Abstract

Background

No systemic evaluation of asthma control in Jilin Province has been reported. Asthma control might provide the basis for asthma management in this region. A multicenter hospital-based cross-sectional study was performed to investigate the asthma control and related factors for severe asthma exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe asthma in Jilin Province, China.

Methods

The study enrolled 1546 patients in five grade one general hospitals from January to December 2013. Asthma medication, patient self-management, asthma control test (ACT) scores and frequency of severe asthma exacerbations during the follow-up (12 months) were collected via a follow-up questionnaire.

Results

In the study, 889 patients provided a complete follow-up questionnaire. Severe asthma exacerbations occurred in 54.89 % of patients. ACT score ≤15, asthma medication ≤ 3 months, severe asthma, income level lower than average Per Capita Disposable Income (PCDI) and a lower educational level were risk factors of a severe exacerbation.

Conclusions

Poor adherence to asthma medication, poor asthma symptom control, lower income, a low educational level might be possible reasons for the high incidence of severe asthma exacerbations and poor asthma control in Jilin Province of China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is a common disease of airway inflammation with a high prevalence worldwide [1]. Asthma control refers to coming to a steady state after treatment. It has been reported that asthma has not been well-controlled in a large number of asthma patients, as defined by international guidelines [2–4]. A multicenter study of 10 large developed cities in China has reported that 28.7 % and 45.0 % of asthmatic patients achieve full and partial control, respectively, according to the guidelines of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) [5]. However, the data is not sufficient for evaluating the asthma control in China, because China is a large country in which the socioeconomic status, medical insurance coverage, climate and living environments vary considerably between different regions. All of these factors might influence asthma control. Therefore, additional studies on asthma control in different regions of China are needed.

Jilin Province is located in the northeast region of China and characterized by a cold climate, relatively low gross domestic product (GDP) and slow economic development. Until recently, there is few data on asthma control and risk factors for severe asthma exacerbations in Jilin Province. This study aimed to provide useful information in this field. In addition to asthma control test (ACT) questionnaire, we also investigated frequencies of asthma exacerbations. Because there is rare data on risk factors of asthma in China, the study also analyzed the effect of adherence, application of asthma medicine, severity and socioeconomic status on asthma control in Jilin Province so as to further explore the risk factors of asthma in China. This survey will provide useful guidelines for preventing and managing asthma in Jilin Province, China.

Methods

Study design and patients

In this multi-center cross-sectional study, 1546 asthmatic patients were enrolled consecutively, who were hospitalized in five general hospitals with grade three in Jilin Province from January 2013 to December 2013.

The patient inclusion criteria were as follow: older than 18 years old; moderate asthma or severe asthma based on the GINA criteria (2012) [6] (that require high intensity treatment to maintain good control or where good control is not achieved despite high intensity treatment); longer than 1 month of diagnosed asthma; longer than 1 year of local residence. Patients with the following diseases were excluded from the survey: severe irreversible organ failure, such as heart, renal and liver failure; severe cerebrovascular disease with concomitant consciousness disturbance; advanced cancer; bronchiectasis; pulmonary embolism; interstitial lung disease; or active tuberculosis. Patients who were unable or unwilling to participate in the survey because of mental or neurological disorders were also excluded. The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Hospital of Jilin University. Each patient gave their written informed consent before the survey.

According to the configuration and the ability of the hospital, hospitals in China are classified into grade one hospitals (primary hospitals providing basic health care in communities), grade two hospitals (secondary hospitals affiliated with a medium-size city or district), grade three (comprehensive or general hospitals providing specialist health services, medical education, and scientific studies), and village clinics/community health station [7]. The five hospitals with grade three in the study were the Second Hospital of Jilin University, First Hospital of Jilin University, Jilin Province Hospital, 208th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University. These hospitals covered the majority of the geographic regions of Jilin Province. The reason why we enrolled patients with moderate to severe asthma from five hospitals with grade three was that physicians in hospitals with grade three in China have been trained comprehensively about GINA, and could diagnose and educate asthmatic patients correctly, thus the incidence of misdiagnosis and mistreatment would be minimized.

