Abstract

Background

Despite measures to reduce young people’s access to electronic cigarettes (ECs), or “vapes”, many countries have recorded rising youth vaping prevalence. We summarised studies documenting how underage youth in countries with minimum age sales restrictions (or where sales are banned) report accessing ECs, and outline research and policy implications.

Methods

We undertook a focused literature search across multiple databases to identify relevant English-language studies reporting on primary research (quantitative and qualitative) and EC access sources among underage youth.

Results

Social sourcing was the most prevalent EC access route, relative to commercial or other avenues; however, social sourcing dynamics (i.e., who is involved in supplying product and why) remain poorly understood, especially with regard to proxy purchasing. While less prevalent, in-person retail purchasing (mainly from vape shops) persists among this age group, and appears far more common than online purchasing.

Conclusions

Further research examining how social supply routes operate, including interaction and power dynamics, is crucial to reducing youth vaping. Given widespread access via schools and during social activities and events, exploring how supply routes operate and evolve in these settings should be prioritized. Inadequate compliance with existing sales regulations suggest greater national and local policy enforcement, including fines and licence confiscation for selling to minors, is required at the retailer level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Early electronic cigarettes (ECs) simulated combustible cigarettes in appearance, but second and third generation devices became more powerful and more bespoke [1]. Fourth generation ‘pods’ and disposable devices differ from earlier models in their use of nicotine salts, a more palatable e-liquid that delivers higher nicotine concentrations without the harshness typical of freebase nicotine [2, 3]. EC marketing to youth has evolved rapidly across multiple media [4, 5], with a combination of aesthetically appealing, easily hidden, and powerfully addictive devices contributing to rising EC use among young people [6, 7].

While views on ECs’ role in supporting smoking cessation vary [8,9,10], most researchers agree that young people who do not smoke face possible harm if they begin using ECs [11]. Physical harms include respiratory risks and the as yet unknown impact of sustained EC use; psychological risks include the burden dependence imposes, which may lead to anxiety, shame, and financial stress [12, 13]. Further, although causal links are disputed [14, 15], researchers have found associations between EC use and subsequent smoking [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], leading some to conclude that youth who use ECs are three times more likely to begin using smoked tobacco products than those who do not use vaping products [16, 17].

Policy makers in some countries have attempted to support movement to ECs among people who smoke and cannot quit, while preventing uptake among young people who have never smoked [22,23,24,25]. Canada, England, and Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) have set a minimum legal sales age of 18 years [26], while Tobacco 21 legislation in the US increased the minimum legal sales age in that country to 21 [27, 28]. Australia has banned consumer sales of nicotine-containing ECs and requires people to obtain prescriptions before they may legally access these products [29, 30]. Many countries require on-pack warnings and have prohibited promotions using traditional advertising media [29], and some have limited access to or banned the fruit and confectionary options popular among young people [29].

Yet, despite these policy initiatives, EC use among youth has continued to rise in Canada, the UK, Australia, NZ and elsewhere [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. While the 2019–20 National Youth Tobacco Survey suggested EC use had declined among US youth during that period, overall prevalence remained high and trends toward declining use are not yet established [38].

Efforts to reduce ECs’ appeal and availability to young people have thus not proved successful and evidence underage youth access ECs raises important questions about the supply routes they use. We therefore undertook a scoping review with two objectives: to summarise evidence of how underage youth from countries with established minimum age sales restrictions or bans report accessing ECs, and to analyse how that knowledge could inform future research and policy [39]. We compiled and synthesised data on supply sources, including social (via friends, family or other contacts), commercial (retail self-purchasing, whether in-person or online), and other (more obscure or undefined) access routes.

Methods

Search strategy

In September 2022 ADM and a University of Otago subject librarian conducted a search of peer reviewed literature across four databases. We restricted study language to English and dates from 2015 (the year in which US youth vaping appears to have peaked and before which age national restrictions had not yet been implemented) [40]. Additional File 1 outlines the search strategy, including limits and search terms applied within each database.

