Abstract

Background

Modern contraceptive use has been shown to influence population growth, protect women’s health and rights, as well as prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for barrier contraceptive methods such as condoms. The present study aimed at assessing the level of utilization and factors associated with modern contraceptive use among sexually active adolescent girls in Rwanda.

Methods

We used secondary data from the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (RDHS) 2020 data of 539 sexually active adolescent girls (aged 15 to 19 years). Multistage stratified sampling was used to select study participants. We conducted multivariable logistic regression to assess the association between various socio-demographics and modern contraceptive use using SPSS version 25. Modern contraception included the use of products or medical procedures that interfere with reproduction from acts of sexual intercourse.

Results

Of the 539 sexually active girls, only 94 (17.4%, 95% CI: 13.8–20.1) were using modern contraceptives. Implants (69.1%) and male condoms (12.8%) were the most used options. Modern contraceptive use was positively associated with older age (AOR = 10.28, 95% CI: 1.34–78.70), higher educational level (AOR = 6.98, 95% CI: 1.08–45.07), history of having a sexually transmitted infection (AOR = 8.27, 95% CI: 2.54–26.99), working status (AOR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.03–2.88) and being from a female-headed household (AOR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.12–3.43). However, not being in a union (AOR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.10–0.35) and region (AOR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.10–0.80) had negative associations.

Conclusions

To promote utilisation of modern contraceptives, family planning campaigns need to place more emphasis on the younger, unmarried adolescents, as well as those with lower educational levels. Consideration of household and regional dynamics is also highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of modern contraceptives is essential for protecting women’s health and rights, reducing population growth, and promoting women’s empowerment and economic development [1]. Furthermore, barrier contraceptive methods like condoms are crucial for preventing sexually transmitted infections [1, 2]. Low and middle-income countries (LMICs) have the highest unmet need for modern contraception as over 200 million women who do not want to conceive are not using a modern contraceptive method [3, 4]. This might partly explain the annual 111 million unintended pregnancies and 35 million unsafe abortions occurring in LMICs [5]. Access to modern contraception and adequate care for all women could reduce unintended pregnancies by 68%, unplanned births by 71%, unsafe abortions by 72% and maternal mortality by 62% [4, 5].

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the highest rate of teenage pregnancy and over a third of teenage pregnancies end up as unsafe abortions yet the region also reports the lowest utilization of modern contraceptives [6]. Complications related to pregnancy are the major causes of maternal deaths among adolescents aged 15–19 years in LMICs [6, 7]. Amouzou et al. analyzed national data on coverage of maternal and reproductive health indicators in 58 LMICs and showed that adolescents had lower access and utilization of family planning (FP) interventions than women aged 20–49 years; had the slowest rate of improvement in coverage for SRH (between 2000 and 2017) and children born to teenage mothers were significantly disadvantaged in terms of receiving timely illness treatment and immunisation [8].

Although the East African Community (EAC) region in which Rwanda belongs has registered progress in access to SRH, the region still has major gaps in access and quality of SRH services with a very high unmet need for contraception, especially among adolescents [6, 9, 10]. Despite the government of Rwanda's youth-friendly policies and projects such as the Isange One-Stop Centers and Youth-friendly corners in schools and health facilities that promote SRH to young Rwandans, urban areas such as Kigali are increasingly experiencing unwanted adolescent pregnancies, risky sexual behaviours, and rising HIV infection [9, 11]. The Rwanda demographic health survey (RDHS) 2020 further reports that 15% of adolescents have begun childbearing at the age of 19 years [12]. Moreover, there is limited information on contraceptive use among adolescents in Rwanda, where most of the available studies have looked at women in general [4, 10, 13,14,15,16,17]. In order to formulate evidence-based policies aimed at increasing the utilization of modern contraceptives, there is a need for more recent adolescent-focused studies. Hence our study aimed at assessing the level and associated factors of modern contraceptive use among sexually active adolescent girls in Rwanda using the most recent 2020 RDHS. Our findings might be vital in informing targeted interventions and policies aimed at improving access and utilisation of modern contraceptives.

