Abstract

Background

Malignant transformation of endometriosis is infrequent at the laparoscopic trocar site. Although malignant transformation is uncommon, it must be acknowledged in order to achieve radical resection.

Case presentation

We report on a 54-year-old woman with trocar site endometriosis 2 years after laparoscopic ovarian endometrial resection. Physical examination revealed a subcutaneous solid tumor with a diameter of 3 cm surrounding the scar of laparoscopic surgery in the right lower abdomen. Transabdominal ultrasonography showed a cystic tumor in the subcutaneous adipose layer of the right lower abdomen. The pathological diagnosis was poorly differentiated endometrioid carcinoma. Hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy were then performed. Histological examination revealed mixed endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma. After six cycles of chemotherapy, computed tomography showed no signs of recurrence.

Conclusions

Malignant transformation of laparoscopic endometriosis is very uncommon, and the diagnosis and stage are determined by clinical manifestations and imaging examination. The main therapy methods are radical surgery combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant radiotherapy. At the same time, reducing iatrogenic abdominal incision implantation is an effective prevention method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of endometriosis in the general population is about 10% of women of reproductive age. Endometriosis refers to abnormal growth of endometrial tissue that survives outside the uterus and occurs after cesarean section, laparoscopic surgery, hernia repair and other operations. The most common sites are rectovaginal septum, colon and vagina. The implantation of ectopic endometrium into scar tissue of the abdominal wall is called abdominal endometriosis [1]. At present, with the increase in the rate of cesarean section, the incidence of scar endometriosis has also risen. Scar endometriosis is a potential complication of cesarean section, with an incidence of about 0.03–0.45% [2, 3]. However, malignant transformation of abdominal endometriosis is very uncommon, the incidence is less than 1%, and the early diagnosis is very difficult [4]. We report a case of malignant transformation of trocar site endometriosis after laparoscopic ovarian endometrial resection, providing a scientific basis for the diagnosis and treatment of abdominal endometriosis.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 54-year-old woman who presented with a new mass on the abdominal wall scar that had grown in the past 3 months. She had a cesarean sections 31 years ago. In 2017, she underwent laparoscopic right adnexectomy for a chocolate cyst of the right ovary.

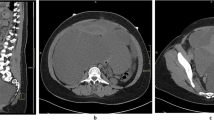

An increased abdominal mass was reported in our hospital, and physical examination revealed a subcutaneous solid tumor with a diameter of 3 cm around the scar of laparoscopic surgery on the right lower abdomen. Transabdominal ultrasound showed a cystic tumor in the subcutaneous adipose layer of the right lower abdomen (Fig. 1). Trans-vaginal ultrasonography showed normal findings.Routine laboratory findings and tumor markers (AFP, CA125, HE4 and CEA) were normal, but serums CA-199 were elevated at 41.48U/m U/mL. The patient was excised under general anesthesia. During the intraoperative exploration of the fat layer, a 3 × 2 cm mass with hard texture could be reached. After the fat was cut open, a cystic mass could be seen, in which coffee-colored fluid flowed out a poorly differentiated endometrioid carcinoma (Fig. 2). PAX-8, ER, KI-67 and CD10 were positive, while STATB2, GATA3, CDX-2 and PR were negative. Combined with the patient's history of laparoscopic surgery, ultrasound and pathological findings, it was highly suspected that the tumor was a malignant transformation of laparoscopic trocar endometriosis.

Whole-body positron emission tomography and computed tomography (18-FDG PET-CT) were performed at disease stage 14 days after surgery and showed slight hypermetabolism in the incision area. Multiple swollen lymph nodes in retrodiaphragmatic, retroperitoneal, bilateral iliac vessels and right inguinal area, abnormal metabolism.

Our patient then underwent surgical staging, laparoscopy through the peritoneum. The abdominal and renal pelvis were carefully examined, intraoperative adhesions between the greater omentum, the abdominal wall and the fundus of the uterus were observed. Tumor nodules were observed on the surface of the sigmoid colon and rectum. Right total iliac, external iliac, internal iliac, obturator lymph nodes and para-aortic lymph nodes were enlarged and fused into masses. Final pathology revealed a metastatic poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma arising from a foci of endometriosis.Tumor metastasis was observed in right pelvic lymph node and right inguinal lymph node.The remainder of the specimens were negative for malignancy.

