Abstract

Background

Rehabilitation, with an emphasis on physiotherapy and exercise, is widely promoted after total knee replacement. However, provision of services varies in content and duration. The aim of this study is to update the review of Minns Lowe and colleagues 2007 using systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of post-discharge physiotherapy exercise in patients with primary total knee replacement.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo, CINAHL and Cochrane CENTRAL to October 4th 2013 for randomised evaluations of physiotherapy exercise in adults with recent primary knee replacement.

Outcomes were: patient-reported pain and function, knee range of motion, and functional performance. Authors were contacted for missing data and outcomes. Risk of bias and heterogeneity were assessed. Data was combined using random effects meta-analysis and reported as standardised mean differences (SMD) or mean differences (MD).

Results

Searches identified 18 randomised trials including 1,739 patients with total knee replacement. Interventions compared: physiotherapy exercise and no provision; home and outpatient provision; pool and gym-based provision; walking skills and more general physiotherapy; and general physiotherapy exercise with and without additional balance exercises or ergometer cycling.

Compared with controls receiving minimal physiotherapy, patients receiving physiotherapy exercise had improved physical function at 3–4 months, SMD −0.37 (95% CI −0.62, −0.12), and pain, SMD −0.45 (95% CI −0.85, −0.06). Benefit up to 6 months was apparent when considering only higher quality studies.

There were no differences for outpatient physiotherapy exercise compared with home-based provision in physical function or pain outcomes. There was a short-term benefit favouring home-based physiotherapy exercise for range of motion flexion.

There were no differences in outcomes when the comparator was hydrotherapy, or when additional balancing or cycling components were included. In one study, a walking skills intervention was associated with a long-term improvement in walking performance. However, for all these evaluations studies were under-powered individually and in combination.

Conclusion

After recent primary total knee replacement, interventions including physiotherapy and exercise show short-term improvements in physical function. However this conclusion is based on meta-analysis of a few small studies and no long-term benefits of physiotherapy exercise interventions were identified. Future research should target improvements to long-term function, pain and performance outcomes in appropriately powered trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the year to 31st March 2013, over 75,000 primary total knee replacements were performed by the NHS in England and Wales with about 97% of procedures subsequent to osteoarthritis [1]. In the USA in 2010, the estimated number of hospital discharges after total knee replacement procedures was 719,000 [2]. Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of pain and disability in older people [3,4] and if pharmacological and conservative treatments do not relieve symptoms joint replacement is recommended [5].

Rehabilitation, with a particular emphasis on physiotherapy and exercise, is widely promoted after total knee replacement [6]. During the hospital stay, physiotherapy targets mobilisation and achievement of functional goals relating to hospital discharge. Further post-discharge physiotherapy and exercise-based interventions promote re-training and functional improvement. However, provision of these services varies in content and duration [7,8].

Minns Lowe and colleagues reviewed evidence from 6 randomised trials with 614 patients on the effectiveness of post-discharge physiotherapy after total knee replacement [9]. Since their literature search in 2007, additional trials have been published. Our aim was to update the review and further explore the possible benefit of specific physiotherapy modalities.

Methods

We used systematic review methods as described in the Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews [10], and reported the review in accordance with the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials [11].

Types of studies

To eliminate selection bias, we included studies that were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with randomisation either at the individual or cluster level. We also included studies with a quasi-randomised design (for example alternate allocation). Studies reported only as abstracts, or that we were unable to acquire as full text copies using interlibrary loans or email contact with authors, were excluded from the analyses. Studies where patients with total knee replacement were identified retrospectively were also excluded. No language restrictions were applied.

Participants

Adults with recent primary total knee replacement.