Survey questionnaire and data collection

Demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical data were collected from hospital medical records. The demographic and socioeconomic data included age, gender, residence, education, occupation, medical insurance type and smoking history. Residence referred to rural or urban residence in China. In Jilin Province, the medical insurance mainly included Jilin provincial insurance (reimbursement ratio ≥80 %), city insurance-civil servants, retirement, employee (reimbursement ratio 70–80 %), city insurance-urban dweller (reimbursement ratio 50–70 %), New Rural Cooperative Medical Insurance (NRCMI, reimbursement ratio 30–50 %) and commercial medical insurance. The clinical data included asthma severity, FEV1 before discharge, hospital duration, atopic status (with clear allergic history or positive specific IgE or positive skin prick test), complications and comorbidities during the hospitalization. The complications and comorbidities consisted of allergic rhinitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, respiratory failure, circulation system disease (pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale, hypertension, coronary heart disease and other heart diseases), nervous system disease, and digestive system disease (e.g., gastro-esophageal reflux disease, gastritis, digestive ulcers). Regular use of ICS (inhaled corticosteroid)/[ICS + LABA (Long-acting beta agonist)]/[ICS+ long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA)] and asthma- associated education from a doctor during hospitalization were also included in clinical data.

Asthma control status and asthma medication during the first 12 months after discharge were collected via a follow-up questionnaire that was completed during each clinical visit (once every 3 months). During the visit, physicians asked the patients the questionnaire and filled in the answers. Review with a physician at least once every three months was defined as regular review or else defined as irregular review. The follow-up questionnaire included questions on several topics. (1) Household income. Because the Per Capita Disposable Income (PCDI) in Jilin Province in 2013 was reported to be 22274.60 Ren min bi (RMB) by the official data from Statistics Department (http://data.stats.gov.cn/), the income levels of the patients were classified into two groups: ≥PCDI group and < PCDI group. Residence referred to rural or urban residence. (2) Self-management of patients included the following information: regularity of a review, and regularity of writing in an asthma diary. (3) Performance of a pulmonary function test (once every three months) and peak flow meter (PFM) utilization. (4) Asthma medication, including the following information: types of medicines, time course of treatment, regularity of application of these medicines, and the reasons for using ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) ≤3 months. (5) ACT scores. In addition to the patient-assessed level of control, ACT questionnaire consisted of four questions concerning symptoms or relief [8]. Based on previous studies [8, 9], the ACT scores were evaluated as follows: ≥20, well-controlled asthma; 16–20, partially controlled asthma; and 5–15, poorly controlled asthma. (6) ACT scores were the mean value of twice testing results, which were completed in the middle and end of follow up year by each patient. A severe asthma exacerbation was defined as hospitalization and emergency department visit because of asthma [10]. The study was conducted in the same way among all institutes.

Statistical analysis

This study used IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 software (IBM, Somers, NY, USA) to conduct the statistical analyses. Data were presented as mean ± SD or percentage. A Chi-square test was used to perform a univariate analysis between demographic and clinical factors, and severe asthma exacerbations. A multivariate analysis was conducted using binary logistic regression (Forward: LR), with the significant factors identified from the univariate analysis. Factors were considered significant at p-value <0.05. The association was displayed as odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). A correlation between the ACT score and the frequency of severe exacerbations in asthma patients was tested using a Spearman Correlation Coefficient. Differences with a p-value <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics and clinical date of patients

Collectively, 1546 patients with moderate or severe asthma were enrolled in the study. Their mean age was 55.8 ± 16.8 years old. Baseline characteristics of the patients were shown in Table 1. Approximately 26.9 % of the patients were rural residents, 59.31 % were female patients, 31.82 % possessed middle school and lower education, and 97.67 % had a medical insurance. Former and current smokers were 39.78 % and 9.96 %, respectively.