Serum CA-125 and CA-199 increased to 36 one month after operation, 48 U/mL and 77.67U/mL, respectively. Serum CA-125 and CA-199 decreased to normal 4 months after surgery. After the operation, patients received systemic chemotherapy (6 cycles of tri-weekly liposomal doxorubicin 30 mg/m2 and carboplatin AUC = 5), which is similar to adjuvant chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer. CT scans showed no evidence of recurrence after 6 cycles of chemotherapy. Three months after 6 times of chemotherapy, she underwent repeat 18-FDG PET-CT examination, which revealed most of the original enlarged lymph nodes disappeared, with only a few small lymph nodes behind the peritoneum and low metabolism.Our patients showed no signs of recurrence 16 months after initial diagnosis,CA199, AFP, CA125, HE4 and CEA were all normal.

Discussion and conclusions

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AVE) is a relatively rare condition that normally occurs on surgical scars. All patients who have undergone pelvic surgery are at risk for this disease, which is mostly associated with cesarean section, laparoscopic surgery, followed by uterine surgery. A small number of patients with no history of abdominal surgery may also have this disease. The spread of endometrial tissue or endometriosis at the time of surgery is biologically credible because there is an opportunity to inoculate endometrial cells from hysterotomy or endometrioma into the peritoneum or abdominal wall. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis and endometriosis at the trocar site after laparoscopic surgery are extremely rare and may result from pneumoperitoneum or may result from direct contact of the excised endometriosis lesion with the abdominal wall. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis is very rare and easily overlooked by clinicians. Diagnosis is usually late, leading to missed opportunities for optimal treatment. These require us to diagnose and treat them timely and appropriately.

Histopathology

It has been reported that the most common histologic types of endometriosis are clear cell carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma, including clear cell carcinoma was 63–66.7%, followed by endometrioid carcinoma with 14.6–22% [5, 6]. Another case of mixed tumor of clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma was reported [7]. In 1925, Sampson described the malignant transformation of the first case of endometriosis, and he submitted three diagnostic criteria: (1) there is both tumor tissue and endometriosis in the tumor, (2) the histologic appearance is identical to the characteristic endometrial stroma surrounding glands, (3) there is no other primary tumor site. In addition, Scott added the fourth criterion of metaplasia between benign endometriosis and cancer in 1953, but this suggestion remains to be discussed [8]. CD10 is a reliable and sensitive (88%) immunohistochemical marker of endometrial stroma and is expressed in a small number of cytogenic chorionic cells, greatly supporting the diagnosis [9].

The etiopathogenesis of endometriosis

Recent studies have confirmed that endometriosis has many etiological variables, with genesis in genetics, epigenetic, immunology, endocrinology, and microbiome. There are some theories about the causes and pathogenesis of endometriosis: Treloar's 1999 study of the Australian population proved a 2:1 concordant ratio between identical and fraternal twins, with a corresponding genetic risk of 2.34 affecting microbial sisters. The results indicate that 51% of endometriosis is caused by genetic factors [10]. The increased risk of inheritance in first-degree relatives (5–8%) indicates polygenic and multifactorial inheritance rather than single-gene inheritance [11]. D’Alterio et al. discovered that uterine contractile force is affected by the imbalance of female genital tract (FGT) microbiota and the corresponding inflammatory response, and can increase the adhesion of relevant endometrial cells in retrograde menstruation and peritoneal cavity [12]. They also discovered higher concentrations of IL-17 in peritoneal fluid in patients with endometriosis than in patients without endometriosis.

