Abstract

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the most common joint replacement surgery in Canada. Earlier Canadian work reported 1 in 5 TKA patients expressing dissatisfaction following surgery. A better understanding of satisfaction could guide program improvement. We investigated patient satisfaction post-TKA in British Columbia (BC).

Methods

A cohort of 515 adult TKA patients was recruited from across BC. Survey data were collected preoperatively and at 6 and 12 months, supplemented by administrative health data. The primary outcome measure was patient satisfaction with outcomes. Potential satisfaction drivers included demographics, patient-reported health, quality of life, social support, comorbidities, and insurance status. Multivariable growth modeling was used to predict satisfaction at 6 months and change in satisfaction (6 to 12 months).

Results

We found dissatisfaction rates (“very dissatisfied”, “dissatisfied” or “neutral”) of 15% (6 months) and 16% (12 months). Across all health measures, improvements were seen post-surgery. The multivariable model suggests satisfaction at 6 months is predicted by: pre-operative pain, mental health and physical health (odds ratios (ORs) 2.65, 3.25 and 3.16), and change in pain level, baseline to 6 months (OR 2.31). Also, improvements in pain, mental health and physical health from 6 to 12 months predicted improvements in satisfaction (ORs 1.24, 1.30 and 1.55).

Conclusions

TKA is an effective intervention for many patients and most report high levels of satisfaction. However, if the TKA does not deliver improvements in pain and physical health, we see a less satisfied patient. In addition, dissatisfied TKA patients typically see limited improvements in mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the most commonly performed joint replacement surgery in Canada where there were over 67,000 TKAs in 2016/17 [1]. TKA is typically performed on people with osteoarthritis, the prevalence of which increases with age, and so demand for TKA can be expected to continue to rise given population demographic trends [2,3,4]. Through 2015/16, Canada saw a 5-year increase in TKA procedures of 16% [1]. A commonly cited and troubling statistic is that approximately 1 in 5 TKA patients express some dissatisfaction with their outcomes following surgery [5, 6]. The concern is magnified when placed in the contemporary context of health system commitments to patient-centred care, with consideration of traditionally ignored outcomes such as patient satisfaction and quality of life [7, 8]. Using a patient-centred lens, a dissatisfied TKA patient has not had a successful surgery, and a rate of 20% dissatisfied patients points to a need for improvement. A better understanding of patient satisfaction drivers could guide program improvement initiatives.

Previous studies have explored the relationship between post-TKA patient satisfaction and various combinations of pre- and post-surgery clinical and patient-reported measures. Factors found to be related to patient dissatisfaction across multiple studies include: knee-related factors (e.g., pain, functioning, stiffness and inflammation), self-rated factors (e.g., physical and mental health status, and quality of life), pre-surgery expectations not met, complications, pain catastrophizing, and patient demographics (e.g., age, gender and employment status) [5, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The existing literature typically reports analyses of post-TKA patient satisfaction at a single time, even if repeated measurements (most commonly at 6- and 12-months) were made, and so contributes very little to understanding changes in satisfaction over time [20,21,22,23]. For example, are the concerns of patients in the early post-operative period different from those dealing with longer-term dissatisfaction? That requires a longitudinal analysis which simultaneously adjusts for correlations between repeated measures [24].

The longitudinal observational study reported in this paper was designed to understand patient satisfaction with TKA at 6 and 12-months post-surgery, as well as changes in satisfaction over time. The paper reports the quantitative work from a multiphase, longitudinal, mixed methods study investigating patient satisfaction following TKA surgery [25]. Using a patient-centred perspective, we investigated patient satisfaction rates post-TKA in British Columbia (BC), with exploration of the primary drivers of variation in the level of, and change in, patient satisfaction following TKA.

Methods

Setting, sample and data collection

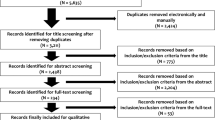

A cohort of 515 patients was recruited from six hospital sites spanning all regional health authorities in BC. Consecutive patients (aged 19 years or older) with a primary or secondary diagnosis of osteoarthritis, and scheduled to undergo primary TKA at one of the six sites, were invited to participate during mandatory pre-surgical total joint replacement education sessions. Patients scheduled to undergo revision surgery, bilateral knee replacement, unicompartmental knee replacement, or TKA due to an accident were excluded. The participation rate was 57% (515/808) out of all invited patients. Approval was obtained from research ethics boards of all health authorities and universities in the study.

