Abstract

Background

Recently, there has been considerable innovation in artificial intelligence (AI) for healthcare. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) show excellent object detection and classification performance. This study assessed the accuracy of an artificial intelligence (AI) application for the detection of marginal bone loss on periapical radiographs.

Methods

A Faster region-based convolutional neural network (R-CNN) was trained. Overall, 1670 periapical radiographic images were divided into training (n = 1370), validation (n = 150), and test (n = 150) datasets. The system was evaluated in terms of sensitivity, specificity, the mistake diagnostic rate, the omission diagnostic rate, and the positive predictive value. Kappa (κ) statistics were compared between the system and dental clinicians.

Results

Evaluation metrics of AI system is equal to resident dentist. The agreement between the AI system and expert is moderate to substantial (κ = 0.547 and 0.568 for bone loss sites and bone loss implants, respectively) for detecting marginal bone loss around dental implants.

Conclusions

This AI system based on Faster R-CNN analysis of periapical radiographs is a highly promising auxiliary diagnostic tool for peri-implant bone loss detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental implants are important for restoring biological function in patients with missing teeth [1, 2] and have become increasingly popular since the 1980s [3]. Monitoring and maintenance are critical for long-term stability after implantation [4]. Marginal bone resorption is an important parameter that should be monitored. Bone loss of < 1.5 mm at 1-year post-loading is generally considered acceptable, followed by the loss of 0.2 mm annually thereafter [5, 6]. In cases where bone loss exceeds this amount, careful investigation is needed, including in cases showing gradual loss after osseointegration. Bone loss is initiated and maintained by iatrogenic factors or local conditions (e.g. occlusal trauma, implant factors, prosthetic restorations, etc.) [5, 7, 8]. Bone loss can be classified into late and additional types [9]. By monitoring marginal bone resorption, early changes in clinical factors can be identified. When additional bone loss is observed along with peri-implant connective tissue inflammation (i.e. bleeding and/or suppuration), a diagnosis of peri-implantitis is made [10]. This requires treatment and oral health education for the patient.

Bone loss is usually evaluated on radiographs. A difference in measurements between examiners of approximately 1–2 mm is considered to reflect meaningful interexaminer variation [11]. For general practitioners, evaluating marginal bone loss around implants can be difficult. In clinical practice, detection of the peri-implant bone level relies on imaging findings. Commonly used imaging modalities include cone-beam computed tomography, panoramic radiography, and periapical radiography. Cone-beam computed tomography can depict the three-dimensional relationship between a dental implant and the surrounding alveolar bone, and studies have demonstrated robust accuracy of this modality for the detection of peri-implant bone defects [12, 13]. Other studies have sought to identify the bone condition around implants using periapical radiographs [14, 15]. Two-dimensional radiographic images are widely used in clinical practice because of their low cost and radiation dose; thus, bone defects are commonly measured on conventional periapical radiographs. Assessment of the peri-implant marginal bone level on conventional periapical radiographs is generally difficult because the three-dimensional bone shape is represented on a two-dimensional image. Therefore, the boundaries of the bone around the implant, as well as the buccal and lingual bone heights, should be determined by experienced clinicians [16]. Inexperienced clinicians may make diagnostic errors and false diagnoses according to clinical studies on learning curve [17]. Implant restoration is an increasingly popular procedure, but follow-up thereof can involve a considerable amount of clinical time and effort. Furthermore, interpretations of radiographs tend to vary among observers. Automated systems for reading and analysing periapical radiographs of dental implants may help to address these issues.

