Abstract

Background

Due to the lack of strong evidence on safety and efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches, the use of CAM in women during pregnancy could be hazardous for mother and fetus. Meanwhile, little is known regarding the patterns, the reasons and the factors affecting use of CAM among pregnant women in Iraq.

Methods

A cross sectional survey design was used to carry out face-to-face interviews with 335 consecutive pregnant women. The questionnaire comprised of three sections: socio-demographic characteristics, pregnancy-related aspects and the patterns and attitudes towards use of CAM. Determinants of CAM use were assessed through the logistic regression analysis.

Results

Three hundred thirty-five pregnant women completed the questionnaire. 56.7 % reported using at least one form of CAM modalities. In total, 24 different types of CAM were used; with herbal medicine (53.7 %) and multivitamins (36.3 %) the most commonly used modalities. From the logistic regression analysis, the variables positively associated with CAM use were: rural residence (odds ratio (OR) 2.0, p < 0.01), no occupation (OR 2.7, p < 0.05), high income (OR 2.0, p < 0.05), perceived healthy status (OR 2.6, p < 0.05) and ever use of contraception (OR 2.0, p < 0.01). Only 0.5 % of CAM users disclosed their CAM use to physicians.

Conclusions

The proportion of CAM users among pregnant women is relatively high and it is important to learn what types of CAM they use. However, disclosure of CAM use was extraordinarily low. Given the low rate of disclosure, it should be ensured that physicians establish good level of communication with pregnant women and have adequate knowledge of CAM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in pregnant women is increasing and is widespread in developed and developing countries [1–3]. These women take a wide range of CAM such as herbs, vitamins and minerals, massage, aromatherapy, acupuncture, homeopathic remedies and Reiki as well as psychological, physical and spiritual techniques [4–6]. However, given the global initiative concerning evidence based medicine and the lack of robust data on safety and efficacy of CAM approaches, health professionals and policymakers have become increasingly concerned about the use of CAM by women during pregnancy [7].

Recent studies reveal that over one third of pregnant women in the USA used one or more CAM therapies during previous year [8, 9]. In the UK, 57.1 % of women reported their CAM use during pregnancy [6]. Surveys from Middle East countries have reported that prevalence of CAM use during pregnancy is 40.0 % in Palestine [10], about 75 % in Jordan [11], and 22.3 % in Iran [12]. However, little is known about the extent to which CAM is used by women during pregnancy in Iraq. It is important to obtain history on CAM use at any time but particularly in pregnancy, in order to provide proper counselling to the expecting mothers. Some of the CAM may have unrecognized effects on pregnancy or labor, have interactions with prescribed medications and have potentially serious complications on fetus.

Iraq, as an Arabian Gulf state, has witnessed a rapid socio-economic transition over the last two decades [13]. Since then, the Iraqi health care system has been seriously affected as a result of different wars, internal conflicts, international sanctions and political instability [14, 15]. Under Iraqi health delivery system, which has been on a centralized, curative and hospital-oriented model, maternity services are provided by public institutions and obstetricians’ private clinics that are widely distributed mainly in urban areas [16]. These events resulted in a substantial fall in major health indices and left a crippled health system struggling to meet population needs [14, 17]. The maternity care services in particular did not escape these damaging effects and continue to suffer from problems common throughout the health care system [18]. The antenatal care services in Iraq suffer from challenges common to the primary health care system [19]. These challenges are mainly related to inappropriate health service delivery including irrational use of health services, poor referral system, poor infrastructure, lack of management guidelines and poor hygiene [17, 20]. Other problems include health workforce challenges like poor qualification of health care providers, uneven distribution and rapid turnover of the health workforce and lack of continuing educational and professional development opportunities; and dearth of resources including shortage and low quality of medical supplies and inadequate financing [21]. Poor information technology and poor leadership are also major obstacles to the antenatal care [22]. This situation of health care sector in Iraq may affect the use of CAM among pregnant women.

The present study was planned to gain insights into the prevalence and factors leading to the use of CAM among pregnant women in Iraq. Additionally, the study was designed to bring to light CAM therapies which are most commonly used during pregnancy in the gulf country. The study was also purposely designed to identify the main sources of information recommending the use of CAM during pregnancy.

Methods

For this study, a cross-sectional survey was designed to collect information on the use of CAM among Iraqi pregnant women. The data was gathered in outpatient department of four hospitals located in Basrah, Iraq. Eligible participants of the study were Iraqi women who visited outpatient department to seek antenatal care services. Women who visited the hospitals for normal delivery, cesarean section or post-natal checkup were excluded from the study.