Much of the study data were collected using a preoperative survey questionnaire (administered up to 3 months before surgery) and two post-operative survey questionnaires (at 6 and 12 months post-surgery). The questionnaires were self-administered in English, with family members or caregivers serving as translators for non-English speaking patients. All non-respondents received reminders. Retention rates were 91% (466/515) and 88% (455/515) at 6 and 12 months, respectively. In addition, health administrative data were obtained from medical records of consenting patients (93%, 479/515).

Measurements and outcomes

The primary outcome measure was patient satisfaction with the results of their knee surgery, collected at 6 and 12 months. These intervals were chosen to mirror previous work in TKA [5], and endorsed by clinical experts on our team. Participants were asked to respond to a single-item measuring satisfaction with the outcomes of knee surgery based on a 5-point Likert rating (varying from “very satisfied” through “very dissatisfied”), which was previously used in a large Canadian cohort study of knee arthroplasty outcomes [4]. For analysis purposes, the primary satisfaction outcome variable was collapsed into a binary variable with values 0 (“very satisfied” or “satisfied”) and 1 (“very dissatisfied”, “dissatisfied” or “neutral”).

Potential patient-centred drivers of satisfaction explored in our analyses, based on the literature review, included demographic variables, patient-reported health status (SF-12 [26], EQ-5D-5 L [27], WOMAC [28], SLANSS [29]), depression and anxiety (HADS [30]), social support (MOS-SSS [31]), patient expectations, comorbidities (Charlson [32]), health insurance, and global quality of life (Cantril [33]). All selected instruments have been used previously in TKA patients, with strong evidence for their validity [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

In addition to patient-reported measures, administrative data were extracted from in-patient medical records to measure hospital length of stay during the surgical period, complications following surgery, re-admissions and presence of co-morbidity during the inpatient stay. The patient’s postal code information was used to classify rural/urban residence and to measure distances from the patient’s home to the hospital where they had their TKA surgery, and the nearest hospital where TKA is offered.

Analyses

Multivariable growth modeling was conducted using the MPlus software (version 7.4) [34] to predict individual differences in satisfaction at 6 months (intercepts) and change (slopes) in satisfaction from 6 to 12 months [35, 36]. The model was specified as a logistic regression, with satisfaction as a binary variable and random effects for the intercepts and slopes. Accordingly, the results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) pertaining to the intercepts and slopes associated with the independent variables. To minimize collinearity issues resulting from high correlations over time, the time-varying predictor variables were represented as pre-surgery scores, the change from pre-surgery to 6 months post-surgery, and the change from 6 to 12 months post-surgery. All continuous predictor variables were rescaled to vary from 0 to 10 to enhance interpretability and comparisons for the odds ratios. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was applied to accommodate for missing data.

The model was built sequentially where the selection of variables was informed by prior studies, findings from our qualitative analysis [37], and emerging statistical results, including changes in overall model fit and parameter estimates [38, 39]. First, the patient-reported outcome variables (WOMAC subscales, SF-12 mental and physical health component scores, the EQ-5D valuation score) were examined. To avoid multicollinearity, variable selection at this step was guided by identifying a set of variables that were correlated with satisfaction and least correlated with one another. Second, demographic variables (age, sex, health region, marital status, education, ethnicity, and urban versus rural) were entered into the model. The third and final step involved examining other health-related predictors, including neuropathic pain (SLANSS), depression and anxiety (HADS), social support (MOS SSS), comorbidities (Charlson), health insurance, and global quality of life (Cantril). At each of steps 2 and 3, all variables were first entered simultaneously and the models were subsequently trimmed by sequentially removing variables that were not statistically significant predictors (p < .05) while monitoring the impact on overall model fit, based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and changes in parameter estimates.

Results

The characteristics of the patient cohort at the time of recruitment into the study are reported in Table 1. The cohort had a mean age of 66 years, was predominantly female (61%), over one-quarter was still working and over half waited longer than 12 months for surgery. Almost one-third of patients had no supplementary health insurance to cover the costs of additional health care services such as privately-financed physiotherapy over and above the standard series of publicly provided physiotherapy.

Table 2 reports the results of the primary outcome variable, satisfaction with outcomes (at both 6 and 12 months post-surgery). Our data indicate an overall dissatisfaction rate (“very dissatisfied”, “dissatisfied” or “neutral”) of 15% at 6 months and 16% at 12 months post-surgery. The vast majority of participants (78%) were satisfied or very satisfied with their outcomes at both time points, and 8% indicating some level of dissatisfaction (or neutrality) at both time points.

Self-reported patient health outcomes over time are reported in Table 3. Our data point to major improvements in patient health post-surgery; a finding seen across all outcome instruments. The improvement is most clearly seen from baseline to 6 months, with very little further improvement beyond 6 months. Improvements were seen in quality of life, pain, physical function and mental health.