Recently, there has been considerable innovation in artificial intelligence (AI) for healthcare, which can also aid digital dentistry and telemedicine [18]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) show excellent object detection and classification performance [19]. Many studies based on CNNs have been conducted in the field of dentistry [20, 21], for tooth numbering [22] and analysis of dental caries [23], osteoporosis [24], periodontal bone loss [25], submerged primary teeth [26] and dental implants [27,28,29]. CNNs learn directly from raw input data and classify images without the requirement for manual feature extraction. Region-based convolutional neural networks (R-CNNs) have been developed for object detection tasks, whereby target objects (regions of interest) are automatically identified and annotated [30,31,32,33]. Subsequently, the R-CNN was upgraded to Faster R-CNN, which is more efficient. Based on Faster R-CNN, the Mask R-CNN method was developed; this can detect targets in images and provides high-quality segmentation results [34]. To our knowledge, few studies have used Faster R-CNN for detection of marginal bone loss around dental implants on periapical radiographs [28].

The purpose of this study was to develop an automated system for identifying marginal bone loss around dental implants in periapical radiographs using a deep learning-based object detection method, and then to investigate the accuracy of the system.

Materials and methods

Data collection and annotation

This study was approved by the bioethics committee of Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology (PKUSSIRB-201837103). The study was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines. The data are anonymous, and the requirement for informed consent was therefore waived. In total, 2500 digital periapical radiographs of bone-level implants were collected from Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology. The inclusion criteria were as follows: periapical radiographs of dental implants, appropriate radiation exposure, and radiographs of dental implants acquired in parallel. The exclusion criteria were as follows: excessively bright or dark images precluding distinguishment of marginal bone around dental implants, severely distorted images of dental implants, and/or graft material hindering observation of the alveolar bone [28]. Each digital radiograph was exported with a resolution of 96 dpi and size of approximately 300–500 × 300–400 pixels. Each radiograph was then rotated so that the implant was perpendicular to the horizontal plane and saved in JPG format image file with a unique identification code as a component of the primary dataset. All patient information (e.g. name, sex, and age) was removed from the images according to our previous experimental investigations [20, 22]. An experienced dentist (> 5 years of clinical experience) assessed the images for marginal bone loss around the dental implants. Overall, 835 images with marginal bone loss around the implants were detected and classified into the case group. The control group was then formed from 835 randomly selected radiographs from the primary dataset without marginal bone loss around the implants.

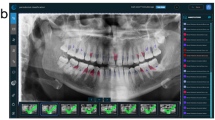

This study used a balanced dataset [26]. Images from the case and control group datasets were randomly assigned to one of three datasets: a training set of 1,370 images, a validation set of 150 images, and a test set of 150 images. The training and validation datasets were used to train a Faster R-CNN [32, 33]. Subsequently, the dentist with more than 5 years of clinical experience (reference standard) drew a rectangular bounding box around the dental implants and crowns, and around areas of marginal bone loss surrounding implants (ground truth bounding box for the case group). Another oral and maxillofacial radiologist confirmed the initial bounding box positions. During annotation, the clinicians drew the smallest possible bounding box around each area of marginal bone loss surrounding the implants in each image (Fig. 1).

“Keypoints” for marginal bone loss assessment. a platform switch implant; b platform match implant. Red points indicate coronal keypoints; green points indicate apical keypoints. For platform-switched implants, the coronal keypoints were located on top of each implant. For bone-level platform-matched implants, the coronal keypoints were located on the bottom of the implant neck. The apical keypoints comprised the first point of contact between the bone and implant. The yellow bounding boxes denote areas of marginal bone loss

For platform-matched implants, the bottom of the implant neck near the most coronal thread was considered as the top of the implant [7]. For platform-switched implants, the most coronal edge was considered as the top of the implant [14]. The apical “keypoints” were the first contact points of the bone and implant. Coordinates in the image were set in accordance with the distance from the top-left corner. The bounding box was described in terms of its top left and bottom right corners (xmin, ymin; xmax, ymax).

Training and validation of the Faster R-CNN

An object detection package [33] for TensorFlow was used for object detection. Inception Resnet v2 (Atrous version), a state-of-the-art object detector, was used as the neural network model. The model was trained using a PC with a Quadro RTX 8000 graphics processing unit (NVIDIA, USA), 48 GB memory and 4608 CUDA cores. The backend algorithms were executed using TensorFlow (version 1.13.1) running on the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system.