Types of interventions

We included any physiotherapy or exercise-based intervention. Interventions commenced at a pre-specified time after discharge from the hospital; typically at 2–12 weeks, and were either outpatient, community or home-based. We included studies comparing physiotherapy exercise interventions with: usual or standard care; different types of intervention including home-based; and enhanced physiotherapy formats with additional components. Interventions including electrical stimulation, acupuncture or electrical modalities such as continuous passive motion were excluded as these were considered as adjunct to physiotherapy or exercise-based intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO on the OvidSP platform, CINAHL and Cochrane Library databases were searched from inception to 4th October 2013. Search terms related to: hip and knee replacement; randomised controlled trial; and exercise, rehabilitation and physiotherapy. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses were checked [9,12]. Citations of key articles in ISI Web of Science were checked and reference lists searched. Articles identified were managed in an Endnote X5 database.

Inclusion/exclusion

Full articles relating to potentially relevant abstracts identified during initial screening were obtained and assessed independently for eligibility, based on the defined inclusion criteria, by two reviewers (NA, KTE). If there was any doubt a third reviewer was consulted (ADB).

Data extraction

Data extraction was undertaken in duplicate (NA, KTE, ADB). Reasons for exclusion at this stage were summarised. Results were recorded on a piloted data extraction form and Excel spreadsheet. Data was extracted on: country and dates of study; participants (indication, age, sex); inclusion and exclusion criteria; content of intervention and comparison (control) group; setting, timing, duration and intensity of intervention; follow up duration; losses to follow up and reasons; and outcomes.

For outcomes reported as continuous variables, means and standard deviations were extracted. If outcomes were reported as means and confidence intervals, or medians and inter-quartile ranges, appropriate conversions were applied [10].

The primary author of the study was contacted for missing data if necessary. We also asked if any outcomes not reported in their publications had been collected. If authors had provided information to other reviewers this data was included in our analyses and acknowledged appropriately.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Potential sources of bias were assessed according to the Cochrane risk of bias table [10]. Bias was assessed on the grounds of: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources. In the context of post-surgical physiotherapy exercise, participants and therapists were generally unable to be blinded to the intervention. Quality was judged as: Good; Reasonable (e.g. non-blind follow up with self-complete questionnaires); or Possible bias (unequal or major loss to follow up, or important baseline differences).

Data synthesis

If sufficient studies reported common outcomes, data was combined as standardised mean differences using random effects meta-analysis [10,13]. Where outcomes used the same measurement scale we combined data as the mean difference.

Heterogeneity between included studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. Possible heterogeneity arising from inclusion of studies of different methodological quality was investigated based on the risk of bias assessment. Funnel plots were used to explore publication bias.

Results

Included studies

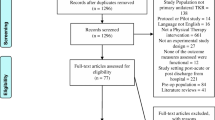

Review progress is summarised as a flow diagram in Figure 1. Eighteen eligible randomised controlled trials were identified. Reasons for exclusion are summarised in Additional file 1 and excluded studies are listed in Additional file 2.

Characteristics of the 18 included studies are presented in Table 1. Studies ranged in size from 43–160 patients (median 94) and included a total of 1,739 patients. Where reported, the main diagnosis was osteoarthritis, and the mean age in studies ranged from 66 to 73.5 years. The duration of follow up ranged from 3 weeks to 24 months, though we describe data in our meta-analysis from 3 months onwards.

Intervention focus

The focus of the intervention was: movement and exercise [14-16], exercises aimed at managing kinesophobia [17], functional [18,19] or strengthening exercise [20], compared with minimal physiotherapy exercise in seven studies; home compared with outpatient provision in six studies [21-26]; physiotherapy with additional balance [27,28] or cycling components [29] compared with standard physiotherapy in three studies; walking skills compared with more general physiotherapy in one study [30]; and pool-based compared with gym-based provision in one study [31]. Interventions commenced within 6 months of surgery and in the majority of studies within 2 months.

Patient adherence

Where information was available, patient adherence to the intervention was good with 60% or more of patients completing programmes.

Outcome measures

Outcomes reported in studies were classified as: patient reported physical function or pain; physiological tests; physical performance tests; and generic health related quality of life measures. The most frequently used physiological outcome was knee range of motion (ROM) expressed as extension and/or flexion in 10 studies [14-16,18,20,23,25,28,30,31]. Less frequently reported outcomes were isometric muscle strength, leg power, and knee oedema. Performance measures reported were walking (walking speed, metres walked in specified time, and time to walk a specified distance), stair ascent and descent tests, and chair rise tests. The 6-minute walk test was the most frequently reported test of walking performance reported in 4 studies.

