Abstract

Background

Glenohumeral instability is a common problem following traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation. Two major risk factors of recurrent instability are glenoid and Hill-Sachs bone loss. Higher failure rates of arthroscopic Bankart repairs are associated with larger degrees of bone loss; therefore it is important to accurately and reliably quantify glenohumeral bone loss pre-operatively. This may be done with radiography, CT, or MRI; however no gold standard modality or method has been determined. A scoping review of the literature was performed to identify imaging methods for quantifying glenohumeral bone loss.

Methods

The scoping review was systematic in approach using a comprehensive search strategy and standardized study selection and evaluation. MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched. Initial selection included articles from January 2000 until July 2013, and was based on the review of titles and abstracts. Articles were carried forward if either reviewer thought that the study was appropriate. Final study selection was based on full text review based on pre-specified criteria. Consensus was reached for final article inclusion through discussion amongst the investigators. One reviewer extracted data while a second reviewer independently assessed data extraction for discrepancies.

Results

Forty-one studies evaluating glenoid and/or Hill-Sachs bone loss were included: 32 studies evaluated glenoid bone loss while 11 studies evaluated humeral head bone loss. Radiography was useful as a screening tool but not to quantify glenoid bone loss. CT was most accurate but necessitates radiation exposure. The Pico Method and Glenoid Index method were the most accurate and reliable methods for quantifying glenoid bone loss, particularly when using three-dimensional CT (3DCT). Radiography and CT have been used to quantify Hill-Sachs bone loss, but have not been studied as extensively as glenoid bone loss.

Conclusions

Radiography can be used for screening patients for significant glenoid bone loss. CT imaging, using the Glenoid Index or Pico Method, has good evidence for accurate quantification of glenoid bone loss. There is limited evidence to guide imaging of Hill-Sachs bone loss. As a consensus has not been reached, further study will help to clarify the best imaging modality and method for quantifying glenohumeral bone loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glenohumeral instability (GHI) has been associated with a recurrence rate ranging from 30-90 % [1–3]. Currently, arthroscopic Bankart repair using modern suture anchor techniques have failure rates ranging from 4-17 % [4–6]. A number of risk factors have been proposed to predict recurrence of GHI following arthroscopic Bankart repair including: age, humeral head and glenoid bone loss, shoulder hyperlaxity, and contact activity [1, 7–10]. Glenoid bone loss occurs in up to 90 % of patients with recurrent GHI [11] and, on average, occurs nearly parallel to the long axis of the glenoid (03:01–03:20 on a clock face) [12, 13]. Burkhart et al. showed that significant glenoid bone loss, approximately 25-45 % of glenoid width loss, was associated with higher failure rates of arthroscopic Bankart repairs [14, 15]. The critical defect size for predicting failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs has been explored biomechanically [16–18]. Yamamoto et al. found that glenoid loss greater than 20 % glenoid length and 26 % of glenoid width, destabilized the shoulder [19]. The threshold of glenoid bone loss above which arthroscopic Bankart repairs may fail has generally been accepted as glenoid width loss ≥25 %, which is equivalent to ≥19 % of the glenoid length and ≥20 % of the surface area created by a best-fit circle on the inferior surface of the glenoid [14–20]. Width loss of 25 % may be expressed as a millimeter defect, varying based on individual glenoid anatomy but is approximately 6-8 mm given that the average glenoid width at the level of the bare area is 24-26 mm [19, 21]. It is important to keep in mind how one calculates glenoid bone loss, as the threshold for surface area is different than for glenoid width.

Humeral head bone loss, also known as a Hill-Sachs lesion, occurs in up to 93 % of patients with recurrent GHI [22]. Hill-Sachs lesions are oriented in the axial plane approximately at 07:58+/−00:48 or at an angle of 239.1+/−24.3 ° from 12 o’clock [23]. In a biomechanical study, Kaar et al. showed that defects created at an orientation of 209 ° significantly decreased resistance to dislocation when they were greater than 5/8 the depth of the radius of the humeral head in the axial plane [24]. Sekiya et al. demonstrated that Hill-Sachs lesions created in a posterolateral orientation benefited from allograft transplantation when greater than 37.5 % of the humeral head diameter [25]. In a later cadaveric study, Sekiya et al. showed that defects of 25 % of the humeral head diameter in isolation did not increase risk of dislocation following a capsulolabral repair [26]. There is a relationship between recurrent dislocations and failure of arthroscopic Bankart repair with increasing size of the Hill-Sachs lesion, although an accepted threshold value for Hill-Sachs bone loss has not yet been determined [9, 27, 28]. Hill-Sachs bone loss occurs simultaneously with glenoid bone loss in up to 62 % of GHI patients [29]. The way in which the glenoid and Hill-Sachs lesions interact and contribute to GHI is complex but does appear to be synergistic [30].

