Abstract

Background

Those affected by advanced fibrotic interstitial lung diseases have limited treatment options and in the terminal stages, the focus of care is on symptom management. However, quantitatively, little is known about symptom prevalence. We aimed to determine the prevalence of symptoms in Progressive Idiopathic Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease (PIF-ILD).

Methods

Searches on eight electronic databases including MEDLINE for clinical studies between 1966 and 2015 where the target population was adults with PIF-ILD and for whom the prevalence of symptoms had been calculated.

Results

A total of 4086 titles were screened for eligibility criteria; 23 studies were included for analysis. The highest prevalence was that for breathlessness (54–98%) and cough (59–100%) followed by heartburn (25–65%) and depression (10–49%). The heterogeneity of studies limited their comparability, but many of the symptoms present in patients with other end-stage disease were also seen in PIF-ILD.

Conclusions

This is the first quantitative review of symptoms in people with Progressive Idiopathic Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases. Symptoms are common, often multiple and have a comparable prevalence to those experienced in other advanced diseases. Quantification of these data provides valuable information to inform the allocation of resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

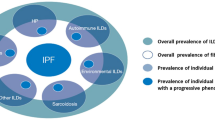

Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease have a wide range of diagnoses and prognoses. Many patients can live many years with their diagnosis and some are responsive to treatments. However, a subset of patients with Progressive Idiopathic Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases (PIF-ILD) such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have a short disease trajectory and a similar prognosis to people with lung cancer [1]. The clinical manifestation of advanced fibrotic Non Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP) is similar to IPF [2]. It is important to differentiate NSIP from IPF in the early stages when the disease is potentially responsive to therapy [2] .However, when the disease is advanced and irreversible, this becomes less important and the focus should be on symptom control.

The United Kingdom (UK) End of life care strategy aimed to promote high quality care for all adults at the end of life [3]. In addition, the British Thoracic [4] and NICE idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis guidance [5] emphasize the importance of a proactive approach in managing symptoms.

Recent qualitative work in this group has shown uncontrolled symptoms, for example, shortness of breath, cough and insomnia, which impact on every aspect of patients and carers lives [6, 7]. However, quantitative work assessing prevalence of symptoms is limited and there has been no systematic review of this literature. Synthesising the quantitative evidence for symptom prevalence for this group will add to previous qualitative work, raise awareness of these symptoms and focus clinical intervention.

Methods

Aim

To estimate the symptom prevalence in people with PIF-ILD.

Design

Systematic review of the literature.

Search strategy

We performed comprehensive searches of databases including MEDLINE, Cochrane, EMBASE, Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Knowledge), pre-Medline, CINAHL and PSYCINFO from 1966 to November 2013 using a combination of MESH headings and keywords (for full search strategy see online Additional file 1 APPENDIX A). In addition, key journals hand searched included THORAX, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine and CHEST (2000 to 2013). The search was updated to March 2015. Only studies in English or Spanish were included.

Selection

Study population

Published data of adults (≥ 18 years old), with all stages of the following ILD types: interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia from any setting were included.

Studies in which patients had COPD and/or cancer in addition to PIF-ILD were excluded.

Types of studies included

A scoping search identified a paucity of data. Therefore all study types reporting quantitative data were included. Case reports of fewer than five patients were excluded. Qualitative studies were included if quantitative data were available for extraction.

Types of outcomes included

Symptoms included were based on a previous systematic review looking at interventions to improve symptoms and quality in patients with PIF-ILD [8] and encompassed both physical and psychological domains.

Data extraction

One independent reviewer (SC) selected the studies against the inclusion criteria using the title and, if the title did not offer enough information, abstracts and/or full text were read. Data were extracted using a form that included the main author, year of publication, setting, type and number of participants, disease group, aims of the study, study design, measurement methods and prevalence of individual symptoms (See Additional file 2 APPENDIX B).

Data analysis

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement checklist for observational studies [9] was used to appraise each of the final studies. A palliative symptom grid was used and the number of patients in each study was calculated for each of the symptoms. Meta-synthesis and descriptive statistics were used for analysis and to present the findings. Where appropriate, a meta-analysis of each symptom from multiple studies was conducted using a random-effects model with inverse-variance weighting. Symptoms which were reported in only two studies or less were excluded from the meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was also quantified using the I-squared measure [10]. The confidence intervals are based on exact binomial (Clopper-Pearson) procedures [11]. Meta-analysis was conducted in Stata (StataCorp 2015) release 14 [12].

