Abstract

Background

Although pancreaticoduodenectomy with vein resection (PDVR) is widely performed in selected patients with indications, its benefits remain controversial. In this meta-analysis, we evaluate the safety and efficacy of PDVR in comparison to standard pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD).

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane as well as the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Weipu, and Wanfang databases for studies that evaluate the value of PVDR. The data of the patients who underwent PD or PDVR were analyzed using Review Manager and STATA software.

Results

In comparison with the PD group, the PDVR group had a lower R0 resection rate and higher rates of complications such as biliary fistula, reoperation rate, delayed gastric emptying, cardiopulmonary abnormalities, hemorrhage, in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality. The blood loss, duration of operation, total hospital stay is higher in PDVR group.

Conclusions

Compared to standard PD, PDVR was associated with a greater risk of some specific complications and increase the mortality rate, total hospital stay time, combine with vein resection have a lower R0 resection rate. Therefore, combine with vascular resection for pancreatic cancer needs to be carefully selected by the surgeon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for 90% of pancreatic malignant neoplasms and remains the digestive cancer with the poorest prognosis, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 7–8% [1]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is the only surgical option for the management of pancreatic head cancer. The major goal of surgery is to achieve R0 resection to be potentially curative [2]. Therefore, to ensure that the post-resection surgical margin of the tumor is negative for cancer cells (R0 resection), the use of PD is restricted to patients who have no borderline resectable lesions or locally unresectable lesions and have no metastatic disease [3, 4]. Another point in consideration is that only 15–20% of patients are candidates for surgical resection, after careful pre-therapeutic evaluation [1]. Further complications arise if the tumor invades major vascular structures adjacent to the pancreatic head, such as the portal vein (PV) and superior mesenteric vein. In some cases, PD combined with vein resection (PDVR) may be performed in an attempt to achieve a negative surgical margin [5, 6]. While PVDR is no longer considered an absolute contraindication in pancreatic head cancer, the benefits of PDVR still remain debatable. In the past, studies have shown that the median overall survival of patients undergoing PVDR for borderline and locally advanced pancreatic cancer is 22 to 24.9 months [7, 8]. On the other hand, some studies have shown that vein resection and reconstruction performed along with PD do not increase the complication rate and postoperative mortality and that the procedure is a safe and feasible option to improve the tumor resection rate [9,10,11]. In contrast, other studies have evaluated the risk of surgery and the overall survival outcomes and concluded that an operative intervention for patients with pancreatic cancer is not favorable [12, 13]. These results further emphasize the importance of determining whether PDVR actually benefits patients with borderline tumors that are not amenable to R0 resection with conventional PD; improving the R0 resection rate would enhance the cost-effectiveness of the surgery and improve survival and quality of living.

Thus, there is still some ambiguity regarding the benefits of PVDR. In this study, we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of available literature to compare the complications and survival benefits of PDVR and PD (performed with the classical technique or with preservation of the pylorus).

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search of various international and national databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Database, and Weipu database. No restrictions were placed on language or publication year. The following search terms were used as key words for the database search: “pancreaticoduodenectomy,” “duodenopancreatectomy,” “Whipple,” “vascular resection,” “venous resection,” “vein resection,” “portal vein resection,” “superior mesenteric vein resection,” “venous reconstruction,” “venous reconstruction,” and “vascular reconstruction.” The search was performed in January 2019. Moreover, additional potentially eligible studies were obtained by a manual search of the references of relevant reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Relevant clinical trials were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) The patients enrolled were those who underwent PD or PDVR for malignancy of the pancreatic head. (2) The study compared PD and PDVR in terms of surgical procedures, postoperative complication rates, tumor characteristics, duration of hospitalization, or survival rates.

The studies were excluded if they met any of the following conditions: (1) The study included patients with malignancy of the pancreatic body or tail or periampullary tumors (ampullary carcinoma, distal bile duct cholangiocarcinoma, and duodenal carcinomas), with PD, PDVR, total pancreatectomy, distal pancreatectomy, or central resection being performed according to the tumor location. (2) The papers were non-comparative studies, reviews, commentaries, or case reports. (3) Studies did not provide sufficient data. (4) Papers were duplicate publications.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

One investigator extracted all data from the selected studies, while the other independently re-extracted the data and corrected them. Disagreements were resolved by mutual consensus. Data extracted from eligible articles for analysis included the following: (1) the first author’s name, year of publication, country, and study design; (2) the number of patients in the experimental group and control group as well as their age and male ratio; and (3) data regarding surgical procedures, postoperative complication, tumor characteristics, duration of hospitalization, and survival.