The degree of glenohumeral bone loss plays a role in surgical decision-making. The glenoid lesion may be treated successfully with an arthroscopic Bankart repair if it is smaller than the previously mentioned values. Larger glenoid bone lesions may require a bone augmentation procedure such as a Latarjet coracoid transfer or a J-graft procedure (bone graft harvested from iliac crest) [31]. A large Hill-Sachs defect can be addressed via a remplissage procedure (posterior capsulodesis and infraspinatus tenodesis), allograft, resurfacing arthroplasty, or rotational osteotomy. Ideally, the surgeon would be able to accurately quantify bone loss preoperatively to best ensure a successful post-operative outcome with the lowest rate of recurrent instability and the least amount of post-surgical morbidity.

Multiple imaging methods exist for quantifying glenoid and Hill-Sachs bone loss including radiography, computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Radiography is inexpensive and easy to obtain but may be less accurate in detecting the presence of bone lesions compared to CT. Radiographic methods have been proposed using both basic views (true AP, axillary) and special views (Bernageau profile) to measure glenoid and Hill-Sachs bone loss. CT is easy to obtain and accurate with respect to bony detail, but necessitates radiation exposure. MRI is expensive and more difficult to obtain in public health care systems but has no radiation exposure, and may provide information on associated soft tissue lesions involving the labrum, rotator cuff, and capsule. However, assessment of bone lesions may be inferior to that of CT. Two common methods of calculating glenoid bone loss using CT and MRI are width measurements such as the Griffiths Index (Fig. 1) and best-fit circle surface area measurements such as the Pico Method (Fig. 2) [32, 33]. These methods involve reformatting to subtract the humeral head and get an en face view of the glenoid. The inferior 2/3 of the glenoid approximates a true circle, the size of which can be estimated based on either the contralateral glenoid or intact posteroinferior margins of the injured glenoid [11, 34, 35]. Bone loss can then be expressed as the area lost from the circle or the anterior-to-posterior width loss. Determination for Hill-Sachs bone loss has included, among others, depth, width, and length measurements [36–39].

Griffith Index. Width measurements are made perpendicular to a line through the vertical axis of the glenoid and compared to the uninjured glenoid (B/A x 100) to determine percent width loss (adapted from Griffith et al. [33])

Pico Method. The original description of Pico Method involved determining the circumference of the contralateral, normal inferior glenoid circle based on the intact 3–9 o’clock margin, transferring the circle to the injured glenoid, and manually tracing out the glenoid defect and using software to calculate surface area bone loss. Note that the Pico Method has also been used with the intact 6 o’clock-9 o’clock postero-inferior margin of the injured glenoid to determine the pre-injury glenoid circle (adapted from Bois et al. [63])

The degree of glenohumeral bone loss affects the success of arthroscopic Bankart repair and, at present, there is no consensus on a gold standard imaging method or modality for the quantification of glenohumeral bone loss. We performed a scoping review of the literature to identify current published imaging methods for quantifying glenoid and humeral head bone loss in GHI and to evaluate if there was a gold standard method and modality supported by evidence.

Methods

Study design

A scoping review was performed to evaluate the literature based on established guidelines [40, 41]. Scoping reviews are designed to assess the extent of a body of literature and identify knowledge gaps. Although qualitative in nature, the review can be systematic in approach through a comprehensive search strategy and standardized study selection and evaluation, as in our study. Due to heterogeneity in the articles reviewed, no meta-analyses were performed in this study.

Selection criteria

Studies were included if the following conditions were met: (1) publication after the year 2000 (following a preliminary review of the literature, the majority of relevant imaging methods were published after this time point; publications prior to 2000 are included in our introduction and discussion when historically relevant); (2) use of human or cadaveric human subjects; (3) evaluation of imaging methods including radiography, CT, and/or MRI; and (4) quantification of glenoid or Hill-Sachs bone loss using these imaging modalities. Criteria for exclusion were: (1) non-English language; and (2) publication in the form of an abstract, letter, or review article.

Search strategies

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from January 2000 until July 2013. A search algorithm was created with the guidance of a medical librarian (see Additional file 1).

Study selection

Article selection was performed over two rounds, by two orthopaedic surgery residents with the assistance of two upper extremity fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeons. During the first round, selection was based on the review of titles and abstracts. To be as inclusive as possible, an article was carried forward to the next stage if either reviewer thought that the study was appropriate. Final study selection was based on full text review using the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Duplicate studies were kept until the final article selection. Consensus was reached for final article inclusion through discussion amongst the investigators.

Data extraction

One reviewer extracted study design, imaging modality evaluated, patient characteristics, quantification method used, and findings. A second reviewer independently assessed data extraction for any discrepancies. When provided by the authors, the reliability, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity are presented in the results section with accompanying tables.

Results

Article selection

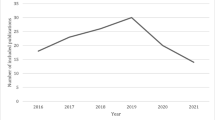

Initial literature search retrieved 4536 total articles: 1462 from MEDLINE, 1560 from EMBASE, 827 from Scopus, and 687 from Web of Science (Fig. 3). After the initial review of titles and abstracts, 212 articles were retained. Following review of the full text, 114 articles remained. After the removal of duplicates, 41 articles were included.

