Abstract

Background

Limiting treatment forms part of practice in many fields of medicine. There is a scarcity of robust data from Germany. Therefore, in this paper, we report results of a survey among German physicians with a focus on frequencies, aspects of decision making and determinants of limiting treatment with expected or intended shortening of life.

Methods

Postal survey among a random sample of physicians working in the area of five German state chambers of physicians using a modified version of the questionnaire of the EURELD Consortium. Information requested referred to the patients who died most recently within the last 12 months. Logistic regression was performed to analyse associations between characteristics of physicians and patients regarding limitation of treatment with expected or intended shortening of life.

Results

As reported elsewhere, 734 physicians responded (response rate 36.9%) and of these, 174 (43.2%) reported a withholding and 144 (35.7%) a withdrawal of treatment. Eighty one physicians estimated that there was at least some shortening of life as a consequence. In 25.9% of these cases hastening death had been discussed with the patient at the time or immediately prior to this action. Types of treatment most frequently limited was artificial nutrition (n = 35). Bivariate analysis indicates that limitation of treatment with possible or intended shortening of life for patients aged > 75 years is performed significantly more often (p = 0.007, OR 1.848). There was significantly less limitation of treatment in patients who died from cancer compared to patients with other causes of death (p = 0.01, OR 0.486). There was no significant statistical association with physicians’ religion, palliative care qualification or frequencies of limiting treatment.

Conclusions

In comparison to recent research from other European countries, limitation of treatment with expected or intended shortening of life is frequently performed amongst the investigated sample. The role of clinical and non-medical aspects possibly relevant for physicians’ decision about withholding or withdrawal of treatment with possible or intended shortening of life and reasons for non-involvement of patients should be explored in more detail by means of mixed method and interdisciplinary empirical-ethical analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Limiting treatment, in the sense of withholding and/or withdrawal of medical measures, is part of clinical practice across different fields of medicine [1–5]. At the same time, there is considerable variation in frequency. More than a decade ago, the EURELD study, for example, showed a frequency of 4% in Italy, while physicians in Switzerland reported limitation of treatment in 28% of cases [6]. In addition, there have been changes observed over time with regard to the frequency of these decisions [1, 7, 8].

Although accepted in many jurisdictions, limitation of treatment is still challenging for physicians [9–11]. There is evidence that decisions about the intensity of treatment in patients near the end of life vary considerably and that these variations cannot be explained fully by medical factors [12–14]. Qualitative studies [15] and survey research suggest that physicians’ values and other non-medical factors contribute to the variation in practice [16–18].

While the practice of limiting treatment has been researched in several countries [1, 19, 20], there is a scarcity of robust data in Germany. Parts of the data gathered in Germany more recently are difficult to interpret due to the vague terminology used for capturing the different end-of-life practices [21]. Other studies are limited to particular clinical fields, such as palliative care, intensive care or oncology [3, 22–24]. Furthermore, some of the data on limitation of treatment near the end of life available were gathered almost two decades ago [25, 26]. In the light of the changes regarding the ethico-legal framework for decisions at the end of life [27], it is possible that the frequency of (some of the end-of-life practices) or reporting of the practice changes over time. This might be particularly the case given the fact that limitation of treatment with possible shortening of life has gained particular scientific and public interest in Germany in the course of the debate about legislating advance directives. While the German courts had confirmed patients’ right to reject treatment decades ago, legislation which confirms patients’ right to limit any treatment in advance has only been in existence since 2009.

The right of a patient to reject treatment is an important normative cornerstone. However, decisions about limiting treatment are often discussed in daily clinical practice in situations in which patients are open to more treatment, but in which the benefit and harm of specific treatment needs to be evaluated critically. In addition to the clinical challenge to determine benefit and harm in the light of frequent absence of evidence in such situations, there are also ethically relevant challenges. How far physicians can evaluate the benefit and harm of treatment without taking into account the subjective perspective of the patient, for example, is a matter for debate.