Study quality

We completed a risk of bias assessment for each study and summarised these in Table 2. The main potential source of bias was from large and uneven losses to follow up in six studies. Two further studies were judged to be of reasonable quality with overall losses to follow up between 10 and 20%. There was no suggestion of risk of bias in nine studies. There was no clear evidence of publication bias from inspection of funnel plots. However numbers of studies were small for several outcomes and in sub-group analyses.

Comparison of different physiotherapy interventions

Results for comparisons of physiotherapy exercise and no intervention and home-based and outpatient delivery are summarised in Table 3. Meta-analyses used random effects models, an a priori decision based on the known variation in physiotherapy exercise content. Pooled effect sizes are standardised mean differences except for range of motion where mean differences are reported. For the other interventions we provide a brief narrative summary of outcomes.

Physiotherapy exercise compared with minimal intervention

In seven studies, patients randomised to physiotherapy exercise intervention were compared with a control group receiving no intervention or minimal intervention [14-20]. For control group patients, minimal treatment was either only inpatient rehabilitation common to both groups [20], or instructions on home exercise given before discharge [15-19] or at a two-month post-operative outpatient appointment [14].

Patient reported physical function

Results for all intervention comparisons and outcomes are summarised in Table 3.

Data was available at one or more time points for 5 studies that compared a physiotherapy intervention with a control group that received minimal physiotherapy [14,15,17,19,20]. Studies reported Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function, Oxford Knee Score, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) activities of daily living scale or Iowa Level of Assistance Scale (ILAS) total score.

As shown in the meta-analysis in Table 3 and Figure 2, at 3–4 months, physiotherapy exercise was associated with an improvement in physical function in 3 studies with 254 patients [15,19,20], average SMD −0.37 (95% CI −0.62, −0.12; p = 0.004). At 6 months there was a non-significant trend for benefit in 3 studies [14,17,19], SMD −0.43 (95%CI −0.95, 0.08; p = 0.10), and little difference between groups in 4 studies [14,15,17,19] at 12 months. Heterogeneity was high in studies reporting outcomes at 6 and 12 months and this was not explained by inclusion of studies with high risk of bias [14,20]. After exclusion of these studies, benefit was apparent at both 3 and particularly at 6 months, SMD −0.64 (95% CI −1.15, −0.13; p = 0.01), but included only 2 studies at each follow up.

Patient reported pain

Four studies reported a pain outcome at one or more follow up times [14,17-19]. Studies reported WOMAC pain, KOOS pain or OKS pain. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, in two studies with 103 patients [18,19], a pain outcome was reported at 3–4 months with average SMD −0.45 (95% CI −0.85, −0.06; p = 0.02) favouring physiotherapy exercise. There was a trend for benefit at 6 months in 4 studies with 287 patients [14,17,18,32], average SMD −0.29 (95% CI −0.68, 0.10; p = 0.15). At 12 month follow up there was little to suggest benefit for patients receiving physiotherapy exercise compared with untreated controls in 4 studies with 281 patients [14,17,18,32]. Heterogeneity was high at 6 and 12 month follow up. Only one study had low risk of bias at each of 3–4 and 12 months [17] precluding meta-analysis. At 6 months, 2 higher quality studies [17,19] showed benefit, average SMD −0.58 (95% CI −0.88, −0.29; p = 0.0001).

Range of motion

ROM extension data suitable for meta-analysis was available from 3 studies with 252 patients [14,15,20], and ROM flexion from 5 studies with 396 patients [14-16,18,20]. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 4, there was little to suggest long-term benefit for outpatient physiotherapy improved long-term ROM extension. Benefit was only evident in 2 studies with follow up at 3 months after total knee replacement. For ROM flexion there was evidence of improved flexion in patients receiving physiotherapy exercise, particularly after 6 and 12 months. Benefit was seen in studies with low risk of bias but this was based on a small number of studies.