IL-17 activates pro-angiogenic cytokines such as IL-8,—1 ß. Consequently, IL-17 plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis by promoting ectopic endometrial tissue survival, implantation and proliferation through the proliferation of blood vessels on the peritoneal surface [12]. In addition, dysfunctional natural killer cells (NK) inhibit the phagocytic activity of macrophages, clear the expression of receptors, and induce Treg lymphocytes, whose activity is inhibited so that endometrial cells can escape peritoneal immune surveillance [13, 14]. Lagana et al. found that M1 and M2 macrophages were substantially higher in the endometriosis group than in the control group. From stage I to stage IV of endometriosis, M1 macrophages gradually decrease and M2 macrophages gradually increase, which may lead to proinflammatory microenvironment disease in the early stage of inflammation and profibrotic activity in the late stage [15]. Pagliardini et al. proved that a 21 KB single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7521902 located upstream/downstream of WNT4 region has a susceptibility site for endometriosis [16]. WNT4 is also expressed at the peritoneal level and promotes the conversion of peritoneal cells to endometrial cells through a pathway that plays a part in the development of the female genital tract [17].

A GWAS investigated 7090 individual samples (2594 patients with endometriosis and 4496 healthy controls) and identified a high-risk marker for endometriosis: SNP RS3820282 located in the WNT436 gene region [18]. Sequences of the regulatory genes ESR1 and ESR2 may be the main candidate genes for the occurrence of endometriosis and ovarian cancer [18].

Clinical feature

The typical clinical manifestation of malignant transformation of abdominal endometriosis is a combination of mass, pain and circulating signs.These favorable signs are beneficial to the diagnosis, but not all cases are typical symptoms. Ivka et al. reported that these symptoms continued for eight years and were exacerbated in the last six months before surgery. More than 50% of cases have no pain connected to the menstrual cycle [19]. Ecker et al. studied 65 patients whose primary clinical manifestation was abdominal pain, with abdominal mass accounting for 73.8% and abdominal mass for 63.1% over a 12-year period [20]. Ozel et al. reported that 100% of the patients had abdominal mass. 83.3% incidence of pain, recurrent pain was 73.3%, aperiodic pain was 26.6% [21]. Scar enlargement is a common phenomenon during menstruation. Between 10 and 50% of preoperatively diagnosed cases are accurate [22, 23]. Clinically, if the symptoms such as dyspareunia or dysmenorrhea worsen or progress, especially when the realistic mass and serum HE4 level is elevated, attention should be paid to the possible progression of ovarian cancer [24]. In addition, inguinal lymph node is the most common tumor metastasis and recurrence of parts, possibly because the superficial abdominal wall lymphatic vessels located below the umbilicus flow to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes [25].

Image examination

Preoperative ultrasound, pelvic MRI and other imaging tests are important in diagnosing malignant transformation of abdominal endometriosis. The ultrasonographic appearance of AWE can vary considerably. The most common discovery is a cystic, polycystic, solid or mixed nodules close to the cesarean scar, with irregular boundary, heterogeneous texture characterized by scattered internal hyperechogenic foci, peripheral hyperechogenic ring and scanty vascularity [26]. Further MRI examination is recommended in this case. AWE usually presents as a well-defined solid or mixed mass with contrast enhancement, often accompanied by bleeding. CT examination may also be considered to preliminarily determine the benign and malignant lesions [27]. In highly suspected malignancies, PET-CT should also be used to determine disease stages.

Serum indexes and biomarkers

Currently, there is no suitable tumor marker that can predict the malignant transformation of endometriosis. In recent years, it has been reported that the serum CA125 level of patients with malignant transformation of endometriosis is normal [28,29,30]. The reasons may be as follows: (1) After the fibrosis of the malignant AWE tissue, the lesion was relatively limited and had little influence on the expression of hormones and various factors in vivo. (2) Due to the limitation of lesions, CA125 produced by ectopic endometrium is difficult to enter the blood circulation and has little influence on serum CA125. (3) The serum CA125 has low sensitivity to diagnose abdominal wall endometriosis. (4) Clinical reports show fewer cases overall, and there may be some accidents.

