Abstract

Background

Males dominate in tobacco usage, as well as in tobacco research, knowing that women face more severe health consequences. There is a specific lack of information on epidemiological statistics, risks, and the level of knowledge among women regarding tobacco. This study examines the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS)-India dataset to estimate female tobacco usage and assess socio-economic variations in tobacco consumption, awareness regarding the adverse effects of tobacco, noticing pack health warnings (PHW), and intention to quit tobacco use well as factors influencing these domains.

Methods

Using a geographically clustered multistage sampling method, the nationally representative GATS II (2016–17) interviewed 40,265 female respondents aged 15 years and above from all Indian states and union territories. Standard operational definitions were used to estimate the primary independent variables (community, individual, and household categories) and dependent variables like awareness regarding the adverse effects of tobacco, noticing pack health warning (PHW), and intention to quit tobacco. Sampling weights were adjusted while performing the analysis. Bivariate and multivariable analysis were used to generate the estimates.

Results

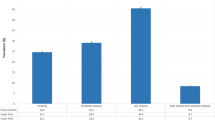

Of the total female respondents, 84.2% were never-users, 13.3% ever consumed Smokeless Tobacco (SLT) products, 1.8% ever smoked tobacco, and 0.8% were dual users once in their lives. Around 16% of the women had exposure to Second Hand Smoke (SHS) either at their homes, workplaces or in public places. Overall, maximum awareness was seen among non-smoker females (64.7%) and dual users (64.7%), followed by women exposed to SHS, SLT users, and smokers. PHW was noticed more by the bidi smokers, followed by SLT users and cigarette smokers. Factors that positively affected intention to quit smoking included younger age, secondary school education, self-employed status, the habit of buying packed cigarettes/bidi, believing that smoking causes serious illness, and attempted quitting in the last 12 months.

Conclusion

A high proportion of women consume tobacco which is significantly influenced by socio-demographic factors. Tobacco regulators should be especially concerned about women as the tobacco marketing experts target them. Mobilizing self-help groups and organizations working for women and children could assist broader campaigns to generate awareness and motivate quitting attempts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overall global tobacco use has decreased over the last two decades, from 1.397 billion in 2000 to 1.337 billion users in 2018. The age-standardized tobacco use prevalence rates are also declining in all World Health Organization (WHO) regions. [1]. The tobacco industry foresaw the declining trend in its very initial stages. Hence, they started shifting their targets to find newer business avenues in the Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC), making them more vulnerable to the tobacco epidemic. [2,3,4,5]. The exaggerated efforts by the tobacco industries increased the participation and indulgence of both men and women from LMICs in consuming tobacco [6]. Consequently, a state of an epidemic of tobacco-related diseases has been created in these countries, where tobacco usage is rapidly becoming a pertinent public health issue. Furthermore, the WHO Southeast Asian Region has the highest tobacco consumption rates, with an estimated (2018) 29.1% of adults aged 15 years and older using tobacco in any form. [1, 7, 8].

Until 2016, India was the world’s 2nd largest tobacco consumer, trailing only China [9]. Similar to global patterns, the tobacco epidemic in India is gradually declining. The most recent round of the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) conducted between 2016 and 17 showed a 6% decrease in tobacco use in Indian adults(> 15 years). Compared with the previous round, the overall tobacco usage in India has decreased relatively by around 11.5% and 30% in males and females, respectively [10]. However, the preliminary reports from the fifth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) (2019-20) also confirm the declining trends and corroborate with the GATS-2 to depict that the declining trends are not seen all over the country [11]. Tobacco usage has decreased among men in most Indian states, except Sikkim, Goa, Bihar, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, and Mizoram. The prevalence of women’s tobacco consumption has also decreased in all states except Mizoram and Sikkim [11]. These disparities suggest that tobacco control programs require more focused interventions for vulnerable groups of people. Furthermore, the emphasis on men portrays gender bias and the inequality that underpins many tobacco control programs [12, 13]. Over the last few decades, policymakers and implementers have become increasingly concerned about the alarming rise in tobacco use among women in developed and developing nations [14]. This is because an increase in the number of female tobacco users will have a significant negative impact on household finances and family health [15].