Article summary

Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 summarize the selected articles. We retained 11 articles focusing on Hill-Sachs bone loss, 32 for glenoid bone loss, and 2 articles evaluated both. There were a significantly higher number of articles evaluating CT imaging (38) compared to radiography (11) and MRI (10). For glenoid bone loss, radiography was evaluated in 7 studies [18, 42–47], MRI in 8 studies [21, 42, 44, 48–53], and CT in 32 studies [11, 18, 20, 21, 32, 33, 35, 42–51, 54–69]. For Hill-Sachs bone loss, radiography was evaluated in 5 studies [37–39, 46, 47], MRI in 2 studies [70, 71], and CT in 5 studies [23, 36, 72–74].

Glenoid imaging

Radiography

Routine radiographic views (true AP and axillary) were found to have lower accuracy and reliability in calculating glenoid bone loss (Table 1) [18, 42, 44, 45, 47]. Special radiographic views on the other hand, in particular the Bernageau profile view (Fig. 4), had better accuracy and reliability scores [18, 43, 46]. The Bernageau profile had an intra-observer intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 0.897-0.965 and inter-observer ICC 0.76-0.81 compared to a true AP radiograph with an intra-observer ICC 0.66-0.93 and inter-observer ICC 0.44-0.47 [43, 47]. Sommaire et al. demonstrated failure of Bankart repair when the width loss was 5.3 % compared to no failure with width loss 4.2 % using the Bernageau view (p = 0.003), although no clinically relevant threshold was defined [46]. A true AP radiograph was found to be specific (100 %) but not sensitive (54-65 %) for detecting a large glenoid bone lesion [45].

Bernageau Radiography. a) Patient positioning. b) Antero-posterior glenoid width measurement on this view (Murachovsky et al. [43])

CT and MRI

Surface area loss measurements

The surface area loss methods vary in the manner to which a circle is approximated to the inferior glenoid - based on either contralateral glenoid or intact posteroinferior margins of injured glenoid - but will be grouped together in this review as best-fit circle surface area methods (Fig. 10) (BCSA). The Pico Method (Fig. 2) is a BCSA based on the contralateral glenoid described by Baudi et al. [75]. The Pico Method has demonstrated good inter-observer (ICC 0.90) and intra-observer (ICC 0.94, 0.96-1.0) reliability as well as a low coefficient of variation (2.2-2.5 %) [32, 60, 65]. Magarelli et al. (mean difference between two-dimensional CT [2DCT] and three-dimensional CT [3DCT] 0.62 %+/−1.96 %) showed the method could be applied accurately with both 2DCT and 3DCT [32]. The previous article used software to calculate the surface area lost, but Barchillon et al. demonstrated that a BCSA method similar to the Pico Method could be applied using 3DCT, a femoral head gauge, and applying a mathematical formula [20]. Milano et al. demonstrated that using the Pico Method, recurrent dislocation was associated with defects greater than 20 %. [55] Huijsmans et al. showed that a BCSA method could be used by MRI with similar accuracy to 3DCT [21]. Nofsinger et al. used a method termed the Anatomic Glenoid Index (see Table 2 for description) in an attempt to retrospectively predict which surgical procedure an instability patient would receive but were unable to separate the two groups with their method [35].

Width loss measurements

Griffith et al. created the Griffith Index using bilateral shoulder CT scans (Fig. 1) as one of the first width loss techniques and it has been found to be reliable and accurate [33, 47, 58]. A method similar to the Griffith Index, termed the Glenoid Index (Fig. 5) was shown to accurately predict if a patient would require a Latarjet procedure 96 % of the time [68]. Other width loss measurement methods have measured width loss from a circle approximated to the inferior glenoid (based on either contralateral or ipsilateral glenoid) and have been found to have good reliability and accuracy (Table 3) [47, 48, 50, 52]. Evidence is conflicting with respect to whether width loss measurements can be applied to MRI. Tian et al. suggested volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination (VIBE) magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) was as accurate as 2DCT and Lee et al. found a correlation between 2DCT and MRI of r = 0.83 and the difference in accuracy was 1.3 % for width loss measurements [51, 52]. Moroder et al. found that MRI (35 % sensitive, 100 % specific) was not as sensitive as 3DCT (100 % sensitive, 100 % specific) for detecting a significant bone lesion [50]. Gyftopoulous et al. found 3DCT was more accurate than 2DCT and MRI (percent error 3DCT 2.17-3.5 %, 2DCT 2.22-17.1 %, MRI 2.06-5.94 %) although the difference was not significant and they concluded that MRI could accurately measure glenoid bone loss [48].

