Abstract

Background

Active pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is associated with intra-hospital spread of the disease. Expeditious diagnosis and isolation are critical for infection control. However, factors that lead to delayed isolation of smear-positive pulmonary TB patients, especially among the elderly, have not been reported. The purpose of this study is to investigate factors associated with delay in the isolation of smear-positive TB patients.

Methods

All patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB admitted between January 2008 and December 2016 were included. The setting was a Japanese acute care teaching hospital. Following univariate analysis, significant factors in the model were analyzed using the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

Sixty-nine patients with mean age of 81 years were included. The median day to the isolation of pulmonary TB was 1 day with interquartile range, 1–4 days. On univariate analysis, the time to isolation was significantly delayed in male patients (p = 0.009), in patient who had prior treatment with newer quinolone antibiotics (p = 0.027), in patients who did not have chronic cough (p = 0.023), in patients who did not have appetite loss (p = 0.037), and in patients with non-cavitary lesion (p = 0.005), lesion located other than in the upper zone (p = 0.015), and non-disseminated lesion on the chest radiograph (p = 0.028). On multivariate analysis, the time to isolation was significantly delayed in male patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25 to 0.89; P = 0.02), in patients who did not have chronic chough (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.95; P = 0.033), and in patients with non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.92; P = 0.028).

Conclusions

In acute care hospitals of an aging society, prompt diagnosis and isolation of TB patients are important for the protection of other patients and healthcare providers. Delay in isolation is associated with male gender, absence of chronic cough, and presence of non-cavitary lesions on the chest radiograph.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) control is of worldwide interest, especially among patients with active pulmonary TB who are smear-positive for acid-fast bacilli [1]. TB control requires early diagnosis and immediate initiation of treatment [2]. Delay in diagnosis adversely affects clinical outcome; besides, it increases transmission within the community and leads to higher transmission rates in an epidemic [3, 4].

Although the prevalence of TB had reduced to 16.7 per 100,000 among Japanese population in 2012, this figure remains 3–4 times higher than in Europe and North America [5, 6]. One reason for the relatively high prevalence of TB in Japan is an aging population with previous TB infection [7]. In the World Health Organization 2017 global report, Japanese patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB were older and had a higher mortality than in other countries [8, 9]. Given the high rates of hospital admission among elderly patients in developed countries, any delay in diagnosis and isolation of pulmonary TB can cause spread of infection [10]. Therefore, in aging societies including Japan, it is important to seek reasons for delay in the isolation of pulmonary TB patients.

In previous studies, factors leading to delayed diagnosis of pulmonary TB have been well reported worldwide [2, 11,12,13,14]. These reports focused on ‘patient delay’ and ‘health care system delay’ [14,15,16]. Delayed diagnosis has been associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection, chronic cough, and presence of incidental lung disease [2]. Geographical and socio-psychological barriers include rural residence and poor access to healthcare [2, 11, 12]. Other factors that may delay diagnosis include old age, female gender, alcoholism and substance abuse, initial visitation at a low-level government healthcare facility, private practitioner, or traditional healer [2, 11, 12, 14]. History of immigration, poor education status, low awareness of TB, irrational beliefs, self-treatment, the associated stigma, consultation at a public hospital, and prior treatment with fluoroquinolones may also delay the diagnosis of active pulmonary TB [2, 11,12,13,14].

To the best of our knowledge, factors associated with delay in isolation of pulmonary TB patients have not been reported. In the clinical setting, any delay in isolation is critical to control of infection within hospitals. Therefore, we conducted this study to clarify factors associated with delayed isolation of active pulmonary TB patients.