Tobacco exerts strong adverse effects on women’s health due to premature menopause attributed to its anti-estrogen effect. While tobacco reduces the risk of endometrial cancer as per Felix et al. (2014) [16]. , it increases the risk for premature menopause, which in turn enhances the risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporotic fractures [17]. Also, tobacco usage is causative of several gynecological problems, including cancers. There is a direct association between tobacco use in reproductive age groups and breast cancer, especially if smoking begins while the woman is nulliparous [18]. Tobacco exacerbates cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and has been related to cervical squamous cell carcinoma in women seropositive for the Human Papillomavirus16 and 18 [19].

The high percentage of non-smoking women makes them an attractive target for the tobacco industry. Their efforts to promote tobacco usage are supported by the dearth of adequate awareness regarding the adverse effects of tobacco, prevalent myths around smoke, and SLT products. Unless sustained and efficient measures are implemented, the prevalence of female tobacco use is expected to rise. Article 4 of the World Health Organization- Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC) Guiding Principles raised concerns about gender disparity in tobacco control efforts. It emphasized the “need for taking measures to address gender-specific risks when developing tobacco control strategies.”[20].

There is a specific lack of information on epidemiological statistics, risks, and the level of knowledge among women regarding tobacco. Robust evidence will effectively guide tobacco control policies, resulting in substantial gains in public health and reduced morbidity and mortality, especially when viewed through a gender parity lens. Tobacco usage trends, in this regard, are an essential source of insight at the national and sub-national levels for monitoring the effectiveness of existing policy initiatives and determining future directions. Over the last decade, GATS-India has assessed tobacco prevalence and pattern of use at various points in time. This secondary data analysis attempts to review GATS datasets to estimate the prevalence of tobacco use among females. The study’s specific objectives were to comprehensively understand the socio-economic variations in tobacco usage, their awareness of the harmful effects of tobacco, noticing the PHW, their intention to quit tobacco usage, and factors influencing these domains.

Methodology

Source of data

We used data from the second wave of GATS-India (2016-17) [9]. It is a cross-sectional national survey conducted by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences designated by MoHFW, Government of India. GATS-2 included all states of India. This survey followed a standard protocol for the study design, data collection, and study tool development. GATS-2 addressed tobacco usage (smoking and SLT), SHS exposure, cessation, economics, media messages, knowledge, attitude, and perceptions of tobacco use.

Sample selection

In total, 40,265 female respondents (≥ 15 years) were included in the GATS-2 final sample (Fig. 1). The Operational definitions of the tobacco consumption variables used in the analysis like ‘Ever tobacco users,’ ‘Smoking tobacco (ever) users,’ ‘SLT users (ever users),’‘ Dual users,’ and ‘Never-users’ were defined as per the standard GATS methodology [21]. Further, ‘Second-hand smoking’ was determined based on our previous methods. [22].

Study variables

Dependent variables

-

Comprehensive awareness about the adverse effects of tobacco: Comprehensive awareness of the respondent was defined as the respondent being aware of all of the severe illnesses caused by tobacco including stroke, heart attack, lung cancer, chronic cough/Tuberculosis, and SLT causes any severe illnesses or oral cancer, dental diseases or that SLT during pregnancy causes harm to the fetus. The details about this variable are described in detail elsewhere [23].

-

Noticed PHW: Outcome variables for noticing PHW and thought of quitting because of PHW were defined separately for smokers, bidi smokers, and SLT users. The variable was derived using the previously published methodology [24].

-

Intention to quit/Thought of quitting tobacco usage: The variable “thinking to quit smoking because of PHW” among respondents who consumed smoking tobacco or SLT was derived from previously published literature [24].

Independent variables

A variety of factors influence tobacco consumption. Independent variables were selected following a rigorous literature review, and the variables that significantly affected the dependent variables were included in the study. These variables were classified at community, household, and individual levels.

Regions and residence (urban/rural) were variables included in the community category. India was divided into six regions based on geographical location and cultural factors per the GATS India protocols: North, Central, West, South, East, and North East.

