Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to provide an overview of the literature addressing the role of genetic factors and biomarkers predicting pain recovery in newly diagnosed lumbar radicular pain (LRP) patients.

Methods

The search was performed in Medline OVID, Embase, PsycInfo and Web of Science (2004 to 2015). Only prospective studies of patients with LRP addressing the role of genetic factors (genetic susceptibility) and pain biomarkers (proteins in serum) were included. Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed methodological quality.

Results

The search identified 880 citations of which 15 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Five genetic variants; i.e., OPRM1 rs1799971 G allele, COMT rs4680 G allele, MMP1 rs1799750 2G allele, IL1α rs1800587 T allele, IL1RN rs2234677 A allele, were associated with reduced recovery of LRP. Three biomarkers; i.e., TNFα, IL6 and IFNα, were associated with persistent LRP.

Conclusion

The present results indicate that several genetic factors and biomarkers may predict slow recovery in LRP. Still, there is a need for replication of the findings. A stricter use of nomenclature is also highly necessary.

Trial registration

The review is registered PROSPERO 20th of November 2015. Registration number is CRD42015029125.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Low back pain (LBP) has a lifetime prevalence of 70% [1]. The annual prevalence of lumbar radicular pain (LRP) in the population is estimated to 2–3% [2, 3]. Hence, LRP, also referred to as “sciatica”, account for 5–10% of the low back pain conditions. However, the disability is worse and the recovery is slower for LRP than for other low back pain conditions [3, 4]. Low back disorders constitute an important source of disability and are among the most cost-intensive health problems [5].

Development of persistent low back pain and sciatica may be associated with ergonomic strains, but also psychosocial aspects. Risk factors such as age, smoking, body weight, height, occupational load and mental stress contribute to LRP [2, 3, 6–8]. Clearly, many psychosocial factors predict poor recovery in LRP [6, 9]. In addition, genetic variability may influence the risk of a chronic outcome [10, 11].

LRP is characterized by radiating pain that typically follows the dermatome of the affected nerve root from the lumbar or sacral spine [12]. Previous data suggest that discharges emanating from the dorsal nerve roots or their ganglions explain the radiating nature of this form of back disorder [13]. LRP may be induced by mechanical compression of the nerve root, but also by the biochemical influence on the neuronal tissues caused by a local inflammatory process. Moreover, leak of nucleus pulposus from herniated discs may have many effects on the nerves inducing histological changes and increased neuronal excitability. Microvascular changes close to the dorsal ganglion, spinal nerve roots and spinal cord is a part of the pathogenesis [14, 15].

Environmental factors including heavy work load is assumed to contribute to acceleration of degeneration of the spinal joints and discs, but also genetic factors are of importance [10]. It has been postulated that heritability for back pain range from 30 to 45% [16]. The genetic susceptibility for LBP and LRP may be associated with genetic variability in genes related to modulation of nociceptive processing, tissue degeneration and local or systemic inflammation.

In particular genetic variability important for opioid, dopaminergic, adrenergic and serotonergic signaling may affect modulation of nociceptive processing [17–19]. Several previous studies demonstrate a link between genetic variability in the gene encoding opioid receptor mu 1 (OPRM1) and LRP [20, 21]. Earlier reviews, for example Diatchenko et al. [22], highlight that genetic factors related to the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) affect cortical pain processing and the risk of chronic LBP.

Genetic variability in the gene encoding the sodium ion channel (SCN9A) [23] and the GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) [24] gene may affect LRP, indicating that genetic factors may affect peripheral nerves as well. GCH1 is an enzyme involved in production of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). BH4 is an essential cofactor for catecholamine, serotonin and nitric oxide production. Earlier data also suggest that disc degeneration and the clinical outcome after sciatica may be associated with the large molecule collagen type IX alpha 2 (COL9A2) [25]. Thus, previous data show possible association between genetic markers and lumbar disc degeneration. However, the relationship between degenerative changes and persistence of pain is still controversial [26, 27].

Interestingly, previous findings [28] suggest that patients with lumbar disc herniation (LDH) have more peripheral Th17 cells and enhanced IL-17 expression in blood compared with healthy controls. Some studies also indicate an association between genetic variability in genes encoding interleukin 1 (IL-1α), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and the human leukocyte antigen II (HLA II) regarding persistent LRP [29–33]. Hence, back pain after disc herniation seems to be associated with activation of the immune system.

