Abstract

Background

Targeted treatment, matched according to specific clinical criteria e.g. hip muscle weakness, may result in better outcomes for people with patellofemoral pain (PFP). However, to ensure the success of future trials, a number of questions on the feasibility of a targeted treatment need clarification. The aim of the study was to explore the feasibility of matched treatment (MT) compared to usual care (UC) management for a subgroup of people with PFP determined to have hip weakness and to explore the mechanism of effect for hip strengthening.

Methods

In a pragmatic, randomised controlled feasibility study, 24 participants with PFP (58% female; mean age 29 years) were randomly allocated to receive either MT aimed specifically at hip strengthening, or UC over an eight-week period. The primary outcomes were feasibility outcomes, which included rates of adherence, attrition, eligibility, missing data and treatment efficacy. Secondary outcomes focused on the mechanistic outcomes of the intervention, which included hip kinematics.

Results

Conversion to consent (100%), missing data (0%), attrition rate (8%) and adherence to both treatment and appointments (>90%) were deemed successful endpoints. The analysis of treatment efficacy showed that the MT group reported a greater improvement for the Global Rating of Change Scale (62% vs. 9%) and the Anterior Knee Pain Scale (−5.23 vs. 1.18) but no between-group differences for either average or worst pain. Mechanistic outcomes showed a greatest reduction in peak hip internal rotation angle for the MT group (13.1% vs. −2.7%).

Conclusion

This feasibility study indicates that a definitive randomised controlled trial investigating a targeted treatment approach is achievable. Findings suggest the mechanism of effect of hip strengthening may be to influence kinematic changes in hip function in the transverse plane.

Trial registration

This study was registered retrospectively. ISRCTN74560952. Registration date: 2017–02-06.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is widely considered an enigma of musculoskeletal medicine [1]. It has been reported to affect six to 7 % of the adolescent population [2] and one in six adults who consult their GP with knee pain will be diagnosed with PFP [3]. Of major concern is that recent studies have shown that 40 to 62% [2, 4] of individuals with PFP, at one-year follow-up, report unfavourable outcomes following treatment according to current paradigms.

One solution for improving PFP therapy, proposed by the international PFP community, is to establish subgroups of the wider PFP population, to allow targeted treatment, matched according to specific subgroup characteristics [5,6,7]. Currently, a multimodal treatment approach (a combination of individual treatments) is recommended as best practice [8]. However, it is likely that people with PFP will benefit from being stratified and matched to specific interventions [9]. Despite successive international consensus papers since 2011 recommending subgrouping [5,6,7, 10], very little literature has focused on subgrouping and targeted therapy. A small number of studies [11,12,13,14,15] have targeted treatment based on single clinical features, although no definitive studies exist to support targeted interventions in PFP.

Reduced hip muscle strength is considered an associated feature of PFP [16]. A number of authors have reported promising clinical outcomes after prescribing hip strengthening exercises for people with PFP [17,18,19,20,21]. It has been proposed that individuals with PFP present with a propensity towards increased hip adduction and internal rotation during dynamic movement [22]. This is a significant predictor of pain in PFP [23], thought to be linked to increasing patellofemoral joint contact stress [24]. Subsequently, correcting this altered movement pattern is often seen as a desired outcome in interventional studies [25].

There are however, conflicting findings around the mechanistic effect of hip strengthening in PFP [25]. Some studies have demonstrated a post-interventional change in kinematics [17, 26], whilst others have reported no change [27, 28]. The reason for these conflicting findings is unclear, however, the previous studies showing no kinematic change [27, 28] have included athletic cohorts and with one of the cohorts [27] clearly showing a higher than normal baseline strength. Selfe et al. (2016) [29] recently classified people with PFP into three subgroups: ‘strong’ , ‘weak and tighter’ and ‘weak and pronated foot’. Notably, 22% were classified into the ‘strong’ subgroup with higher knee extension and hip abduction strength that may not gain from a treatment approach based on strengthening. A strengthening intervention would likely have the greatest effect on the kinematics of those with baseline weakness.

Large trials exploring a stratified approach for PFP are required, however, to ensure the success and effectiveness of such trials, a number of feasibility questions need to be answered. The primary purpose of this study was therefore to explore the feasibility of treatment matched to the specific clinical criteria of a selected subgroup compared to usual care (UC) management to inform a future stratified approach to PFP treatment. The a priori selection of a subgroup with a specific characteristic such as hip abductor weakness also provides the opportunity, as a secondary aim, to explore the mechanism of effect as this has also been recently advocated for trials of physical interventions [30].

