Abstract

Background

The root of Angelica dahurica Bentham et Hooker (Umbelliferae) has been used as a traditional medicine for colds, headache, dizziness, toothache, supraorbital pain, nasal congestion, acne, ulcer, carbuncle, and rheumatism in China, Japan, and Korea. Interestingly, it has been used in the treatment of vascular diseases including hypertension. The aim of this study was to provide pharmacological evidence for the anti-hypertensive effect of A. dahurica by investigating the mechanism underlying its vasorelaxant effect.

Methods

The vasorelaxant effects of a 70 % methanol extract of the A. dahurica root (ADE) on rat thoracic aorta and its underlying mechanisms were assessed. Isolated rat aortic rings were suspended in organ chambers containing 10 ml Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution and placed between 2 tungsten stirrups and connected to an isometric force transducer. Changes in tension were recorded via isometric transducers connected to a data acquisition system.

Results

ADE causes concentration-dependent relaxation in both endothelium-intact and endothelium-denuded aortic rings precontracted with phenylephrine (PE; 1 μM) or potassium (KCl; 60 mM) in K-H solution. And pre-treatment with ADE (1 mg/ml) inhibited calcium-induced vasocontraction of aortic rings induced by PE or KCl. However, ADE pre-treatment did not affect the contraction induced by PE or caffeine in Ca2+-free K-H solution.

Conclusions

These results suggested that the ADE has vasorelaxant effect and the vasorelaxant activity is mediated by endothelium-independent pathway that includes the blockade of extracellular calcium influx through the receptor-operated Ca2+ channel and voltage-dependent calcium channel pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Angelica dahurica Bentham et Hooker (Umbelliferae) is a perennial plant that grows widely in East Asia. The roots of this plant are used as a traditional medicine for colds, headache, dizziness, toothache, supraorbital pain, nasal congestion, acne, ulcer, carbuncle, and rheumatism [1, 2]. To date, the root has been reported to have antibacterial properties [3], wound healing effect [4], acetylcholinesterase inhibitory effect [5], anti-asthmatic effect [6], anti-staphylococcal effect [7], anti-acne effect [8], anti-inflammatory effect [9, 10], antitumor effects [11], protective effect against sepsis [12], and hypotensive properties [13]. Furthermore, imperatorin isolated from root of A. dahurica showed anti-cancer effect [6], anti-oxidant effect [14], hepatoprotective effect [15] and vasodilation activity [16].

Several previous studies have focused on the vascular activities of A. dahurica due to the frequent use of the herb, together with other herbs in clinical use, to relieve stagnant Qi, promote blood flow, and treat blood stasis [13, 14, 17–19]. Furthermore, imperatorin, one of major component of A. dahurica, is reported to have anti-hypertensive and vascular remodeling effects [20, 21], and vasodilation activity [22].

Recently there has been increased interest in the hypotensive effects of traditional medicines which have been used in China, Japan and Korea for several thousand years [23–26].

Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to provide pharmacologic evidence for the traditional use of A. dahurica in the treatment of vascular diseases by determining the probable mechanisms involved in its vasorelaxant effect.

Methods

Chemicals and drugs

Phenylephrine hydrochloride (PE), acetylcholine (Ach), ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), potassium chloride (KCl), calcium chloride (CaCl2), and caffeine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Barium chloride was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). All other reagents were of analytical purity.

Plant material and extraction

A. dahurica was collected from Uiseong, Gyeongbook Province, Republic of Korea in 2008. Plant identification was performed by Professor Hocheol Kim of Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea. A voucher specimen (AD001) of A. dahurica was deposited at the College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University. A crude extract was prepared by decoction of dried root and rhizome of A. dahurica (3.0 kg) in methanol (3 L) for 3 times (120 min per time). After reflux and filtration, the extract was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 70 °C and lyophilized to yield 912.0 g of crude extract. The crude extract was dissolved in Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution when applying to aortic rings in organ chamber.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

HPLC analysis was performed at room temperature at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min by a Gilson system equipped with a 234 autosampler, a UV/VIS-155 detector, and a 321 HPLC Pump (Gilson, Seoul, Korea). The injection volume was 2 μl. A LUNA 4.60 × 250 mm C18 reverse-phase column with 5-μm particles (Phenomenex, CA, USA) was used. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (A) and distilled water (B) (HPLC grade, J. T. Baker Co. LTD., USA) at the ratio of 6:4. The column eluent was monitored at 254 and 365 nm.

