Abstract

Background

Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (PGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors, with an estimated incidence of about 0.6 cases per 100.000 person/year. Overall, 3–8% of them are malignant. These tumors are characterized by a classic triad of symptoms (headaches, palpitations, profuse sweating) due to hypersecretion of catecholamines. Despite several advantages of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for PGL debulking, the surgical approach is not standardized yet. In this scenario, we aimed to report a case of a multiple recurrent PGL with metastatic retroperitoneal localization involving the pelvic sidewall, excised with MIS.

Case presentation

We performed complete laparoscopic-assisted neuronavigation (LANN technique) with isolation of the sacral routes and the sciatic nerve to obtain complete exposure of the main anatomic landmarks. Robotic surgery was used to perform neurolysis of sacral plexus, and partial resection of left splanchnic nerves was needed. After the resection of the first mass, extensive neurolysis of all sacral routes, obturator nerve, pudendal nerve till the entrance of the pudendal (Alcock) canal, and sciatic nerve was performed. Finally, the mass was identified after trans gluteal incision and dissection of the maximum gluteal muscle, and a partial resection of the superior gluteal nerve and slicing of the sciatic nerve were needed to obtain a radical excision of the mass. Then neurorrhaphy of the sectioned nerve fibers of the superior gluteal nerve was performed, and nerve protection was obtained using a collagen nerve wrap. After 18 months of follow-up, the patient is free of disease at the MRI imaging and 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy.

Conclusions

Minimally invasive gynecological surgery with neuropelveological approach could be considered as a feasible option in case of multifocal pelvic retroperitoneal malignant paraganglioma of the pelvic side wall.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pheochromocytoma (PH) and Paraganglioma (PGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors, with an estimated incidence of about 0.6 cases per 100.000 person/year. Overall, 3–8% of those cases are malignant [1]. PH and PGL are characterized by a classic triad of symptoms (headaches, palpitations, profuse sweating) due to hypersecretion of catecholamines [2]. Anatomical location is used to differentiate the two tumor types: PH is an adrenal tumor, while PGL is an extra-adrenal tumor. The PGL affecting sympathetic system is most often located in the retroperitoneum, along with the thoracolumbar paravertebral region and the bladder; conversely, the involvement of the pelvic sidewall is very rare [3]. Complete surgical excision of the PGL is the first-line approach, while metastatic or recurrent tumors often require further adjuvant treatments. Despite several advantages of Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) for PGL debulking, the surgical approach is not standardized yet. Only a few studies reporting the resection of pelvic isolated retroperitoneal PGL through MIS have been published and, to the best of our knowledge, multiple recurrent PGL with metastatic localization resected with an endoscopic approach has not been described so far.

In this scenario, we aimed to report a case of a multiple recurrent PGL with metastatic retroperitoneal localization involving the pelvic sidewall, excised with MIS.

Case presentation

A nulliparous 29-year-old woman was referred to our Institution due to a second paraganglioma recurrence with systemic symptoms. She did not have family history of PH/PGL syndrome. The first diagnosis of PGL was in 2003, after an urgent laparotomic resection of a pelvic mass with concomitant heart failure. In 2006, pelvic Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed the first recurrence with multiple pelvic nodules. Laparotomic debulking was performed, though a non-complete resection of the disease was reported. Post-operative MRI confirmed the persistence of disease in the left pelvic wall, left parametrial tissue and paravesical space. The patient received six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with Etoposide, Doxorubicin and Cisplatin. In November 2020, the patient experienced an exacerbation of hypertension and lipothymia. The patient also complained of hypertensive peaks in supine position.

The pelvic bimanual evaluation allowed to identify a left gluteal mass and a solid mass located in the left pararectal space; invasion of the vaginal and rectal mucosa was not apparent. Interestingly, the compression of the left gluteal mass led to hypertensive peak. In addition, investigation of the pelvic nerves was performed based on neuropelveological criteria [4]. The analysis of the trigger points, performed through the transrectal and transvaginal palpation of the sacral plexus, was negative. Laboratory tests revealed elevated epinephrine levels on blood and urine samples. CA125, CA19-9, CA15-3 and CEA biomarkers were within normal range.

