Abstract

Background

Complementary Medicine (CM) continues to thrive across many countries. Closely related to the continuing popularity of CM has been an increased number of enrolments at CM education institutions across the public and private tertiary sectors. Despite the popularity of CM across the globe and growth in CM education/education providers, to date, there has been no critical review of peer-reviewed research examining CM education undertaken. In direct response to this important gap, this paper reports the first critical review of contemporary literature examining CM education research.

Methods

A review was undertaken of research to identify empirical research papers reporting on CM education published between 2005 and 17. The search was conducted in May 2017 and included the search of PubMed and EBSCO (CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED) for search terms embracing CM and education. Identified studies were evaluated using the STROBE, SRQP and MMAT appraisal tools.

Results

From 9496 identified papers, 18 met the review inclusion criteria (English language, original empirical research data, reporting on the prevalence or nature of the education of CM practitioners), and highlighted four broad issues: CM education provision; the development of educational competencies to develop clinical skills and standards; the application of new educational theory, methods and technology in CM; and future challenges facing CM education. This critical integrative review highlights two key issues of interest and significance for CM educational institutions, CM regulators and researchers, and points to number of significant gaps in this area of research. There is very sporadic coverage of research in CM education. The clear absence of the robust and mature research regarding educational technology and e-learning taking place in medical and or allied health education research is notably absent within CM educational research.

Conclusion

Despite the high levels of CM use in the community, and the thriving nature of CM educational institutions globally, the current evidence evaluating the procedures, effectiveness and outcomes of CM education remains limited on a number of fronts. There is an urgent need to establish a strategic research agenda around this important aspect of health care education with the overarching goal to ensure a well-educated and effective health care workforce.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The practice, uptake and economics of Complementary Medicine (CM) - a range of therapies, products and approaches to health and illness not traditionally associated with the medical profession or medical curriculum [1] - continues to thrive in many countries [2,3,4,5,6,7] and concurrently the enrolments at CM education institutions have steadily increased [8, 9]. CM education institutions providing training and qualifications including naturopathy, nutritional medicine, homeopathy, acupuncture, massage therapy and herbal medicine are located across both the public and private tertiary sector in many regions, Australia [10], USA [11], UK [12], Asia [13]. The professionalization of the CM education sector appears to be evolving with continuing professional education, education standards, levels of foundational medical science and higher levels of qualifications emerging in recent years [14,15,16,17,18].

These education institutions face innumerable challenges. These include preparing CM graduates to function as health professionals in a contemporary health system when they apply predominantly traditional principles and concepts [19, 20]. Another challenge is training students in inter-professional care when the focus during training is often on mastering a traditional technique or philosophy [21]. Further challenges involve providing education about evidence-based healthcare when the focus during training is often on learning and applying traditional evidence - defined here as evidence with a long and coherent history of use, well documented in monographs such as materia medica and other texts, mainly inductive in nature, and passed on orally over many generations [22]. This is pertinent in a field that has 700 Cochrane systematic reviews yet one where traditional evidence and knowledge is also highly regarded. Further, providing education on patient-centred care [23], supporting non-traditional students [24, 25] and also gaining funding for and providing education related to perceived non-credible CM modalities in conventional tertiary education settings are challenges [26]. In addition, challenges continue to arise for education leaders both within and beyond CM regarding technological advances and the consequences for students, educators and institutions [27,28,29]. New developments in healthcare such as e-health/tele-health [30] and a growth in interest in the pedagogy and andragogy of online learning [31, 32] in general, present challenges for educational institutions, professional associations and regulators. Alongside these general educational challenges, faculty resistance to change, the digital divide between students, and between students and faculty, and online readiness for study has been a focus of recent research and discourse in health education [33,34,35,36]. More broadly, beyond CM-specific education, tertiary students are increasingly engaging with technology in both their personal and study lives [37, 38] and technology-based learning and teaching in higher education is becoming almost a presumed proposition in many undergraduate courses [39, 40]. CM education is not exempt from such circumstances and there is a necessity for future research on this topic.

In direct contrast to research related to CM practitioner education, there are numerous studies investigating the degree of, and attitudes to CM in conventional medical training [41,42,43], in biomedical education [44], midwifery [45], pharmacy [46,47,48] and in nursing training [44, 49,50,51,52]. Paradoxically, much of the research regarding CM education relates to its importance and application in nursing education [53], or the experience of integrating naturopathy into nursing educational programs [54], the education of physicians about their patients and CM [55], or addressing the obstacles to success in the implementing of change in science delivery in nursing [56].

The growing CM workforce requires training appropriate to performing evidence-informed, co-ordinated and inter-professional care within the broader health system and developing the evidence-base on this topic will not only aid the CM field but also provide potential insights for health/medical education more broadly [57]. The development of a robust evidence-base on this topic requires a clear understanding of the current landscape. Unfortunately, there has been no critical review of the peer-reviewed research examining CM education to date. In direct response to this important research gap, this paper reports the first critical review of contemporary literature examining a number of key issues across the CM education field.

Methods

Aim

The aim of this critical integrative review [58] was to review all published original research found in peer-reviewed literature examining education within higher educational institutions that provide training for CM professionals.

Method

A database search was undertaken to identify original peer-reviewed literature published from 2005 to 2017 reporting on issues relating to CM education. This date range was chosen to reflect contemporary issues and ensure findings were as pertinent to current practice and policy as possible.