Methods

Study design

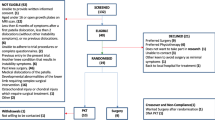

The study was a pragmatic, randomised controlled feasibility study in which participants were selected from an on-going longitudinal cohort study. Twenty-six participants were identified from larger group of 70 PFP cases on the basis of having hip abductor weakness at clinical examination and were randomised into receiving either a matched treatment (MT) or UC in a 1:1 ratio. Ethical approval was obtained prior to commencement of the study (14/NE/1131). All participants completed written informed consent prior to entering the study. The study has been reported in accordance with Consolidate Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [31] and Template for Intervention Description and Replication guidelines. (TiDieR) [32].

Participants

Participants were recruited between November 2014 to April 2016 from a large musculoskeletal and rehabilitation service via clinician referrals, their SystmOne database (a local electronic healthcare database), posters displayed in the local hospital and an university alumni volunteers website. Eligibility criteria were assessed both verbally and clinically to ensure that the inclusion criteria were addressed fully (Table 1). The most symptomatic knee was designated the index limb. Participants were stratified based on hip abductor strength measured using a Biodex isokinetic system 4 (IRPS Mediquipe, UK). Hip abductor weakness was based on thresholds defined a priori from age and gender normative data [33] (Table 1). The relevant normative mean minus one standard deviation (−1 SD) was used as the threshold for allocation to the “weak” stratum based on previous recommendations [34].

Sample size

The study was designed to recruit 12 participants per group based on previous guidance for feasibility studies of this design [35]. Participants were followed up to 8 weeks post-intervention as this has previously shown to be sufficient time to demonstrate an effect in PFP [20, 27, 36].

Randomisation

The random allocation sequence was made according to the output from a random number generator and concealed within pre-sealed, opaque envelopes [37]. All allocation and randomisation was conducted by the lead author (BD).

Blinding

The outcome assessor was unblinded, however, patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) were completed in a separate room with no input from the assessor. The biomechanical outcomes were acquired in accordance to a strict study protocol to minimise variation and bias [38]. Furthermore, the biomechanical outputs are automated so the lack of blinding is less of an issue.

Interventions

Participants randomised to the MT group were asked to attend six supervised sessions of approximately 30 min in duration once per week for 6 weeks at a local hospital. Each week they also performed two additional sessions on non-consecutive days independently at home, with the intervening days allowing adequate rest [39]. Consideration was made to the recommended determinants of resistance exercise [40] when developing the study intervention. The sessions were face to face, 1:1 sessions provided by the lead author (BD) a senior musculoskeletal physiotherapist with over 8 years of clinical experience. During these sessions, participants were given education and justification of the treatment followed by three exercises aimed at targeting coronal, sagittal and transverse strength of the hip using resistance bands. Each week at least one of the exercises would change with the aim of providing variation and minimising tedium [41]. The supervision sessions served as a means of ensuring both treatment fidelity and tailoring. Fidelity was ensured by checking the exercise technique and making corrections to performance prior to these being performed independently at home. Subsequent visits ensured this instruction had been correctly applied or not. Tailoring the intervention based on progressive loading was in line with current recommendations [25]. Participants were issued yellow (least resistance), red or green (most resistance) resistance tubing (66fit Ltd. ™) and were allowed to take it home. To progress the load and resistance, a Borg Rate of Perceived Exertion scale (RPE) [42] was used based on the recommendations when using resistance band [43]. A RPE of >6 was considered desirable [39] and participants were monitored after a few repetitions to ensure this was what was being achieved. As participants were stratified for strength, the intervention required participants to perform 10 repetitions within three sets as recommended for strength training [39]. Participants were advised to ensure the time under tension was 8 s (3 s concentric, 2 s isometric hold and 3 s eccentric contraction). Strengthening was performed on each leg alternatively providing a standardised rest between sets. Exercise diaries (see Additional file 1) were issued to participants to provide a reminder of the exercises and to allow a measure of adherence. Participants were asked to document each time each exercise was performed on their diary sheet and return these at each visit.

Participants randomised to the UC group continued with the same management of their condition as they were planning to receive prior to the commencement of the study. This included planned physiotherapy, podiatry or no intervention, depending upon participant preference. The type of management and number of sessions was recorded for the UC group at follow-up.

Outcomes

In response to lack of agreed guidelines for outcomes in feasibility studies [44], the primary feasibility outcomes were adapted from recommendations made by Bugge et al. (2013) [45] and Shanyinde et al. (2011) [46].