Clinical data of the patients during the hospitalization were summarized in Table 2. The hospital duration was longer (10.15 ± 6.23 days). During the hospitalization, the ratio of the patients received systemic asthma-associated education and treatment with ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) were higher (95.34 %, 92.24 %). Meanwhile, asthma patients got high morbidity rate of complication (81.18 %).

Asthma control, asthma medication and severe asthma exacerbations during a 12-month follow-up after discharge

Of the 1546 patients, 889 patients provided a complete follow-up questionnaire. The other 657 patients could not answer all of the questions on the questionnaire because of death (57 cases), personal reasons or unknown causes.

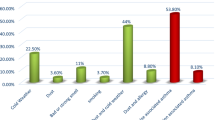

Follow-up data (Table 3) on asthma control, asthma medication and severe asthma exacerbations revealed that 36.33 % of the patients lived with an income below the average PCDI, and only 8.66 % kept in touch with physicians and reviewed regularly. The percentage of patients taking a pulmonary function test, utilizing PFM and writing in an asthma diary regularly were 7.87 %, 3.60 % and 5.29 %, respectively. Only 38.47 % of the patients took ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) regularly for longer than 3 months after discharge regardless of whether they had received asthma education or not. The percentage of patients with an unsatisfactory syndrome control (ACT scores ≤ 20) in Jilin Province was 71.88 %. Severe asthma exacerbations occurred in 54.89 % of the patients, and 11.59 % were admitted to the hospital again within 12 months of discharge. Moreover, ACT scores (it were the mean value of twice testing results, which were completed in the middle and end of follow up year by each patient) were negatively correlated with the frequencies of severe asthma exacerbations (r = −0.716, p < 0.001, Fig. 1).

Risk factors for severe asthma exacerbations in the follow-up period

A univariate analysis was performed to explore the risk factors of severe asthma exacerbations (Table 4). The multivariate analysis with a binary logistic regression (Forward: LR) was applied to exclude the mutual interference between the risk factors. Nine risk factors were identified for severe asthma exacerbations in Jilin Province (Table 5). The use of ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) ≤ 3 months was the greatest risk factor for severe asthma exacerbations. The risk factor for poor adherence to treatment was further analyzed. Lower income and education, medical insurance with low reimbursement ratio, female, elderly, and following up irregularly were risk factors for usage of ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) ≤ 3 months (Table 6).

Discussion

It was the first multicenter hospital-based cross-sectional study to comprehensively investigate status of asthma control and risk factors for severe asthma exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe asthma in Jilin Province in northeast China. Based on the ACT scores, the current study found good asthma control in 31.61 % of the patients with moderate or severe asthma; partial asthma control in 40.27 %; and poor asthma control in 28.12 %. The percentage of the patients with severe asthma exacerbations during the follow-up period was 54.89 %. These findings suggest unsatisfactory asthma control. Moreover, the study found that the ACT scores were negatively correlated with the frequency of severe asthma exacerbations during the follow-up period, and ACT scores ≤ 15 was identified as an important risk factor for severe asthma exacerbations. The finding was in accordance with the data presented by Haselkorn T [11]. The differences between ACT scores and frequency of severe asthma exacerbations were that ACT scores were often required from the patient's subjective feeling, and revealed four recent weeks of asthma control rather than one year.

Poor adherence was shown in our study. Only 38.4 % of the patients continued their medication for more than 3 months after discharge, and only 8.66 % of the patients were reviewed regularly by physicians, which is lower than the data found in a study conducted in USA [12]. The study also showed that within one year after discharge, severe asthma, rural and poor patients tended to have lower ACT scores and higher frequencies of severe asthma exacerbations.