Search strategy

The search was conducted in May 2017 and included the systematic search of PubMed and EBSCO (CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED). MESH terms and keywords from related papers were explored to guide the process of selecting search terms, and the process was further refined after referral to a related 2014 review [59]. The first stage was conducted in PubMed. Search A - The search terms embracing CM included, Complementary Therapies, Complementary Medicine, Homeopathy, Naturopathy, Herbal Medicine, Acupuncture, Acupuncture Therapy, Medicine, Chinese Traditional, Massage, Therapy, Soft Tissue, Integrative Medicine, Medicine, Traditional, Holistic Health, Osteopathic Medicine, Manipulation, Chiropractic, Musculoskeletal Manipulations, Physical Therapy Modalities. Filter 2005–2017. (n = 258,099). Search B - The search terms embracing education included, education, learning, curriculum, teaching, health occupation students, eLearning, E-Learning, online learning, educational technologies, blended learning. Filter 2005–2017. (n = 906,575). A + B Combined (n = 38,441). Stage 2 was conducted in EBSCO. The same search terms used in PubMed when entered into EBSCO provided millions of hits, education (n = 160 + M) hits, Complementary Therapies (n = 629,674) hits and too many potential papers to work. Including ‘eLearning’ and ‘e-learning’ was manageable but these two terms with ‘learning technologies’ made it impossible to proceed. In the process, a review was located which had used similar terms but a different strategy, Milanes 2014 systematic review, Is a blended learning approach effective for learning in allied health clinicians? Because of the enormous number of hits using the EBSCO database, and based on this article a revised search method was undertaken for the EBSCO search. Search C - EBSCO Search terms, 1. Online learning OR blended learning or web-based learning, 2. e-learning OR elearning, 3. education* OR curriculum* OR teaching* OR learn*, 4. Combine all (1–3) with AND 5. Complementary Therapies*, 6. Search 4 AND 5 (n = 637), 7 Limit to articles from 2005 (n = 567 (with duplicates removed)). Search D - This process was completed again searching on the slightly different terminology. Search terms, 1. Online learning OR blended learning or web-based learning, 2. e-learning OR elearning, 3. education* OR curriculum* OR teaching* OR learn*, 4. Combine all (1–3) with AND, 5. Complementary Medicine*, 6. Search 4 AND 5 = 1203, 7. Limit to articles from 2005 = (n = 1013 (with duplicates removed)). Stage 3 (Milanes Refined) PubMed. Search E - The search terms Health occupation students OR educational technologies OR teaching OR curriculum AND complementary therapies, filter to last 10 years. Search results = (n = 8439). Totals: Search C – n = 567, Search D – n = 1013, Search E – n = 8439. Total Papers n = 10,019. Duplicates removed n = 523. Grand Total 9496. Manual searching of reference lists of identified papers was also conducted to ensure as full coverage of literature as possible.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers written in English, presenting original empirical research data, related to courses where graduates receive a qualification in a CM to a standard accepted by those professions and reporting on the prevalence or nature of the education of CM practitioners in some way were included in the review. Papers reporting conference presentations, or studies relating to how pharmacy, nursing or registered medical professionals are educated regarding their patient behaviours or looking to how they accumulate CPD points in short term CM topics were excluded.

Search outcomes

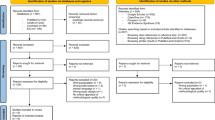

The combined (Complementary Therapies n = 420,476 and Education n = 102,024) search results (n = 9927) were imported into Endnote. Of these, 9895 papers were excluded via title and abstract due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, and all identified duplicates (n = 280) were excluded leaving 32 papers. Upon reviewing full papers an additional 26 articles were excluded due to their focus on just allied health and / or only learning technologies with no CM focus; leaving 6 papers. A total of 12 additional papers were identified for review following manual searches. In total, 18 papers were identified for this review. The process undertaken for this review is presented in Fig. 1.

Critical analysis of included papers

Our critical literature appraisal employed three analytical tools, STROBE [60, 61], SRQR [62] and MMAT [63]. Papers were evaluated for quality and the findings are collated in Table 1.

Results

Of 9927 identified papers, 18 papers met the review inclusion criteria. An overall synopsis of all papers included in the review incorporated preliminary categorical analysis is outlined in Table 2. The identified studies were conducted in Australia (n = 7), the US (n = 5), Norway (n = 2) and one each from Canada, Taiwan, Israel and India. The research designs reported in the reviewed literature varied widely with quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies reported. The quantitative studies selected for review utilized a number of survey design approaches and attracted samples of between 10 and 246 individual participants. The qualitative studies identified employed survey methods [1, 2, 8–14, 18] as well as interviews [1, 6, 11, 15, 16], open essays [2] and focus groups [17]. The spread, focus and identification of themes and topics by CM therapy is represented in Table 2. The naturopathic profession has received most attention from researchers within the international CM education landscape, followed by acupuncture. There are three studies on homeopathy, two studies of chiropractic, and one each of osteopathy, herbal medicine, ayurveda and massage. Six of the included studies focus on a specific class inside of a CM college [1–4, 7, 17], four on academics in CM institutions [6, 12, 16], four studies surveyed members of professional associations [5, 10, 17], and four surveyed College directors [8, 9, 13, 18]. Thematic categorization of the included papers identified four substantive topic areas: (1) CM education provision, (2) the development of educational competencies to develop clinical skills and standards, (3) the application of existing and new educational theory, methods and technology in CM, and (4) future challenges facing CM education.

CM education provision

The review identified three papers that reported a simple description of educational provision in an area of CM. One study compared naturopathy and chiropractic curricular in Australia. Course structures and subject unit descriptions for accredited naturopathic courses were examined from websites where they existed and in some instances short follow-up interviews were conducted. This study reported the percentage of curriculum devoted to medical sciences and clinical training whereby it was found that on average, chiropractic courses allocated 45.9% of their curricula to medical sciences, whereas university-based naturopathy courses allocated 26.2% to medical science and non-university naturopathy courses allocated 23.1% [64]. Another study reported on the scope of education provision in homeopathy and examined the preponderance of accredited full-time and part-time courses and accredited and non-accredited courses in Europe. This cross-sectional survey of 85 homeopathy education providers found an average of 47 enrolled students and 142 graduates in these generally small schools. Course duration lasted on average 3.6 years part-time, less than half had entry requirements, provided any medical science education or required students to obtain medical science tuition elsewhere. Average teaching hours at surveyed schools were 992 overall, with 555 h devoted to didactic homeopathy study, while the rest focused on clinical training [65]. A similar 2009 study focused on the demographics, satisfaction, challenges and expectations of homeopathy students, teachers and school administrators in North America. The study consisted of three separate surveys targeted at homeopathy students, faculty and school directors consisting of 40 questions with a 91.5% completion rate [66]. It was found that there were 29 homeopathy schools, with 250 teachers and 1080 students currently enrolled in the United States. Programs varied considerably in length; however the average program (670 h) was barely sufficient to meet the minimum standards for homeopathic certification. Homeopathy teachers tend to be older than both homeopathy students or practitioners. The average age of students is 54.3 years old. Although the vast majority of students are female (90%) and practitioners are female (75%), males are much more common as teachers (43.5%) and school directors (45%). As with homeopathy students, practitioners, and teachers, homeopathy school directors are nearly all Caucasian (85%). An important conclusion was that education in homeopathy in the United States has largely remained stagnant in the last 10 years. Although many new schools have been formed, many have closed. It was not speculated as to the cause.