Study selection

ADM and JAH screened titles independently, (n = 1,870) then met to reach consensus and develop an agreed list for further review. ADM and JD then screened abstracts independently (n = 215), meeting to reach consensus. JAH further reviewed the agreed list. We included studies if they reported on primary research and EC access routes among those < 18 years of age (or those < 19 or < 21 years of age, depending on minimum age sales laws in the country of interest). We excluded studies that focused exclusively on: access to other tobacco products or cannabis; knowledge, attitudes, prevalence, or correlates of EC use; advertising or marketing; biomedical findings, or health outcomes. We also excluded studies conducted prior to implementation of EC minimum age sales laws. Additional File 1 presents inclusion and exclusion criteria, and details of study numbers at each screening phase. Additional File 2 provides an overview of these laws across the four countries represented in this review.

Data extraction and synthesis

ADM created a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to facilitate extraction of descriptive data (variables included study citation, setting, study type, objectives, methods, eligibility criteria, participant demographics, data collection dates, EC access parameters reported, ethical considerations, conflicts of interest, and funding sources). We used this spreadsheet to summarise study characteristics and identify methodological similarities and differences within included studies. ADM and JD extracted and tabulated quantitative data from surveys into a separate spreadsheet, detailing the number (and proportion) of respondents who reported access via various sources. Given variability in response categories across included surveys, ADM and JD identified matching EC access route descriptors to facilitate data synthesis.

Results

Overview of included studies

We included 17 studies in this scoping review; Fig. 1 presents the search flowchart from record identification to full-text assessment. Additional File 3 outlines characteristics and variables from included studies.

Most included studies (n = 14) were conducted in the United States (US) [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]; one was conducted in Canada [55]; one in Australia [34], and one was international (US, Canada, England) [56]. All were published in peer-reviewed journal articles; most (n = 14) were surveys and half of these reported data from a nationally representative sample [43,44,45,46,47, 50, 55]. Two studies reported on focus-groups [52, 54] and one on in-depth interviews [53]. The median start date for data collection was 2017 [34, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

For analyses relevant to underage EC access, most surveys (n = 11) included data from more than 1,000 participants [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 55, 56]; across all surveys (n = 14), the mean number of participants was 2,198 (range = 7,979) [34, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 55, 56]. Focus-group and interview-based studies included between 29 and 61 participants [52,53,54]. Sample members identified as male or female and typically ranged from age 13 to 18 years (n = 8).

Most studies (n = 12) included participants classified as ‘current’ or ‘past 30-day’ EC users (all current users had vaped in the past 30 days) [42,43,44,45,46,47, 50,51,52,53, 55, 56], though fewer (n = 5) included underage ever-users [34, 41, 48, 49, 54]. A single study reported receiving industry funding (from JUUL Labs, Inc.; the study explored access to JUUL EC products only) [44].

EC access modes: social, commercial, other

Most included surveys (n = 11) found social sources were the most prevalent means underage youth used to access ECs, relative to commercial or other (mainly undefined) sources [34, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47, 49, 50, 55, 56]. A single survey found commercial sourcing was most prevalent [48].

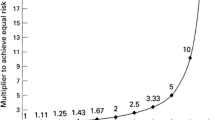

Heterogeneity in question framing within included studies affected how we present our findings. Eight surveys allowed a single response to questions examining EC access source (i.e., prevalence totalled 100%), thus allowing us to match and combine responses categories into three access modes: ‘social’, ‘commercial’, and ‘other/ unspecified’ [34, 41, 43, 46, 47, 49, 51, 55]. Two surveys provided data regarding exclusive sourcing from ‘social’ vs ‘commercial’ vs ‘both’ avenues [44, 56]. Figure 2 presents these 10 studies.