Since the rate of R0 resection will be a major finding in this study, all the included studies containing the data related to R0 resection were assessed thoroughly to determine whether they referred to the AJCC guidelines to define R0 resection. According to the AJCC guidelines. R0 indicates no evidence of residual tumor. R1 indicates presence of microscopic tumor at margins, as defined by College of American Pathologists (CAP); however, the Royal College of Pathologists (RCP) R1 definition includes tumors within a 1-mm margin. Macroscopically visible tumor at margins is classified as R2.

The quality of the included studies was assessed by two independent investigators using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [14]. Each article was assigned a score between 0 and 9 for the parameters of patient selection, comparability, and outcome. A score ≥ 7 indicated that the study was of high quality with a low risk of bias.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data were presented as means and SDs for continuous variables and number of cases for dichotomous variables. All statistical analyses were carried out using RevMan 5.3 to generate the odds ratios (OR), mean difference (MD), and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with I2 ≥ 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. For studies that showed heterogeneity, we sought to determine the possible source of heterogeneity and then used the random effects model for further analysis [15, 16]. If I2 was < 50%, the fixed effects model was applied. Publication bias was estimated by visual assessment of funnel plots. All P values were two-sided, and a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

We were able to extract 3217 publications from the online databases using the search terms. In addition, 8 publications were identified by manual searching. After eliminating duplicate records and irrelevant papers by reading titles and abstracts, 260 articles were selected for full-text assessment. Finally, 30 studies comprising 12,031 patients (2186 who underwent PDVR and 9845 who underwent PD) were chosen for the meta-analysis. The study screening process has been summarized in Fig. 1. Briefly, the included studies were published between 1996 and 2017. Of the 30 included studies, 13 were from the USA; 6 were from China; 3 each were from Japan and the UK; 2 were from France; and 1 each was from Korea, Australia, and Turkey [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. All the studies included were retrospective cohort studies and investigated patients who underwent PD or PDVR for malignancy of the pancreatic head.

The results of the quality assessment of the studies, with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale scores for each study, are summarized in Table 1. Of the 30 studies, 28 were of high quality, with scores between 7 and 9; the remaining 2 studies had scores of 6 points.

Surgical procedures and hospitalization

In contrast to the PD group, the PDVR group had greater operative blood loss (MD: 201.86; 95% CI: 39.69 to 364.03; P = 0.01; I2 = 96%; Fig. 2a) and longer operative time (MD: 68.68; 95% CI: 53.63 to 83.72; P < 0.001; I2 = 92%; Fig. 2b). However, the significant heterogeneity in the studies weakened the power of the conclusion. Further, the PDVR group also had greater volume of intraoperative transfusion (MD: 385.74; 95% CI: 228.82 to 542.66; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%; Fig. 2c) and longer duration of hospitalization (MD: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.38 to 2.14; P < 0.001; I2 = 30%; Fig. 2d). No statistically significant intergroup differences were noted in terms of the length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay (MD 1.58; 95% CI: − 0.44 to 3.60, P = 0.12, I2 = 90%, Fig. 2e). Further, 23 out of the 30 included studies contain the data related to R0 resection, all these studies referred to the AJCC guidelines to define R0 resection. The PDVR group had a lower rate of R0 resection than the PD group (64.0% versus 71.3%; OR 0.64; 95% CI: 0.55 to 0.74; P < 0.001; I2 = 32%; Fig. 2f).

Mortality

The rate of in-hospital mortality (5.2% versus 2.9%; OR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.13 to 2.61; P = 0.01; I2 = 0%; Fig. 3a) as well as 30-day mortality (4.9% versus 2.6%; OR 2.02; 95% CI: 1.46 to 2.79; P < 0.001, I2 = 0%, Fig. 3b) were higher in the case of the PDVR group as compared to the PD group.