Methods

Patients and setting

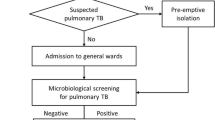

We conducted a retrospective study on patients who were diagnosed with smear-positive pulmonary TB in an urban teaching hospital between January 2008 and December 2016. The hospital provides primary through tertiary care in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, with a population of about nine million people. The hospital has no specific wards for patients with treatment of active pulmonary TB. Those who are suspected to have active pulmonary TB disease are immediately isolated in single rooms with negative air pressure for definite sputum smear diagnosis, particularly with three consecutive sputum or gastric aspiration analysis. After the diagnosis of smear-positive pulmonary TB is established, the patients are then transferred to another hospital that has special wards for the treatment of smear-positive pulmonary TB. Therefore, a delay in isolation on admission may spread the TB infection in-hospital. We studied 69 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with smear-positive pulmonary TB by examination of the sputum or gastric specimen.

Data collection

Data collection for each patient, collectively referred to as “patient-related factors”: age, gender, history of smoking or alcoholism, welfare recipient or not, activities of daily living, past history of TB, contact with TB patients, diabetes mellitus, other lung disease, surgical history of gastric resection, human immunodeficiency virus infection, preceding treatment with newer quinolone antibiotics, steroid use, chronic cough, loss of appetite, body mass index, body temperature on arrival, systolic blood pressure, oxygen requirement, hemoglobin level, serum albumin level, C-reactive protein level, presence of a cavitary, upper zone or disseminated lesion on the chest radiograph, and the raw score. The raw score is a validated prognostic score for patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB [8].

We also collected data on the following “facility and physician-related factors”: year of hospital visit, time of arrival (day or night), weekday or weekend arrival, the attending ER physician, medical care provided by the resident on arrival, medical care provided by male physician on arrival, and whether transferred to the hospital by ambulance.

Statistical analysis

We aimed to evaluate factors associated with delayed isolation of smear-positive pulmonary TB patients. The primary outcome measure was the duration day from hospital visit to the isolation of the patient with TB. Day-to-isolation analysis, based on the Cox proportional hazard model, was used to analyze factors associated with delay to the isolation of pulmonary TB patients. In a univariate model, the “patient-related factors” and “medical facility and physician-related factors” were evaluated as possible reasons for the delayed isolation of active pulmonary TB, based on log-rank test or univariate Cox hazard test, as appropriate. Significant factors in the univariate model were analyzed using the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were undertaken using the SPSS Statistics version 21 J (IBM, Tokyo, Japan). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the hospital (No. TGE00667-024).

Results

Sixty-nine patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB were enrolled. Base-line characteristics and univariate analysis were included in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 81 years, with 18 (26.1%) female patients. All patients were hospitalized and isolated for infection control. Two patients were discharged home, 55 were transferred to other hospitals for the treatment of TB, and 12 died in our hospital. The median length of hospital stay was 7 days with interquartile range (IQR), 5–18 days.

The median day to the isolation of pulmonary TB patients was 1 day with IQR, 1–4 days. Figure 1 showed that over 60% patients isolated within 1 day. However, approximately 10% patients isolated over 10 days (Fig. 1). On univariate analysis, male gender (p = 0.009), prior treatment with newer quinolone antibiotics (p = 0.027), absence of chronic cough (p = 0.023), appetite loss (p = 0.037), non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph (p = 0.005), lesion located other than in the upper zone on the chest radiograph (p = 0.015), and non-disseminated lesion on the chest radiograph (p = 0.028) were significant factors associated with a delayed isolation of pulmonary TB patients (Table 1).

On multivariate analysis using Cox hazard model, male gender (hazard ratio [HR], 0.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25 to 0.89; P = 0.02), absence of chronic cough (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.95; P = 0.033), and non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.92; P = 0.028) were significantly associated with delayed isolation of TB patients (Table 2).

Figure 2 showed intergroup comparisons of day-to-isolation among significant factors associated with delayed isolation of pulmonary TB patients in the multivariate analysis.

Discussion

Our study revealed that male gender, absence of chronic cough, and non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph were associated with delayed isolation of active pulmonary TB patients.