The household category variables included wealth index quintiles, caste (Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes, and Others), and religion (Hindu, Muslim, and Others). The variable “wealth quintile” was created using a summative score of inverse weighted proportions of possession of the following assets: electricity; refrigerator; washing machine; air conditioner; electric fan; internet connection; computer/laptop; fixed telephone; cell phone; and radio. The summative score was then divided into quintiles to obtain wealth categories (lowest, lower, middle, higher, and highest quintiles), used as a proxy for wealth or socio-economic status [25, 26].

Individual variables included age in completed years (15–24/25–44/45–64 and 65 and above), sex (male/female), level of education (no education, primary, secondary, and higher), type of occupation (government and non-government, self-employed, student, homemaker, and retired/unemployed), currently pregnant and awareness among the respondents.

Statistical analysis

We used STATA 13 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 to calculate our estimates, and it was represented as a weighted percentage with a 95% confidence interval. To estimate the relationship between tobacco usage (smoked, smokeless, and dual usage), socio-demographic characteristics, awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco use, noticing the PHW, and intentions to quit tobacco, the chi-square test was used to examine the associations. The unadjusted odds ratio was calculated using univariate logistic regression. Independent variables with p-values < 0.02 were considered for the multivariable logistic regression model, and the backward likelihood ratio method was used to determine the best fit model. Models were created using the complex sample analysis technique after applying sampling weights and adjusting for multistage sampling designs. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of < 0.05.

Results

A total of 40,625 women ≥ 15 years of age responded during the GATS-2. Amongst them, 84.2%were never-users, 13.3% ever consumed SLT products, 1.8% ever smoked tobacco, while 0.8% were dual users once in their lives. About 16.6% of the women were exposed to SHS in their homes, workplace, or public places.

Table 1 depicts the variations in the prevalence of tobacco usage amongst women as per the various socio-demographic indicators. There was an increase in the prevalence of tobacco usage with age, and it was highest in separated/divorced/widowed women from rural areas. SLT and dual usage were highest among uneducated women, and smoked tobacco was highest among women educated up to secondary school. Women from the North-eastern part of the country had the highest amount of SLT and dual tobacco users, while women from north India preferred smoking over other types of usage. We observed that women from the poorest sections of the society (first quintile) had the highest prevalence of SLT consumption, while the fourth quintile showed maximum usage of smoked tobacco or were dual users. Prevalence of SLT, smoked and dual use of tobacco was also higher amongst the women and low levels of awareness. The exposure to the SHS at any place was significantly more amongst the youngest age groups, unmarried, educated women from urban areas of North India, who were from the richest sections of society. Pregnant women and women with high awareness showed more exposure to SHS.

Table 2 depicts the socio-demographic variations in awareness levels. Overall, females who never consumed tobacco (Never-users) (64.7%) and dual users (64.7%) showed maximum awareness, followed by women exposed to SHS, SLT users, and smokers. Upon further disaggregation, middle-aged and married smokers, youngest and unmarried SLT users, dual users, and women exposed to SHS showed maximum awareness. Awareness increased with education and was high in urban areas (except in the cases of smokers, where women with more years of education and urban regions showed minimum knowledge). Minimum awareness was seen in smokers, SH smokers from central India, SLT users from North India, and dual users from South India. Women with positive intentions to quit had better knowledge, except for dual users.

We then compared the effects of noticing the PHW on thoughts about quitting amongst the different types of tobacco users (Table 3). PHW was noticed more by the bidi smokers, followed by SLT users and cigarette smokers. PHW was noticed more in younger age groups, educated women from urban areas, and in the highest socio-economic quintile of society. The proportion of females who had thought about quitting tobacco usage because of PHW was highest amongst cigarettes, followed by bidi users, and was minimum for SLT users. Among cigarette smokers, thinking about quitting was most common in women between 45 and 59 years of age, from rural areas, with no formal school, and belonging to middle-class families. The highest proportion of bidi smoking women who thought about quitting was seen in the youngest age groups, educated up to primary school and belonging to the poorest quintile. Nearly half of the women (45.6%) thought about giving up SLT usage due to PHW. These women belonged to middle age groups, from urban areas, and were educated.