The development of educational competencies to develop clinical skills and standards

Eight papers from the review focused on improving education and clinical skills in CM. One study reporting findings from 43 education providers of naturopathy and western herbal medicine in Australia found educational standards varied widely, including unsustainable variations in award types, contact hours, clinical education, length of courses and course content with some practitioners unlikely to be trained to professional standards. This study found a need for better integration of complementary care with mainstream healthcare necessitating education to rise to the level of a bachelor degree [67]. The development or application of learning competencies was a focus of these eight papers. Competencies and competency models refer to how the knowledge, skills, and abilities required by these standards are structured. In a study focussing on the skills, knowledge, attributes and competencies of homeopaths and homeopathy education provision, telephone interviews with 17 educators from different schools in 10 European countries were conducted [68]. This qualitative study used constant/simultaneous comparison and analysis to develop categories and properties of educational needs and theoretical constructs and to describe behaviour and social processes and showed educators define a competent homeopath as a professional able to help patients in the best way possible. It was found that course providers and teachers required the competency to be student-centred, and students and homeopaths to be patient-centred [68]. In an Australian study, CM practitioners were reported as having a low level of confidence in identifying clients requiring referral to registered health practitioners, despite the reported high frequency of educational training in, and use of, Western and CM diagnostic techniques [69].

Two identified papers focused on teaching aspects of practitioner communication skills and the integration of complementary and conventional medicine in CM schools. Using a pre-course ‘semi-structured questionnaire’ plus surveys after an educational intervention, 62 students in Israel reported on how the communication gap with conventional physicians and CM practitioners could be improved [70]. This study found that CM practitioners perceived themselves as better equipped to communicate with conventional health care practitioners when critical thinking, patient-centered care, and communicating skills were emphasized in their course of undergraduate study [70]. In addition, a Canadian study published findings derived from 28 directors of colleges of CM. The author reported that student’s ability to understand research findings, to rely on high quality research and to engage in continuing education was important in communicating with conventional care providers [71].

Meanwhile, the need for schools to adopt research literacy and evidence based practice competencies was the focus of three papers. One study that examined the attitudes towards research and scholarly activity of 202 faculty academics in an Australian CM college reported low confidence in undertaking research [72]. Respondents in this Australian study perceived research as important to their personal professional goals (86.0%) although confidence in being able to undertake research was less common (56.5%). The perceived importance of publication of research to the respondents’ personal professional goals was also notably high (80.0%) although confidence in their own ability to produce research publications was lower (52.9%) [72]. Another study conducted in the US examined the approaches of 9 CM colleges to develop evidence-informed skills and knowledge with the aim of developing both students and faculty to critically appraise evidence and then employ that evidence to guide clinical practice [73]. This study found that in developing the framework for their educational programs, educational institutions used strategies that were viewed critical for success, including making them multifaceted and unique to their specific institutional needs. It was found that these strategies, in conjunction with existing instructional approaches, were of practical use in other CM and non-CM academic environments where administrators were considering the introduction of research literacy and EBP competencies into their curricula. Training programs and workshops were found to be the most useful way to train faculty in evidence based medicine and research literacy [74]. Finally, one reviewed paper reported on the educational competencies and institutional teaching strategies that had been developed and implemented to enhance research literacy at all nine R25-funded CM institutions in the US [73]. This study found that while each institution designed approaches suitable for its own research culture, the guiding principles were similar across all, and the need to develop evidence-informed skills and knowledge was important to help students and faculty to critically appraise evidence and then use that evidence to guide their clinical practice. The strategies adopted by these institutions included a need for course content to be conducive to reinforcing EBM competencies using spiral learning strategies, and that faculty were willing to learn and teach EBM skills [73].

Application of existing and new educational theory, methods and technology in CM

The changing role of the trainer/lecturer in didactic and clinical subjects, the application of existing and new educational theory and problem-based learning within the context of CM curricula in bachelor and medical college programs, as well as the growing use of learning technologies was highlighted by six papers included in the review. In one study three educational interventions testing new teaching methods were introduced in an ayurveda program [75]. The instructional methods that were evaluated were an integrative module on cardiovascular physiology, case-stimulated learning and classroom small group discussion with findings showing the development of testable integrative teaching methods is possible in the context of Ayurveda education [75]. In contrast, findings from an educational intervention, the implementation of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) model as well as a patient-centered training approach within traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioner education in one Taiwanese medical school, found this examination approach effective in evaluating, teaching, and certifying TCM clinical competencies to improve the quality of TCM practices. In this study the training program subjects included TCM internal medicine, TCM genecology, TCM paediatrics, TCM dietetics, acupuncture, TCM orthopaedics, and traumatology [76].

When it comes to resources and the use of technologies, Wardle’s 2014 study used focus groups with current and recent students of 4-year naturopathic degree programs in Australia to ascertain how they interact with clinical teaching materials, and their perceptions and attitudes towards teaching materials in naturopathic education. This study described a desire among naturopathy students for existing curriculum to focus on evidence-based approaches and information that both supported and was critical of traditional naturopathic practices. These students remained largely ambivalent about new teaching technologies and preferred that these develop organically as an evolution from printed materials, rather than depart dramatically and radically from these previously established materials [17]. CM student’s preferred learning methods are often based on levels of computer skills and experience, their current use of computers as an educational tool, and attitudes regarding the role of computers in medical education according to a cross sectional survey study from a 27-item questionnaire distributed to 1–4-year Osteopathic medical students in the US [77]. One ethnographic study based on interviews conducted in the Australian university system with Naturopathic Faculty found an openness to the utilization of a number of technologies for flexible learning, including wikis, podcasts and synchronous audio-based online interactions [78]. In contrast, another study in the US found acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapy faculty lacked awareness of the capabilities of online education and the elements of good online learning and described a perception that what they taught could not be taught online because of its hands-on kinaesthetic requirements such as palpation [79].