From a clinical point of view, slow recovery is a major challenge in LRP – the disability is worse and the recovery is slower for LRP than for LBP. Still, previous reviews have only addressed the relationship between genetic variability and LBP. In the present study, however, we provide an overview of the literature addressing genetic factors and biomarkers predicting pain recovery in LRP patients. The present review emphasizes that several genetic factors and biomarkers described in the literature may predict slow recovery in LRP.

Methods

Search strategy

The Medline OVID, Embase, PsycInfo and Web of Science were searched using optimized systematic search strategies including mesh words with explore and a combination of words in the title or abstract related to different expressions of Lumbar radicular pain, Genetic variation and Pain biomarkers. The main key words for the search included “lumbar radicular pain”, “sciatica”, “pain and lumbar disc herniation”, “pain and lumbar prolapse” OR “lumbar radiculopathy”, AND “genetic variability”, “genetic polymorphism”, “allele”, “haplotype”, “microRNA”, “pain biomarker”, “cytokines”, “chemokines”, “interleukins” OR “interferons”. The search was performed from 2004 up to 12th of January 2015.

Selection of studies

Inclusion criteria were prospective studies, including patients with lumbar radicular pain, and assessing genetic factors or pain biomarkers. Exclusion criteria were non English language, lumbar radicular pain due to tumor, infection or systemic disorders.

Procedure

Based on screening of the titles and abstracts eligible articles for full text reading by two of the authors were identified.

Assessing the quality of the studies

A checklist based on Sanderson et al. [34], QATSO (Quality Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews of Observational studies) [35] and the STROBE statement guidelines (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [36] was used. The checklist compromised seven criteria namely: external validity, sample size, description of sample, follow up rate, appropriate reporting of outcome, adjustment for confounding factors (No = not adjusted for any covariates. Yes = adjusted) and correction for multiple testing. The assessments of the two reviewers were compared. If disagreement a final evaluation of the paper was performed.

Results

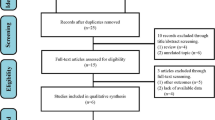

The systematic search identified 880 relevant publications, of which 791 were excluded after screening of titles and abstracts. Thus, 89 studies were found eligible, but after full-text screening only 15 publications met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Methodological quality

A summary of methodological quality is shown in Table 1. External validity found to be satisfactory in 11 of the 15 included studies and number of cases >100 in 10 of the studies. The studies comprise a total of 872 LRP patients and mean age ranged from 41 to 47 years. Seven of the studies emanates from the same patient population that affect the total number of patients included (Table 1). Although all the studies provided a short description of the sample, several shortcomings in this description were identified. Just one study, Karppinen et al. [29], included BMI and work load in the analyzes. Moreover, Gebhardt et al. [37] controlled for smoking and BMI. In only 6 studies the data were evaluated after correction for their multiple testing.

Assessment and definition of pain recovery

All but one study reported VAS (Visual analog scale) as assessment tool for pain. Tegeder et al. [24] did not describe how pain was measured, but provide us the z-score from several time points to express the development in pain intensity over time. Detailed information about pain intensity was not present in most of the included studies. Moreover, we found a variety of different pain descriptions/locations and procedures for pain testing. In two studies, the pain score was based on pain during activity, in two of the studies at rest, whereas in the rest of the studies this was not clearly described. Pain duration at baseline were described in five studies where two reported duration ≥3 months, one study <3 months and the two last both ≥3 and <3 months.

Even if the follow up time was 12 months or more in 12 of the studies, the presentation of the development of pain over time was not clear. Gebhardt et al. [37] measured pain at 12 time points and gave a detailed description of how high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) declined corresponding to decreased pain first 3 weeks, but did not emphasized what happened after the subacute phase.

Pain recovery was described in 4 of the studies. Andrade et al. [38, 39] used >20% reduction in VAS while Rut et al. [40] and Takeuchi et al. [41] used >50% reduction in VAS between baseline and follow to define recovery. Specific description of change in pain state during the follow up period was reported in just two of the studies. Both Olsen et al. [20] and Schistad et al. [30, 42] described a significant decrease in pain the first year after herniation.

