Abstract

Background

To systematically review the association between knee abduction kinematics and kinetics during weight-bearing activities at baseline and the risk of future anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury.

Methods

Systematic review and meta-analysis according to PRISMA guidelines. A search in the databases MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, EMBASE and Scopus was performed. Inclusion criteria were prospective studies including people of any age, assessing baseline knee abduction kinematics and/or kinetics during any weight-bearing activity for the lower extremity in individuals sustaining a future ACL injury and in those who did not.

Results

Nine articles were included in this review. Neither 3D knee abduction angle at initial contact (Mean diff: -1.68, 95%CI: − 4.49 to 1.14, ACL injury n = 66, controls n = 1369), peak 3D knee abduction angle (Mean diff: -2.17, 95%CI: − 7.22 to 2.89, ACL injury n = 25, controls n = 563), 2D peak knee abduction angle (Mean diff: -3.25, 95%CI: − 9.86 to 3.36, ACL injury n = 8, controls n = 302), 2D medial knee displacement (cm; Mean diff:: -0.19, 95%CI: − 0,96 to 0.38, ACL injury n = 72, controls n = 967) or peak knee abduction moment (Mean diff:-10.61, 95%CI: - 26.73 to 5.50, ACL injury n = 54, controls n = 1330) predicted future ACL injury.

Conclusion

Contrary to clinical opinion, our findings indicate that knee abduction kinematics and kinetics during weight-bearing activities may not be risk factors for future ACL injury. Knee abduction of greater magnitude than that observed in the included studies as well as factors other than knee abduction angle or moment, as possible screening measures for knee injury risk should be evaluated in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is a common injury in team sports [1, 2] and often leads to serious consequences for the individual, including pain, functional limitations, reduced quality of life and lower activity levels [3, 4] that may persist several years post injury [4]. There is also an increased risk of developing early-onset osteoarthritis of the knee [5].

Most ACL injuries occur during non-contact episodes [6], typically within 50 milliseconds after foot contact, with the foot planted on the ground with a nearly extended knee together with trunk lean and knee abduction [7, 8]. The main function of the ACL is to provide mechanical stability to the knee during movements by preventing anterior tibial translation and rotational load [9, 10]. Several in vitro studies have also shown that the knee abduction moment is a major contributor to ACL strain and is, thus, suggested to play an important role in the ACL injury mechanism [11,12,13]. Added to this, some studies have reported individuals with ACL deficiency to exhibit an increased knee abduction angle compared to non-injured individuals [14,15,16]. This, together with the result of one early study establishing a relationship between increased knee abduction angle and knee abduction moment, respectively, and a higher risk of ACL injury in women [17], have given rise to knee abduction being widely accepted as an undesirable movement pattern [6, 8]. That women are reported to perform functional tasks with greater knee abduction than men [18], as well as having a higher risk of sustaining an ACL injury [1] has further perpetuated this hypothesis.

Based on the evidence-based reasoning presented above, numerous studies have been conducted to (1) determine the factors that contribute to knee abduction during weight-bearing activities [19], and (2) to incorporate exercises to reduce knee abduction into ACL injury prevention programs [6, 8]. However, the evidence for an association between knee abduction kinematics and/or kinetics and ACL injury risk seems to be conflicting [17, 20] and to date the findings from all studies investigating knee abduction as a risk factor for future ACL injury have not been synthesized. Thus, the aim of this study was to systematically review knee abduction kinematics and kinetics during weight-bearing activities at baseline as a possible risk factor for future ACL injury development.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analyses were conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines. The study protocol was pre-registered (PROSPERO CRD42017067254; n.b., knee abduction kinetics were added to the protocol after registration).

Literature search and study selection

Search strategy

A systematic search in MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, EMBASE and Scopus was performed in September 2018 and updated in August 2019 using the terms as follows:

(“Anterior Cruciate Ligament”[Mesh]) OR “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries”[Mesh])) OR lower extremity[Title/Abstract]) OR ACL injur*) OR Anterior cruciate ligament injur*)) AND ((risk factor*[Title/Abstract]) OR injury risk[Title/Abstract])) AND (((((((knee abduction[Title/Abstract]) OR biomechanic*[Title/Abstract]) OR mechanic*[Title/Abstract]) OR kinematic*[Title/Abstract] OR kinetic*[Title/Abstract]) OR valgus[Title/Abstract]) OR alignment[Title/Abstract]) OR displacement[Title/Abstract]).