Factors associated with improved awareness, observance of the PHW, and intentions to quit smoking for smokers and SLT users are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Multivariable binary logistic regression showed that the chances of having better awareness amongst the smoker women of middle ages (45–59 years), residing in urban areas, have received higher education, or belong to the poorest sections of society, were buying packed cigarettes, and believing that tobacco causes serious illness, while occupation, current pregnancy status, age of smoking initiation, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day, and time of first smoking upon waking up were observed to be non-significant in univariate logistic analysis and were not included in the final multivariable logistic model.

Univariate analysis showed the effect of middle age, residential status, better education, average smoking per day, time of first smoking upon waking up, buying packed cigarettes/beedi, believing that tobacco causes serious illness, and making smoking quit attempts in the last 12 months on increased chances of noticing PHW. However, multivariable analysis showed only the effect of the previous three variables described above. There were higher odds of noticing PHW in unmarried smoker women, who were > 60 years of age, educated up to primary school, from urban areas, preferred to buy packed cigarette/bidi, believed that smoking causes serious illness, and those who attempted to quit smoking in last 12 months. Factors that positively affected intention to quit smoking included younger age, secondary school education, self-employed status, buying packed cigarettes/bidi, believing that smoking causes serious illness, and attempted quitting in the last 12 months.

Similarly, factors affecting awareness, noticing the PHW, and intention to quit among SLT users were assessed (Table 5). The odds of having better awareness and noticing the PHW among SLT users were better for unmarried females, urban residents with more years of education, higher socio-economic status, single-use pouch, and lesser addiction. However, the intention to quit SLT was affected by only more years of education and lower-middle-class status.

Discussion

The tobacco epidemic is swiftly claiming the lives of women and children. Though women’s tobacco use has declined in India, according to the GATS-2 data, the difference between men’s and women’s usage rates has remained nearly unchanged. Women bear a significantly more significant burden of tobacco-related disease and mortality. The tobacco industry has been at the forefront of the tobacco epidemic. In response to the substantial decline in tobacco consumption in Western countries over the last two decades, the tobacco industry has responded by focusing on women in LMIC as new potential customers. [27,28,29].

Our study found a high prevalence of SLT, SHS, and dual tobacco use among women. This load appears low when comparing male and female genders due to the former’s significantly larger consumption. As per the GATS atlas, 2015 tobacco use among Indian women as per round 1 (2010) was estimated to be 20%, placing them seventh out of 22 countries surveyed by GATS [30]. The prevalence decreased further as per the second round of GATS to 14.2% [31]. There is an overwhelming usage of SLT by Indian women (12.3%). In India, dual tobacco usage at 0.5% among women is high (or 5.3% of all current female tobacco users aged 15 and above) compared to other south-east Asian countries like Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia [30, 31]. Because of under-reporting or the dearth of reliable data, low rates of female tobacco usage in Asian and African countries are likely higher than estimated [32, 33]. For instance, it was recently reported that the rate of cotinine-verified smokers in Korea was 8% higher than the rate of self-reported smokers [32].

We observed that the prevalence of ever-usage varied significantly with the socio-demographic characteristics like age of women, marital status, education, residential status, wealth quintiles, etc. Tobacco usage initiation in young women has been promoted by tobacco marketing, and some of the first advertisements posed cigarettes as a means of weight loss [34]. Currently, markets are inundated with advertisements that associate tobacco use with social desirability and women’s empowerment. It’s worth noting that, while men adopt smoking for the euphoric effects of nicotine, women smoke to experience just the smoke-related stimuli [35].

In our study, SLT usage was higher amongst the poorest quintiles, while smoking and dual-use were more common in affluent sections. This is incoherence to a multi-country analysis as per which, 90% of SLT burden is concentrated in LMICs, specifically among the poorest ones [36]. This is because the burden of SLT has not received adequate attention on a global scale. Taxation on SLT products is typically lower compared to cigarettes. This has eventually increased the acceptability of SLT due to enhanced affordability, and consumption dynamics are shifting from smoked to SLT forms [37, 38]. evidence suggests that implementing increased taxation on raw tobacco and SLT products is an apposite tool for reducing SLT use by striking the affordability component of the user behavior [39]. Though Indian women prefer smoking less, there is substantial evidence of a high propensity for SLT use [40]. Previous research has linked SLT used to poor oral health and perinatal morbidities, such as premature birth, low birth weight, and birth length [41,42,43]. Also, these consequences are dose-responsive [44]. Indian women generally support using SLT to improve oral health and as a treatment for gastric problems, apart from enhancing companionship through shared use and a stress remedy [45]. Poor women working as laborers consume SLT to increase energy for heavy work and suppress hunger [42]. On the other hand, pregnant women begin using SLT because of a myth that chewing tobacco can help maintain the teeth and gums strength during pregnancy [45].