Results

Overview of included studies

Twenty-three articles describing symptoms were selected for this review (see Fig. 1) potentially relevant but excluded studies have been listed separately in Additional file 3 APPENDIX C. Included studies represented N = 3171 patients from European, Asian, and North and South American countries, conducted on outpatients at different disease stages; four studies included patients with end-stage disease [13,14,15,16]. The mean age across all studies varied between the fifth and sixth decade of life, and one study included patients older than 65 years [17]. Overall, studies found prognosis ranged between 12.9 to 46 months from time of diagnosis.

Study designs varied with a variety of retro and prospective designs (Table 1).

Symptom prevalence

Respiratory symptoms such as breathlessness and cough were measured in 13 studies [14, 15, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]; fatigue and weight loss in five [18, 19, 21, 24, 28]; digestive tract symptoms in eight [13,14,15,16, 19, 20, 29, 30] sleep disorder in four [19, 28, 31, 32]; and other symptoms such as pain and urinary tract disorders in five [19,20,21, 24, 29]. The incidence of depression and/or anxiety was calculated in four studies [19, 33,34,35]. No studies documented delirium, constipation, halitosis, hemoptysis, hiccups, hyperphagia, polydipsia or mouth problems. A summary of findings is presented in Fig. 2.

Respiratory symptoms

The overwhelming majority of patients had breathlessness (68.2–98%) and cough (59–94%) [14, 15, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. These were not only common symptoms, but preceded diagnosis by 6.8 months to 4 years [18]. Only one study documented breathlessness using the modified Medical Research Council scale (mMRC) (range 0 to 4) in 45.3% of the participants [17]. Nearly one in ten (9.3%) had mMRC grade 4. Severe breathlessness was associated with poor prognosis and those with mMRC scale score 3 and 4 had a median survival of 0.5 years [17].

Depression

A variety of depression measurement tools were used to provide prevalence estimates of depression ranking between 10% [34] and 49.2% [19, 33, 35]. A worse depression score was found to be associated with reduced Forced Expiratory Volume (FEV), Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), gas transfer factor and gas constant, increased duration of diagnosis, greater number of comorbidities [33]; worse breathlessness severity, pain severity, sleep quality, 4-m walk time, grip strength and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) [35].

The prevalence of anxiety was estimated to be as high as 58% in one study of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and symptom burden [34].

Digestive tract symptoms

Upper gastro-intestinal symptoms are described in IPF and have been investigated in several studies. Gastro-oesophageal reflux prevalence was shown in 35.7 to 100% [13,14,15,16, 20, 30].

Although in some patients this appeared to be asymptomatic, symptoms were reported by a significant proportion: belching (51%) [29], regurgitation (16–40%) [13,14,15,16, 20, 29], heartburn (29–48%) [13,14,15,16, 20, 29], dysphagia (11–43%) [13, 16, 20, 29, 30], and dysphonia (11%) [20]. Typical acid reflux symptoms were found [13,14,15, 20] and usually related to other causes such as cough (83% in these studies). A correlation between cough and acid reflux in the oesophagus was seen in 28% of the episodes of reflux [25]. However, 33% of those without evidence of dysmotility had at least one oesophageal symptom [20].

Sleep related symptoms

A relationship between obstructive sleep apnoea and IPF was observed in a 50 patients study with stable breathlessness, which a quarter of participants had an Epworth sleepiness score higher than 10 representing significant daytime sleepiness [31]. In one study of 30 patients, the following sleep related symptoms were reported: insomnia (46.6%), snoring (40%), excessive daytime sleepiness (20%), and witnessed apnoea’s (13.3%) [32]. Studies used variety of outcome measures and showed problems with daytime fatigue (The Functional Systems Scores (FSS)), daytime dysfunction (Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ)) and poor sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)). Patients reported excessive daytime sleepiness (77.7%), snoring (88%), daytime fatigue (29%), witnessed apnoeas (44.4%), and insomnia (6–46%) [19, 28, 31, 32].

Anorexia, weight loss, fatigue

The prevalence of weight loss was estimated as 2–18% (out of N = 151), and the prevalence of fatigue as 7.6–29% out of N = 240 [18, 19, 21, 24, 28].

Pain

Non-specified pain was found in 9% of the population, while chest pain affected 6–29% [19,20,21, 24, 29]. Two studies found epigastric pain in 18 and 91% of the population [20, 30].