Genetic variability and pain recovery

In 9 of the studies the association between genetic variability and LRP were studied (Table 2). The roles of 20 genetic polymorphisms were addressed. Only 1 study addressed the relationship between genetic variability and tissue degeneration seen on MRI.

Olsen et al. [20] and Hasvik et al. [21] demonstrated that a genetic variant, OPRMI rs1799971 SNP, in the gene encoding OPRM1 receptor is associated with both pain and subjective health in LRP patients. The OPRM1 rs1799971 G allele increased the pain score in women, but reduced the pain score in men. Thus, the data revealed a significant interaction between sex and OPRM1 genotype regarding the pain intensity.

Jacobsen et al. [43] showed that the COMT rs4680 SNP affects pain recovery after disk herniation. In both men and women, carriers of COMT rs4680 2G alleles had more pain than carriers of two A alleles at 6 months after disc herniation. Conversely, Rut et al. [40] reported that carriers of two COMT rs4680 G alleles may be associated with significant positive improvement in pain recovery one year after surgery.

Jacobsen et al. [44] addressed the relationship between MMP1 rs1799750 SNP and tissue degeneration. The data indicated that the MMP1 rs1799750, in the gene encoding the MMP1 enzyme, may affect the long-term outcome in disc herniation patients. Carriers of two MMP1 rs1799750 2G alleles had a reduced pain recovery rate, but not increased MRI disc changes.

Moen et al. [31] and Schistad et al. [30, 42] found increased risk of persistent pain in carriers of the IL1α rs1800587 T allele. Moreover, Karppinen et al. [29] demonstrated a significant association between the IL-6 haplotype rs1800797 G/rs1800796 C/rs1800795 C/rs13306435 A and days of leg pain 3 years after disc herniation in men with high physical work load. Finally, Tegeder et al. [24] showed that the GTP cyclohydorlase (GSCH1) haplotype rs8007267 A/rs3783641 T/rs8007201 C/rs752688 A could be protective and be associated with less pain following discectomy.

Six of the studies emanates from the same patient population (Table 1). None of these association studies included data on protein expression.

Biomarkers and pain recovery

Six studies presented data on biomarkers linked to pain recovery (Table 3). As many as 28 biomarkers have been assessed: IL1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL- 10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17, G-CSF, GM-CSF, MCP-1b, MIP-1b, TNFα, TNF R1, TNF R2, CGRP1, Galanin, Neuropeptides4, SubstP. Most of the biomarkers examined are members of the cytokine family, but also the role of some neuropeptides is among the studied molecules. In addition low levels of the C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were assessed in the study by Gebardt et al. 2006 [37].

Andrade et al. [39] was unable to detect any link between Il-6 and pain recovery while Schistad et al. [30, 42] demonstrated from the results that high level of IL-6 correlate with less favorable pain recovery 1 year after disk herniation. Regarding recovery, Andrade et al. [38] and Scuderi et al. [45] found a link to tissue and CSF level of TNFα at one year and tissue IFNα level at 3 month – whereas Takeuchi et al. [41] found that plasma level of the neuropeptide CGRP was associated with the extent of sciatica. In acute lumbosciatic patient, hsCRP declined with decreased pain the first 3 weeks after disc herniation, but no clear relationship between pain and level of hsCRP was observed after that (Gebhardt et al. 2006 [37]). Specific results from the studies assessing biomarkers and pain recovery are listed in Table 3.

Discussion

In the present review, we identified nine studies addressing the relationship between genetic polymorphism and LRP. The data analyzed in these studies were limited to eleven DNA base substitutions. In all these studies, polymorphisms of genes encoding proteins expected to affect the phenotype were studied [46]. Some of the SNPs were located in the promoter region, whereas others were located in the coding regions of the genes.

Two studies reported a positive association between the OPRM1 SNP rs179971 and poor recovery of pain in women with LRP [20, 21]. These data support the previous observation that some individuals, in particular in females, carrying the ORPM1 G allele have increased pain sensitivity [47, 48]. OPRM1 is crucial for processing and modulation of pain. Moreover, several studies addressed the association between COMT SNP rs4680 G allele and pain. This enzyme metabolizes catecholamines and thus modulates adrenergic, noradrenergic and dopaminergic signaling in the CNS as well as in the peripheral tissue. However, while Jacobsen et al. found a positive correlation between the COMT rs4680 G allele and long lasting pain, Rut et al. reported that the same SNP may be associated with better clinical outcome [40, 43].