Data about frequencies and characteristics of decisions about limiting treatment and the decision-making process are important to identify challenges and to inform guidance on good clinical practice with regard to these decisions. The data which has been elicited in representative studies in various countries [1, 6–8, 28, 29] cannot necessarily be transferred to the situation in Germany. This is because country-specific, cultural and legal differences may not only influence the findings, but also the interpretation of findings regarding guidance on good clinical practice concerning limiting treatment.

The aim of this paper is to provide an in depth empirical analysis of practices of treatment limitation. We present findings on limiting treatment collected in a survey of physicians in five state chambers of physicians in Germany in 2013. The analysis focuses on those practices in which responding physicians expected or intended shortening of life. The empirical findings will be interpreted in the light of available international survey research and with reference to ethical and legal standards relevant for decisions about withholding or withdrawal of treatment in Germany.

Methods

Participants and mailing procedure

The authors conducted a postal cross-sectional survey on end-of-life practices among a random sample of 2,003 physicians from five German state chambers of physicians (Westphalia-Lippe, North Rhine, Saarland, Saxony and Thuringia), which cover around a third of all physicians working in Germany. The methods and first findings regarding the range of different end-of-life practices have been published elsewhere [30]. In line with the procedure approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Ruhr-University Bochum (AZ 4196–11) there was no identifying code on the questionnaire for the protection of anonymity. Physicians received the questionnaire and a leaflet with information on purpose, potential benefits and risks of the study as well as research procedure for the first time in the second calendar week of 2013. Consent was taken for granted when physicians returned the questionnaire anonymously. All physicians received a reminder and a second questionnaire in calendar week four, together with the information that only one questionnaire should be returned by each physician. Due to the procedure, it was not possible to conduct a non-responder analysis.

Questionnaire

We used a modified version of the EURELD questionnaire, which had already been used in the German-speaking part of Switzerland [6] and in an earlier study on end-of-life practices of German palliative care physicians conducted by the second and last author of this paper, as the survey instrument [3, 22]. Changes that were made were distinctions of questions on actions from expected or intended effects [31] and three additional questions on physicians’ views of assisted suicide. Following the procedure described by Seale [31], potential participants had been informed on the first page of the questionnaire that all questions of the survey instrument refer to the patient who had most recently died under their care. Participants of the study who indicated on the cover page of the questionnaire that they had not cared for a dying patient within the last 12 months were asked to return the questionnaire with information only on their views on assisted suicide and socio-demographic aspects. Completed questionnaires were sent to a scientific institute for social research which recorded the data in a SPSS data file to avoid any direct contact between respondents and researchers. The relevant key questions can be found in Table 1.

Analyses

The raw data entry was double-checked within this institution. In addition, the plausibility of the data entered was checked by the first author. Free text comments regarding the type of treatment that had been limited were categorised by the first author together with the last author by means of a modified categorical system of different types of treatment which had been used in earlier research [3, 29]. Table 2 indicates the different steps of the analysis and the respective sample.

The results of the descriptive analysis of end-of-life practices are provided as total numbers and valid percentages for the total sample or subgroups. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 for Windows. We explored associations between the limitation of medical treatment and characteristics from the side of the patient or the physician based on findings of earlier surveys [29, 32]. This included the possible influence of patients’ age [3, 33, 34], disease [3, 35], physicians’ religious affiliation [16] and specialisation in palliative care [3] with regard to limiting treatment with possible and/or intended shortening of life using binary logistic regression. Our hypotheses were as follows: a) treatment limitation with possible or expected shortening of life is performed more often in patients of older age; b) treatment limitation with possible or expected shortening of life is performed less often in patients dying from cancer; c) physicians who describe themselves as religious perform less treatment limitation with a possible or expected shortening of life than physicians who are non-religious; and d) physicians with a specialisation in palliative care perform treatment limitation with a possible or expected shortening of life more often than other medical specialists. Binary logistic regression was used to explore bivariate relationships between the dependent variable ‘treatment limitation with possible and/or intended shortening of life’ and four independent variables: (1) dichotomised patient’s age ≥ 75 years, (2) patient dying from cancer, (3) physician being religious, and (4) physician’s specialisation in palliative medicine. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. Subsequently, a multivariable logistic regression was performed with the aforementioned categories in one block using the enter method. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

As reported elsewhere [30], a sample of 734 respondents (response rate 36.9%) was obtained. A total of 403 physicians within this sample had cared for an adult patient who died within the 12 months prior to the survey. Of those physicians who had cared for a patient near the end of life, 219 (54.34%) reported a limitation of treatment. Of these, 174 (43.2%) reported a withholding and 144 (35.7%) a withdrawal of treatment (doctors could have both withheld and withdrawn treatment in the same patient). In the following, we report unpublished data of an in-depth analysis of determinants for limiting treatment and characteristics of the decision-making process.