The survey questionnaire was designed in the English language and then translated into the Arabic language to best suit the target population. The Arabic version of questionnaire was validated by translation back into English, and the text was revised where necessary by three doctors who were not among authors of this study. Then it was piloted on a small group of 20 volunteers. In order to collect the information, one week training was given to eight surveyors mainly on ethics and data collection. Two surveyors were asked to gather data from each hospital. Before the interview, surveyors explained nature of the study to the participants and sought consent. The surveyors conducted the face-to-face interviews with the participants and fill out the questionnaire during the period of four weeks from November 13, 2014 to December 15, 2014.

The survey questionnaire comprised of 34 items, close and open-ended questions, divided into three sections: demographic characteristics, medical factors and questions on CAM related information. CAM related questions were asked to collect information on modalities of CAM used and frequency of CAM use, reasons for using CAM, satisfaction with usage, disclosure of CAM, supplier of CAM and source of CAM information. The collected data were coded and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 21. To analyze categorical variables related to CAM use, perceptions and attitudes, descriptive statistics (using n and percentage) were used. In order to see the relationship between CAM use and characteristics of the survey participants, chi-square test and logistic regression analysis were done considering P value <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

The characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. A total of 335 pregnant women were consecutively interviewed, with response rate of 83.96 %. The mean age was 26.1 ± 6.9, 74.6 % were aged ≤30 years, 59.7 % were living in urban areas, 89.3 % were housewife, 42.1 % had at least a middle school education and 35.8 % had household income ≤500,000 Iraqi Dirhams. In terms of medical characteristics, 45.1 % perceived themselves as healthy, 35.5 % had history of previous pregnancy, and 31.9 % used contraception ever.

Utilization of CAM

Table 1 illustrates utilization of CAM among study participants. In total 56.7 % of the pregnant women reported using CAM. 47.4 % of the CAM users aged 21–30 years, 53.7 % were living in urban areas, 93.7 % were housewife, 42.1 % had at least a middle school education, 40 % were from middle income group, 55.8 % perceived themselves healthy, 37.9 % had history of previous pregnancy, and 51.6 % never used contraception.

Factors affecting CAM use

Chi-square test revealed that residence of living, occupation, monthly income, perceived health status and ever use of contraception were associated with use of CAM (Table 1). Results of logistic regression analysis showing factors affecting the use of CAM are presented in Table 2. Rural residence of living (p<0.01), no occupation (p<0.05), higher monthly income (p<0.05), perceived healthy status (p<0.05), and ever use of contraception (p<0.01) were positively associated with the utilization of CAM.

Frequency and modalities of CAM use

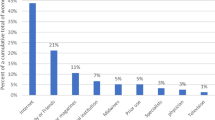

Figure 1 displays the frequency of CAM use among study participants. In total, 36.2 % used CAM twice a week, 35.7 % sometimes, 18.4 % daily and 9.7 % had used only once. Table 3 illustrates types of CAM modalities used by the pregnant women. Among CAM users, 53.7 % reported using herbs or natural products and 36.3 % used vitamins. Black seed (16.5 %), chamomile (16.2 %), cinnamon (10.8 %), castor oil plant (9.4 %) and ginger (8.3 %) were the most popular natural products.

Reason for using CAM and satisfaction

Reasons for using CAM and CAM satisfaction are shown in Table 4. About 43 % of the CAM users considered that it was not dangerous for their pregnancy, 28.6 % used for its effectiveness, 17.5 % for cultural reasons, and 10.6 % for the safety of fetus. Moreover, 83.7 % were satisfied with their CAM use.

Disclosure of CAM use

Table 5 illustrates CAM users’ disclosure of CAM to their doctors. In total only 0.5 % discussed their use of CAM with doctor. Reasons for the non-disclosure were: doctors did not ask 50.53 %, 28.2 % did not consider it important to disclose and 5.3 % were afraid of doctor’s response.

Source of information on CAM and supplier of CAM

Source of information on CAM and supplier of CAM are displayed in Table 6. For 46.3 % source of CAM information was friend, family 18.4 % and neighbor 16.3 %. In total, 63.8 % got CAM from shops and 33 % from CAM providers.

Discussion

This is the first study investigating knowledge, attitude and practice of CAM among pregnant women in Iraq, and is also the first work conducted with the aim of describing CAM users. The findings emphasize that the use of CAM during pregnancy is a common habit in the city of Basrah, Iraq. The study followed cross-sectional design and gathered information on the use of CAM by pregnant Iraqi women who visited outpatient department of four hospitals located in Basrah.