A set of 1370 annotated X-ray images were used to train the Faster R-CNN for object recognition. There were 60,000 iterations and an initial learning rate of 0.0003, which was reduced to 0.00006 after 30,000 iterations.

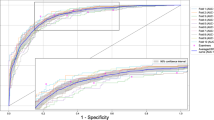

To rapidly determine model performance, the average precision [35] (AP; i.e., the area under the curve) of the implant and marginal bone loss lesion areas, as well as the mean average precision (mAP) of an intersection over unit (IoU) of > 0.5, were calculated using the following equation:

where Areapred and Areagt represent the predicted area of the bounding box and the ground truth bounding box, respectively. The IoU threshold was set at 0.5 because this value is commonly used in studies of object detection [36]. The mAP was calculated by determining the mean AP across all classes. Higher values indicated better learning system performance.

Diagnostic performance analysis

The diagnostic accuracy of the model was determined by comparison with assessments performed by dentists. In total, 150 radiographic images were analysed by three dentists: a resident dentist (Dr1), an MD student with 2 years of experience (Dr2), and an experienced dentist (5 years of clinical experience; reference standard). Observers (Dr1 and Dr2) were asked to indicate areas of pathology and potential bone loss around implants on the images. The classification and detection performance of the AI system and observers was evaluated by comparison with the reference standard.

A confusion matrix (Table 1) summarising the predicted and actual results was used to determine the accuracy of the model. The sensitivity, specificity, mistake diagnostic rate, omission rate, and positive predictive value were calculated as follows:

Interobserver agreement with respect to the presence/absence of marginal bone loss around implants was calculated using the kappa (κ) statistic in SPSS software (24; SPSS Inc., USA). The κ values were classified as follows: 0, poor; 0.00–0.20, weak; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial; and 0.81–1.00, almost perfect agreement [37].

Statistical analysis

The training and test datasets were used to create optimal weights for a deep CNN model. A confusion matrix was used to calculate the accuracy of the model, as stated above. The sensitivity, specificity, mistake diagnostic rate, omission diagnostic rate, and positive predictive value of the deep CNN model were calculated based on its performance with the test dataset, using a TensorFlow framework and Python. Interobserver agreement regarding the presence of marginal bone loss was given by the κ statistic, calculated in SPSS as also stated above.

Results

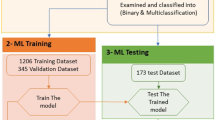

The AP for implants approached 0.99 after 10,000 iterations (Fig. 2a), indicating that the implants could be detected with high accuracy. The AP for marginal bone loss gradually increased with an increasing number of iterations. When the number of iterations reached 30,000, the AP value fluctuated slightly; it eventually stabilised at 0.47 after 60,000 iterations (Fig. 2b). The mAP of implants and marginal bone loss was 0.73 (Fig. 2c).

The average precision [35] (AP; i.e., the area under the curve) of the implant and marginal bone loss lesion areas, as well as the mean average precision (mAP) of an intersection over unit (IoU) of > 0.5, were calculated. a average precision of implant classification; b average precision of marginal bone loss lesion classification; c mean average precision

Table 2 provides information on the implants in the training and test datasets. As shown in Fig. 3, although some diagnoses were missed, the bone loss area detected by Faster R-CNN was generally similar to the ground truth bounding box. With increasing severity of bone loss, the Faster R-CNN model and observer annotations converged.

Marginal bone resorption was assessed on the basis of single implants, as well as their mesial and distal sites. Table 3 compares the performance of the AI system and observers. For bone loss around implants and lesion sites, the deep CNN had positive predictive values of 81% and 87%, sensitivities of 67% and 75%, and specificities of 87% and 83%, respectively. The values for these parameters showed considerable variation between the observers.