Oncological outcome

Compared to the PD group, the PDVR group had a greater tumor size (MD 2.43; 95% CI: 1.42 to 3.44; P < 0.001; I2 = 50%; Fig. 4a) and a higher neural invasion rate (67.9% versus 57.7%; OR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.43 to 2.27; P < 0.001; I2 = 47%; Fig. 4b). However, no significant differences between the PD and PDVR groups were noted for the following tumor parameters: lymph node metastasis rate (34.5% versus 54.1%; OR 1.02; 95% CI: 0.81 to 1.27; P = 0.89; I2 = 25%; Fig. 4c), vascular invasion rate (78.8% versus 18.2%; OR: 19.60; 95% CI: 0.21 to 1814.53; P = 0.02; I2 = 95%; Fig. 4d), well to moderate tumor differentiation rate (75.4% versus 75.0%; OR: 1.02; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.33; P = 0.85; I2 = 0%; Fig. 4e), or poor tumor differentiation rate (23.7% versus 23.7%; OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.77 to 1.30; P = 0.97; I2 = 0%; Fig. 4f).

Postoperative complications

In the present meta-analysis, 12 out of the 30 included studies contain data related to the occurrence rate of pancreatic fistula, 11 of them defined pancreatic fistula as a drain output of any measurable volume of fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase content greater than 3 times the serum amylase activity, which was published by International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition in 2005 [46]. Only 1 study published in 2003 defined pancreatic fistula as drainage of more than 50 ml of fluid with an amylase concentration greater than three times the upper limit of normal serum level after postoperative day 10.

With respect to postoperative complications, the current meta-analysis revealed that both the PDVR and PD groups had a similar incidence of pancreatic fistula (8.2% versus 11.0%; OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.60 to 1.04; P = 0.10; I2 = 50%; Fig. 5a), incidence of deep vein thrombosis (4.3% versus 2.1%; OR 1.09; 95% CI 0.09 to 13.75; P = 0.95; I2 = 69%; Fig. 5b), wound infection rate (7.6% versus 8.0%; OR 1.03; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.40; P = 0.85; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5c), and intra-abdominal infection rate (9.2% versus 9.3%; OR 1.21; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.66; P = 0.23; I2 = 46%; Fig. 5d).

Compared to the PD group, the PDVR group showed higher rates of complications such as biliary fistula (11.9% versus 2.5%; OR: 4.45; 95% CI: 1.98 to 9.97; P < 0.001; I2 = 44%; Fig. 5e), reoperation rate (9.6% versus 6.5%; OR 1.56; 95% CI: 1.24 to 1.97; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Fig. 5f), delayed gastric emptying (12.6% versus 10.5%, OR 1.36, 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.77, P = 0.02, I2 = 22%, Fig. 5g), cardiopulmonary abnormalities (11.0% versus 7.5%; OR 1.70; 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.36; P = 0.002; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5h), and hemorrhage (6.6% versus 2.3%, OR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.56 to 3.06; P < 0.001; I2 = 14%; Fig. 5i). In addition, some studies analyzing the rates of postoperative hemorrhage occurring at different sites showed that the rate of intra-abdominal hemorrhage (12.2% versus 3.0%; OR: 4.33; 95% CI: 2.33 to 8.06; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5j) was greater in the PDVR group, while the rate of gastrointestinal hemorrhage (9.3% versus 5.5%; OR: 1.86; 95% CI: 0.63 to 5.52; P = 0.26; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5k) was similar in both groups.

Fifteen of the 30 studies provided summarizations of the number of patients with different complications as the total complication rate; with respect to this parameter, the two groups did not show any statistically significant differences (39.3% versus 38.0%; OR 1.18; 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.39; P = 0.05; I2 = 47%; Fig. 5l).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

We further sought to examine the influence of individual studies on the results of our meta-analysis. We found that the removal of any of the included studies did not have any significant effect on the overall outcome. Most of the reported results had overlapping confidence intervals, which further ensured that our findings were not significantly influenced by any individual study. We checked for the existence of publication bias by preparing funnel plots for comparisons with more than 10 studies. No substantial asymmetry was found by visual inspection of the funnel plots (Fig. 6).

Discussion

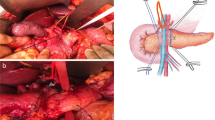

PDVR is important in clinical practice and is technically complex and requires considerable surgical skills. Invasive pancreatic cancer can easily progress, with infiltration of the adjacent nerves and important vascular structures such as the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein. Therefore, the question of whether vascular resection should be combined with surgical resection of pancreatic cancer is an important concern.