Physical performance

Measures of walking performance (metres walked in a set time, time to walk a specified distance and walking speed) were combined with attention paid to direction of effect. An improvement in walking performance in three3 studies with 169 patients [14,18,19] was not significant, average SMD −0.17 (95% CI −0.48, 0.13; p = 0.27). There was no heterogeneity across studies.

Home-based compared with outpatient delivery of physiotherapy exercise

Home-based provision was compared with outpatient physiotherapy in six studies [21-26].

Patient reported physical function

Data was available at one or more time points for five studies comparing the outcomes of home-based physiotherapy exercise with outpatient or standard provision [21,22,24-26].

Physical function was measured using WOMAC, KOOS and OKS in 5 studies with up to 436 patients followed up [21,22,24-26]. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, there was no suggestion of a difference in functional outcome between home and outpatient provision at 3–4 months, 6 months or 12 months. For example at 3–4 months, the average SMD was −0.03 (95% CI −0.25, 0.19; p = 0.80). No heterogeneity was apparent and consideration of higher quality studies did not suggest any difference in outcomes after home or outpatient physiotherapy exercise. However numbers of studies to base this on were small.

Patient reported pain

Studies reported WOMAC pain, KOOS pain or VAS pain. Data was available at 3–4 months for three studies with 248 patients [21,22,24]. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 6, there was no difference in pain outcome between patients randomised to home-based or outpatient physiotherapy exercise, average SMD −0.00 (95% CI −0.25, 0.25;p = 0.98). One study followed up 85 and 92 patients at 6 and 12 months [21] and showed no benefit for reduced pain at either follow up.

Range of motion

ROM extension was reported in 3 studies with 261 patients [21,23,24] and ROM flexion in five studies with 448 patients [21,23-26]. Outcomes are summarised in Table 3 and Figure 7. There was no suggestion of a difference in ROM extension between randomised groups at any time point. For ROM flexion there was an improved ROM flexion at 3–4 months in patients who received home-based physiotherapy exercise compared with outpatient provision [21,23-25]. This was maintained in studies with low risk of bias [21,23,24]. There was no evidence for longer term benefit in 2 studies [21,26].

Physical performance

In 3 studies with 267 patients randomised [21,25,26] there was no suggestion that walking performance differed between groups.

Pool-based physiotherapy

One study compared pool-based physiotherapy with gym-based provision [31]. There were no differences between treatments in WOMAC physical function, WOMAC pain or ROM extension and flexion at the end of the interventions and at 26 week follow up.

Walking skills

In one study a walking skills programme was provided from 6 weeks after surgery for 6–8 weeks. A comparison group received “usual physiotherapy care”. All patients previously received extensive physiotherapy after surgery at a rehabilitation centre and subsequently in an outpatient setting [30]. There were no statistically significant differences in KOOS outcomes or ROM between groups at 9 months. However a difference in the 6 minute walk test favouring the walking skills group noted immediately after the intervention was sustained at 9 months.

Additional physiotherapy components

One study with 159 patients evaluated addition of ergometer cycling to a general physiotherapy intervention [29]. There were no differences in pain outcome between randomised groups at any of the follow up intervals from 3–4 months to 24 months.

Two studies evaluated addition of a balancing component to a general physiotherapy intervention with a total of 93 patients randomised [27,28]. Studies reported different follow up times but individually there was no evidence for improvement in LEFS or WOMAC physical function. Similarly, NRS pain and WOMAC pain were similar at all follow up periods. One study which included additional balance training reported ROM extension and flexion at short term follow up [28]. There were no differences in either measure between intervention and control groups.

Discussion

Randomised controlled trials of physiotherapy and exercise interventions after total knee replacement provide some evidence for-short term effectiveness. In the key analysis comparing patients who received a programme of physiotherapy exercise with those receiving no intervention there were short-term benefits for physical function, SMD −0.37 (95% CI −0.62, −0.12; p = 0.004), and pain, SMD −0.45 (95% CI −0.85, −0.06; p = 0.02). However, these small to medium sized effects [33], were based on only 3 studies with 254 patients, and 2 studies with 103 patients randomised respectively. No benefit was apparent regarding longer-term improvements to function and pain in the randomised controlled trials of physiotherapy exercise that we identified. For physical function this observation was based on 4 studies with high heterogeneity which was not explained by consideration of the 2 studies with low risk of bias.