Animals

All animal procedures were conducted according to the animal welfare guidelines issued by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (KHUASP[SE]-09-042). Male Sprague–Dawley rats (N = 30, Narabio, Seoul, Republic of Korea) weighing 240–260 g were housed under controlled conditions (temperature, 22 ± 2 °C; lighting, 07:00–19:00 h), with food and water available ad libitum.

Experimental protocols

The method of preparation of rat aortic rings has been described previously [27]. Isolated rat aortic rings were suspended in organ chambers containing 10 ml K-H solution and placed between 2 tungsten stirrups and connected to an isometric force transducer. Changes in tension were recorded via isometric force transducers connected to a data acquisition system. Effects of a 70 % methanol extract of the A. dahurica root (ADE) on PE- and KCl-induced contraction: Endothelium-intact aortic rings were precontracted by PE (1 μM) or KCl (60 mM) in standard Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution. After a plateau was reached, cumulative doses (0.03–3.0 mg/ml) of ADE were added. The relaxant effect on the aortic rings was expressed as a percentage of contraction induced by PE or KCl.

Role of endothelium in ADE-induced relaxation: The concentration-dependent relaxant effect of ADE was studied in endothelium-intact and endothelium-denuded aortic rings precontracted by PE (1 μM) in standard K-H solution. After contraction with PE, Ach (10 μM) was added in order to confirm the absence or presence of endothelium. After washing, rings were contracted with PE (1 μM). After contraction with PE, cumulative doses (0.03–3.0 mg/ml) of ADE were added. In the previous screening study, ADE did not relax PE-precontracted aortic rings at dose of 0.001, 0.003, and 0.01 mg/ml. Therefore, vasorelaxant effects of ADE was observed at the dose of 0.03 mg/ml. The relaxant effect on the aortic rings was expressed as a percentage of the contraction induced by PE.

Effects of ADE on extracellular Ca2+-induced contraction: The vasorelaxant activities of ADE (1 mg/ml) on the receptor-operated Ca2+ channel (ROCC) and voltage-dependent calcium channel (VDCC) in Ca2+-free K-H solution were investigated in the same manner as we previously described [27].

Effects of ADE on intracellular Ca2+ release: In order to investigate the effects of ADE on intracellular Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)-induced contraction via specific inositol triphosphate receptor (IP3R) channels or ryanodine receptor (RyR) channels, the contractile activities of PE (1 μM) or caffeine (5 mM) were investigated on endothelium-denuded aortic rings after 10 min of pretreatment with ADE (1 mg/ml) in Ca2+-free K-H solution.

Data analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 10.0) statistical analysis software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Vasorelaxant effects of ADE

ADE (0.03–3.0 mg/ml) relaxed PE-precontracted (1 μM) endothelium-intact aortic rings in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1a, b and c). ADE (0.03–1.0 mg/ml) also relaxed KCl-precontracted (60 mM) endothelium-intact aortic rings in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1d, e and f).

Vasorelaxant effect of a 70 % methanol extract of Angelica dahurica root (ADE) on phenylephrine (PE)-precontracted (a, b, and c) or KCl-precontracted (d, e, and f) rat aortic rings. Representative traces show the control group (a and d) and the ADE-treated group (b and e). Control groups were treated with the same volume of Krebs-Henseleit solution without ADE. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6–8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control

Role of endothelium in ADE-induced relaxation

ADE showed a concentration-dependent relaxation effect in both endothelium-intact and endothelium-denuded aortic rings after precontraction by PE (1 μM). However, the functional removal of endothelium did not modify ADE-induced relaxation in PE-precontracted rat thoracic aorta rings (Fig. 2).

