Abstract

Background

Marital status proves to be an independent prognostic factor in a variety of cancers. However, its prognostic impact on gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms (G-NEN) has not been investigated.

Methods

We identified 3947 G-NEN patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Meanwhile, propensity scores for marital status were used to match 506 unmarried patients with 506 married patients. We used Kaplan–Meier method and multivariate Cox regression to analyse the association between marital status and the overall survival (OS) and G-NEN cause-specific survival (CSS) before matching and after matching.

Results

Married patients enjoyed better OS and CSS, compared with divorced/separated, single, and widowed patients. Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that unmarried status was associated with higher mortality hazards for both OS and CSS among G-NEN patients. Additionally, widowed individuals had the highest risks of overall (adjusted hazard ratio (HR): 1.56, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.35–1.81, P < 0.001) and cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.05–1.68, P = 0.02) compared to other unmarried groups in both males and females. Furthermore, unmarried status remained an independent prognostic and risk factor for both OS (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.19–1.90, P = 0.001) and CSS (HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.10–2.05, P = 0.01) in 1:1 propensity score-matched analysis.

Conclusion

Marital status was an independent prognostic factor for G-NEN. Meanwhile, widowed patients with G-NEN had the highest risk of death compared with single, married, and divorced/separated patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms (G-NENs) comprise a heterogeneous collective of tumours arising from the enterochromaffin-like cell, and account for approximately 7% of all neuroendocrine neoplasms [1]. In the past few decades, statisticians have witnessed a tenfold rise in the incidence of G-NEN, possibly due to progressed endoscopic screening skills and increased pathologic experience [2, 3]. G-NEN can be subdivided into three subtypes: type I associated with autoimmune atrophic gastritis, type II associated with Zolinger-Ellison syndrome/gastrinoma, and type III occurring sporadic without hypergastrinemia [4].

Nowadays, many clinicians and nurses mainly focused on clinicopathological characteristics, without taking the impact of psychological and social factors into consideration. In reality, these sociopsychological factors do have an influence on patient outcomes [5]. Marriage is one of the most important source of social support, which affects physical health through integrative physiological mechanisms [6]. Previous studies have pointed out that married patients tend to have better survival outcome in several cancer types [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, whether marriage has a “protective” effect for G-NEN patients has not yet been established. In the present study, we examined the data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry database to assess the effects of marital status on outcomes of patients with G-NEN.

Methods

Data sources and study population

The analysis was performed based on data obtained from the SEER registry. Using the National Cancer Institute’s SEER∗Stat software (Version 8.3.5), we identified G-NEN patients diagnosed from 1973 to 2015 with a known marital status. Primary site codes C16.0 to C16.9 and histological type codes were 8153/3: Gastrinoma, malignant, 8240/3: Carcinoid tumour, NOS, 8241/3: Enterochromaffin cell carcinoid, 8242/3: Enterochromaffin-like cell tumour, malignant, 8246/3: Neuroendocrine carcinoma, NOS, and 8249/3: Atypical carcinoid tumour, according to International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3). The diagnosis of G-NENs was based on CS Schema v0204+ which classification as NETstomach. However, because of the data source and the study design, the classification into three clinical subtypes of G-NEN according to international guidelines [16] was not feasible in this study. Patients with nonprimary G-NET were excluded. The cause of death and survival of all patients were clearly known.

We have got permission to access the research data in SEER database and the reference number was 14,827-Nov2017. Since this was a retrospective cohort study, no ethical approval was required for analyses of these non-identifiable data.

Statistical analysis

The clinical characteristics of the patients with G-NEN were presented with descriptive statistics. The categorical variable was presented with number (%). Chi-square tests were used to examine the association between marital status and other variables. Overall survival (OS), and cause-specific survival (CSS) rates were examined using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank tests.

Propensity scores (PSs) were estimated via a multivariable logistic regression model to balance 2 groups (married/unmarried) with respect to age at diagnosis, sex, year of diagnosis, ethnicity, tumour grade, and tumour stage. We then matched married and unmarried patients who had very similar PSs. 1:1 PS-matching was conducted using the nearest-neighbour algorithm with a caliper width of 0.01. Upon obtaining satisfactory subjects’ characteristics between married/unmarried groups, the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of marital status over OS and CSS was estimated via a Cox proportional hazards regression model in all subjects and PS-matched cohort. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were also plotted.

All statistical tests were 2-sided, and a value of P less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS version 22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and R (version 3.4.3; R Development Core Team, http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 3947 patients with G-NEN who satisfied the inclusion criteria, comprising 2377 (60.2%) married patients and 1570 (39.8%) unmarried subjects, were identified in the SEER database. Of the unmarried subjects, 408 (10.3%) were divorced or separated, 646 (16.4%) were single, and 516 (13.1%) were widowed. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of these patients were described in Table 1, stratified by marital statuses. Chi-square tests showed significant differences in most variables, including age at diagnosis (P < 0.001), sex (P < 0.001), year at diagnosis (P < 0.001), ethnicity (P < 0.001), tumour size (P = 0.02), and surgery performed (P < 0.001).

