Abstract

Background

Existential distress is a significant source of suffering for patients facing life-threatening illness. Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies (PAT) are novel treatments that have shown promise in treating existential distress, but openness to providing PAT may be limited by stigma surrounding psychedelics and the paucity of education regarding their medical use. How PAT might be integrated into existing treatments for existential distress within palliative care remains underexplored.

Methods

The present study aimed to elucidate the attitudes of palliative care clinicians regarding treatments for existential distress, including PAT. We recruited palliative care physicians, advanced practice nurses, and spiritual and psychological care providers from multiple US sites using purposive and snowball sampling methods. Attitudes toward PAT were unknown prior to study involvement. Semi-structured interviews targeted at current approaches to existential distress and attitudes toward PAT were analyzed for thematic content.

Results

Nineteen respondents (seven physicians, four advanced practice nurses, four chaplains, three social workers, and one psychologist) were interviewed. Identified themes were 1) Existential distress is a common experience that is frequently insufficiently treated within the current treatment framework; 2) Palliative care providers ultimately see existential distress as a psychosocial-spiritual problem that evades medicalized approaches; 3) Palliative care providers believe PAT hold promise for treating existential distress but that a stronger evidence base is needed; 4) Because PAT do not currently fit existing models of existential distress treatment, barriers remain.

Conclusions

PAT is seen as a potentially powerful tool to treat refractory existential distress. Larger clinical trials and educational outreach are needed to clarify treatment targets and address safety concerns. Further work to adapt PAT to palliative care settings should emphasize collaboration with spiritual care as well as mental health providers and seek to address unresolved concerns about equitable access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Existential distress, which overlaps with the concepts of existential suffering [1], spiritual distress [2], and demoralization [3], is distress that arises for patients in the contemplation of their own mortality and is characterized by feelings of helplessness, loneliness, anxiety, and loss of meaning and purpose [4]. Existential distress has been widely recognized as a significant source of suffering for patients facing life-threatening illness (LTI) and can influence patients’ desire to hasten death or even take their own lives [5, 6]. Evidence-based treatments for existential distress remain limited: Pharmacological treatments for depressive symptoms are less effective in patients with LTI than in the general population [7] and targeted psychotherapeutic interventions demonstrate only modest benefit [8,9,10,11,12,13].

Psychedelic-assisted therapies (PAT), which apply psychotherapeutic approaches to altered states of consciousness produced by agents such as psilocybin, 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) or ketamine, may be potent treatments for patients facing existential distress in the setting of LTI. Randomized-controlled crossover trials using psilocybin have demonstrated reduced depression, anxiety and fear of death in patients with cancer- associated anxiety or depression [14,15,16], with benefits persisting in 60–80% of survivors at 6 month follow-up [14, 15]. Pilot trials with ketamine [17,18,19] and MDMA [20] suggest similar reductions in distress associated with LTI. While the evidence base still awaits larger confirmatory trials, these encouraging phase 2 results have brought discussions of psychedelic medicine into mainstream circles [21, 22] and generated proponents within palliative care [23, 24]. At the same time, stigma around psychedelics persists [25] despite their benign safety profile compared to similarly classified controlled substances [26, 27].

Whether PAT become broadly implemented within palliative care will depend not only upon the results of larger clinical trials but also the attitudes of health care providers in a position to recommend PAT. Qualitative studies of palliative care providers have identified key themes regarding attitudes toward the use of PAT in palliative settings [28, 29], as well as insights into how existential distress arises [30] and is identified by palliative care nurses [31, 32]. However, there has been little exploration into how PAT are perceived within the broader context of existential distress treatments provided by the multidisciplinary palliative care workforce. In order to provide context and direction to future work with PAT in patients with LTI, we conducted a qualitative study of palliative care providers to elicit themes regarding 1) their attitudes toward current treatments for existential distress and 2) the potential of PAT to treat existential distress associated with LTI.

Methods

Study overview and setting

We conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews with palliative care physicians, advanced practice nurses, chaplains, psychologists, and social workers currently working in palliative care settings within the United States.