New data suggest that abnormal micrornas (miRNA) expression may play a part in the development of endometriosis [31]. In addition, a comprehensive analysis of miRNA expression in ovarian cancer and associated endometriosis revealed significant differences in miRNA expression [32]. These authors suggest that these miRNAs may be used as diagnostic or prognostic tools, but there is currently insufficient information about their targets, so their application in the diagnosis or treatment of endometriosis is not feasible at present. Malignant changes in endometriosis are usually hypothesized to be due to genetic mutations coupled with a relatively loose microenvironment [33]. EAOCs associated genes and signaling pathways include PTEN, CTNNB1, PIK3CA, SRC, KRAS, microsatellite instability and ARID1A [34, 35], which are known to play a crucial role in epithelial ovarian cancer relapse [36]. Loss of ARID1A expression is commonly associated with activation of the PI3K Akt pathway or amplification of XNF217, indicating an early event in the malignant transformation of endometriotic tissue to clear cell carcinoma [37]. A recent epigenetic study focused on a possible relationship between the methylation status of the promoter of the RASSF2A gene [38]. The study included 40 women who were underexpressed in both ovarian clear cell carcinoma(OCCC) and ovaria-endometrial cancer groups, and methylation status was bound up with clinical grade and stage, meaning that it may bloom into a reliable indicator of early detection. PTEN, a tumor suppressor gene significantly associated with ovarian cancer, is required to properly regulate the PI3K enzyme pathway [39]. This pathway is essential for the progression of endometriosis to ovarian cancer [40].

Pathogenesis of endometriosis transforming into cancer

The mechanism of endometriosis malignant transformation depends on multiple factors such as heredity, immunity and environment. Complex interactions among hormonal influences, immune dysfunction and inflammation may promote malignant transformation of endometriosis. Xu et al. studied 12 cases of ovarian cancer arising from endometriosis and discovered some initial genetic abnormalities on chromosomes, such as sporadic loss of heterozygosity (LOH) may enhance the susceptibility to endometriosis. Xu et al. looked at 12 cases of ovarian cancer arising in endometriosis and found that the initial genetic abnormalities on some chromosomes such as sporadic loss of heterozygosity (LOH) may increase the predisposition to endometriosis [41]. Loss of heterozygosity and further genetic changes that accumulate at more sites may lead to aggressive features leading to the malignant transformation of endometriosis into cancer. These studies suggest that the malignant transformation of endometriosis can related to molecular genetics. It was reported that 13 (62%) of 21 patients with abdominal endometriosis malignant transformation had received estrogen replacement therapy [42]. According to a recent study, pathological examination after hysterectomy showed atypical hyperplasia of endometrium, which is caused by high estrogen or no antiestrogen and may be related to malignant transformation of abdominal endometriosis [43]. Almost all types of endometriosis patients have a lot of evidence of dysfunction of immune cells: T cell reactivity and NK cell toxicity declined [44]; Polyclonal activation production of B cells and antibodies has increased [45]; peritoneal macrophages increase in number and activate [46]; the apoptosis pathway was raised and inflammatory mediators were altered [47,48,49,50]. Free hemoglobin, heme and iron that are released in large quantities into the spaces between endometriosis cyst fluid during menstruation tend to oxidize and may spontaneously convert oxyhemoglobin to metHb. ROS (O2−) is constantly produced during the oxidation of hemoglobin. Iron derivatives can also provoke Fenton reaction and promote ROS (OH) production in endometriosis cysts. In addition, hemoglobin and heme activate the expression of various antioxidant genes. Heme by combining Bach1 directly or inducing NRF2 gene stimulate the antioxidant HO1 gene expression. Antioxidants are considered double-edged swords. Excessive ROS leads to cell death. Antioxidants by eliminating active oxygen ROS (O2and ˙OH) to reduce cell death, increasing cell survival and carcinogenesis [51,52,53]. In addition, endometrial lesions may produce more reactive oxygen species, and excessive toxic reactive oxygen species in the body can lead to the damage of proteins, lipids and DNA related to oxidative stress through oncogene mutation or damage [54]. Therefore, oxidative stress may be a key factor that causes DNA damage leading to the malignant transformation of endometriosis. Due to the limited case data of malignant changes in endometriosis, the exact etiology remains to be further research.

Therapy

There is no standardized treatment regimens for this type of cancer, and the prognosis is difficult given the rarity of this type of malignancy. The consensus from case reports and reviews for both incisional endometriosis and malignant endometriosis is that complete resection of the tumor, uterus, and bilateral inguinal lymph nodes, with as wide and complete resection of the edge of the tumor and normal tissue as possible, and negative margins is optima1. After the operation, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or adjuvant radiotherapy were combined to guard against tumor relapse.