Asthma control assessments contain symptom control assessment and risk factor assessment. It has been reported that overestimating asthma control based on ACT scores will result in inadequate treatment or even termination of medication [13–15]. Thus, we not only studied ACT scores, but also investigated the frequency and risk factors of severe asthma exacerbations in the patients in the current study. The use of ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) ≤ 3 months was found to be the greatest risk factor for severe asthma exacerbations, which was in line with previous findings [16–19]. In addition to ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) ≤ 3 months, the study found that ACT scores ≤15, asthma severity, a junior high school and lower educational level, an income level lower than PCDI, hospital days ≥15 days, rural residence and FEV1 ≤ 50 % predicted were also risk factors for severe asthma exacerbations. Previous studies have reported that FEV1 < 60 % predicted is a risk factor for exacerbations [20, 21]. However, the study found that FEV1 < 50 % predicted was a more significant criterion than FEV1 < 60 % predicted for severe asthma exacerbations. This difference might be attributed to the fact that the pulmonary function testing has primarily been conducted in convalescence, immediately following an acute exacerbation, when pulmonary function is not totally recovered. In the study, 71.48 % of the patients who did not take the ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) for more than 3 months complained that the medicines were too expensive (300–600 RMB per month). Our study revealed that lower income and education, and medical insurance with low reimbursement ratio were main risk factors for poor adherence of asthma treatment, and 71.48 % of patients stopped the therapy of ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA) ahead of schedule, due to expensive price of medicines. So reduced out-of-pocket expenses [22] or free drugs may improve medication adherence from the government level. Otherwise, 45.89 % of asthma patients used other drugs to instead of ICS/(ICS + LABA)/(ICS + LAMA), for example theophylline, which has been recently shown to have antiinflammatory effects in asthma at lower concentrations, is used commonly in China for cheaper price [23]. Meanwhile, some traditional Chinese medicine had been used irregularly. So a multi-center, cross-sectional study about certain cheaper drugs for asthma control to improve adherence to self-administered medications should be designed well in further.

These findings suggested that lower socioeconomic and educational levels and limited reimbursement from insurance were the primary obstacles to regularly using their asthma medicine. These were in accordance with previous data showing that socioeconomic problems are major risk factors for asthma-related deaths [24]. One explanation is that government revenue, education and medical expenditures of Jilin Province are relatively low in China [6]. Furthermore, a low household income and low educational level were shown to not only decrease the adherence of asthma medication but also independently increase the risk of severe asthma exacerbations in the present study. Similarly, it has been shown that the risk of severe life threatening asthma (SLTA) increases with the lack of formal income [25]. This indicated that higher household income, increased education and medical expenditures, and higher reimbursement from insurance might aid in prevention of severe asthma exacerbations and contribute to asthma control improvement.

Atopic status and infection are both important factors for acute attack of asthma. We found 36.67 % of patients had atopic status in our study, but atopic status of patients was not risk factor for severe asthma exacerbations in the follow-up period. The comorbidity of pneumonia, which reflected partly infection in lung, was not associated with severe asthma exacerbations in the follow-up period.

Smoking has been reported to be a risk factor for poorly controlled asthma and an impaired corticosteroid response [26]. In contrast, smoking was not a significant risk factor for severe asthma exacerbations in our survey, which might be due to the lower percentage (9.96 %) of asthma patients who were currently smoking compared with other studies. The percentage of former smoker was 39.78 %. This suggested that many patients might quit smoking after diagnosis of asthma. Another reason might be difference patient resources.

The study has some limitations. There may be a selection bias because the asthma patients were enrolled only from five first-class hospitals in Jilin Province. Another limitation is the high dropout rate that 889 of 1546 patients provided a complete follow-up questionnaire. Furthermore, it is difficult to evaluate the effect of season and airway infection on severe asthma exacerbation each time, because we collected the data of severe asthma exacerbations of patients in follow up visit per three months retrospectively, but not immediately when the acute exacerbations happened. And some information in detail was not complete because the hospitalization and emergency department visit of patients were not in original hospitals sometimes. Otherwise, it is difficult to evaluate the infection situation each time, due to the partly abuse of antibiotics in China. Thus, increasing the frequency of follow-up visits and establishing the network of hospitals with different grades would be solutions. Finally, follow-up studies after discharge might increase the understanding and condition of asthma control. Further large-scale studies are warranted to validate the findings of this study.