In addition, reference lists of all relevant articles were searched for additional studies. No language or publication date restrictions were applied.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were: 1) Prospective longitudinal studies, 2) including healthy men and/or women of any age, 3) assessing baseline knee abduction in degrees and/or medial knee displacement (MKD) in cm with 2D and/or 3D motion analysis, and/or by visual observation, and/or knee abduction moment during any weight-bearing activity for the lower extremity, and 4) recording of ACL injuries sustained during the follow-up period. Animal studies, in vitro studies, case studies, retrospective studies, conference abstracts, review papers, editorials and letters were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two researchers (AC & EA) independently screened the titles, abstracts and full papers against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by a consensus discussion between AC and EA, and if required with a third researcher (MWC). The following data were extracted from the studies: Authors, publication date, number of participants, sex, age, activity level, sport, measurement tool (2D or 3D motion analysis, or visual observation), knee abduction angle in degrees or MKD in cm, knee abduction moment, time point during the movement at which an assessment was made (e.g., on contact with the ground or the peak angle or moment during the movement), functional task, follow-up period, ACL injury data and effect measure. A meta-analysis was performed if there were two or more studies that included the same outcome, e.g. assessed knee abduction kinematics with the same measurement tool (e.g., 3D motion analysis) at the same time point during the weight-bearing activity (e.g., peak knee abduction). If we could not retrieve sufficient data from a paper to determine inclusion/exclusion or for the purposes of data extraction, the authors were contacted and additional data were requested.

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 2.2.064 (Englewood, USA) was used for meta-analyses. The effect measure was calculated as the mean (SD) difference in baseline knee abduction angle in degrees at initial contact (IC) and/or peak knee abduction, in MKD in cm or in peak abduction moment (N.m.) between those who sustained an ACL injury and those who did not. A random effect model was used due to expected heterogeneity between studies, such as task, follow-up duration, gender, age, sport, and activity level. All meta-analysis and corresponding forest plots were weighted under the random effect model, taking both within study variance and between study variance (Tau2) into account [21]. Between-studies effect measure heterogeneity was calculated with the Q-test and expressed as I2-statistics. A p-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In addition, to evaluate the robustness of our meta-analyses, sensitivity analyses for different subgroups (i.e., sex, age, task and follow-up period) were performed when possible.

Quality assessment and publication bias

The checklist previously used by Cronström et.al [18, 19]. adapted from the original checklist by Downs and Black [22] was used for assessment of general methodological quality of the included studies (Online resource A, Table 1). Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed for quality by two independent reviewers (AC) and (EA). Publication bias was explored using Funnel plots with trim and fill if ten or more studies were included in the meta-analysis [23, 24].

Results

Study selection

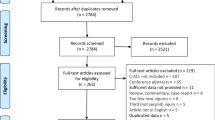

A total of 2867 abstracts were screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Twenty full-text articles were then screened. Of those, 10 articles were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Of the remaining ten articles, three articles [35,37,37] used the total number of lower extremity injuries as an outcome and one study [38] used a combined measure of knee abduction and trunk lean. The authors of these articles were contacted and additional data for ACL injury and knee abduction specifically were requested, and were retrieved for three of the four studies [35, 37, 38]. Finally, nine articles proceeded to quality assessment and were included in the review [17, 20, 35, 37,38,39,40,41,42] (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

In six studies, 3D knee abduction angle was assessed at different time points; at IC (n = 4) [17, 20, 39, 41], peak knee abduction (n = 3) [17, 35, 41] or across the entire landing phase [42]. In two studies, 2D peak knee abduction angle was assessed [37, 38]. 2D MKD in cm at IC and peak was assessed in one study [40]. The 2D MKD excursion in cm (the difference between IC and peak MKD) was assessed in three studies [20, 39, 40]. Eight studies assessed knee abduction kinematics at baseline during either a double-leg vertical drop jump [17, 20, 35, 39, 41, 42] or single-leg vertical drop jump [38, 40] and one study evaluated knee abduction angle during a single-leg squat [37]. Four studies assessed peak knee abduction moment during a double-leg vertical drop jump in females [17, 20, 39, 42]. Seven studies included only females involved in either high school team sports [17, 39, 40] or playing at an elite level [20, 35, 38, 42] and two studies included both male and female athletes (playing level not specified) [37] or individuals enrolled at military service academies in the USA [41] (Table 1).

Synthesis of results

The meta-analysis showed that there was no difference in baseline 3D knee abduction angle at IC, 3D peak knee abduction angle, 2D peak knee abduction angle, 2D MKD excursion (cm) or peak knee abduction moment between those who subsequently sustained an ACL injury and those who did not (Figs. 2 and 3).