Feasibility outcomes

Recruitment & eligibility

Recruitment and eligibility was assessed using the rate of eligibility (%), the conversion of eligible to consent (%) and a breakdown of recruitment sources.

Randomisation & blinding

The success of randomisation was assessed based on any problems being highlighted and whether the randomisation process yielded broad equality in both groups based on the difference in baseline characteristics. Intervention blinding is not possible for a physiotherapeutic intervention of this nature [47] and thus this could not be measured.

Adherence & acceptability

Adherence was assessed by the adherence rate to treatment (%) using exercise diaries and adherence to appointments (%) based on the number of ‘unable to attends’ (UTAs). The acceptability was assessed by the attrition rate (%).

Outcome measures

The outcome data was assessed based on the amount of missing data (%) found in each case report form.

Resources & study management

The study management was assessed qualitatively in terms of the logistics of running the study and the safety of all study components.

Treatment efficacy

PROMs provided assessments of the efficacy of the study in terms of improvements in pain and disability at eight-week follow-up. The following outcomes were selected based on current IMMPACT guidelines [48]:

-

1.

Pain was assessed using two numerical rating scales (NRS) with a 11 point scale for: i) the average pain in the knee over the last week ii) the worst pain in the knee over the last week.

-

2.

Function was assessed using the Anterior Knee Pain scale (AKPS), a 13-item knee specific self-reported questionnaire [49] in which 100 is the maximum achievable score and lower scores indicate greater pain and disability

-

3.

Rating of change measured on a 11-point global rating of change scale (GROC) anchored with “very much worse” to “completely recovered” [50]. Responses were dichotomised with values greater than 0 (“unchanged”) indicating an improvement.

Mechanistic outcomes

The secondary aim of the study explored the potential mechanistic effects of hip strengthening on the selected sample. A selection of biomechanical variables were selected a priori to prevent subsequent data mining [51].

Three-dimensional kinematics were assessed during stair descent using a VICON, motion capture system (Vicon Nexus Version 1.6; Vicon Motion Systems, Oxford Metrics, Oxford, Uk) at a sampling rate of 200 Hz. The stair set-up and procedure is shown Fig. 1. Stair descent was selected as this is a known aggravating factor for PFP [52], deemed challenging enough to observe a kinematic change [53] but achievable for both active and sedentary participants. Further procedural details are available in Additional file 2.

Stairs and platform used in the study. Participants descended the stairs at a self-selected speed. Each participant completed a minimum five successful stair descents. The descent was deemed successful when the index limb was placed on step two in the absence of any stumbles or hesitation. The gait cycle of interest was similar to that used in previous studies [66] between step two and ground floor. The variables of interest were captured during stance phase; between toe on and toe off on step two

Data collected was analysed in Visual 3D (C-Motion, Rockville, Maryland). The pre-selected kinematics of most theoretical interest for explaining the proposed mechanism of action of the MT intervention were i) peak hip internal rotation angle (peak IR) of the thigh with respect to the pelvis; ii) peak hip adduction angle (peak ADD) of the thigh with respect to the pelvis; iii) total coronal hip range of movement (coronal ROM); iv) total transverse hip (ROM) (transverse ROM). These were calculated using the an X-Y-Z Cardan rotation sequence [54]. A reduction in the magnitude of all the kinematic variables measured post-intervention was considered a favourable outcome.

A Biodex isokinetic system 4 (IRPS Mediquipe, UK) was used to assess muscle strength. Both limbs were tested, with the index limb tested after a practice test using the contralateral limb. Testing the index limb second minimises any learning-effect variability [55]. To ensure accuracy, the Biodex calibration verification procedure was conducted uniformly in accordance with the system operation manual. Further procedural details are available in Additional file 3. Data was collected by Biodex Advantage Software (IRPS Mediquipe, UK). The isokinetic strength measures of interest were i) peak hip abduction torque based on the maximum hip abduction torque across five repetitions; ii) Peak knee extension torque based on the maximum knee extension torque across five repetitions.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS (version 21.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). As hypothesis testing is not advised for this size and type of study design [44], descriptive statistics along with point estimates, confidence intervals and effect sizes were presented for all PROMs and biomechanical outcomes. Within-group changes for all kinematic variables were expressed as a percentage change of the total ROM. Feasibility outcomes were described using descriptive statistics. To determine, where possible, a quantifiable measure of the feasibility outcomes, predetermined thresholds were used to indicate either success or strategies required (Table 2). Where it was not possible to use quantitative data to demonstrate success, outcomes were reported narratively.

