Abstract

Background

Gastric fistulas, bleeding, and strictures are commonly reported after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), that increase morbidity and hospital stay and may put the patient’s life at risk. We report our prospective evaluation of application of synthetic sealant, a modified cyanoacrylate (Glubran®2), on suture rime, associated with omentopexy, to identify results on LSG-related complications.

Methods

Patients were enrolled for LSG by two Bariatric Centers, with high-level activity volume. Intraoperative recorded parameters were: operative time, estimated intraoperative bleeding, conversion rate. We prospectively evaluated the presence of early complications after LSG during the follow up period. Overall complications were analyzed. Perioperative data and weight loss were also evaluated. A control group was identified for the study.

Results

Group A (treated with omentopexy with Glubran®2) included 96 cases. Control group included 90 consecutive patients. There were no differences among group in terms of age, sex and Body Mass Index (BMI). No patient was lost to follow-up for both groups. Overall complication rate was significantly reduced in Group A. Mean operative time and estimated bleeding did not differ from control group. We observed three postoperative leaks in Group B, while no case in Group A (not statistical significancy). We did not observe any mortality, neither reoperation. Weight loss of the cohort was similar among groups. In our series, no leaks occurred applying omentopexy with Glubran®2.

Conclusion

Our experience of omentopexy with a modified cyanoacrylate sealant may lead to a standardized and reproducible approach that can be safeguard for long LSG-suture rime.

Trial registration

Retrospective registration on clinicaltrials.gov PRS, with TRN NCT03833232 (14/02/2019).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bariatric surgery is currently considered a stable and safe solution for morbid obesity. Different surgical options are available, and they are continuously evolving, influenced by new reports of literature [1, 2]. Real question is today comprehension, prevention and ideal treatment of major complications, reducing morbidity and mortality [3]. In particular, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is actually the most performed bariatric procedure in most countries and since 2009 the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) estabnilished LSG as distinct bariatric procedure [4]. Moreover, a number of serious, sometimes fatal, complications must be considered, like gastric fistulas or suture line dehiscence (leaks), bleeding, and strictures [5, 6]. Leaks/gastric fistulae, although appearing in a low percentage of patients, increase morbidity and hospital stay and may put the patient’s life at risk. Many risk factors and preventive technical details, in order to reduce this event, have been proposed, with discordant results [6,7,8]. We report our prospective evaluation of application of synthetic sealant, a modified cyanoacrylate [N-Butil-Cyanoacrylate (NBCA) + Metacrylosysolfolane (MS), a co-monomer owned by GEM S.r.l. – Viareggio (LU) –Italy], defined Glubran® 2, on suture rime, associated with omentopexy, to identify results on LSG-related complications.

Methods

The prospective randomized trial is designed with the aim to verify the effectiveness of the Glubran®2 used in its spray application, according to manufacturer’s indications, to perform the omentopexy of the staple line to prevent and reduce early complications after LSG. single-blind randomization was explained: a single surgeon, in enrollment phase, assigned patient to case or control group, after adequate communication of randomization to all patients. The surgeon that performed procedure only knew if patient was randomized to case group (LSG with omentopexy with Glubran®2) or to control group (LSG without omentopexy with Glubran®2). Control group was identified for the study with simple randomization, considering patients treated with LSG during same period. Patients of case and control groups were not paired. Same recording was performed for both groups. Patients were enrolled for LSG by two Bariatric Centers, with high-level activity volume, after multidisciplinary evaluation: inclusion criteria, according with international guidelines [1, 9], was body mass index (BMI) of greater than 40 kg/m2 or > 35 with at least one co-morbidity, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia or diabetes, age ≥ 18 years old, medically unfit for surgical intervention, absence of active gastric disease, of uncontrolled medical or psychiatric conditions, and signed written informed consent. Bariatric procedure was performed according with standardized four-trocars technique [10]. All surgeons involved had a proved experience for bariatric surgery, and have completed learning curve.