The final multivariable model predictors of satisfaction are shown in Table 4. This represents the best fitting and most parsimonious model predicting satisfaction and change in satisfaction scores. The multilevel multivariable regression results suggest that self-reported pre-operative pain, based on the WOMAC, as well as the difference in pain at 6 months were predictive of satisfaction at 6 months. In addition, pre-operative mental and physical health are both predictive of satisfaction at 6 months (ORs 3.25 and 3.16, respectively). Change in pain from 0 to 6 months was also predictive of satisfaction at 6 months (OR = 2.31). However, changes in mental and physical health from 0 to 6 months were not. Further, a change in any of the three variables (pain, mental health and physical health) from 6 to 12 months was predictive of a change in satisfaction; people experiencing improved pain, mental health or physical health were more likely also to experience improved satisfaction from 6 to 12 months (ORs 1.30, 1.55 and 1.24, respectively).

Different combinations of the core patient-reported outcome variables (including the SF-36 component scores, the WOMAC subscales, and EQ-5D) were explored, but none resulted in additional statistically significant parameter estimates and improved model fit (based on the BIC). The addition of individual time-invariant variables (marital status, age, gender, comorbidity, and having additional health insurance) also did not result in any improvement in model fit, regardless of whether the variables were entered individually or in combination with one or more other time-invariant variables. Model fit was also not improved by any of the other patient-reported outcome variables (global quality of life, neuropathic pain, anxiety, depression and social support) when entered into the model as pre-operative scores and their difference scores at 6 and 12 months.

In summary, a key driver of patient satisfaction post-surgery is pain (both pre-surgery and the change in pain levels over time). The other factors associated with patient satisfaction post-surgery are both physical health (over and above pain) and mental health. Many other factors were found not to have an association with patient satisfaction, notably socio-demographic characteristics of patients, patient expectations and level of support.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Our data indicate that TKA is an effective intervention for many recipients, with major gains in health-related quality of life reported by those who receive the procedure. Further, most patients report high levels of satisfaction post-surgery: we found an overall dissatisfaction rate among Canadian TKA patients of approximately 16% at 12 months post-surgery. Although this dissatisfaction rate, in aggregate, remains stable from 6 to 12 months post-surgery, we do see movement over time; some patients indicating increasing dissatisfaction and others moving in the opposite direction. When looking to understand factors associated with patient satisfaction, the longitudinal nature of our data and analyses allow us to tease out the impact of pre-surgery measurements and changes over time. Our results indicate three key satisfaction drivers: pain, physical health and mental health. Pre-surgery levels of all three variables were found to be important predictors of satisfaction at 6 months; and changes in the levels of all three (from 6 to 12 months post-surgery) were strongly associated with changes in satisfaction. In summary, if the TKA procedure has positive impacts on a patient’s pain levels and overall physical health, we are likely to see a satisfied patient. However, and more surprisingly, we also see that satisfied TKA patients are also likely to have seen some improvements in relation to mental health too.

Comparison with previous work

Our study resembles others in finding knee pain to be a key predictor of post-TKA satisfaction [13, 16, 40, 41]. This common finding holds for both pre-surgical pain and post-surgery pain improvement. Our study also reinforces findings by others that pre-surgical physical and mental health are positively related to post-TKA patient satisfaction [13, 16, 19, 41, 42]. However, given our longitudinal analysis, our study departs from the existing literature in being able to comment on contributors to change in satisfaction rates over time. As far as we know, our principal findings of a relationship between changes in pain, physical health status and mental health status and changes in patient satisfaction have not been shown previously.

Strengths and weaknesses of our study

One of the main strengths of our research is the longitudinal design and analysis of the research. Ours is not the first study of knee replacement experience to measure satisfaction longitudinally, but it is the first to employ methods that directly incorporate the longitudinal data into the analysis. Another major strength is the retention rates achieved; approximately 90% of the cohort returned surveys at both 6 and 12 months, with very little loss over time. However, we also recognize that many patients invited to participate in this research chose not to do so, the consequence being a challenge to the representativeness of the sample.