Types of limited treatment and expected consequences regarding shortening of life

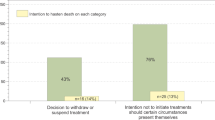

Withholding or withdrawing of treatment with a possible or intended shortening of life was performed in 144/403 cases (35.7%). 135 physicians (33.5%) have performed a treatment limitation with a possible shortening of life and 19.1% (n = 77) with the explicit intention to shorten life (doctors could have had ambivalent intentions). As mentioned in the methods section and due to the structure of the questionnaire, details of decisions about withholding or withdrawal of treatment could only be further analysed if respondents indicated this type of end-of-life practice as the last in a row of several practices (e.g. symptom alleviation, assisted suicide) on the questionnaire. Accordingly, we could analyse in more detail the data of 75 patients for whom treatment limitation with intended shortening of life and 29 patients for whom limiting treatment with possible shortening of life (but no respective intention) was reported (step 2 of analysis; see method section). The characteristics of the 104 physicians who limited treatment and respective patient characteristics can be found in Tables 3 and 4.

Out of the subsample defined above, 41 physicians of the 104 respondents (40.6%) estimated the shortening of life as a consequence of limiting treatment to be between 1 and 7 days. A total of 20 physicians (19.8%) estimated that there was no shortening of life in the concrete patient as a consequence of their action. In ten cases (9.9%), shortening of life was estimated to be between 1 and 6 months. In this group, it was reported that six patients had died from cancer, two from cardiovascular diseases and two from other or unknown diseases. Table 5 summarises the findings on estimated shortening of life as a consequence of limiting treatment. The types of treatment limited most frequently were artificial nutrition (n = 35), antibiotics (n = 33) and the administration of catecholamines (n = 27). Table 6 summarises the data reported on types of treatments which had been withheld or withdrawn.

Decision-making and patient involvement

Eighty one physicians estimated that there was at least some shortening of life as a consequence of the limitation of treatment (see Table 5). This sample is a subgroup of the cases with intended or possible shortening of life (n = 104) reported above. A total of 21 of the physicians in this subsample (25.9%) reported that hastening death as a possible or intended consequence of limiting treatment had been discussed with the patient at the time or immediately prior to this action (see Table 7). In 23 cases (28.4%), the action was discussed with the patient some time before. In 37 cases (45.7%), the estimated hastening of death due to the limitation of treatment performed was not discussed with the patient at all. In 29 of these cases (78.4%), the patient was considered as not able to evaluate his/her situation and make an adequate decision about it at all by the physician.

In six cases (16.2%), the patient was judged as not entirely able to evaluate his/her situation. In two cases (5.4%), the patient was judged able to evaluate the situation properly. In one of these cases, “dementia” was given as a reason for not discussing hastening of death, in the other, no specific reason was indicated for not discussing limitation of treatment with hastening death as a possible consequence.

Determinants associated with limitation of treatment and expected shortening of life