Other symptoms

A prevalence of polyuria/polydipsia prevalence of 4% was found in one study [19].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to draw together the symptom profile of people with PIF-ILD and shows a wide array of symptoms; comparable with those reported in other advanced diseases [36] (see Table 2). Breathlessness is seen to be a major problem, as prevalent as for people with COPD and heart disease. Likewise, psychological problems (depression and anxiety) and insomnia are prevalent in PIF-ILD. However, given the comparable high prevalence of both breathlessness, anxiety and sleep disturbance, the estimate for daytime fatigue was surprisingly low [28]. This may be explained, at least in part, by the different outcome measures used to assess sleep quality in the different studies and only one study accounted for comorbid conditions that might interfere with sleep quality and quality of life [28].

Two other symptoms stand out as particular problems for people with PIF-ILD. Firstly, cough is identified as not only highly prevalent, but also of major significance in terms of symptom burden, often preceding the diagnosis by some time. Secondly, although reports of nausea and vomiting are relatively low, there are significant problems associated with gastro-intestinal dysmotility leading to reflux which is likely to aggravate cough and may be associated with chest/epigastric pain.

Most people with respiratory disease have multiple co-morbidities which contribute long- term symptoms [37]. In addition, symptoms do not occur in isolation with demonstrated interactions between many symptoms, particularly in lung cancer, where a respiratory distress cluster of cough, breathlessness and fatigue has been described [38, 39]. The possibility of specific symptom clusters (clinically observed symptoms associations) for PIF-ILD which could benefit from a combined symptomatic approach is an area for further research. Knowledge of symptom clusters in PIF-ILD may help prompt clinical investigation of associated symptoms when one symptom is detected. It is clear from these data that a single symptom does not occur in isolation. Therefore is important that symptom assessment in people with PIF-ILD should focus on all commonly encountered symptoms and not just breathlessness alone. The significant prevalence of anxiety, depression and social isolation as the disease progresses highlights the importance of a holistic approach embodied by palliative care [6].

Palliative care is the active, total care of people with advanced, progressive disease [40]. Currently, the vast majority of palliative care services are provided to patients with cancer, and access to specialist palliative care is inconsistent for people with non-malignant disease. This inequity has been highlighted in the recent NICE guidance for IPF [5]. These stated that the ILD specialist services should have the skills to assess and manage most supportive and palliative care needs of the people under their care. In addition, robust joint working and pathways of care should also be in place to ensure access to specialist palliative care for those issues that the ILD services are unable to address. However, this policy has been largely unimplemented, and in everyday practice as currently configured, patients have unmet palliative care needs [7, 41].

Implications for clinical practice and research

People with PIF-ILD face a sombre prognosis and deterioration in their quality of life with little hope of successful disease modification. Therefore, improvement in quality of life and palliation of significant symptoms are crucially important treatment goals [5, 42]. Recognition that these are prevalent is the first step, the next is to incorporate systematic assessment of symptoms and other palliative care concerns as a routine part of clinical management by respiratory health professionals. There needs to be a recognition that other symptoms alongside breathlessness are present. This is likely to have implications for education and training needs, extended team working between respiratory, palliative and primary care, and service configuration. Validated clinical tools to aid the clinician to identify and triage symptoms and other needs are needed for everyday practice and has been highlighted in the recent NICE quality standard for IPF [42]. An example of such tool is the recently adapted and validated Needs Assessment Tool-Interstitial Lung Disease (NAT-ILD) [43].

Good quality prospective observational studies are needed to get better estimates of symptom prevalence in PIF-ILD over the duration of the disease. Such prospective evaluation would allow investigation of symptoms not found in this review such as confusion, constipation and anorexia. In particular, the natural history of symptoms as the disease progresses to advanced disease and end of life along with the impact upon the individual and their family needs to be described in order to be able to understand the clinical care needs of this patient group, inform palliative and supportive care service planning and to inform study designs for clinical trials of symptom interventions. To facilitate this, disease severity with baseline lung function should be published for all studies.

Symptoms which seem to be of particular concern to people with PIF-ILD such as cough and gastro-intestinal dysmotility are under-researched and deserve focus. In addition, validation of questionnaires to determine the presence of conditions such as depression and fatigue in this group would be useful.

Limitations

Only one reviewer screened, selected and extracted data from the articles included. Those not published in the English or Spanish language were excluded. Grey literature was not searched. It was difficult to give an accurate estimate of symptom prevalence due to the varying quality of cohort formation, measurement tools and definition of the symptom in question. Period prevalence time ranges, varying definitions of symptoms, sample size proportions and the various different measurement methods across the studies may all have contributed to variations in the minimum and maximum prevalence ranges. Due to the heterogeneity of the study populations and poor reporting, meta-analyses and sub-analyses by disease and severity of disease was not possible. Patients included in these studies had stable disease and were not receiving oxygen therapy.