Notably, there was fair interobserver agreement (κ = 0.399 and 0.383 for bone loss sites and implants, respectively) between the MD student and expert dentist. However, the agreement between the AI system and expert was moderate to substantial (κ = 0.547 and 0.568 for bone loss sites and implants, respectively). Finally, there was moderate agreement (κ = 0.555 and 0.544 for bone loss sites and implants, respectively) between the resident dentist and expert dentist (Table 4).

Discussion

AI technologies can be clinically evaluated in terms of diagnostic performance, patient outcomes, and the cost–benefit ratio [38, 39]. For many years, machine predictions were inferior to those of humans in terms of object detection and instance segmentation, and extensive comparisons of AI and human observers are lacking. In this study, implants were detected with high accuracy by the AI system. Marginal bone loss detection is often challenging, so several metrics of diagnostic performance were used for model evaluation in this study. Specificity represents the probability that a marginal bone loss bounding box actually contains the lesion area, while sensitivity represents the probability that an image is correctly labelled as “disease”. The κ statistic test is useful for evaluating consistency between a new diagnostic method and the gold standard; it can also be used to evaluate consistency between two clinicians in terms of their diagnostic assessments of specific patients. The above-described metrics allow for model evaluation and comparison among clinicians. The CNN model used in this study performed similarly to the resident dentist, but less well than the experienced dentist; however, overall we conclude that the CNN model may facilitate the detection of marginal bone loss around implants.

The impact of implant-supported prosthesis type on peri-implant bone loss and peri-implantitis remains unclear [7, 40]. The differential effects on loss of marginal bone between platform-matched and -switched implants has received increasing attention in recent years; a meta-analysis by Chrcanovic et al. [41] suggested that significantly less marginal bone loss occurs with the latter type of implant. Dentists must distinguish the abutment-implant connection type and appropriate reference points when analysing radiographs for marginal bone loss around dental implants. Platform-switched level implants should maintain marginal bone stability at a level equivalent to the top of the implant [14]. Platform-matched implants have a smooth neck, and the marginal bone should be stabilised at the junction between the smooth and rough implant surfaces [42]. In this study, we divided the marginal bone loss training data according to the implant-abutment connection type, and the bone resorption areas automatically identified by the CNN were generally consistent with these classifications (Fig. 3). These findings differed from those of Cha et al. [28], whose dataset included various implants with different implant-abutment junctions. In that study, the most coronal thread of the implant was used as a threshold position.

According to the VIII European Workshop on Periodontology [43], radiographs of implants are recommended after physiological remodelling (generally at the time of prosthesis fitting) to assess changes in the level of crestal bone. These baseline radiographs were unavailable for some patients in our dataset. Exposure of the rough implant surface can serve as an indicator of bone resorption around the implant. In this study, bounding boxes were used for qualitative detection of marginal bone loss (Fig. 2). The Faster R-CNN model was used in this study for feature detection and classification, while Cha et al. [28] used a Mask R-CNN model that detects and classifies targets by drawing target frames, and then segments targets at the pixel level. However, the cost of training is considerable because a set of keypoints must be precisely annotated for model training; also, specialised equipment is needed for training [34].

Although AI is a rapidly developing technology, our research nevertheless provides important baseline data for future studies. However, this study had some limitations. Firstly, for assessment of the real-world clinical performance of high-dimensional AI algorithms that analyse medical images using deep learning, external validation studies are needed [44,45,46]. This study used a balanced database, but the incidence of bone resorption at implant margins was low. Second, because subtle changes in marginal bone morphology are difficult to evaluate, standardised radiographs produced via the paralleling technique have important roles in monitoring marginal bone levels around endosseous implants [42]. Model performance may be improved by the parallel projection method.