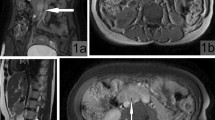

Pre-operative MRI showed multiple pelvic nodules (Fig. 1): a 4.5 × 2.7 × 3 cm mass in the left gluteal region, with suspicious involvement of the sciatic nerve; two contiguous nodules, 2 × 1.7 × 2 cm and 3 × 1.7 × 2 cm, respectively, in the ischiorectal fossa; an 8 mm nodule in the obturator space; a 15 cm mass in the left external iliac region and a 1.4 × 1.7 × 1.5 cm nodule in the vesical-vaginal septum (Fig. 2).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) axial T1 weighted sequencies of the pelvis showing multiple nodules: A irregular nodule in gluteal region between the large gluteal muscle and the piriformis muscle (green arrow). Double nodule at the apex of ischiorectal fossa which is contiguous to the largest gluteal nodule (purple arrow); B two little nodules in the left obturator space, next to distal anal canal (yellow and pink arrow)

After discussion of the case within our multidisciplinary tumor board, including the cardiological and anesthesiologic teams, the patient was scheduled for robotic resection of the pelvic nodules and transgluteal resection of the gluteal mass.

The patient underwent preoperative preparation with alpha (phenoxybenzamine) and beta-blocker (metoprolol) agents the last two weeks before the surgery, in order to stabilize the pressure and avoid abrupt arterial pressure fluctuations during the surgery. A robot-assisted approach was performed using a 4-armed Da Vinci Si platform (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The surgical exploration revealed normal upper abdominal organs, uterus and both ovaries. After access of the retroperitoneum and isolation of the left ureter, the inspection of the pelvis showed a solid bilobed mass in the context of the lateral and left posterior parametrium, adherent to the internal iliac vessels and the parietal endopelvic fascia. Then the dissection of the tumour started, without direct manipulation, to avoid hypertensive crisis. A complete laparoscopic-assisted neuronavigation (LANN technique) was performed, following standardized approach [5, 6], with isolation of the sciatic nerve and sacral routes, aimed to obtain the complete exposure of the main anatomic landmarks (Fig. 3).

Once the inferior hypogastric plexus and the sacral plexus were exposed, a partial involvement of the autonomic pelvic innervation was found. Aiming to obtain a radical excision of the nodule, neurolysis of sacral plexus and partial resection of left splanchnic nerves were needed. After the resection of the first mass, extensive neurolysis of all sacral routes, obturator nerve, pudendal nerve till the entrance of the pudendal (Alcock) canal, and sciatic nerve was performed (Fig. 4a), as previously described [7].

Neurolysis of the left sciatic nerve: A Complete exposure of the sciatic nerve; B Marked sciatic nerve before proceeding with trans gluteal approach (yellow star = obturator nerve; black star = pelvic side wall; red arrow = Alcock canal; white arrow = sciatic nerve; black arrow = marked sciatic nerve)

In the left obturator space, two centimetric nodules strongly adherent to the obturator nerve and vein were removed with concomitant dissection of enlarged obturator lymph nodes. The obturator nerve and vein were safely spared during the debulking procedures.

Subsequently, the vesical-vaginal space was exposed after completely dissecting off the vesical peritoneum, and infiltration of the vaginal and bladder wall was detected. To obtain a complete excision of the nodule, partial centimetric resections of the vaginal and bladder wall were needed, with subsequent single-stiches suture. Filling the bladder with 200 cc of water showed no leakage or diverticula. All specimens were removed within endobag through the 12-mm assistant port.

Once the resection of all pelvic nodules was completed, the patient was placed in prone position. Intraoperative trans-gluteal ultrasound confirmed the 6 cm gluteal nodule in the context of the muscle fibers. The mass was identified after trans gluteal incision and dissection of the maximum gluteal muscle. The tumor was fixed with partial infiltration of the superior gluteal nerve and sciatic nerve, previously marked during the robotic neurolysis (Fig. 4b). A partial dissection of the superior gluteal nerve and slicing of the sciatic nerve were needed to obtain a radical excision of the mass. Then neurorrhaphy of the sectioned nerve fibers of the superior gluteal nerve was performed, and nerve protection was obtained using a collagen nerve wrap. During the operation, the patient presented only slight blood pressure fluctuation following manipulation of the nodules, easily controlled with intravenous α-adrenergic blocker (phentolamine) and β-adrenergic blockers. The procedure was completed by robotic surgery, without complications. Operating time was 480 min, and estimated blood loss was 100 mL. Patient was discharged after 7 days, with an uneventful post-operative period. Final histopathological report confirmed a malignant paraganglioma with poorly differentiated cells [8] with partial vascular invasion.

Immunohistochemistry showed strong positivity for chromogranin, synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase. Conversely, tumor cells were immunohistochemically negative for pan-cytokeratin and S100. Proliferation index was 20%, measured as Ki67 expression. Surgical margins were negative. Two of the nine lymph nodes removed were positive for the presence of metastatic cells.

A clinical follow-up 2 weeks postoperatively showed normal blood pressure and absence of hypertensive crisis. The urinary catheter was removed 30 days after the surgery. After one month, the patient denied any gait disturbance or tenderness to palpation in the area of the left buttock. The patient presented a normal bilateral hip abduction.