The size of the boogie to be used for calibration ranged from 42 to 48 Fr, among two groups. In case group, after gastric partition and confirming correct closure of mechanical section (performed with Endo-Gia, varying depth of stapler, from blue to green charge, according with gastric level), we applied a layer of the synthetic sealant on all rime suture and chose an omentum flap to place and cover it. We carefully controlled absence of gastric rotation with omentum flap, or any tension on the resected stomach. In control group, we reinforced staple line with buttressing (bovine pericardium) of mechanical stapler, or with running suture of the rime alone, indifferently. A recording of type of reinforcing was performed, also if not pertinent to study.

Anthropometric data recorded were: age, weight, BMI, presence of comorbidities. Intraoperative recorded parameters were: operative time, estimated intraoperative bleeding (in ml), conversion rate. We prospectively evaluated the presence of early complications after LSG during the follow up period (30 days from intervention). Considered complications were staple line leakage/gastric fistula, postoperative bleeding, intraabdominal abscess, cardiopulmonary failure, and all other complications. In order to considering effects and real impact of mentioned events, we also evaluated length of hospital stay, rate of readmission, rate of reintervention, overall mortality at 30 days. Weight loss was recorded at 15 and 30 days, as excess weight loss percent (EWL%) and as reduction of BMI.

The continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The demographic data and perioperative data were compared using the student’s t and Mann- Whitney U tests for continuous variables, while Fisher’s exact test was used to determine any statistical significance for the categorical variables. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Results

Enrollment of case and control group was performed between January and April 2017. Case group (treated with omentopexy with Glubran®2) included 96 cases. All patients were enrolled for bariatric surgery and LSG was for all indicated (Table 1). Control group included 90 patients treated with LSG without omentopexy with Glubran®2. In all cases, laparoscopic procedure was performed according with standardized technique.

There were no differences among group in terms of age, sex and BMI. No patient was lost to follow-up for both groups.

Intraoperative data and follow-up are explained in Table 2: overall complication rate was significantly reduced in case group. In 68.8% (62 cases) of control group buttressing of bovine pericardium was applied, while in other cases (31.2%; 28 cases) suturing was preferred. Mean operative time and estimated bleeding did not differ from control group. All cases of postoperative bleeding, recorded in case and control groups, were solved with blood transfusion and conservative therapy. We did not observe any postoperative leak in case group, until the 30-days follow-up, while three leaks in control group, recovered on 3th and 4th postoperative day, were recorded (p: 0.08). All were treated with conservative approach and supportive medical therapy, until to radiologic disappearance. Number of patients does not enhance to any statistical significance. No difference of complication rate was observed for two types of reinforcing (suturing or buttressing), in control group (data not shown).

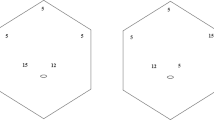

We did not observe any mortality, neither reoperation, at a mean follow-up of 16.4 months for Group A and of 17.5 months, for Group B. Regarding to postoperative data, mean drain removal time, mean hospitalization and reintervention rate did not significantly differ from control group (Table 2). Weight loss of the cohort, synthetized in Fig. 1, was similar among groups.

Discussion

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is a standardized bariatric procedure in all Occidental countries. Its mechanism of action include early satiety and gastrointestinal hormonal variation, including reduction of ghrelin levels [4, 5]. In relation to dramatic results on weight loss, also on long-term follow-up, LSG is recently overcoming on all major bariatric procedure, as single procedure, with a minority of cases in which a second malabsorptive procedure should be proposed [3, 4]. Moreover, LSG is associated with high-risk complications, that determine also a prolonged hospitalization, increasing home care, and significant mortality risk [5].

Based on the data of more than 12.000 LSGs, the International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement 2011 showed the leak rate was 1.06% [11], while overall complication rate is near to 15% [12]. From the revision of the literature the leak rate can vary between 1 and 3% for primary procedure, with an overall leak associated mortality of 9% [6] [12, 13].

Considering pathogenesis of this complication, early leaks within 48 h are caused by a technical defect: stapler misfire, or wrong staple size for the tissue, are possible factors [14]. Late leaks, occurring after several days, are surely related to tissue ischemia caused by tension on the anastomosis, distal bowel obstruction, or hematoma. In both situations, the intraluminal pressure is demonstrated and determinant for fistulization [14].