Conclusions

The Faster R-CNN model used in this study performed similarly to the resident dentist, but less well than the experienced dentist; overall we conclude that our Faster R-CNN could detect peri-implant bone loss on periapical radiographs and may facilitate the development of accurate diagnostic tools. In the future, model performance may be improved by more high qualified training images.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Boven GC, Raghoebar GM, Vissink A, et al. Improving masticatory performance, bite force, nutritional state and patient’s satisfaction with implant overdentures: a systematic review of the literature. J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42:220–33.

Yukumi K, Korenori A, Toshiki K, et al. Oral health-related quality of life in patients with implant treatment. J Adv Prosthodont. 2017;9:476–81.

Shulman LB, Driskell TD. Dental implants: a historical perspective. In: Block M, Kent J, Guerra L, editors. Implants in dentistry. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders; 1997.

Lang NP, Berglundh T. Periimplant diseases: where are we now?—consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl. 11):178–81.

Albrektsson T, Buser D, Chen ST, et al. Statements from the Estepona Consensus meeting on peri-implantitis. Clin Implant Dent R. 2012;14:781–2.

Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, et al. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1986;1:11.

Dalago HR, Schuldt Filho G, Rodrigues MA, et al. Risk indicators for Peri-implantitis. Across-sectional study with 916 implants. Clin Oral Implan Res.2017;28:144–150.

Albrektsson T, Canullo L, Cochran D, et al. "Peri-Implantitis": a complication of a foreign body or a man-made "Disease". Facts and Fiction. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2016;18:840–849

de Souza JG, Neto AR, Filho GS, et al. Impact of local and systemic factors on additional peri-implant bone loss. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:415–24.

Insua A, Monje A, Wang HL, et al. Patient-centered perspectives and understanding of peri-implantitis. J Periodontol. 2017;88:1153–62.

Serino G, Sato H, Holmes P, et al. Intra-surgical vs. radiographic bone level assessments in measuring peri-implant bone loss. Clin Oral Implants Res.2017;28:1396–1400.

Ritter L, Elger MC, Rothamel D, et al. Accuracy of peri-implant bone evaluation using cone beam CT, digital intra-oral radiographs and histology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2014;43:20130088.

Al-Okshi A, Paulsson L, Ebrahim E, et al. Measurability and reliability of assessments of root length and marginal bone level in cone beam CT and intraoral radiography: a study of adolescents. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2019;48:20180368.

El Hage M, Nurdin N, Abi Najm S, et al. Osteotome sinus floor elevation without grafting: a 10-year study of cone beam computerized tomography vs periapical radiography. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2019;39:e89–97.

Hermann JS, Cochran DL, Nummikoski PV, et al. Crestal bone changes around titanium implants. A radiographic evaluation of unloaded nonsubmerged and submerged implants in the canine mandible. J Periodontol.1997, 68: 1117–1130.

Misch CE. Chapter 3—an implant is not a tooth: a comparison of periodontal indices. In: Misch CE(ed). Dental implant prosthetics. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2015.p.46–65

Cassetta M, Altieri F, Giansanti M, et al. Is there a learning curve in static computer-assisted implant surgery? A prospective clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49:1335–42.

Gherlone E, Polizzi E, Tetè G, et al. Dentistry and Covid-19 pandemic: operative indications post-lockdown. New Microbiol. 2021;44:1–11.

Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60:84–90.

Chen H, Li H, Zhao Y, et al. Dental disease detection on periapical radiographs based on deep convolutional neural networks. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2021;16:649–61.

Khanagar SB, Al-Ehaideb A, Maganur PC, et al. Developments, application, and performance of artificial intelligence in dentistry—a systematic review. J Dent Sci. 2021;16:508–22.

Chen H, Zhang K, Lyu P, et al. A deep learning approach to automatic teeth detection and numbering based on object detection in dental periapical films. Sci Rep. 2019;9:3840.

Casalegno F, Newton T, Daher R, et al. Caries detection with near-infrared transillumination using deep learning. J Dent Res. 2019;98:1227–33.

Smets J, Shevroja E, Hügle T, et al. Machine learning solutions for osteoporosis—a review 2021. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36:833–51.