Mean difference in baseline 2D peak knee abduction angle (ACL injury n = 8, controls n = 302), 3D knee abduction angle at initial contact (ACL injury n = 66, controls n = 1369), 3D peak knee abduction angle (ACL injury n = 25, controls n = 563) and medial knee displacement (ACL injury n = 72, controls n = 967) between those who sustained an ACL injury and those who did not. Abd = knee abduction, B = both males and females, F = females, SLS = single-leg squat, SDJ = single-leg drop jump, VDJ = double-leg vertical drop jump, 2D peak = 2D peak knee abduction angle, 3D IC = 3D knee abduction angle at initial contact, 3D peak = 3D peak knee abduction angle, MKD = medial knee displacement

Two articles [40, 42] included factors not eligible for meta-analysis and the results for these articles are reported in Table 2.

The sensitivity analyses revealed that limiting the studies to those that included only females, or the vertical drop jump task only, or a mean age > 15 years or a follow-up period > 1 year did not change the results (Online resource B).

Heterogeneity and risk of bias

I2 ranged between 13.2 and 90.6%, indicating low to high heterogeneity between studies [43]. The quality of the included studies ranged from 58 to 84%, indicating moderate to high methodological quality (Table 1 and Online resource C, Table 1). There were too few studies in each meta-analysis to explore publication bias using Funnel plots with trim and fill imputations [24].

Discussion

The result from this systematic review and meta-analysis revealed no association between baseline knee abduction kinematics or kinetics during vertical drop jumps or squats and the risk of sustaining a future ACL injury. No studies were available in other weight-bearing tasks. Our conclusions are based on a large sample (1979 participants across 8 studies), with low to high heterogeneity, and were unaffected in our sensitivity analyses suggesting that our findings hold true irrespective of participant age, sex, or movement task.

A greater knee abduction angle and/or knee abduction moment during weight-bearing activities has commonly been suggested to represent undesirable mechanics and contribute to future ACL injury [6, 8]. Yet, across the 8 studies included in our meta-analyses, we found no difference in 2D knee abduction angle, 3D knee abduction angle, MKD or peak knee abduction moment at baseline between those who sustained a future ACL injury and those who did not. In addition to the possibility that knee abduction kinematics and kinetics are not at all associated with ACL injury risk, one explanation for this apparent contradiction may relate to the magnitude of knee abduction observed in the included studies. The earliest published study to examine the prospective relationship between knee abduction and ACL injury [17], reported that greater knee abduction angle and moment, respectively, were predictive of subsequent ACL injury. In this study, participants that subsequently sustained an ACL injury exhibited ~ 5 degrees of knee abduction at initial contact with the ground, ~ 9 degrees of peak knee abduction and 45 N.m. peak knee abduction moment [17]. Interestingly, all subsequent studies reporting 3D knee abduction mechanics that were included in our meta-analyses report only around 2 degrees of peak abduction for all participants, including those that subsequently sustained an ACL injury [20, 39, 41] and between 21 and 37 N.m. peak abduction moment [20, 39], and found neither measure to be predictive of future ACL injury. Conceivably, the findings of Hewett and colleagues [17], in combination with earlier evidence from cadaver knees [44,45,46], lead to the development and adoption of ACL injury prevention training specifically targeting knee abduction in weight-bearing activities; this has subsequently been highlighted in numerous reviews and consensus statements [8, 18, 47, 48]. As a result, the magnitude of knee abduction mechanics observed in the vast majority of studies included in our analyses may not be sufficient to present as a risk factor for ACL injury. Supporting this, the study by Krosshaug et.al., [20] included in our analysis reports that approximately 40% of the included participants in their study “reported to have implemented preventive training as part of their routine during the season”. It is, thus, possible that the results of our meta-analyses are rather a consequence of successful injury prevention training in the last decade, than that excessive knee abduction and/or kinetics are not risk factors for ACL injury. On the other hand, although injury prevention programs may have decreased the amount of knee abduction exhibited during activities, there seem to be no decrease in the incidence of ACL injury during the same time period [49, 50], indicating that knee abduction may play a minor role in ACL injury.

