Abstract

Background

Early identification of palliative patients is challenging. The Surprise Question (SQ1; Would I be surprised if this patient were to die within 12 months?) is widely used to identify palliative patients. However, its predictive value is low. Therefore, we added a second question (SQ2) to SQ1: ‘Would I be surprised if this patient is still alive after 12 months?’ We studied the accuracy of this double surprise question (DSQ) in a general practice.

Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study with retrospective medical record review in a general practice in the eastern part of the Netherlands. Two general practitioners (GPs) answered both questions for all 292 patients aged ≥75 years (mean age 84 years).

Primary outcome was 1-year death, secondary outcomes were aspects of palliative care.

Results

SQ1 was answered with ‘no‘ for 161/292 patients. Of these, SQ2 was answered with ‘yes’ in 22 patients. Within 12 months 26 patients died, of whom 24 had been identified with SQ1 (sensitivity: 92%, specificity: 49%). Ten of them were also identified with SQ2 (sensitivity: 42%, specificity: 91%). The latter group had more contacts with their GP and more palliative care aspects were discussed.

Conclusions

The DSQ appears a feasible and easy applicable screening tool in general practice. It is highly effective in predicting patients in high need for palliative care and using it helps to discriminate between patients with different life expectancies and palliative care needs. Further research is necessary to confirm the findings of this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Timely, proactive and multidimensional palliative care has shown its beneficial effects for patients with cancer as well as for those with other life-limiting diseases [1,2,3,4,5]. The majority of people in need of palliative care are of older age [6]. This group will further increase because of an aging population. Moreover, as Bennett and all showed, older age is associated with a shorter duration of palliative care [7].

In the Netherlands, general practitioners (GPs) are important for providing palliative care at home, as they are easily accessible and they often know the patient and his context for years. However, even for GPs it is difficult to identify patients with an increased risk to deteriorate or die and hence might benefit from palliative care. Besides, GPs restrict identification of palliative patients mostly to case-finding [8, 9] and don’t systematically screen their population. As a result, palliative care nowadays mostly remains reactive, terminal care.

To help GPs and other professionals to timely identify patients in need of palliative care, several tools have been developed, [10, 11]. Most of these tools are time-intensive to apply and complex to use. Because they have different indicators per type of disease, it makes them less suitable as a generic screening instrument for daily (general) practice.

One of the instruments however, the Surprise Question (SQ1), is an easy and non-time consuming tool to apply [12]. A clinician asks himself in silence “Would I be surprised if this patient were to die in the next 12 months?” Its accuracy to predict 1-year mortality has been studied in several populations, [13, 14] but the original purpose of the SQ1 is not prognostication but identifying palliative care needs [12, 15]. Unfortunately, its specificity and prognostic accuracy vary largely; a large number of patients identified by the answer ‘no’ on SQ1 are not in need of palliative care, as many are still in an acceptable health condition. Moreover, although desirable, providing structured or specialized palliative care to all patients that are identified by SQ1 when used as a screening tool for a wider population would ask disproportionate time investments and resources.

For these reasons, we developed an additional, second Surprise Question, to be answered when SQ1 is answered with ‘no’: “Would I be surprised if this patient will be still alive after 12 months?” (SQ2). We hypothesized that adding SQ2 if SQ1 is answered with ‘no’ helps to select those patients with a high chance of deterioration or dying within 1 year, and thus are in urgent need of early palliative care. In two case vignette studies GPs considered the combination of SQ1 and SQ2, called the double SQ (DSQ), a useful tool and it triggered them to plan more anticipatory, multidimensional palliative care for those they considered most vulnerable [16, 17].

However, the DSQ has not been studied in a prospective study. In this explorative study we therefore compared the accuracy (sensitivity, specificity and predictive values) of screening patients ≥75 years in general practice with the DSQ regarding 1-year mortality to SQ1 alone, and compared health care needs and actually provided palliative care in relation to the answers on the DSQ.

Methods

Design

We performed an explorative, prospective study with a retrospective medical record review. In May 2016, two GPs (CV and WG) answered the DSQ for each included patient of their dual practice.

Participants and setting

Patients were not involved in the design of the study. Participants were two GPs in a dual practice in the Southeastern part of the Netherlands. In this practice, both GPs often have a longstanding relationship with their patients. One male GP (CV; 57 years of age, 21 years of experience) had had specialized training in palliative care, the other female GP (WG; 42 years of age, 13 years of experience as a GP) had had specialized training in elderly care.