We observed that age, education, and wealth status impacted women’s awareness of the harmful effects of tobacco. This is consistent with previous evidence, which shows that education and income are related to knowledge about the detrimental effects of tobacco on women’s health [46,47,48,49]. There is an unending list of harmful effects of tobacco usage on women. The risk of developing COPD and its variants like chronic bronchitis or emphysema, consequently premature death, is higher in women smokers (approximately 22 times more than non-smokers) [50]. They are more likely to develop cancers of the oral cavity, esophagus, pancreas, kidney, bladder, and uterine cervix. They also have a twofold higher risk of developing coronary heart disease. Postmenopausal women smokers have decreased bone mineral density and higher chances of hip fracture, unlike non-smokers women [51]. Smoking also causes premature aging due to skin wrinkling [52].

We observed that the PHW labels were noticed maximum on Bidi packings, followed by SLT and cigarettes and that too in younger literate females from urban areas. However, there were higher odds of noticing if the women bought packed tobacco or had strong knowledge regarding the harmful effects of tobacco. According to previous studies in India, only a small percentage of cigarette packs and an even lower proportion of SLT products represented compliant PHWs [53]. . This initial bottleneck is particularly problematic in delivering the desired effect of PHW amongst the users from different areas of the country and with varied socio-demographic characteristics. However, women perceive PHW as more aversive than men and smokers, and women with lower education perceive them as more aversive than non-smokers and respondents with higher education [54]. There is strong evidence from previous analysis that supports the effectiveness of the PHW in influencing quit intentions, increased concerns about the adverse effects, and adoption of the sedation behavior [54].

We observed that Quit attempts were significantly affected by the PHW. According to GATS, cross-country variations in women’s quitting intentions can range between 33.8–82.8% [30]. A study of stress responses and cravings among male and female smokers attempting to quit discovered a lower level of cortisol - a stress hormone- responsible for the relapse in men during abstinence [55]. On the contrary, women’s cortisol levels increase and favor relapse [56]. Other research discovered that smoking alternative forms of nicotine cigarettes during abstinence could exacerbate the withdrawal symptoms and have more pronounced mood effects in men than in women. Women experience a similar level of stimuli from cigarettes that may or may not have nicotine, implying a less substantial role of the chemical as a predictor of smoking than men [57]. Previous studies that have analyzed quit attempts observed that women were 30% less likely to have successful quit attempts [58]. This was explained by the concerns of possible weight gain in the post-cessation period, which may not be accurate for women with less education and low awareness about the effect of tobacco on women’s weight [59]. However, a medical practitioner’s advice play a significant role in successful cessation [60]. Therefore, it is pertinent for doctors to counsel their female clients about the adverse effects of tobacco usage regardless of their specialty.

To conclude, it should be stressed that to achieve the UN target of a 30% reduction in tobacco use by 2025, greater attention to the burden of SLT use is required, particularly in LMICs, to implement evidence-based tobacco control strategies [61]. Tobacco regulators are particularly concerned about women because they are a current target of tobacco advertisements and promotion. The interventions on raising awareness and helping women tobacco users quit must be strategized according to the socio-demographic stratum, given the sociocultural diversification of India. Besides, a strict monitoring mechanism of OTT platforms and social media must be in place to check surrogate advertisements and glamorization of tobacco use. Mobilization of self-help groups, civil society advocates, and organizations working for women and children could assist and support broader campaigns to generate awareness and motivate users to quit. The tobacco control policies and intervention services for hard-to-reach areas and particular subgroups among women and youth should cater to their socio-demographic characteristics to pitch broader dissemination. The involvement of more female and youth ambassadors in tobacco control could set in a real-time advocacy mechanism to steer the tobacco-free movement in the country. In addition, there is a pressing need to implement an institutional mechanism rooted in systems thinking approach to support and achieve Sustainable Development Goals.