Vasorelaxant effect of a 70 % methanol extract of Angelica dahurica root (ADE) on phenylephrine (PE)-precontracted (1 μM) rat aortic rings with (E+) (a) or without (E-) (b) endothelium. PE-induced contraction of endothelium-intact aortic ring almost relaxed to baseline after acetylcholine treatment (Ach, 10 μM) (a). PE-induced contraction of endothelium-denuded aortic ring remained unaffected after acetylcholine treatment (b). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8) (c)

Effects of ADE on Extracellular Ca2+-induced Contraction

In order to investigate the effects of ADE on the ROCC and VDCC pathways, PE (1 μM) and KCl (60 mM) were applied to induce stable contraction, respectively. Pre-treatment with ADE (1 mg/ml) significantly inhibited the contraction induced by extracellular CaCl2 (0.3–10 mM) compared to the control group (Fig. 3).

Inhibitory effects of a 70 % methanol extract of A. dahurica root (ADE, 1 mg/ml) on extracellular Ca2+-induced (0.3–10 mM) contraction in endothelium-denuded rat aortic rings precontracted by phenylephrine (PE, 1 μM) (a, b, and c) or KCl (60 mM) (d, e, and f) in Ca2+-free solution. Representative traces show the control group (a and d) and the ADE-treated group (b and e). Control groups were not pre-incubated with ADE. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4–8). *P < 0.01, **P < 0.01 vs. control

Effect of ADE on SR calcium release induced by PE or caffeine

In Ca2+-free K-H solution, pre-treatment with ADE (1 mg/ml) for 10 min did not inhibit PE-induced (1 μM) contraction or caffeine-induced (5 mM) contraction (Fig. 4).

Inhibitory effect of a 70 % methanol extract of A. dahurica root (ADE, 1 mg/ml) on contraction via SR calcium release (the IP3 pathway) by PE (1 μM) in Ca2+-free solution (a, b, and c) and on contraction via sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release (the RyR pathway) by caffeine (5 mM) (d, e, and f) in Ca2+-free solution. Representative traces show the control group (a and d) and the ADE-treated group (b and e). Control groups were not pre-incubated with ADE. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8)

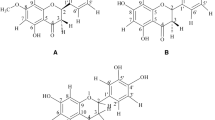

HPLC analysis of ADE

Four standard components of A. dahurica, oxypeucedanin hydrate, oxypeucedanin, imperatorin, and isoimperatorin were found in ADE (Fig. 5). And the contents of oxypeucedanin hydrate, oxypecedanin, imperatorin, and isoimperatorin in ADE were calculated to 0.23, 5.9, 0.63, 0.43 %, respectively.

Discussion

Vascular tone is the major factor determining the blood flow through the circulatory system. Regulation of the vasoactivity of vascular smooth muscle is dependent on a complex interplay of vasodilatory and vasoconstrictory actions by circulating hormones, neurotransmitters, and endothelium-derived factors [28]. The vasorelaxant effect is usually classified as endothelium dependent or independent depending on endothelial function. The endothelium regulates vascular smooth muscle tone through the secretion of vasorelaxant substances such as nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor [29], as well as through endothelium-derived contracting factors such as endothelins, angiotensin II, cyclooxygenase-derived prostanoids, and superoxide anions [30]. In the present study, ADE evoked a concentration-dependent relaxation of aortic rings precontracted by the application of PE (1 μM) or KCl (60 mM). The removal of functional endothelium did not change these responses. These results indicated that the vasorelaxant mechanism of ADE may not be regulated by endothelium-dependent factors.

Vascular smooth muscle contraction generally occurs through pharmacomechanical or electromechanical coupling [31]. Pharmacomechanical coupling involves the activation of cell-surface receptors, such as the α-adrenergic receptor, to increase extracellular Ca2+ influx through the ROCC or the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. In contrast, electromechanical coupling involves the depolarization of the cell membrane to increase extracellular Ca2+ influx through the VDCC [32]. PE, an alpha-adrenergic agonist, contracts smooth muscle cells through the extracellular Ca2+ influx in ROCCs and through the release of internal Ca2+ from specific IP3R channels in the SR membrane [33, 34]. KCl contracts smooth muscle cells mainly by the extracellular Ca2+ influx that occurs with the depolarization of the cell membrane and subsequent opening of VDCCs [35]. Caffeine contracts smooth muscle cells by internal calcium release from RyR channels in the SR membrane [36]. Therefore, the vasorelaxant effects of ADE were investigated using vasoconstrictors such as PE, KCl, and caffeine on the following physiologic processes: extracellular Ca2+ influx via the ROCC or VDCC pathways and intracellular Ca2+ release via IP3R or RyR channels.