We found that 56.7 % of Iraqi women use at least one modality of CAM during pregnancy. Our results suggest significantly higher use of CAM among pregnant women in Iraq when compared to similar studies conducted in India, Oman, Zimbabwe, Palestine, Malaysia, Egypt, and Taiwan [10, 23–28]. However, it is lower than the studies done in Iran, Jordan, and UK [6, 11, 29]. These variations in the prevalence of CAM are understandable as difference in the proportion of CAM use could come from a number of factors, such as design of study, sample dynamics, and socio-demographic factors. This study also highlighted the extremely low level of communication, regarding use of CAM, between patients and their healthcare providers.

Likely predictors of CAM use among pregnant women in this study were residential area, occupation status and monthly income, which is consistent with previous studies [11, 25, 26]. We also found that pregnant women who perceived their health status as healthy tended to use CAM more than women who perceived their health status average or unhealthy. It makes sense as evidence suggests that pregnant women start using CAM, or more specifically herbs, in order to enhance their health status, increasing immunity, strengthening uterus ready for the labor and to avoid complications related to pregnancy like urinary tract infections and digestive disorders [29, 30]. Therefore, it is possible that pregnant women in this study did not perceive themselves healthy before using CAM; but once they started to use CAM, they felt more healthy and prepared for the labor. Furthermore, we demonstrated that women who ever used contraception were also more likely to be the CAM users, which is supported by the study conducted in Zambia [31]. In our study, more than 50 % of the pregnant women used herbal medication as a CAM modality. There is ample evidence suggesting high consumption of herbs, and that herbal products are the most common form of CAM, among pregnant women due to several reasons [32]. These studies suggest pregnant women use herbal supplements, such as raspberry leaf, ginger, chamomile, and cranberry juice, to gain strength in order to get prepared for the labor [30, 33]. The second most commonly used CAM modality among pregnant women was consumption of vitamins, which is also consistent with previous research [23, 24, 34]. We found that most of the CAM users were satisfied with the CAM used; and for 28 % of them effectiveness of the CAM use was main reason, as the most common reason for consumption was given as “not dangerous for pregnancy”. We also discovered that only about 18 % of the CAM users consumed it on daily basis while most of them utilized herbal products and vitamins for not more than twice a week. Our results reveal that about 64 % of the CAM users could get CAM from marketplace, which highlights the easy availability of CAM, especially herbal products, in the region. Additionally, our results show that most common source of CAM information was friends and family, which is supported by the previous study conducted by Holst et al. [35].

CAM users in our sample used various herbal therapies during pregnancy. The most popular herbal therapy was consumption of black seed and chamomile. Al-Riyami et al. report that pregnant women could use black seed during pregnancy against infections or as nutritional supplement while chamomile as a relaxant [23]. Literature suggest that herbal products could be harmful to the mother and fetus if consumed during pregnancy because herbs contain pharmacologically active substances [36]. Herbal supplements like garlic, ginger and chamomile have anti-platelet and anticoagulant properties so there is an increased risk of prolonged clotting time and bleeding [37]. Hypertensive and hyperglycemic characteristics of licorice may increase the complications of pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes respectively [38]. Moreover, there is also an increased risk of preterm labor and miscarriage among regular users of chamomile and licorice [39]. However, pregnant women consider herbs safer than conventional medications due to their extensive experience with and belief in herbal products [40]. Many pregnant users of CAM are unaware of their side-effects because they consider it natural and risk-free [37, 41].

We also discovered extremely low proportion of CAM users disclosing their CAM use to the doctors – only 0.5 % did so. More than 50 % of the respondents did not discuss their use of CAM because their doctors did not ask them. Moreover, the CAM users did not think it was important to discuss with their health providers. Poor communication regarding CAM between patients and doctors in our sample could be attributed to the CAM users’ unawareness of adverse effects from alternative medications as only 42 % of them had middle school education. Therefore, it highlights the need to increase awareness of Iraqi women on the safe use of CAM during pregnancy. It is also crucial that health care providers should have basic understanding about CAM including herbal products, so that they can better recognize the risks associated with health seeking behavior of patients [42]. Additionally, we recommend that physicians, as qualified healthcare providers, should ensure good level of communication with patients for their safety.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, a bigger sample size would have been preferred if there were no constraints on time and resources. Nevertheless, we did our best by generating sample from four public hospitals of Basrah city. However, it does not represent the national population; therefore, the results cannot be applied to all Iraqi women. Our sample is also harmonized in terms of socio-demographic factors except for the occupation. Secondly, this study did not include individual benefits of each modality of CAM used by pregnant women. Instead, we focused on attitudes of CAM users towards CAM and conventional healthcare.