Data availability

The dataset is available at Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Global Adult Tobacco Survey- 2(2016–2017), India.

(https://nccd.cdc.gov/GTSSDataSurveyResources/Ancillary/DataReports.aspx?CAID=2) and data were retrieved using standard protocols.

Abbreviations

- LMIC:

-

Low Middle-Income Countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- GATS:

-

Global Adult Tobacco Survey

- NFHS:

-

National Family Health Survey

- SLT:

-

Smokeless Tobacco

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- MoHFW:

-

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

- PHW:

-

Pack Health Warning

- SHS:

-

Second Hand Smoke

References

World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use-third edition [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 Jul 7]. p. 121. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-report-on-trends-in-prevalence-of-tobacco-use-2000-2025-third-edition.

World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. 2019. Offer help to quit tobacco use. [Internet]. Fresh and alive MPOWER. 2019 [cited 2020 Nov 23]. p. 109. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/offer/en/.

Lee K, Eckhardt J, Holden C. Tobacco industry globalization and global health governance: towards an interdisciplinary research agenda. Palgrave Commun. 2016 Dec 5;2(1):16037.

Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, Bialous SA, Jackson RR. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London England). 2015 Mar;14(9972):1029–43.

Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(Suppl 1(01)):117–29.

World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025, second edition [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2022 May 31]. p. 121. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272694/9789241514170-eng.pdf.

Mackay J, Eriksen M. The tobacco atlas. [Internet]. Publications of the World Health Organization. 2002. p. 2–50. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42580.

World Heath Organization. Tobacco Control in the South-East Asia Region [Internet]. Tobacco. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/tobacco/tobacco-control-in-the-south-east-asia-region.

Ruhil R. India has reached on the descending limb of tobacco epidemic. Indian J Community Med. 2018 Jul 1;43(3):153–6.

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India. Global Adult Tobacco Surey 2016–2017 [Internet]. International Institute for Population Sciences. 2017 [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/GlobaltobacoJune2018.pdf.

Tiwari RV, Gupta A, Agrawal A, Gandhi A, Gupta M, Das M. Women and Tobacco Use: Discrepancy in the Knowledge, Belief and Behavior towards Tobacco Consumption among Urban and Rural Women in Chhattisgarh, Central India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015 Oct;6(15):6365–73.

Dieleman LA, Van Peet PG, Vos HMM. Gender differences within the barriers to smoking cessation and the preferences for interventions in primary care a qualitative study using focus groups in The Hague, The Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2021 Jan 29;11(1).

Smith PH, Bessette AJ, Weinberger AH, Sheffer CE, McKee SA. Sex/gender differences in smoking cessation: A review. Prev Med (Baltim). 2016 Nov;1:92:135–40.

Goel S, Tripathy JP, Singh RJ, Lal P. Smoking trends among women in India: Analysis of nationally representative surveys (1993–2009). South Asian J Cancer. 2014 Oct;3(4):200–2.

Ekpu VU, Brown AK. The Economic Impact of Smoking and of Reducing Smoking Prevalence: Review of Evidence. Tob Use Insights. 2015 Jan;8:TUI.S15628.

Felix AS, Yang HP, Gierach GL, Park Y, Brinton LA. Cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk: the role of effect modification and tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Apr;25(4)(1):479–89.

Office of the Surgeon General (US), Office on Smoking and Health (US). The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. Reports of the Surgeon General. 2004 [cited 2021 Apr 14]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20669512/.

Xue F, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Michels KB. Cigarette smoking and the incidence of breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jan;24(2):125–33.

Kapeu AS, Luostarinen T, Jellum E, Dillner J, Hakama M, Koskela P, et al. Is smoking an independent risk factor for invasive cervical cancer? A nested case-control study within Nordic biobanks. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Feb;169(4):480–8.