Based on our hypotheses (see method section), we investigated possible associations between patient disease (cancer versus non-cancer), age and physicians’ religious affiliation and specialisation in palliative medicine with frequencies of limiting treatment with shortening life. Bivariate analysis shows that age ≥ 75 years is significantly associated with limiting treatment with a possible and/or intended shortening of life (p = 0.007, OR 1.848, CI [1.183;2.886]). However, this association could not be affirmed in multivariable regression which included patient disease (cancer versus non-cancer), physicians’ religious affiliation and specialisation in palliative medicine (p = 0.205, OR 1.432, CI [0.822;2.496]). Compared to patients dying from other diseases, limitation of treatment at the end of life in patients dying from cancer was performed significantly less often (bivariate analysis: p = 0.000, OR 0.409, CI [0.261;0.64], multivariable analysis: p = 0.01, OR 0.486, CI [0.281;0.84]). There were no statistically significant differences regarding the performance of treatment limitation between physicians with and without religious affiliation (bivariate regression: p = 0.951, OR 0.984, CI [0.581;1.666], multivariable regression: p = 0.829, OR 1.072, CI [0.572;2.011]). There was also no significant association between the physician being specialised in palliative care and limiting treatment with possible or intended shortening of life (bivariate regression: p = 0.440, OR 0.742, CI [0.348;1.583], multivariable regression: p = 0.727, OR 0.866, CI [0.386;1.943]). Table 8 summarises the findings of bi- and multivariable logistic regression analysis regarding the association of socio-demographic factors of patients and physicians with a prevalence for limiting treatment with possible or intended shortening of life.

Discussion

This paper provides in-depth analyses of practices and decision-making about limiting treatment of German physicians in those cases in which shortening of life was expected or even intended by the treating physician. The study contributes data elicited with an internationally widely used survey instrument [6, 8, 29] from a sample of German physicians who work in different clinical fields. In the following, we will compare the findings with data elicited in other countries and analyse the results against the background of current ethical and legal guidance in Germany.

Frequency of limiting treatment

Practices of limitation of treatment with intended or possible shortening of life in our sample are the second most frequent decisions at the end of life (n = 144, 35.7%). Withholding or withdrawal of medical measures with intended or possible shortening of life takes place less often than alleviation of symptoms (n = 299, 86.7%), but more often than “palliative sedation” (n = 105, 30.8%) or the much discussed practices of physician-assisted suicide (n = 1, 0.3%) and euthanasia (n = 2, 0.6%) [30]. Given that the survey instrument, similar to the study from Seale [36], clearly distinguishes questions on the actual practice (e.g. withholding or withdrawing) from actions with expected consequences or the intention of the physician (i.e. shortening of life), we believe that the survey instrument avoids misunderstandings and that the figures gathered are robust [37, 38]. Compared to the study published by Seale in 2009 [36], treatment limitation with intended shortening of life (19.1 vs. 7.4%) as well as with possible shortening of life (33.5 vs. 28.9%) was practiced more frequently in our sample. Moreover, our figures are comparable to data published recently by Bosshard et al. in Switzerland [7] as well as the data presented by Onwuteaka et al. in the Netherlands [8]. Compared to the data published by Chambaere et al. [1] withholding and withdrawing of life-prolonging treatment was performed more frequently in our sample. However, the latter three studies do not distinguish between data about the practice (“limiting treatment”) and the practice combined with a consequence (“limiting treatment with possible shortening of life”) which means that comparison is limited. In addition, the differences in methodology such as the chosen approach to physicians based on death certificates signed by the respective physicians in the aforementioned three studies should be considered as a factor relevant for the reported differences.

Moreover, our results have to be interpreted with caution due to potential selection bias in a sample in which more than 60% of physicians did not respond. One explanation for the relatively high rate of limiting treatment may be an increased awareness of the possibility of limiting treatment lawfully in Germany if this is in accordance with the patients will. Debates around the legislation of advance directives (enacted) and the more recent debate about a law on assisted suicide (enacted in 2015) during which the normative framework for limiting treatment at the end of life has been reiterated in many scientific and popular articles may be triggers for such an increased awareness. In this respect the reported high numbers of limiting treatment could be interpreted as positive effects of the debate in the sense of an increased awareness amongst physicians that limiting treatment is an essential part of high quality care at the end of life.