In a multicenter experience with 2834 patients, leaks post LSG were related to abnormal vascularization, bleeding or thermal injuries. Demonstrated risk factors were increased age, male, gender, sleep apnea and revisional surgery. Actually, one of the most discussed topic is the best prevetion of this complication [15].

Various preventive techniques have been proposed. The use of closed suction drain routinely near the staple line, despite that it is performed by the majority of surgeons, may not be helpful for diagnosis [16]. The size of the boogie to be used for calibration is also a subject of controversies, ranging between 32 and 60 Fr: a large systematic review taking 4888 patients and another large meta-analysis of 9991 patients suggested that larger boogie size may decrease the leak rate, but statistical significance for boogie size on leak rate is lacking [17]. Staple line reinforcement has commonly diffused, in order to reducing weak points of suture and bleeding risk, with different products on stapler or putting after resection, such as fibrin sealants. These were investigated in majority of studies, with good impact in term also of decreasing leakage rate, on the rationale the polymerization process also acts as a sealant to prevent leaks [6, 18]. All large randomized prospective trials and meta-analysis showed no significant difference between reinforcement (by oversewing or buttress on stapler) and simple section, in term of leakage rate [19, 20]. On the other hand, most authors agree that reinforcement decreases bleeding risks. On this line, Gagner et al., in a powerful review on 88 papers, shows in the no reinforcement group an overall complication rate of 8.9%, and confirmed that buttressing LSG suture did not determine a statistical evidence on leaks [21]. Almost all device making for reinforcing determine generally a faster procedure compared with oversewing suture, that is suitable for experienced surgeons [22].

Conversely, omentopexy has been historically evaluated to reinforce perforated peptic ulcer, or after bronchial dehiscence. Local application on gastrointestinal anastomosis has been reported: in all cases an omentum flap is located on sutured tract with reinforcing stitches [23, 24]. The only bariatric report on omentopexy reported a possible effect on gastrointestinal symptoms, after LSG, without results on mitigating food discomfort [25]. Recently, some other authors believe that in duodenal switch omentopexy over lateral gastric staple line and around as much of the gastrostomy to buttress it together drainage and feeding jejunostomy could be efficacious to prevent ischemic leaks [26]. Moreover, the effect of the staple line omentopexy using a sealant synthetic glue despite the sutures to prevent postsurgical LSG complications has never been investigated before. Cyanoacrylate sealant seems to be comparable to fibrin glue in staple line reinforcement, in recent comparative analysis [27]. We hypothesize that NBCA+MS sealant (Glubran®2) may add a major action on staple for bleeding, and, either fixing omentum either enhancing adhesive action, reduce risk of leak. It has proved its adhesive effect, confirming as excellent sealant and hemostatic agent. All these properties are necessary to guarantee an effective buttressing of the staple line.

Our comparative prospective evaluation seems indicate that omentopexy with NBCA+MSsealant is a safe and reproducible technique, with good results on bleeding and leaks. We found a significant results on overall complications, despite no difference was observed for specific ones, on single statistical evaluations. In detail, leak rate was higher for control group, although without significance, enhancing value of sealant and omentopexy for reinforcing suture rime.

Although significant results are not evident, operative time is not conditioned, neither weight loss. Operative time is comparable to classic LSG; similarly technical aspect of omentopexy is not determinant, neither it determined a more complex procedure. Conversely, double effect, haemostatic and on tension suture, seems to be guaranteed. It has discussed the possible adhesive effect of omentopexy, in case of bariatric second-time: in this case, enlargement of sleeve is a key to perform with good safety a gastrointestinal anastomosis and/or a new gastric section, also including minimal residual sealant in the excluded stomach. Increase of adherence risk is not clearly demonstrated for all hemostatic agent. Larger studies are mandatory, to confirm our new observation, that, differently from numerous trial about fibrin glue and oversewing techniques, can be easily standardized and is more physiological for action of omentum. In fact, rate of employed glue is very poor compared to fibrin products.