Although the data may be debated, most experimental studies support a positive correlation between the COMT haplotype rs4680 G, rs6269 A, rs4633 C, rs4818 C and pain hypersensitivity [49]. Moreover, several of these COMT SNPs may be associated with increased postoperative pain. For example, the COMT haplotype rs4680 G, rs6269 A, rs4633 C, rs4818 C is associated with slower recovery after surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative disc disease [50].

Only one study addressed the relationship between genetic variability, tissue degeneration and persistent pain [44]. Previous data suggest that the enzyme MMP influences tissue degradation or inflammation [51]. Surprisingly, however, no relationship between the MMP1 SNP rs1799750 and disc degeneration shown on MRI was observed in the systematic search performed for this review. Still, the study of Jacobsen et al. [44] showed that the MMP1 SNP rs1799750, i.e., the 2G allele insert, may be associated with poor pain recovery after lumbar disc herniation. Previous studies show that other painful degenerative inflammatory conditions may be associated with the MMP1 SNP rs1799750 2G allele [52, 53].

Several lines of evidence suggest that genetic variability in genes encoding inflammatory cytokines may be associated with persistent LBP [16]. The present review shows data that the IL1α rs1800587 T allele and the IL6 haplotype rs180077 G, rs1800796 C, rs1800795 C, rs13306435 A may be associated with slower recovery in LRP patients [29–31]. Moreover, data exists that the rare allele of the gene encoding the GTP cyclohydrolase, could be associated with reduced pain following discectomy in LRP patients [24]. However, more recent reports questions these data [54].

Six studies in the present review show correlations between protein levels and recovery of pain [37–39, 41, 42, 45]. However, only IL-6, TNFα and IFNα seem to be associated with persistence of LRP. Schistad et al. [30, 42] showed that higher serum level of IL-6 predicts a less favorable clinical outcome. Moreover, Scuderi et al. [45] and Andrade et al. [38] showed that TNFα and IFNα may be associated with persistent LRP. In addition, previous studies suggest a correlation between TNFα and recovery of pain in chronic LBP and lumbar radiculopathy patients [55, 56].

Development of persistent pain is multifactorial. It is now well established that psychosocial factors, such as depressive mood, distress and somatization, may contribute to chronic LRP [57]. Together with individual factors as gender, age, smoke, obesity and education level, genetic predisposition may be crucial prognostic factors in LBP patients as well as LRP patients [6, 57].

Strength and limitation

To our knowledge, this is the first paper attempting to provide an overview over genetic variants linked to the development of persistence LRP. Still, many of the findings, including the role of the GTP cyclohydrolase, are controversial and need to be replicated [54]. In addition few researchers present genetic data together with changes in protein expression. In further studies this knowledge gap need to be highlighted.

Therefore, the interpretations of the data, but also the heterogeneity in the nomenclature, might be challenging. In the present review we have listed the genetic variants by number, base substitution, position on DNA and if applicable amino acid substitution. Position of base replacement refers to position found in National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI). The majority of the nucleotide replacements listed is located in the intron or promotor region. Only two of the SNPs cause amino acid substitution. Regarding the interpretation of the data, the link between the genetic variability, protein expression and function is therefore definitely challenging.

External validity in all but one of the genetic association studies is fair. The sample size was >100 patients in nine studies, however, as many as six of the samples emanate from the same cohort, and the methodological quality of the studies may still be debated. A bias towards only positive findings being published cannot be excluded. Moreover, the external validity is poor in the six studies about biomarkers – and in only two studies correction for multiple testing was performed. The strength of this review, however, is the optimized systematic search in several databases and the strict inclusion criteria.

