Abstract

Background

Deltoid ligament (DL) rupture is commonly seen in clinical practice; however the need to explore and surgically repair it is still in debate. The objective of the current study is to compare the outcomes of surgical treatment of ankle fracture with or without DL repair.

Methods

Between 2009 and 2015, Seventy-four ankle fractures with DL rupture were identified and followed. Twenty patients were treated with surgical repair of the DL, while 54 were not. The pre- and post-operative medial clear space (MCS) were measured and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) ankle-hindfoot score and visual analogue scale (VAS) were used for functional evaluation. According to the radiological malreduction of MCS, the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each potential relative factor were calculated.

Results

The mean followup time was 53.7 months. The mean MCS preoperatively, postoperatively, and at last followup time were 8.7 ± 2.4 (range, 6.2–14.8) mm, 3.7 ± 0.9 (range, 2.6–6.4) mm, 3.6 ± 1.0 (range, 2.6–6.8) mm, respectively. The mean AOFAS score was 86.4 ± 8.1 (range, 52–100) points, and the mean VAS was 1.4 ± 1.4 (range, 0–7) points. During followup, 14.9% (11/74) cases were found to be malreduced (MCS>5 mm), and 5.4% (4/74) went on to failure. Surgical repair of DL can significantly decrease the postoperative MCS (P<0.05), and can also decrease the malreduction rate (P<0.05). AO/OTA type-C ankle fractures showed a positive correlation with malreduction (OR = 4.38, P = 0.03). In this type of injury, surgical repair of the DL can significantly decrease the malreduction rate (P<0.05). No significant difference was found between the AO/OTA type-B fracture with or without DL repair.

Conclusions

Surgical repair of the DL is helpful in decreasing the postoperative MCS and malreduction rate, especially for the AO/OTA type-C ankle fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The deltoid ligament (DL) rupture is highly relevant in clinical practice where ankle injuries are commonly encountered [1,2,3,4]. An arthroscopic study reported a partial or total rupture of the deltoid ligament in 39.6% of ankle fracture patients [5]. Another magnetic resonance imaging investigation reported 58.3% of acute ankle fractures have been found with tears of the deltoid ligament [4]. However, in ankle fractures combined with DL rupture, the necessity of surgical repair of the deltoid ligament is always in debate.

Early studies suggested that exploration of the medial side of the ankle and repair of the deltoid ligament were not necessary after anatomical reduction and rigid internal fixation of the lateral malleolus [6,7,8,9]. A prospective randomized study reported no difference in early mobilization or in long term results between deltoid ligament repaired and unrepaired groups [9]. However, another study reported that unrepaired deltoid ligament may be a source of persistent pain or pronation deformity when not appropriately treated [10]. Johnson and Hill [11] reported 30 patients with combined fibular fracture and deltoid ligament rupture, where the fibula was fixed and the deltoid ligament was left unrepaired, and the results showed poor symptomatic and functional result in 41% of patients. Until now, the dilemma of whether the deltoid ligament should be surgically repaired in acute ankle fracture is still controversial. Thus, we retrospectively studied the ankle fracture patients with DL rupture in our center to evaluate the need for surgical repair of the deltoid ligament.

Methods

The current study was approved by the research board in our hospital. The authors retrospectively studied the clinical and radiological outcomes of operative treatment of ankle fractures with DL rupture between March 2009 and December 2015. The inclusion criteria contained: (1) adults greater than 18 years old; (2) with acute closed ankle fractures treated operatively; (3) with preoperative medial clear space (MCS) ≥ 6 mm in anterior-posterior ankle X-rays; (4) and at least 12 months followup. The exclusion criteria contained: (1) the time of injury to surgical intervention more than 14 days; (2) open ankle fractures; (3) DL rupture combined with medial malleolar fracture; (4) pathological fractures; (5) with preoperative dysfunction of the lower limb.

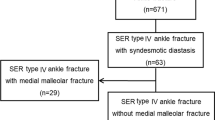

A total of 2432 ankle fractures treated operatively were identified initially. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, seventy-four patients with 52 males and 22 females were included in current study (Fig. 1). The average age was 39.5 ± 15.5 (range, 18–76) years. Causes of fracture included 42 sprains, 13 falls from height, 12 traffic injuries and 7 sports injuries. According to the AO/OTA classification system [12], 49 type-B and 25 type-C were included; according to Lauge-Hansen classification system [13], there were 49 supination-external rotation (SER), 19 pronation-external rotation (PER) and 6 pronation-abduction (PA) injuries. The preoperative MCS was 8.7 ± 2.4 (range, 6.2–14.8) mm. Twenty patients were treated with surgical repair of DL, and 54 patients were not. The basic information in two groups was similar (Table 1).