Decision-making and patient involvement

How far patients are involved in decisions about limiting treatment with associated shortening of life is of particular interest from a clinical-ethics perspective. This is because the normative evaluation of benefit and harm of a treatment against possible shortening of life is a matter which varies according to personal values and preferences. Accordingly, the involvement of patient in such evaluation can inform a decision which takes into account the patients’ personal stance. The responses of the physicians indicate that in about half of the cases, decisions about limiting and the consequence of possible or intended hastening death had been discussed with the patient at least some time prior to the actual limiting of treatment. Evidence indicates that the time of discussing end-of-life issues depends on perceived competences and further characteristics from the side of the physician [39, 40]. In the group in which there had not been a discussion with patients, this has been explained by the respondents with reference to the physicians’ judgment that the patient was deemed not able to make a competent decision. The high number of cases in which decisions about limiting treatment with shortening of life are being made on behalf of incompetent patients point to the importance of communicating options and preferences early, as this is advocated by proponents of advance care planning [41, 42] which has been recently incorporated as part of the German legislation on hospice and palliative care (Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Hospiz- und Palliativversorgung in Deutschland, 8.12.2015).

Clinical and non-medical determinants in limiting treatment

The statistical analysis of determinants associated with decisions about limiting treatment with possible or intended shortening of life confirms, as part of the bivariate analysis, earlier findings that there is significantly more limiting of treatment with possible and/or intended shortening of life in older patients [3, 33, 34]. However, logistic regression also indicates that there are further factors possibly relevant to these decisions. The relatively high number of (younger) cancer patients in the sample in whom there is significantly less treatment limitation may be a confounding factor responsible for the fact that the association between age and treatment limitation could not be confirmed in the multivariable analysis. From a clinical perspective, a higher prevalence of treatment limitation in elderly patients is of little surprise, since older age is often associated with a worse health condition which restricts treatment options. Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence for the effects of treatment in elderly patients, since these patients are often underrepresented in clinical research [43]. However, quantitative and qualitative research raise questions whether “biological age”, in the sense of fitness, is the only reason for treating elderly patients less intensively. Findings from qualitative interviews with oncologists in Germany and the UK suggest that images or stereotypes of the situation of younger or elderly patients may influence decisions about offering or limiting cancer treatment [18, 44]. There may be a risk of both overtreatment of younger as well as undertreatment of older patients if health professionals do not reflect that the evaluation of life situations of younger or older patients may be value-laden. Our research did not confirm our hypotheses regarding the influence of the physicians’ religious affiliation or specialisation in palliative care with the frequency of this practice. Regarding the possible influences of the religion of the physician, our findings seem to be in contrast with those of Seale [16], who found that doctors who described themselves as non-religious more often made decisions with foreseen or intended ending of life. However, one explanation for this difference may be that our survey instrument did not explicitly investigate perceived religious attitudes, but only formal affiliation. With regard to the lack of an association between limiting treatment and physicians’ additional qualification in palliative care, one explanation is the low number of physicians in our sample who had such a qualification (n = 33) and the over-representation of patients with cancer.

Limitations and strengths

The refusal of the majority of the state chambers of physicians to draw a random sample for this study and the low response rate of 36.9% are limitations with regard to the representativeness of the sample of physicians participating. Another limitation is the possible misunderstanding of single questions given the complex topic surveyed in this study [11]. Further limitations encompass socially desirable answers and recall bias. A strength of the study is the use of an internationally widely used instrument with a language which avoids misleading terms, such as “passive euthanasia”. Furthermore, the study is not limited to selected fields, but reports findings from across different clinical practices. Finally, the interpretation of data is a result of multidisciplinary work involving philosophers, health researchers and authors with clinical experience in end-of-life care.

Conclusions

Limitation of treatment with expected and intended hastening death is, compared to international research, frequently practiced in this sample of German physicians. Clinical aspects (i.e. cancer) and socio-demographic characteristics on the side of patients, for instance, seem to influence decisions about limitation of treatment with associated shortening of life. To be able to understand how far these factors influence decisions about limiting treatment with associated shortening of life using an empirical mixed-method approach, it is important to combine empirical research with conceptual analysis rooted, for example, in ethics or sociology.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Chambaere K, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, Cohen J, Deliens L. Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1179–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1414527.

Lesieur O, Leloup M, Gonzalez F, Mamzer M. Withholding or withdrawal of treatment under french rules: a study performed in 43 intensive care units. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:56. doi:10.1186/s13613-015-0056-x.

Schildmann J, Hoetzel J, Baumann A, Mueller-Busch C, Vollmann J. Limitation of treatment at the end of life: an empirical-ethical analysis regarding the practices of physician members of the German society for palliative medicine. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:327–32. doi:10.1136/jme.2010.039248.