Unfortunately, the studies were too few and too heterogeneous to perform meta-analyses, and many of the studies emanate from the same cohort. Further on, GWAS would shed light on other genetic factors related to the same phenomena. Unfortunately, however, most clinical studies do not have enough statistical strength for GWAS. This may be a major challenge in clinical research. None of the included studies were GWAS. Moreover, no studies addressed the interaction between environmental factors and genetic markers. An extensive systematic review by Eskola et al. 2012 regarding LBP and genetics evaluated that the credibility of reported genetic associations were mostly weak including four of our candidate genes; IL1α, IL1β, IL1RN, MMP1. Finally, each SNP in this review explained just about 1% of the variance. Previous studies show that the explained variance of the SNPs in general is rather low – even for inherited characteristics like human height [58]. Thus, the low explained variance in the present studies underscores the complex mechanisms and multifactorial nature of LRP. Furthermore, the causal relationship between genetic factors and LRP remains to be examined. The clinical value of this review can be questioned but the presented findings may be of importance for better understanding pain mechanism and further research.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that several genetic factors involved in pain perception, inflammation and tissue degeneration may be linked to poor recovery in LRP patients. Further, serum levels of the IL-6, IFNα and TNFα proteins correlate with persistent LRP. The existing literature in this review revealed, however, that many articles are based on the same cohorts; hence the results were generally not replicated in different cohorts. Relatively few candidate genes were examined and the explained variance relatively low. Hence, broader panels of genes and replication of findings across pain cohorts are needed in order to implement these findings in diagnostic procedures and treatment.

Abbreviations

- COMT:

-

Catechol-O-methyltransferase

- hsCRP:

-

High-sensitive C-reactive protein

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- LRP:

-

Lumbar radicular pain

- MMP:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase

- OPRM1:

-

Opioid receptor mu 1

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581–5.

Younes M, Bejia I, Aguir Z, Letaief M, Hassen-Zrour S, Touzi M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of disk-related sciatica in an urban population in Tunisia. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(5):538–42.

Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2007;334(7607):1313–7.

Brage S, Ihlebaek C, Natvig B, Bruusgaard D. Musculoskeletal disorders as causes of sick leave and disability benefits. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2010;130(23):2369–70.

Rubin DI. Epidemiology and risk factors for spine pain. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):353–71.

Miranda H, Viikari-Juntura E, Martikainen R, Takala EP, Riihimaki H. Individual factors, occupational loading, and physical exercise as predictors of sciatic pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(10):1102–9.

Videman T, Levalathi E, Battie MC. The effects of anthropometrics, lifting strength, and physical activities in disc degeneration. Spine. 2007;32(13):1406–13.

Bogduk N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012;50(4):613–28.

Haugen AJ, Brox JI, Grovle L, Keller A, Natvig B, Soldal D, et al. Prognostic factors for non-success in patients with sciatica and disc herniation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:183.

Ala-Kokko L. Genetic risk factors for lumbar disc disease. Ann Med. 2002;34(1):42–7.

Sambrook PN, MacGregor AJ, Spector TD. Genetic influences on cervical and lumbar disc degeneration: a magnetic resonance imaging study in twins. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(2):366–72.

Kim WH, Lee SH, Lee DY. Changes in the cross-sectional area of multifidus and psoas in unilateral sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50(3):201–4.

Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009;147(1-3):17–9.

Olmarker K, Rydevik B, Nordborg C. Autologous nucleus pulposus induces neurophysiologic and histologic changes in porcine cauda equina nerve roots. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18(11):1425–32.

Skouen JS, Brisby H, Otani K, Olmarker K, Rosengren L, Rydevik B. Protein markers in cerebrospinal fluid in experimental nerve root injury. A study of slow-onset chronic compression effects or the biochemical effects of nucleus pulposus on sacral nerve roots. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(21):2195–200.

Tegeder I, Lotsch J. Current evidence for a modulation of low back pain by human genetic variants. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(8B):1605–19.

Zubieta JK, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, et al. Regional mu opioid receptor regulation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Science. 2001;293(5528):311–5.

Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu K, Xu Y, et al. COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science. 2003;299(5610):1240–3.

Zubieta JK, Bueller JA, Jackson LR, Scott DJ, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, et al. Placebo effects mediated by endogenous opioid activity on mu-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25(34):7754–62.

Olsen MB, Jacobsen LM, Schistad EI, Pedersen LM, Rygh LJ, Roe C, et al. Pain intensity the first year after lumbar disc herniation is associated with the A118G polymorphism in the opioid receptor mu 1 gene: evidence of a sex and genotype interaction. J Neurosci. 2012;32(29):9831–4.