Prevalence of Key EC Access Modes Among Ever- and Current Users. a Study provided data re. exclusive sourcing from commercial vs other/unspecified avenues among current EC users (i.e., as a proportion of 100%), thus allowing for graphical presentation along with studies that allowed a single response option to questions re. EC access source. NB: First or most recent source among EC ever-users was reported in three studies, while main source among current EC users reported in seven; the two study groupings are separated by an additional space within the figure. NB: Response categories contained within ‘social’ sourcing include: friend, family, neighbour, or another contact (not a friend or relative) who either shared with, lent to, gave, or sold to the person, or bought on their behalf; response sub-categories contained within ‘commercial’ sourcing include: having self-purchased in-person at a vape shop or any other type of retailer, online, or at a flea market; response sub-categories contained within ‘other/unspecified’ sourcing include: stealing or taking, or not providing specific details re. sourcing (e.g., ‘some other way’ or ‘don’t remember’)

Social sourcing was most prevalent in eight of 10 studies, ranging from 43%-85% (weighted mean = 75%) [34, 41, 44, 46, 47, 49, 55, 56]. In five of these eight studies, social was followed by commercial sourcing, ranging from 14%-41% (weighted mean = 30%) [34, 41, 44, 46, 56]; in three, social was followed by other/unspecified sourcing, ranging from 10%-16% (weighted mean = 15%) [47, 49, 55]. Two studies did not describe access outside commercial purchasing [43, 51], thus we could only assess commercial vs other/unspecified sources (21% vs 79% and 42% vs 58%, respectively).

Among the six surveys allowing respondents to cite multiple sources, four did not provide additional data on exclusive sourcing (i.e., graphical presentation as in Fig. 2 was not feasible). Surveys reporting on main sources among current EC users found a social source was the single most prevalent response category, ranging from 43%-59% (weighted mean = 50%) [42, 44, 45, 50, 56]. One survey reporting on main sources among EC ever-users found a commercial source the single most prevalent category, ranging from 41%-61% across five individual EC device types probed (JUUL, pod vape, Cigalike, Box-Mod, and vape pen), while social sources were the second and third most prevalent categories across all five device types (9%-22% and 20%-28%, respectively) [48].

Social sourcing sub-analysis

Friend

All six surveys including ‘Friend’ as a category found this option was the single most prevalent source (social, commercial, or otherwise). Prevalence ranged from 52%-60% (weighted mean = 59%) across those reporting on either first or most recent source among EC ever-users [34, 41, 49], and from 47%-55% (weighted mean = 52%) across those reporting on main source among current EC users [42, 45, 50].

Five surveys did not include ‘Friend’ as a response category but included one or more of the following options: ‘someone gave’, ‘someone offered’, or ‘I asked someone to give me some’, which imply social sourcing [44, 46,47,48, 56]. A single study examined borrowing and sharing behaviour and reported on prevalence and friend-specific involvement [46]. Regardless of high device ownership levels, 73% of survey respondents reported borrowing someone else’s device in the past 30 days (nearly 1 in 5 borrowed frequently in that period); friends were the primary borrowing source (81%), followed by siblings (9.5%); less than five percent borrowed from parents/adult relatives, co-workers, or others. Sharing devices was also common, with 37% reporting they often or very often shared a device [46].

Family

Seven surveys included ‘Family’ (whether described as such, or as ‘Parent/Legal Guardian’ or ‘Sibling’) as a response option when examining EC access sources [34, 41, 42, 45, 46, 49, 50]. All seven found family was a much less prevalent source relative to friends, estimates reported from 9%-16% (weighted mean = 15%) of EC ever-users reporting on either their first or most recent source [34, 41, 49], and from 5%-28% (weighted mean = 11%) of current EC users reporting on their main source [42, 45, 46, 50].

Social purchasing

Six surveys examined social purchasing (i.e., asking someone to purchase or having purchased from someone) as a distinct source option. Response prevalence for ‘I got someone else to buy on my behalf’ ranged from 5%-23% (weighted mean = 15%) across those reporting on either main or most recent source among EC ever-users [34, 48]; and from 13%-43% (weighted mean = 24%) across those reporting on main source among current EC users [44, 46, 47, 56]. Response prevalence for ‘I bought from another person’ ranged from 9%-16% (weighted mean = 12%) across studies reporting on main source among current EC users [44, 46, 56].

While most reviewed studies provided no further detail about who made social purchases or the importance of these sources, two examined purchases from friends and reported prevalence (as a proportion of social purchases only) of 4% and 75% [34, 44]. One study found prevalence of purchases from family (as a proportion of social purchases) was one percent [44].