With a more robust evidence base this could be interpreted as a speeding up of recovery attributable to physiotherapy exercise but with a similar long-term level of recovery irrespective of post-discharge care. More realistically it suggests the need for appropriately powered studies.

There is no up-to-date national guidance to support the facilitation of early recovery using exercise-based rehabilitation. Physiotherapy should also address patient expectations [34,35], since the key expectations of patients undergoing knee replacement relate to long-term functional and pain outcomes [36-39]. Strategies to improve communication and provide patients with a better understanding of realistic expectations after knee replacement need to be considered prior to surgery [35].

The problems of poor medium to long-term patient outcomes after total knee replacement are recognised. Judge and colleagues assessed functional improvement according to a number of success criteria and concluded that 14–36% of patients did not improve or were worse 12 months after surgery [40]. In a study of patients with moderate to severe hip or knee arthritis, Hawker and colleagues reported that only about 50% of patients had a clinically important improvement in WOMAC score at a median of 16 months after surgery [41]. Regarding post-surgical pain [42], unfavourable outcomes were reported by 10 to 34% of knee replacement patients in 11 representative populations identified by Beswick and colleagues. There is clearly a need for rehabilitation strategies that can enhance recovery for the majority of patients and target patients whose post-surgical experience is unfavourable. Westby and Backman highlighted the importance of utilising strategies to empower patients in the rehabilitation process [35]. Provision of tailored rehabilitation programmes may assist in maximising individual outcome after surgery and are worthy of further research.

Knee range of motion is commonly measured after knee replacement and is a component of clinician-based outcome measures such as the Knee Society Clinical Rating System [43]. Across the trials reporting range of motion, we observed benefit for physiotherapy exercise in studies with low risk of bias compared with controls for flexion only. However, although useful as a trial outcome [16], ROM is considered a poor marker of implant success [44,45], and may not influence patient satisfaction with their replacement [46]. As with all the results of our meta-analyses, conclusions are limited by the small number of small studies that we identified.

The need for measures of both gait and a patient reported functional outcome is recognised [47,48]. A measure of walking performance was included in over half of the studies we identified but we were unable to identify any benefit from physiotherapy exercise. In four higher quality studies there was a trend for benefit but this was not statistically significant.

Studies of physiotherapy exercise after hospital discharge are pragmatic in nature with patients who have consented to be randomised free to participate to whatever extent they choose or to seek physiotherapy exercise additional to that in their allocated group. When reported, uptake and adherence by patients randomised to groups with a specific physiotherapy exercise intervention was good. A limitation of the review is the possibility that patients in the minimally treated control group received some physiotherapy. We did not anticipate that being allocated to a control group would preclude the possibility of referral for physiotherapy on the basis of individual clinical need. For example, Moffet and colleagues reported that about a quarter of control group patients received some home physiotherapy service [19]. However, in the subgroup of studies comparing physiotherapy exercise provision with minimal provision there was little to suggest overlap with the subgroups comparing alternative methods of provision.

There were insufficient studies with adequate patient numbers to provide conclusive evidence on different methods of provision. Physiotherapy exercise provided at home is an appealing approach with the possibility of wider acceptability and uptake. However, equivalence or non-inferiority trials need large numbers of patients and have yet to be undertaken. Our meta-analysis included only 310 patients for the short-term physical function outcome and less for the key longer-term outcomes. Similar issues of study size affect interpretation of physiotherapy exercise provided in a hydrotherapy pool, enhanced with additional cycling and balancing components, or focusing on walking skills. This highlights the difficulty of developing a complex physiotherapy exercise intervention.