Methods

Study sampling and participants

We used the 2019–20 Rwanda Demographic Survey (RDHS) for this analysis. It employed a two-stage sample design, with the first stage involving cluster selection consisting of enumeration areas (EAs) [12]. The second stage involved systematic sampling of households in all the selected EAs leading to a total of 13,005 households [12]. In particular, the data used in this analysis were from the household and the woman’s questionnaires.

During this survey, the data collection period was from November 2019 to July 2020, taking longer than expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions [12]. Women aged 15–49 years who were either permanent residents of the selected households or visitors who stayed in the household the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed. Out of the total 13,005 households that were selected for the survey, 12,951 were occupied and 12,949 were successfully interviewed leading to a 100% response rate [12]. The eligible sample was 14,675 women aged 15–49, but 14,634 women were successfully interviewed leading to a 99.7% response rate [12]. This analysis included only adolescent girls aged 15–19 years interviewed during the survey, and from the selected households (n = 3258). For precision of contraceptive use, we focused on the sexually active adolescent girls, whose sample was 539.

Variables

Dependent variables

The study outcome variable was the usage of modern contraceptive methods, and this was a binary variable directly coded yes or no. Modern contraception was considered as the use of a product or medical procedure that interferes with reproduction from acts of sexual intercourse [18] and included implants/Norplant, male condoms, injections, and pills.

Explanatory variables

We included possible determinants of modern contraceptive use based on the available literature and data [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Thirteen (13) variables were considered and of these, two were community-level factors that included; place of residence (categorized into rural and urban), and region of residence (categorized into Kigali, South, West, East and North). Four household-level factors included; household size which was classified into “less than six” and “six and above”, sex of household head (classified as female and male), wealth index (categorized into five quintiles that ranged from the poorest to the richest quintile), and health insurance (categorised as yes and no). Wealth index was calculated by RDHS from information on household asset ownership using Principal Component Analysis [12]. Seven individual-level factors were also considered in the analysis, including; age (categorized as 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 years), educational level (grouped as no education, primary, secondary and tertiary), working status (working and not working), being in a union (living with partner and not in a union), religion (Catholic, Protestant, and others), history of having an STI in last 12 months (yes and no), and exposure to news, radio and television (yes and no).

Statistical analysis

We applied the DHS sample weights to account for the unequal probability sampling in different strata and ensure the representativeness of the study results [25, 26]. We used SPSS (version 25.0) statistical software complex samples package incorporating the following variables in the analysis plan to account for the multistage sample design inherent in the RDHS dataset: individual sample weight, sample strata for sampling errors/design, and cluster number [12, 25]. Frequency distributions were used to describe the background characteristics of the sexually active adolescent girls; where frequencies and proportions/percentages for categorical dependent and independent variables have been presented. Bivariable logistic regression was then conducted to assess the association of each predictor variable with modern contraceptive use, and we presented crude odds ratio (COR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-values. Independent variables found significant at a p-value less than 0.25 were then included in the multivariable model. Moreover, independent variables that were non-significant at the bivariable analysis level but were associated with contraceptive use in previous studies were also included in the multivariable logistic regression model. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were calculated and presented, with a statistical significance level set at p-value < 0.05.

Since a small fraction of the adolescent girls was sexually active (16.5%, 539/3258), we conducted a sensitivity analysis where we considered all adolescent girls regardless of their sexual activity to examine any differences in predictor variables of modern contraceptive use. All socio-demographic variables in the model were assessed for multi-collinearity, which was considered present if the variables had a variance inflation factor (VIF) greater than 10 [27]. However, none of the variables had a VIF above 3.

Results

A total of 539 sexually active adolescent girls were included in this analysis (Table 1). The majority were aged 18 and 19 years (62.4%), had primary education (63.6%), were working (54.5%), were rural residents (78.4%), and were from male-headed households (67.0%) of less than 6 household members (55.9%). Moreover, the majority of the respondents had health insurance (79.9%), exposure to radio (80.5%) and television (52.3%), but no exposure to newspapers (70.4%), as detailed in Table 1.

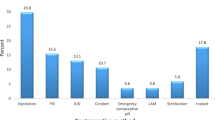

Of the 539 sexually active girls, only 94 (17.4%, 95% CI: 13.8–20.1) were using modern contraceptives, and implants (69.1%) and male condoms (12.8%) were the most used options, as shown in Table 2.