An alternative explanation for our findings could be that instead of a linear relationship between knee abduction and ACL injury risk there may be a non-linear relationship with a certain cut-point beyond which knee abduction is associated with ACL injury risk. None of the studies included in this review have used break-point analysis to investigate if certain thresholds of knee abduction were associated with elevated ACL injury risk. Although greater knee abduction has been postulated to increase the risk of injury, there is no consensus regarding the amount of knee abduction that is considered excessive enough to amplify ACL injury risk. Fox et al., determined normative values for knee abduction angle during a vertical drop jump to 0.30 ± 5.0 degrees for IC and 8.71 ± 9.1 degrees for peak knee abduction [51], implying that the participants in the studies included in this review were all in the normal range of knee abduction, i.e., concurrent with the amount of knee abduction in the general population, which may further mask possible associations between knee abduction and injury risk. Given the lack of an injury risk threshold, it is also not clear if there is an elevated risk of knee injury in individuals presenting with knee abduction at the higher end of the normal range that has been postulated. Furthermore, most studies investigating knee abduction as a risk factor for ACL injury assess knee abduction during a drop vertical jump. The vertical drop jump is a bilateral task and may not reflect movements when injury occurs and does not seem to detect sex differences in knee abduction compared to other tasks [18]. Thus, it is possible that this task is not challenging enough to capture the amount of knee abduction that may be associated with injury. Other more challenging tasks, such as cutting tasks, should, therefore, be considered when evaluating knee abduction as a risk factor for ACL injury in future studies.

Increased knee abduction compared to both non-injured individuals and the contra-lateral leg is reported after ACL injury [14,15,16]. Although several video analysis studies report that knee abduction seems to be involved in the ACL injury mechanism in females [52,53,54], it is not possible to elucidate the exact time point of the injury on video recordings. Given that the main purpose of the ACL is to provide mechanical stability to the knee [9, 10], it is not clear if the knee abduction (or valgus collapse) observed at the time for injury causes the injury or is due to decreased joint stability as a result of the ACL tear [52,53,54]. Although some recent cadaveric studies report an association between increased knee abduction moment and ACL failure [55, 56], in support of the latter, a recent systematic review on bone bruises assessed with MRI after ACL injury [57] concludes that knee abduction occurs after the ACL is ruptured, not before. It should, however, be noted that in the same systematic review a high number (approx. 70%) of bone bruises were located on the lateral side, which could indicate presence of knee abduction at the time of injury. Nevertheless, the conclusion of that meta-analysis is further supported by a study that investigated knee kinematics before and after ACL injury and found participants that sustained an ACL injury to perform a drop vertical jump with significantly greater knee abduction angle 2 years after injury compared to their performance at baseline prior to the injury [41]. Thus, it is possible that persistent deficiencies in motor control after injury cause further risk of sustaining also a second ACL injury [20, 31]. It should be noted that although 3D motion analysis was used in most of the studies the way in which knee abduction is quantified may still vary substantially. Differences in how joint axes are defined [58], the kinematic modelling approach employed (direct versus inverse kinematics) [59], and inertial properties used to determine joint kinetics [60] are all known to result in differences in the magnitude of knee abduction measured during functional activities. Similarly, marker placement locations may be differentially influenced by soft tissue artefact, impacting upon the validity and reliability of the marker model used [61]. While there is recent evidence of good to excellent within and between session reliability for both knee abduction angle and knee abduction moment during double-leg vertical drop jump using 3D analysis [62], this may not hold true for all studies included in our review. Despite these variations in the approach used to quantify knee abduction and the variance in the data that this may produce, mostly low to moderate heterogeneity was observed across our meta-analyses, suggesting that the cumulative effect of these differences upon our findings was minimal.