Results

Feasibility outcomes

Figure 2 shows that 14 participants were randomised to MT and 12 participants to UC. Of the participants in the UC group, 55% received formal physiotherapy treatment, which may or may not have included a strengthening component. The remaining UC participants reported continuing with their normal self-management.

Recruitment & eligibility

Over 15 months, of the 70 who were screened, 26 were eligible based on hip weakness, an eligibility rate of 37.1%. All 26 eligible participants consented to the study (100% conversion to consent). Recruitment was predominantly from the SystmOne database 54% (14/26). Direct clinician referrals 15% (4/26), posters 23% (6/26) and a university alumni online advert 8% (2/26) accounted for the other sources of recruitment.

Randomisation and blinding

No practical problems were highlighted in the randomisation procedure. The randomisation yielded reasonable equality in terms of demographics and baseline symptoms (see Table 3). The only notable difference was the larger number of people with bilateral knee pain in the MT compared to the UC group (64% vs. 33.3% respectively).

Adherence & acceptability

At post-treatment follow-up, two participants did not complete the study, an attrition rate of 8%. In the MT group, one participant did not attend their second treatment session and was then lost to contact. In the UC group, one participant was unable to complete the post-treatment analysis due to work commitments. Table 4 illustrates that of the MT group, five participants reported a 100% adherence to treatment with an overall average adherence to treatment of 94%. Treatment sessions required rearranging on seven occasions; three times for illness, three times for work commitments and once for childcare. This shows an adherence to appointment rate of 92%. Adherence to treatment and appointments was not relevant to in the UC group.

Outcome measures

All questionnaires were completed fully without any missing data yielding a missing data indicator of 0%.

Treatment efficacy

Based on the GROC, overall the MT group demonstrated a larger improvement compared to UC group (61.54% vs. 9.09% respectively). The MT group demonstrated a greater improvement in AKP score compared to UC group (Mean Difference (MD) -6.41, 95% CI: 14.23, 1.41) with a medium effect size (d = 0.70) (see Table 5). Both worst pain NRS (−0.41; 95% CI: -1.93, 1.12) and average pain NRS (−0.02, 95% CI: -1.01.

Resources & Study Management

The 9% of appointments that needed rescheduling required time to make these changes. No safety issues were reported.

Mechanistic outcomes

The results from the mechanistic outcomes are shown in Table 6. Evaluation of the peak torque measures showed that both MT and UC groups showed an increase in peak hip abductor torque from baseline to follow up but no evidence of a systematic effect between groups was observed (−0.63 Nm; 95% CI: -13.35, 12.09). In terms of peak knee extensor torque, the UC group showed a much larger increase yielding a MD of 7.96 Nm (95% CI -2.88, 18.79; d = 0.624).

The between-group comparisons of the kinematics showed that the MT group had a reduction in peak IR whereas the UC had a slight increase (1.70°; 95% CI: −2.56, 5.97) yielding a small effect size (d = −0.34). Both MT and UC groups showed an increase in peak ADD (−0.17° vs. -0.04° respectively). Coronal ROM showed that the MT group had a reduction whereas the UC group showed a slight increase (1.12°; 95% CI: −0.72, 3.06) yielding a medium effect size (d = −0.53). Transverse ROM showed an increase in both the MT and UC groups (−0.32° vs. -0.78° respectively.

The within-group comparisons of the kinematic outcomes are presented in Fig. 3. The MT intervention led to a reduction in peak IR of 13.1% of the total transverse ROM. There was a small reduction in coronal ROM (4.8%) whilst peak ADD and transverse ROM demonstrated a small increase. The UC group demonstrated an increase for all kinematic variables.

Discussion

The aims of this study were: i) to determine the feasibility of treatment matched to the specific characteristics of selected PFP sub group and ii) to explore the proposed mechanism of effect of employing strengthening in a subgroup with baseline hip weakness. A definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) appears achievable in terms of adherence, attrition, eligibility and outcome data. Some consideration is required to develop strategies to enhance the ability to quantify clinical differences between groups. In terms of the potential mechanism of effect for hip strengthening, an improvement was shown for peak IR following MT.

