulness-based group intervention for psychological distress among chinese residents during COVID-19: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness. 2021;12:1502–12.

Flett JAM et al. Mobile mindfulness meditation: a randomised controlled trial of the effect of two popular apps on mental health. Mindfulness, 2018.

Kladnitski N et al. Transdiagnostic internet-delivered CBT and mindfulness-based treatment for depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 2020. 20.

Orosa-Duarte Á, et al. Mindfulness-based mobile app reduces anxiety and increases self-compassion in healthcare students: a randomised controlled trial. Med Teach. 2021;43(6):686–93.

Boettcher J, et al. Internet-based mindfulness treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2014;45(2):241–53.

Ghawadra SF, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based training on stress, anxiety, depression and job satisfaction among ward nurses: a randomized control trial. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2020;28(5):1088–97.

Nissen ER, et al. Internet-delivered mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2020;29(1):68–75.

Noguchi R et al. Effects of five-minute internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy and simplified emotion-focused mindfulness on depressive symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 2017. 17(1).

Liu XS. Sample size and the Precision of the confidence interval in Meta-analyses. Therapeutic Innov Regul Sci. 2015;49(4):593–8.

Chiesa A, Malinoski P. Mindfulness-based approaches: are they all the same? J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(4):404–24.

Boone MS, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy, functional contextulaism, and clinical social work. J Hum Behav Social Environ. 2015;25(6):643–56.

Farhane-Medina NZ et al. Factors associated with gender and sex differences in anxiety prevalence and comorbidity: a systematic review. Sci Prog, 2022. 105(4).

Strand N, Fang L, Carlson JM. Sex differences in anxiety: an investigation of the moderating role of sex in performance monitoring and attentional bias to threat in high trait anxious individuals. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:627589.

Meyerowitz-Katz G, et al. Rates of attrition and dropout in app-based interventions for chronic disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Int Res. 2020;22(9):e20283.

Osho O, Owoeye O, Armijo-Olivo S. Adherence and attrition in fall prevention exercise programs for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2018;26:304–26.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All five authors (CR, PT, KM, JT, & SO) were responsible for acquisition, interpretation, and drafting the article. All authors (CR, PT, KM, JT, & SO) substantially contributed to the data extraction, and critically revised the work for important intellectual content. The first (CR), and last author (SO) were included in the identification, selection, data analysis, article drafting, and critically revised the work. All authors (CR, PT, KM, JT, & SO) provided final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspect of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1

. An example of the electronic search strategy. Supplementary Table 2. Quality Indicators of Included Primary Studies (s=26). Supplementary Table 3. Summary Demographic of Included Primary Studies (s=26)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Reangsing, C., Trakooltorwong, P., Maneekunwong, K. et al. Effects of online mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on anxiety symptoms in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther 23, 269 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-023-04102-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-023-04102-9