The limited ethnic diversity in our sample is a weakness, resulting in part from the fact that we were able only to use English language surveys and study materials. Further work is required to establish the generalizability of our findings to other major ethnic groups in British Columbia and Canada more generally. We selected a measure of patient satisfaction used previously in a Canadian TKA context, in part to facilitate direct comparison with earlier Canadian work [5]. We do, however, acknowledge weaknesses with the satisfaction measure, notably its focus on satisfaction with results only, as opposed to a broader measure of patient experience. Our sample of patients all received care in BC, with recruitment from all regions of the province, reflecting both urban and more rural settings. To facilitate the recruitment process, we targeted pre-surgery education sessions and so we were only able to recruit from hospital sites that offered such education. Finally, other variables not measured in this study may explain some variation in satisfaction. For example, we had data on supplementary health insurance status but not on which patients might have augmented the standard series of publicly-provided physiotherapy with additional privately-financed physiotherapy or on the total number of private physiotherapy sessions received. We would encourage future research on this topic to consider gathering additional clinical data (e.g., clinical indication for surgery such as pain or joint surface destruction; clinical outcomes such as knee alignment; services provided such as number of physiotherapy sessions, and patient out of pocket costs) that might point directly to actions for improvement.

Conclusions

Our research confirms the importance of pain and functioning post-surgery as key drivers of patient satisfaction. Ongoing monitoring of such patient-reported factors, and intervention in cases where such symptoms persist, is central to patient satisfaction. Another key finding of our work is that a patient’s mental health also heavily influences satisfaction post-TKA. Both the level of self-reported mental health and changes in that level over time predict satisfaction rates. This important finding points to the need for broad clinical review of patients, before and after surgery that encompasses both physical and mental health aspects. Screening for and addressing mental health concerns will likely be a new domain for many surgical orthopedic programs. The priority research implications of this work are two-fold. First, we need to explore the robustness of our results across more ethnically diverse British Columbian and Canadian patient populations. Second, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of any new interventions targeting the drivers of dissatisfaction uncovered in our work will need to be tested empirically. For example, a response to our findings might be to consider new interventions to promote mental health and wellness amongst patients receiving TKA but this should, of course, be subjected to evaluation of its costs and benefits before implementation.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- CIHI:

-

Canadian Institutes for Health Information

- EQ-5D-5 L:

-

Euroqol 5 dimension, 5 level instrument

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- MOS-SSS:

-

Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SF-12:

-

Short-form 12 instrument

- SLANSS:

-

Self-completed Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs pain scale

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Hip and Knee Replacements in Canada, 2016-2017: Canadian joint replacement registry annual report. Ottawa: CIHI; 2018 [Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-joint-replacement-registry-cjrr].

Mahomed NN, Barrett J, Katz JN, Baron JA, Wright J, Losina E. Epidemiology of total knee replacement in the United States Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1222–8.

Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Sayre EC, Cibere J, Flanagan WM, Aghajanian J, et al. Trends in physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis incidence an an administrative database in British Columbia, Canada, 1996-1997 through 2003-2004. Arthrit Rheum-Arthr. 2008;59(7):929–34.

Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot JM, Le Petit C, Aghajanian J, Sayre EC, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia. Canada J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):386–93.

Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57–63.

Gandhi R, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Predicting patient dissatisfaction following joint replacement surgery. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(12):2415–8.

Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1275–85.

Association OM. Patient-Centred care. Ontario: OMA; 2010.

Barlow T, Clark T, Dunbar M, Metcalfe A, Griffin D. The effect of expectation on satisfaction in total knee replacements: a systematic review. Springerplus. 2016;5:167.

Choi Y-J, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after Total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surgery & Related Research. 2016;28(1):15.

Culliton SE, Bryant DM, Overend TJ, MacDonald SJ, Chesworth BM. The relationship between expectations and satisfaction in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2012;27(3):490–2.

Dunbar MJ, Haddad FS. Patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: new inroads. Bone Joint J. 2014;96 - B(10):1285–6.

Gibon E, Goodman MJ, Goodman SB. Patient satisfaction after Total knee arthroplasty: a realistic or imaginary goal? Orthop Clin North Am. 2017;48(4):421–31.

Hamilton DF, Lane JV, Gaston P, Patton JT, Macdonald D, Simpson AH, et al. What determines patient satisfaction with surgery? A prospective cohort study of 4709 patients following total joint replacement. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):e002525.

Jones CA, Beaupre LA, Johnston DW, Suarez-Almazor ME. Total joint arthroplasties: current concepts of patient outcomes after surgery. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2007;33(1):71–86.

Lau RL, Gandhi R, Mahomed S, Mahomed N. Patient satisfaction after total knee and hip arthroplasty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(3):349–65.

Nam D, Nunley RM, Barrack RL. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a growing concern? Bone Joint J. 2014;96 - B(11 Supple A):96–100.

Schulze A, Scharf HP. Satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Comparison of 1990-1999 with 2000-2012. Orthopade. 2013;42(10):858–65.

Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, Busschbach JJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M. Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(4):576–88.