Lissauer ME, Naranjo LS, Kirchoffner J, Scalea TM, Johnson SB. Patient characteristics associated with end-of-life decision making in critically ill surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:766–70. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.003.

Hoel H, Skjaker SA, Haagensen R, Stavem K. Decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment in a Norwegian intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58:329–36. doi:10.1111/aas.12246.

van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet. 2003;362:345–50. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14019-6.

Bosshard G, Zellweger U, Bopp M, Schmid M, Hurst SA, Puhan MA, Faisst K. Medical End-of-life practices in Switzerland. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:555. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7676.

Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, de Jong-Krul GJ, van Delden JJ, van der Heide A. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 – 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;380:908–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61034-4.

Teixeira C, Ribeiro O, Fonseca AM, Carvalho AS. Burnout in intensive care units - a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: a descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13:38. doi:10.1186/1471-2253-13-38.

Ptacek JT, Fries EA, Eberhardt TL, Ptacek JJ. Breaking bad news to patients: physicians’ perceptions of the process. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:113–20.

Magelssen M, Kaushal S, Nyembwe KA. Intending, hastening and causing death in non-treatment decisions: a physician interview study. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(9):592-6. doi:10.1136/medethics-2015-103022.

Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, Bader AM, Barnato AE, Gawande AA, Jha AK. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1408–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3.

Kelley AS. Treatment intensity at end of life—time to act on the evidence. Lancet. 2011;378:1364–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61420-7.

Emanuel EJ, Young-Xu Y, Levinsky NG, Gazelle G, Saynina O, Ash AS. Chemotherapy use among medicare beneficiaries at the End of life. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:639–43. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00011.

Buiting HM, Rurup ML, Wijsbek H, van Zuylen L, den Hartogh G. Understanding provision of chemotherapy to patients with end stage cancer: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1933. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1933.

Seale C. The role of doctors’ religious faith and ethnicity in taking ethically controversial decisions during end-of-life care. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:677–82. doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036194.

Schildmann J, Baumann A, Cakar M, Salloch S, Vollmann J. Decisions about limiting treatment in cancer patients: a systematic review and clinical ethical analysis of reported variables. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:884–92. doi:10.1089/jpm.2014.0441.

Schildmann J, Tan J, Salloch S, Vollmann J. “Well, I think there is great variation…”: a qualitative study of oncologists’ experiences and views regarding medical criteria and other factors relevant to treatment decisions in advanced cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18:90–6. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0206.

Bosshard G, Fischer S, van der Heide A, Miccinesi G, Faisst K. Intentionally hastening death by withholding or withdrawing treatment. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:322–6. doi:10.1007/s00508-006-0583-4.

Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Malin JL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4387–95. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055.

Maitra RT, Harfst A, Bjerre LM, Kochen MM, Becker A. Do German general practitioners support euthanasia? results of a nation-wide questionnaire survey. Eur J Gen Pract. 2005;11:94–100.

Schildmann J, Hoetzel J, Mueller-Busch C, Vollmann J. End-of-life practices in palliative care: a cross sectional survey of physician members of the German society for palliative medicine. Palliat Med. 2010;24:820–7. doi:10.1177/0269216310381663.

Winkler EC, Reiter-Theil S, Lange-Riess D, Schmahl-Menges N, Hiddemann W. Patient involvement in decisions to limit treatment: the crucial role of agreement between physician and patient. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2225–30. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9515.

Riessen R, Bantlin C, Wiesing U, Haap M. Therapiezieländerungen auf einer internistischen intensivstation. Einfluss von willensäußerungen der patienten auf therapieentscheidungen. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2013;108:412–8. doi:10.1007/s00063-013-0233-3.

Dornberg M. Angefragt: sterbehilfe. In: Behandlungsbegrenzung und sterbehilfe aus der sicht internistischer krankenhausärzte: ergebnisse einer befragung und medizinethischer bewertung. Frankfurt: Peter Lang; 1997.