Future challenges facing CM education

Lastly, one paper included in our review identified some of the challenges ahead for the Australian naturopathic profession including naturopathic education, the changing student body in naturopathic education, naturopathic student expectations, and the growing tension between traditional and scientific evidence [80]. This study, involving semi-structured interviews with 20 naturopaths, found that participants articulated a paradox whereby on the one hand, they supported the teaching of increased levels of biomedical sciences in naturopathic education, yet also complained of the trend of contemporary naturopathic education to “become more scientific” – a trend they attributed to their desire for the discipline to be “accepted in the university sector”. The participants claimed that such a development would be undertaken at the expense of the philosophical underpinnings of the profession. The authors found the continued development of minimum standards of practice and education that value traditional naturopathic principles and philosophies in tandem with the development of appropriate regulatory regimes, was vital in ensuring continued ethical and effective clinical practice.

Quality of papers

Based on the STROBE reporting guidelines [60] the quantitative papers included in this study, while rich in design, descriptive data and discussion of results exhibited a broad weakness in stating clear objectives. In addition, statements and acknowledgement of bias were mostly absent. Other elements commonly missing from these papers were descriptions of statistical methods and generalisability leaving a general impression of low quality among the included papers. Based on the SRQR [62] tool for evaluating qualitative studies, all selected papers omitted a discussion on the qualitative approach and research paradigm used. A description of researcher characteristics and reflexivity, and techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis were mostly missing. In addition, potential sources of influence or perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions and how these were managed were also under-reported across this collected literature. In addition, a lack of reporting on sources of funding and other support, the role of funders in data collection, interpretation, and write-up were other weaknesses identified. The application of the MMAT critical appraisal tool for the mixed methods studies [63] in this instance found all papers used, included and reported appropriate sources of data relevant to answer the research question, took into account the context in data analysis, used appropriate sampling to answer the research question, and integrated qualitative and quantitative data and/or results. On the other hand, only some papers applied features of the tool such as data analysis relevant to answer the research question, and only a few reported on complete outcome data, or dropout rate, reported on recruitment minimizing bias and appropriate follow-up, used appropriate randomization, appropriate measurement, sample representative of the population, or appropriate measurement. No papers reported on the reflexivity of researchers, nor concealment allocation, and only a few reported on the mixed method design relevant to answer the research questions, integrated the mixed qualitative and quantitative data and results nor took into consideration any limitations associated with this integration, leaving an overall impression of poor quality.

Discussion

This critical integrative review highlights two key issues and large current empirical gaps. Firstly, given the growing popularity of CM and as a consequence the growth in CM education, there is very sporadic coverage of research in the CM education field. Across the 18 included papers, research from 7 countries is represented with 4 of those countries having only one identified relevant paper. In addition, the quantity and quality of available evidence invariably relates to disparate, random and unrelated parts of CM education philosophy and practice. Our review findings highlight that much of the research is now relatively dated [81]. In addition, there is extreme diversity in the represented professions and ultimately the quality of papers. Many papers were excluded due to inconsistencies between title, abstract and findings [82]. Some papers were relevant but not published in peer reviewed journals and thus excluded; highlighting how in a maturing field there is a need to publish in both professional industry journals and the peer reviewed literature. One such example was the result of a survey of ‘profession-wide’ educational acupuncture institutions in the US as well as an extensive literature review, subject matter expert interviews, community discussions, strategic planning, analysis, and evaluation, that called for the development of educational competencies [83]. Others examples were the Survey on Inter-institutional and Interprofessional Relationships of Accredited Complementary and Alternative Medicine Schools and Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine Programs [84], the National Education Dialogue to Advance Integrated Health Care: Creating Common Ground [84], the Project for Inter- Institutional Education Relationships [85]: Examples of Real Life Inter-Institutional Collaborations [84], and the Credentialing Licensed Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine Professionals for Practice in Healthcare Organizations: An Overview and Guidance for Hospital Administrators, Acupuncturists and Educators [84].

Our review identified that whilst educational standards and practices were considered within original research articles related to CM, this was mostly as part of the contextual discussion of findings of related but not directly relevant CM research. This pattern was observed both in the grey literature [86, 87] and peer-reviewed publications [8, 15, 54, 67, 88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99]. One striking example of research emphasizing information related to CM education but collected in other settings, is by Wardle and colleagues in which practicing naturopaths were interviewed regarding multiple issues including the public misconception of the role of naturopathic medicine, the devaluation of naturopathic philosophy as a core component of naturopathic practice, the pressure to move towards an evidence-based medicine model focused on product prescription, as well as naturopathic education. In this paper, much of the data collected related to CM education but came from a broader research question and sample than research which focuses specifically on education and relevant stakeholders. Similarly, in Steel’s 2011 article, 12 naturopaths in current clinical practice were interviewed on the sources of information used in clinical practice, and the participants’ perceptions of these sources. This elicited comments about naturopathic education as well as concluding comments by the authors in relation to naturopathic education [89].

Another major finding from this review is that the robust and mature research exploring educational technology and e-learning that is taking place in medical and or allied health (nursing, midwifery, pharmacy) education research is clearly absent within the CM educational research field. Research within conventional medical and allied health education has explored the value of educational technology in place of traditional face-to-face delivery or within clinical training [100, 101]. Moreover, there is also now substantial research examining the culture change for stakeholders in medical and allied health education, with qualitative research drawing on the results of surveys reporting of student and staff characteristics for developing faculty, or reporting on digital literacy and other academic processes as a consequence of e-learning [102, 103]. In addition, many case studies of educational interventions have been published using some aspect of e-learning in medical or health services training [104]. Finally there are many original research papers examining the challenges facing medical education due to the clear trends of changing student behaviour, often as a result of the use of learning technologies [105,106,107]. Further, there are numerous studies exploring more effective delivery methods, and the development of critical thinking [108, 109]. None of these areas of research relating to learning technologies have being reported nor evaluated in CM at present. This highlights that there is a significant discourse relating to andragogy and learning technologies taking place in arenas not too distant from CM education but not within CM practitioner education itself. These findings also highlight that most of the research on CM education is in non-CM environments or in arenas possibly similar to CM, such as nursing or Integrative Medicine but not CM.