Chang HJ, Lee SJ, Yong TH, et al. Deep learning hybrid method to automatically diagnose periodontal bone loss and stage periodontitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7531.

Caliskan S, Tuloglu N, Celik O, et al. A pilot study of a deep learning approach to submerged primary tooth classification and detection. Int J Comput Dent. 2021;24:1–9.

Lerner H, Mouhyi J, Admakin O, et al. Artificial intelligence in fixed implant prosthodontics: a retrospective study of 106 implant-supported monolithic zirconia crowns inserted in the posterior jaws of 90 patients. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:80.

Cha JY, Yoon HI, Yeo IS, et al. Peri-implant bone loss measurement using a region-based convolutional neural network on dental periapical radiographs. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1009.

Sukegawa S, Yoshii K, Hara T, et al. Deep neural networks for dental implant system classification. Biomolecules. 2020;10:984.

Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, et al. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In 2014 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2014;35:580–587.

Ren S, He K, Girshick R, et al. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE T Pattern Anal. 2017;39(6):1137–49.

Laishram A, Thongam K. Detection and classification of dental pathologies using faster-RCNN in orthopantomogram radiography image. In: 2020 7th international conference on signal processing and integrated networks (SPIN), pp. 423–428.

Huang J, Rathod V, Sun C, et al. Speed/accuracy trade-offs for modern convolutional object detectors. In: 2017 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 2017;3296–3297.

He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, et al. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal. 2020;42:386–97.

Everingham M, Gool LV, Williams C, et al. Visual object classes (VOC) challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2009;88(2):303–38.

Zhao ZQ, Zheng P, Xu ST, et al. Object detection with deep learning: a review. IEEE Trans Neur Net Lear. 2019:30:3212–3232.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Park SH, Kressel HY. Connecting technological innovation in artificial intelligence to real-world medical practice through rigorous clinical validation: what peer-reviewed medical journals could do. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e152.

Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Med Decis Mak. 1991;11:88–94.

Canullo L, Pesce P, Patini R, et al. What are the effects of different abutment morphologies on peri-implant hard and soft tissue behavior? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Prosthodont. 2020;33:297.

Chrcanovic BR, Albrektsson T, Wennerberg A. Platform switch and dental implants: a meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015;43:629–46.

Afrashtehfar KI, Brägger U, Hicklin SP. Reliability of interproximal bone height measurements in bone- and tissue-level implants: a methodological study for improved calibration purposes. Int J Max Impl. 2020;35:289–96.

Sanz M, Chapple IL. Working Group 4 of the VIII European Workshop on Periodontology. Clinical research on peri-implant diseases: consensus report of Working Group 4. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39 Suppl 12:202–206.

Park SH, Han K. Methodologic guide for evaluating clinical performance and effect of artificial intelligence technology for medical diagnosis and prediction. Radiology. 2018;286:800–9.

England JR, Cheng PM. Artificial intelligence for medical image analysis: a guide for authors and reviewers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212:513–9.

Park SH. Diagnostic case-control versus diagnostic cohort studies for clinical validation of artificial intelligence algorithm performance. Radiology. 2019;290:272–3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the residents (Dr Feilong Wang, Dr Xiao Zhao, and Dr Fanyu Liao) who helped prepare the dataset for this study

Funding

This study was financially supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51705006); National Program for Multidisciplinary Cooperative Treatment on Major Diseases, Grant Number: PKUSSNMP-202004 and PKUSSNMP-201901.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceptualized by YSL, HC and ML. The project implementation was led by HC, ML and SMW. LM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YSL and HC read and contributed to several versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the bioethics committee of Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology (PKUSSIRB-201837103). The data are anonymous, and the requirement for informed consent was therefore waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in relation to the present study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Wang, S., Chen, H. et al. A pilot study of a deep learning approach to detect marginal bone loss around implants. BMC Oral Health 22, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-02035-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-02035-8