Glenoid Index. The Glenoid Index is calculated from injured width/normal width. Chuang et al. use the parameters of the normal glenoid to normalize the pre-injury glenoid width accounting for any height difference between shoulders. They then compare the ratio of post-injury width to pre-injury width. Although demonstrated here using 2D CT, the description of the Glenoid Index by Chuang et al. involves 3DCT. (Adapted from Chuang et al. [68])

Comparative studies

A few studies directly compared imaging modalities and methods (Table 4). Bishop et al. found 3DCT had the highest accuracy (agreement kappa 0.5) and second highest intra-observer reliability (intra-observer kappa 0.59) while radiography (agreement kappa 0.15, intra-observer kappa 0.45) had the lowest in a comparison of radiography, 2DCT, 3DCT, and MRI [42]. Rerko et al. also found that 3DCT was the most accurate (percent error [PE] -3.3 % +/− 6.6 %) and reliable (inter-observer ICC 0.87-0.93) method compared to radiography (PE −6.9 %; ICC 0.12-0.53), 2DCT (PE −3.7 %; ICC 0.82-0.89), and MRI (PE −2.75 %; ICC 0.38-0.85) [44]. Bois et al. evaluated 7 measurement techniques using 2DCT and 3DCT and found that the Pico Method based on the contralateral, intact glenoid (inter-observer ICC 0.84; PE 7.32) and Glenoid Index using 3DCT (ICC 0.69; PE 0.01) were the most reliable and accurate methods [63].

Other glenoid bone loss methods

Results are presented in Table 5. Dumont et al. used an arc angle to determine percent surface area loss but have not tested the method clinically [49]. De Filipo et al. created a new technique using curved multiplanar reconstruction (MPR), a CT technique generally used for vascular studies for its ability to follow curved surfaces, and found it was more accurate than flat MPR in measuring surface area loss (Fig. 6) [66]. Diederichs et al. expressed bone loss in terms of volume using 3D computer software to mirror the contralateral normal glenoid and found good accuracy in a cadaveric study [59]. Sommaire et al. used Gerber’s Index and found that a threshold of 40 % bone loss was associated with recurrent instability (Fig. 7) [46].

Gerber Index. The Gerber Index calculates bone loss based on a ratio of length of glenoid defect and diameter of glenoid. (Adapted from Sommaire et al. [46])

Hill-Sachs imaging

Radiography

Results are presented in (Table 6). Ito et al. positioned patients supine with the shoulder in 135 ° flexion and 15 ° of internal rotation to obtain a view of the posterolateral notch and calculate depth and width of the Hill-Sachs lesion but reliability was not explored [38]. Kralinger et al. calculated a Hill-Sachs Quotient (Fig. 8) by measuring depth and width on a true AP radiograph with the arm in 60 ° internal rotation and length on a Bernageau profile [39]. Recurrence rate was noted to be higher with a larger quotient (Grade I 23.3 %; grade II 16.2 %; grade III 66.7 %) although the reliability and accuracy have not been tested.

Hill-Sachs Quotient. a) True AP x-ray of the humerus with the shoulder in 60° internal rotation to measure the width (x) and depth (y) of the lesion. b) Bernageau profile view to measure the length (z) of the lesion. The Hill-Sachs Quotient is calculated by multiplying x, y and z. Grade: I <1.5 cm2; II 1.5-2.5 cm2; III > 2.5 cm2 (Adapted from Kralinger et al. [39])

A technique of creating a ratio using the Hill-Sachs defect depth and humeral head radius (d/R) on a true AP radiograph with the arm in internal rotation has been found to be reliable and clinically relevant (Fig. 9). Charousset et al. demonstrated inter- and intra-observer reliability ICC 0.81-0.92 and 0.72-0.97 respectively with this technique [47]. Sommaire et al. retrospectively found the recurrence rate of GHI was 40 % when d/R >20 % compared to 9.6 % when d/R <20 %, while Hardy et al. found arthroscopic stabilization failure rate was 56 % when d/R > 15 % compared to 16 % when d/R <15 % [37, 46].

Humeral head depth:radius ratio (d/R). On a true AP x-ray with internal rotation, a circle template is fit to the contour of the articular surface of the humeral head and the depth of Hill-Sachs bone loss is measured. (Adapted from Sommaire et al. [46])

CT and MRI

Hardy et al. measured the volume of the defect on axial slices using width, depth, and length and found a significantly larger defect volume in patients with lower Duplay functional scores but did not evaluate reliability [37]. Saito et al. and Cho et al. both measured defect depth and width on the axial slice where the lesion was largest [23, 36]. Saito et al. found intra-observer Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.954-0.998 using 2DCT. Cho et al. found inter- and intra-observer reliability ICC of 0.772-0.996 and 0.916-0.999 respectively for depth and width measurements on 2DCT. Cho et al. also showed that the size of engaging Hill-Sachs lesions were significantly larger than non-engaging lesions. Kodali et al. evaluated the reliability and accuracy of 2DCT with an anatomic model and showed inter-observer reliability ICC 0.721 and 0.879 for width and depth respectively. The accuracy was highest in axial slices but there was still a percent error of 13.6+/−8.4 % [72].

Two studies evaluated MRI for quantifying Hill-Sachs lesions. Salomonsson et al. measured the depth of the lesion but were not able to show a significant difference between stable and unstable shoulders that were treated non-operatively [71]. Kirkley et al. tested the agreement between MRI and arthroscopy for the quantification of Hill-Sachs size [70]. They showed moderate agreement (Cohen’s kappa value 0.444) for the size of the lesion as normal, less than 1 cm, or greater than 1 cm.