Procedure

In 2016, both GPs together, in consensus, answered SQ1 for each patient on their patient list aged 75 years or older. If SQ1 was answered with ‘no’, they answered SQ2. By restricting identification to this age category, time investment was feasible, while selecting the majority of patients at risk of deteriorating or dying. In the Netherlands, in 2016 the mean age at death was 75.6 years for men and 80.5 years for women; 66% of the population dies at the age of 75 years or older [6]. No exclusion criteria were used. The answers were kept in a sealed envelope, not documented in the patient files and not used while planning care for patients in the following year.

Ethics

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, case number 2017–3552. In this academic GP practice, all patients have been informed that data from their medical record may be used for research; if they don’t want their data to be used for this, they can opt out. Anonymity was guaranteed. The researcher was, in her role as medical student, part of the general practice team. In the Dutch law, written informed consent for medical record review is not required.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was death at 12 months.

Next, we related the answers to the SQs to the quantity of received palliative care (secondary outcome measures 1 and 2). Besides, based on the WHO definition of palliative care that states that it should be multidimensional and proactive, [18] secondary outcome measures 3 and 4 were chosen to measure the quality of palliative care:

- 1.

Number of consultations with the GP practice (consultations at practice, home visits, telephone contacts, consultations with the practice assistant and consultations with the practice nurse);

- 2.

Number of contacts with the out of hours GP cooperation, emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalizations;

- 3.

Quality of palliative care and advance care planning (ACP). To analyze these aspects, we checked which palliative domains (somatic, social, psychological and spiritual) and patient preferences for treatment and end-of-life care (ACP directives) were discussed and documented.

- 4.

Place of death

Data collection

One year after the SQs had been answered, the medical records of all screened patients were blindly reviewed by an independent researcher (NN) who did not know the answers to the SQs.

Characteristics of all screened patients of whom medical records were available were retrieved and also analyzed per answering category group (Table 1). Of the patients that had moved and left the practice in the year after the SQs were answered, only eventual date of death was considered; for them, the secondary research questions were not answered.

One researcher (NN) extracted data from the medical records according to a case report form (Table 2). In case of doubt issues were discussed with a GP (CV) for clarification of what was written and with a non-clinical researcher (YE) for interpretation whether something occurred or didn’t occur. As a double check, the 15 files that had firstly been analyzed were re-analyzed at the end.

Of all included patients, characteristics were described (age, gender, living situation, marital status, whether receiving home care, types of diseases and whether the patient died in the 12 months after screening. For all secondary outcomes, the medical records were retrospectively analyzed for the period of 1 year after the screening. As advance care planning (ACP) could already have been performed before screening took place, we also checked the medical records on end of life preferences of the period before the screening.

Data were kept in Castor, a valid database that meets the Good Clinical Practice criteria. After all data had been extracted, the database was locked. Next, data were exported to SPSS, where the answers to the SQs were added.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS software version 22. Based on the answers to the SQs, patients were grouped in three possible answer combination groups (group 1: SQ1 answered with ‘yes’; group 2: SQ1 ‘no’, SQ2 ‘no’; group 3: SQ1 ‘no’, SQ2 ‘yes’). Descriptive statistics were used to describe characteristics of all patients and of the patients per group.

To answer the primary outcome, we related the answers to both SQs to 1-year mortality and calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV) of SQ1 and of SQ2. Sensitivity (ability to correctly identify patients who will die) and specificity (ability to correctly identify patients who will not die) were calculated, as well as the positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV: ability to respectively predict death and survival) regarding 1 year mortality for respectively SQ1 and SQ2. For each group, frequencies, means and standard deviations of the secondary outcome variables were calculated with descriptive statistics. Besides, for all secondary outcomes we analyzed if there were differences between the deceased patients with different answers to the SQs.

Results

Patients

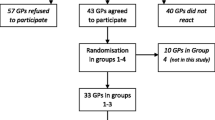

At the day of screening, 294 (15%) of the 1960 patients on the patient list were aged 75 years or older, and for 292 of them, SQ1 and SQ2 were answered by the two GPs, which took them about 3 h in total. One year later 20 patients had moved and were no longer on the patient list of the practice, and, according to the Dutch privacy law, their medical records had become inaccessible. However, information on their survival could be retrieved. Therefore, primary outcomes were based on data of 292 patients, and secondary outcomes on data of 272 patients (Fig. 1).