This review has some limitations. We pooled studies on females alone and those that included both men and women, had different follow-up periods as well as different weight-bearing tasks in some of our analyses. While these primary analyses may have masked associations between knee abduction and injury risk, our sensitivity analyses demonstrate that this is unlikely to be the case. Likewise, we pooled studies including participants of different ages (i.e., ≤15 years or > 15 years) and different activity levels. Neuromuscular and biomechanical differences between males and females during early puberty and through maturation have been suggested to play a role for ACL injury risk in young females [8]. Importantly however, our sensitivity analysis including the only two studies on young females (i.e. ≤15 years) revealed no association between 3D knee abduction at baseline and future ACL injury. Taken together, the result from this review applies across sexes, tasks, age and follow-up period. It was, however, not possible to perform a sensitivity analysis for activity level (elite athletes versus high school athletes), since there were too few studies using the same outcome. The two studies that included high school athletes [17, 40] reported that the participants that sustained an ACL injury had increased 3D knee abduction angles (IC and peak) [17] and increased 2D MKD (IC and peak) [40] at baseline compared to those who did not sustain an injury. Thus, we cannot rule out that factors contributing to knee injury may differ between those on an elite level compared to being active on a lower level. This is worthy of further investigation. Furthermore, the meta-analyses are only able to show if a greater or smaller amount of knee abduction is associated with future ACL injury and not if a certain threshold of knee abduction is related to an elevated injury risk. We included studies that employed differing methodologies to quantify knee joint mechanics. Of note, knee abduction angles were obtained with both 2D and 3D motion analysis systems; knee abduction moments were exclusively obtained with 3D motion analysis. While there is evidence that knee abduction angles measured in 2D are strongly correlated with knee abduction measured in 3D [63,64,65], the 2D measure also incorporates components of sagittal and transverse plane rotation and thus our findings with regard to 2D knee abduction kinematics are likely, to a small extent, to reflect the underlying sagittal and transverse plane knee kinematics. In light of these differences we did not pool the results from 2D and 3D studies. Yet, given the strong relationship between 2D and 3D knee abduction, taken together these results both support the absence of a predictive effect of baseline knee abduction on ACL injury development. Moreover, some of the meta-analysis included a relatively low number of individuals with ACL injury, e.g., the analysis on 2D peak knee abduction (n = 8). Performing meta-analysis with a low number of events may increase the risk of overestimating the effect [66]. The 2D peak knee abduction analysis did also include two different tasks, a single-leg squat and a single-leg drop landing with too few studies to perform a sensitivity analysis. Although individuals seem to perform these tasks with a similar amount of knee abduction [67, 68], it is possible that the use of different tasks may have masked findings from individual tasks. Thus, some caution is needed when interpreting the 2D peak knee abduction results. Furthermore, our heterogeneity analysis using I2 statistics revealed mostly low to moderate heterogeneity between studies. The analysis for peak knee abduction moment was, however, associated with high heterogeneity. To account for expected heterogeneity, we have performed all analysis under the random effect model that incorporates both within study and between study variance in the analysis. It has also been suggested that the I2 statistics may be subject to bias when only a small amount of studies are included in the analysis [69]. Thus, the I2 statistics presented in this review should be interpreted with caution. Also, there were too few studies included to be able to explore publication bias. However, since it is more likely that studies reporting no significant results are the studies that are not being published, this is unlikely to have an influence on our result. Finally, this review only included knee abduction kinematics and kinetics as possible risk factors for ACL injury. Several studies highlight that the mechanisms of ACL injury are in fact multifactorial and that several combined factors, such as knee abduction and internal rotation kinematics and kinetics, but also neuromuscular control of the hip and trunk may contribute to the injury mechanism [8, 12, 56, 70,71,72,73]. Even though knee abduction kinematics and kinetics alone cannot predict injury risk, future studies will reveal if knee abduction may contribute to knee injury when combined with other risk factors, such as those described above.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that neither baseline knee abduction kinematics or kinetics during weight-bearing activity may predict future ACL injuries. This is contrary to popular clinical opinion and the findings of the earliest published study examining this relationship. It is possible that as a result of the successful implementation of ACL injury prevention programs in organized sport, emphasizing a knee position in line with the hip and ankle, that knee abduction is not a risk factor for ACL injury development across these cohorts. Future studies are warranted to investigate whether knee abduction during more demanding tasks, in combination with other risk factors and/or in other cohorts, such as recreational athletes, is associated with future primary as well as second ACL injury.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- MKD:

-

Medial knee displacement

- 2D:

-

Two dimensional

- 3D:

-

Three dimensional

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CI:

-

Confidence intervall

- IC:

-

Initial contact

- N.m.:

-

Newton meter

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- cm:

-

Centimeter

- Kg:

-

Kilogram

- BMI:

-

Bodymass index

- NR:

-

Not reported

- abd:

-

Abduction

- B:

-

Both males and females

- F:

-

Females

- SLS:

-

Single-leg squat

- SDJ:

-

Single-leg drop jump

- VDJ:

-

Double-leg vertical drop jump

References

Walden M, Hagglund M, Werner J, Ekstrand J. The epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injury in football (soccer): a review of the literature from a gender-related perspective. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(1):3–10.

Beynnon BD, Vacek PM, Newell MK, Tourville TW, Smith HC, Shultz SJ, Slauterbeck JR, Johnson RJ. The effects of level of competition, sport, and sex on the incidence of first-time noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1806–12.

Faltstrom A, Hagglund M, Kvist J. Patient-reported knee function, quality of life, and activity level after bilateral anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2805–13.