Discussion

Glenohumeral bone loss is a key factor in predicting recurrent instability following traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation. Increasing size of glenoid and Hill-Sachs lesions are associated with higher failure rates of arthroscopic Bankart repairs. Clinical and biomechanical studies have attempted to determine threshold values of glenohumeral bone loss to use in preoperative planning. Radiography, CT, and MRI have all been explored as imaging modalities for quantification of these glenohumeral bone lesions, with CT being studied most extensively. Within each modality a number of methods have been proposed to quantify the bone loss. There is still a need for further investigation to determine the best modality and method but significant progress has been made since 2000.

Radiography appears to have a role in screening patients for glenoid bone loss; standard radiographic views are straightforward for imaging technicians to obtain but their accuracy is low compared to CT and MRI [42]. Specialized radiographic views are more accurate; however they may be difficult to reproduce clinically due to patient discomfort or apprehension [74]. Slight deviations in gantry orientation or arm positioning may also obscure the bony details [47].

Two general methods emerged when quantifying glenoid bone loss using advanced imaging, width and surface area methods. Each of these methods uses humeral head subtraction and reconstruction to obtain en face views of the glenoid. Because bone loss occurs anteriorly, width methods measure the bone loss in this anterior-posterior dimension in the inferior 2/3 of the glenoid. Ji et al. state that this measurement should be made specifically at 03:20 on a clock face, the most common location of bone loss [13]. The bone loss in the width methods is expressed compared to the pre-injury glenoid. Some authors have used CT scans of the contralateral, uninjured shoulder to obtain the pre-injury width. Others have approximated the pre-injury width by using the intact inferior edges of the injured glenoid to place a circle. Earlier studies suggested that either form of calculating the width loss was adequate, although newer studies have found that using bilateral CT is more accurate [42, 63]. The Glenoid Index (Fig. 5) is the most accurate width measurement method. Surface area methods function by approximating a circle to the inferior glenoid in the same manner as the width methods then finding the area missing. The surface area methods have been studied frequently and have good to excellent reliability [32, 60, 65]. Initially computer software was required to calculate the surface area; however Barchillon et al. showed that one could use a femoral gauge in a clinical setting and still produce accurate results [20]. Comparative studies suggest that the Pico Method based on bilateral CT scans is most accurate and reliable, particularly when using 3DCT versus 2DCT [42, 48, 63]. The accuracy of the Pico method may be affected in part due to the curved nature and concavity of the glenoid. De Felippo et al. have attempted to address this with their De Felippo method that utilizes curved MPR. This was shown to have low interobserver variability and a high correlation with their reference standard. Evidence is currently equivocal if MRI can be used to calculate glenoid bone loss using width and surface area methods in a clinical setting [48, 50, 61]. In comparative studies, CT was found to be more accurate than MRI [42, 48].

Radiography has been shown to be useful in quantifying Hill-Sachs bone loss. Creating a depth/radius ratio on a true AP radiograph with internal rotation is reliable and shown to be clinically relevant, although the accuracy has not been clarified [37, 46, 47]. CT imaging has been used to quantify depth, width, and volume of the lesion. It appears the reliability of CT is good but its accuracy is questionable, often underestimating the size of the lesion [72]. A complicating factor in determining the significance of a Hill-Sachs lesion is the role its orientation plays. More horizontal lesions tend to engage the glenoid lesion and incorporating this factor along with the size is likely important but has not been determined yet [36]. Walia et al. have explored how Hill-Sachs and glenoid lesions interact and engage theoretically and concluded that combined bony defects reduced stability more than expected based on isolated defects alone [30]. The exact way they reduce stability and how to calculate this clinically is unknown.

This study is limited by its qualitative nature. Because the literature has evaluated multiple methods and modalities with different statistical tools it is difficult to pool data and achieve a clear answer of which method is the best. However, this may guide future prospective studies into which method to apply. There was a trend to use either a width or surface-area method, each of which can be applied with the same imaging data set obtained from a CT or MRI. Comparing these methods and correlating with surgical results may give an answer to the best imaging method.

Conclusions

Our scoping review has synthesized the current evidence regarding imaging techniques to quantify glenoid and Hill-Sachs bone loss. A number of modalities and methods have been explored to quantify glenoid bone loss. Radiography does not appear to have the accuracy required for pre-operative planning but may play a role in screening patients that would require advanced imaging. The Bernageau profile view to calculate AP glenoid width is the most accurate radiograph. CT is the most accurate modality but the risk of radiation exposure, particularly when using methods that require bilateral imaging, needs to be considered. Of the methods used with CT, the Glenoid Index is the most accurate and reliable width method while the Pico Method is the most accurate and reliable surface area method. The Glenoid Index requires bilateral shoulder CT and the Pico Method is most accurate when applied using bilateral CT but may also be applied with unilateral imaging. There are equivocal findings about the accuracy or MRI compared to CT and this needs to be clarified by future studies.