A few meta-analyses on PDVR have been reported in the past [47,48,49,50]. Song and colleagues focused on the effect of different interposition grafts in PDVR [49]. In contrast with the meta-analyses performed by F. Giovinazzo [48], Richard Bell [47] and Yu [50], our meta-analysis included the greatest amount of studies with a relatively high quality; thus, our results are more representative. In addition, we completed a comprehensive analysis for the purpose of presenting the most complete data, including surgical procedures, hospitalization, mortality, oncological outcome, and postoperative complications. Some of the parameters were assessed have not been included in previous meta-analyses, but data regarding these parameters may facilitate the decision-making process for clinicians. In terms of R0 resection rate, which is the major finding of our study, our results were consistent with those of Giovinazzo et al. [48] and Bell et al. [47]. Another difference is that we included only data pertaining to patients who had malignancy of the pancreatic head for which they underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy, which ensured the homogeneity of the research population and reduced bias. Previous analyses have shown poor survival outcomes after PDVR and do not recommend this aggressive surgical approach [51, 52]. However, PDVR continues to be performed for pancreatic cancer at some centers [27, 33, 53].

Surgeons continue to debate on whether combined vascular resection can increase the R0 resection rate of pancreatic head cancer. Analyses of the pathology outcomes showed that the PDVR group had a greater tumor size, higher neural invasion rates, and lower R0 resection rates than the PD group. However, there were no differences between the two groups in terms of lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, or type of tumor differentiation (poor or well–moderate). Taken together, these findings imply that patients in the PDVR group have a higher probability of local infiltration of disease without an increased frequency of lymph node metastasis. In addition, the type of tumor differentiation was similar for both groups.

With respect to postoperative complications, the PDVR group showed a greater rate of the biliary fistula, reoperation, delayed gastric emptying, cardiopulmonary abnormalities, hemorrhage, as well as a longer duration of hospitalization. Other investigators have also indicated that patients undergoing vascular resection have a higher rate of complications [38, 54]. The longer duration of hospitalization may be attributed to these complications. However, the two groups in our study did not show any differences in the rate of complications such as pancreatic fistula, deep vein thrombosis, wound infection, ICU stay, or total rate of complications. The incidence rate of biliary fistula in the PDVR group increased significantly, but not the pancreatic fistula. We speculated that it is the ischemic necrosis of the bile duct that lead to the difference. During the process of vascular resection and reconstruction, the PDVR group has a greater chance of blood vessels damage in the hepatoduodenal ligament than PD group, especially some tiny blood vessels and collateral circulation. This may indirectly decrease the blood supply of the residual bile duct, which may lead to bile duct ischemic necrosis and biliary fistula. Compared with bile duct, pancreas has a more sufficient blood supply and collateral circulation thanks to its innate anatomical characteristics. Therefore, the effect of PDVR on blood supply of pancreas is not as great as that of bile duct.

Patients who undergo PD also develop various complications, which may even be fatal. Combined vein resection increases the occurrence of postoperative complications in patients, thereby increasing the risks for patients undergoing PVDR during the postoperative period. However, the total rate of complications, which is defined as the proportion of patients with any kind of complication to the total patient population, did not differ between the two groups. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that a patient can have multiple complications. Therefore, although there are significant differences between PD group and PDVR group in some specific complications, the total complication rate does not necessarily differ significantly between the two groups.

The mortality associated with combined vascular resection is also a valuable point of consideration. In this meta-analysis, we observed that the 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates were indeed greater in the PDVR group. Although there were no significant differences in the total number of complications between the two groups, the rates of cardiopulmonary complication, hemorrhage, and reoperation were higher in the PDVR group than the PD group. Could the increase in mortality during these 2 periods be attributed to any of the abovementioned complications? As mentioned above, it is possible for a postoperative patient to have multiple complications at the same time, so once complications occur, the patient is often in a very serious condition and has a high mortality rate. Further investigation focusing on this question would be necessary to arrive at suitable answers.