Conclusions

Results of the study underline that use of CAM is common during pregnancy in Iraq. In total, twenty-four different modalities of CAM were used for pregnancy-related health ailments, most frequently vitamins, black seed, chamomile and cinnamon. Moreover, extremely low level of communication between CAM users and their health care providers is worrisome, and demands that physicians should inquire their patients about the use of CAM. Due to scarcity of evidence in support of CAM benefits during pregnancy, it is very important to educate women on the safe use of CAM especially when pregnant women come from a low-literate population such as our sample. Based on the results of our research, we recommend that this area should further be studied using larger sample size.

Abbreviation

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine

References

Hemminki E, Mäntyranta T, Malin M, Koponen P. A survey on the use of alternative drugs during pregnancy. Scand J Public Health. 1991;19(3):199–204.

Hall HG, Griffiths DL, McKenna LG. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by pregnant women: a literature review. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):817–24.

Hall HG, Griffiths D, McKenna LG. Complementary and alternative medicine: Interaction and communication between midwives and women. Women Birth. 2015;28(2):137–42.

Pallivalappila AR, Stewart D, Shetty A, Pande B, Singh R, Mclay JS. Complementary and alternative medicine use during early pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;181:251–5.

Louik C, Gardiner P, Kelley K, Mitchell AA. Use of herbal treatments in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):439. e431-439. e410.

Hall HR, Jolly K. Women's use of complementary and alternative medicines during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Midwifery. 2014;30(5):499–505.

Adams J, Lui CW, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Wardle J, Homer C, Beck S. Women's use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: a critical review of the literature. Birth. 2009;36(3):237–45.

Holden S, Davis R, Yeh G. Pregnant Women's Use of Complementary & Alternative Medicine in the United States. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(5):A120–0.

Steel A, Adams J, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Frawley J, Gallois C. The influence of complementary and alternative medicine use in pregnancy on labor pain management choices: results from a nationally representative sample of 1,835 women. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(2):87–97.

Jaradat N, Adawi D. Use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Palestinian women. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150(1):79–84.

Amasha HA, Jarrah SS. The use of home remedies by pregnant mothers as a treatment of pregnancy related complaints: An exploratory study. Med J Cairo Univ. 2012;80(1):673–80.

Sattari M, Dilmaghanizadeh M, Hamishehkar H, Mashayekhi SO. Self-reported Use and Attitudes Regarding Herbal Medicine Safety During Pregnancy in Iran. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2012;7(2):45.

Amara J. Implications of military stabilization efforts on economic development and security: The case of Iraq. J Dev Econ. 2012;99(2):244–54.

Al Hilfi TK, Lafta R, Burnham G. Health services in Iraq. Lancet. 2013;381(9870):939–48.

Wilson JF. The health care revival in Iraq. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):825–8.

Alwan A. Health in Iraq: the current situation, our vision for the future and areas of work. Baghdad: Ministry of Health, 2. 2004.

WHO. Health System Profile-Iraq. Cairo: Egypt: World Health Organization-Regional Health System Observatory (WHO-EMRO); 2006.

Ali MM, Shah IH. Sanctions and childhood mortality in Iraq. Lancet. 2000;355(9218):1851–7.

Shabila NP, Al-Tawil NG, Al-Hadithi TS, Sondorp E, Vaughan K. Iraqi primary care system in Kurdistan region: Providers’ perspectives on problems and opportunities for improvement. BMC Int Health Human Rights. 2012;12(1):21.

Al-Dabbagh SA, Al-Taee WY. Risk factors for pre-term birth in Iraq: a case–control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6(1):13.

Alwan AD: [Health-sector funding: options for funding health care in Iraq]. 2008.

Raoof AM, Al-Hadithi TS. Antenatal care in Erbil city-Iraq: assessment of information, education and communication strategy. DMJ. 2011;5(1):31–40.

Al-Riyami IM, Al-Busaidy IQ, Al-Zakwani IS. Medication use during pregnancy in Omani women. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):634–41.

Inamdar I, Aswar M, Sonkar V, Doibale M. Drug utilization pattern during pregnancy. Indian medical gazette 2012. 2012;146:305–11.