Sample and recruitment

Participants were recruited via email between May 2019 and August 2020 using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling methods. Participants were not selected for knowledge about or known positions regarding PAT. Participants provided informed consent and were not directly compensated; one randomly-selected participant received an online gift card after study completion. Recruitment continued until interviews failed to reveal significant new thematic content.

Interview guide

The interview guide was developed by an interdisciplinary team including experts in palliative care (M.L.) and PAT (B.K.) and was directed at two key research questions: (1) How do palliative care providers view their role regarding existential distress and its treatment? (2) What are their attitudes toward PAT as potential treatments for existential distress in LTI? The final interview guide is available in Supplementary Materials.

Data collection

Recorded interviews were conducted by H.N. via phone, Zoom video conferencing software, or in person. Interviews ranged in duration from 32 to 52 min, and concluded once participants had responded to all sections of the semi-structured guide and had been offered the chance to extrapolate further on earlier responses. Recorded audio from each interview was transcribed using Microsoft Word and de-identified prior to qualitative analysis. After the interview, participants completed an online survey covering basic demographics, clinical setting, and health care experience.

Data analysis

Transcriptions were uploaded to Dedoose software version 8.3 and coded using a grounded theory approach [33, 34]. Initial themes were developed through open coding by M.L. and H.N., then applied to subsequent interviews by H.N and C.F. and updated in an iterative fashion following discussion and agreement of team members. Coders met regularly to resolve discrepancies and ensure adequate inter-rater agreement. Once coding was complete, study team members met to discuss grouping of codes and finalize key themes within the data [34].

Thematic validation

Themes, subthemes, and representative quotations were then sent to a subset of 5 participants for validation. Criteria for validation was ≥.78 agreement for each individual theme and subtheme.

Results

Study sample

Thematic saturation was achieved after 19 interviews. Table 1 describes participants’ demographic characteristics. No participants reported prior clinical experience with PAT. Two participants reported no prior awareness of PAT.

Thematic analysis

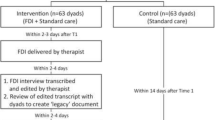

Four major themes and 15 subthemes were identified. All major themes and 13 subthemes met validation criteria, and are featured in Fig. 1. Validated themes with example quotations are displayed in Table 2.

Theme 1: existential distress is a common experience that is frequently insufficiently treated within the current treatment framework

All participants identified existential distress as an important and relevant concept for their clinical palliative care work.

Respondents described existential distress as commonly arising both in the anticipation of dying as well as in response to changes in physical and psychosocial capabilities earlier in the course of illness. Existential distress was described as a disruption of, or challenge to, pre-existing sources of meaning or valued identities. Respondents noted a relationship between existential distress and psychiatric illness, though made a clear distinction between the two.

The absence of relationships or adequate social support was linked to greater likelihood of a patient meeting difficulty in resolving existential distress. However, concern for unmet emotional, relational, or financial needs for family members was also seen as a source of distress, and LTI was noted to give rise to existential distress through the exacerbation of prior traumas and unresolved interpersonal conflicts.

Respondents also described care of patients’ families as a critical part of their clinical role, and noted challenges to identity and meaning among caregivers for those with LTI. Respondents identified their own existential distress as an occupational hazard of working with patients at the end of life.

Refractory distress was reported across all types of clinical settings. Factors associated with refractory cases included late referral to palliative care, pre-existing psychiatric illness or trauma history, and young age, especially when the patient was a young parent.

Respondents, especially those from smaller hospitals or outpatient groups, pointed to barriers including limited time for visits, absence of specialty interventions and insufficient staffing to meet patient needs. Patient resource limitations were cited as a barrier to effective treatment in all settings.

Theme 2: palliative care providers ultimately see existential distress as a psychosocial-spiritual problem that evades medicalized approaches

All respondents endorsed existential distress treatment as falling within their scope of practice, with specific roles and degree of involvement differing across professional disciplines.

Respondents described existential distress as often overlooked or treated with discomfort by medical practitioners, especially primary consulting teams and oncologists. Physician and advanced practice nursing respondents reported an absence or paucity of training on existential distress treatment prior to specialization in palliative care. Palliative care approaches to existential distress were described as contrasting with a general medical culture focused on biological models of diagnosis and treatment.