The effects of marital status on overall and cause-specific survival

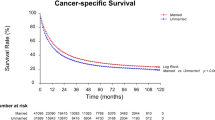

We applied Kaplan-Meier curves to evaluate the OS rates of G-NEN patients. As shown in Fig. 1a, unmarried status was associated with worse prognosis compared to married status according to the Cox regression model (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33–1.64, P < 0.001). After adjusting baseline parameters, including age, sex, year at diagnosis, race, tumour grade, tumour size, and surgery performed, unmarried patients still had poorer prognosis than married counterparts (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.33–1.67, P < 0.001). The CSS rates of G-NEN patients were also displayed by plotting Kaplan-Meier curves. As shown in Fig. 1b, unmarried status contributed to unfavourable prognosis (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.10–1.51, P = 0.002) according to the Cox model and even after adjusting confounding factors (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09–1.54, P = 0.003).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of G-NEN patients according to marital status. a. overall survival between married and unmarried patients; b G-NEN cause specific survival between married and unmarried patients; c. overall survival among single, married, widowed, and divorced/seperated patients; d overall survival of male patients; e. overall survival of female patients

To explore whether different unmarried status led to worse prognosis than married status, we divided unmarried subjects into three subgroups: the divorced/separated, single and widowed. On univariable analysis, windowed patients had a statistically significant higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR 3.35, 95% CI 2.05–2.68, P < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 1c, compared with married patients, windows had significantly lower OS rate. On multivariable analysis, unmarried status (including single marital status) remained an independent prognostic factor for increased risk of all-cause mortality, while single status did not indicate higher risk of cancer-specific death compared to married G-NEN patients.

In addition, age, sex, tumour grade, tumour stage, and surgery performed were validated as independent prognosis factors for OS and CSS in the multivariate Cox analyses. The detailed description of each prognostic factor is displayed in Table 2. We also explored the association between marital status and survival only in patients well-differentiated tumours. As displayed in Table 3, both single (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.03–2.32, P = 0.03) and widowed (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.78, P = 0.004) patients were associated with decreased survival time, compared with married counterparts (P for trend = 0.02), after adjusting for known confounders.

Subgroup analysis of the effect of marital status stratified by gender

Since widowed patients had the poorest OS, we analysed whether unmarried status, especially widowed status contributed to the poor survival rates in the subgroups of G-NEN patients stratified by gender. As shown in Table 4, marital status was found to be an independent prognostic factor of OS in both male and female G-NEN patients according to the log-rank tests and Cox regression analysis (Fig. 1d, e). Particularly, widowhood affected the prognosis more in women than in men.

Clinical outcomes after propensity score matching

To further confirm the findings that married G-NEN patients survived longer and to minimize bias in the previous analysis, we conducted a PS-matching analysis. Using a 1:1 PS-matching method, we matched 506 unmarried patients with 506 married patients. As shown in Table 5, all the baseline variables were clearly well matched (all P > 0.05).

Although the HR was not higher after matching the data than before, unmarried patients still shown poorer OS (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.19–1.90, P = 0.001) and CSS (HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.10–2.05, P = 0.01) in univariate Cox model. In multivariate analysis (Fig. 2), unmarried status was still linked with significantly worse OS (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.09–1.78, P = 0.008). As shown in Fig. 3a and b, survival curves for OS and CSS indicated that married patients showed significantly better survival than their unmarried counterparts. Compared with married patients, widowed patients had a significant reduction in both OS and CSS rate (Fig. 3c, d).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of G-NEN patients according to marital status after propensity score matching. a. overall survival between married and unmarried patients; b G-NEN cause specific survival between married and unmarried patients; c. overall survival among single, married, widowed, and divorced/seperated patients; d G-NEN cause specific survival among single, married, widowed, and divorced/seperated patients

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the impact of marital status at diagnosis on survival outcomes in a SEER cohort of G-NEN patients. Based on relatively large sample size and PS-matched dataset, our study provided results with high validity and reliability. Being married was indicated to exert a protective effect on survival compared to any unmarried status.