Social sourcing insights from focus groups and interviews

All three included qualitative studies found underage youth often obtained their first EC via their peers [52,53,54], with initial use commonly occurring with friends or siblings at home, at school, or in another public space (e.g., a park) [52, 53]. Device sharing usually occurred on school grounds [52,53,54] or in other social settings where there was little oversight [53, 54]. Older friends or siblings of legal purchase age played an important role in supplying younger underage youth [52, 54].

Commercial purchasing sub-analysis

Five surveys allowing only a single response option to questions assessing EC access source enabled us to match and combine response categories into three commercial purchase categories: ‘in-person’, ‘online’, and ‘other’. Figure 3 presents these studies. In-person retail was the most prevalent source, ranging from 52%-82% (weighted mean = 62%) [34, 41, 43, 46, 47]. In four of these five studies, in-person was followed by online sourcing, ranging from 24%-32% (weighted mean = 31%) [34, 41, 43, 46]; in one, in-person was followed by ‘other’ sourcing (18%) [47].

Prevalence of EC Commercial Purchasing Modes Among Ever- and Current Users. a Too few respondents purchased ECs online to report a proportion that would be statistically reliable. NB: Most recent source among EC ever-users was reported in two studies, and main source among current EC users was reported in three; the two study groupings are separated by an additional space within the figure. NB: Response categories contained within ‘in-person retail’ include: vape shop/store, smoke shop, tobacconist, convenience store, gas or petrol station, liquor store, drug store, mall kiosk; response categories contained within ‘online’ sourcing include: internet, website, or via a social media site; response categories contained within ‘other’ sourcing include: other location, ‘purchased, but not from retail store (e.g., market)'

Vape shop

Eight surveys included ‘vape shop’ as a response category for EC access questions. Among those reporting on either main or most recent source among EC ever-users, response prevalence ranged from 4%-45% (weighted mean = 27%) [34, 48], while those reporting on current EC users found response prevalence ranged from 4%-28% (weighted mean = 14%) [42, 44,45,46, 50, 51].

Convenience store/ gas station

Five surveys reporting on main source(s) among current EC users, included ‘gas station or convenience store’ as a response category; prevalence ranged from 6%-22% (weighted mean = 12%) [44,45,46,47, 50].

Smoke shop/ tobacconist

Six surveys included either ‘smoke shop’ or ‘tobacconist’ as a response category; among those reporting on either main or most recent source among EC ever-users, response prevalence ranged from 2%-16% (weighted mean = 6%) [34, 41, 48]. Those reporting on main source(s) among current EC users reported response prevalence ranging from 5%-18% (weighted mean = 7%) [46, 47, 51].

Online

Eleven surveys included ‘online’ as a response option; among those reporting on either main or most recent source among EC ever-users, prevalence ranged from 5%-37% (weighted mean = 28%) [34, 41, 48]. Those reporting on main source(s) among current EC users reported prevalence ranging from 3%-16% (weighted mean = 8%) [34, 42,43,44,45,46, 50, 56].

Commercial purchasing insights from focus groups and interviews

In two qualitative studies, underage self-purchasers commonly bought from in-person retailers who either did not verify their age or accepted a fake ID. One study found that larger shops or chain stores (e.g., 7-Eleven in the US) were more likely than small local shops to enforce age verification [53].

Discussion

Our scoping review summarises methodologically diverse studies that explored sources underage youth use to access ECs. Most included surveys found social sources to be the most prevalent EC access route among underage youth [34, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47, 49, 50, 55, 56], compared with commercial or other avenues. Only one survey found commercial sourcing was the most prevalent EC access source [48]. However, this study was limited to EC device owners so would not have detected borrowing and sharing practices among non-owners; it may thus have under-estimated actual social sourcing among underage youth.

Survey data showed friends were the most prevalent social source; [34, 41, 42, 45, 49, 50] only one survey reported on device sharing [46], which recent research suggests merits further investigation [34]. Though proxy purchasing constituted an important form of social sourcing [34, 44, 46,47,48, 56], most surveys did not identify the parties involved in these transactions; the dynamics involved therefore remain poorly understood. Two surveys reported on purchasing via friends [34, 44], though varying prevalence made it difficult to offer clear interpretations. Data from focus groups and interviews also highlighted friends’ roles in initial and ongoing EC use, particularly at schools [52,53,54].