Samet JM, Yoon S-Y. World Health Organization. Gender, women, and the tobacco epidemic [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2021 Apr 14]. p. 249. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44342/9789241599511_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. Analysis and Reporting Package: Fact Sheet Templates. [Internet]. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). 2020 [cited 2022 Aug 22]. p. 176. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/gats/18_gats_analysispackage_final_23nov2020.pdf?sfvrsn=67e2065f_3.

Verma M, Kathirvel S, Das M, Aggarwal R, Goel S. Trends and patterns of second-hand smoke exposure amongst the non-smokers in India-A secondary data analysis from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) I & II. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0233861.

Kankaria A, Sahoo SS, Verma M. Awareness regarding the adverse effect of tobacco among adults in India: findings from secondary data analysis of Global Adult Tobacco Survey. BMJ Open. 2021 Jun 1;11(6):e044209.

Tripathy JP, Verma M. Impact of Health Warning Labels on Cigarette Packs in India: Findings from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2016–17. Behav Med. 2020;48(3):171–180.

World Health Organization. Economics of tobacco toolkit: economic analysis of demand using data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) [Internet]. WHO Tobacco Free Initiative. 2010 [cited 2021 Apr 23]. p. 87 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/economics-of-tobacco-toolkit-economic-analysis-of-demand-using-data-from-the-global-adult-tobacco-survey.

Tripathy JP. Socio-demographic correlates of quit attempts and successful quitting among smokers in India: Analysis of Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2016-17. Indian J Cancer. 2018;58(3):394–401.

Amos A, Greaves L, Nichter M, Bloch M. Women and tobacco: a call for including gender in tobacco control research, policy and practice. Tob Control. 2012 Mar 1;21(2):236–43.

Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 2005 Jun;100(6):837–51.

Rahmanian SD, Diaz PT, Wewers ME. Tobacco use and cessation among women: research and treatment-related issues. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011 Mar 1;20(3):349–57.

Asma S, Mackay J, Yang Song S, Zhao L, Morton J, Palipudi KM, et al. The GATS Atlas [Internet]. CDC Foundation. 2015. p. 40, 120. Available from: http://gatsatlas.org/.

Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). M and M of H and FW, Government of India. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS),Second Round, India 2016-17.

Jung-Choi KH, Khang YH, Cho HJ. Hidden female smokers in Asia: A comparison of self-reported with cotinine-verified smoking prevalence rates in representative national data from an Asian population. Tob Control. 2012 Nov;21(6):536–42.

Sasco AJ. Africa: a desperate need for data. Tob Control. 1994;3(3):281.

Centre for Disease Control. The Tobacco Industry’s Influences on the Use of Tobacco Among Youth. In: Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2012.

Saladin ME, Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, LaRowe SD, DeSantis SM, Upadhyaya HP. Gender differences in craving and cue reactivity to smoking and negative affect/stress cues. Am J Addict. 2012 May;21(3):210–20.

Sinha DN, Gupta PC, Kumar A, Bhartiya D, Agarwal N, Sharma S, et al. The Poorest of Poor Suffer the Greatest Burden From Smokeless Tobacco Use: A Study From 140 Countries. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Nov 15;20(12):1529–32.

Nargis N, Hussain AKMG, Fong GT. Smokeless tobacco product prices and taxation in Bangladesh: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Survey. Indian J Cancer. 2014 Oct 1;51(0 1):S33–8.

Suliankatchi Abdulkader R, Sinha DN, Jeyashree K, Rath R, Gupta PC, Kannan S, et al. Trends in tobacco consumption in India 1987–2016: impact of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Int J Public Health. 2019 Jul;64(6)(1):841–51.

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS). Smokeless tobacco and public health: A global perspective [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 May 3]. Available from: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/smokeless-tobacco.

Srinath K, Prakash R, Gupta C. Tobacco Control in India.

Boffetta P, Hecht S, Gray N, Gupta P, Straif K. Smokeless tobacco and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):667–75.

PC G. S S. Smokeless tobacco use, birth weight, and gestational age: population based, prospective cohort study of 1217 women in Mumbai, India. BMJ. 2004 Jun;26(7455):1538–40.

PC G. S S. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of stillbirth: a cohort study in Mumbai, India. Epidemiology. 2006 Jan;17(1):47–51.