Whittaker JL, Woodhouse LJ, Nettel-Aguirre A, Emery CA. Outcomes associated with early post-traumatic osteoarthritis and other negative health consequences 3-10 years following knee joint injury in youth sport. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(7):1122–9.

Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, Rollins M, Bach BR Jr, MacDonald P. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301.

Renstrom P, Ljungqvist A, Arendt E, Beynnon B, Fukubayashi T, Garrett W, Georgoulis T, Hewett TE, Johnson R, Krosshaug T, et al. Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: an International Olympic Committee current concepts statement. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(6):394–412.

Stuelcken MC, Mellifont DB, Gorman AD, Sayers MG. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in elite women’s netball: a systematic video analysis. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(16):1516–22.

Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Paterno MV, Quatman CE. Mechanisms, prediction, and prevention of ACL injuries: cut risk with three sharpened and validated tools. J Orthop Res. 2016;34(11):1843–55.

Butler DL, Noyes FR, Grood ES. Ligamentous restraints to anterior-posterior drawer in the human knee. A biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(2):259–70.

Bicer EK, Lustig S, Servien E, Selmi TA, Neyret P. Current knowledge in the anatomy of the human anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(8):1075–84.

Bates NA, Nesbitt RJ, Shearn JT, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Knee abduction affects greater magnitude of change in ACL and MCL strains than matched internal Tibial rotation in vitro. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(10):2385–96.

Bates NA, Myer GD, Shearn JT, Hewett TE. Anterior cruciate ligament biomechanics during robotic and mechanical simulations of physiologic and clinical motion tasks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2015;30(1):1–13.

Kiapour AM, Kiapour A, Goel VK, Quatman CE, Wordeman SC, Hewett TE, Demetropoulos CK. Uni-directional coupling between tibiofemoral frontal and axial plane rotation supports valgus collapse mechanism of ACL injury. J Biomech. 2015;48(10):1745–51.

Yamazaki J, Muneta T, Ju YJ, Sekiya I. Differences in kinematics of single leg squatting between anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients and healthy controls. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(1):56–63.

Trulsson A, Garwicz M, Ageberg E. Postural orientation in subjects with anterior cruciate ligament injury: development and first evaluation of a new observational test battery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(6):814–23.

Tengman E, Grip H, Stensdotter A, Hager CK. Anterior cruciate ligament injury about 20 years post-treatment: a kinematic analysis of one-leg hop. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(6):818–27.

Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt RS Jr, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, van den Bogert AJ, Paterno MV, Succop P. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(4):492–501.

Cronstrom A, Creaby MW, Nae J, Ageberg E. Gender differences in knee abduction during weight-bearing activities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2016;49:315–28.

Cronstrom A, Creaby MW, Nae J, Ageberg E. Modifiable factors associated with knee abduction during weight-bearing activities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(11):1647–62.

Krosshaug T, Steffen K, Kristianslund E, Nilstad A, Mok KM, Myklebust G, Andersen TE, Holme I, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. The vertical drop jump is a poor screening test for ACL injuries in female elite soccer and handball players: a prospective cohort study of 710 athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(4):874–83.

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, H R. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Duval S, Tweedy R. A nonparametric “trim and fill method” of accounting for publication bias in meta-analyses. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:89–98.

Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. Cmaj. 2007;176(8):1091–6.

Soderman K, Alfredson H, Pietila T, Werner S. Risk factors for leg injuries in female soccer players: a prospective investigation during one out-door season. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(5):313–21.

Vacek PM, Slauterbeck JR, Tourville TW, Sturnick DR, Holterman LA, Smith HC, Shultz SJ, Johnson RJ, Tourville KJ, Beynnon BD. Multivariate analysis of the risk factors for first-time noncontact ACL injury in high school and college athletes: a prospective cohort study with a nested, matched case-control analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1492–501.

Padua DA, DiStefano LJ, Beutler AI, de la Motte SJ, DiStefano MJ, Marshall SW. The landing error scoring system as a screening tool for an anterior cruciate ligament injury-prevention program in elite-youth soccer athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50(6):589–95.

Chorba RS, Chorba DJ, Bouillon LE, Overmyer CA, Landis JA. Use of a functional movement screening tool to determine injury risk in female collegiate athletes. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010;5(2):47–54.

van der Does HT, Brink MS, Benjaminse A, Visscher C, Lemmink KA. Jump landing characteristics predict lower extremity injuries in indoor team sports. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(3):251–6.