In the present study, ADE (1 mg/ml) inhibited the vasocontraction induced by Ca2+ supplementation in rat aortic rings that were precontracted with PE (1 μM) in a Ca2+-free K-H solution. This result suggests that ADE can inhibit the vasocontraction induced by extracellular Ca2+ entry via the ROCC pathway. And ADE (1 mg/ml) also inhibited the vasocontraction induced by Ca2+ supplementation in the aortic rings precontracted with KCl (60 mM) in a Ca2+-free K-H solution. This result suggests that ADE may also inhibit the vasocontraction induced by extracellular Ca2+ entry via the VDCC pathway.

In a Ca2+ free K-H solution, PE-induced contraction is only mediated by the IP3 pathway [33]. In the present study, a 10-min pretreatment with ADE (1 mg/ml) did not inhibit PE-induced (1 μM) contraction. This result suggests that ADE-evoked vasorelaxation may not be related to internal calcium release from specific IP3R channels in the SR.

In the present study, a 10-min pretreatment with ADE (1 mg/ml) did not inhibit caffeine-induced (5 mM) vasoconstriction. This result suggests that ADE-evoked vasorelaxation also does not affect internal calcium release from RyR channels in the SR.

In this study, 4–8 rat aortic rings were used in the control and experimental groups. This number of aortic rings could be considered not statistically significant because 4 more aortic rings could be isolated from one rat. In the present study, we isolated 4 aortic rings from one rat and used 2 rings as the control group and 2 rings as the experimental group. In Fig. 3, the control group comprised of 4 rings, while the ADE-treated group comprised of 8. In other words, 2 rats were used as the control group and 3 rats were used in the experimental group. We conducted various experiments and found that the contractions in the control group were not different from our previous experiments and there are little variations. Therefore, we used only 2 rats (4 rings) in the control group. In the in vivo experiment, many variations were observed in individual animals. However, in ex vivo experiments using aortic rings, there are little variations in individual animals. In Korea, minimum use of animals is recommended for animal welfare. We agree with your comments that more number of rings could be statistically significant. However, our experiments are ex vivo experiments using isolated rat aortic rings, and we believe that our results have statistical significance.

Oxypeucedanin, oxypeucedanin hydrate, imperatorin, and isoimperatorin are well known components of A. dahurica root [37–40]. In the present study, these four components were also found in ADE and the contents were calculated as 5.9, 0.23, 0.63, and 0.43 %, respectively. Imperatorin is a well-known anti-hypertensive compound [20–22]. In addition, Bertin et al. showed that atropine and L-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester did not alter imperatorin-induced relaxation in rat aorta [21]. In the present study, ADE also relaxed the rat aortic rings pre-contracted with PE or KCl in an endothelium-independent manner. Therefore, the vasorelaxant effects of ADE might be partly attributable to imperatorin. However, Nie et al. suggested that imperatorin relaxed the mouse thoracic aorta pre-contracted with PE in an endothelium dependent manner [16]. These different results might be attributed to the use of mouse thoracic aorta. Although oxypeucedanin was the most abundant component in ADE, its vasorelaxant or anti-hypertensive activities have not been reported yet. Oxypeucedanin hydrate and isoimperatorin also have not been reported to have vasorelaxant activities or anti-hypertensive activities. Therefore, further phytochemical and pharmacological studies of ADE are needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that ADE has vasorelaxant activity and the vasorelaxant activity of ADE is mediated by endothelium-independent pathway that includes the blockade of extracellular calcium influx through the ROCC and VDCC pathways. In addition, intracellular calcium-release pathways through the IP3R and RyR channels were not involved in the vasorelaxant effect of ADE.