Feasibility outcomes

Based on our eligibility thresholds for selecting a ‘weak’ hip group, we predetermined that for feasibility; eligibility should reach or exceed 32%. Our observed eligibility rate of 37% provides reassurance. It is also expected that other people with PFP, ineligible for the current study based on hip strength, may well classify into other subgroups as shown in recent studies [29]. This eligibility rate for hip weakness is less than the 88% (at 1SD) reported by Selfe et al. (2016) [29] but may be explained by the current study measuring an isokinetic contraction rather than an isometric contraction and as a consequence the different strength thresholds applied. Furthermore in order to minimise potential bias, future multicentre RCTs would need to ensure cross-site calibration of the isokinetic systems and site visits to monitor fidelity of the testing procedures and the intervention.

Recent studies have reported that a greater adherence to treatment is associated with increased probability of better outcomes [2]. An adherence to treatment and adherence to appointments over 90% is promising. Approximately 30% (4/13) achieved complete adherence to all treatment sessions and 9% of appointments required rearranging. Our adherence rate is comparable to a larger RCT [18] who found a 80.3% adherence rate for a 6 week hip strengthening in PFP. It’s anticipated that rearranging appointments for participants would be more challenging for a larger sample over multiple sites. Consequently, strategies to enhance adherence with the use of activity monitoring technology and reminder services need to be considered [56].

No differences between groups were found for either the average or worst NRS values. This might be explained by the difference in almost a score of one in average baseline NRS, a feature that would likely be minimised in a larger full-scale trial. Previous RCTs [18, 57] have also used eligibility criteria requiring a minimum NRS score of three out of 10 pain score. Setting a minimum pain score as part of the inclusion criteria is suggested for a future RCT.

The difference between groups for the AKP score did not reach the predetermined minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of eight points [58], although there was a trend towards a meaningful benefit. These findings are similar to the only other RCT to have stratified a PFP cohort, used in a study of a foot orthotic intervention over 6 weeks. Mills et al. (2011) [12] selected their participants based on predictors shown to predict success with orthotics, which included age, height, baseline pain severity and a static foot measure. They also found a significant difference between groups in terms of GROC with no differences in AKP score or VAS pain. They suggest that GROC is able to capture the multidimensional nature of PFP (characterised by pain, disability and functional limitation) compared to AKP score and VAS pain which are more one dimensional [12].

Mechanistic outcomes

Stratifying for hip abductor weakness led to a reduction of approximately 13% for peak IR in the MT group following strengthening treatment. This is important considering that an increase peak IR has been associated with PFP during stair descent [59, 60]. This reduction in peak IR occurred with a slight worsening of their transverse ROM suggesting that following treatment, people in the MT group were initiating stance phase in a more desirable externally rotated hip position. A reduction in peak IR and a slight increase in peak ADD are perhaps surprising considering that participants were stratified for hip abductor weakness. However, recent strength measures conducted on 501 healthy athletes [61] have shown that hip abductor and hip external rotation strength are highly correlated (r = 0.66) indicating this subgroup were likely to have also demonstrated weakness into both hip abduction and external rotation.

Hip strength increased in both groups by a similar difference, which is likely the result of over a third of participants in the UC group being engaged in physiotherapy. Post-hoc analysis of those participants in the UC group who received no treatment show an increase of only 3.9 Nm in hip abductor strength (results not shown). In the MT group the change in hip strength was 9%, which is a comparable improvement to previous hip strengthening programmes over a similar training duration [21, 27]. The increase in strength for both groups but with only kinematic improvements seen in the MT group might suggest that strength, on its own, cannot explain the improvement seen in peak IR. Direct comparison with previous studies [17, 26,27,28] remains difficult due to the differences in assessment tasks (e.g. running, stairs etc.) and the specific kinematic outcomes (e.g. peak, average angles etc.) investigated. Previous studies [27, 28] that have observed the effect of hip strengthening on running kinematics in people with PFP found no change in kinematics despite increases in hip abductor strength. Only Baldon et al. (2014) [17] reported changes in kinematics, during a single leg squat, following a hip strengthening programme. Yet, this training programme, did include constant feedback on lower limb alignment which suggests a more movement retraining approach [62] rather than pure strength training. It remains possible that the improvements observed in peak IR in the current study was the result of using progressive loading within a tailored treatment regime and selecting participants who were most likely to benefit from strengthening.