All patients were treated with a similar surgical protocol. For the AO/OTA type-B fracture, the fibular length and rotation was restored, and fixed with a small-fragment plate and screws. The posterior malleolar fracture was reduced and fixed for fragments larger than 10% of the articular surface based on the lateral X-ray. If the syndesmotic complex was disrupted, as indicated by its widening during operation, one or two screws were placed across it. For the AO/OTA type-C fracture, the fibula fracture was openly reduced and fixed if it involved the distal two-thirds fragment, but most of the proximal one third fibula fractures were left without fixation after the length and rotation were restored and syndesmotic screws were placed. The posterior malleolar fracture was treated similar to the AO/OTA type-B fracture. For the patients who underwent repair of the DL, reinsertion to the medial malleolus or talus was achieved by suturing directly to the bone, and enhanced with a suture anchor (Fig. 2). The superficial component ruptures were sutured with absorbable suture.

a The preoperative X-ray showed enlargement of the medial clear space. b MRI revealed the totally rupture of the deep layer of deltoid ligament (arrow). c The postoperative X-ray showed good reduction of the medial clear space. d Intraoperative photo showed rupture of the deltoid ligament (arrow). e A suture anchor was placed in the talus insertion of the deep layer of deltoid ligament (arrow). (f and g) The deep (arrow) and superficial layers were sutured

Postoperatively, all patients were immobilized in a short leg cast. At 6 weeks, the cast was taken off, followed by aggressive range of motion and strengthening exercises. The syndesmosis screw was removed in 8 to 12 weeks before full weight-bearing.

Clinical and radiographic examination

The preoperative, postoperative and final followup anterior-posterior ankle joint X-rays were analyzed. The MCS was measured with Harper’s method [7]. The MCS ≥ 5 mm at any postoperative followup time was defined as malreduction. Treatment failure was defined as symptomatic malreduction and need for any revision surgery.

The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) ankle-hindfoot score and visual analogue scale (VAS) was used for functional evaluation at the final followup time [11]. For the failure cases, the AOFAS and VAS scores before revision were included as the final outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis of the included data was performed using Student t test or Pearson chi-square test with the level of significance set at α = 0.05. According to the malreduction rate, odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for the potential relative factor. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

The mean followup time was 53.7 ± 23.8 (range, 14–97) months. The mean AOFAS at followup time was 86.4 ± 8.1 (range, 52–100) points; and the mean VAS was 1.4 ± 1.4 (range, 0–7) points. The mean postoperative MCS was 3.7 ± 0.9 (range, 2.6–6.4) mm, which was significantly decreased from the preoperative value (P<0.01), and maintained at the last followup time (3.6 ± 1.0 (range, 2.6–6.8) mm).

No malreduction or failures occurred in the DL repair group, however, the malreduction rate was 20.4% in unrepair group (P = 0.03). The failure rate was 7.4% in the unrepair group, but no significant difference was detected with the numbers available. According to the current study, the mean postoperative MCS was significantly smaller in the DL repair group (P = 0.03), and also smaller at the followup time (P = 0.03, Table 1). This may be because of the higher malreduced rate in the unrepair group. If the malreducted patients were excluded, the mean MCS decreased to 3.3 ± 0.4 mm postoperatively and 3.2 ± 0.4 mm at final followup time; and the difference disappeared when compared with repair group. No significant difference was detected for AOFAS and VAS scores with the numbers available.

The characteristics of the malreduced patients were summarized in Table 2. Four patients were considered failures and were revised 4–16 months after the initial operation. The other 7 patients all reached good functional outcomes, and painless walking although with increased MCS. The mean AOFAS score of the other 7 patients was 86.6 ± 3.3 (range, 85–95) points, and with a mean VAS score of 1.6 ± 1.1 (range, 0–3) points with a mean follow-up time of 62.6 months. According to our current results, OTA type-C injury was positively correlated with malreduction (Table 3). No correlation was found between malreduction and treatment methods. When compared to the functional outcomes with respect to the OTA classification, the malreduction rate in unrepaired Type-C patients was significantly higher than in unrepaired Type-B patients and repaired Type-C patients (Table 4).

Discussion

DL is a complex ligament structure spanning from the medial malleolus to the navicular, talus, and calcaneus bones, and it plays a role in limiting the anterior and posterior translation of the talus and restrains talar abduction. DL repair is performed more frequently than expected, particularly in Weber type B fractures [5]. Surgical treatment of intraarticular fractures is well-accepted as malreduction of the articular surface may cause post-traumatic osteoarthritis rapidly. However, the need for surgical repair of the ruptured DL after the anatomic reduction of the bony structures is still under debate.

