Abstract

Background

Some studies have reported an association between complications and impaired long-term survival after cancer surgery. We aimed to investigate how major complications are associated with overall survival after gastro-esophageal and pancreatic cancer surgery in a complete national cohort.

Methods

All esophageal-, gastric- and pancreatic resections performed for cancer in Norway between January 1, 2008, and December 1, 2013 were identified in the Norwegian Patient Registry together with data concerning major postoperative complications and survival.

Results

When emergency cases were excluded, there were 1965 esophageal-, gastric- or pancreatic resections performed for cancer in Norway between 1 January 2008, and 1 December 2013. A total of 248 patients (12.6 %) suffered major postoperative complications. Complications were associated both with increased early (90 days) mortality (OR = 4.25, 95 % CI = 2.78–6.50), and reduced overall survival when patients suffering early mortality were excluded (HR = 1.23, 95 % CI = 1.01–1.50).

Conclusions

Major postoperative complications are associated with impaired long-term survival after gastro-esophageal and pancreatic cancer surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Major complications after surgery have negative effects on health-related quality of life [1], length-of-stay [2] and resource utilization [2]. Major complications may preclude or delay adjuvant cancer treatment [3]. In addition, long-term survival may be negatively affected [4–7].

Khuri and co-workers [5] found that patients experiencing complications from surgery had a markedly reduced long-term survival even when those who died within 30 days after surgery were excluded from analysis. As summarized in a recent meta-analysis, these findings have been corroborated by several reports, but others again have failed to show this connection [6]. It has been suggested that major complications could have long-standing suppressive effects on a patient’s immune system and thereby rendering them more susceptible to cancer recurrence [4, 5, 7–9].

Investigating a possible long-standing detrimental effect of postoperative complications on survival after cancer surgery is challenging: Major complications after modern surgery are relatively uncommon and therefore large cohorts are needed for analysis. There is no consensus on the correct cut-off for early mortality and there may be several factors that affect both susceptibility to complications and decreased overall survival - factors that have to be adequately adjusted for. Naturally, an interventional trial is impossible to conduct.

Patient’s level of education is a known indicator of important factors like physical activity and smoking habits [10], factors that are associated with both increased morbidity and impaired survival after surgery [11].

The aim of this study was to investigate whether major complications after gastro-esophageal and pancreatic surgery for cancer are associated with impaired long-term survival or early mortality only. We also aimed to investigate if such an association was influenced by patient’s level of education.

Methods

Cohort identification

A database of surgical procedures, major postoperative complications and survival was extracted from the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR). The Norwegian Patient Registry enables patients to be tracked from one stay to another, thus allowing for identification of an early complication occurring at a local hospital following transfer from a tertiary hospital where index surgery had been performed. All Norwegian hospitals must submit data to the Norwegian Patient Registry for registry and reimbursement purposes. In the present study, we included data from admissions during 2008–2013. Data on educational level were extracted from Statistics Norway, the Norwegian central bureau of statistics.

We identified all resections of the esophagus, stomach and pancreas in the six-year period from January 1, 2008 to December 1, 2013. Complications within 28 days after surgery (to the end of 2013) are therefore included in the data material. Data on overall survival until June 30, 2014 were retrieved, thus even the last patient subject to surgery included would have seven months follow-up, if not dying. Operations and reoperations were identified from their Nomesco classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP) code (2014). NCSP is available for download at http://www.nordclass.se/ncsp.htm.

Only cases with an appropriate cancer diagnosis (ICD-10: C15*, C16* and C25* respectively, where * denotes all sub-codes) applied within eight weeks from surgery were included. Emergency cases were excluded to obtain a cohort of patients that were reasonably fit at index surgery.

Overall survival was defined as survival from index surgery. Major complications were defined as equivalent to Accordion score IV or higher, equaling Clavien-Dindo score IIIb or higher [12, 13], i.e. a re-operation in general anesthesia for a complication, and/or single- or multiple organ failure [12]. We did not attempt to identify less severe complications, as these would be difficult to extract from Norwegian Patient Registry data.