Statement of ethics

This study was submitted to, and approved by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval number: KHUASP[SE]-09-042).

References

Liao ZG, Liang XL, Zhu JY, Zhao GW, Yang M, Wang GF, et al. Correlation between synergistic action of Radix Angelica dahurica extracts on analgesic effects of corydalis alkaloid and plasma concentration of dl-THP. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129(1):115–20.

State Pharmacopoeia Committee. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2010.

Kwon YS, Kobayashi A, Kajiyama S, Kawazu K, Kanzaki H, Kim CM. Antimicrobial constituents of Angelica dahurica roots. Phytochemistry. 1997;44(5):887–9.

Bai XZ, Hu DH, Wang YC, Liu JQ, Shi JH, Tang CW. Effects of Angelica dahurica extract on biological behavior of dermal fibroblasts. Chinese Journal of Surgery. 2012;50(4):357–60.

Kim DK, Lim JP, Yang JH, Eom DO, Eun JS, Leem KH. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from the roots of Angelica dahurica. Arch Pharm Res. 2002;25(6):856–9.

Lee MY, Seo CS, Lee JA, Lee NH, Kim JH, Ha H, et al. Anti-asthmatic effects of Angelica dahurica against ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation via upregulation of heme oxygenase-1. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(4):829–37.

Lechner D, Stavri M, Oluwatuyi M, Pereda-Miranda R, Gibbons S. The anti-staphylococcal activity of Angelica dahurica (Bai Zhi). Phytochemistry. 2004;65(3):331–5.

Nam C, Kim S, Sim Y, Chang I. Anti-acne effects of Oriental herb extracts: a novel screening method to select anti-acne agents. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2003;16(2):84–90.

Kim Y, So HS, Youn MJ, Kim ES, Song MS, Chai KY, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of So-Pung-Tang, a Korean traditional prescription for cerebral infarction patients. J Ethnopharmaco. 2007;114(3):425–31.

Jeong KT, Kim SG, Lee J, Park YN, Park HH, Park NY, et al. Anti-allergic effect of a Korean traditional medicine, Biyeom-Tang on mast cells and allergic rhinitis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:54.

Kim YK, Kim YS, Ryu SY. Antiproliferative effect of furanocoumarins from the root of Angelica dahurica on cultured human tumor cell lines. Phytother Res. 2007;21(3):288–90.

Song DK, Kim JY, Li G, Lee KS, Seo CS, Yan JJ, et al. Agents protecting against sepsis from the roots of Angelica dahurica. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(2):380–2.

WU YY JIANGGH, MA YY, GAO Y. Research Advancement on Pharmacological Effect of Radix Angelicae Dahuricae. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research. 2009;3:057.

Cao Y, Zhang Y, Wang N, He L. Antioxidant effect of imperatorin from Angelica dahurica in hypertension via inhibiting NADPH oxidase activation and MAPK pathway. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(8):527–36.

Oh H, Lee HS, Kim T, Chai KY, Chung HT, Kwon TO, et al. Furocoumarins from Angelica dahurica with hepatoprotective activity on tacrine-induced cytotoxicity in Hep G2 cells. Planta Med. 2002;68(5):463–4.

Nie H, Meng LZ, Zhou JY, Fan XF, Luo Y, Zhang GW. Imperatorin is responsible for the vasodilatation activity of Angelica dahurica var. Formosana regulated by nitric oxide in an endothelium-dependent manner. Chin J Integr Med. 2009;15(6):442–7.

Wang MY, Jia MR. Herbological study on the functions of radix Angelicae dahuricae. Shanghai Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2004;38:56–7.

Li L, Yang HJ, Xiao YQ, Zhang C. Effect of principal constituents and their combination of chuanxiong fangfeng baizhi formula on rat isolated thoracic aorta. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2009;32:550–6.

Wang S, Hu Y, Tan W, Wu X, Chen R, Cao J, et al. Compatibility art of traditional Chinese medicine: from the perspective of herb pairs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;143(2):412–23.