Early studies showed that reconstruction of a ruptured DL was not necessary. Harper [7] reported 36 patients, all without repair of DL, and the results show no morbidity or evidence of ligamentous instability. Stromsoe et al. [9] reported a prospective randomized study including 50 patients, where the results showed no difference was found between groups. Baird et al. [6] reported 24 ankle fracture patients with DL rupture, with 21 patients without repair of the DL reaching a good to excellent rate of 90%; however, of the 3 patients with DL repair, 2 had poor results. So, the author concluded that exploration of the medial side of the ankle and repair of the DL are not necessary unless reduction of the lateral malleolus fails to reduce the talus within the ankle mortise. However, Zeegers and van der Werken [8] reported 28 patients without repair of the DL, and 8 (28.6%) had poor results. Johnson and Hill [11] reported 30 patients with combined fibula fracture and DL rupture, where the fibula was fixed and DL was left unrepaired, and the results showed poor symptomatic and functional result in 41% of patients. Tejwani et al. [14] reported that the functional outcome for those with a bimalleolar fracture is worse than that for those with a lateral malleolar fracture and disruption of the DL. In our current study, the functional outcomes between the DL repaired and unrepaired patients reached no significant difference with the numbers available. However, the malreduction rate was significantly higher in DL unrepaired group (0% versus 20.4%). And, in the malreducted patients, 36% (4/11) failed and required revision; although the other 64% (7/11) with increased posterior MCS reached good functional outcomes with a mean 5 years followup.

For the Weber type-B (SER-4) ankle fracture with DL rupture combined with syndesmosis instability, the use of a syndesmosis screw for temporary fixation was showed to increase the functional outcomes while without DL repair [15]. In our current study, we included 49 Weber type-B patients with DL rupture, and 17 with syndesmosis fixation, and 1 (5.9%) with malreduction of medial malleolar space but with good functional outcomes and without pain. According to our current results, the functional outcomes and radiological outcomes for the Weber type-B patients with DL rupture reached no significant difference with or without DL repair (Table 4). The Weber type-C fractures showed a positive correlation with malreduction in our current study (OR = 5.53, Table 3). However, if the DL was repaired, the malreduction rate decreased significantly even in Weber type-C fracture patients (P = 0.04). Lee et al. [16] reported that in the case of high-grade unstable fractures of the lateral malleolus, repair of the anterior DL was adequate for restoring medial stability. We do agree with Hintermann et al. [10] that careful reconstruction of the medial ligaments of the ankle is needed if restoration of full mechanical stability is not proven after internal fixation of Weber type-C ankle fracture. Many authors agreed that after anatomical reconstruction of the lateral malleolus with congruity of the ankle mortise there is no need to explore and repair the ruptured DL [7, 8, 17]. According to our current results, for the Weber type-B ankle fractures, DL repair may be not a necessary procedure after anatomic reduction of the bony structures (Fig. 3, Table 4); however, not for the type-C fractures (Fig. 4, Table 4).

a The preoperative X-ray showed an AO/OTA type-B ankle fracture. b The patient was treated with open reduction and internal fixation of lateral and posterior malleolus, and the medial clear space was back to normal without surgical repair of the deltoid ligament. c Two years followup show good reduction of the medial clear space

Limitations of our current study included that we used MCS ≥ 6 mm in anterior-posterior ankle X-ray without stress or gravity-stress, which may have a lower sensitivity, although most authors used MCS ≥ 5 mm on the initial unstressed anterior-posterior X-ray to define the DL rupture [7, 18, 19]. Park et al. [19] showed that measurement of an MCS ≥ 5 mm on stress radiographs taken in dorsiflexion-external rotation yielded a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 61–100%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI, 89–100%) in cadaveric study. Schuberth et al. [20] reported at an MCS ≥ 5 mm, the false-positive rate for deltoid rupture diminished to 26.9%; and with an MCS ≥ 6 mm, the false-positive rate for deltoid rupture was only 7.7%. As expected, larger MCS thresholds usually resulted in higher specificity but lower sensitivity [21]. Our current method ensured a high specificity for diagnosis. The low sensitivity also explained why we have a smaller percentage of medial ligament injury (6.9%) compared with the previous reports (10–22.6%) [8, 14]. For the postoperative evaluation, we used MCS ≥ 5 mm to define the malreduction just in order to increase the sensitivity. The other limitation was our retrospective design, and not a randomized assignment of the groups. However, the baselines of the two groups were similar, and our results showed very useful information for clinical practice which have not been reported before.