A consensus measurement technique for calculating Hill-Sachs bone loss or a threshold size for predicting recurrent instability has not yet been established. Larger lesions, at least >25 % of the humeral head diameter, appear to increase risk of recurrent instability in biomechanical studies [24]. Calculating a depth:radius radio on a true AP radiograph with the arm internally rotated is inexpensive, easy to obtain, and predicts recurrence with good reliability when >20 %. However, its accuracy has not yet been established. Measuring the depth and width on axial slices of a CT scan have good to excellent reliability and have been associated with engaging Hill-Sachs lesions. However the role of CT in predicting recurrence has not been determined.

Ease of calculation, radiation exposure, experience of interpreting radiologist or surgeon, and software availability are factors that should be considered when determining which method will be used. Finally, glenoid and Hill-Sachs bone loss may need to be evaluated together as the manner in which these lesions interact is complex and requires further study.

Abbreviations

- 2DCT:

-

Two-dimensional computed tomography

- 3DCT:

-

Three-dimensional computed tomography

- BCSA:

-

Best-fit circle surface area

- d/R:

-

Hill Sachs defect depth and humeral head radius

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GHI:

-

Glenohumeral instability

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- MPR:

-

Multiplanar reconstruction

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance arthrography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PE:

-

Percentage error

- VIBE:

-

Volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination

References

Hovelius L, Olofsson A, Sandstrom B, et al. Nonoperative treatment of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in patients forty years of age and younger. a prospective twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:945–52.

Mclaughlin HL, Cavallaro WU. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Am J Surg. 1950;80:615–21.

Simonet WT, Cofield RH. Prognosis in anterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:19–24.

Hobby J, Griffin D, Dunbar M, Boileau P. Is arthroscopic surgery for stabilisation of chronic shoulder instability as effective as open surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 62 studies including 3044 arthroscopic operations. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2007;89:1188–96.

Voos JE, Livermore RW, Feeley BT, et al. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic bankart repairs for anterior instability. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:302–7.

Ide J, Maeda S, Takagi K. Arthroscopic bankart repair using suture anchors in athletes: Patient selection and postoperative sports activity. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1899–905.

Flinkkila T, Hyvonen P, Ohtonen P, Leppilahti J. Arthroscopic bankart repair: Results and risk factors of recurrence of instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:1752–8.

Owens BD, Dawson L, Burks R, Cameron KL. Incidence of shoulder dislocation in the united states military: Demographic considerations from a high-risk population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:791–6.

Randelli P, Ragone V, Carminati S, Cabitza P. Risk factors for recurrence after bankart repair a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:2129–38.

Thomazeau H, Courage O, Barth J, et al. Can we improve the indication for bankart arthroscopic repair? A preliminary clinical study using the ISIS score. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(8 Suppl):S77–83.

Sugaya H, Moriishi J, Dohi M, Kon Y, Tsuchiya A. Glenoid rim morphology in recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:878–84.

Saito H, Itoi E, Sugaya H, Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Tuoheti Y. Location of the glenoid defect in shoulders with recurrent anterior dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:889–93.

Ji J, Kwak D, Yang P, Kwon MJ, Han S, Jeong J. Comparisons of glenoid bony defects between normal cadaveric specimens and patients with recurrent shoulder dislocation: An anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:822–7.

Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic bankart repairs: Significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging hill-sachs lesion. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:677–94.

Burkhart SS, Debeer JF, Tehrany AM, Parten PM. Quantifying glenoid bone loss arthroscopically in shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:488–91.

Itoi E, Lee SB, Berglund LJ, Berge LL, An KN. The effect of a glenoid defect on anteroinferior stability of the shoulder after bankart repair: A cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:35–46.

Gerber C, Nyffeler RW. Classification of glenohumeral joint instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;400:65–76.

Itoi E, Lee SB, Amrami KK, Wenger DE, An KN. Quantitative assessment of classic anteroinferior bony bankart lesions by radiography and computed tomography. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:112–8.

Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H, et al. Effect of an anterior glenoid defect on anterior shoulder stability: A cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:949–54.

Barchilon VS, Kotz E, Barchilon Ben-Av M, Glazer E, Nyska M. A simple method for quantitative evaluation of the missing area of the anterior glenoid in anterior instability of the glenohumeral joint. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:731–6.

Huijsmans PE, Haen PS, Kidd M, Dhert WJ, van der Hulst VPM, Willems WJ. Quantification of a glenoid defect with three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:803–9.

Yiannakopoulos CK, Mataragas E, Antonogiannakis E. A comparison of the spectrum of intra-articular lesions in acute and chronic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:985–90.

Saito H, Itoi E, Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Tuoheti Y, Seki N. Location of the hill-sachs lesion in shoulders with recurrent anterior dislocation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(10):1327–34.

Kaar SG, Fening SD, Jones MH, Colbrunn RW, Miniaci A. Effect of humeral head defect size on glenohumeral stability: A cadaveric study of simulated hill-sachs defects. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:594–9.

Sekiya JK, Wickwire AC, Stehle JH, Debski RE. Hill-sachs defects and repair using osteoarticular allograft transplantation: Biomechanical analysis using a joint compression model. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2459–66.