The diagnosis of cancer exposes an individual to chronic psychosocial stress, which triggers fight-or-flight responses by activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. From a physiology perspective, psychological stress increases epinephrine, prostaglandins, and glucocorticoid levels, and reduces NK cells and cytotoxic T cells activity [17,18,19]. Then stress induces immune suppression, contributing to tumour proliferation, progression, and metastasis [20, 21]. A cell line study of ovarian cancer demonstrated that stress hormones can also enhance the capacity of tumour cells to invade the extracellular matrix, contributing to tumour metastasis [22]. The detailed mechanism for protective role of marriage on neuroendocrine tumours might be explored in further experimental studies. Typically, oncological patients deny, feel angry, bargain, experience depression, and then gradually accept the reality. Social support, or supportive social network, is greatly needed throughout this process. With emotional support of their spouse, married patients experience less stress and despair [23]. Additionally, patients with less psychosocial stress have better compliance to medical recommendations [24]. Spousal encouragement may increase G-NEN patients’ willingness to survive, and they are more likely to receive treatments like surgery and/or chemotherapy.

With the transformation from biomedical model to biopsychosocial model of illness [25], the importance of sociopsychological factors on oncological diseases has gained increasing attention. Positive psychosocial factors can alleviate the pain and worries of cancer patients, thus improving the treatment compliance, treatment effect, quality of life and survival rate. Therefore, it is of great significance to fully understand the relationship between prognosis of tumour patients and psychosocial factors and to monitor the psychological changes of tumour patients. Sociopsychological factors, including marital status, can impact tumour development and survival of oncological diseases through the regulation of endocrine and immune systems. Our results show that all unmarried groups showed poorer survival outcome compared with the married group, but windowed G-NEN patients have the poorest prognosis, which is also demonstrated in studies regarding gastrointestinal stromal tumour, gastric cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and rectal cancer [26,27,28,29]. Single and separated G-NEN patients tend to be more prepared to build social support networks other than marriage compared to widowed patients. As such, clinicians, nurses, and health care workers need to pay more attention to widowed patients’ emotional need, communicate more with the widowed, and provide them with necessary social support in clinical practice.

Despite of the strengths of this study including large sample size, subgroup analysis, and PS-matching method, there were some potential limitations. First, we ignored effect of the quality of marital life among G-NEN patients in the analysis. This may cause bias since unsatisfactory marriage can result in immune dysregulation [30]. Previous study revealed that marital relationship may change after cancer diagnosis [31]. The SEER database did not provide information on change of marital status after G-NEN diagnosis. Another notable drawback was the inability to classify patients according with the clinical subgroups (Type I, II, III) according with international guidelines [16], where type III tumour showed markedly worse outcome than others. Since type I and II of G-NENs comprise vast majority of well-differentiated tumours in general, and most type III tumour can be classified into poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, we tried to compensate for this limitation by validating the prognostic effect of marital status in well-differentiated tumours only. Besides, we failed to adjust some recognized prognostic parameters such as chemotherapy and radiation in the regression model due to lack of detailed information in the database.

In addition to marital status, many other socioeconomic factors (e.g. household income and medical insurance status) and sociopsychological factors may also play a role in G-NEN patients’ outcomes, which warrant further investigation. Moreover, further in-depth investigations according with different G-NEN types are needed to better understand the meaning of the findings in the present study.

Conclusions

In summary, our study found that marital status was an independent prognostic factor among G-NEN patients, and married individuals enjoyed significant survival benefits than those unmarried. Particularly, widowed G-NEN patients suffer the highest mortality risk. It is necessary to provide timely psychological intervention and social support for unmarried, especially widowed G-NEN patients in clinical practice. However, our results should be interpreted with caution since the inability to classify patients into the three clinical types of G-NEN in this study.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the SEER database (seer.cancer.gov).

Abbreviations

- G-NEN:

-

Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- ICD-O-3:

-

International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- CSS:

-

Cause-specific survival

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

O’Connor JM, Marmissolle F, Bestani C, Pesce V, Belli S, Dominichini E, et al. Observational study of patients with gastroenteropancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors in Argentina: results from the large database of a multidisciplinary group clinical multicenter study. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2(5):673–84.

Cao L, Lu J, Lin J, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, et al. Incidence and survival trends for gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms: an analysis of 3523 patients in the SEER database. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(10):1628–33.

Scherubl H, Cadiot G, Jensen RT, Rosch T, Stolzel U, Kloppel G. Neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach (gastric carcinoids) are on the rise: small tumors, small problems? Endoscopy. 2010;42(8):664–71.

Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, Capella C, Solcia E. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(4):994–1006.

Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Dhabhar FS, Sephton SE, McDonald PG, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):240–8.

Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–87.

Alvi MA, Wahood W, Huang AE, Kerezoudis P, Lachance DH, Bydon M. Beyond science: effect of marital status and socioeconomic index on outcomes of spinal cord tumors: analysis from a National Cancer Registry. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:e333–43.

Gao Z, Ren F, Song H, Wang Y, Wang Y, Gao Z, et al. Marital status and survival of patients with chondrosarcoma: a population-based analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:6638–48.