A new 24-h urine collection showed normal amounts of catecholamines. Two months after the surgery, a metaiodobenzylguanidine nuclear scan test was performed, showing no abnormal uptake. After discussion in our multidisciplinary tumor board, the patient underwent clinical observation with imaging and laboratory tests. After 18 months of follow-up, the patient was free of disease at the MRI imaging and 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy. No new symptoms or signs were reported.

The patient signed informed consent to allow data collection for research purpose and the publication of the case. This article conforms the Consensus-based Clinical Case Reporting (CARE) Guideline [9], validated by the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) Network. Considering the anonymized reporting of the case, a formal Institutional Review Board approval was waived.

Discussion and conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, the first reported case of a multiple recurrence malignant PGL with retroperitoneal pelvic multifocal localization involving the pelvic side wall. Moreover, the resection was carried out totally through MIS, combining robotic-laparoscopic assisted procedures with a transgluteal approach. Although the complexity of the surgery, a complete resection of all the nodules was achieved without intraoperative complications.

Despite most of the extra-adrenal PGL have low malignant potential, in rare cases a malignant pattern has been observed [10]. Considering its rarity, there are no definitive criteria on histology to clearly differentiate benign from malignant PGL, and malignancy is determined by recurrence or distant metastasis [11]. To date, the only case of malignant recurrence available in the literature is a PGL of the bladder with metastatic pelvic lymph nodes [12]: nevertheless, the surgical approach for the tumor resection has not been reported. Moreover, the pelvic side wall involvement is a very rare scenario for neuroendocrine tumors. In literature, only one report described a case of paraganglioma of the left pelvic wall, abutting the left lateral wall of the urinary bladder, and removed by laparotomic approach [13]. In this scenario, our report describes the first MIS management for PGL of the pelvic side wall, allowing us to highlight the feasibility of this approach as we already reported for other disease of the same anatomical area [14].

The uniqueness of our report is also represented by the multifocal localization, with the presence of a metastasis in the context of the maximum gluteal muscle infiltrating the superior gluteal nerve. Despite the pre-operative imaging represented an important step for evaluation of the involved retroperitoneal structures and extension of the disease [15], the neuropelvic anatomic assessment helped us to obtain a better identification of the involvement of the pelvic nerves by the nodules. In the current case, the absence of somatic pain and motor dysfunction helped us to exclude a massive infiltration of the sacral routes. Moreover, the investigation of the pelvic nerves by vaginal and rectal examination guided us to identify a mass with involvement of the pelvic side wall and concomitant release of catecholamine and hypertension peak during the compression. Therefore, the wide knowledge of the pelvic neuroanatomy was essential to define the location of the nodule and rule out a possible extensive involvement of the sacral plexus. Indeed, the neuropelveology could be considered a new potential tool for the preoperative mapping of the lesions. From this perspective, the results of neuropelveological examination allows for a better and tailored treatment, improving diagnostic accuracy and lesion localization.

Based on clinical and radiological data, the neurogenic lesions were safely accessible thought a combined approach (robotic and transgluteal), although extensive neurolysis of sacral plexus and partial resection of left pelvic parasympathetic innervation and superior gluteal nerve were needed. Overall, several factors contributed to make the surgical management very challenging: among the most important, the multifocal and unusual location of the nodules, the partial infiltration of major vascular structures and pelvic nerves, and the adhesions caused by previous laparotomic surgery with incomplete excision of the disease. For these reasons, in our opinion the support of the robotic system in this complex procedure played a pivotal role for the precise dissection of the highly vascularized tumor with a magnified field of vision and 3D imaging, and allowed minimization of postoperative morbidity and hospital stay. Although our case showed the feasibility of the first robotic resection of a PGL recurrence, other groups reported MIS for PGL and PH as a safe approach: Walz et al. [10] described their successful experience in the largest case series of neuroendocrine tumors excised by using all varieties of endoscopic approaches (transabdominal laparoscopy, retroperitoneoscopic and extraperitoneal approaches). No standardized post-operative treatment guidelines were available, since this condition could be considered extremely rare. Chemotherapy, target therapy, or radiation therapy could be considered as adjuvant treatments after surgical debulking. However, these treatments do not seem to improve survival in patients with neuroendocrine tumors [16].