Sekiya JK, Jolly J, Debski RE. The effect of a hill-sachs defect on glenohumeral translations, in situ capsular forces, and bony contact forces. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:388–94.

Cetik O, Uslu M, Ozsar BK. The relationship between hill-sachs lesion and recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73:175–8.

Boileau P, Villalba M, Hery JY, Balg F, Ahrens P, Neyton L. Risk factors for recurrence of shoulder instability after arthroscopic bankart repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1755–63.

Widjaja AB, Tran A, Bailey M, Proper S. Correlation between bankart and hill-sachs lesions in anterior shoulder dislocation. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:436–8.

Walia P, Miniaci A, Jones MH, Fening SD. Theoretical model of the effect of combined glenohumeral bone defects on anterior shoulder instability: A finite element approach. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:601–7.

Moroder P, Hirzinger C, Lederer S, et al. Restoration of anterior glenoid bone defects in posttraumatic recurrent anterior shoulder instability using the J-bone graft shows anatomic graft remodeling. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1544–50.

Magarelli N, Milano G, Sergio P, Santagada DA, Fabbriciani C, Bonomo L. Intra-observer and interobserver reliability of the ‘pico’ computed tomography method for quantification of glenoid bone defect in anterior shoulder instability. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:1071–5.

Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Tong CW, Ming CK. Anterior shoulder dislocation: Quantification of glenoid bone loss with CT. AJRAm J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1423–30.

Huysmans PE, Haen PS, Kidd M, Dhert WJ, Willems JW. The shape of the inferior part of the glenoid: A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:759–63.

Nofsinger C, Browning B, Burkhart SS, Pedowitz RA. Objective preoperative measurement of anterior glenoid bone loss: A pilot study of a computer-based method using unilateral 3-dimensional computed tomography. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:322–9.

Cho SH, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Preoperative analysis of the hill-sachs lesion in anterior shoulder instability: How to predict engagement of the lesion. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2389–95.

Hardy P, Lopes R, Bauer T, Conso C, Gaudin P, Sanghavi S. New quantitative measurement of the hill-sachs lesion: A prognostic factor for clinical results of arthroscopic glenohumeral stabilization. Eur J Orthop Surg Trauma. 2012;22:541–7.

Ito H, Takayama A, Shirai Y. Radiographic evaluation of the hill-sachs lesion in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder instability. Journal of Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. 2000;9:495–7.

Kralinger FS, Golser K, Wischatta R, Wambacher M, Sperner G. Predicting recurrence after primary anterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:116–20.

Arksey H, O’malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. 5908-5-69.

Bishop JY, Jones GL, Rerko MA, Donaldson C, MOON Shoulder G. 3-D CT is the most reliable imaging modality when quantifying glenoid bone loss. Clin Orthop. 2013;471:1251–6.

Murachovsky J, Bueno RS, Nascimento LG, et al. Calculating anterior glenoid bone loss using the bernageau profile view. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1231–7.

Rerko MA, Pan X, Donaldson C, Jones GL, Bishop JY. Comparison of various imaging techniques to quantify glenoid bone loss in shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:528–34.

Jankauskas L, Rüdiger HA, Pfirrmann CWA, Jost B, Gerber C. Loss of the sclerotic line of the glenoid on anteroposterior radiographs of the shoulder: A diagnostic sign for an osseous defect of the anterior glenoid rim. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:151–6.

Sommaire C, Penz C, Clavert P, Klouche S, Hardy P, Kempf JF. Recurrence after arthroscopic bankart repair: Is quantitative radiological analysis of bone loss of any predictive value? Orthop Trauma Surg Res. 2012;98:514–9.

Charousset C, Beauthier V, Bellaïche L, Guillin R, Brassart N, Thomazeau H. Can we improve radiological analysis of osseous lesions in chronic anterior shoulder instability? Orthop Trauma Surg Res. 2010;96:S88–93.

Gyftopoulos S, Hasan S, Bencardino J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in the measurement of glenoid bone loss. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:873–8.

Dumont GD, Russell RD, Browne MG, Robertson WJ. Area-based determination of bone loss using the glenoid arc angle. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1030–5.

Moroder P, Resch H, Schnaitmann S, Hoffelner T, Tauber M. The importance of CT for the pre-operative surgical planning in recurrent anterior shoulder instability. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133:219–26.

Tian CY, Shang Y, Zheng ZZ. Glenoid bone lesions: Comparison between 3D VIBE images in MR arthrography and nonarthrographic MSCT. J Magnet Res Imag. 2012;36:231–6.

Lee RKL, Griffith JF, Tong MMP, Sharma N, Yung P. Glenoid bone loss: Assessment with MR imaging. Radiology. 2013;267:496–502.

Owens BD, Burns TC, Campbell SE, Svoboda SJ, Cameron KL. Simple method of glenoid bone loss calculation using ipsilateral magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:622–4.