Zhou N, Wang T, Song J, He H, He J, He L. Antihypertensive and vascular remodelling effects of the imperatorin derivative OW1 in renovascular hypertension rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41(8):571–8.

Cao YJ, He X, Wang N, He LC. Effects of imperatorin, the active component from Radix Angelicae (Baizhi), on the blood pressure and oxidative stress in 2 K,1C hypertensive rats. Phytomedicine. 2013;20(12):1048–54.

Bertin R, Chen Z, Martinez-Vazquez M, Garcia-Argaez A, Froldi G. Vasodilation and radical-scavenging activity of imperatorin and selected coumarinic and flavonoid compounds from genus Casimiroa. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(5):586–94.

Wang J, Xiong X. Evidence-based chinese medicine for hypertension. Evid Bbased Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:978398.

Xiong X, Yang X, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Wang P, Wang J. Chinese herbal formulas for treating hypertension in traditional Chinese medicine: perspective of modern science. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(7):570–9.

hih HC, Lee TH, Chen SC, Li CY, Shibuya T. Anti-hypertension effects of traditional Chinese medicine ju-ling-tang on renal hypertensive rats. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33(6):913–21.

Tsai DS, Chang YS, Li TC, Peng WH. Prescription pattern of Chinese herbal products for hypertension in Taiwan: a population-based study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155(3):1534–40.

Lee K, Ham I, Yang G, Lee M, Bu Y, Kim H, et al. Vasorelaxant effect of Prunus yedoensis bark. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:31.

Jackson WF. Ion channels and vascular tone. Hypertension. 2000;35(1 Pt 2):173–8.

Luksha L, Agewall S, Kublickiene K. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in vascular physiology and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202(2):330–44.

Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S. Endothelium-dependent contractions and endothelial dysfunction in human hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(4):527–36.

Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Electromechanical and pharmacomechanical coupling in vascular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968;159(1):129–45.

Ogut O, Brozovich FV. Regulation of force in vascular smooth muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(4):347–55.

McFadzean I, Gibson A. The developing relationship between receptor-operated and store-operated calcium channels in smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135(1):1–13.

Janbaz KH, Arif J, Saqib F, Imran I, Ashraf M, Zia-Ul-Haq M, et al. In-vitro and in-vivo validation of ethnopharmacological uses of methanol extract of Isodon rugosus Wall. ex Benth. (Lamiaceae). BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:71.

Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(4 Pt 1):799–822.

Lompre AM. Sarcoplasmic reticulum in vascular cells in hypertension and during proliferation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26(7):553–7.

Fan G, Deng R, Zhou L, Meng X, Kuang T, Lai X, et al. Development of a rapid resolution liquid chromatographic method combined with chemometrics for quality control of Angelicae dahuricae radix. Phytochem Anal. 2012;23(4):299–307.

Wang J, Chen Z, Wu Y, Fan G. Fast determination of active components in Angelica dahurica extract using capillary electrochromatography with methacrylate ester-based monolithic columns. Chinese journal of chromatography. 2010;28(3):240–6.

Kang SW, Kim CY, Song DG, Pan CH, Cha KH, Lee DU, et al. Rapid identification of furanocoumarins in Angelica dahurica using the online LC-MMR-MS and their nitric oxide inhibitory activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Phytochem Anal. 2010;21(4):322–7.

Wei Y, Ito Y. Preparative isolation of imperatorin, oxypeucedanin and isoimperatorin from traditional Chinese herb "bai zhi"Angelica dahurica (Fisch. ex Hoffm) Benth. et Hook using multidimensional high-speed counter-current chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1115(1–2):112–7.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the High Value-added Food Technology Development Program, Korea Institute of Planning & Evolution for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (314071-03-1-HD020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KL and MS performed the animal experiments. IH performed the HPLC analysis. KL and MS participated in the writing of the manuscript. HC conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, K., Shin, M.S., Ham, I. et al. Investigation of the mechanisms of Angelica dahurica root extract-induced vasorelaxation in isolated rat aortic rings. BMC Complement Altern Med 15, 395 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0889-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0889-8