Conclusion

Collectively, this study found unsatisfactory asthma control and a high frequency of severe asthma exacerbation in Jilin Province, which were mainly due to poor adherence to asthma medication, poor asthma symptom control, low income, a low educational level and a low proportion of reimbursements from insurance companies. Our results provide basic data for improving asthma control in Jilin Province and will help physicians instruct patients on how to avoid the risk factors associated with asthma exacerbation.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Asthma control test

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- GINA:

-

Global Initiative for Asthma

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroids

- LABA:

-

Long acting beta 2 agonist

- LAMA:

-

Long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists

- NRCMI:

-

New rural cooperative medical insurance

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCDI:

-

Per capita disposable income

- PEF:

-

Peak expiratory flow

- PFM:

-

Peak flow meter

- SABA:

-

Short acting beta 2 agonist

- SLTA:

-

Severe life threatening asthma

References

Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, Gibson P, Ohta K, O'Byrne P, Pedersen SE, Pizzichini E, Sullivan SD, Wenzel SE, Zar HJ. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–78.

Lai CK, Ko FW, Bhome A, De Guia TS, Wong GW, Zainudin BM, Nang AN, Boonsawat W, Cho SH, Gunasekera KD, Hong JG, Hsu JY, Viet NN, Yunus F, Mukhopadhyay A. Relationship between asthma control status, the Asthma Control Test and urgent health-care utilization in Asia. Respirology. 2011;16:688–97.

Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, Mink DR, Valacer DJ, Weiss ST. Real-world Evaluation of Asthma Control and Treatment (REACT): findings from a national Web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1454–61.

Cazzoletti L, Marcon A, Janson C, Corsico A, Jarvis D, Pin I, Accordini S, Almar E, Bugiani M, Carolei A, Cerveri I, Duran-Tauleria E, Gislason D, Gulsvik A, Jogi R, Marinoni A, Martinez-Moratalla J, Vermeire P, de Marco R, Therapy, Health Economics Group of the European Community Respiratory Health S. Asthma control in Europe: a real-world evaluation based on an international population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1360–7.

Su N, Lin J, Chen P, Li J, Wu C, Yin K, Liu C, Chen Y, Zhou X, Yuan Y, Huang X. Evaluation of asthma control and patient’s perception of asthma. Findings and analysis of a nationwide questionnaire-based survey in China. J Asthma. 2013;50:861–70.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for asthma management and prevention. http://www.ginasthma.org. Accessed 2012 update.

Wang Y, Yang X, Li X, He X, Zhao Y. Knowledge and personal use of menopausal hormone therapy among Chinese obstetrician-gynecologists: results of a survey. Menopause. 2014;21:1190–6.

O'Byrne PM, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, Ostlund O, Peterson S, Sears MR, Jenkins C, Humbert M, Buhl R, Harrison TW, Quirce S, Bateman ED. Measuring asthma control: a comparison of three classification systems. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:269–76.

Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas AS, Hanlon J, Watson ME, Jhingran P. The minimally important difference of the Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:719–23. e711.

Miller MK, Lee JH, Miller DP, Wenzel SE, Group TS. Recent asthma exacerbations: a key predictor of future exacerbations. Respir Med. 2007;101:481–9.

Haselkorn T, Fish JE, Zeiger RS, Szefler SJ, Miller DP, Chipps BE, Simons FE, Weiss ST, Wenzel SE, Borish L, Bleecker ER, Group TS. Consistently very poorly controlled asthma, as defined by the impairment domain of the Expert Panel Report 3 guidelines, increases risk for future severe asthma exacerbations in The Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:895–902. e891-894.

Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, Ashok M, Blalock SJ, Wines RC, Coker-Schwimmer EJ, Rosen DL, Sista P, Lohr KN. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:785–95.

Raherison C, Abouelfath A, Le Gros V, Taytard A, Molimard M. Underdiagnosis of nocturnal symptoms in asthma in general practice. J Asthma. 2006;43:199–202.