For 131 patients, the answer to SQ1 was ‘yes’; the GP would be surprised if these patients would die within a year (group 1). These patients had a lower mean age, more often lived at home and had less morbidities, with exception of cardiovascular disease, than patients for whom SQ1 was answered with ‘no’. SQ1 was answered with ‘no’ for the remaining 161 patients: Of these, SQ2 was answered with “no” in 139 patients (the GP would not be surprised if they would be still alive; group 2) and with ‘yes’ in 22 patients (the GP would be surprised if they would be still alive; group 3). Compared to the patients in groups 1 and 2, patients in group 3 more often received home care and more often were diagnosed with cancer or organ failure.

Deaths – primary outcome

In total 26 patients died during the year of study, of whom two, who both died unexpectedly, had not been identified with SQ1 (SQ1 = no) (sensitivity SQ1: 92%). The specificity of SQ1 was 49%. Of the 161 patients identified with SQ1, 24 died (PPV SQ1: 15%). The negative predictive value (NPV) of SQ1 was 99% (Table 3).

Ten of the deceased patients had been identified with SQ2 (SQ2 = yes), 14 had not (sensitivity SQ2: 42%). The specificity of SQ2 was 91%. With SQ2, 22 patients had been identified, of whom ten had died (PPV SQ2: 45%). The NPV of SQ2 was 90% (Table 3).

After a year, 46% of the patients in group 3 had died, compared to 10% of the patients in group 2 and 2% of the patients in group 1.

Secondary outcomes

Consultations with GP

The mean number of contacts (all types) with the GP was lowest for group 1 and highest for group 3 (group 1: 6.13; group 2: 11.14; group 3: 13.05).

Out of hours GP cooperation, ER visits, hospitalizations

The mean number of contacts with the out of hours service was 0.25 in group 1, 0.77 in group 2 and 1.29 in group 3. No large differences in number of ER visits and hospitalizations were found (Table 4).

Palliative care provision

Regarding the documentation of palliative care aspects, figures were almost always highest in group 3 and lowest in group 1 (Table 5). Existential issues were discussed with 57% of the patients in group 3, with 32% of the patients in group 2 and with only 18% of the patients in group 1. Advance care planning was done most often in group 3 (52% versus 34% in group 2 and 20% in group 1) and in the majority of the patients in group 3 (81%), advance care planning often had already been started before the screening with the SQs.

Discussion

Summary

In this study, we investigated the outcome of the Double Surprise Question (DSQ): adding SQ2 to SQ1 if SQ1 is answered with ‘no’, as a proactive screening tool for palliative care needs in primary care. We found a low specificity of SQ1, meaning that many patients were incorrectly identified. For SQ2, we found a low sensitivity, which means that more patients were missed. Therefore each of both SQs on its own is inaccurate in predicting death. However, by asking both questions, a division into three groups was made with largely different death rates (highest in group 3 (SQ1: no, SQ2: yes) and lowest in group 1 (SQ1: yes). Furthermore, patients in group 3 had more contacts with the GP and the out of hours GP service, and aspects of palliative care and advance care planning were more often discussed with these patients than with patients in groups 1 and 2. Patients in group 1 had the lowest figures for these outcomes.

Our findings suggest that the DSQ discriminates between patients with different life expectancies and care consumptions, and also show that SQ2 complements SQ1. The differences in provided care between the two answering categories of SQ2 (group 2 versus group 3), but also between the two categories of SQ1 (group 1 versus groups 2 plus 3 together), show that SQ2 cannot replace SQ1; SQ1 and SQ2 are meant to be applied together.

Because of the clear differences between the three groups, the answers to the DSQ seem related to palliative care needs, although we realize that care needs are not equal to care consumption. In general practice, it is not feasible to provide proactive palliative care to all patients identified with SQ, because of time constraints. Moreover, providing proactive palliative care to patients not in need of it is undesirable for patients and GPs.. SQ2 however divides those patients selected with SQ1 in a small group to focus proactive palliative care on, and a larger group to monitor less intensively.