Participants endorsed therapeutic interpersonal techniques as the primary intervention for existential distress, including active empathic listening and nonjudgmental exploration of patients’ distress. More complicated cases were described as requiring specialist intervention with providers of spiritual care or psychotherapy, of which the most common types were meaning-centered, cognitive behavioral, and mindfulness-based psychotherapies. Helping patients repair or build new personal relationships was seen as integral to reducing existential distress.

Theme 3: palliative care providers believe PAT hold promise for treating existential distress but that a stronger evidence base is needed

Respondents expressed interest in expansion of research and clinical access to PAT. However, not all were enthusiastic proponents and reservations or skeptical attitudes were common.

PAT was identified as a potentially powerful addition to the palliative care “toolkit” and respondents described PAT as facilitating meaning-making by allowing patients new perspectives through which to reframe their existential struggle. Respondents endorsed the use of PAT through compassionate use provisions, describing PAT as providing hope for patients experiencing refractory existential distress. Respondents saw PAT as an alternative to controversial interventions for end-of-life distress, such as palliative sedation or physician aid-in-dying.

At the same time, participants identified the current evidence base as insufficient and cited a need for further PAT research and greater education on PAT within palliative care departments before they could feel confident in its use. Participants described PAT as late-line interventions to be used only after other therapies had failed.

Participants also expressed concerns about stigma for patients receiving PAT, as well as fears about stigmatization from other medical providers for providing PAT. Participants reported concerns that use of PAT would trigger relapse for patients with substance use disorders, and expressed worries about lasting psychological harm from dysphoric psychedelic experiences. Attitudes were more negative toward LSD and positive toward psilocybin and ketamine.

Participants expressed confidence in the safety of PAT in properly controlled settings. Respondents emphasized key safety considerations for PAT, including rigorous screening for cardiac disease or history of mania or psychosis, skilled supervision during medication-facilitated sessions, and longitudinal psychotherapy follow-up to integrate these experiences.

Theme 4. Because PAT do not currently fit existing models of existential distress treatment, barriers remain

Providers struggled to identify clearly how PAT could fit into the current treatment paradigm, with fundamental questions unanswered regarding for whom PAT might be an appropriate and accessible treatment.

There was no clear consensus around the relative benefits of delivering PAT to patients early in their course of LTI, later while admitted as inpatients, or even while on hospice. Respondents similarly failed to present clear agreement about which palliative care patients should be considered for PAT. Some described psychiatric and trauma histories as important indicators of patients who might benefit most from PAT, while others expressed concern regarding PAT for patients with any psychiatric comorbidity.

Providers described interest in PAT as concentrated within specific sociocultural groups, such as younger patients in urban settings. Respondents estimated greater interest in West Coast and Northeastern states than in the Southern US. Participants identified patient groups for whom PAT might not be appealing, such as particular religious groups, and described PAT as cost-prohibitive and likely to exclude poor and underserved communities.

Discussion

The present study reports attitudes toward the treatment of existential distress using PAT within a representative sample of palliative care professionals. PAT were seen as holding promise to improve the treatment of existential distress within palliative care settings, especially in refractory cases. Overall, respondents identified further research and outreach as necessary before PAT can be expanded in palliative care settings, and identified several unresolved barriers to implementation of PAT in palliative care settings.

Broadening the team

One of the most striking features of these interviews was the emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration within palliative care, a central cultural tenet of the field. Notably, both subthemes that failed validation touched on questions of role boundaries, and likely were rejected due to perceived violations of this core value.

“Physicians and advanced practice nurses have limited roles in the treatment of existential distress as compared to chaplains and social workers” (Theme 2) was drawn from descriptions of medical providers serving primary screening roles and triaging cases of existential distress to spiritual care or mental health care providers. However, the language of this subtheme was poorly considered, and respondents in the validation sample emphasized a team-based approach to the treatment of existential distress in which distinct roles are equally valuable.