The decision of clinical follow-up after surgery was discussed in our multidisciplinary tumor board, based on the complete resection achieved and the negative post-operative imaging. Despite the low incidence of this rare entity, each retroperitoneal pelvic mass with concomitant symptoms of catecholamine excess should be potentially considered in the differential diagnosis as a malignant PGL [17]. Nevertheless, even in case of pelvic side wall involvement with nerve infiltration, a surgical excision with a robot-assisted laparoscopic approach seems feasible and safe. Despite the rare incidence of malignant retroperitoneal PGL, further studies are needed to evaluate the optimal method to diagnose and manage this challenging disease.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- PH:

-

Pheochromocytoma

- PGL:

-

Paraganglioma

- MIS:

-

Minimally invasive surgery

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Lefebvre M, Foulkes WD. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma syndromes: genetics and management update. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e8-17.

Lenders JWM, Pacak K, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Mannelli M, Friberg P, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: Which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427–34.

Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014;38:7–41.

Possover M, Forman A, Rabischong B, Lemos N, Chiantera V. Neuropelveology: new groundbreaking discipline in medicine. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1140–1.

Chiantera V, Petrillo M, Abesadze E, Sozzi G, Dessole M, Catello Di Donna M, et al. Laparoscopic neuronavigation for deep lateral pelvic endometriosis: clinical and surgical implications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:1217–23.

Di Donna MC, Cucinella G, Sozzi G, Ianieri MM, Scambia G, Chiantera V. Surgical neuropelviology: combined sacral plexus neurolysis and laparoscopic laterally extended endopelvic resection in deep lateral pelvic endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1565.

Di Donna MC, Cucinella G, Sozzi G, Gueli Alletti S, Lo Re G, Scambia G, et al. Surgical neuropelveology: lateral femoral cutaneous nerve endometriosis. Laparoscopic resection and nerve transplantation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1978–9.

Wachtel H, Hutchens T, Baraban E, Schwartz LE, Montone K, Baloch Z, et al. Predicting metastatic potential in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: a comparison of PASS and GAPP scoring systems. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e4661–70.

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:46–51.

Walz MK, Alesina PF, Wenger FA, Koch JA, Neumann HPH, Petersenn S, et al. Laparoscopic and retroperitoneoscopic treatment of pheochromocytomas and retroperitoneal paragangliomas: results of 161 tumors in 126 patients. World J Surg. 2006;30:899–908.

Chen H, Sippel RS, O’Dorisio MS, Vinik AI, Lloyd RV, Pacak K, et al. The North American neuroendocrine tumor society consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and medullary thyroid cancer. Pancreas. 2010;39:775–83.

Yoo KH, Choi T, Lee H-L, Song MJ, Chung BI. Aggressive paraganglioma of the urinary bladder with local recurrence and pelvic metastasis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26:2827–9.

Yadav S, Banerjee I, Tomar V, Yadav SS. Pelvic paraganglioma: a rare and unusual clinical presentation of paraganglioma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015212851.

Cucinella G, Sozzi G, Di Donna MC, Unti E, Mariani A, Chiantera V. Retroperitoneal squamous cell carcinoma involving the pelvic side wall arising from endometriosis: a case report. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1159/000520983.

Sahdev A, Sohaib A, Monson JP, Grossman AB, Chew SL, Reznek RH. CT and MR imaging of unusual locations of extra-adrenal paragangliomas (pheochromocytomas). Eur Radiol. 2005;15:85–92.

Adjallé R, Plouin PF, Pacak K, Lehnert H. Treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:687–96.

Weingarten TN, Welch TL, Moore TL, Walters GF, Whipple JL, Cavalcante A, et al. Preoperative levels of catecholamines and metanephrines and intraoperative hemodynamics of patients undergoing pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma resection. Urology. 2017;100:131–8.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. was involved in project development, data collection, data evaluation, and manuscript writing. G.C. was involved in project development and manuscript writing. M.C.D.D. was involved in data evaluation and manuscript editing. G.L. was involved data collection and data evaluation. A.S.L. was involved paper assessment and manuscript editing. V.C. was involved project development, manuscript revising, and performed the surgical procedure. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All the authors conform the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship, contributed to the intellectual content of the study and gave approval for the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Considering the fully anonymized report of the case, a formal approval was waived by the “Institutional Review Board of Palermo”. The patient signed informed consent to allow data collection for research purposes.

Consent for publication

The patient signed informed consent to allow publication of the case.

Competing interests

Antonio Simone Laganà is Senior Editorial Board Member of BMC Women's Health, but he was not involved in the editorial processing and/or peer review of the article. The authors have no proprietary, financial, professional or other personal interest of any nature in any product, service or company. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaccaria, G., Cucinella, G., Di Donna, M.C. et al. Minimally invasive management for multifocal pelvic retroperitoneal malignant paraganglioma: a neuropelveological approach. BMC Women's Health 22, 380 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01969-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01969-7