All stays in this database (containing an eligible index operation) were coupled with any subsequent stay at any Norwegian hospital with an admission date within 28 days from discharge from the index stay. Hospital stays (single or coupled) containing one or more major complications were identified. This was done by identification of one of the following procedure codes at index or subsequent stay (NCSP): Reoperation for wound dehiscence (JWA00), for deep infection (JWC00/01), for deep hemorrhage (JWE00/01/02), for anastomotic dehiscence (JWF00/01), reoperation for other causes (JWW96/97/98) or if a tracheostomy was performed (GBB00/03). Also, a major complication was identified from the use of one of the following diagnoses during index or subsequent stays (ICD-10): Bleeding, hematoma or circulatory chock following a procedure (ICD-10: T81.0, T81.1, T81.3).

Validation of algorithm

The algorithms to identify complications were constructed in several wider variations and then validated against hand searched patient files. A tendency to over-score complications (identifying Accordion III or Clavien-Dindo IIIa as “major complications”) when using the entire complications section (ICD-10: T81*) was avoided when some sub-codes (ICD-10: T81.2, T81.4, T81.5, T81.6, T81.7, T81.8 and T81.9) were removed from the algorithm. A comparison of the yield from our refined search strings with hand searched patient files in a four-year cohort at our own hospital (150 patients) showed a 100% match in both number of resections and rate of major complications (Accordion IV or higher).

Definition of variables

Age at index surgery was analyzed both as a continuous variable and with a cut-off of 65 years. Educational level was divided into higher and lower education. Higher education was defined as education beyond primary and lower secondary school. Surgical resections were stratified into esophageal-, gastric- and pancreatic resections.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistics software, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA. For comparison of characteristics between different groups and categories, Student t-test for continuous data and Pearson chi-square test for categorical data were used. Logistic regression was used for analyzing associations between age, gender, educational level, type of resection and the risk of a major postoperative complication as well as early (90 days) mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival plots with log-rank test and Cox proportional hazard (PH) regression analysis were used for analysis of overall survival. Both methods were used, as the proportional hazards assumption for Cox regression (constant relative hazards over time) was not met when analyzing the relationships between educational level and survival (Fig. 1) and when analyzing the relationship between complications and survival (Fig. 2). Cox proportional hazard regression analysis using attained age as the time variable was also used as a supplement, as the proportional hazards assumption was met in this situation. P-values according to the log-rank-test are given in the figures (the Kaplan-Meier survival plots) whereas p-value according to the Cox regression analyses (including the analyses adjusted for possible confounders) in Table 3. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The association between major postoperative complications and overall survival. Kaplan-Meier plots with subjects at risk. Survival probability on the Y-axis and time in months on the X-axis. Dotted lines denotes patients without any postoperative complications. Solid lines denotes patients who suffered one or more major postoperative complication. a All patients included. b Patients alive more than 90 days only

Ethics

Centre of Clinical Documentation and Evaluation has concession from the Norwegian Data Protection Authority and confidentiality exemption from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK –Northern chapter). The concession provides access to unique personal data from Norwegian Patient Registry with information about patients treated at Norwegian hospitals in the period 2008–2013. Encrypted patient serial numbers makes it possible to describe patient pathways involving several hospitals and over several years. The concession also includes permission to pair education data from Statistics Norway.

Results

Patient selection and characteristics

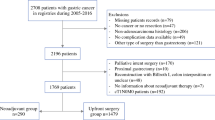

A total of 3080 esophageal-, gastric and pancreatic resections were performed between 1January 2008 and 1December 2013. Of these, 2792 resections were scheduled. Of the 2792 scheduled resections, 1965 were performed for cancer; 331 esophageal resections (16.8 %), 974 gastric resections (49.6 %) and 660 pancreatic resections (33.6 %). Seventy percent of the gastric resections and almost all of the esophageal (99 %) and pancreatic resections (98 %) were performed at the six university hospitals (only four university hospitals perform esophageal resections). Forty percent of esophageal and half of the pancreatic resections were performed at Norway’s largest hospital, Oslo University Hospital (OUS). Only 13% of the gastric resections were performed at OUS.

During the follow-up period, 975 (49.6 %) patients died. Median age at index operation was 68 years. A total of 248 patients (12.6 %) suffered one or more major postoperative complication and 37 (14.9 %) of these patients died within 90 days. Consequently, 1717 patients (87.4 %) did not suffer any major complications within 28 days after surgery and 68 (4.0 %) of these patients died within 90 days. Estimated median survival in the entire cohort was 31 months (Table 1) and the estimated five-year survival rate was 37.3 %.