Conclusion

LSG is a safe technique, but staple line-associated complications can be life-threatening. In this series, no leaks occurred applying omentopexy with NBCA+MS glue (Glubran®2), from the very beginning of the surgeons’ experience in LSG. Actually, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that routine oversewing of the staple line or reinforcement with buttressing material after LSG decreases these complications. Proper mentoring, and performance of surgery in appropriate settings are good approaches to decreasing complications. Our experience of omentopexy with amodified cyanoacrylate sealant may lead to a standardized and reproducible approach that can be safeguard for long LSG-suture rime.

Abbreviations

- ASMBS:

-

American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

- EWL%:

-

Excess weight loss percent

- LSG:

-

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

- MS:

-

Metacrylosysolfolane

- NBCA:

-

N-Butil-Cyanoacrylate

References

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;292(14):1724–37 Review. Erratum in: JAMA Apr 13;293(14):1728. PMID: 15479938. 2004 Oct 13.

Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219–34 Epub2013 Feb 8. PMID: 23163728.

Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8(8):CD003641 CD003641.pub4. PMID: 25105982.

Clinical IssuesCommittee of the AmericanSociety for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Updated position statement on sleeve gastrectomy as a bariatric procedure. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(1):1–5 Epub 2009 Nov 17 PMID: 1993974.

van Rutte PW, Smulders JF, de Zoete JP, Nienhuijs SW. Outcome of sleeve gastrectomy as a primary bariatric procedure. Br J SurgMay. 2014;101(6):661–8 PMID: 2472301.

Himpens J, Dobbeleir J, Peeters G. Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Ann Surg. 2010;252(2):319–24 PMID: 20622654.

Varban OA, Greenberg CC, Schram J, Ghaferi AA, Thumma JR, Carlin AM, Dimick JB, Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Surgical skill in bariatric surgery: Does skill in one procedure predict outcomes for another? Surgery. 2016;160(5):1172–81 Epub 2016 Jun 17. PMID: 27324569.

Arman GA, Himpens J, Dhaenens J, Ballet T, Vilallonga R, Leman G. Long-term (11+years) outcomes in weight, patient satisfaction, comorbidities, and gastroesophageal reflux treatment after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(10):1778–86 Epub2016 Jan 19. PMID: 27178613.

Fried M, Yumuk V, Oppert JM, Scopinaro N, Torres A, Weiner R, Yashkov Y, Frühbeck G, International Federation for Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders-European Chapter (IFSO-EC); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO); European Association for the Study of Obesity Obesity Management Task Force (EASO OMTF). Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24(1):42–55 PMID: 24081459.

Hayes K, Eid G. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, surgical technique and perioperative care. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96(4):763–71 PMID: 27473800.

Rosenthal RJ, International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, Baker RS, Basso N, Bellanger D, Boza C, El Mourad H, France M, Gagner M, Galvao-Neto M, Higa KD, Himpens J, Hutchinson CM, Jacobs M, Jorgensen JO, Jossart G, Lakdawala M, Nguyen NT, Nocca D, Prager G, Pomp A, Ramos AC, Rosenthal RJ, Shah S, Vix M, Wittgrove A, Zundel N. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):8–19 Epub 2011 Nov 10. PMID:22248433.

Osland E, Yunus RM, Khan S, Alodat T, Memon B, Memon MA. Postoperative Early Major and Minor Complications in Laparoscopic Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy (LVSG) Versus Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) Procedures: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Obes Surg. 2016;26(10):2273–84 PMID: 26894908.

Gagner M, Hutchinson C, Rosenthal R. Fifth International Consensus Conference: current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):750–6 Epub2016 Jan 25. PMID: 27178618.

El-Sayes IA, Frenken M, Weiner RA. Management of leakage and stenosis after sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery. 2017;162(3):652–61 Epub2017Jul 8. PMID: 28693759.

Sakran N, Goitein D, Raziel A, Keidar A, Beglaibter N, Grinbaum R, Matter I, Alfici R, Mahajna A, Waksman I, Shimonov M, Assalia A. Gastric leaks after sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter experience with 2,834 patients. SurgEndosc. 2013;27(1):240–5 Epub 2012 Jun 30. PMID: 2275228.

Deitel M, Gagner M, Erickson AL, Crosby RD. Third International Summit: Current status of sleeve gastrectomy. SurgObesRelat Dis. 2011;7(6):749–59 Epub2011 Aug 10.PMID: 21945699.