Survey data on commercial sources, including in-person purchases, revealed these were a more prevalent source than online purchases [34, 41, 43, 46, 47]; with vape shops the most common location for in-person purchases [34, 42, 44,45,46, 48, 50, 51]. Focus group and interview data revealed underage youth purchase from retailers known to have lax age verification processes [52, 53].

Implications for research and policy

Existing minimum age sales laws and sales bans appear not to have adequately prevented youth from accessing ECs in several countries included in this review [34, 55, 56]. Further evaluation of US T21 legislation is required to assess whether a trend in declining prevalence is evident and to explore the impact this measure has had on social sourcing [42, 47, 51, 56, 57]. Given social sourcing commonly occurs in schools and other public spaces [52,53,54], future research should probe how supply routes evolve and operate within these settings. We support calls to explore sharing and borrowing behaviour, as well as device gifting and proxy purchases, in greater depth [42, 46, 49], Understanding interaction dynamics, and the parties and power structures involved, could inform policies to effectively disrupt social supply channels [44]. Probing factors that motivate EC experimentation and early use among underage youth (considering sex-specific differences, if and where appropriate) could support targeted preventive policies [42, 55, 57], including stronger and well-enforced marketing curbs [42, 56] flavour restrictions [42, 55, 58,59,60], and evidence-based youth prevention campaigns.

While social supply appears more prevalent than commercial supply, underage youth report using commercial routes when self-purchasing. Inadequate compliance with existing sales regulations suggest greater national and local policy enforcement, including fines and licence confiscation for selling to minors, is required [49, 51, 55, 56, 61,62,63].

To address the research gaps identified above and improve comparability between studies, we suggest developing a standardised approach, including common questions. Rigorous evaluation of policies aimed at limiting youth EC access would provide a robust basis for future policy development [41, 62]. For instance, better knowledge of how national legislation (e.g., T21 measures), flavour restrictions, and public education campaigns have contributed to decreases in EC use among US youth could identify opportunities to strengthen existing measures [50].

Strengths and limitations

We analysed data sourced from diverse studies representing around 30,000 participants, developed the first review analysing how underage youth access EC products, and offer new insights regarding EC use among underage youth.

Our scoping review has limitations as the published literature has a limited geographic scope; most studies were conducted in the US, and although Canada, England, and Australia are also represented, the findings may not generalise to other settings. The survey questions reviewed varied in their wording (e.g., probing of first, most recent, or main EC source), structure (e.g., single vs multiple responses options), and response categories (i.e., variable disaggregation of social, commercial, and other sources), making data synthesis challenging. Because included studies were cross-sectional, we could not describe access trends or source preferences over time. Finally, as circumstances surrounding EC product development and regulation continue to change rapidly [64], and because we did not critically appraise the included articles, we have exercised caution in outlining policy implications and instead identify research that could inform future policy [65].

Conclusions

Underage youth reported on in the studies we reviewed typically used social sources to access ECs. Explicating how social supply routes operate is crucial to reducing youth vaping. Widespread access to ECs at schools and social events makes examining interaction dynamics and supply route operation in these settings an urgent research priority, alongside effective sales and marketing controls.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated during this study are included in this published article; all data included in our analysis (from previously published peer-reviewed research articles) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lopez AA, Eissenberg T. Science and the evolving electronic cigarette. Prevent Med. 2015;80:101–6.

Barrington-Trimis JL, Leventhal AM. Adolescents’ use of “pod mod” e-cigarettes — urgent concerns. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1099–102.

Voos N, Goniewicz ML, Eissenberg T. What is the nicotine delivery profile of electronic cigarettes? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16(11):1193–203.

Lee J, Suttiratana SC, Sen I, Kong G. E-cigarette marketing on social media: a scoping review. Curr Addict Rep. 2023;10(1):29–37.

Struik LL, Dow-Fleisner S, Belliveau M, Thompson D, Janke R. Tactics for drawing youth to vaping: content analysis of electronic cigarette advertisements. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e18943.

Fadus MC, Smith TT, Squeglia LM. The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;1(201):85–93.