Consequences

As identified in this review, the current evidence evaluating the procedures, effectiveness and outcomes of CM education remains limited in many significant areas despite the high levels of use of CM in the community and the thriving nature of CM educational institutions globally. As a result, there are a number of challenges previously described by commentators [8] which impact on the growth and sustainability of CM education. In particular, the ongoing absence of strategy in CM education research ensures a gap in the available knowledge and contributes to uncertainty for CM education leaders, policy makers and other health professionals as to the needs of employers and the market [8]. Furthermore, our review reveals the current empirical data regarding CM education as affording only a limited, superficial understanding of contemporary CM education highlighting the sporadic spread and apparent scarcity of research in this field. Our research suggests that possibly practitioners and users of CM for so long out of mainstream health care activity in Western societies [3, 110, 111] hold unique values attitudes to health [79]. In addition, it possibly suggests that there is in general a slower adoption of technology, and a stronger culture of resistance to change [78]. Yet it also points to a selective use of technologies as there is growing evidence of innumerable CM consultations taking place online [112, 113]. This relatively low amount of empirical data pertaining to CM research in general may also be explained by the fact that there are few research active CM academics [8] and this is underpinned by a lack of perceived relevance of research in CM educational entities that are for the most part more technical colleges with academics often focused on technical and clinical expertise rather than empirical research activities [72].

Research opportunities and directions

The findings of this review highlight that there are significant gaps in the existing research examining CM education. There is a need to establish a strategic research agenda in this field. To effectively address these gaps it is important that future research build on a strong understanding of the unique educational environment of CM courses, colleges and universities. A key foundational step to developing a better understanding of the effectiveness of CM education is to more clearly identify current CM educational provision. Building upon a health services research approach, future research is required which examines the characteristics, attitudes, preferences, experiences and motivations of modern CM students. There is an urgent need to understand CM educational institutions geographical location, enrolment patterns, andragogy, their size and scope as well as international similarities and differences. This is particularly important given the as yet largely unexplored and potentially unique characteristics of CM educational institutions and their similarities or differences with other health services education (nursing, pharmacy), the potential size of the CM education market and the numbers of graduates entering CM professions. Alongside this, a closer examination of the use and reliance on technologies, faculty attitudes to technologies and change, the demographics, psychographics and the values of faculty at CM colleges is needed. Moving forward there is a need to understand how changing educational trends relate to CM, if CM educational settings are distinct because of their unique student body, the difference between training CM practitioners and training people about the use of CM, the broad and differing landscape of CM education provision across the world, to what degree are CM educational institutions influenced by the broader trends taking place in education globally? CM education is not immune or separate from the changes taking place in education globally (Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), flipped classrooms, constructivist education theories and the implementation of problem based learning [114,115,116,117,118,119] and this points the way forward for CM education research. Such an examination of CM education must also include the cultural diversity of education provision, local regulations and nuances. A broader knowledge of how health services education informs CM education, the degree to which research and evidence in health services education can be scaled to CM education [120], and how the foundational sciences are taught in CM institutions is also required. It might be beneficial for Colleges to explore strategies to develop faculty in areas such as e-learning technologies, research literacy and evidence-based practice skills, and students in health literacy and information literacy. For this, faculty and administrative champions are needed, as are early adopters and change-leaders. More needs to be known about the sheer breadth of educational provision in CM internationally, the range of award options with courses currently available at undergraduate, and postgraduate level, the relationship between prerequisites, the content of the program and the graduate outcome, as well as pathways include promoting CM-related courses in higher education generally, such as meditation, or somatics. General education courses to benefit all students and entry requirements and education prior to CM training, which may improve science literacy, publication productivity, professional standards. In addition more needs to be known about the financial drivers of for profit private equity educational institutions in the CM field.

Limitations

These findings can be contextualised within identifiable limitations. Searching literature related to CM can be challenging due to the lack of a consistent international definition. Further, there are many relevant studies, papers and commentaries that are not peer-reviewed and fell outside the scope of this review. There were 12 papers in this review that were identified through manual searching. This possibly highlights that despite research being conducted in this area, papers may not be published in journals which are indexed in commonly searched research databases. Whether this is due to a perception amongst CM-specific or health professional education journals that research in CM education falls outside of their relative scope and prefer to focus on clinical questions or the researchers are not targeting these other journals is not clear. Moreover, the application of three critical appraisal tools created challenges of inclusion and exclusion related to quality. In the case of the SRQR and MMAT, these guidelines were written for pure qualitative and mixed methods research, yet the papers in this review were published in public health and education journals. As such, the structure and content of the included qualitative and mixed methods articles may have been modified to suit the journal style guide and intended audience and the reporting guidelines may have been compromised as a result. For this reason, the low score for some of these articles may be due to reporting omissions of necessity rather than true gaps in methodology. Another limitation identified is that conducting research that crosses national borders comparisons become challenging. There are quite different standards for entry level and practice even between the various professions from country to country. The findings of the article reflect a symptom of wider issues and general statements are necessarily hesitant in this context. Nevertheless, where possible these limitations have been mitigated through attending to systematic review best practice, and as a consequence the relevance and value of the findings presented here for contemporary healthcare education provision should not be minimised.

Conclusion

Despite the high rates of CM use worldwide and growing interest in CM education, only a sporadic and under-developed body of original research has examined relevant issues to date and there is a need for both a growth in research activity and a clear coordinated research agenda in this important topic area. The significance of growing such a research program around the broad topic of CM education is essential to ensuring an adequately trained and educated CM workforce capable of realising an important role in the broader, coordinated and inter-professional health care system.

Abbreviations

- CM:

-

Complementary Medicine

- EBM:

-

Evidence Based Medicine

- HREC:

-

Human Research Ethics Committee

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- MOOC:

-

Massive Open Online Course

- OSCE:

-

Objective Structured Clinical Examination

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SRQR:

-

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- TCM:

-

Traditional Chinese Medicine

- US:

-

United States

References

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;79:1.