Mureyi DD, Monera TG, Maponga CC. Prevalence and patterns of prenatal use of traditional medicine among women at selected harare clinics: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12(1):164.

Rahman AA, Sulaiman SA, Ahmad Z, Salleh H, Daud WNW, Hamid AM. Women's attitude and sociodemographic characteristics influencing usage of herbal medicines during pregnancy in Tumpat District, Kelantan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(2):330–7.

Orief YI, Farghaly NF, Ibrahim MIA. Use of herbal medicines among pregnant women attending family health centers in Alexandria. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2014;19(1):42–50.

Yeh H-Y, Chen Y-C, Chen F-P, Chou L-F, Chen T-J, Hwang S-J. Use of traditional Chinese medicine among pregnant women in Taiwan. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107(2):147–50.

Hashem Dabaghian F, Abdollahi Fard M, Shojaei A, Kianbakht S, Zafarghandi N, Goushegir A. Use and Attitude on Herbal Medicine in a Group of Pregnant Women in Tehran. J Med Plants. 2012;1(41):22–33.

Forster DA, Denning A, Wills G, Bolger M, McCarthy E. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy in a group of Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6(1):21.

Banda Y, Chapman V, Goldenberg RL, Stringer JS, Culhane JF, Sinkala M, Vermund SH, Chi BH. Use of traditional medicine among pregnant women in Lusaka, Zambia. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(1):123–8.

Bishop JL, Northstone K, Green J, Thompson EA. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy: data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Complement Ther Med. 2011;19(6):303–10.

Adawi DH: Prevalence and Predictors of Herb Use during Pregnancy (A study at Rafidia Governmental Hospital/Palestine). Faculty of Graduate Studies Prevalence and Predictors of Herb Use during Pregnancy (A study at Rafidia Governmental Hospital/Palestine) By Deema Hilmi Adawi Supervisor Dr. Rowa’Al-Ramahi Co-supervisor Dr. Nidal Jarradat This thesis is submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Graduate Studies, An-Najah National University; 2012.

Adams J, Sibbritt D, Lui CW. The use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: a longitudinal study of Australian women. Birth. 2011;38(3):200–6.

Holst L, Wright D, Haavik S, Nordeng H. The use and the user of herbal remedies during pregnancy. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(7):787–92.

Fakeye TO, Adisa R, Musa IE. Attitude and use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9(1):53.

Cuzzolin L, Zaffani S, Murgia V, Gangemi M, Meneghelli G, Chiamenti G, Benoni G. Patterns and perceptions of complementary/alternative medicine among paediatricians and patients' mothers: a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162(12):820–7.

Cuzzolin L, Benoni G. Safety Issues of Phytomedicines in Pregnancy and Paediatrics. In Herbal Drugs: Ethnomedicine to Modern Medicine, RamawatKG (ed.). Springer Verlag: Berlin-Heidelberg. 2009; 381–396.

Cuzzolin L, Francini-Pesenti F, Verlato G, Joppi M, Baldelli P, Benoni G. Use of herbal products among 392 Italian pregnant women: focus on pregnancy outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(11):1151–8.

Holst L, Wright D, Nordeng H, Haavik S. Use of herbal preparations during pregnancy: focus group discussion among expectant mothers attending a hospital antenatal clinic in Norwich, UK. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):225–9.

Kalder M, Knoblauch K, Hrgovic I, Münstedt K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy and delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(3):475–82.

Nordeng H, Bayne K, Havnen GC, Paulsen BS. Use of herbal drugs during pregnancy among 600 Norwegian women in relation to concurrent use of conventional drugs and pregnancy outcome. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(3):147–51.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by KOICA (Korea International Cooperative Agency) and Basrah Health Directorate, Iraq. We are grateful to all the participating women who took part in this study.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The data will be accessible by contacting the corresponding author of this study.

Authors’ contributions

JH and DW were responsible to the study concept and design. DW, JH, SJ and MA analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. YR, NQ and NM contributed in the designing of data collection tools and data collection. JH, DW, YR, SJ and MA critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Prior to survey, potential participants were informed the purpose of the study and that participation was voluntary. Then informed consent to participate was obtained from each of the participants in our study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was acquired from Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Research and Ethics Committees, Hanyang University (HYI-14-0007-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, J.H., Kim, YR., Ahmed, M. et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy: a cross-sectional survey on Iraqi women. BMC Complement Altern Med 16, 191 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-016-1167-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-016-1167-0