Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to assess the safety and feasibility of radical surgery and to investigate prognostic factors influencing in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients over the age of 80.

Methods

Between January 2010 and December 2020, 372 elderly CRC patients who underwent curative resection at the National Cancer Center were enrolled in the study. Preoperative clinical characteristics, perioperative outcomes, and postoperative pathological features were all collected.

Results

A total of 372 elderly patients with colorectal cancer were included in the study, including 226 (60.8%) men and 146 (39.2%) women. A total of 219 (58.9%) patients had a BMI < 24 kg/m2, and 153 (41.1%) patients had a BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2. The mean operation time and intraoperative blood loss were 152.3 ± 58.1 min and 67.6 ± 35.4 ml, respectively. The incidence of overall postoperative complications was 28.2% (105/372), and the incidence of grade 3–4 complications was 14.7% (55/372). In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 (HR, 2.30, 95% CI, 1.27–4.17; P = 0.006) and N1-N2 stage (HR: 2.97; 95% CI, 1.48–5.97; P = 0.002) correlated with worse CSS.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that radical resection for CRC is safe and feasible for patients over the age of 80. After radical resection, BMI and N stage were independent prognostic factors for elderly CRC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common causes of cancer death worldwide, and its morbidity and mortality are on the rise [1, 2]. With the expansion of the population and the improvement of living standards, the ageing of the population continues to increase [3]. Therefore, in clinical practice, the proportion of older patients receiving surgical treatment for colorectal cancer is increasing. Elderly patients with CRC have unusual clinicopathological features and genetic backgrounds [4, 5]. In addition, these individuals often have comorbidities such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and diabetes and often need more rigorous and prudent standardized management during the perioperative period [6]. According to the clinical consensus and guidelines, adjuvant treatment such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy is not recommended for CRC patients older than 80 years of age regardless of TNM stage, but traditional prognostic indicators may not be suitable for elderly patients with CRC over 80 years old [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Therefore, the main purpose of the present study was to demonstrate the safety and feasibility of radical surgery for CRC in elderly patients over 80 years of age, to evaluate the prognosis of elderly CRC patients without adjuvant therapy using the tumour-specific survival rate, and to comprehensively explore relevant prognostic factors.

Materials and methods

Patients

From January 2010 to December 2020, all consecutive CRC patients older than 80 years of age who underwent curative resection at the National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, were retrospectively collected and analysed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 80 or above; (2) pathologically confirmed colorectal adenocarcinoma; (3) no evidence of distant metastasis; and (4) no adjuvant therapy, such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy, after the operation. Patients who underwent emergency surgery or had other malignant tumours were excluded from the analysis. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Research. All patients provided written informed consent.

Clinical characteristics, perioperative variables, pathological results and survival outcomes for all patients were obtained from the medical records, operation records, and pathology records in our hospital database. Postoperative complications were assessed using the Clavien-Dindo classification (CD) categories and were defined as any condition that occured within 30 days after surgery that affected the normal recovery process and required conservative or surgical intervention [16]. All procedures were performed by surgeons with more than 20 years of experience in colorectal surgery. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, eighth edition) staging system was used for tumour staging.

Surgical procedures

Curative-intent surgery was performed for all patients diagnosed with CRC. All patients were placed in the modified lithotomy position, and patients underwent laparoscopic surgery or open surgery. In principle, laparoscopic surgery was performed by the five-port method under general anaesthesia. The TME and CME techniques were standardized as described previously. Briefly, the concept of TME or CME was based upon continuous sharp separation of the visceral fascial layer from the parietal layer. Then, the entire mesentery, completely covered by the visceral fascial layer, was obtained, ensuring safe exposure and ligation of the beginning of the supplying artery. The extent of surgery was determined by the location of the tumour and the pattern of underlying lymphatic metastases.

Follow-up

The long-term outcome of the present study was the 3-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) rate. All patients received a follow-up survey every 2 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months for the next 3 years. The postoperative review examinations included physical examination, biomarkers (CEA and CA-199); CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, and colonoscopy if necessary. CSS was defined as the time between the date of surgery and the date of death from cancer. Disease free survival (DFS) is defined as the time from surgery to disease recurrence or last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) is defined as the time from surgery to the time of death of the patient for any cause or the time to the last follow-up. The deadline for follow-up in this study was December 2022.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± standard deviation was used to represent quantitative data, while frequencies and percentages were used to represent categorical variables. The factors predicting CSS were identified using univariate and multivariate Cox regression models. To analyse the 3-year CSS of the patients in different groups, the Kaplan–Meier survival method was used, and significant differences in CSS were compared using the log-rank test. The variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.20) in univariate analysis were then tested in multivariate analysis using a Cox regression model, and the effect of each variable was assessed using the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics software version 24.0 was used for statistical analyses (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Short-term outcomes