A search for ongoing trials in ClinicalTrials.gov identified some randomised trials of physiotherapy exercise in total knee replacement. These are evaluating the effect of additional strength training [49,50], independent exercise prescription compared with supervised exercise [51], and progressive resistance rehabilitation compared with traditional rehabilitation [52]. One ongoing study will evaluate intensive physiotherapy for patients performing poorly at 6 weeks following total knee replacement [53]. Targeting physiotherapy at those with greatest functional need may be a valuable approach but many other patients have sub-optimal outcomes [54], and may also benefit from appropriate intervention.

An important problem that home-based physiotherapy exercise may address is that uptake of rehabilitation is frequently low and that patients who do not attend are more likely to be those with poorer functional health. Optimising uptake and adherence to interventions is an important issue in rehabilitation [55,56]. In their systematic review of interventions for enhancing adherence with physiotherapy, McLean and colleagues found only short-term evidence of effectiveness of exercise adherence strategies and little evidence that home based-interventions are associated with good adherence [55]. They concluded that a strategy to improve adherence to physiotherapy treatment should probably be multi-dimensional.

Despite the inclusion of 18 randomised controlled trials compared with 6 trials in the review of Minns Lowe and colleagues, our conclusion is similar with a possible short-term benefit for physiotherapy exercise after knee replacement. There was only limited evidence from a single small study focusing on walking skills to suggest that any benefit was maintained at longer-term follow up. We concur with Minns Lowe and colleagues and Muller and colleagues [12] that further research is needed.

Some physiotherapy exercise will generally be provided to patients with total knee replacement even if this only comprises advice following on from inpatient rehabilitation. Healthcare professionals and policy makers need to know what content and duration of physiotherapy exercise is necessary to improve short and long-term outcomes and which patients are likely to benefit. Appropriate care can then be provided to each individual patient. Future studies should include credible evaluation of methods with well-designed and appropriately powered randomised trials with a focus on completeness of follow up.

Conclusion

After recent primary total knee replacement, physiotherapy exercise interventions show short-term improvements in physical function. However this conclusion is based on meta-analysis of a few small studies and no long-term benefits of physiotherapy or exercise intervention were identified.

Abbreviations

- SMD:

-

Standardised mean differences

- MD:

-

Mean differences

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities arthritis index

- KOOS:

-

Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score

- ILAS:

-

Iowa level of assistance scale

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- OKS:

-

Oxford Knee Score

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- NRS:

-

Numerical rating scale

References

National Joint Registry. 10th Annual Report 2013. Hemel Hempstead: NJR Centre.

National Hospital Discharge Survey. Public data file documentation. Atlanta, US: U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics; 2010.

Spiers NA, Matthews RJ, Jagger C, Matthews FE, Boult C, Robinson TG, et al. Diseases and impairments as risk factors for onset of disability in the older population in England and Wales: Findings from the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(2):248–54.

Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults. Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55(2):248–55.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoarthritis: Care and management in adults. London: NICE; 2014.

BOA, BASK. Knee replacement: a guide to good practice. London: British Orthopaedic Association; 1999.

Artz N, Dixon S, Wylde V, Beswick A, Blom A, Gooberman-Hill R. Physiotherapy provision following discharge after total hip and total knee replacement: a survey of current practice at high-volume NHS hospitals in England and Wales. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11(1):31–8.

Oatis CA, Li W, DiRusso JM, Hoover MJ, Johnston KK, Butz MK, et al. Variations in delivery and exercise content of physical therapy rehabilitation following total knee replacement surgery: a cross-sectional observation study. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;S5:002. doi:10.4172/2329-9096.S5-002.

Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Dewey M, Sackley CM. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise after knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Bmj. 2007;335(7624):812.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. ᅟ: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

Muller E, Mittag O, Gulich M, Uhlmann A, Jackel WH. Systematic literature analysis on therapies applied in rehabilitation of hip and knee arthroplasty: methods, results and challenges. Die Rehabilitation. 2009;48(2):62–72.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Kauppila AM, Kyllonen E, Ohtonen P, Hamalainen M, Mikkonen P, Laine V, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation after primary total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled study of its effects on functional capacity and quality of life. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(5):398–411.