Hasvik E, Iordanova Schistad E, Grovle L, Julsrud Haugen A, Roe C, Gjerstad J. Subjective health complaints in patients with lumbar radicular pain and disc herniation are associated with a sex - OPRM1 A118G polymorphism interaction: A prospective 1-year observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:161.

Diatchenko L, Fillingim RB, Smith SB, Maixner W. The phenotypic and genetic signatures of common musculoskeletal pain conditions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(6):340–50.

Reimann F, Cox JJ, Belfer I, Diatchenko L, Zaykin DV, McHale DP, et al. Pain perception is altered by a nucleotide polymorphism in SCN9A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(11):5148–53.

Tegeder I, Costigan M, Griffin RS, Abele A, Belfer I, Schmidt H, et al. GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin regulate pain sensitivity and persistence. Nat Med. 2006;12(11):1269–77.

Rathod TN, Chandanwale AS, Gujrathi S, Patil V, Chavan SA, Shah MN. Association between single nucleotide polymorphism in collagen IX and intervertebral disc disease in the Indian population. Indian J Orthop. 2012;46(4):420–6.

Voscopoulos C, Lema M. When does acute pain become chronic? Br J Anaesth. 2010;105 Suppl 1:i69–85.

Haldeman S. North American Spine Society: failure of the pathology model to predict back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(7):718–24.

Cheng L, Fan W, Liu B, Wang X, Nie L. Th17 lymphocyte levels are higher in patients with ruptured than non-ruptured lumbar discs, and are correlated with pain intensity. Injury. 2013;44(12):1805–10.

Karppinen J, Daavittila I, Noponen N, Haapea M, Taimela S, Vanharanta H, et al. Is the interleukin-6 haplotype a prognostic factor for sciatica? Eur J Pain. 2008;12(8):1018–25.

Schistad EI, Jacobsen LM, Roe C, Gjerstad J. The interleukin-1alpha gene C > T polymorphism rs1800587 is associated with increased pain intensity and decreased pressure pain thresholds in patients with lumbar radicular pain. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(10):869–74.

Moen A, Schistad EI, Rygh LJ, Roe C, Gjerstad J. Role of IL1A rs1800587, IL1B rs1143627 and IL1RN rs2234677 genotype regarding development of chronic lumbar radicular pain; a prospective one-year study. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2014;9(9):e107301.

Dominguez CA, Kalliomaki M, Gunnarsson U, Moen A, Sandblom G, Kockum I, et al. The DQB1*03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation. Pain. 2013;154(3):427–33.

Noponen-Hietala N, Virtanen I, Karttunen R, Schwenke S, Jakkula E, Li H, et al. Genetic variations in IL6 associate with intervertebral disc disease characterized by sciatica. Pain. 2005;114(1-2):186–94.

Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666–76.

Wong WC, Cheung CS, Hart GJ. Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2008;5:23.

Meerpohl JJ, Blumle A, Antes G, Elm E. Reporting guidelines are also useful for readers of medical research publications: CONSORT, STARD, STROBE and others. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2009;134(41):2078–83.

Gebhardt K, Brenner H, Sturmer T, Raum E, Richter W, Schiltenwolf M, et al. The course of high-sensitive C-reactive protein in correlation with pain and clinical function in patients with acute lumbosciatic pain and chronic low back pain - A 6 months prospective longitudinal study. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(8):711–9.

Andrade P, Visser-Vandewalle V, Philippens M, Daemen MA, Steinbusch HW, Buurman WA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels correlate with postoperative pain severity in lumbar disc hernia patients: opposite clinical effects between tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2. Pain. 2011;152(11):2645–52.

Andrade P, Hoogland G, Garcia MA, Steinbusch HW, Daemen MA, Visser-Vandewalle V. Elevated IL-1beta and IL-6 levels in lumbar herniated discs in patients with sciatic pain. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(4):714–20.

Rut M, Machoy-Mokrzynska A, Reclawowicz D, Sloniewski P, Kurzawski M, Drozdzik M, et al. Influence of variation in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene on the clinical outcome after lumbar spine surgery for one-level symptomatic disc disease: a report on 176 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014;156(2):245–52.