Saccomanno MF, Deriu L, De Ieso C, Logroscino G, Milano G, Fabbriciani C. Analysis of agreement between computed tomography measurements of glenoid bone defect with and without comparison with the contralateral shoulder. J Orthop TraumaConf: 96th National Congress Italian Soc Orthop Trauma Rimini ItalyConference Publication: (varpagings). 2011;12:S32.

Milano G, Grasso A, Russo A, et al. Analysis of risk factors for glenoid bone defect in anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1870–6.

Tauber M, Moursy M, Eppel M, Koller H, Resch H. Arthroscopic screw fixation of large anterior glenoid fractures. Knee Surg, Sport Trauma Arthroscopy. 2008;16:326–32.

Magarelli N, Milano G, Baudi P, et al. Comparison between 2D and 3D computed tomography evaluation of glenoid bone defect in unilateral anterior gleno-humeral instability. Radiol Med. 2012;117:102–11.

Griffith JF, Yung PSH, Antonio GE, Tsang PH, Ahuja AT, Kai MC. CT compared with arthroscopy in quantifying glenoid bone loss. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(6):1490–3.

Diederichs G, Seim H, Meyer H, et al. CT-based patient-specific modeling of glenoid rim defects: A feasibility study. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1406–11.

Park J, Lee S, Lhee S, Lee S. Follow-up computed tomography arthrographic evaluation of bony bankart lesions after arthroscopic repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:465–73.

Lee RKL, Griffith JF, Tong MMP, Sharma N, Yung P. Glenoid bone loss: Assessment with MR imaging. Radiology. 2013;267:496–502.

Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Yung PS, et al. Prevalence, pattern, and spectrum of glenoid bone loss in anterior shoulder dislocation: CT analysis of 218 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1247–54.

Bois AJ, Fening SD, Polster J, Jones MH, Miniaci A. Quantifying glenoid bone loss in anterior shoulder instability: Reliability and accuracy of 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional computed tomography measurement techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2569–77.

Huijsmans PE, De Witte PB, De Villiers RVP, et al. Recurrent anterior shoulder instability: Accuracy of estimations of glenoid bone loss with computed tomography is insufficient for therapeutic decision-making. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:1329–34.

Hantes ME, Venouziou A, Bargiotas KA, Metafratzi Z, Karantanas A, Malizos KN. Repair of an anteroinferior glenoid defect by the latarjet procedure: Quantitative assessment of the repair by computed tomography. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:1021–6.

De Filippo M, Castagna A, Steinbach LS, et al. Reproducible noninvasive method for evaluation of glenoid bone loss by multiplanar reconstruction curved computed tomographic imaging using a cadaveric model. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:471–7.

D’Elia G, Di Giacomo A, D’Alessandro P, Cirillo LC. Traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability: Quantification of glenoid bone loss by spiral CT. Radiol Med. 2008;113:496–503.

Chuang TY, Adams CR, Burkhart SS. Use of preoperative three-dimensional computed tomography to quantify glenoid bone loss in shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:376–82.

Van Den Bogaert M, Van Dijk M, Heylen S, Foubert K, Van Glabbeek F. Validation of a CT-based determination of the glenohumeral index. Acta Orthop Belg. 2011;77:167–70.

Kirkley A, Litchfield R, Thain L, Spouge A. Agreement between magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic evaluation of the shoulder joint in primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:148–51.

Salomonsson B, von Heine A, Dahlborn M, et al. Bony bankart is a positive predictive factor after primary shoulder dislocation. Knee Surg Sport Trauma Arthroscopy. 2010;18:1425–31.

Kodali P, Jones MH, Polster J, Miniaci A, Fening SD. Accuracy of measurement of hill-sachs lesions with computed tomography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:1328–34.

Kawasaki S, Nakaguchi T, Ochiai N, Tsumura N, Miyake Y. Quantitative evaluation of humeral head defects by comparing left and right feature - art. no. 69153F. Med Imaging 2008: Computer-Aided Diagnosis, Pts 1 and 2. 2008;6915:F9153.

Bigliani LU, Newton PM, Steinmann SP, Connor PM, Mcllveen SJ. Glenoid rim lesions associated with recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:41–5.

Baudi P, Righi P, Bolognesi D, Rivetta S, Rossi Urtoler E, Guicciardi N, et al. How to identify and calculate glenoid bone deficit. Chir Organi Mov. 2005;90(2):145-52.

Acknowledgements

LB receives salary support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as a New Investigator (Patient Oriented Research) and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions as a Population Health Investigator.

DMS, MB and LB are members of the Shoulder and Upper Extremity Research Group of Edmonton (SURGE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DJS, TB, MB, DMS, LB contributed to study concept and design; DS and TB performed data acquisition; DJS, TB, MB, DMS, LB contributed to data analysis, interpretation and drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix 1_BMC.docx; This is a Microsoft Word file that contains the Search Strategy for the scoping review.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Saliken, D.J., Bornes, T.D., Bouliane, M.J. et al. Imaging methods for quantifying glenoid and Hill-Sachs bone loss in traumatic instability of the shoulder: a scoping review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16, 164 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0607-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0607-1