Limitations

This feasibility study presents with several limitations. Firstly, the study was performed in a single centre. Future RCTs would be required to be multicentre to improve generalisability, which is anticipated to introduce new feasibility issues. The findings of the current study would, however, inform the documentation of standard operating procedures in terms of recruitment; data collection and intervention provision to ensure any future study could be operationalised across different geographical locations. Secondly, the current study did not blind assessors to group allocation, which could lead to potential bias [63]. Every effort was made for participants to complete PROMs in isolation and objective biomechanical outcomes were acquired in accordance with strict protocols with little chance of introducing bias. Future RCTs should make every effort to introduce outcome assessor blinding and consider measuring the level of this outcome assessor blinding [64] Thirdly, the use of a UC group was intended to represent the heterogeneity of management available in real, daily practice and thus improve the external validity [65]. For the purposes of exploring the mechanism of hip strengthening, however, the fact that over half of the UC group received physiotherapy input potentially dilutes the between-group findings. Comparison with a control group receiving no active intervention would remedy this issue.

Conclusion

The potential benefits associated with stratification and subgrouping within PFP have been advocated since the first International Patellofemoral Pain Retreat Consensus statement [10]. This study suggests that targeted treatment provides a greater improvement in overall function and self-reported improvement in comparison to usual care. Additionally, the improvements seen in peak IR following MT suggest this may be a plausible mechanism of effect for hip strengthening when treatment is matched to an appropriate subgroup. Strategies to enhance the ability to detect clinical difference should be considered and might be improved by selection of participants with a minimum pain score. Ultimately, a pragmatic, multicentre RCT with a sufficiently powered cohort appears achievable and should be conducted to determine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a stratified treatment approach versus usual care for people with PFP.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

three dimensional

- AKPS:

-

anterior knee pain scale

- CONSORT:

-

consolidated standards of reporting trials

- Coronal ROM:

-

total coronal hip range of movement

- GP:

-

general practitioner

- GROC:

-

global rating of change scale

- MCID:

-

minimal

- MT:

-

matched treatment

- Nm:

-

Newton metre

- NRS:

-

numerical rating scale

- Peak ADD:

-

peak hip adduction angle

- Peak IR:

-

peak hip internal rotation angle

- PFP:

-

patellofemoral pain

- PROM:

-

patient reported outcome measures

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

- ROM:

-

range of movement

- RPE:

-

rate of perceived exertion

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- TiDieR:

-

template for intervention description and replication guidelines

- Transverse ROM:

-

total transverse hip range of movement

- UC:

-

usual care

- UTA:

-

unable to attend

IMMPACT

Initiative on Methods, Measurements and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials

References

Dye SF. The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: a tissue homeostasis perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;436:100–10.

Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S, and Roos EM. Is knee pain during adolescence a self-limiting condition? Prognosis of patellofemoral pain and other types of knee pain. Am J Sports Med. 2016. doi:10.1177/0363546515622456.

Wood L, Muller S, Peat G. The epidemiology of patellofemoral disorders in adulthood: a review of routine general practice morbidity recording. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2011;12(2):157–64.

Collins NJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Crossley KM, et al. Prognostic factors for patellofemoral pain: a multicentre observational analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(4):227–33.

Crossley KM, van Middelkoop M, Callaghan MJ, et al. 2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 2: recommended physical interventions (exercise, taping, bracing, foot orthoses and combined interventions). Br J Sports Med. 2016. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096268.

Powers CM, Bolgla LA, Callaghan MJ, Collins N, Sheehan FT. Patellofemoral pain: proximal, distal, and local factors, 2nd international research retreat. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(6):A1–54.

Witvrouw E, Callaghan MJ, Stefanik JJ, et al. Patellofemoral pain: consensus statement from the 3rd international Patellofemoral pain research retreat held in Vancouver, September 2013. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(6):411–4.

Barton CJ, Lack S, Hemmings S, Tufail S, and Morrissey D. The 'Best Practice Guide to Conservative Management of Patellofemoral Pain': incorporating level 1 evidence with expert clinical reasoning. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:923–34.

Callaghan MJ. Will Sub-classification of Patellofemoral Pain Improve Physiotherapy Treatment?, in Sports Injuries. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 571–77.

Davis IS, Powers C. Patellofemoral pain syndrome: proximal, distal, and local factors—international research retreat, April 30–may 2, 2009, Baltimore, Maryland. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(3):A1–A48.

Eng JJ, Pierrynowski MR. Evaluation of soft foot orthotics in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Phys Ther. 1993;73(2):62–8. discussion 68-70

Mills K, Blanch P, Dev P, Martin M, and Vicenzino B. A randomised control trial of short term efficacy of in-shoe foot orthoses compared with a wait and see policy for anterior knee pain and the role of foot mobility. Br J Sports Med. 2011. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090204.

Noehren B, Scholz J, and Davis I. The effect of real-time gait retraining on hip kinematics, pain and function in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Br J Sports Med. 2010. bjsports69112. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.069112.