Lee SJ, Rees VW, Yossefy N, Emmons KM, Tan ASL. Youth and young adult use of pod-based electronic cigarettes from 2015 to 2019: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(7):714–20.

Dai H, Leventhal AM. Association of electronic cigarette vaping and subsequent smoking relapse among former smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;1(199):10–7.

Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):230–46.

Livingstone-Banks J, Lindson N, Hartmann-Boyce J, Aveyard P. Effects of interventions to combat tobacco addiction: cochrane update of 2019 and 2020 reviews. Addiction. 2022;117(6):1573–88.

Fenton E, Robertson L, Hoek J. Ethics and ENDS. Tobacco Control. 2022; https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057078.

Hamberger ES, Halpern-Felsher B. Vaping in adolescents: epidemiology and respiratory harm. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(3):378–83.

Becker TD, Arnold MK, Ro V, Martin L, Rice TR. Systematic review of electronic cigarette use (Vaping) and mental health comorbidity among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(3):415–25.

Beard E, Brown J, Shahab L. Association of quarterly prevalence of e-cigarette use with ever regular smoking among young adults in England: a time-series analysis between 2007 and 2018. Addiction. 2022;117(8):2283–93.

Levy DT, Warner KE, Cummings KM, Hammond D, Kuo C, Fong GT, et al. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: a reality check. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):629–35.

Pierce JP, Chen R, Leas EC, White MM, Kealey S, Stone MD, et al. Use of E-cigarettes and other tobacco products and progression to daily cigarette smoking. Pediatrics. 2021;147(2):e2020025122.

Hair EC, Kreslake JM, Rath JM, Pitzer L, Bennett M, Vallone D. Early evidence of the associations between an anti-e-cigarette mass media campaign and e-cigarette knowledge and attitudes: results from a cross-sectional study of youth and young adults. Tob Control. 2021.

Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Gibson LA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788–97.

Best C, Haseen F, Currie D, Ozakinci G, MacKintosh AM, Stead M, et al. Relationship between trying an electronic cigarette and subsequent cigarette experimentation in Scottish adolescents: a cohort study. Tobacco Control. 2018;27:373–8.

Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, Unger JB, Sussman S, Riggs NR, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–7.

Hammond D, Reid JL, Cole AG, Leatherdale ST. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation among youth: a longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ. 2017;189(43):E1328–36.

Balfour DJK, Benowitz NL, Colby SM, Hatsukami DK, Lando HA, Leischow SJ, et al. Balancing consideration of the risks and benefits of E-cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(9):1661–72.

Sindelar JL. Regulating vaping — policies, possibilities, and perils. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e54.

Miller TJ. The harm-reduction quandary of reducing adult smoking while dissuading youth initiation. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):788–9.

Hoek J, Freeman B. BAT(NZ) draws on cigarette marketing tactics to launch Vype in New Zealand. Tob Control. 2019;28(e2):e162–3.

Health Canada. Vaping product regulations. 2023. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/vaping/product-safety-regulation.html.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). How FDA is Regulating E-Cigarettes. FDA; 2022. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/how-fda-regulating-e-cigarettes. [Cited 2022 Dec 12].

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Newly Signed Legislation Raises Federal Minimum Age of Sale of Tobacco Products to 21. FDA; 2022. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/ctp-newsroom/newly-signed-legislation-raises-federal-minimum-age-sale-tobacco-products-21. [Cited 2022 Dec 12].

Klein DE, Chaiton M, Kundu A, Schwartz R. A literature review on international e-cigarette regulatory policies. Curr Addict Rep. 2020;7(4):509–19.

Australian Government (Department of Health and Aged Care). About e-cigarettes. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2021. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/smoking-and-tobacco/about-smoking-and-tobacco/about-e-cigarettes. [Cited 2022 Dec 12].

Hammond D, Rynard VL, Reid JL. Changes in prevalence of vaping among youths in the United States, Canada, and England from 2017 to 2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(8):797–800.

Ministry of Health NZ. Annual Update of Key Results 2021/22: New Zealand Health Survey. Ministry of Health NZ. 2022. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2021-22-new-zealand-health-survey. [Cited 2022 Dec 12].