Mockford BJ, Thompson NW, Humphreys P, Beverland DE. Does a standard outpatient physiotherapy regime improve the range of knee motion after primary total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(8):1110–4.

Rajan RA, Pack Y, Jackson H, Gillies C, Asirvatham R. No need for outpatient physiotherapy following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial of 120 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(1):71–3.

Monticone M, Ferrante S, Rocca B, Salvaderi S, Fiorentini R, Restelli M, et al. Home-based functional exercises aimed at managing kinesiophobia contribute to improving disability and quality of life of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2013;94(2):231–9.

Frost H, Lamb SE, Robertson S. A randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve mobility and function after elective knee arthroplasty. Feasibility, results and methodological difficulties. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(2):200–9.

Moffet H, Collet J-P, Shapiro SH, Paradis G, Marquis F, Roy L. Effectiveness of intensive rehabilitation on functional ability and quality of life after first total knee arthroplasty: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2004;85(4):546–56.

Evgeniadis G, Beneka A, Malliou P, Mavromoustakos S, Godolias G. Effects of pre- or postoperative therapeutic exercise on the quality of life, before and after total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Back Musculoskelet. 2008;21(3):161–9.

Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Holder R, Sackley CM. Comparison of postdischarge physiotherapy versus usual care following primary total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: an exploratory pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(7):629–41.

Mitchell C, Walker J, Walters S, Morgan AB, Binns T, Mathers N. Costs and effectiveness of pre- and post-operative home physiotherapy for total knee replacement: randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(3):283–92.

Piqueras M, Marco E, Coll M, Escalada F, Ballester A, Cinca C, et al. Effectiveness of an interactive virtual telerehabilitation system in patients after total knee arthoplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(4):392–6.

Tousignant M, Moffet H, Boissy P, Corriveau H, Cabana F, Marquis F. A randomized controlled trial of home telerehabilitation for post-knee arthroplasty. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(4):195–8.

Madsen M, Larsen K, Kirkegard Madsen I, Soe H, Hansen TB. Late group-based rehabilitation has no advantages compared with supervised home-exercises after total knee arthroplasty. Dan Med J. 2013;60(4):A4607.

Kramer JF, Speechley M, Bourne R, Rorabeck C, Vaz M. Comparison of clinic- and home-based rehabilitation programs after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;410:225–34.

Piva SR, Gil AB, Almeida GJM, DiGioia 3rd AM, Levison TJ, Fitzgerald GK. A balance exercise program appears to improve function for patients with total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90(6):880–94.

Fung V, Ho A, Shaffer J, Chung E, Gomez M. Use of Nintendo Wii FitTM in the rehabilitation of outpatients following total knee replacement: a preliminary randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(3):183–8.

Liebs TR, Herzberg W, Ruther W, Haasters J, Russlies M, Hassenpflug J. Ergometer cycling after hip or knee replacement surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):814–22.

Bruun-Olsen V, Heiberg KE, Wahl AK, Mengshoel AM. The immediate and long-term effects of a walking-skill program compared to usual physiotherapy care in patients who have undergone total knee arthroplasty (TKA): a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(23):2008–15.

Harmer AR, Naylor JM, Crosbie J, Russell T. Land-based versus water-based rehabilitation following total knee replacement: a randomized, single-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(2):184–91.

Moffet H. Acupuncture trial with indistinguishable exposures is moot [1]. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(1):71.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Barron CJ, Klaber Moffett JA, Potter M. Patient expectations of physiotherapy: Definitions, concepts, and theories. Physiotherapy Theory Pract. 2007;23(1):37–46.

Westby MD, Backman CL. Patient and health professional views on rehabilitation practices and outcomes following total hip and knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:119.

Scott CEH, Bugler KE, Clement ND, MacDonald D, Howie CR, Biant LC. Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94 B(7):974–81.