In this case, the lesion of abdominal wall endometriosis was first excised, and the pathological diagnosed low-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma of the abdominal wall after the operation. Postoperative follow-up was performed using 18-FDG PET-CT to evaluate the therapeutic effect and to determine the prognosis. Miller put forward some good prognosis factors: age under the age of 60, the tumor is small, good and without metastatic tumor differentiation, early removal of endometriosis lesions [55].

Our case is that of a postmenopausal woman, so there are no pain and periodic symptoms, only a gradual enlargement of the abdominal wall scar mass.Serum CA199 was increased and serum CA125 was normal, which was consistent with literature reports. Abdominal wall ultrasound was first performed and a cystic mass was found in the subcutaneous adipose layer of the right lower abdomen. Endometriosis was considered, but no malignant lesions were found. Due to the atypical clinical symptoms, it is very difficult to diagnose malignancy only by ultrasound examination, so we performed abdominal wall mass resection for the patient, and the postoperative pathologic diagnosis was low-differentiated endometrial carcinoma of abdominal wall.Therefore, in addition to routine abdominal ultrasound, MRI examination should also be used to determine the scope of lesions in patients with scar endometrioma.When abdominal endometriosis is not significantly improved after treatment and the mass rapidly increases, malignancy should be highly suspected and the disease stage should be determined by PET-CT examination.

In summary, malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis is a infrequent condition associated with prior pelvic surgery, which should be attached great importance when scar lesions of abdominal endometriosis develop rapidly, and should be regarded as one of the differential diagnosis of abdominal mass after laparoscopic surgery. The diagnosis and stage of disease should be confirmed by clinical feature and imaging examination, and surgical resection should be carried out in combination with oncology principles and histopathological examination, combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or adjuvant radiotherapy. Although the current treatment is mainly radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, the standardized treatment still needs further research. For most of the abdominal wall endometriosis associated with cesarean section, laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, It is a good way to prevent abdominal incision endometriosis is to reduce the cesarean section rate, protect the incision, take a specimen with an incision protection bag during the operation, reduce iatrogenic abdominal incision implantation and encourage breastfeeding to delay menstruation.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article is available from corresponding author.

Change history

29 July 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01896-7

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- CA125:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 125

- HE4:

-

Human epididymal protein 4

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CA199:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 199

- PAX-8:

-

Not applicable

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- Ki-67:

-

Not applicable

- CD10:

-

Not applicable

- STATB2:

-

Not applicable

- GATA3:

-

Not applicable

- CDX-2:

-

Not applicable

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- 18-FDG PET-CT:

-

18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- AWE:

-

Abdominal wall endometriosis()

- FGT:

-

Female genital tract

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- NK:

-

Natural killer

- M1:

-

Not applicable

- M2:

-

Not applicable

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- KB:

-

Kilobyte

- WNT4:

-

The wingless-type mammalian mouse tumour virus integration site family member 4

- GWAS:

-

Genome wide association analysis

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- ESR1:

-

Not applicable

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- EAOCs:

-

Not applicable

- PTEN:

-

Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten

- CTNNB1:

-

Catenin Beta 1

- PIK3CA:

-

Not applicable

- Src:

-

Sparse representation-based classifier

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene

- ARID1A:

-

Not applicable

- XNF217:

-

Not applicable

- RASSF2A:

-

Ras association domain family 2A

- OCCC:

-

Ovarian clear cell carcinoma

- XNF217:

-

Not applicable

- PIK3:

-

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- LOH:

-

Loss of heterozygosity

- ROS:

-

Not applicable

- NRF:

-

Not applicable

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

References

vka, Ante V, Ivan B,et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis eleven years after cesarean section: case report. Acta Clin Croat 2017;56:162–165.

Horton JD, DeZee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207–12.

Bats AS, Zafrani Y, Pautier P, et al. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis to clear cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Fertil Steril 2008;90:1197e13–16.

Stern RC, Dash R, Bentley RC, Snyder MJ, Haney AF, Robboy SJ. Malignancy in endometriosis: frequency and comparison of ovarian and extraovarian types. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:133–9.

Mihailovici A, Rottenstreich M, Kovel S, et al. Endometriosis-associated malignant transformation in abdominal surgical scar. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:1–5.