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patients. Among the 372 elderly CRC patients included in this study, 226 (60.8%) were male, and 146 (39.2%) were female. Among all patients, 36 (9.7%) patients were older than 85 years. In addition, 104 (27.9%) patients had tumours in the right colon, 132 (35.5%) patients had tumours in the left colon, and 136 (36.6%) patients had tumours in rectum. The perioperative outcomes and pathological results are listed in Table 2. The mean operation time and intraoperative blood loss were 152.3 ± 58.1 min and 67.6 ± 35.4 ml, respectively. Regarding postoperative recovery, the mean postoperative hospital stay was 11.0 ± 5.6 days, and only one (0.2%) patient died in the perioperative period.

Table 3 lists the postoperative complications of the 372 elderly CRC patients. The incidence rates of overall complications, grade 1–2 complications, and grade 3–4 complications were 28.2%, 13.5%, and 14.7%, respectively. Among the overall complications, abdominal abscess (5.4%), anastomotic leakage (4.6%), and ileus (4.6%) were the most common. The most common grade 3–4 complication was urinary retention (2.4%), followed by pleural effusion (2.2%) and abdominal abscess (1.9%).

Survival analysis

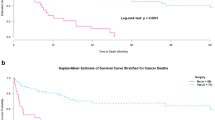

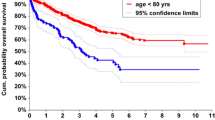

The mean follow-up period for the whole group was 60 months (range, 29–150 months). During this period, 130 of the 372 patients died (34.9%). Among them, 102 died from tumour recurrence or metastasis (27.4%). In the univariate analysis, sex, age, BMI, preoperative HGB, lifestyle habits, surgical procedure, T stage, N stage, perineural invasion, lymphatic invasion, and reoperation significantly affected CSS (P < 0.2). These variables were thus incorporated into the multivariate analysis, and the results revealed that the CSS was significantly affected by BMI (HR, 2.30, 95% CI, 1.27–4.17; P = 0.006) and N stage (HR: 2.97; 95% CI, 1.48–5.97; P = 0.002) (Table 4). The Kaplan curves showed that the CSS rate of patients was affected by the BMI (P = 0.046, Fig. 1) and N stage (P < 0.001, Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows the forest plots for CSS of elderly CRC patients based on the multivariable Cox proportional hazard model. Next, we performed prognostic analysis on DFS and OS, and found that BMI and N stage were independent prognostic factors (Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

One of the biggest challenges in healthcare is the ageing population; in 2015, the life expectancy at birth was 82.9 years, with males expected to live to 80.5 years old and females expected to live to 85.1 years old. Elderly CRC patients are regarded as a special population with unique clinicopathological characteristics, and the increase in comorbidities typically observed in this population tends to increase the potential risks during the perioperative period. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the short-term safety and long-term prognosis of radical surgery for CRC in older adults over 80 years of age.

The safety of radical surgery for elderly patients with colorectal cancer is a concern for surgeons. Prior works have reported that the incidence of overall complications in elderly patients with CRC after radical surgery is 9.9–25.4%, and the incidence of grade 3–5 complications is 6.5–20.1% [12,13,14,15]. Our study showed that the incidence rates of overall complications, grade 1–2 complications, and grade 3–4 complications were 28.2%, 13.5%, and 14.7%, respectively, which were consistent with previous reports in the literature. In addition, this study revealed that the most common overall complication after radical resection of elderly patients with CRC is an abdominal abscess (5.4%), and the most common grade 3–4 postoperative complication is urinary retention (2.4%). Before surgery, we should pay attention to and try to improve the patient's general condition, perform transfusion, supplement albumin, carry out enteral nutrition to improve the patient's nutritional status, and actively treat basic diseases such as hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes. According to the blood supply and tension of the patient's intestinal tube, the operation was performed gently, and the principle of being sterile and tumour-free was strictly followed. Postoperative nutritional support should also be actively carried out to provide sufficient raw materials for the growth of the anastomotic mouth.