Similarly, the second unvalidated subtheme dealt with the possibility of PAT marking a greater involvement of psychiatrists and other mental health practitioners in existential distress care: “PAT would mark a significant change in how and by whom existential distress is treated” (Theme 4). Feedback on this subtheme suggests that while respondents agree PAT would require greater involvement of psychiatrists and other mental health providers, palliative care providers would prefer to expand the umbrella of palliative care rather than referring cases to outside collaborators. This reflects the growing field of psycho-oncology and the greater incorporation of psychiatric and mental health providers into the multidisciplinary palliative care team. Furthermore, respondents reported strong interest in obtaining training in PAT within palliative care departments, despite no explicit question directed at this topic.

This study, by exploring current standards of care and attitudes toward PAT in a sample reflective of the interdisciplinary culture of palliative care, improves upon and further contextualizes recent investigations of attitudes toward PAT among palliative care providers. Those studies, which addressed perspectives of a diverse group of experts in palliative care, oncology and PAT [28] and a small sample of palliative care providers from a single department [29], described attitudes that are echoed in our broad sample of palliative care workers. Concerns regarding negative psychological experiences, hopes for a transformative new treatment, and an emphasis on larger trials to better understand risks and contraindications of PAT appear across all groups. The present study grounds discussions further in fundamental questions of how existential distress is currently treated, offering a perspective on PAT that is informed by contemporary practice and described gaps in care.

A narrow gap

Expansion of research into PAT in palliative care settings will be facilitated by the clear identification of a target population. While some participants reported an ideal of offering access to PAT for all patients facing life-threatening illness, PAT were commonly seen as intensive treatments indicated only after conventional methods have failed. Perceptions of PAT as late-line therapies may be reflective of stigma around psychedelics and thus subject to change with greater education about PAT. Still, many participants saw conventional treatments of existential distress as largely adequate, which invites us to consider the exact treatment gap PAT might fill.

The greatest need for PAT may be within populations especially likely to suffer from refractory existential distress, such as younger adults or patients with significant trauma histories. Further research would be best directed at identifying risk factors for poor response to conventional psychotherapy and spiritual counseling. Alternatively, referral to PAT could be triggered by specific shifts in the course of treatment associated with significant unmet existential needs, such as cancer recurrence, hospice enrollment, or transition from standard cancer therapies to phase I clinical trials [35].

Notably, the characteristics of patients with refractory existential distress overlapped with those of patients deemed too ill or unstable to be safely considered for PAT. Further studies are needed to clarify which psychiatric comorbidities are contraindications for PAT. Without this, the great challenge is that the window of opportunity – patients sick enough for PAT but not sick enough to be at risk of destabilization – may be narrow.

Similarly, if treatment for existential distress is more limited in less-resourced settings, PAT is not well-situated to amend this treatment gap. Even if PAT are covered by insurance, the significant time demand of treatments may perpetuate problems of power and access that continue to plague American medicine, with marginalized groups unable to benefit equitably from these therapies. Research efforts to date have failed to adequately include diverse samples, with patients of color underrepresented in PAT studies [36]. Further research is needed to determine the causes of and solutions for these disparities.

Pathways to integration

Respondents in our sample described meaning-enhancing interpersonal interventions, including both spiritual care and psychotherapeutic frameworks, as the core of conventional existential distress treatment. That meaning-making specifically mediates benefits of some conventional treatments [37] underscores respondents’ perceptions of PAT as an intervention with unique capacities to facilitate meaning-making. The capacity of psychedelic interventions to enhance personal meaning and spiritual significance is well established [38, 39]. In clinical studies, the majority of participants rate their sessions as among the top five, or even the single most, meaningful or spiritually significant experience of their lives [38] — a finding demonstrated to persist among survivors in a small, 4.5-year follow-up of PAT for cancer-related distress [40].

Our findings suggest that PAT might be most easily integrated into palliative care practice if delivered in a manner consistent with current first-line meaning-enhancing approaches of psychotherapy and spiritual counseling. As researchers explore synergies between PAT and specific therapeutic modalities in other clinical contexts [41, 42], efforts to more explicitly integrate existentially-oriented therapies such as Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy [10], Dignity Therapy [11], or Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM) [12] into preparatory and integration sessions might strengthen its efficacy as a treatment for existential distress. In order to integrate PAT into current approaches to existential distress, support of spiritual care providers in addition to secular mental health providers is paramount, and PAT researchers should include spiritual care providers within treatment paradigms when possible.