UK Government, Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Nicotine vaping in England: 2022 evidence update summary. 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nicotine-vaping-in-england-2022-evidence-update/nicotine-vaping-in-england-2022-evidence-update-summary.

Watts C, Egger S, Dessaix A, Brooks A, Jenkinson E, Grogan P, et al. Vaping product access and use among 14–17-year-olds in New South Wales: a cross-sectional study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health.;n/a(n/a). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1753-6405.13316. [Cited 2022 Oct 27].

Connolly, H. Commissioner for Children and Young People, South Australia. Vaping Survey Key Findings: What do young people in South Australia think about current responses to vaping and how to better respond?. 2022. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ccyp.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Screen-Vaping-Survey-Key-Findings-Report.pdf. [Cited 2022 Dec 12].

Alcohol and Drug Foundation (ADF). Vaping in Australia: Key Statistics. 2022. Available from: https://adf.org.au/talking-about-drugs/vaping/vaping-youth/vaping-australia/.

Kim J, Lee S, Chun J. An international systematic review of prevalence, risk, and protective factors associated with young people’s E-cigarette use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11570.

Choi BM, Abraham I. The decline in e-cigarette use among youth in the united states—an encouraging trend but an ongoing public health challenge. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112464.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Jones K, Salzman GA. The Vaping Epidemic in Adolescents. Mo Med. 2020;117(1):56–8.

Meyers MJ, Delucchi K, Halpern-Felsher B. Access to Tobacco Among California high school students: the role of family members, peers, and retail venues. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(3):385–8.

Baker HM, Kowitt SD, Meernik C, Heck C, Martin J, Goldstein AO, et al. Youth source of acquisition for E-Cigarettes. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2019;16. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85074525092&doi=10.1016%2fj.pmedr.2019.101011&partnerID=40&md5=f19f8af39a1b47b9db4f1a8cecefbfd5.

Mantey DS, Barroso CS, Kelder BT, Kelder SH. Retail access to E-cigarettes and frequency of E-cigarette use in high school students. Tobacco Reg Sci. 2019;5(3):280–90.

McKeganey N, Russell C, Katsampouris E, Haseen F. Sources of youth access to JUUL vaping products in the United States. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2019;10. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85075358905&doi=10.1016%2fj.abrep.2019.100232&partnerID=40&md5=484f2b5340387c2a3c4eab2c274351f1.

Merianos AL, Jandarov RA, Klein JD, Mahabee-Gittens EM. Characteristics of daily e-cigarette use and acquisition means among a national sample of adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(8):1115–22.

Pepper JK, Coats EM, Nonnemaker JM, Loomis BR. How do adolescents get their e-cigarettes and other electronic vaping devices? Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(3):420–9.

Tanski S, Emond J, Stanton C, Kirchner T, Choi K, Yang L, et al. Youth Access to Tobacco products in the united states: findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of Tobacco and health study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(12):1695–9.

Cwalina SN, Braymiller JL, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, McConnell R, Barrington-Trimis JL. Prevalence of young adult vaping, substance vaped, and purchase location across five categories of vaping devices. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(5):829–35.

Groom AL, Vu THT, Landry RL, Kesh A, Hart JL, Walker KL, et al. The influence of friends on teen vaping: A mixed-methods approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(13). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85108453541&doi=10.3390%2fijerph18136784&partnerID=40&md5=7bc1384af948b0e6e50e8639ef7958b3.

Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Neff LJ, Glidden EV, Jamal A, Park-Lee E, et al. Characteristics of e-cigarette use behaviors among US youth, 2020. JAMA Network Open. 2021; Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85107841033&doi=10.1001%2fjamanetworkopen.2021.11336&partnerID=40&md5=c37f0a661e8070325407bb2ef75d6f30.

Schiff S, Liu F, Cruz TB, Unger JB, Cwalina S, Leventhal A, et al. E-cigarette and cigarette purchasing among young adults before and after implementation of California’s tobacco 21 policy. Tob Control. 2021;30(2):206–11.

Alexander JP, Williams P, Lee YO. Youth who use e-cigarettes regularly: a qualitative study of behavior, attitudes, and familial norms. Prevent Med Rep. 2019;1(13):93–7.