Strengths and limitations

The DSQ is a simple, innovative, and easy applicable screening tool with the potential to predict individual death and palliative care needs of older patients in daily general practice. It offers the possibility to improve the correct identification of palliative patients. With our study design, we were able to gain information about its properties, taking other outcomes than 1-year mortality in account. While planning care for their patients, the GPs were therefore not actively influenced by the answers to the SQs, although there is a chance that the GPs could recall the small number of patients in group 3 which might have influenced the results. However, if this was the case, to our opinion this recalling of the patients in group 3 will be more related to the frail condition of these patients than to the answers to the SQs. In this prospective study we were able to screen in the whole population elderly, with a high prevalence of death and palliative care.

However, this study has also some limitations. This explorative study was performed in one general practice, where both GPs have been extensively trained in respectively palliative care and frail elderly care and are familiar with both SQs, and are both authors of this paper. This might have influenced the findings.

Next, we studied the DSQ in patients aged 75 and older, implying that we have no information on its value for younger patients.

Almost half of the patients in group 3 died during the year. This means that they had less time to have had contacts with the GP. If they had lived the entire year, they probably would have had more contacts. This may have led to an underestimation of the quantity and also quality of care in group 3.

Comparison with existing literature

Over the past decade, studies on the original SQ (SQ1) in different settings and in different patient groups were always limited to prognostication of death. However, palliative care needs are not always linked to prognosis. The original aim of SQ1 was to identify if a patient is thought to benefit from palliative care services [12] and not to determine if a patient is likely to die in the next year. Our study is the first to study other proxies for palliative care needs as well. Next, up to now the value of SQ1 has been mainly studied in hospital settings or in patient groups with specific, advanced diseases. The only exception is a study of Mitchell et al., who also studied SQ1 as a screening tool in elderly patients in general practice [19]. Finally, this is the first time that the DSQ has been studied prospectively.

Recent meta-analyses showed large ranges in sensitivity and specificity of the individual SQ1 for different studies in homogeneous populations [13, 14]. However, in a daily clinical primary care practice, both high sensitivity and a high specificity are needed to identify the individual patients with a high certitude to die in the coming year, in order to adapt proper care planning in the high through put practice of the future.

Some criticisms at the use of SQ1 as a screening tool have been expressed [20,21,22]. Because of its moderate predictive values for death, the limited research in patients with non-cancer disease and the lack of evidence that a negative answer to SQ1 correlates with palliative care needs, resistance against its prominent position in extensive screening tools for palliative needs and in palliative care guidelines have been raised. Within this study, we screened all elderly and included other proxies for palliative care needs, thereby providing more information about the properties of SQ1, and also of SQ2.

Conclusions

The DSQ is an innovative, easy and fast screening tool with the potential to predict individual death and palliative care needs of (older) patients in daily general practice as it divides the patient population into three groups with different life expectancy and care consumptions. Further research is necessary to confirm the findings in this explorative study.

Using the DSQ is not meant to predict survival, but to trigger GPs to think about the condition of the patient and to use this awareness while planning and providing palliative care [1, 23, 24].

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request via the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACP:

-

Advance Care Planning

- DSQ:

-

The Double Surprise Question

- ER:

-

Emergency Room

- GP(s):

-

General Practitioner(s)

- NPV:

-

Negative Predictive Value

- PPV:

-

Positive Predictive Value

- SQ1:

-

The Surprise Question

- SQ2:

-

The second Surprise Question

- SQs:

-

Surprise Questions

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative Care for Patients with metastatic non–Small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Bakitas M, Lyons K, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the project enable ii randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–9.

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD007760. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2.

Sidebottom AC, Jorgenson A, Richards H, Kirven J, Sillah A. Inpatient palliative care for patients with acute heart failure: outcomes from a randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):134–42.

Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, Gao W, Gysels M, Dzingina M, et al. An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(12):979–87.

CBS. Dutch Mortality Figures 2018. [Available from: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/en/dataset/37979eng/table?ts=1511452762338.

Bennett MI, Ziegler L, Allsop M, Daniel S, Hurlow A. What determines duration of palliative care before death for patients with advanced disease? A retrospective cohort study of community and hospital palliative care provision in a large UK city. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e012576.

Thoonsen B, Vissers K, Verhagen S, Prins J, Bor H, van Weel C, et al. Training general practitioners in early identification and anticipatory palliative care planning: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:126.