According to NCCN guidelines [55], neoadjuvant therapy, including chemotherapy and chemoRT, has the potential to downsize tumors to increase the likelihood of a margin-free resection. It can be considered after biopsy confirmation. Most NCCN Member Institutions now prefer an initial approach for patients with borderline resectable disease that involves neoadjuvant therapy, as opposed to immediate surgery; upfront resection in patients with borderline resectable disease is no longer recommended. Neoadjuvant therapy is also sometimes used in patients with resectable disease, especially in those with high-risk features. Several trials have demonstrated that for patients with borderline resectable lesions, neoadjuvant therapy can be effective and well-tolerated [56,57,58]. In the present meta-analysis, 25 out of the 30 included studies did not present the information regarding neoadjuvant therapy; only 5 studies mentioned that some patients in PD group and PDVR group received neoadjuvant therapy, but they did not conduct a separate comparison between these patients who received neoadjuvant therapy. Regrettably, in our meta-analysis, we not able to independently analyze these patients.

Our study has a few limitations. In the pooled analysis of blood loss, duration of operation, ICU stay, vascular invasion, and DVT, the heterogeneity is relatively high. We have tried to determine the possible source of heterogeneity from the perspective of professional knowledge, but we failed to find the sources of heterogeneity. Therefore, we applied the random effect model, which may affect the credibility of the results to some extent. Another limitation is the lack of uniformity among the various studies with respect to the defining criteria for the various complications; this could lead to deviations in the data collected. Nevertheless, our study does have some merits. We employed a comprehensive search strategy and applied clearly defined, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. The most recent studies were included, and 90% of these studies were of high quality, with minimal heterogeneity of results among the studies.

Conclusions

Compared to standard PD, PDVR appears to be associated with a greater risk of some specific complications and increase the mortality rate, total hospital stay time. Combine with vein resection have a lower R0 resection rate. On the basis of the results of this meta-analysis, we recommend that combine with vascular resection for pancreatic cancer needs to be carefully selected by the surgeon.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- CAP:

-

College of American Pathologists

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PD:

-

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- PDAC:

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PDVR:

-

Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vein resection

- PV:

-

Portal vein

- RCP:

-

Royal College of Pathologists

References

Neuzillet C, Gaujoux S, Williet N, Bachet JB, Bauguion L, Colson Durand L, et al. Pancreatic cancer: French clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, ACHBT, AFC). Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(12):1257–71.

Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, Burtin P, Goere D, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v56–68.

Kleive D, Sahakyan MA, Berstad AE, Verbeke CS, Gladhaug IP, Edwin B, et al. Trends in indications, complications and outcomes for venous resection during pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2017;104(11):1558–67.

Podda M, Thompson J, Kulli CTG, Tait IS. Vascular resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary cancers. A 10 year retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;39:37–44.

Marsoner K, Langeder R, Csengeri D, Sodeck G, Mischinger HJ, Kornprat P. Portal vein resection in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is it worth the risk? Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128(15–16):566–72.

Hoshimoto S, Hishinuma S, Shirakawa H, Tomikawa M, Ozawa I, Wakamatsu S, et al. Reassessment of the clinical significance of portal-superior mesenteric vein invasion in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(6):1068–75.

Kwon D, McFarland K, Velanovich V, Martin RC 2nd. Borderline and locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma margin accentuation with intraoperative irreversible electroporation. Surgery. 2014;156(4):910–20.

Martin RC 2nd, Kwon D, Chalikonda S, Sellers M, Kotz E, Scoggins C, et al. Treatment of 200 locally advanced (stage III) pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with irreversible electroporation: safety and efficacy. Ann Surg. 2015;262(3):486–94 discussion 492-484.

Ramacciato G, Mercantini P, Petrucciani N, Giaccaglia V, Nigri G, Ravaioli M, et al. Does portal-superior mesenteric vein invasion still indicate irresectability for pancreatic carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(4):817–25.

Nakao A, Kanzaki A, Fujii T, Kodera Y, Yamada S, Sugimoto H, et al. Correlation between radiographic classification and pathological grade of portal vein wall invasion in pancreatic head cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):103–8.

Tseng JF, Raut CP, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection: margin status and survival duration. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8(8):935–49 discussion 949-950.

Nakagohri T, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Inoue K, Takahashi S. Survival benefits of portal vein resection for pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg. 2003;186(2):149–53.

Shibata C, Kobari M, Tsuchiya T, Arai K, Anzai R, Takahashi M, et al. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection for adenocarcinoma in pancreas. World J Surg. 2001;25(8):1002–5.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Jackson D, White IR, Thompson SG. Extending DerSimonian and Laird's methodology to perform multivariate random effects meta-analyses. Stat Med. 2010;29(12):1282–97.