Dudley RI, Pamukoff DN, Lynn SK, Kersey RD, Noffal GJ. A prospective comparison of lower extremity kinematics and kinetics between injured and non-injured collegiate cross country runners. Hum Mov Sci. 2017;52:197–202.

Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, Hewett TE. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1968–78.

Capin JJ, Khandha A, Zarzycki R, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Gait mechanics and second ACL rupture: implications for delaying return-to-sport. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(9):1894–901.

Amraee D, Alizadeh MH, Minoonejhad H, Razi M, Amraee GH. Predictor factors for lower extremity malalignment and non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(5):1625–31.

Pappas E, Shiyko MP, Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Biomechanical deficit profiles associated with ACL injury risk in female athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(1):107–13.

Nilstad A, Andersen TE, Bahr R, Holme I, Steffen K. Risk factors for lower extremity injuries in elite female soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):940–8.

O'Kane JW, Tencer A, Neradilek M, Polissar N, Sabado L, Schiff MA. Is knee separation during a drop jump associated with lower extremity injury in adolescent female soccer players? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(2):318–23.

Raisanen AM, Pasanen K, Krosshaug T, Vasankari T, Kannus P, Heinonen A, Kujala UM, Avela J, Perttunen J, Parkkari J. Association between frontal plane knee control and lower extremity injuries: a prospective study on young team sport athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000311.

Dingenen B, Malfait B, Nijs S, Peers KH, Vereecken S, Verschueren SM, Staes FF. Can two-dimensional video analysis during single-leg drop vertical jumps help identify non-contact knee injury risk? A one-year prospective study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2015;30(8):781–7.

Leppanen M, Pasanen K, Kujala UM, Vasankari T, Kannus P, Ayramo S, Krosshaug T, Bahr R, Avela J, Perttunen J, et al. Stiff landings are associated with increased ACL injury risk in young female basketball and floorball players. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(2):386–93.

Numata H, Nakase J, Kitaoka K, Shima Y, Oshima T, Takata Y, Shimozaki K, Tsuchiya H. Two-dimensional motion analysis of dynamic knee valgus identifies female high school athletes at risk of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(2):442–7.

Goerger BM, Marshall SW, Beutler AI, Blackburn JT, Wilckens JH, Padua DA. Anterior cruciate ligament injury alters preinjury lower extremity biomechanics in the injured and uninjured leg: the JUMP-ACL study. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(3):188–95.

Smeets A, Malfait B, Dingenen B, Robinson MA, Vanrenterghem J, Peers K, Nijs S, Vereecken S, Staes F, Verschueren S. Is knee neuromuscular activity related to anterior cruciate ligament injury risk? A pilot study. Knee. 2019;26(1):40–51.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Markolf KL, Burchfield DM, Shapiro MM, Shepard MF, Finerman GA, Slauterbeck JL. Combined knee loading states that generate high anterior cruciate ligament forces. J Orthop Res. 1995;13(6):930–5.

Markolf KL, Gorek JF, Kabo JM, Shapiro MS. Direct measurement of resultant forces in the anterior cruciate ligament. An in vitro study performed with a new experimental technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(4):557–67.

Fukuda Y, Woo SL, Loh JC, Tsuda E, Tang P, McMahon PJ, Debski RE. A quantitative analysis of valgus torque on the ACL: a human cadaveric study. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(6):1107–12.

Ardern CL, Ekas G, Grindem H, Moksnes H, Anderson AF, Chotel F, Cohen M, Forssblad M, Ganley TJ, Feller JA, et al. 2018 International Olympic Committee consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis, and Management of Pediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(3):2325967118759953.

van Melick N, van Cingel RE, Brooijmans F, Neeter C, van Tienen T, Hullegie W, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(24):1506–15.

Prodromos CC, Han Y, Rogowski J, Joyce B, Shi K. A meta-analysis of the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender, sport, and a knee injury-reduction regimen. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(12):1320–1325 e1326.

Montalvo AM, Schneider DK, Yut L, Webster KE, Beynnon B, Kocher MS, Myer GD. “What's my risk of sustaining an ACL injury while playing sports?” A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(16):1003–12.

Fox AS, Bonacci J, McLean SG, Spittle M, Saunders N. What is normal? Female lower limb kinematic profiles during athletic tasks used to examine anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2014;44(6):815–32.

Olsen OE, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Injury mechanisms for anterior cruciate ligament injuries in team handball: a systematic video analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):1002–12.

Koga H, Nakamae A, Shima Y, Iwasa J, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Bahr R, Krosshaug T. Mechanisms for noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: knee joint kinematics in 10 injury situations from female team handball and basketball. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2218–25.