Abarshi EA, Echteld MA, Van den Block L, Donker GA, Deliens L, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Recognising patients who will die in the near future: a nationwide study via the Dutch sentinel network of GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(587):e371–8.

Maas EA, Murray SA, Engels Y, Campbell C. What tools are available to identify patients with palliative care needs in primary care: a systematic literature review and survey of European practice. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(4):444–51.

Walsh RI, Mitchell G, Francis L, van Driel ML. What diagnostic tools exist for the early identification of palliative care patients in general practice? A systematic review. J Palliat Care. 2015;31(2):118–23.

Lynn J. Living long in fragile health: the new demographics shape end of life care. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005;Spec No:S14-8. https://doi.org/10.1353/hcr.2005.0096.

Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Adhikari NK. The "surprise question" for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2017;189(13):E484–e93.

White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P. How accurate is the ‘surprise question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):139.

Romo RD, Lynn J. The utility and value of the "surprise question" for patients with serious illness. CMAJ. 2017;189(33):E1072–E3.

Weijers F, Veldhoven C, Verhagen S, Vissers K, Engels Y. Does adding a second surprise question to case vignettes help GPs to increase the thoroughness of palliative care planning? Results of a pilot RCT; 2017.

Klok L, Engels Y, Veldhoven C, Rotar PD. Early identification of patients in need of palliative care in Slovenian general practice; 2017.

WHO. Definition of palliative care 2002. [Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

Mitchell GK, Senior HE, Rhee JJ, Ware RS, Young S, Teo PC, et al. Using intuition or a formal palliative care needs assessment screening process in general practice to predict death within 12 months: a randomised controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2018;32(2):384-394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317698621.

Janssen DJA, Beuken-van Everdingen vd, M.H.J., Schols JMGA. Verrast door de ‘surprise question’. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2015;159:A8427.

Small N, Gardiner C, Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, Seamark D, et al. Using a prediction of death in the next 12 months as a prompt for referral to palliative care acts to the detriment of patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med. 2010;24(7):740–1.

Bodkin H. ‘Surprise question’ sees thousands wrongly told they will die under faulty NHS system. The Telegraph; 2017.

Denvir MA, Cudmore S, Highet G, Robertson S, Donald L, Stephen J, et al. Phase 2 randomised controlled trial and feasibility study of future care planning in patients with advanced heart disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24619.

Duenk RG, Verhagen C, Bronkhorst EM, van Mierlo P, Broeders M, Collard SM, et al. Proactive palliative care for patients with COPD (PROLONG): a pragmatic cluster controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2795–806.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

We did not receive any funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMMV initiated the idea for SQ2 and this study, supervised medical record review, developed the protocol. NN performed the medical record review, analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft of the paper. WDG was involved in data collection and interpreting the data. CAHHVMV and NN wrote the initial draft of the paper, to which all the authors contributed. YE was involved in study design, data collection, analysis, and co-writing the paper. She also supervised the entire study. SV, HS and KCPV were involved in development of the protocol and the writing process, and all authors had access to all data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, case number 2017–3552.

In this academic GP practice, all patients have been informed that data from their medical record may be used for research; if they don’t want their data to be used for this, they can opt out. Anonymity was guaranteed. The researcher was, in her role as medical student, part of the general practice team. The research ethic committee applied a combination of 3 Dutch laws regarding privacy and medical anonymity (the Algemene Verordening Gegevensbescherming AVG (https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0040940/2018-05-25), Wet op de Geneeskundige Behandelingsovereenkomst WGBO (https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/rechten-van-patient-en-privacy/rechten-bij-een-medische-behandeling/rechten-en-plichten-bij-medische-behandeling) and Wet Maatschappelijke Ondersteuning WMO (https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/zorg-en-ondersteuning-thuis/wmo-2015) in the approval process of the study, which included the permission not asking written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

YE is a member of the editorial board (Associate Editor) of this journal, but the editorial board had no role in the editorial process of this manuscript. No support from any organisation for the submitted work.

No financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

No other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Veldhoven, C.M.M., Nutma, N., De Graaf, W. et al. Screening with the double surprise question to predict deterioration and death: an explorative study. BMC Palliat Care 18, 118 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0503-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0503-9