Along with the increase in material wealth, the incidence of obesity has increased and become a medical and social problem. Obesity is clearly associated with the incidence of CRC [17,18,19,20,21,22], and the relationship between obesity and colorectal cancer has been previously reported but remains controversial. Several studies have reported that a high BMI is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with CRC [20, 23], while other studies have reported that a high BMI is not related to prognosis [24, 25] or is even related to a better prognosis [26, 27]. This study explores the prognostic factors related to elderly patients with CRC after curative resection, and the results show that BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 (HR, 2.30, 95% CI, 1.27–4.17; P = 0.006) and N1-N2 stage (HR: 2.97; 95% CI, 1.48–5.97; P = 0.002) were independent prognostic factors affecting CSS. Scarpa et al. grouped 595 CRC patients based on BMI and conducted postoperative follow-ups. Multivariate analysis showed that BMI > 30 kg/m2 was an independent risk factor for prognosis and recurrence after surgery (HR: 2.2; 95% CI, 1.3–3.9; P = 0.003) [28]. Doria-Rose et al. obtained similar results: patients with a high BMI, especially a BMI > 35 kg/m2, had a higher recurrence rate and poorer overall survival than those with a normal BMI [29]. The results of the above studies were basically consistent with our findings.

Over the past two decades, laparoscopic colorectal resection has grown in popularity. Laparoscopic colectomy is linked to better immunological and inflammatory responses, shorter hospitalization, and similar long-term oncologic outcomes compared to open surgery, according to a number of randomized, prospective clinical trials [30]. Nevertheless, the complexity of the pelvis' anatomical structure, the need for higher technical expertise during total mesorectal excision (TME), and the fact that colectomy preserves the autonomic nerves make minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer contentious. Laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery has been shown to be safe and to result in better functional recovery and oncological outcomes than open surgery in a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses [31]. Several recent studies have shown that laparoscopic rectal cancer resection might safely be performed irrespective of age [30, 32]. However, there is a lack of data about the long-term results of laparoscopic versus open resection in senior rectal cancer patients.

Particular attention is required when planning chemotherapy for elderly cancer patients because of reductions in organ function and pre-existing comorbidities. Most of the current randomized trials did not include many elderly patients. In 2012, Sanoff et al. [33] reported a cohort study combining four large databases of patients diagnosed with stage III CRC between 2004 and 2007. A total of 5489 patients with stage III CRC aged ≥ 75 years were analysed using covariate-adjusted and propensity score-matched proportional hazards models. Compared with surgery alone, 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy had a significant survival benefit, whereas the addition of oxaliplatin to 5-FU-based chemotherapy provided no significant benefit over 5-FU alone, although it tended to improve prognosis. In future studies, we will use our data to further explore the efficacy of adjuvant therapy in older adults.

The most significant limitation of the present study is its retrospective nature, and only 372 patients were included, which may have caused some inherent selection bias. In addition, compared to rectal cancer, colon cancer is more likely to cause systemic consumption and lower BMI, and we did not calculate colon and rectal cancer separately. Therefore, multicentre, large-scale, prospective studies are warranted to verify our results.

In conclusion, our findings show that radical resection for CRC is safe and feasible for patients over the age of 80. After radical resection, BMI and N stage were independent prognostic factors for elderly CRC patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Change history

29 March 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-01965-0

Abbreviations

- CSS:

-

Cancer-specific survival

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CD:

-

Clavien–Dindo classification

- DFS:

-

Disease free survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2014, Featuring Survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9):030.

Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2014. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(8):1650–6.

(UNFPA), U.N.P.F., http://www.unfpa.org/ageing.

Kotake K, Asano M, Ozawa H, et al. Tumour characteristics, treatment patterns and survival of patients aged 80 years or older with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(3):205–15.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145–64.

Itatani Y, Kawada K, Sakai Y. Treatment of elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:2176056.

NCCN. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Colon cancer, version 2. 2017. [EB/OL]. Fort Washington: NCCN, 2017. [2017–3–13].

Zhou S, Wang X, Zhao C, et al. Laparoscopic vs open colorectal cancer surgery in elderly patients: short- and long-term outcomes and predictors for overall and disease-free survival. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1):137.

Miguchi M, Yoshimitsu M, Shimomura M, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: A single institutional matched case-control study. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2021;14(2):200–6.

Joachim C, Godaert L, Dramé M, et al. Overall survival in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: A population-based study in the Caribbean. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;48:85–91.

Yamano T, Yamauchi S, Kimura K, et al. Influence of age and comorbidity on prognosis and application of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly Japanese patients with colorectal cancer: A retrospective multicentre study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:90–101.