Addeo P, Velten M, Averous G, Faitot F, Nguimpi-Tambou M, Nappo G, et al. Prognostic value of venous invasion in resected T3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma: depth of invasion matters. Surgery. 2017;162(2):264–74.

Aktekin A, Kucuk M, Odabasi M, Muftuoglu T, Gurleyik G, Ozkara S, et al. The importance of invasion and resection of superior mesenteric and portal veins in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(125):1194–8.

Banz VM, Croagh D, Coldham C, Taniere P, Buckels J, Isaac J, et al. Factors influencing outcome in patients undergoing portal vein resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38(1):72–9.

Beane JD, House MG, Pitt SC, Zarzaur B, Kilbane EM, Hall BL, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy with venous or arterial resection: a NSQIP propensity score analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2017;19(3):254–63.

Carrere N, Sauvanet A, Goere D, Kianmanesh R, Vullierme MP, Couvelard A, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal vein resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1526–35.

Castleberry AW, White RR, De La Fuente SG, Clary BM, Blazer DG 3rd, McCann RL, et al. The impact of vascular resection on early postoperative outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(13):4068–77.

Chakravarty KD, Hsu JT, Liu KH, Yeh CN, Yeh TS, Hwang TL, et al. Prognosis and feasibility of en-bloc vascular resection in stage II pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(8):997–1002.

Cheung TT, Poon RT, Chok KS, Chan AC, Tsang SH, Dai WC, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular reconstruction for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas with borderline resectability. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17448–55.

Elberm H, Ravikumar R, Sabin C, Abu Hilal M, Al-Hilli A, Aroori S, et al. Outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy for T3 adenocarcinoma: a multivariable analysis from the UK vascular resection for pancreatic cancer study group. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(11):1500–7.

Gong Y, Zhang L, He T, Ding J, Zhang H, Chen G, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy combined with vascular resection and reconstruction for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70340.

Harrison LE, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Isolated portal vein involvement in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A contraindication for resection? Ann Surg. 1996;224(3):342–7 discussion 347-349.

Howard TJ, Villanustre N, Moore SA, DeWitt J, LeBlanc J, Maglinte D, et al. Efficacy of venous reconstruction in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(8):1089–95.

Jeong J, Choi DW, Choi SH, Heo JS, Jang KT. Long-term outcome of portomesenteric vein invasion and prognostic factors in pancreas head adenocarcinoma. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(4):264–9.

Kaneoka Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M. Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma: prognostic value of the length of venous resection. Surgery. 2009;145(4):417–25.

Kelly KJ, Winslow E, Kooby D, Lad NL, Parikh AA, Scoggins CR, et al. Vein involvement during pancreaticoduodenectomy: is there a need for redefinition of “borderline resectable disease”? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(7):1209–17 discussion 1217.

Kurosaki I, Hatakeyama K, Minagawa M, Sato D. Portal vein resection in surgery for cancer of biliary tract and pancreas: special reference to the relationship between the surgical outcome and site of primary tumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(5):907–18.

Leach SD, Lee JE, Charnsangavej C, Cleary KR, Lowy AM, Fenoglio CJ, et al. Survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy with resection of the superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Br J Surg. 1998;85(5):611–7.

Martin RC 2nd, Scoggins CR, Egnatashvili V, Staley CA, McMasters KM, Kooby DA. Arterial and venous resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: operative and long-term outcomes. Arch Surg. 2009;144(2):154–9.

Menon VG, Puri VC, Annamalai AA, Tuli R, Nissen NN. Outcomes of vascular resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy: single-surgeon experience. Am Surg. 2013;79(10):1064–7.

Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakashima A, Kondo N, et al. Benefit of portal or superior mesenteric vein resection with adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with pancreatic head carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(4):414–21.

Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with en bloc portal vein resection for pancreatic carcinoma with suspected portal vein involvement. World J Surg. 2004;28(6):602–8.

Ravikumar R, Sabin C, Abu Hilal M, Bramhall S, White S, Wigmore S, et al. Portal vein resection in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a United Kingdom multicenter study. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):401–11.