Laforest L, Van Ganse E, Devouassoux G, Osman LM, Brice K, Massol J, Bauguil G, Chamba G. Asthmatic patients’ poor awareness of inadequate disease control: a pharmacy-based survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:146–52.

Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, Kuo SH, Mukhopadhyay A, Soriano JB, Trung PL, Zhong NS, Zainudin N, Zainudin BM, Asthma I. Reality in Asia-Pacific Steering C: Asthma control in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:263–8.

Bousquet J, Boulet LP, Peters MJ, Magnussen H, Quiralte J, Martinez-Aguilar NE, Carlsheimer A. Budesonide/formoterol for maintenance and relief in uncontrolled asthma vs. high-dose salmeterol/fluticasone. Respir Med. 2007;101:2437–46.

Boulet LP, Vervloet D, Magar Y, Foster JM. Adherence: the goal to control asthma. Clin Chest Med. 2012;33:405–17.

Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, Cinti C, Lodi M, Martucci P, Serra M, Scichilone N, Sestini P, Aliani M, Neri M. Gruppo Educazionale Associazione Italiana Pneumologi O: Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105:930–8.

Ernst P, Spitzer WO, Suissa S, Cockcroft D, Habbick B, Horwitz RI, Boivin JF, McNutt M, Buist AS. Risk of fatal and near-fatal asthma in relation to inhaled corticosteroid use. JAMA. 1992;268:3462–4.

Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, Kuntz KM, Neumann PJ, Dockery DW, Weiss ST. FEV(1) is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:61–7.

Osborne ML, Pedula KL, O'Hollaren M, Ettinger KM, Stibolt T, Buist AS, Vollmer WM. Assessing future need for acute care in adult asthmatics: the Profile of Asthma Risk Study: a prospective health maintenance organization-based study. Chest. 2007;132:1151–61.

Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, Ashok M, Blalock SJ, Wines RC, Coker-Schwimmer EJ, Rosen DL, Sista P, Lohr KN. Interventions to Improve Adherence to Self-administered Medications for Chronic Diseases in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:785–95.

Barnes PJ. Theophylline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:901–6.

Sturdy PM, Victor CR, Anderson HR, Bland JM, Butland BK, Harrison BD, Peckitt C, Taylor JC. Mortality, Severe Morbidity Working Group of the National Asthma Task F: Psychological, social and health behaviour risk factors for deaths certified as asthma: a national case–control study. Thorax. 2002;57:1034–9.

van der Merwe L, de Klerk A, Kidd M, Bardin PG, van Schalkwyk EM. Case–control study of severe life threatening asthma (SLTA) in a developing community. Thorax. 2006;61:756–60.

Allegra L, Cremonesi G, Girbino G, Ingrassia E, Marsico S, Nicolini G, Terzano C, Group PS. Real-life prospective study on asthma control in Italy: cross-sectional phase results. Respir Med. 2012;106:205–14.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nr: 81300014) and Norman Bethune Medical Scientific Research Fundation-Youth Foundation (Nr:2013206039).

Availability of data and materials

Due to the privacy policy of patients, we can’t openly release the dataset of questionnaire survey underlying the conclusions of the paper available in public. A truncated dataset after eliminating all potentially identifiable features may be provided on an individual request basis.

Authors’ contributions

JL conceived and designed the research. BDY, SSM, JR wrote and edited the manuscript. BDY, SSM, JR, ZL, QHZ, JYY, RG, CMS, CFW, CLL, JZ, ZSM, JL make data collection and analyzation. ZL, QHZ, JYY, RG, CMS, CFW, CLL collected the literature. JZ, ZSM, JL, reviewed and revised it critically for important intellectual content. JL gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Hospital of Jilin University. Each patient gave their written informed consent before the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Bing-di Yan and Shan-shan Meng share first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Bd., Meng, Ss., Ren, J. et al. Asthma control and severe exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe asthma in Jilin Province, China: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. BMC Pulm Med 16, 130 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0292-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0292-3