Broader collaboration between PAT and faith traditions will not be without challenges. While psychedelic agents are important sacraments for some spiritual communities [43, 44], respondents suggested the possibility that other religious and cultural groups may reject PAT due to concerns of incompatibility with established doctrine. However, participants stressed the need for individualized, patient-centered approaches to selecting therapies for existential distress, and we echo their proscriptions against ruling out inclusion by any particular group.

These findings also suggest the importance of maintaining emphasis on PAT’s meaning-enhancing effects. Psilocybin’s FDA designation as a breakthrough therapy for major depressive disorder [45, 46], while promising for the general psychiatric population, is not without pitfalls. Viewing psilocybin as a purely biological intervention that functions to boost subjective mood, as with SSRIs and ketamine, risks eliding the profound spiritual and personal meaning that patients attribute to medication-facilitated sessions and that may mediate benefits [38]. Equating PAT’s clinical benefit with the reduction of mood symptoms risks solidifying an understanding of PAT that ignores its immense potential to catalyze meaning-making for patients with LTI.

Stigma and barriers

Positive and stigmatizing views toward PAT were both common, often co-occurring within the same interview. This demonstrates the complicated way in which providers integrate new information about the therapeutic potentials of PAT with decades-old understandings of psychedelics as dangerous and illegal agents. While concerns about potential risks of PAT for patients with cardiac comorbidities echoe the exclusion criteria of recent studies, respondents also voiced concerns that do not track with recent evidence. Fears that PAT might trigger relapses among patients with substance use disorders contrasts with observations that psychedelics decrease patterns of problematic substance use in naturalistic settings [47,48,49]; PAT are being trialed as treatments for addiction [50, 51]. Similarly, concerns about persistent negative psychological effects are unsupported by the evidence. While acute anxiety during PAT is not uncommon [52, 53], there is no record of serious adverse events during modern, setting-controlled studies [54], and even those who experience transient psychedelic-related dysphoria or anxiety often go on to report these experiences as ultimately beneficial [53,54,55].

These examples highlight the importance of education to dispel longstanding misconceptions regarding carefully monitored psychedelic use and promote data-driven understandings of the risks associated with PAT. While the present study was underpowered to assess variations in knowledge and attitudes toward PAT across professional classes, further survey-based research should seek to better classify these patterns, as has been demonstrated in larger samples of psychiatrists [56] and psychologists [57].

Limitations and strengths

Convenience and snowball recruiting methods may have resulted in bias toward the cultures and institutional orthodoxies of included sites. Attitudes may be culturally specific and not necessarily generalizable outside the US. The sample of respondents was skewed toward younger and less experienced clinicians, who may be more likely to have positive views toward psychedelic therapies [56]. While the sample demonstrated minimal racial diversity, with all but one participant identifying as White/Caucasian, this may reflect broader trends in the palliative and hospice care workforce. The major strengths of this study are its broad inclusion of palliative care professional disciplines and emphasis on existing treatments for existential distress. Grounding discussions of PAT in the current standard of care offers a practically-informed model for integration into palliative care.

Conclusions

Palliative care providers describe existential distress as a common source of suffering for patients with LTI. Current treatments emphasize enhancement of sources of meaning and rely on interdisciplinary coordination. Clinicians view PAT as promising treatments for refractory existential distress, though concerns regarding access and exclusionary criteria currently limit their potential scope. Further research and education regarding psychedelic interventions are needed before PAT can be more widely adopted in palliative care settings, especially to address safety concerns and clarify a target population. Close collaboration with spiritual care and mental health providers and adaptations of PAT to existing meaning-focused approaches will facilitate integration into current practice. Educational outreach should address misconceptions regarding risks of substance use and psychological harm. Broader access to PAT research and greater diversity of study samples will improve generalizability and promote equitable treatment outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated by this project are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of responses and possibility of participant identification. De-identified data are available from the study authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LTI:

-

Life-threatening illness

- MDMA:

-

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- PAT:

-

Psychedelic-assisted therapies

References

Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: an integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41(3):604–18.

Roze des Ordons AL, Sinuff T, Stelfox HT, Kondejewski J, Sinclair S. Spiritual distress within inpatient settings - a scoping review of patient and family experiences. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;56(1):122–45.

Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, Burney S. A review of the construct of demoralization: history, definitions, and future directions for palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;33(1):93–101.

Vehling S, Kissane DW. Existential distress in cancer: alleviating suffering from fundamental loss and change. Psychooncology. 2018;27(11):2525–30.

Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, Balaguer A. The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies. Psychooncology. 2011;20(8):795–804.

Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Understanding the will to live in patients nearing death. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(1):7–10.

Ostuzzi G, Matcham F, Dauchy S, Barbui C, Hotopf M. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:Cd011006.

LeMay K, Wilson KG. Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: a review of manualized interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(3):472–93.

Grossman CH, Brooker J, Michael N, Kissane D. Death anxiety interventions in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2018;32(1):172–84.

Breitbart W, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Applebaum AJ, Lichtenthal WG, Li Y, et al. Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: a randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(15):3231–9.

Zheng R, Guo Q, Chen Z, Zeng Y. Dignity therapy, psycho-spiritual well-being and quality of life in the terminally ill: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003180.

Rodin G, Lo C, Rydall A, Shnall J, Malfitano C, Chiu A, et al. Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): a randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(23):2422–32.

Bauereiss N, Obermaier S, Ozunal SE, Baumeister H. Effects of existential interventions on spiritual, psychological, and physical well-being in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychooncology. 2018;27(11):2531–45.

Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2016;30(12):1165–80.

Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2016;30(12):1181–97.

Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, Hagerty M, McKay CR, Halberstadt AL, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):71–8.

Iglewicz A, Morrison K, Nelesen RA, Zhan T, Iglewicz B, Fairman N, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of depression in patients receiving hospice care: a retrospective medical record review of thirty-one cases. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):329–37.

Falk E, Schlieper D, van Caster P, Lutterbeck MJ, Schwartz J, Cordes J, et al. A rapid positive influence of S-ketamine on the anxiety of patients in palliative care: a retrospective pilot study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):1.

Fan W, Yang H, Sun Y, Zhang J, Li G, Zheng Y, et al. Ketamine rapidly relieves acute suicidal ideation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):2356–60.

Wolfson PE, Andries J, Feduccia AA, Jerome L, Wang JB, Williams E, et al. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of anxiety and other psychological distress related to life-threatening illnesses: a randomized pilot study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20442.

Pollan M. How to change your mind: what the new science of psychedelics teaches us about consciousness, dying, addiction, depression, and transcendence. New York: Penguin Press; 2018.

Pollan M. My adventures with the trip doctors: the researchers and renegades bringing psychedelic drugs into the mental health mainstream. New York: The New York Times Magazine; 2018.

Byock I. Taking psychedelics seriously. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):417–21.

Rosenbaum D, Boyle AB, Rosenblum AM, Ziai S, Chasen MR, Med MP. Psychedelics for psychological and existential distress in palliative and cancer care. Curr Oncol (Toronto, Ont). 2019;26(4):225–6.

Janik P, Kosticova M, Pecenak JP, Turcek M. Categorization of psychoactive substances into “hard drugs” and “soft drugs” a critical review of terminology used in current scientific literature. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(6):636–46.

Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1047–53.

Johnson MW, Griffiths RR, Hendricks PS, Henningfield JE. The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the controlled substances act. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:143–66.

Beaussant Y, Sanders J, Sager Z, Tulsky JA, Braun IM, Blinderman CD, et al. Defining the roles and research priorities for psychedelic-assisted therapies in patients with serious illness: expert clinicians’ and Investigators’ perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(10):1323–34.

Mayer CE, LeBaron VT, Acquaviva KD. Exploring the use of psilocybin therapy for existential distress: a qualitative study of palliative care provider perceptions. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2021; epub ahead of print.

Mok E, Lau KP, Lam WM, Chan LN, Ng JS, Chan KS. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of existential distress in patients with advanced cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(7):1510–22.

Keall R, Clayton JM, Butow P. How do Australian palliative care nurses address existential and spiritual concerns? Facilitators, barriers and strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(21–22):3197–205.

Fay Z, C OB. How specialist palliative care nurses identify patients with existential distress and manage their needs. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2019;25(5):233–43.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE; 2006.