Willy RW, Davis IS. The effect of a hip-strengthening program on mechanics during running and during a single-leg squat. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(9):625–32.

Johnston LB, Gross MT. Effects of foot orthoses on quality of life for individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(8):440–8.

Rathleff M, Rathleff C, Crossley K, and Barton C. Is hip strength a risk factor for patellofemoral pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093305.

Baldon RDM, Serrão FV, Scattone Silva R, Piva SR. Effects of functional stabilization training on pain, function, and lower extremity biomechanics in women with patellofemoral pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(4):240–A8.

Ferber R, Bolgla L, Earl-Boehm JE, Emery C, Hamstra-Wright K. Strengthening of the hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Athl Train. 2015;50(4):366–77.

Fukuda TY, Melo WP, Zaffalon BM, et al. Hip posterolateral musculature strengthening in sedentary women with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled clinical trial with 1-year follow-up. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(10):823–30.

Khayambashi K, Mohammadkhani Z, Ghaznavi K, Lyle MA, Powers CM. The effects of isolated hip abductor and external rotator muscle strengthening on pain, health status, and hip strength in females with patellofemoral pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(1):22–9.

Nakagawa TH, Muniz TB, de Marche BR, et al. The effect of additional strengthening of hip abductor and lateral rotator muscles in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(12):1051–60.

Noehren B, Hamill J, Davis I. Prospective evidence for a hip etiology in patellofemoral pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(6):1120–4.

Nakagawa T, Serrão F, Maciel C, Powers C. Hip and knee kinematics are associated with pain and self-reported functional status in males and females with patellofemoral pain. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(11):997–1002.

Liao TC, Yang N, Ho KY, Farrokhi S, Powers CM. Femur rotation increases patella cartilage stress in females with Patellofemoral pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(9):1775–80.

Lack S, Barton C, Sohan O, Crossley K, and Morrissey D. Proximal muscle rehabilitation is effective for patellofemoral pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094723.

Mascal CL, Landel R, Powers C. Management of patellofemoral pain targeting hip, pelvis, and trunk muscle function: 2 case reports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(11):647–60.

Earl JE, Hoch AZ. A proximal strengthening program improves pain, function, and biomechanics in women with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):154–63.

Ferber R, Kendall KD, Farr L. Changes in knee biomechanics after a hip-abductor strengthening protocol for runners with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):142–9.

Selfe J, Janssen J, Callaghan M, et al. Are there three main subgroups within the patellofemoral pain population? A detailed characterisation study of 127 patients to help develop targeted intervention (TIPPs). Br J Sports Med. 2016. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094792.

Felson DT, Redmond AC, Chapman GJ, et al. Recommendations for the conduct of efficacy trials of treatment devices for osteoarthritis: a report from a working group of the Arthritis Research UK osteoarthritis and crystal diseases clinical studies group. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(2):320–6.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):1.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Bartels E, Bülow P, et al. Isokinetic and isometric muscle strength in a healthy population with special reference to age and gender. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2009;197(s673):1–68.

Redmond AC, Crane YZ, Menz HB. Normative values for the foot posture index. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1(1):1.

Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat. 2005;4(4):287–91.

Dolak KL, Silkman C, McKeon JM, et al. Hip strengthening prior to functional exercises reduces pain sooner than quadriceps strengthening in females with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(8):560–70.

Torgerson DJ, Roberts C. Randomisation methods: concealment. BMJ. 1999;319(7206):375–6.

Kahan BC, Cro S, Doré CJ, et al. Reducing bias in open-label trials where blinded outcome assessment is not feasible: strategies from two randomised trials. Trials. 2014;15(1):1.

Ratamess N, Alvar B, Evetoch T, et al. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults [ACSM position stand]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687–708.

Toigo M, Boutellier U. New fundamental resistance exercise determinants of molecular and cellular muscle adaptations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;97(6):643–63.

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):674–88.

Day ML, McGuigan MR, Brice G, Foster C. Monitoring exercise intensity during resistance training using the session RPE scale. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(2):353–8.

Waryasz GR, McDermott AY. Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS): a systematic review of anatomy and potential risk factors. Dyn Med. 2008;7(1):1.

Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(2):307–12.

Bugge C, Williams B, Hagen S, et al. A process for decision-making after pilot and feasibility trials (ADePT): development following a feasibility study of a complex intervention for pelvic organ prolapse. Trials. 2013;14(1):1.

Shanyinde M, Pickering RM, Weatherall M. Questions asked and answered in pilot and feasibility randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):1.