Krosshaug T, Nakamae A, Boden BP, Engebretsen L, Smith G, Slauterbeck JR, Hewett TE, Bahr R. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: video analysis of 39 cases. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(3):359–67.

Schilaty ND, Bates NA, Krych AJ, Hewett TE. Frontal plane loading characteristics of medial collateral ligament strain concurrent with anterior cruciate ligament failure. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(9):2143–50.

Ueno R, Navacchia A, Bates NA, Schilaty ND, Krych AJ, Hewett TE. Analysis of internal knee forces allows for the prediction of rupture events in a clinically relevant model of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(1):2325967119893758.

Zhang L, Hacke JD, Garrett WE, Liu H, Yu B. Bone bruises associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury as indicators of injury mechanism: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2019;49(3):453–62.

Schache AG, Baker R, Lamoreux LW. Defining the knee joint flexion-extension axis for purposes of quantitative gait analysis: an evaluation of methods. Gait Posture. 2006;24(1):100–9.

Robinson MA, Donnelly CJ, Tsao J, Vanrenterghem J. Impact of knee modeling approach on indicators and classification of anterior cruciate ligament injury risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(7):1269–76.

Fantozzi S, Stagni R, Cappello A, Leardini A. Effect of different inertial parameter sets on joint moment calculation during stair ascending and descending. Med Eng Phys. 2005;27(6):537–41.

Leardini A, Chiari L, Della Croce U, Cappozzo A. Human movement analysis using stereophotogrammetry. Part 3. Soft tissue artifact assessment and compensation. Gait Posture. 2005;21(2):212–25.

Mok KM, Petushek E, Krosshaug T. Reliability of knee biomechanics during a vertical drop jump in elite female athletes. Gait Posture. 2016;46:173–8.

Gwynne CR, Curran SA. Quantifying frontal plane knee motion during single limb squats: reliability and validity of 2-dimensional measures. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(7):898–906.

McLean SG, Walker K, Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE, van den Bogert AJ. Evaluation of a two dimensional analysis method as a screening and evaluation tool for anterior cruciate ligament injury. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(6):355–62.

Sorenson B, Kernozek TW, Willson JD, Ragan R, Hove J. Two- and three-dimensional relationships between knee and hip kinematic motion analysis: single-leg drop-jump landings. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24(4):363–72.

Thorlund K, Imberger G, Walsh M, Chu R, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Guyatt G, Devereaux PJ, Thabane L. The number of patients and events required to limit the risk of overestimation of intervention effects in meta-analysis--a simulation study. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25491.

Atkin K, Herrington L, Alenezi F, Jones P, Jones R. The relationship between 2D knee valgus angle during single leg squat (SLS), single leg landing (SLL), and forward running. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):563.

Donohue MR, Ellis SM, Heinbaugh EM, Stephenson ML, Zhu Q, Dai B. Differences and correlations in knee and hip mechanics during single-leg landing, single-leg squat, double-leg landing, and double-leg squat tasks. Res Sports Med. 2015;23(4):394–411.

von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:35.

Bates NA, Schilaty ND, Nagelli CV, Krych AJ, Hewett TE. Multiplanar loading of the knee and its influence on anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament strain during simulated landings and noncontact tears. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(8):1844–53.

Quatman CE, Quatman-Yates CC, Hewett TE. A ‘plane’ explanation of anterior cruciate ligament injury mechanisms: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2010;40(9):729–46.

Kiapour AM, Demetropoulos CK, Kiapour A, Quatman CE, Wordeman SC, Goel VK, Hewett TE. Strain response of the anterior cruciate ligament to uniplanar and multiplanar loads during simulated landings: implications for injury mechanism. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(8):2087–96.

Navacchia A, Bates NA, Schilaty ND, Krych AJ, Hewett TE. Knee abduction and internal rotation moments increase ACL force during landing through the posterior slope of the tibia. J Orthop Res. 2019;37(8):1730–42.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by the faculty of medicine at Lund University, Sweden. Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to the acquisition of data, was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data and was in charge of writing the manuscript. EA contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to the acquisition of data, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and contributed to the drafts of this paper. MWC, contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and contributed to the drafts of this paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors state that they have no competing interests relevant to the content of this review.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cronström, A., Creaby, M.W. & Ageberg, E. Do knee abduction kinematics and kinetics predict future anterior cruciate ligament injury risk? A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21, 563 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03552-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03552-3