Major postoperative complications

There were no statistically significant linear changes in the rate of complications from 2008 to 2013 (p = 0.319). The highest (17.2 %) and lowest (11.1 %) complication rate was seen in esophageal resections and gastric resections, respectively (Table 2). Type of resection and lower educational level (OR = 1.41, 95 % CI = 1.02–1.95, p = 0.039) were associated with major postoperative complications. The association with educational level was also present when adjusted for age, gender and type of resection (OR = 1.53, 95 % CI = 1.10–2.13, p = 0.013).

Early mortality

One-hundred-and-five (5.3 %) patients died within 90 days after surgery. Suffering one or more postoperative complications was strongly associated with 90-day mortality (OR = 4.25, 95 % CI = 2.78–6.50, p < 0.001).

Overall survival

There was no association between educational level and overall survival (p = 0.145) (Fig. 1) and this conclusion did not change after multivariable adjustment for age, gender and type of resection (HR = 1.06, 95 % CI = 0.91–1.23, p = 0.475).

Postoperative complications were negatively associated with overall survival both with all patients included (Fig. 2, panel a) (p < 0.001) and when the first 90 days of the follow-up period (Fig. 2, panel b) (p = 0.040) were excluded. The survival curves (Fig. 2) suggest that the impact of major complications attenuate with time from the index surgery and p-value for interaction with time of follow up was <0.001. The estimated five-year survival rate was 38.2 % in patients who did not suffer any major postoperative complications compared to 30.6 % in patients who did. Major postoperative complications were associated with 23 % higher long term (i.e., excluding early) mortality (HR = 1.23, 95 % CI = 1.01–1.40, p = 0.040) (Table 3). Multivariable adjustment for age, gender, type of resection and educational level did not alter the association between major postoperative complications and overall survival (Table 3). Neither did use of attained age (instead of time in study) as the time variable in the Cox regression analysis. There were no significant interaction between type of resection and complications in the survival analysis, i.e., the association between complications and survival were not statistically significantly different according to type of resection. The association between postoperative complications and survival was similar across all types of resections (Fig. 3). Neither hospital volume (OUS vs. other university hospitals; analyzed for esophageal and pancreatic resections) or hospital teaching status (university hospital vs. non-university hospital; analyzed for gastric resections) did affect the association between complications and survival (data not shown).

The association between major postoperative complications and overall survival. Esophageal, gastric and pancreatic resections analyzed separately. Kaplan-Meier plots with subjects at risk. Survival probability on the Y-axis and time in months on the X-axis. Dotted lines denotes patients without any postoperative complications. Solid lines denotes patients who suffered one or more major postoperative complication. a Esophageal resections. b Gastric resections. c Pancreatic resections

Discussion

We present a complete national six-year cohort of gastro-esophageal and pancreatic resections for cancer in Norway with major complications and survival. Suffering one or more major postoperative complications was associated with both considerably increased early mortality and statistically significant decreased long-term survival. Educational level did not affect the relationship between complications and survival.

Several studies have demonstrated an association between postoperative complications and decreased survival [5, 6]. This has led to theories suggesting an immune-suppressive effect of postoperative complications that might lead to cancer recurrence [5, 8, 9]. A recent meta-analysis reported a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.28 for decreased overall survival after any postoperative complication [6], the cut-offs for early mortality were not reported [6]. We found a similar risk of decreased survival associated with major complications if patients suffering early mortality were excluded (HR = 1.23). In this large, nationwide population-based cohort, we found some evidence to support theories concerning long-standing detrimental effects of complications on survival after gastro-esophageal and pancreatic cancer surgery.

Most studies exploring the issue of postoperative complications and long-term survival have either not used a cut-off at all or a 30-days mortality cut-off to exclude patients with fatal complications [5, 6, 8, 9]. Only a few studies report a cut-off for early mortality of 90-days [7]. Therefore, patients who died later than 30 days, but still arguably as a direct result of their complications may still have been included in the analysis, making it more difficult to address a possible long-standing detrimental effect of non-fatal complications.

Reductions in both overall survival and disease-free survival have been observed in colorectal cancer patients who suffered major complications [7, 8, 14]. In a large study of colon cancer patients, complications were associated with precluded or delayed adjuvant chemotherapy [3]. In the same study, complications were not associated with reduced survival if adjuvant chemotherapy were given within appropriate time-limits [3]. While chemotherapy is an important element to achieve increased survival in resectable stage III and IV colon cancer [15, 16], the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term survival in gastro-esophageal and pancreatic cancer is variable and less certain [17, 18].