Aurora AR, Khaitan L, Saber AA. Sleeve gastrectomy and the risk of leak: a systematic analysis of 4,888 patients. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(6):1509–15 Epub 2011 Dec 17. PMID: 22179470.

Musella M, Milone M, Maietta P, Bianco P, Pisapia A, Gaudioso D. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: efficacy of fibrin sealant in reducing postoperative bleeding. A randomized controlled trial. Updates Surg. 2014;66(3):197–201 Epub2014 Jun 25. PMID: 24961471.

Carandina S, Tabbara M, Bossi M, Valenti A, Polliand C, Genser L, Barrat C. Staple Line Reinforcement During Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Absorbable Monofilament, Barbed Suture, Fibrin Glue, or Nothing? Results of a Prospective Randomized Study. J GastrointestSurg. 2016;20(2):361–6 PMID: 26489744.

D'Ugo S, Gentileschi P, Benavoli D, Cerci M, Gaspari A, Berta RD, Moretto C, Bellini R, Basso N, Casella G, Soricelli E, Cutolo P, Formisano G, Angrisani L, Anselmino M. Comparative use of different techniques for leak and bleeding prevention during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter study. SurgObesRelat Dis. 2014;10(3):450–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.018 Epub 2013 Nov 12.PMID: 24448100.

Gagner M, Buchwald JN. Comparison of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leak rates in four staple-line reinforcement options: a systematic review. SurgObes Relat Dis. 2014;10(4):713–23 Epub 2014 Jan 28. PMID: 24745978.

Taha O, Abdelaal M, Talaat M, Abozeid M. A Randomized Comparison Between Staple-Line Oversewing Versus No Reinforcement During Laparoscopic Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017;28(1):218–25.

MacFayden BV Jr, Wolfe BM, McKernan JB. Laparoscopic management of the acute abdomen, appendix, and small and large bowel. SurgClin North Am. 1992;72(5):1169–83. PMID: 1388304.

Levashev YN, Akopov AL, Mosin IV. The possibilities of greater omentum usage in thoracic surgery. Eur J CardiothoracSurg. 1999;15(4):465–8. PMID: 10371123.

Afaneh C, Costa R, Pomp A, Dakin G. A prospective randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of omentopexy during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in reducing postoperative gastrointestinal symptoms. SurgEndosc. 2015;29(1):41–7 Epub 2014 Jun 25. PMID:24962864.

Greenbaum DF, Wasser SH, Riley T, Juengert T, Hubler J, Angel K. Duodenal switch with omentopexy and feeding jejunostomy-a safe and effective revisional operation for failed previous weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(2):213–8 Epub 2010 Nov 10. PMID: 21215708.

Martines G, Digennaro R, De Fazio M, Capuano P. Cyanoacrylate sealant compared to fibrin glue in staple line reinforcement during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Pilot prospective observational study. G Chir. 2017;38(1):50–2 PMID: 28460205.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and to participate

Informed written consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Since technique and products involved for the study are currently used for this procedure, we obtained a specific authorization by Ethical Committee of the two Hospitals, University Hospital of Salerno and University Hospital of Padova, in order to perform prospective study.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This article did not receive sponsorship for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Surgery, Volume 19 Supplement 1, 2019: Updates in Endocrine Surgery: part two. The full contents of the supplement are available at https://bmcsurg.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have been involved for study design, acquisition and analysis of data, drafting and critical revision of manuscript, subdivided for two centers involved, University Hospital of Salerno and University Hospital of Padova, Italy. VP, ST, MR1, MR2, and AM. enrolled, treated and followed patients on University Hospital of Salerno. MR2 corrected first English version. AA and MF. Treated and followed patients on University Hospital of Padua. VP. and ST. collected data and completed statistical analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

A specific written consent for data publication was signed by each patient involved.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, nor financial and non-financial competing interests related to study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pilone, V., Tramontano, S., Renzulli, M. et al. Omentopexy with Glubran®2 for reducing complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: results of a randomized controlled study. BMC Surg 19 (Suppl 1), 56 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0507-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0507-7