Wehkamp KH. Sterben und Töten. In: Euthanasie aus sicht deutscher ärztinnen und ärzte: ergebnisse einer empirischen studie. Dortmund: Humanitas Verlag; 1998.

Putz W. Legal basics in palliative care. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2016;141:389–93. doi:10.1055/s-0041-108083.

Miccinesi G, Fischer S, Paci E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Cartwright C, van der Heide A, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards end-of-life decisions: a comparison between seven countries. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1961–74. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.061.

Bosshard G, Nilstun T, Bilsen J, Norup M, Miccinesi G, van Delden JJM, et al. Forgoing treatment at the End of life in six european countries. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:401–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.4.401.

Schildmann J, Dahmen B, Vollmann J. Ärztliche handlungspraxis am lebensende. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:e1–6. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1387410.

Seale C. Characteristics of end-of-life decisions: survey of UK medical practitioners. Palliat Med. 2006;20:653–9. doi:10.1177/0269216306070764.

Lofmark R, Nilstun T, Cartwright C, Fischer S, van der Heide A, Mortier F, et al. Physicians’ experiences with end-of-life decision-making: survey in six European countries and Australia. BMC Med. 2008;6:4. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-6-4.

Martins Pereira S, Pasman HR, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Old age and forgoing treatment: a nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Med Ethics. 2015;41:766–70. doi:10.1136/medethics-2014-102367.

Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1174–89. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eacf2.

Smets T, Rietjens JA, Chambaere K, Coene G, Deschepper R, Pasman HR, Deliens L. Sex-based differences in end-of-life decision making in Flanders, Belgium. Med Care. 2012;50:815–20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182551747.

Seale C. Hastening death in end-of-life care: A survey of doctors. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1659–66. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.025.

Seale C. End-of-life decisions in the UK: a response to van der heide and colleagues. Palliat Med. 2009;23:567–8. doi:10.1177/0269216309106500.

van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Deliens L, van Delden J, van der Maas P. End-of-life decisions in the United Kingdom. Palliat Med. 2009;23:565–6. doi:10.1177/0269216309106457.

Mori M, Shimizu C, Ogawa A, Okusaka T, Yoshida S, Morita T. A national survey to systematically identify factors associated with Oncologists’ attitudes toward End-of-life discussions: what determines timing of End-of-life discussions? Oncologist. 2015;20:1304–11. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0147.

Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers Jr SO, Baum SK, Virnig BA, Huskamp HA, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006. doi:10.1002/cncr.24761.

Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi:10.1136/bmj.c1345.

Hammes BJ, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD. A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability, and specificity of advance care plans in a county that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1249–55. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02956.x.

Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, Rowland JH, Ballman KV, Cohen HJ, et al. Designing therapeutic clinical trials for older and frail adults with cancer: U13 conference recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2587–94. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0418.

Schildmann J, Vollmann J. Behandlungsentscheidungen bei patienten mit fortgeschrittenen tumorerkrankungen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2010;135:2230–4. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1267505.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all physicians participating in this study, the German state chambers of physicians of Westphalia-Lippe, North Rhine, Saarland, Saxony and Thuringia supporting this study and the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-University Bochum.

Funding

We were supported by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-University Bochum in covering the publication costs.

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be shared at this stage because further analyses are planned.

Authors’ contributions

BD, JV, SN and JS were involved in the study and manuscript writing and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

Birte Dahmen is a research assistant at the Institute for Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany.

Jochen Vollmann, MD, PhD, is a professor and director of the Institute for Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany.

Stephan Nadolny, MSc, is a researcher at the Institute for Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany.

Jan Schildmann, MD, MA, is Professor for Medical Ethics at the Wilhelm Löhe University of Applied Science, Fürth, and a specialist for internal medicine at the Department of Medicine III, Klinikum der Universität München, Campus Großhadern.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Ruhr-University Bochum approved this research (AZ 4196–11). Consent was taken for granted when physicians returned the questionnaire anonymously.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahmen, B.M., Vollmann, J., Nadolny, S. et al. Limiting treatment and shortening of life: data from a cross-sectional survey in Germany on frequencies, determinants and patients’ involvement. BMC Palliat Care 16, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0176-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0176-6