Taburiaux L, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Endometriosis-associated abdominal wall cancer: A poor prognosis? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1633–8.

Razzouk K, Roman H, Chanavaz-Lacheray I, et al. Mixed clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma arising in parietal endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2007;63:140–2.

Sampson JA. Endometrial carcinoma of the ovary arising in endometrial tissue in that organ. Arch Surg. 1925;10:1–72.

Scott RB. Malignant changes in endometriosis. Obs Gynecol. 1953;2:283–9.

Treloar SA, O’Connor DT, O’Connor VM, et al. Genetic influences on endometriosis in an Australian twin sample. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:701–10.

Deiana D, Gessa S, Anardu M, et al. Genetic of endometriosis: a comprehensive review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35:553–8.

D’Alterio MN, Giuliani C, Scicchitano F , et al. Possible role of microbiome in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Minerva Obstet Gynecol. 2021;73:193–214.

Capobianco A, Rovere-Querini P. Endometriosis, a disease of the macrophage. Front Immunol. 2013;4:9.

Wu J, Xie H, Yao S, Liang Y. Macrophage and nerve interaction in endometriosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:53.

Laganà AS, Salmeri FM, Ban Frangež H, et al. Evaluation of M1 and M2 macrophages in ovarian endometriomas from women affected by endometriosis at different stages of the disease. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36:441–444.

Pagliardini L, Gentilini D, Vigano’ P, et al. An Italian association study and meta-analysis with previous GWAS confirm WNT4, CDKN2BAS and FN1 as the first identified susceptibility loci for endometriosis. J Med Genet 2013;50:43–46.

Gaetje R, Holtrich U, Engels K, et al. Endometriosis may be generated by mimicking the ontogenetic development of the female genital tract. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:651–6.

Powell JE, Fung JN, Shakhbazov K, et al. Endometriosis risk alleles at 1p36.12 act through inverse regulation of CDC42 and LINC00339. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:5046–5058.

Sumathi VP, Mc Cluggage WG. CD10 is useful in demonstrating endometrial stroma at ectopic sites and in confifirming a diagnosis of endometriosis. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:391–2.

Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shephard JP, Lee TT. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(4):363.e1-5.

Ozel L, Sagiroglu J, Unal A, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis in the cesarean section surgical scar: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(3):526–30.

Bektas H, Bilsel Y, Sari YS, et al. Abdominal wall endometrioma: a 10-year experience and brief review of the literature. J Surg Res. 2010;164:e77-81.

Patterson GK, Winburn GB. Abdominal wall endometriomas: report of eight cases. Am Surg. 1999;65(1):36–9.

Capriglione S, Luvero D, Plotti F, T, ea al. Ovarian cancer recurrence and early detection: may HE4 play a key role in this open challenge? A systematic review of literature. Med Oncol. 2017;34(9):164.

Lengelé B, Nyssen-Behets C, Scalliet P. Anatomical bases for the radiological delineation of lymph node areas. Upper limbs, chest and abdomen. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84:335–347.

Stein L, Elsayes KM, Wagner-Bartak N. Subcutaneous abdominal wall masses: radiological reasoning. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(2):W146-151.

Randriamarolahy A, Perrin H, Cucchi JM, et al. Endometriosis following cesarean section: ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging. 2010;34(2):113–5.

Oze L, Sagiroglu J, Unal A, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis in the cesareansection surgical scar: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(3):526–30.

Omranipour R, Najafi M. Papillary serous carcinoma arising in abdominal wall endometriosis treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1347.

Yan Y, Li L, Guo J, et al. Malignant transformation of all endometriotic lesion derived from an abdominal wall scar. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115(2):202–3.

Pan Q, Luo X, Toloubeydokhti T, et al. The expression profile of micro-RNA in endometrium and endometriosis and the influence of ovarian steroids on their expression. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13(11):797–806.

Wu RL, Ali S, Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Comparative analysis of differentially expressed miRNAs and their downstream mRNAs in ovarian cancer and its associated endometriosis. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2015;7(7):258–65.

Wei JJ, William J, Bulun S. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review of clinical, pathologic, and molecular aspects. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30(6):553–68.