Schiff SJ, Kechter A, Simpson KA, Ceasar RC, Braymiller JL, Barrington-Trimis JL. Accessing vaping products when underage: a qualitative study of young adults in Southern California. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(5):836–41.

Wagoner KG, King JL, Alexander A, Tripp HL, Sutfin EL. Adolescent use and perceptions of juul and other pod-style e-cigarettes: A qualitative study to inform prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(9). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85104993548&doi=10.3390%2fijerph18094843&partnerID=40&md5=f46de81b1d538b653e46f2cd0cbbd49f.

Nguyen HV. Association of Canada’s Provincial Bans on Electronic Cigarette Sales to Minors with Electronic Cigarette Use among Youths. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020;174(1). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85074459504&doi=10.1001%2fjamapediatrics.2019.3912&partnerID=40&md5=94d35aee6d4dee5aa9f576498b12ff95.

Braak D, Michael Cummings K, Nahhas GJ, Reid JL, Hammond D. How are adolescents getting their vaping products? Findings from the international tobacco control (ITC) youth tobacco and vaping survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2020;105. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85079276695&doi=10.1016%2fj.addbeh.2020.106345&partnerID=40&md5=cbfeda5b6278a3b656e85b5dcf02a9c7.

Han G, Son H. A systematic review of socio-ecological factors influencing current e-cigarette use among adolescents and young adults. Addict Behav. 2022;1(135):107425.

Camenga DR, Fiellin LE, Pendergrass T, Miller E, Pentz MA, Hieftje K. Adolescents’ perceptions of flavored tobacco products, including E-cigarettes: a qualitative study to inform FDA tobacco education efforts through videogames. Addict Behav. 2018;82:189–94.

Harrell MB, Loukas A, Jackson CD, Marti CN, Perry CL. Flavored Tobacco product use among youth and young adults: what if flavors didn’t exist? Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):168–73.

Huang LL, Baker HM, Meernik C, Ranney LM, Richardson A, Goldstein AO. Impact of non-menthol flavours in tobacco products on perceptions and use among youth, young adults and adults: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2017;26(6):709–19.

Blackman KCA, Smiley SL, Kintz NM, Rodriguez YL, Bluthenthal RN, Chou CP, et al. Retailers’ perceptions of FDA Tobacco regulation authority. Tob Regul Sci. 2019;5(3):291–300.

O’Connell M, Kephart L. Local and state policy action taken in the United States to address the emergence of e-cigarettes and vaping: a scoping review of literature. Health Promot Pract. 2022;23(1):51–63.

Pettigrew S, Miller M, Alvin Santos J, Raj TS, Brown K, Jones A. E-cigarette attitudes and use in a sample of Australians aged 15–30 years. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2023;26:100035.

Ling PM, Kim M, Egbe CO, Patanavanich R, Pinho M, Hendlin Y. Moving targets: how the rapidly changing tobacco and nicotine landscape creates advertising and promotion policy challenges. Tob Control. 2022;31(2):222–8.

Travis N, Levy DT, McDaniel PA, Henriksen L. Tobacco retail availability and cigarette and e-cigarette use among youth and adults: a scoping review. Tobacco Control. 2021 Jul 22; Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2021/07/22/tobaccocontrol-2020-056376. [Cited 2022 Aug 14].

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the excellent support provided by Dr Richard German, Library Divisional Manager, Sciences and Health Sciences at the University of Otago.

Funding

The research was funded by a programme grant awarded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (19/641); the funding body was not involved in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ADM and JH made substantial contributions to project administration and conceptualization; ADM and JD made substantial contributions to data curation and visualization; ADM, JH, and JD made substantial contributions to the development of methods, interpretation of data, and writing and review of the MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (as all data were publicly available, ethical review was not required to undertake this research).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Detailed search strategy, screening stages, and discard reasoning.

Additional file 2.

Minimum age sales restrictions by Country and region of interest.

Additional file 3.

Detailed characteristics of included studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Graham-DeMello, A., Hoek, J. & Drew, J. How do underage youth access e-cigarettes in settings with minimum age sales restriction laws? A scoping review. BMC Public Health 23, 1809 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16755-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16755-9