Verma RC, Chansoriya M, Kaul KK. Effect of tobacco chewing by mothers on fetal outcome. Indian Pediatr. 1983;20(2):105–11.

Nair S, Schensul JJ, Begum S, Pednekar MS, Oncken C, Bilgi SM, et al. Use of Smokeless Tobacco by Indian Women Aged 18–40 Years during Pregnancy and Reproductive Years. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 18;10(3):e0119814.

Milcarz M, Polanska K, Bak-Romaniszyn L, Kaleta D. Tobacco health risk awareness among socially disadvantaged people—A crucial tool for smoking cessation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Oct 13;15(10):113.

Majmudar PV, Mishra GA, Kulkarni SV, Dusane DR, Shastri SS. Tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices among urban low socioeconomic women in Mumbai, India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2015 Mar 1;36(1):32–7.

Demaio AR, Nehme J, Otgontuya D, Meyrowitsch DW, Enkhtuya P. Tobacco smoking in mongolia: Findings of a national knowledge, attitudes and practices study. BMC Public Health. 2014 Feb;28(1):213.

Cummings KM, Hyland A, Giovino GA, Hastrup JL, Bauer JE, Bansal MA. Are smokers adequately informed about the health risks of smoking and medicinal nicotine? Nicotine Tob Res. 2004 Dec;6(SUPPL. 3).

World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Bonnie RJ, Stratton K, Kwan LY, Products C on the PHI of R the MA for PT, Practice B on PH and PH, Medicine I of. The Effects of Tobacco Use on Health. 2015 Jul.

Ampelas DG. Current and former smokers and hip fractures. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018 Sep;03(03):148–54.

Iacobelli M, Saraf S, Welding K, Clegg Smith K, Cohen JE. Manipulated: Graphic health warnings on smokeless tobacco in rural India. Mar 1: Tobacco Control BMJ Publishing Group; 2020. pp. 241–2.

Volchan E, David IA, Tavares G, Nascimento BM, Oliveira JM, Gleiser S, et al Implicit Motivational Impact of Pictorial Health Warning on Cigarette Packs. Miaskowski C, editor. PLoS One. 2013 Aug 15;8(8):e72117.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Are there gender differences in tobacco smoking? [Internet]. Tobacco, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes Research Report. 2020 [cited 2021 May 3]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/tobacco-nicotine-e-cigarettes/references.

Al’Absi M, Nakajima M, Allen S, Lemieux A, Hatsukami D. Sex differences in hormonal responses to stress and smoking relapse: A prospective examination. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 Jun 23;17(4):382–9.

Perkins KA, Karelitz JL. Sex differences in acute relief of abstinence-induced withdrawal and negative affect due to nicotine content in cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 Jun 23;17(4):443–8.

Smith PH, Kasza KA, Hyland A, Fong GT, Borland R, Brady K, et al. Gender differences in medication use and cigarette smoking cessation: Results from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 Jun 23;17(4):463–72.

Harris KK, Zopey M, Friedman TC. Metabolic effects of smoking cessation. Vol. 12, Nature Reviews Endocrinology. Nature Publishing Group; 2016. pp. 299–308.

Verma M, Bhatt G, Nath B, Kar SS, Goel S. Tobacco consumption trends and correlates of successful cessation in Indian females: Findings of Global Adult Tobacco Surveys. Indian J Tuberc. 2021;68S:29–38.

United Nations. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [Internet]. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. [cited 2021 May 4]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/indexphp?page=view&type=30022&nr=665&menu=3170.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Authors received no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LDG conceptualized the study. MV drafted an analysis plan, conducted all the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. PG, GB drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical clearance

Since it was a secondary data analysis of completely anonymized national datasets available in the public domain, ethical approval was waived by the Institutional Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences Bathinda vide letter no. IEC/AIIMS/BTI/069, dated 19-02-2021. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None of the authors has conflicting interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Goyal, L.D., Verma, M., Garg, P. et al. Variations in the patterns of tobacco usage among indian females - findings from the global adult tobacco survey India. BMC Women's Health 22, 442 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02014-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02014-3