Liang Y, Chen J, Yu Q, Ji T, Zhang B, Xu J, et al. Phosphorylated ERK is a potential prognostic biomarker for Sorafenib response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2017;6(12):2787–95.

Mao Y, Fu Z, Zhang Y, Dong L, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, et al. A seven-lncRNA signature predicts overall survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8823.

Niu Q, Lu Y, Wu Y, Xu S, Shi Q, Huang T, et al. The effect of marital status on the survival of patients with bladder urothelial carcinoma: a SEER database analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(29):e11378.

Pham T, Talukder A, Walsh N, Lawson A, Jones A, Bishop J, et al. Clinical and epidemiological factors associated with suicide in colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;27(2):617.

Xie J, Yang S, Liu X, Zhao Y. Effect of marital status on survival in glioblastoma multiforme by demographics, education, economic factors, and insurance status. Cancer Med. 2018;7(8):3722–42.

Zhang QW, Lin XL, Zhang CH, Tang CY, Zhang XT, Teng LM, et al. The influence of marital status on the survival of patients with esophageal cancer: a population-based, propensity-matched study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):62261–73.

Zhang SL, Wang WR, Liu ZJ, Wang ZM. Marital status and survival in patients with soft tissue sarcoma: a population-based, propensity-matched study. Cancer Med. 2019;8(2):465–79.

Delle Fave G, Kwekkeboom DJ, Van Cutsem E, Rindi G, Kos-Kudla B, Knigge U, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the management of patients with gastroduodenal neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(2):74–87.

Yakar I, Melamed R, Shakhar G, Shakhar K, Rosenne E, Abudarham N, et al. Prostaglandin e (2) suppresses NK activity in vivo and promotes postoperative tumor metastasis in rats. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(4):469–79.

Inbar S, Neeman E, Avraham R, Benish M, Rosenne E, Ben-Eliyahu S. Do stress responses promote leukemia progression? An animal study suggesting a role for epinephrine and prostaglandin-E2 through reduced NK activity. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19246.

Shakhar G, Blumenfeld B. Glucocorticoid involvement in suppression of NK activity following surgery in rats. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;138(1–2):83–91.

Melamed R, Rosenne E, Shakhar K, Schwartz Y, Abudarham N, Ben-Eliyahu S. Marginating pulmonary-NK activity and resistance to experimental tumor metastasis: suppression by surgery and the prophylactic use of a beta-adrenergic antagonist and a prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(2):114–26.

Ben-Eliyahu S, Page GG, Schleifer SJ. Stress, NK cells, and cancer: still a promissory note. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(7):881–7.

Sood AK, Bhatty R, Kamat AA, Landen CN, Han L, Thaker PH, et al. Stress hormone-mediated invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(2):369–75.

Kristofferzon ML, Lofmark R, Carlsson M. Myocardial infarction: gender differences in coping and social support. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(4):360–74.

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–7.

Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–36.

Chen M, Wang X, Wei R, Wang Z. The influence of marital status on the survival of patients with operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a SEER-based study. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2018;34(1):e447.

Wu SG, Zhang QH, Zhang WW, Sun JY, Lin Q, He ZY. The effect of marital status on nasopharyngeal carcinoma survival: a surveillance, epidemiology and end results study. J Cancer. 2018;9(10):1870–6.

Wang X, Cao W, Zheng C, Hu W, Liu C. Marital status and survival in patients with rectal cancer: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) database. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;54:119–24.

Jin JJ, Wang W, Dai FX, Long ZW, Cai H, Liu XW, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):1821–9.

Jaremka LM, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Marital distress prospectively predicts poorer cellular immune function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(11):2713–9.

Harju E, Rantanen A, Helminen M, Kaunonen M, Isotalo T, Astedt-Kurki P. Marital relationship and health-related quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses: a longitudinal clinical study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(13–14):2633–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Program for Promoting Advanced Appropriate Technology of Shanghai Health Commission (2019SY003), National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1711000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973145), and the “Double First-Class” University Project (CPU2018GY09). The funding body had no role in in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ identified the G-NENs from SEER database, designed the study and wrote the manuscript; YZ, QW, JC, QZ, and KZ analysed and interpreted the data; XFL and FY were responsible for the statistical analyses; XBL contributed to conception, design and funding. All authors have been involved in revising and proofreading of the manuscript. All authors listed have approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since this was a retrospective study, no ethics approval was required for analyses of these non-identifiable data.

Yu-Jie Zhou is granted permission to access the raw data with a private SEER ID (14827-Nov2017)

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No conflicts to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, YJ., Lu, XF., Zheng, K.I. et al. Marital status, an independent predictor for survival of gastric neuroendocrine neoplasm patients: a SEER database analysis. BMC Endocr Disord 20, 111 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00565-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00565-w