Takeuchi H, Kawaguchi S, Ohwada O, Kobayashi H, Hayakawa M, Takebayashi T, et al. Plasma neuropeptides in patients undergoing lumbar discectomy. Spine. 2007;32(2):E79–84.

Schistad EI, Espeland A, Pedersen LM, Sandvik L, Gjerstad J, Roe C. Association between baseline IL-6 and 1-year recovery in lumbar radicular pain. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(10):1394–401.

Jacobsen LM, Schistad EI, Storesund A, Pedersen LM, Rygh LJ, Roe C, et al. The COMT rs4680 Met allele contributes to long-lasting low back pain, sciatica and disability after lumbar disc herniation. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(7):1064–9.

Jacobsen LM, Schistad EI, Storesund A, Pedersen LM, Espeland A, Rygh LJ, et al. The MMP1 rs1799750 2G allele is associated with increased low back pain, sciatica, and disability after lumbar disk herniation. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(11):967–71.

Scuderi GJ, Cuellar JM, Cuellar VG, Yeomans DC, Carragee EJ, Angst MS. Epidural interferon gamma-immunoreactivity: a biomarker for lumbar nerve root irritation. Spine. 2009;34(21):2311–7.

Fillingim RB, Wallace MR, Herbstman DM, Ribeiro-Dasilva M, Staud R. Genetic contributions to pain: a review of findings in humans. Oral Dis. 2008;14(8):673–82.

Tan EC, Lim EC, Teo YY, Lim Y, Law HY, Sia AT. Ethnicity and OPRM variant independently predict pain perception and patient-controlled analgesia usage for post-operative pain. Mol Pain. 2009;5:32.

Sia AT, Lim Y, Lim EC, Goh RW, Law HY, Landau R, et al. A118G single nucleotide polymorphism of human mu-opioid receptor gene influences pain perception and patient-controlled intravenous morphine consumption after intrathecal morphine for postcesarean analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(3):520–6.

Diatchenko L, Nackley AG, Slade GD, Bhalang K, Belfer I, Max MB, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms are associated with multiple pain-evoking stimuli. Pain. 2006;125(3):216–24.

Dai F, Belfer I, Schwartz CE, Banco R, Martha JF, Tighioughart H, et al. Association of catechol-O-methyltransferase genetic variants with outcome in patients undergoing surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative disc disease. Spine J. 2010;10(11):949–57.

Zawilla NH, Darweesh H, Mansour N, Helal S, Taha FM, Awadallah M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-3, vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, and occupational risk factors in lumbar disc degeneration. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(2):370–81.

Planello AC, Campos MI, Meloto CB, Secolin R, Rizatti-Barbosa CM, Line SR, et al. Association of matrix metalloproteinase gene polymorphism with temporomandibular joint degeneration. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(1):1–6.

de Souza AP, Trevilatto PC, Scarel-Caminaga RM, Brito RB, Line SR. MMP-1 promoter polymorphism: association with chronic periodontitis severity in a Brazilian population. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(2):154–8.

Kim H, Dionne RA. Lack of influence of GTP cyclohydrolase gene (GCH1) variations on pain sensitivity in humans. Mol Pain. 2007;3:6.

Wang H, Schiltenwolf M, Buchner M. The role of TNF-alpha in patients with chronic low back pain-a prospective comparative longitudinal study. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):273–8.

Genevay S, Finckh A, Payer M, Mezin F, Tessitore E, Gabay C, et al. Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in periradicular fat tissue in patients with radiculopathy from herniated disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(19):2041–6.

Manek NJ, MacGregor AJ. Epidemiology of back disorders: prevalence, risk factors, and prognosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(2):134–40.

Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467(7317):832–8.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Hilde I. Flaatten, librarian, for excellent support and advice in the process of systematic search for articles.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting our findings is contained within the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

SB, JG and CR were involved in the design of the review paper. SB performed the systematic search for articles. SB and CR performed reading, assessed and included the relevant articles, assessed methodological quality and analyzed the results. SB, AM, ES, JG and CR participated in interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. SB, JG and CR wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and stand by the integrity of the entire work. We declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ information

No additional comments.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable as this is a systematic review of previously published studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bjorland, S., Moen, A., Schistad, E. et al. Genes associated with persistent lumbar radicular pain; a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17, 500 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1356-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1356-5