Factors associated with modern contraceptive use

Results of the bivariable analysis with their respective crude odds ratios and p-values are detailed in Table 3. In the final multiple logistic regression model, the factors found significantly associated with contraceptive use were; age, educational level, history of having a sexually transmitted infection (STI), being in a union, and region.

Compared to girls of 15 years of age, those of 19 years were 10.28 (95% CI: 1.34–78.71) times more likely to use modern contraceptives, while those with tertiary education were 6.98 (95% CI: 1.08–45.07) times more likely to use contraceptives compared to their counterparts with no education. Adolescent girls with a history of an STI within the last 12 months were also 8.27 (95% CI: 2.54–26.99) times more likely to use modern contraceptives compared to those with no STI history. However, unmarried adolescents (ie not in union) were 82% less likely to use modern contraceptives compared to adolescents living with partners (AOR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.10–0.35), and those residing in Kigali were 72% less likely to use contraceptives compared to their fellows in the Southern region (AOR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.099–0.802).

Sensitivity analysis considering all adolescent girls regardless of sexual activity

Results of sensitivity analysis are detailed in Table 4, with some changes noted in the significant predictor variables. Compared to the first analysis, educational level became non-significant on sensitivity analysis and two more factors, that is work status and sex of household head become significant predictors of modern contraceptive use. The other variables remained significant with minor changes noted only in the magnitude of associations.

Working adolescents had 1.72 (95% CI: 1.03–2.88) more odds of using modern contraceptives compared to those not working, and those from female-headed households had 1.96 (95% CI: 1.12–3.43) more odds of using contraceptives compared to their counterparts in male-headed households.

Compared to the first analysis of only sexually active adolescents, sensitivity analysis results clearly indicate that modern contraceptive use increases with age, a significant trend noted in age groups of 17, 18 and 19 years (Table 4).

Discussion

Contraceptive use among adolescents was very low (17.4%), similar to Mali (17.1%) [28], but higher than Uganda (9.4%) [6], Benin (8.5%) [29], Nigeria (14.8%) [30], Nepal (11.9%) [31] and Zambia (12%) [32], according to previous studies. Nonetheless, the Government of Rwanda has put considerable efforts in family planing and reducing unwanted pregnancies as part of its 2030 Family Planing country commitment agenda. Evidence from RDHS shows that modern contraceptives are freely available to adolescent girls from government health facilities [33,34,35]. However, reasons for the low usage cited among adolescents include; not being married, infrequent sex and not having sex among the unmarried, and menses not returned after giving birth, breastfeeding and fear of side-effects or health concerns among those in unions [35]. However other factors such as lack of awareness and limited sex education in schools and households, misconceptions regarding contraceptive effects on reproduction, negative cultural implications and poor access to services especially in rural areas should be investigated and addressed [36, 37]. In addition, youth access to quality sexual and reproductive services should be expanded since it is a vital component of the sustainable development goals [38], which have less than 10 years to be achieved.

Even when compared to male condoms (12.8%), implants (69.1%) were by far the most popular modern contraceptive method among sexually active Rwandan female youth. This is surprising given that male condoms are non-invasive and more readily available in small shops and local pharmacies as opposed to implants and other modern methods, which require a visit to a health facility and are frequently preceded by a fear of unwanted effects including fertility interference due to their hormonal nature [39,40,41]. These findings contradict Dennis et al. (2017), who argue that there is a shift from condoms and pills, which are short-term methods, to injectable contraception and much lower use of long-term methods such as implants and IUD, the reason being that at such a young age, the majority of women are unmarried and having infrequent sex, and thus opting for methods that are easier to use and stop as needed [42]. Nonetheless, our finding could perhaps be explained by the increased availability of implants over other methods, and the inherent convenience advantage of implants due to their longer protective period, thus no need to use/replace them more frequently.