A non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph and absence of chronic cough are factors consistent with previous reports of diagnostic delay in cases of pulmonary TB; our findings of association of male gender with diagnostic delay is contrary to the findings of previous studies. Chronic cough is an important symptom for the clinician to consider the diagnosis of pulmonary TB from the clinical history. Moreover, a previous report of in-hospital diagnostic delay from Southern Taiwan revealed non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph as an independent risk factor [14], similar to our finding. A chest radiograph is commonly employed and easy to perform; presence of a cavitary lesion is critical in the early detection of pulmonary TB. In previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses, female gender has been shown to be a risk factor for delayed diagnosis of pulmonary TB [11, 12]; there are no previous reports of male gender being associated with delay in isolation of pulmonary TB patients.

We speculate that the delay in isolation associated with male gender, absence of chronic cough and non-cavitary lesion on the chest radiograph, may be related to the advanced age of our patients (mean age: 81.1 years). Younger patients with smear-positive TB were referred to other hospitals with special wards, resulting in an increase in elderly patients with TB in our hospital. Elderly patients with TB can manifest with unusual features that may be confused with aspiration pneumonia [17], commonly observed in this population [18]. The typical symptoms of aspiration pneumonia are fever, cough with sputum, and dyspnea; however, non-specific symptoms including loss of consciousness and appetite loss are also important. Thus, the symptoms of pulmonary TB and aspiration pneumonia are similar. Moreover, aspiration pneumonia, a common disease in an aging society, can co-exist in patients with active pulmonary TB and has drawn increasing attention recently [19]. Although the incidence of active pulmonary TB has decreased, the number of elderly patients has increased in Japan [20]. There may be a lack of widespread awareness among healthcare workers, including physicians, of this development. This may have led to failure to consider pulmonary TB in elderly patients. Besides, the symptoms of pulmonary TB can mimic aspiration pneumonia in the elderly.

Although previous studies have described factors associated with delayed diagnosis of pulmonary TB [11,12,13, 15, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27], we focused on factors that delayed isolation, especially among elderly patients admitted to hospital. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study that deals with delayed isolation of pulmonary TB patients in an aging society [28, 29]. According to nation-wide Japanese data, the number of patients over 70 years with smear-positive pulmonary TB has increased by 2.5 times from 1980 to 2000 [20, 30]. In an aging society, the number of older patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB may have increased in community-based acute care hospitals. However, there are few reports of elderly patients with pulmonary TB. Thus, our results may be of relevance in an aging society.

There are several limitations to our study. First, ours was based on a single center cohort study with a small sample size. The clinical ability of our residents was variable, depending on their level of training and experience, which may have led to bias. In our study model, a p < 0.05 was used as the cutoff level. This strict criteria though can prematurely exclude relevant variables, which may lead to selection bias. Second, we are unable to establish a causal relationship in this retrospective observational study. Further prospective studies are required to confirm such an association. Third, as it was a hospital-based study, we could not analyze factors involving delay from symptoms onset to hospital visit, reported as “patient delay” in a previous study [16]. Fourth, the present study may not include all in-hospital patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB, because there can be presence of the patients who discharged or died before the investigation of sputum or gastric smear.

Future research needs to be directed to understanding factors associated with a delayed diagnosis of active pulmonary TB; this information may help with earlier isolation of TB patients, improve infection control, and reduce adverse outcomes. Therefore, multi-center, prospective studies are required, across different population groups, in countries with aging populations, to corroborate our results.

Conclusion

Isolation of active pulmonary TB patients was delayed in male patients, patients without chronic cough, and patients with non-cavitary lesions on the chest radiograph. Elderly TB patients can present with atypical manifestations that mimic other diseases. Thus, physicians need to have a heightened awareness of active pulmonary TB, especially among elderly patients; this may prevent spread of infection within the hospital.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings. 2005. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5417.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2018.

Storla DG, Yimer S, Bjune GA. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:15.

Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO global surveillance and monitoring project. JAMA. 1999;282(7):677–86.

Bjune G. Tuberculosis in the 21st century: an emerging pandemic? Norsk Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):133–9.

Tuberculosis surveillance center. Tuberculosis Annual Report 2012. (1). Summary of tuberculosis notification statistics and foreign-born tuberculosis patients. Kekkaku. 2014;89(6):619–25.