Thornberg RC, Charmaz K. Grounded theory and theoretical coding. In: Flick U, editor. The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2014.

Ferrell B, Chung V, Koczywas M, Borneman T, Irish TL, Ruel NH, et al. Spirituality in cancer patients on phase 1 clinical trials. Psychooncology. 2020;29(6):1077–83.

Michaels TI, Purdon J, Collins A, Williams MT. Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):245.

Rosenfeld B, Cham H, Pessin H, Breitbart W. Why is meaning-centered group psychotherapy (MCGP) effective? Enhanced sense of meaning as the mechanism of change for advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27(2):654–60.

Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393–430.

Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, Richards BD, Jesse R, MacLean KA, et al. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2018;32(1):49–69.

Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponte KL, Guss J, et al. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2020;34(2):155–66.

Sloshower J, Guss J, Krause R, Wallace RM, Williams MT, Reed S, et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy of major depressive disorder using acceptance and commitment therapy as a therapeutic frame. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:12–9.

Heuschkel K, Kuypers KPC. Depression, mindfulness, and psilocybin: possible complementary effects of mindfulness meditation and psilocybin in the treatment of depression. A review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:224.

Halpern JH, Sherwood AR, Passie T, Blackwell KC, Ruttenber AJ. Evidence of health and safety in American members of a religion who use a hallucinogenic sacrament. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14(8):Sr15–22.

Halpern JH, Sherwood AR, Hudson JI, Yurgelun-Todd D, Pope HG Jr. Psychological and cognitive effects of long-term peyote use among native Americans. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(8):624–31.

Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;78(5):481–9.

Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, Rucker J, Watts R, Erritzoe DE, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(2):399–408.

Pisano VD, Putnam NP, Kramer HM, Franciotti KJ, Halpern JH, Holden SC. The association of psychedelic use and opioid use disorders among illicit users in the United States. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2017;31(5):606–13.

Garcia-Romeu A, Davis AK, Erowid F, Erowid E, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2019;33(9):1088–101.

Garcia-Romeu A, Davis AK, Erowid E, Erowid F, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Persisting reductions in Cannabis, opioid, and stimulant misuse after naturalistic psychedelic use: an online survey. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:955.

Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(1):55–60.

Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PC, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2015;29(3):289–99.

Anderson BT, Danforth A, Daroff PR, Stauffer C, Ekman E, Agin-Liebes G, et al. Psilocybin-assisted group therapy for demoralized older long-term AIDS survivor men: an open-label safety and feasibility pilot study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;27:100538.

Swift TC, Belser AB, Agin-Liebes G, Devenot N, Terrana S, Friedman HL, et al. Cancer at the dinner table: experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of cancer-related distress. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57(5):488–519.

Carbonaro TM, Bradstreet MP, Barrett FS, MacLean KA, Jesse R, Johnson MW, et al. Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2016;30(12):1268–78.

Malone TC, Mennenga SE, Guss J, Podrebarac SK, Owens LT, Bossis AP, et al. Individual experiences in four cancer patients following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:256.

Barnett BS, Siu WO, Pope HG Jr. A survey of American psychiatrists’ attitudes toward classic hallucinogens. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(6):476–80.

Davis AK, Agin-Liebes G, Espana M, Pilecki B, Luoma J. Attitudes and beliefs about the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs among psychologists in the United States. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2021:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2021.1971343.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emily Lodish, PsyD for providing generous feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the Source Research Foundation (SRF) to author HN. SRF had no input on study design or conduct or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.N. conducted and analyzed interviews, and was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. C.F. contributed data analysis and interpretation. B.K. assisted in study design and interview guide preparation. M.L. assisted in study design, qualitative interview training, and data analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and have approved this version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Yale University Institutional Review Board approved this study as exempt from oversight due to low participant risk, and approved waiver of written informed consent. All participants provided formal verbal consent for participation and recording. All study activities were in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki principles for human subjects research.

Consent for publication

Participants consented to publication of deidentified responses.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Semi-structured interview protocol.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Niles, H., Fogg, C., Kelmendi, B. et al. Palliative care provider attitudes toward existential distress and treatment with psychedelic-assisted therapies. BMC Palliat Care 20, 191 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00889-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00889-x