Age, level of education, being in a union, region of residence and history of having a sexually transmitted infection (STI) were all associated with the use of modern contraceptive methods. The odds of using modern contraception increased with age, a factor that has previously been linked with modern contraceptive use [43, 44]. This is not surprising given that older adolescents have more maturity and risk awareness than younger adolescents and are thus more inclined to avoid the negative ramifications of not using it [43, 44]. Another reason could be that older adolescents have a higher level of education, which has previously been demonstrated to positively impact modern contraceptive use [1, 30, 44, 45]. In this study, young women with primary, secondary, and university education were all more likely to use contraception than those with no education, demonstrating that a lack of education correlates with reduced opportunity to learn about modern contraception. Education has been related to women's empowerment and increased awareness of their bodies, reproductive health, and other health information, as well as a better understanding of the value of controlling their birth history regarding their productivity and prospective career development [46, 47]. Therefore, additional efforts are needed to increase girls' education and enhance their awareness about modern contraceptives, as well as general access and comprehension of health-related services, which helps to debunk widespread misconceptions about contraceptive use and effects.

Being in a union was also identified as significantly associated with the use of modern contraceptives. Unmarried adolescents were less likely to be using modern contraceptives compared to those living with partners, a finding previously found in other studies [28, 44, 48, 49]. This is surprising given Rwanda's cultural context, where pregnancy before marriage is highly stigmatized for the girl who "loses agaciro or value" and is perceived as a source of shame for her family [50]. Therefore, even though the Rwandan government provides all women with low-cost or free family planning services through community health insurance or Mutuelles de santé, unmarried females are at a higher risk of STIs, unexpected pregnancies, and possibly unsafe abortions due to the emphasis placed on virginity and the resulting fear of being judged or labelled for having premarital sex, which prevents girls from seeking modern contraceptives unless they are married [50].

Adolescent girls with a recent history of STI had a higher likelihood of using modern contraception than those with no STI history. A plausible explanation could be the urge to protect themselves from recurrence of infection. Furthermore, they may have boosted their chances of being taught about the benefits of contraceptive methods when receiving care at a health centre.

While female adolescents in the Northern and Eastern regions were more likely to use modern contraception, those in Kigali, Rwanda's capital and predominantly urban city were less likely to use contraception than their counterparts in the Southern region. This contradicts prior research [51, 52]. which revealed that women in urban areas use contraception more than those in rural areas, possibly due to more exposure to numerous streams of information, proximity to health services, and easier access to a wider range of methods to choose from. This study's findings, however, confirm those of a prior study [1], which revealed that contraceptive use is highest in the Northern region of Rwanda, despite a primarily hilly terrain and difficulties in reaching health facilities [53], most likely due to the region's high presence of non-governmental health organizations that emphasize access to sexual and reproductive health services.

A sensitivity analysis that included all female adolescents regardless of sexual activity found identical results to the previous analysis, except that educational level was no longer a significant predictor of modern contraception use. Two new factors emerged: working status and the gender of the household head. Working adolescents were more likely to use modern contraceptives than those not working, a finding also seen elsewhere in similar studies [1, 54] which could be because women who are employed and able to support themselves financially are more likely to be educated and have greater access to contraception and other information. Furthermore, their career duties and goals may be prompting them to regulate and space births. Finally, female adolescents from female-headed households had higher odds of using contraceptives compared to their counterparts in male-headed households. Despite the fact that female-headed households face a variety of personal, familial, and social challenges, a prior study [55] found that becoming the head of the household is also associated with increased social maturity, which may enable mothers to understand the importance of conversing to their children about social issues and conveying health-related information. The influence of household headship on children's and adolescents' health-seeking behaviour should be further explored.

Strength and limitations

Since the RDHS data used in this study is nationally representative, the results can be generalized to other Rwandan female populations between the ages of 15 and 19 years. DHS data is also known for generating substantial data, with high response rates, high-quality interviewer training, standardized data collection processes across countries, and consistent content across time, allowing these findings to be compared across populations and over time to assess trends [56]. Nevertheless, because the replies are self-reported and cannot be verified, there is a risk of information bias due to the sensitive nature of sexually related topics. Moreover, the cross-sectional methodology used in this study simply allows for assessing the prevalence and investigating the association between exposures and outcomes without drawing any causal inferences.