Ruderman R, Pavone ME. Ovarian cancer in endometriosis: an update on the clinical and molecular aspects. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(3):286–94.

Pavone ME, Lyttle BM. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: links, risks, and challenges faced. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:663–72.

Lagana AS, Colonese F, Colonese E, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of epithelial ovarian cancer’s stem cells: an overview on new diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36(5):495–505.

Ayhan A, Mao TL, Seckin T, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression is an early molecular event in tumor progression from ovarian endometriotic cyst to clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(8):1310–5.

Xia Y, Xiong N, Huang Y. Relationship between methylation status of RASSF2A gene promoter and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2018;32(1):21–8.

Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Vazquez F. Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(5):2110–5.

Anglesio MS, Bashashati A, Wang YK, et al. Multifocal endometriotic lesions associated with cancer are clonal and carry a high mutation burden. J Pathol 2015;236(2):201–209.

Xu B, Hamada S, Kusuki I, et al. Possible involvement of loss of heterozygosity in malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;120:239–46.

Munksgaard PS, Blaakaer J. The association between endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review of histological genetic and molecular alterations. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(1):164–9.

Reimnitz C, Brand E, Nieberg RK, Hacker NF. Malignancy arising in endometriosis associated with unopposed estrogen replacement. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(Pt2):444–7.

Lagana AS, Triolo O, Salmeri FM, et al. Natural killer T cell subsets in eutopic and ectopic endometrium: a fresh look to a busy corner. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(5):941–9.

Riccio LGC, Baracat EC, Chapron C, et al. The role of the B lymphocytes in endometriosis: a systematic review. J Reprod Immunol. 2017;123:29–34.

Hanada T, Tsuji S, Nakayama M, et al. Suppressive regulatory T cells and latent transforming growth factor-betaexpressing macrophages are altered in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16(1):9.

Salmeri FM, Lagana AS, Sofo V, et al. Behavior of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and tumor necrosis factor receptor 1/tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 system in mononuclear cells recovered from peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis at different stages. Reprod Sci 2015;22(2):165–172.

Sturlese E, Salmeri FM, Retto G, et al. Dysregulation of the Fas/FasL system in mononuclear cells recovered from peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;92(1–2):74–81.

Vetvicka V, Lagana AS, Salmeri FM, et al. Regulation of apoptotic pathways during endometriosis: from the molecular basis to the future perspectives. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(5):897–904.

Jorgensen H, Hill AS, Beste MT, et al. Peritoneal fluid cytokines related to endometriosis in patients evaluated for infertility. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(5):1191–9.

Kobayashi H. Potential scenarios leading to ovarian cancer arising from endometriosis. Redox Rep. 2016;21(3):119–26.

Fontana J, Zima M, Vetvicka V. Biological markers of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: After so many studies, what do we know? Immunol Investig. 2018;47(8):823–43.

Iwabuchi T, Yoshimoto C, Shigetomi H, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in endometriosis and its malignant transformation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015: 848595.

Worley MJ, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS, et al. Endometriosis associated ovarian cancer a review of pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(3):5367–79.

Miller DM, Schools JJ, Ehlen TG. Clear cell carcinoma arising in extragonadal endometriosis in a caesarean section scar during pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:127–30.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript. Literature review, paper design and manuscript writing: L H. Data collection: By Z. I solemnly declare that all authors of this manuscript have read and approved the final version submitted, and that the contents of this manuscript have not been previously copyrighted or published, nor have they been considered for publication elsewhere. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This report complies with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Institutional Ethics Committee(Human Research) of People’s Hospital of China Three Geoges University approved this study and informed consent for pubilcation of this study was obtained from the patients.

Consent for publication

The Written informed consent for publication of clinical details was obtained from the patient. A copy of the signed, written informed consent for publication form is available for review by the editor.

Competing interests

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest in this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: the affiliation of the author “Ling Han” was wrong the correct affiliation is as follows ‘Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The People’s Hospital of China Three Gorges University. The First People’s Hospital of Yichang, Jiefang Road 4, Yichang City, 443003, Hubei Province, People’s Republic of China’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, L., Zhang, B. Malignant transformation of endometriosis in a laparoscopic trocar site a case report. BMC Women's Health 22, 163 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01749-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01749-3