Conclusion

This study aimed to determine from existing studies, the prevalence of a group of symptoms in patients with PIF-ILD. Symptoms are common, often multiple and have a comparable prevalence to those experienced by people with other advanced diseases. Symptoms extend far beyond respiratory symptoms such as breathlessness and cough, and include fatigue, sleep disturbance as well as a broad variety of gastrointestinal symptoms. Breathlessness and anxiety are as prevalent as in COPD and heart disease, yet patients rarely have access to breathlessness management programs. Cough and gastrointestinal dysmotility appear to be particular issues for people with PIF-ILD and warrant further work which should include exploration of a possible PIF-ILD symptom clusters.

Quantification of these symptoms provide valuable information to inform the education and training needs of ILD services to allow routine assessment and management by ILD clinicians and appropriate use and allocation of specialist palliative care resources.

These findings highlight and support the need for a systematic and validated approach to assessment of symptoms in every day clinical practice by ILD services. This would ensure close attention to symptom management with appropriate and timely referral to palliative care services according to need, in order to optimise quality of life and provide good care during advanced disease and end of life.

Abbreviations

- DLco:

-

Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

- FEV:

-

Forced Expiratory Volume

- FOSQ :

-

Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

- FSS:

-

Functional Systems Scores

- FVC:

-

Forced Vital Capacity

- HRQoL :

-

Health-related quality of life

- mMRC:

-

Modified Medical Research Council scale

- MPA:

-

Microscopic polyangiitis

- NAT-ILD :

-

Needs Assessment Tool-Interstitial Lung Disease

- NSIP:

-

Non Specific Interstitial Pneumonia

- PIF-ILD :

-

Progressive Idiopathic Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease

- PSQI :

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

References

Vancheri C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer: do they really look similar? BMC Med. 2015;13(1):220.

du Bois R, King TE Jr. Challenges in pulmonary fibrosis x 5: the NSIP/UIP debate. Thorax. 2007;62(11):1008–12.

Richards M. The End of Life Care Strategy: Promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. End of Life Care Strategy; 2008.

Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, Greaves MS, Hansell DM, Harrison NK, et al. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63(Suppl 5):v1–58.

Excellence NIfHaC. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the diagnosis and management of suspected idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 2013.

Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, Wells AU, Birring SS, Riley J, et al. The palliative care needs for fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a qualitative study of patients, informal caregivers and health professionals. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):869–76.

Sampson C, Gill BH, Harrison NK, Nelson A, Byrne A. The care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their carers (CaNoPy): results of a qualitative study. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15(1):1.

Bajwah S, Ross JR, Peacock JL, Higginson IJ, Wells AU, Patel AS, et al. Interventions to improve symptoms and quality of life of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature. Thorax. 2013;68(9):867–79.

Knottnerus A, Tugwell P. STROBE--a checklist to strengthen the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):323.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857–72.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. 14th ed. College Station: StatCorp LP; 2015.

D'Ovidio F, Singer LG, Hadjiliadis D, Pierre A, Waddell TK, de Perrot M, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in end-stage lung disease candidates for lung transplant. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(4):1254–60.

Hoppo T, Komatsu Y, Jobe BA. Su1529 is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis really idiopathic?: patterns of reflux analyzed by bi-positional high-resolution manometry and Hypopharyngeal multichannel intraluminal impedance. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):S-1056.

Patti MG, Tedesco P, Golden J, Hays S, Hoopes C, Meneghetti A, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: how often is it really idiopathic? J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9(8):1053–6. discussion 6–8

Sweet MP, Patti MG, Leard LE, Golden JA, Hays SR, Hoopes C, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis referred for lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(4):1078–84.

Araki T, Katsura H, Sawabe M, Kida K. A clinical study of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis based on autopsy studies in elderly patients. Intern Med. 2003;42(6):483–9.

Alhamad EH, Masood M, Shaik SA, Arafah M. Clinical and functional outcomes in middle eastern patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Respir J. 2008;2(4):220–6.

Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, Wells AU, Birring SS, Patel A, et al. Specialist palliative care is more than drugs: a retrospective study of ILD patients. Lung. 2012;190(2):215–20.

Bandeira CD, Rubin AS, Cardoso PF, Moreira Jda S, Machado Mda M. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(12):1182–9.

Hashemi Sadraei N, Riahi T, Masjedi MR. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a referral center in Iran: are patients developing the disease at a younger age? Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(3):177–81.