Conclusions

In this study, age, level of education, being in a union, residence region, history of a sexually transmitted infection, working status, as well as the gender of the household's head were all found to be associated with modern contraception use among Rwandan female adolescents. As a result, family planning campaigns should place a greater emphasis on younger, unmarried adolescents, as well as those with a lower educational level. This also highlights the need to promote not only the availability or accessibility of contraceptives but also training to address fallacious cultural beliefs that may impede modern contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents, which has been linked to several negative outcome measures that may limit their prospects. This can be achieved if the government and other stakeholders engage more in outreach and community-based projects aimed at improving youth sexual and reproductive health, as well as training to improve healthcare providers' ability to provide youth-friendly services. Family planning strategies and techniques should be adjusted to meet the particular needs of different communities, age groups, marital and working status of women, diverse geographical areas, and so on, in order to reach the largest number of women possible.

Availability of data and materials

The data set used is openly available upon permission from the MEASURE DHS website (URL: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm). However, authors are not authorized to share this data set with the public but anyone interested in the data set can seek it with written permission from the MEASURE DHS website (URL: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm).

Abbreviations

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- LMICs:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable development goals

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- DHS:

-

Demographic Health Survey

- RDHS:

-

Rwanda Demographic Health Survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social science

References

Habyarimana F, Ramroop S. Spatial analysis of socio-economic and demographic factors associated with contraceptive use among women of childbearing age in Rwanda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2383.

Kawuki J, Kamara K, Sserwanja Q. Prevalence of risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus among women of reproductive age in Sierra Leone: a 2019 nationwide survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):60.

Guttmacher Institute. Adding It Up: Investing in Contraception and Maternal and Newborn Health. New York, New York; 2020.

Corey J, Schwandt H, Boulware A, Herrera A, Hudler E, Imbabazi C, King I, Linus J, Manzi I, Merrit M, et al. Family planning demand generation in Rwanda: Government efforts at the national and community level impact interpersonal communication and family norms. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0266520.

Guttmacher Institute. Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/investing-sexual-and-reproductive-health-low-and-middle-income-countries. Accessed 11th Aug 2022.

Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mukunya D. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptives utilization among female adolescents in Uganda. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):61.

de Vargas Nunes Coll C, Ewerling F, Hellwig F, de Barros AJD. Contraception in adolescence: the influence of parity and marital status on contraceptive use in 73 low-and middle-income countries. Reprod Health 2019, 16(1):21

Amouzou A, Jiwani SS, Da Silva ICM, Carvajal-Aguirre L, Maïga A, Vaz LM. Closing the inequality gaps in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health coverage: slow and fast progressors. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(1):e002230.

Ndayishimiye P, Uwase R, Kubwimana I. Niyonzima JdlC, Dzekem Dine R, Nyandwi JB, Ntokamunda Kadima J: Availability, accessibility, and quality of adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services in urban health facilities of Rwanda: a survey among social and healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):697.

Bakibinga P, Matanda DJ, Ayiko R, Rujumba J, Muiruri C, Amendah D, Atela M. Pregnancy history and current use of contraception among women of reproductive age in Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda: analysis of demographic and health survey data. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009991.

Ministry of Health. National Family Planning and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health (FP/ASRH) Strategic Plan (2018–2024). 2018.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda - NISR, Ministry of Health - MOH, ICF: Rwanda demographic and health survey 2019–20. In. Kigali, Rwanda and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NISR/MOH/ICF; 2021.

Muhoza DN, Rutayisire PC, Umubyeyi A. Measuring the success of family planning initiatives in Rwanda: a multivariate decomposition analysis. J Popul Res. 2016;33(4):361–77.

Scanteianu A, Schwandt HM, Boulware A, Corey J, Herrera A, Hudler E, Imbabazi C, King I, Linus J, Manzi I et al: “…the availability of contraceptives is everywhere.”: coordinated and integrated public family planning service delivery in Rwanda. Reproductive Health 2022, 19(1):22.

Schwandt H, Boulware A, Corey J, Herrera A, Hudler E, Imbabazi C, King I, Linus J, Manzi I, Merritt M, et al. An examination of the barriers to and benefits from collaborative couple contraceptive use in Rwanda. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):82.

Schwandt H, Boulware A, Corey J, Herrera A, Hudler E, Imbabazi C, King I, Linus J, Manzi I, Merritt M, et al. Family planning providers and contraceptive users in Rwanda employ strategies to prevent discontinuation. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):361.