Conclusions

According to the current study, we concluded that the surgical repair of the DL is helpful in decreasing the postoperative MCS and malreduction rate; especially for the Weber type C ankle fractures. However, the relationship between increased MCS and failure is still unclear. A lot of the patients with increased MCS in the current study still with satisfactory outcomes during long term followup. According to the results, well designed prospective comparative studies focus on the necessary for surgical repair of DL are still needed.

Abbreviations

- AOFAS:

-

American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DL:

-

Deltoid ligament

- MCS:

-

Medial clear space

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PA:

-

Pronation-abduction

- PER:

-

Pronation-external rotation

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SER:

-

Supination-external rotation

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Fallat L, Grimm DJ, Saracco JA. Sprained ankle syndrome: prevalence and analysis of 639 acute injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;37:280–5.

Stufkens SA, van den Bekerom MP, Knupp M, Hintermann B, van Dijk CN. The diagnosis and treatment of deltoid ligament lesions in supination-external rotation ankle fractures: a review. Strategies in trauma and limb reconstruction. 2012;7:73–85.

Yammine K. The morphology and prevalence of the deltoid complex ligament of the ankle. Foot Ankle Spec. 2017;10:55–62.

Jeong MS, Choi YS, Kim YJ, Kim JS, Young KW, Jung YY. Deltoid ligament in acute ankle injury: MR imaging analysis. Skelet Radiol. 2014;43:655–63.

Hintermann B, Regazzoni P, Lampert C, Stutz G, Gachter A. Arthroscopic findings in acute fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:345–51.

Baird RA, Jackson ST. Fractures of the distal part of the fibula with associated disruption of the deltoid ligament. Treatment without repair of the deltoid ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1346–52.

Harper MC. The deltoid ligament. An evaluation of need for surgical repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988:156–68.

Zeegers AV, van der Werken C. Rupture of the deltoid ligament in ankle fractures: should it be repaired? Injury. 1989;20:39–41.

Stromsoe K, Hoqevold HE, Skjeldal S, Alho A. The repair of a ruptured deltoid ligament is not necessary in ankle fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:920–1.

Hintermann B, Knupp M, Pagenstert GI. Deltoid ligament injuries: diagnosis and management. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:625–37.

Johnson DP, Hill J. Fracture-dislocation of the ankle with rupture of the deltoid ligament. Injury. 1988;19:59–61.

Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium - 2007: Orthopaedic trauma association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:S1–133.

Shariff SS, Nathwani DK. Lauge-Hansen classification--a literature review. Injury. 2006;37:888–90.

Tejwani NC, McLaurin TM, Walsh M, Bhadsavle S, Koval KJ, Egol KA. Are outcomes of bimalleolar fractures poorer than those of lateral malleolar fractures with medial ligamentous injury? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1438–41.

Ebraheim NA, Elgafy H, Padanilam T. Syndesmotic disruption in low fibular fractures associated with deltoid ligament injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003:260–7.

Lee TH, Jang KS, Choi GW, et al. The contribution of anterior deltoid ligament to ankle stability in isolated lateral malleolar fractures. Injury. 2016;47:1581–5.

Tornetta P 3rd. Competence of the deltoid ligament in bimalleolar ankle fractures after medial malleolar fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:843–8.

Miller CD, Shelton WR, Barrett GR, Savoie FH, Dukes AD. Deltoid and syndesmosis ligament injury of the ankle without fracture. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:746–50.

Park SS, Kubiak EN, Egol KA, Kummer F, Koval KJ. Stress radiographs after ankle fracture: the effect of ankle position and deltoid ligament status on medial clear space measurements. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:11–8.

Schuberth JM, Collman DR, Rush SM, Ford LA. Deltoid ligament integrity in lateral malleolar fractures: a comparative analysis of arthroscopic and radiographic assessments. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;43:20–9.

van den Bekerom MP, Mutsaerts EL, van Dijk CN. Evaluation of the integrity of the deltoid ligament in supination external rotation ankle fractures: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:227–35.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data of this study were real and were performed in SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). The statistical results of the data are presented in this main paper. The images of case examples are depicted in this research article. All of the data are available in contact with the correspondence author.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2017 M613178), and Shaanxi Province Natural Science Foundation Research Project (2014JQ4164, 2014JM2–8175).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZHM and LXJ designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. HDJ and LJ participated in the design of the study and analyzed the data. ZF, LY and WXD collected the data, followup of patients and helped in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the ethical committee of Honghui Hospital. We have obtained written consent to participate from the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, HM., Lu, J., Zhang, F. et al. Surgical treatment of ankle fracture with or without deltoid ligament repair: a comparative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18, 543 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1907-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1907-4