Jeon K, Chung MP, Lee KS, Chung MJ, Han J, Koh WJ, et al. Prognostic factors and causes of death in Korean patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med. 2006;100(3):451–7.

Ohno S, Nakaya T, Bando M, Sugiyama Y. Nationwide epidemiological survey of patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias using clinical personal records. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;45(10):759–65.

Schoenheit G, Becattelli I, Cohen AH. Living with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an in-depth qualitative survey of European patients. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8(4):225–31.

Tobin RW, Pope CE 2nd, Pellegrini CA, Emond MJ, Sillery J, Raghu G. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(6):1804–8.

Von Plessen C, Grinde Ø, Gulsvik A. Incidence and prevalence of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in a Norwegian community. Respir Med. 2003;97(4):428–35.

Huang H, Wang YX, Jiang CG, Liu J, Li J, Xu K, et al. A retrospective study of microscopic polyangiitis patients presenting with pulmonary fibrosis in China. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:8.

Mermigkis C, Chapman J, Golish J, Mermigkis D, Budur K, Kopanakis A, et al. Sleep-related breathing disorders in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung. 2007;185(3):173–8.

Raghu G, Freudenberger TD, Yang S, Curtis JR, Spada C, Hayes J, et al. High prevalence of abnormal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(1):136–42.

Aksu O, Songur N, Songur Y, Ozturk O, Adiloglu AK, Kapucuoglu N, et al. Is gastroesophageal reflux contribute to the development chronic cough by triggering pulmonary fibrosis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25(Suppl 1):48–53.

Lancaster LH, Mason WR, Parnell JA, Rice TW, Loyd JE, Milstone AP, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is common in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2009;136(3):772–9.

Mermigkis C, Stagaki E, Amfilochiou A, Polychronopoulos V, Korkonikitas P, Mermigkis D, et al. Sleep quality and associated daytime consequences in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18(1):10–5.

Akhtar AA, Ali MA, Smith RP. Depression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chron Respir Dis. 2013;10(3):127–33.

Lindell KO, Olshansky E, Song M, Zullo TG, Gibson KF, Kaminski N, et al. Impact of a disease-management program on symptom burden and health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their care partners. Heart Lung. 2010;39(4):304–14.

Ryerson CJ, Arean PA, Berkeley J, Carrieri-Kohlman VL, Pantilat SZ, Landefeld CS, et al. Depression is a common and chronic comorbidity in patients with interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2012;17(3):525–32.

Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;31(1):58–69.

Currow DC, Clark K, Kamal A, Collier A, Agar MR, Lovell MR, et al. The population burden of chronic symptoms that substantially predate the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(6):480–5.

Molassiotis A, Lowe M, Blackhall F, Lorigan P. A qualitative exploration of a respiratory distress symptom cluster in lung cancer: cough, breathlessness and fatigue. Lung Cancer. 2011;71(1):94–102.

Dodd MJ, Miaskowski C, Paul SM, editors. Symptom clusters and their effect on the functional status of patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum; 2001.

WHO. Definition of palliative care: World Health Organisation. 2002 [Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

Bajwah S, Ross JR, Wells AU, Mohammed K, Oyebode C, Birring SS, et al. Palliative care for patients with advanced fibrotic lung disease: a randomised controlled phase II and feasibility trial of a community case conference intervention. Thorax. 2015;70(9):830–9.

Excellence NIfC. NICE. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in adults Quality Standard. Quality standard for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis DRAFT. In: NICE, editor. Manchester: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs79/resources/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis-in-adults-pdf-2098856506309. Accessed May 2018.

Boland JW, Reigada C, Yorke J, Hart SP, Bajwah S, Ross J, et al. The adaptation, face, and content validation of a needs assessment tool: progressive disease for people with interstitial lung disease. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(5):549–55.

Funding

This systematic review was self-funded by SC who completed it as part of a MSc in Palliative Care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC and SB conceived the idea for the review. SC drafted the original review. CR, MJ and SB adapted the review into a paper for publication. MD conducted analysis. All authors reviewed the final version and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required for this study as it was a systematic review.

Consent to participate was not required.

Competing interests

The authors declares that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Appendix A Full search strategy – Medicine search strategy. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 2:

Appendix B Data extraction form. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 3:

Appendix C Potentially Relevant but Excluded Studies. (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Carvajalino, S., Reigada, C., Johnson, M.J. et al. Symptom prevalence of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulm Med 18, 78 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0651-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0651-3