Bakibinga P, Matanda D, Kisia L, Mutombo N. Factors associated with use of injectables, long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods (iLAPMs) among married women in Zambia: analysis of demographic and health surveys, 1992–2014. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):78.

Hubacher D, Trussell J. A definition of modern contraceptive methods. Contraception. 2015;92(5):420–1.

Ngerageze I, Mukeshimana M, Nkurunziza A, Bikorimana E, Uwishimye E, Mukamuhirwa D, Mbarushimana J, Bahaya F, Nyirasafari E, Mukabizimana J, Niyitegeka P. Knowledge and Utilization of Contraceptive Methods among Secondary School Female Adolescents in Rwamagana District, Rwanda. Rwanda J Med Health Sci. 2022;5(1):71–84.

Ngerageze I. Utilization of contraceptive methods among secondary school female adolescents at a selected secondary school in Rwamagana district, Rwanda (Doctoral dissertation, University of Rwanda).

Marrone G, Abdul-Rahman L, De Coninck Z, Johansson A. Predictors of contraceptive use among female adolescents in Ghana. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(1):102–9.

Davies SL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Person SD, Dix ES, Harrington K, Crosby RA, Oh K. Predictors of inconsistent contraceptive use among adolescent girls: findings from a prospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(1):43–9.

Ahinkorah BO. Predictors of modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: a mixed effects multilevel analysis of data from 29 demographic and health surveys. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5(1):1–2.

Makola L, Mlangeni L, Mabaso M, Chibi B, Sokhela Z, Silimfe Z, Seutlwadi L, Naidoo D, Khumalo S, Mncadi A, Zuma K. Predictors of contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) aged 15 to 24 years in South Africa: results from the 2012 national population-based household survey. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):1–7.

Croft TN, Marshall AM, Allen CK, Arnold F, Assaf S, Balian S. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville: ICF. 2018;645.

Zou D, Lloyd JE, Baumbusch JL. Using SPSS to analyze complex survey data: a primer. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2020;18(1):16.

Johnston R, Jones K, Manley D. Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: a cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1957–76.

Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Appiah F, Budu E, Adu C, Aderoju YB, Adoboi F, Ajayi AI. Individual and community-level factors associated with modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women in Mali: a mixed effects multilevel analysis of the 2018 Mali demographic and health survey. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5(1):1–2.

Ahissou NC, Benova L, Delvaux T, Gryseels C, Dossou JP, Goufodji S, Kanhonou L, Boyi C, Vigan A, Peeters K, Sato M. Modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women in Benin: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e054188.

Oye-Adeniran BA, Adewole IF, Umoh AV, Oladokun A, Gbadegesin A, Ekanem EE. Community-based study of contraceptive behaviour in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006;10(2):90–104.

Angdembe MR, Sigdel A, Paudel M, Adhikari N, Bajracharya KT, How TC. Modern contraceptive use among young women aged 15–24 years in selected municipalities of Western Nepal: results from a cross-sectional survey in 2019. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e054369.

Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mutisya LM, Mukunya D. Rural-urban correlates of modern contraceptives utilization among adolescents in Zambia: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:324. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01914-8.

Rublic of Rwanda Ministry of Health. National Family Planning and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health (FP/ASRH) Strategic Plan (2018–2024). July 2018. https://moh.prod.risa.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Moh/Publications/Strategic_Plan/Rwanda_Adolescent_Strategic_Plan_Final.pdf. Accessed 11th Aug 2022.

Corey J, Schwandt H, Boulware A, Herrera A, Hudler E, Imbabazi C, King I, Linus J, Manzi I, Merrit M, Mezier L. Family planning demand generation in Rwanda: Government efforts at the national and community level impact interpersonal communication and family norms. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0266520.

World Health Organisation. Adolescent contraceptive use: Data from the Rwanda demographic and health survey (RDHS), 2014–15. https://www.rhsupplies.org/uploads/tx_rhscpublications/Republic_of_Rwanda_-_Adolescent_contraceptive_use__data_from_2014-15__02.pdf. Accessed 11th Aug 2022.

Campbell M, Sahin-Hodoglugil NN, Potts M. Barriers to fertility regulation: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. 2006;37(2):87–98.