Nakao M, Sone K, Kagawa Y, et al. Diagnostic delay of pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with aspiration pneumonia: two case reports and a mini-review from Japan. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(2):835–9.

Fukushima Y, Shiobara K, Shiobara T, et al. Patients in whom active tuberculosis was diagnosed after admission to a Japanese university hospital from 2005 through 2007. J Infect Chemother. 2011;17(5):652–7.

Horita N, Miyazawa N, Yoshiyama T, et al. Development and validation of a tuberculosis prognostic score for smear-positive in-patients in Japan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(1):54–60.

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2017_main_text.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2018.

Golub JE, Bur S, Cronin WA, et al. Delayed tuberculosis diagnosis and tuberculosis transmission. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(1):24–30.

Cai J, Wang X, Ma A, Wang Q, Han X, Li Y. Factors associated with patient and provider delays for tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120088.

Li Y, Ehiri J, Tang S, et al. Factors associated with patient, and diagnostic delays in Chinese TB patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:156.

Chen TC, Lu PL, Lin CY, Lin WR, Chen YH. Fluoroquinolones are associated with delayed treatment and resistance in tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(3):e211–6.

Lin CY, Lin WR, Chen TC, et al. Why is in-hospital diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis delayed in southern Taiwan? J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109(4):269–77.

Yimer S, Bjune G, Alene G. Diagnostic and treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:112.

Chiang CY, Chang CT, Chang RE, Li CT, Huang RM. Patient and health system delays in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in southern Taiwan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(9):1006–12.

Yoshikawa TT. Tuberculosis in aging adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(2):178–87.

Teramoto S, Fukuchi Y, Sasaki H, Sato K, Sekizawa K, Matsuse T. High incidence of aspiration pneumonia in community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: a multicenter, prospective study in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(3):577–9.

Ubukata S, Jingu D, Yajima T, Shoji M, Takahashi H. Occurrence and clinical characteristics of tuberculosis among home medical care patients. Kekkaku. 2014;89(7):649–54.

Ohmori M, Ishikawa N, Yoshiyama T, Uchimura K, Aoki M, Mori T. Current epidemiological trend of tuberculosis in Japan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(5):415–23.

Basnet R, Hinderaker SG, Enarson D, Malla P, Morkve O. Delay in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:236.

Meyssonnier V, Li X, Shen X, et al. Factors associated with delayed tuberculosis diagnosis in China. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23(2):253–7.

Gagliotti C, Resi D, Moro ML. Delay in the treatment of pulmonary TB in a changing demographic scenario. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(3):305–9.

Liam CK, Tang BG. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in patients attending a university teaching hospital. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1(4):326–32.

Rajeswari R, Chandrasekaran V, Suhadev M, Sivasubramaniam S, Sudha G, Renu G. Factors associated with patient and health system delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(9):789–95.

Sreeramareddy CT, Qin ZZ, Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Pai M. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(3):255–66.

Xu B, Jiang QW, Xiu Y, Diwan VK. Diagnostic delays in access to tuberculosis care in counties with or without the National Tuberculosis Control Programme in rural China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(7):784–90.

Severin J, Ruhe-van der Werff S, Bakker M, Vos MC. Risk factors for delayed isolation of tuberculosis patients in a tertiary care hospital in a low-incidence country. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4(Suppl 1):93.

Hsieh MJ, Liang HW, Chiang PC, et al. Delayed suspicion, treatment and isolation of tuberculosis patients in pulmonology/infectious diseases and non-pulmonology/infectious diseases wards. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(3):202–9.

Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association. Statistics of tuberculosis 2001. Tokyo: JATA; 2001.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS and TS conceived the idea of the work and collected data. NS performed the analysis. NS and TY interpreted the results, KI supervised throughout the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shonan Kamakura General Hospital (No. TGE00667-024). For the retrospective study, we announced officially by the hospital web-site and the signboard in hospital. All participants didn’t reject the consent for our study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishiguchi, S., Tomiyama, S., Kitagawa, I. et al. Delayed isolation of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in a Japanese acute care hospital. BMC Pulm Med 18, 94 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0653-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0653-1