Roch AM, House MG, Cioffi J, Ceppa EP, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, et al. Significance of portal vein invasion and extent of invasion in patients undergoing Pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(3):479–87 discussion 487.

Sgroi MD, Narayan RR, Lane JS, Demirjian A, Kabutey NK, Fujitani RM, et al. Vascular reconstruction plays an important role in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(2):475–80.

Toomey P, Hernandez J, Morton C, Duce L, Farrior T, Villadolid D, et al. Resection of portovenous structures to obtain microscopically negative margins during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma is worthwhile. Am Surg. 2009;75(9):804–9 discussion 809-810.

Turley RS, Peterson K, Barbas AS, Ceppa EP, Paulson EK, Blazer DG 3rd, et al. Vascular surgery collaboration during pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular reconstruction. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(5):685–92.

Wang F, Gill AJ, Neale M, Puttaswamy V, Gananadha S, Pavlakis N, et al. Adverse tumor biology associated with mesenterico-portal vein resection influences survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(6):1937–47.

Wang WL, Ye S, Yan S, Shen Y, Zhang M, J W, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with portal vein/superior mesenteric vein resection for patients with pancreatic cancer with venous invasion. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14(4):429–35.

Zhao X, Li LX, Fan H, Kou JT, Li XL, Lang R, et al. Segmental portal/superior mesenteric vein resection and reconstruction with the iliac vein after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Int Med Res. 2016;44(6):1339–48.

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138(1):8–13.

Bell R, Ao BT, Ironside N, Bartlett A, Windsor JA, Pandanaboyana S. Meta-analysis and cost effective analysis of portal-superior mesenteric vein resection during pancreatoduodenectomy: impact on margin status and survival. Surg Oncol. 2017;26(1):53–62.

Giovinazzo F, Turri G, Katz MH, Heaton N, Ahmed I. Meta-analysis of benefits of portal-superior mesenteric vein resection in pancreatic resection for ductal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2016;103(3):179–91.

Song W, Yang Q, Chen L, Sun Q, Zhou D, Ye S, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy combined with portal-superior mesenteric vein resection and reconstruction with interposition grafts for cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(46):81520–8.

Yu XZ, Li J, Fu DL, Di Y, Yang F, Hao SJ, et al. Benefit from synchronous portal-superior mesenteric vein resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):371–8.

Roder JD, Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Carcinoma of the periampullary region: who benefits from portal vein resection? Am J Surg. 1996;171(1):170–4 discussion 174-175.

van Geenen RC, ten Kate FJ, de Wit LT, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Segmental resection and wedge excision of the portal or superior mesenteric vein during pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2001;129(2):158–63.

Friess H, Kleeff J, Fischer L, Muller M, Buchler MW. Surgical standard therapy for cancer of the pancreas. Chirurg. 2003;74(3):183–90.

Muller SA, Hartel M, Mehrabi A, Welsch T, Martin DJ, Hinz U, et al. Vascular resection in pancreatic cancer surgery: survival determinants. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(4):784–92.

Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Bain A, Behrman SW, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15(8):1028–61.

Esnaola NF, Chaudhary UB, O'Brien P, Garrett-Mayer E, Camp ER, Thomas MB, et al. Phase 2 trial of induction gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and cetuximab followed by selective capecitabine-based chemoradiation in patients with borderline resectable or unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(4):837–44.

Katz MH, Crane CH, Varadhachary G. Management of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2014;24(2):105–12.

Katz MH, Shi Q, Ahmad SA, Herman JM, Marsh Rde W, Collisson E, et al. Preoperative modified FOLFIRINOX treatment followed by Capecitabine-based Chemoradiation for borderline Resectable pancreatic cancer: Alliance for clinical trials in oncology trial A021101. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(8):e161137.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PC primarily designed the work, drafted the article, finished the actual writing; ZD organized this research and performed the Meta-analysis and intensive revision of manuscript; MLJ offers the essential technical support and assistance for statistical analysis; CYL and ZHW formulated the search strategy and performed the literature searching, finished the selection of included studies and scored each article according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; PZ completed chart drawing and the correction of manuscript; LC contributed to the study design, critical revision and finalization of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. PC and ZD contributed equally to this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Formal ethics approval is not required for a systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, C., Zhou, D., Meng, L. et al. The value of combined vein resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma: a meta-analysis. BMC Surg 19, 84 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0540-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0540-6