Williamson LM, Parkes A, Wight D, Petticrew M, Hart GJ. Limits to modern contraceptive use among young women in developing countries: a systematic review of qualitative research. Reprod Health. 2009;6(1):1–2.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goal 3. (2015). https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3. Accessed 12 May 2022

Carter MW, Bergdall AR, Henry-Moss D, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Hock-Long L. A qualitative study of contraceptive understanding among young adults. Contraception. 2012;86(5):543–50.

Cheung E, Free C. Factors influencing young women’s decision making regarding hormonal contraceptives: a qualitative study. Contraception. 2005;71(6):426–31.

Emermitia RL, Livhuwani M, Rambelani N, Maria MT. Views of adolescent girls on the use of implanon in a public primary health care clinic in Limpopo province South Africa. Open Public Health J. 2019;12(1):276–83.

Dennis ML, Radovich E, Wong KL, Owolabi O, Cavallaro FL, Mbizvo MT, Binagwaho A, Waiswa P, Lynch CA, Benova L. Pathways to increased coverage: an analysis of time trends in contraceptive need and use among adolescents and young women in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–3.

Nsanya MK, Atchison CJ, Bottomley C, Doyle AM, Kapiga SH. Modern contraceptive use among sexually active women aged 15–19 years in North-Western Tanzania: results from the Adolescent 360 (A360) baseline survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e030485.

Nyarko SH. Prevalence and correlates of contraceptive use among female adolescents in Ghana. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):1–6.

Saleem S, Bobak M. Women’s autonomy, education and contraception use in Pakistan: a national study. Reprod Health. 2005;2(1):1–8.

Alonge SK. Determinants of women empowerment among the Ijesa of South-western Nigeria. Devel Country Studies. 2014;4(24):2225–565.

Boateng GO, Mumba D, Asare-Bediako Y, Boateng MO. Examining the correlates of gender equality and the empowerment of married women in Zambia. African Geogr Rev. 2014;33(1):1–8.

Aryeetey R, Kotoh AM, Hindin MJ. Knowledge, perceptions and ever use of modern contraception among women in the Ga East District, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010;14(4).

Ahinkorah BO, Hagan JE Jr, Seidu AA, Sambah F, Adoboi F, Schack T, Budu E. Female adolescents’ reproductive health decision-making capacity and contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: What does the future hold? PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0235601.

Berry ME. When “bright futures” fade: Paradoxes of women’s empowerment in Rwanda. Signs: J Women Culture Soc. 2015;41(1):1–27.

Mandiwa C, Namondwe B, Makwinja A, Zamawe C. Factors associated with contraceptive use among young women in Malawi: analysis of the 2015–16 Malawi demographic and health survey data. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3(1):1–8.

Apanga PA, Kumbeni MT, Ayamga EA, Ulanja MB, Akparibo R. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 20 African countries: a large population-based study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e041103.

Bazirete O, Nzayirambaho M, Umubyeyi A, Karangwa I, Evans M. Risk factors for postpartum haemorrhage in the Northern Province of Rwanda: a case control study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0263731.

Hlongwa M, Mashamba-Thompson T, Makhunga S, Hlongwana K. Evidence on factors influencing contraceptive use and sexual behavior among women in South Africa: a scoping review. Medicine. 2020;99(12):e19490.

Yoosefi Lebni J, Mohammadi Gharehghani MA, Soofizad G, et al. Challenges and opportunities confronting female-headed households in Iran: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20:1–11.

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1602–13.

Acknowledgements

We thank the DHS program for making the data available for this study.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QS, JK and GG Conceived the idea, drafted the manuscript, performed analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the subsequent versions of the manuscript. DM and MWM reviewed the first draft, helped in results interpretation and drafted the subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

High international ethical standards are ensured during MEASURE DHS surveys and the study protocol is performed following the relevant guidelines. The RDHS 2019 survey protocol was reviewed and approved by the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (RNEC) and the ICF Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from human participants and written informed consent was also obtained from legally authorized representatives of minor participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawuki, J., Gatasi, G., Sserwanja, Q. et al. Utilisation of modern contraceptives by sexually active adolescent girls in Rwanda: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Health 22, 369 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01956-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01956-y