Nguyen LT, Davis RB, Kaptchuk TJ, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine and self-rated health status: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):399–404.

Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008(12):1–23. [published Online First: 2009/04/14]

Burke SR, Myers R, Zhang AL. A profile of osteopathic practice in Australia 2010–2011: a cross sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):227.

Harris P, Cooper K, Relton C, Thomas K. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(10):924–39.

Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Mullner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012;12(1):45–56.

Reid R, Steel A, Wardle J, Trubody A, Adams J. Complementary medicine use by the Australian population: a critical mixed studies systematic review of utilisation, perceptions and factors associated with use. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):176.

Wardle J, Steel A, Adams J. A review of tensions and risks in naturopathic education and training in Australia: a need for regulation. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(4):363–70.

Myers SP, Xue CC, Cohen MM, Phelps KL, Lewith GT. The legitimacy of academic complementary medicine. Med J Aust. 2012;197(2):69–70.

ECNH. Endeavour College of Natural Health Australia2017 [Available from: http://www.endeavour.edu.au. Accessed 2 Mar 2019.

NUNM. National University of Naturopathic Medicine USA2017 [Available from: https://nunm.edu/. Accessed 2 Mar 2019.

CNM. College of Naturopathic Medicine 2017 [Available from: http://www.naturopathy-uk.com. Accessed 2 Mar 2019.

SCM-HKU. School of Chinese Medicine, The University of Hong Kong 2017 [Available from: http://www.scm.cuhk.edu.hk/zh-tw/. Accessed 2 Mar 2019.

McCabe P. Complementary and alternative medicine in Australia: a contemporary overview. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2005;11(1):28–31.

Breakspear I. Training the next generation: advanced diplomas or degrees? Aust J Herb Med. 2013;25(4):168–71.

James J, Murray I. What national registration means for a professional association-the AACMA view; 2011.

Wardle JL, Sarris J. Student attitudes towards clinical teaching resources in complementary medicine: a focus group examination of Australian naturopathic medicine students. Health Inf Libr J. 2014;31(2):123–32.

Daniel R, Morris D, Jobst KA. Distinguishing between complementary and alternative medicine and integrative medicine delivery: the United Kingdom joins world leaders in professional integrative medicine education. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17(6):483–5.

Hollenberg D. Uncharted ground: patterns of professional interaction among complementary/alternative and biomedical practitioners in integrative health care settings. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(3):731–44.

Bishop FL, Amos N, Yu H, Lewith GT. Health-care sector and complementary medicine: practitioners' experiences of delivering acupuncture in the public and private sectors. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13(3):269–78.

DiMaria-Ghalili RA, Mirtallo JM, Tobin BW, Hark L, Van Horn L, Palmer CA. Challenges and opportunities for nutrition education and training in the health care professions: intraprofessional and interprofessional call to action. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5):1184S–93S.

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2014;348:–g3725.

Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4–15.

Hall Giesinger C, Adams Becker S, Davis A, Shedd L. Scaling Solutions to Higher Education's Biggest Challenges: An NMC Horizon Project Strategic Brief. Volume 3.2. New Media Consortium; 2016.

Brändle T. How availability of capital affects the timing of enrollment: the routes to university of traditional and non-traditional students. Stud High Educ. 2016;42(12):2229–49.

Brosnan C, Turner BS. Handbook of the sociology of medical education. Routledge; 2009.

Gros B, Garcia I, Escofet A. Beyond the net generation debate: a comparison between digital learners in face-to-face and virtual universities. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2012;13(4):190–210.

Cornelius S. The challenges of learner-centered teaching in virtual classrooms. World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications; 2014.

Lister M. Trends in the design of E-learning and online learning. J Online Learn Teach. 2014;10(4):671–80.

Pathipati AS, Azad TD, Jethwani K. Telemedical Education: Training Digital Natives in Telemedicine. J Med Int Res. 2016;18(7):e193. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5534. [published Online First: 2016/07/14]

Liebenberg H, Chetty Y, Prinsloo P. Student access to and skills in using technology in an open and distance learning context. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2012;13(4):250–68.

Anderson T, Dron J. Learning Technology through Three Generations of Technology Enhanced Distance Education Pedagogy. European Journal of Open, Distance and e-learning. 2012;15(2).

Parkes M, Stein S, Reading C. Student preparedness for university e-learning environments. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:1–10.

Downing JJ, Dyment JE. Teacher educators' readiness, preparation, and perceptions of preparing preservice teachers in a fully online environment: an exploratory study. Teach Educ. 2013;48(2):96–109.

McKee CW, Tew WM. Setting the stage for teaching and learning in American higher education: making the case for faculty development. New Dir Teach Learn. 2013;2013(133):3–14.

Black-Fuller L, Taube S, Koptelov A, Sullivan S. Smartphones and pedagogy: digital divide between high school teachers and secondary students. US-China Educ Rev. 2016;6(2):124–31.

Lefoe G, Philip R, O'Reilly M, Parrish D. Sharing quality resources for teaching and learning: A peer review model for the ALTC Exchange in Australia. Aust J Educ Technol. 2009;25(1).

Phillips D, Forbes H, Duke M. Teaching and learning innovations for postgraduate education in nursing. Collegian (Australia: Royal College of Nursing). 2013;20(3):145–51.

Adams T, Demaiter EI. Skill, education and credentials in the new economy: the case of information technology workers; 2008.

Ensminger DC, Surry DW, Porter BE, Wright D. Factors contributing to the successful implementation of technology innovations. J Educ Technol Soc. 2004;7(3):61–72.

Loh KP, Ghorab H, Clarke E, Conroy R, Barlow J. Medical Students' knowledge, perceptions, and interest in complementary and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(4):360–6.

Kim DY, Park WB, Kang HC, Kim MJ, Park KH, Min BI, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in the undergraduate medical curriculum: a survey of Korean medical schools. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY). 2012;18(9):870–4.

Sansgiry SS, Mhatre SK, Artani SM. Use of and attitude toward complementary and alternative medicine: understanding the role of generational influence. Altern Ther Health Med. 2012;19(3):10–5.

Adams J, Broom A. The status of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in biomedical education: towards a critical engagement. Handbook Sociol Med Educ. 2009.