Sueda T, Tei M, Nishida K, et al. Evaluation of short- and long-term outcomes following laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients aged over 80 years old: a propensity score-matched analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(2):365–75.

Sakamoto Y, Miyamoto Y, Tokunaga R, et al. Long-term outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery for elderly patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. Surg Today. 2020;50(6):597–603.

Ueda Y, Shiraishi N, Kawasaki T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in the elderly aged over 80 years old versus non-elderly: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):445.

Seow-En I, Tan WJ, Dorajoo SR, et al. Prediction of overall survival following colorectal cancer surgery in elderly patients. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;11(5):247–60.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2010;250:187–96.

Sweigert PJ, Chen C, Fahmy JN, et al. Association of obesity with postoperative outcomes after proctectomy. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):1004–9.

Liu H, Wei R, Li C, et al. BMI may be a prognostic factor for local advanced rectal cancer patients treated with long-term neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:10321–32.

Shahjehan F, Merchea A, Cochuyt JJ, et al. Body Mass Index and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:620.

Lino-Silva LS, Aguilar-Cruz E, Salcedo-Hernández RA, et al. Overweight but not obesity is associated with decreased survival in rectal cancer. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2018;22(3):158–64.

Zhang X, Wu Q, Gu C, et al. The effect of increased body mass index values on surgical outcomes after radical resection for low rectal cancer. Surg Today. 2019;49(5):401–9.

Campbell PT, Jacobs ET, Ulrich CM, et al. Case-control study of overweight, obesity, and colorectal cancer risk, overall and by tumor microsatellite instability status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(6):391–400.

Ashktorab H, Mokarram P, Azimi H, et al. Targeted exome sequencing reveals distinct pathogenic variants in Iranians with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(5):7852–66.

Ballian N, Yamane B, Leverson G, et al. Body mass index does not affect postoperative morbidity and oncologic outcomes of total mesorectal excision for rectal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1606–13.

Garcia-Oria Serrano MJ, Armengol Carrasco M, et al. Is body mass index a prognostic factor of survival in colonic cancer? A multivariate analysis. Cir Esp. 2011;89(3):152–8.

Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Hajizadeh E, Kazemnejad A, et al. Site-specific evaluation of prognostic factors on survival in Iranian colorectal cancer patients: a competing risks survival analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(5):815–21.

Hines RB, Shanmugam C, Waterbor JW, et al. Effect of comorbidity and body mass index on the survival of African-American and Caucasian patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(24):5798–806.

Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Erroi F, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for multifocal disease and recurrence after colorectal cancer surgery: a case-control study. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(10):5735–41.

Doria-Rose VP, Newcomb PA, Morimoto LM, et al. Body mass index and the risk of death following the diagnosis of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(1):63–70.

Zeng WG, Zhou ZX, Hou HR, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic versus open resection for rectal cancer in elderly patients. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):613–8.

Peltrini R, Imperatore N, Carannante F, et al. Age and comorbidities do not affect short-term outcomes after laparoscopic rectal cancer resection in elderly patients A multi-institutional cohort study in 287 patients. Updates Surg. 2021;73(2):527–37.

Manceau G, Hain E, Maggiori L, Mongin C, Prost À, Denise J, Panis Y. Is the benefit of laparoscopy maintained in elderly patients undergoing rectal cancer resection? An analysis of 446 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(2):632–42.

Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Stürmer T, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival of patients with stage III colon cancer diagnosed after age 75 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2624–34.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Key Project of National Key R & D Plan “Research on Prevention and Treatment of Common Multiple Diseases” (No. 2022YFC2505003), Key Project of National Key R & D Plan “Research on Prevention and Control of Major Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases” (No. 2019YFC1315705), China Cancer Foundation Beijing Hope Marathon Special Fund (No. LC2017L07), Medical and Health Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (No. 2017-12M-1-006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: JYJ and ZFQ. Administrative support: XW and LJW. Provision of study materials or patients: JYJ. Collection and assembly of data: ZFQ. Data analysis and interpretation: PW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each patient provided informed consent. The National Cancer Center’s Institute Research Medical Ethics Committee approved this study (NCC 2017-YZ-026, 17 October 2017). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: the author affiliations were corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, FQ., Jiang, YJ., Xing, W. et al. The safety and prognosis of radical surgery in colorectal cancer patients over 80 years old. BMC Surg 23, 45 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-01938-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-01938-3