Adie S, Dao A, Harris IA, Naylor JM, Mittal R. Satisfaction with joint replacement in public versus private hospitals: a cohort study. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82(9):616–24.

Dickstein R, Heffes Y, Shabtai EI, Markowitz E. Total knee arthroplasty in the elderly: patients’ self-appraisal 6 and 12 months postoperatively. Gerontology. 1998;44(4):204–10.

Harris IA, Harris AM, Naylor JM, Adie S, Mittal R, Dao AT. Discordance between patient and surgeon satisfaction after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(5):722–7.

Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM. Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1):55–61.

Verbeke G, Fieuws S, Molenberghs G, Davidian M. The analysis of multivariate longitudinal data: a review. Stat Methods Med Res. 2014;23(1):17.

Leech N, Onwuegbuzie A. A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual Quant. 2007;43(2):10.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72.

McConnell S, Kolopack P, Davis AM. The Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC): a review of its utility and measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(5):453–61.

Bennett MI, Smith BH, Torrance N, Potter J. The S-LANSS score for identifying pain of predominantly neuropathic origin: validation for use in clinical and postal research. J Pain. 2005;6(3):149–58.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Cantril H. The Pattern of Human Concerns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1965.

Muthén B, Muthén L. MPlus (version 7.4). Statmodel: Los Angeles; 2015.

Heck RH, Thomas SL. An introduction to multilevel modeling techniques : MLM and SEM approaches using Mplus. 3rd ed. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York; 2015.

Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P. Intensive longitudinal methods : an introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. p. 256.

Goldsmith LJ, Suryaprakash N, Randall E, Shum J, MacDonald V, Sawatzky R, et al. The importance of informational, clinical and personal support in patient experience with total knee replacement: a qualitative investigation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):127.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

Wu W, West SG, Taylor AB. Evaluating model fit for growth curve models: integration of fit indices from SEM and MLM frameworks. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(3):183–201.

Dunbar MJ, Richardson G, Robertsson O. I can't get no satisfaction after my total knee replacement: rhymes and reasons. Bone Joint J. 2013;95 - B(11 Suppl A):148–52.

Husain A, Lee GC. Establishing realistic patient expectations following Total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(12):707–13.

Khatib Y, Madan A, Naylor JM, Harris IA. Do psychological factors predict poor outcome in patients undergoing TKA? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(8):2630–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the TKA patients who participated in this research study, and acknowledge the data collection contributions from Jessica Shum, Faith Furlong, Heidi Howay, Christine Morrison, Valerie Oglov and Christina Parkin. Study guidance was provided by our collaborators and advisory team members, including Ramin Mehin, Susann Camus, Susan Chunick, Alison Dormuth, Denise Dunton, Vivian Giglio, Charlie Goldsmith, David Nelson, Cindy Roberts, Magdelena Newman, Joan Vyner, Mike Wasdell, Robert Bourne, and many others.

Funding

The study “Why are so many patients dissatisfied with knee replacement surgery? Exploring variations of the patient experience” was funded through support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Partnerships for Health System Improvement (CIHR PHSI) operating grant (number 114106), the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR; number PJ HSP 00004 [10–1]), and the BC Rural & Remote Health Research Network. Funding and in-kind support were received from Vancouver Coastal Health Authority and Fraser Health Authority. Dr. Sawatzky holds a Canada Research Chair (CRC) in Patient-Reported Outcomes from the Government of Canada CRC program. Dr. Davis held postdoctoral funding from CIHR and MSFHR during this study. Assistance with the pre-funding study design was provided through in-kind support from the Fraser Health Authority. Otherwise, no funder of this study was involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Request for access to study data should be directed to the corresponding author (SB). This study has approval for secondary data analysis but any release of data to other parties will require a new ethics approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB led and participated in the design, conduct and analysis of this study and the drafting of this manuscript. RS and LJG participated in the design, conduct and analysis of the study and helped draft the manuscript. JD, SH, VM, PM, ER, NS, and AW participated in the design, conduct and analysis of the study and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SB also led the overall mixed methods study within which this quantitative study was embedded. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from relevant universities and health regions: University of British Columbia, reference number H11–02117; Simon Fraser University, reference number 2012 s0142; Trinity Western University 12 F02; Fraser Health Authority 2011–087, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority V11–02117; Vancouver Island Health Authority C2012–043; Interior Health Authority 2012–13–010–E; and Northern Health Authority RRC–2012–0019. All study participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in this study.

Consent for publication

All study participants provided written informed consent for the information collected to be used for publication where no information that disclosed their identity was released or published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bryan, S., Goldsmith, L.J., Davis, J.C. et al. Revisiting patient satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19, 423 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2340-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2340-z