Adams J. An exploratory study of complementary and alternative medicine in hospital midwifery: models of care and professional struggle. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2006;12(1):40–7.

Hanna L-A, Hall M, McKibbin K. Pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitudes, and use of complementary and alternative medicines. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2013;5(6):518–25.

Al-Dulaimy SNY, Hassali MAA, Awaisu A. An evaluation of senior pharmacy students' perceptions and knowledge of complementary and alternative medicine at a Malaysian university. J Aust Traditional-Medicine Soc. 2012;18(1):41.

Harris IM, Kingston RL, Rodriguez R, Choudary V. Attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine among pharmacy faculty and students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(6):129.

Adams J, Tovey P. Complementary and alternative medicine in nursing and midwifery: towards a critical social science. Routledge; 2014.

Buchan S, Shakeel M, Trinidade A, Buchan D, Ah-See K. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by nurses. Br J Nurs. 2012;21(10):672–5.

Lindquist R, Snyder M, Tracy MF. Complementary & alternative therapies in Nursing. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2013.

Adams J, Tovey P. Nurses' use of professional distancing in the appropriation of CAM: a text analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9(3):136–40.

Helms JE. Complementary and alternative therapies: a new frontier for nursing education? J Nurs Educ. 2006;45(3):117.

McCabe P. Nursing and naturopathy at La Trobe: the challenge of multiparadigm education. Int J Nurs Pract. 2001;7(5):361.

Templeman K, Robinson A, McKenna L. Integrating complementary medicine literacy education into Australian medical curricula: student-identified techniques and strategies for implementation. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21(4):238–46.

Dannenfeldt G, Stewart J, McHaffie J, Gibson-van Marrewijk K, Stewart K, Hipkins R. Addressing obstacles to success: implementing change in science delivery; 2009.

Baker N. Build it and they will use it: A case study in getting bang for your buck in educational technology choices. In EdMedia+ Innovate Learning. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE); 2014. pp 72–76.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Milanese SF, Grimmer-Somers K, Souvlis T, Innes-Walker K, Chipchase LS. Is a blended learning approach effective for learning in allied health clinicians? Phys Ther Rev. 2014;19(2):86.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–8.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51.

Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, Bush PL, Vedel I, Pluye P. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the mixed methods appraisal tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):500–1.

Grace S, Vemulpad S, Beirman R. Primary contact practitioner training: a comparison of chiropractic and naturopathic curricula in Australia; 2007.

Viksveen P, Steinsbekk A. Undergraduate homeopathy education in Europe and the influence of accreditation. Homeopathy. 2011;100(4):253–8.

Rowe T. North American homeopathic educational survey. Am J Homeopath Med. 2009;102(2):65–74.

McCabe P. Education in naturopathy and western herbal medicine in Australia: results of a survey of education providers. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(3):168–75.

Viksveen P, Steinsbekk A, Rise MB. What is a competent homeopath and what do they need in their education? A qualitative study of educators' views. Educ Health (Abingdon, England). 2012;25(3):172–9.

Grace S, Vemulpad S, Beirman R. Training in and use of diagnostic techniques among CAM practitioners: an Australian study. J Alternat Complement Med. 2006;12(7):695–700.

Frenkel M, Ben-Arye E, Geva H, Klein A. Educating CAM practitioners about integrative medicine: an approach to overcoming the communication gap with conventional health care practitioners. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY). 2007;13(3):387–91.

Toupin AK, Gaboury I. A survey of Canadian regulated complementary and alternative medicine schools about research, evidence-based health care and interprofessional training, as well as continuing education. BMC Complementary And Alternative Medicine [serial online] 2013; Available from: Academic OneFile, Ipswich, MA 2013.

Steel A, Hemmings B, Sibbritt D, Adams J. Research challenges for a complementary medicine higher education institution: results from an organisational climate survey. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7(5):442–9.

Zwickey H, Schiffke H, Fleishman S, Haas M, Cruser dA, LeFebvre R, et al. Teaching evidence-based medicine at complementary and alternative medicine institutions: strategies, competencies, and evaluation. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(12):925–31.

Long CR, Ackerman DL, Hammerschlag R, Delagran L, Peterson DH, Berlin M, et al. Faculty development initiatives to advance research literacy and evidence-based practice at CAM academic institutions. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(7):563–70.

Joshi H, Singh G, Patwardhan K. Ayurveda education: evaluating the integrative approaches of teaching Kriya Sharira (Ayurveda physiology). J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2013;4(3):138.

Chen Y-L, Hou MC, Lin S-C, Tung Y-J. Educational efficacy of objective structured clinical examination on clinical training of traditional Chinese medicine – a qualitative study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21:147–53.

Forman LJ, Pomerantz SC. Computer-assisted instruction: a survey on the attitudes of osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(9):571–8.

Grant A, O'Reilly M. From herb garden to wiki: responding to change in naturopathic education through scholarly reflection. J Scholarsh Teach Learn. 2012;12(4):76–85.

Schwartz J. Faculty perception of and resistance to online education in the fields of acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapy. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2010;3(3):20–31.

Wardle JL, Adams J, Lui CW, Steel AE. Current challenges and future directions for naturopathic medicine in Australia: a qualitative examination of perceptions and experiences from grassroots practice. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:15.

Mills E, Hollyer T, Saranchuk R, Wilson K. Teaching evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine (EBCAM); changing behaviours in the face of reticence: a cross-over trial. BMC Med Educ. 2002;2(1):2.

Zhang K, Zheng J. Analysis on application of PBL in teaching of Zhenjiuxue (science of acupuncture and moxibustion) and establishment of a new education model. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2013;33(5):469–72.

Ruhe V, Stumpf S, Jabbour MJ. Competency-based education in acupuncture and oriental medicine. Am Acupuncturist. 2014;68:21–31.

ACIH. Academic Collaborative for Integrative Health: ACIH 2018 [Available from: https://integrativehealth.org/publications/. Accessed 3 Mar 2019.

Spiers J. Expressing and responding to pain and stoicism in home-care nurse-patient interactions. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(3):293–301.

Siegfried NL, Hughes G. Herbal medicine, randomised controlled trials and global core competencies. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(12):912–3.