Rushton A, Calvert M, Wright C, Freemantle N. Physiotherapy trials for the 21st century–time to raise the bar? J R Soc Med. 2011;104(11):437–41.

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19.

Kujala UM, Jaakkola LH, Koskinen SK, et al. Scoring of patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(2):159–63.

Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J Man Manip Ther. 2013.

Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Data dredging, bias, or confounding. BMJ. 2002;325(7378):1437–8.

Crossley KM, Callaghan MJ, van Linschoten R. Patellofemoral pain. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(4):247–50.

Barton CJ, Levinger P, Crossley KM, Webster KE, Menz HB. The relationship between rearfoot, tibial and hip kinematics in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2012;27(7):702–5.

Grood ES, Suntay WJ. A joint coordinate system for the clinical description of three-dimensional motions: application to the knee. J Biomech Eng. 1983;105(2):136–44.

Lund H, Søndergaard K, Zachariassen T, et al. Learning effect of isokinetic measurements in healthy subjects, and reliability and comparability of Biodex and lido dynamometers. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2005;25(2):75–82.

McLean SM, Burton M, Bradley L, Littlewood C. Interventions for enhancing adherence with physiotherapy: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(6):514–21.

Collins N, Crossley K, Beller E, et al. Foot orthoses and physiotherapy in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome: randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1735.

Crossley KM, Bennell KL, Cowan SM, Green S. Analysis of outcome measures for persons with patellofemoral pain: which are reliable and valid? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):815–22.

Souza RB, Powers CM. Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(1):12–9.

McKenzie K, Galea V, Wessel J, Pierrynowski M. Lower extremity kinematics of females with patellofemoral pain syndrome while stair stepping. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(10):625–32.

Khayambashi K, Ghoddosi N, Straub RK, Powers CM. Hip muscle strength predicts noncontact anterior Cruciate ligament injury in male and female athletes a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(2):355–61.

Neal BS, Barton CJ, Gallie R, O’Halloran P, Morrissey D. Runners with patellofemoral pain have altered biomechanics which targeted interventions can modify: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2016;45:69–82.

Karanicolas PJ. Practical tips for surgical research: blinding: who, what, when, why, how? Can J Surg. 2010;53(5):345.

Lowe CM, Wilson M, Sackley C, Barker K. Blind outcome assessment: the development and use of procedures to maintain and describe blinding in a pragmatic physiotherapy rehabilitation trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(3):264–74.

Smelt AF, van der Weele GM, Blom JW, Gussekloo J, Assendelft WJ. How usual is usual care in pragmatic intervention studies in primary care? An overview of recent trials. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(576):e305–e18.

Mian OS, Thom JM, Narici MV, Baltzopoulos V. Kinematics of stair descent in young and older adults and the impact of exercise training. Gait Posture. 2007;25(1):9–17.

Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):283–91.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Kay Crossley of La Trobe University, Melbourne and Claire Robertson of Wimbledon Clinics, London for their insightful comments regarding the development of the intervention and to both Dr. David Lunn and Dr. Graham Chapman of University of Leeds for their guidance on the motion capture analysis.

Funding

BTD is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship (CDRF -2013-04-044); PGC and ACR are in part supported through the NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, Leeds, UK. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. This work was also supported in part by funding from the Arthritis Research UK Experimental Osteoarthritis Treatment Centre (Ref 20,083) and the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Sport, Exercise and Osteoarthritis (Ref 20,194).

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting the present findings and methods are contained within the manuscript and Additional files 1, 2 and 3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BTD takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to the finished manuscript. Conception & design: BTD, PGC, ACR, JS and TOS. Collection & Assembly of Data: BTD, ACR and PGC. Analysis & Interpretation of the data: BTD, PGC, ACR, JS and TOS. Drafting & final approval of the manuscript: BTD, PGC, ACR, JS and TOS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to randomisation and the study was approved by the North East - Newcastle & North Tyneside 2 Research Ethics Committee (14/NE/1131); NHS Health Research Authority (IRAS 154658).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of clinical images was obtained from all patients. Copies of the consent forms are available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Home Exercise Training Diary. (PDF 1211 kb)

Additional file 2:

Procedures for capturing 3D kinematics. (PDF 72 kb)

Additional file 3:

Procedures for obtaining strength. (PDF 74 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Drew, B.T., Conaghan, P.G., Smith, T.O. et al. The effect of targeted treatment on people with patellofemoral pain: a pragmatic, randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18, 338 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1698-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1698-7