Gonzalez Saenz de Tejada M, Escobar A, Herrera C, Garcia L, Aizpuru F, Sarasqueta C. Patient expectations and health-related quality of life outcomes following total joint replacement. Value Health. 2010;13(4):447–54.

Muniesa JM, Marco E, Tejero M, Boza R, Duarte E, Escalada F, et al. Analysis of the expectations of elderly patients before undergoing total knee replacement. Arch Geriontol Geriatr. 2010;51(3):e83–7.

Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Wickiewicz TL, Jones EC, Robbins L, Warren RF, et al. Patients’ expectations of knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(7):1005–12.

Judge A, Cooper C, Williams S, Dreinhoefer K, Dieppe P. Patient-reported outcomes one year after primary hip replacement in a European Collaborative Cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(4):480–8.

Hawker GA, Badley EM, Borkhoff CM, Croxford R, Davis AM, Dunn S, et al. Which Patients Are Most Likely to Benefit From Total Joint Arthroplasty? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1243–52.

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e00043543.

Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:13–4.

Tew M, Forster IW, Wallace WA. Effect of total knee arthroplasty on maximal flexion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;247:168–74.

Park KK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Seong SC, Kim TK. Correlation of maximum flexion with clinical outcome after total knee replacement in Asian patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89-B(5):604–8.

Miner AL, Lingard EA, Wright EA, Sledge CB, Katz JN, Kinemax Outcomes G. Knee range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: how important is this as an outcome measure? J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(3):286–94.

Parent E, Moffet H. Comparative responsiveness of locomotor tests and questionnaires used to follow early recovery after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2002;83(1):70–80.

Lindemann U, Becker C, Unnewehr I, Muche R, Aminin K, Dejnabadi H, et al. Gait analysis and WOMAC are complementary in assessing functional outcome in total hip replacement. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(5):413–20.

The difference between rehabilitation with or without strength training after total knee replacement. [http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01351831?cond=osteoarthritis&intr=exercise+or+physiotherapy&rank=21]

Effective rehabilitation of patients operated with total knee arthroplasty. [http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01877733]

Independent exercise compared with formal rehabilitation following primary total knee replacement. [http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01826305]

Progressive rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty (PROG). [http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01537328]

Targeted rehabilitation to improve outcome after knee replacement- A physiotherapy study (TRIO-Physio). [http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01849445?cond=osteoarthritis&intr=exercise+or+physiotherapy&rank=1]

Nilsdotter A-K, Petersson IF, Roos EM, Lohmander LS. Predictors of patient relevant outcome after total hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(10):923–30.

McLean SM, Burton M, Bradley L, Littlewood C. Interventions for enhancing adherence with physiotherapy: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(6):514–21.

Beswick A, Rees K, West R, Taylor F, Burke M, Griebsch I, et al. Improving uptake and adherence in cardiac rehabilitation: Literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(5):538–55.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors who provided supplementary information and additional data for our meta-analyses: Alison Harmer, Anna-Maija Kauppila, Brian Mockford, Helen Frost, Michel Tousignant, Rohan Rajan, Sara Piva, Simona Ferrante, Thoralf Leibs, Torben Bæk Hansen, Vera Fung and Yvette Bulthius. Data was also included that had been provided for the review of Minns Lowe and colleagues. The assistance of Dr Michael Dewey, who conducted the statistical analyses for this earlier review, is gratefully acknowledged.

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (RP-PG-0407-10070). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: NA, ADB, CML, CS. Analysis and interpretation of the data: NA, KTE, CML, CS, PJ, ADB. Drafting of the article: NA, KTE, ADB. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: CML, CS, PJ. Final approval of the article: NA, KTE, CML, CS, PJ, ADB. Provision of study materials or patients: NA, KTE, ADB. Statistical expertise: CML, CS, ADB. Obtaining of funding: CS, ADB. Administrative, technical, or logistic support: NA, KTE, ADB. Collection and assembly of data: NA, KTE, ADB.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Reasons for exclusion.

Additional file 2:

Reasons for exclusion references.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Artz, N., Elvers, K.T., Lowe, C.M. et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16, 15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0469-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0469-6