Girard C. Christine Girard, ND: enriching education for naturopathic physicians. Interview by Frank Lampe and Suzanne Snyder. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16(2):66.

Sarris J, Wardle J. Clinical naturopathy: an evidence-based guide to practice. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

Steel A, Adams J. The interface between tradition and science: Naturopaths' perspectives of modern practice. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17(10):967–72.

Evans S. The story of naturopathic education in Australia. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8(4 Dec):234–40.

Melchart D, Worku F, Linde K, Wagner H. The university project Münchener Modell for the integration of naturopathy into research and teaching at the Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich. Complement Ther Med. 1994;2(3):147–53.

Dobos G, Tao I. The model of Western integrative medicine: the role of Chinese medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2011;17(1):11–20.

Wardle JJ, Weir M, Marshall B, Archer E. Regulatory and legislative protections for consumers in complementary medicine: lessons from Australian policy and legal developments. Eur J Integr Med. 2014;6(4):423–33.

Wardle J, Steel A, McIntyre E. Independent registration for naturopaths and herbalists in Australia: the coming of age of an ancient profession in contemporary healthcare; 2013.

Wardle JL, Steel AE, Adams J. Response to Holmes. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY). 2013;19(12):979–80.

Wardle J. The National Registration and accreditation scheme: what would inclusion mean for naturopathy and Western herbal medicine?: part I-the legislation. Aust J Med Herbalism. 2010;22(4):113.

Benjamin PJ, Phillips R, Warren D, Salveson C, Hammerschlag R, Snider P, et al. Response to a proposal for an integrative medicine curriculum. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(9):1021–34.

ACIH. Clinicians' & Educators' Desk Reference on the Integrative Health & Medicine Professions. Academic Collaborative for Integrative Health (ACIH); 2017.

Rosenthal BL, A. The Extent of Interprofessional Education in the Clinical Training of Integrated Health and Medicine Students: A Survey of Educational Institutions. Topics in Integrative Health Care. 2015;Vol. 6(1).

Nelson K, Wright T, Connor M, Buckley S, Cumming J. Lessons from eleven primary health care nursing innovations in New Zealand. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56(3):292–8.

Adams CL. A comparison of student outcomes in a therapeutic modalities course based on mode of delivery: hybrid versus traditional classroom instruction. J Phys Ther Educ. 2013;27(1):20–34.

Link TM, Marz R. Computer literacy and attitudes towards e-learning among first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:34.

Perlman A, Stagnaro-Green A. Developing a complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine course: one medical school's experience. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(5):601–5.

Gormley GJ, Collins K, Boohan M, Bickle IC, Stevenson M. Is there a place for e-learning in clinical skills? A survey of undergraduate medical students' experiences and attitudes. Med Teach. 2009;31(1):e6–12.

Greenfield B, Musolino GM. Technology in rehabilitation: ethical and curricular implications for physical therapist education. J Phys Ther Educ. 2012;26(2):81.

Friedl KE, O'Neil HF. Designing and using computer simulations in medical education and training: an introduction. Mil Med. 2013;178(10S):1–6.

Hutchings M, Quinney A. The flipped classroom, disruptive pedagogies, enabling technologies and wicked problems: responding to 'the bomb in the Basement'. Elec J e-Learning. 2015;13(2):105–18.

Serrat MA, Dom AM, Buchanan JT Jr, Williams AR, Efaw ML, Richardson LL. Independent learning modules enhance student performance and understanding of anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7(5):406–16.

Wheeler LA, Collins SK. The influence of concept mapping on critical thinking in baccalaureate nursing students. J Prof Nurs. 2003;19(6):339–46.

Adams J, Barbery G, Lui C-W. Complementary and alternative medicine use for headache and migraine: a critical review of the literature. Headache. 2013;53(3):459–73.

Xue CC, Zhang AL, Lin V, Da Costa C, Story DF. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national population-based survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(6):643–50.

Richter KP, Shireman TI, Ellerbeck EF, Cupertino AP, Catley D, Cox LS, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e113.

Epstein EG, Sherman J, Blackman A, Sinkin RA. Testing the feasibility of skype and FaceTime updates with parents in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(4):290–6.

Rodriguez CO. MOOCs and the AI-Stanford like courses: two successful and distinct course formats for massive open online courses. Eur J Open Dis E-Learning. 2012.

Veletsianos G, Kimmons R. Assumptions and challenges of open scholarship. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2012;13(4):166–89.

Halac HH, Cabuk A. Open courseware in design and planning education and utilization of distance education opportunity: Anadolu University experience. Turk Online J Dist Educ. 2013;14(1):338–50.

Johnson L, Adams S. Technology Outlook for UK Tertiary Education 2011-2016: An NMC horizon report regional analysis. New Media Consortium 2011.

Johnson LAS, Cummins M. Technology Outlook for Australian Tertiary Education 2012–2017: An NMC Horizon Report Regional Analysis New Media Consortium [serial online] January 1, 2012; 2012.

Jones R, Fox C, Levin D. National Educational Technology Trends: 2011. Transforming Education to Ensure All Students Are Successful in the 21st Century. State Educational Technology Directors Association. 2011.

Verma S, Paterson M, Medves J. Core competencies for health care professionals: what medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy share. J Allied Health. 2006;35(2):109–15.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based was conducted as part of the authors PhD at the Faculty of Health University of Technology Sydney, and part of a broader research piece exploring CM education in the US and Australia. We are grateful to the Endeavour College of Natural Health and National University of Natural medicine for their time and commitment to the research in their profession.

Funding

No funding was required for this paper.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG conceptualised the analysis and the paper, undertook the analysis. JA and AS assisted with interpretation of the findings of the analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and finalising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was granted from the Human Research Ethics Committees of the University of Technology Sydney (ETH16–0477 – 12,220,214) and the IRB of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM IRB# AG05052017).

Consent for publication

No consent for publication was required for this analysis.

Competing interests

JA and AS are members of the editorial board (Associate Editor) of this journal. The authors have no further competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, A.C., Steel, A. & Adams, J. A critical integrative review of complementary medicine education research: key issues and empirical gaps. BMC Complement Altern Med 19, 73 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2466-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2466-z