The avoidance of postoperative complications is of utmost importance as complications adversely affect health-related quality of life [1] and survival [5, 6]. Complications may preclude or delay adjuvant chemotherapy [3]. Do complications make patients more susceptible to cancer recurrence and therefore cause decreased longevity? Large prospective registries with detailed information on disease-stage, comorbidity, time of recurrence and cause of death are needed to fully investigate this question. The registries used for our study contain complete national data and a large number of patients but lack information on cancer stage and disease-specific survival.

Conclusions

In a national setting, major postoperative complications are associated with both early mortality and decreased long-term survival after gastro-esophageal and pancreatic cancer surgery. Systematic quality improvement to avoid complications may improve the poor prognosis associated these cancers.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Centre of Clinical Documentation and Evaluation has concession from the Norwegian Data Protection Authority and confidentiality exemption from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK –Northern chapter). The concession provides access to unique personal data from Norwegian Patient Registry with information about patients treated at Norwegian hospitals in the period 2008–2013. Encrypted patient serial numbers makes it possible to describe patient pathways involving several hospitals and over several years. The concession also includes permission to pair education data from Statistics Norway.

Availability of data and materials

Centre of Clinical Documentation and Evaluation has concessions that provide access to unique personal data from Norwegian Patient Registry. According to Norwegian rules and regulations, these data cannot be made publically available.

Abbreviations

- NPR:

-

Norwegian Patient Registry

- NCSP:

-

Nomesco Classification of Surgical Procedures

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition

- OUS:

-

Oslo University Hospital

References

Brown SR, Mathew R, Keding A, et al. The impact of postoperative complications on long-term quality of life after curative colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2014;259(5):916–23.

Knechtle WS, Perez SD, Medbery RL, et al. The Association Between Hospital Finances and Complications After Complex Abdominal Surgery: Deficiencies in the Current Health Care Reimbursement System and Implications for the Future. Ann Surg. 2015;262(2):273–9.

Krarup PM, Nordholm-Carstensen A, Jorgensen LN, et al. Anastomotic Leak Increases Distant Recurrence and Long-Term Mortality After Curative Resection for Colonic Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2014;259(5):930–8.

Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, et al. Poor survival rate in patients with postoperative intra-abdominal infectious complications following curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1575–83.

Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, et al. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):326–41.

Pucher PH, Aggarwal R, Qurashi M, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of postoperative in-hospital morbidity on long-term patient survival. Br J Surg. 2014;101(12):1499–508.

Artinyan A, Orcutt ST, Anaya DA, et al. Infectious postoperative complications decrease long-term survival in patients undergoing curative surgery for colorectal cancer: a study of 12,075 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261(3):497–505.

Mavros MN, de Jong M, Dogeas E, et al. Impact of complications on long-term survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2013;100(5):711–8.

Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, et al. Postoperative complications influence prognosis and recurrence patterns in periampullary cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37(9):2234–41.

Isaacs SL, Schroeder SA. Class - the ignored determinant of the nation’s health. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1137–42.

Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Harling H, et al. The impact of socioeconomic factors on 30-day mortality following elective colorectal cancer surgery: a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1248–56.

Porembka MR, Hall BL, Hirbe M, et al. Quantitative weighting of postoperative complications based on the accordion severity grading system: demonstration of potential impact using the american college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(3):286–98.

Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):177–86.

Mirnezami A, Mirnezami R, Chandrakumaran K, et al. Increased local recurrence and reduced survival from colorectal cancer following anastomotic leak: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;253(5):890–9.

Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1797–806.

Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1007–16.

Bringeland EA, Wasmuth HH, Fougner R, et al. Impact of perioperative chemotherapy on oncological outcomes after gastric cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101(13):1712–20.

Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2499–509.

Acknowledgements

No additional investigators were involved in this research project.

Funding

This investigation and manuscript preparation received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: EKA, BKJ, KL. Data acquisition: FO and BU. Data analysis: FO, BU, BKJ. Data interpretation and manuscript preparation, editing and final approval: All authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Aahlin, E.K., Olsen, F., Uleberg, B. et al. Major postoperative complications are associated with impaired long-term survival after gastro-esophageal and pancreatic cancer surgery: a complete national cohort study. BMC Surg 16, 32 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-016-0149-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-016-0149-y