Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to explore the relationship between family communication, family violence, problematic internet use, anxiety, and depression and validate their potential mediating role.

Methods

The study population consisted of Chinese adolescents aged 12 to 18 years, and a cross-sectional survey was conducted in 2022. Structural equation models were constructed using AMOS 25.0 software to examine the factors that influence adolescent anxiety and depression and the mediating effects of problematic internet use and family violence.

Results

The results indicate that family communication was significantly and negatively related to family violence (β = -.494, p < 0.001), problematic internet use (β = -.056, p < .05), depression (β = -.076, p < .01), and anxiety (β = -.071, p < .05). And the finds also indicate that family violence mediated the relationships between family communication and depression (β = -.143, CI: -.198 -.080), and between family communication and anxiety (β = -.141; CI: -.198 -.074). Chain indirect effects between family communication and depression (β = -.051; CI: -.081 -.030) or anxiety (β = -.046; CI: -.080 -.043) via family violence and then through problematic internet use were also found in the present study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, positive family communication is crucial in reducing anxiety and depression in adolescents. Moreover, problematic internet use and family violence mediate the effects of positive family communication on anxiety and depression. Therefore, improving family communication and promoting interventions aimed at reducing family violence and problematic internet use can help reduce anxiety and depression in adolescents, thus promoting their healthy development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence is considered a crucial phase of individual development and transition, encompassing physiological, psychosocial, and cognitive transformations that often manifest as various psychological disorders [1]. Among these mental health issues, anxiety and depression have emerged as the most prevalent afflictions affecting adolescents [2]. Anxiety is frequently characterized by an excessive response to challenging or unpredictable situations, including obsessive–compulsive tendencies, worry, tension, and panic [3]. Conversely, depression represents a condition of persistent and pronounced sadness [4]. These two psychological disorders tend to exhibit similar traits and frequently co-occur, with approximately 85% of individuals with depression also experiencing significant anxiety symptoms, and 90% of those with anxiety disorders simultaneously presenting depressive symptoms [5]. Studies have revealed that globally, around 34% of adolescents aged 10–19 years are at risk of clinical depression, with a particularly elevated risk among Asian adolescents [6]. Another study, encompassing adolescent populations in 82 countries, indicated a global overall prevalence of anxiety among adolescents to be 9%. The persistence of depressive and anxious symptoms in adolescents can profoundly disrupt their developmental process and lead to considerable detriment in their social relationships and physical well-being [7]. Notably, during the Covid-19 pandemic, a quarter of adolescents worldwide experienced heightened depressive symptoms, while one-fifth grappled with significantly deeper anxiety symptoms. The pandemic exacerbated anxiety and depression in adolescents compared to previous reports from large-scale adolescent cohorts [8]. A meta-analysis conducted in China demonstrated that the Covid-19 pandemic notably impacted the mental health of over one-fifth of middle and high school students, revealing a higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to studies not involving Covid-19 [9]. However, it is important to note that the prevalence of anxiety and depression varies significantly across countries. As a result, researchers have encouraged the adoption of socio-culturally specific strategies and tools, such as focusing on family relationships, to effectively prevent anxiety and depression problems [6].

The family, functioning as an ecosystem, assumes a highly significant role in the development of adolescent mental health by acting as a protective buffer against adverse mental health problems and reducing the risk of such issues arising [10]. From a sociological standpoint, family functioning profoundly influences the physical and mental well-being of individuals. Families that exhibit healthier functioning tend to offer greater emotional and material support to their members, assisting them in coping more effectively with negative conflicts [11]. Olson's Circumplex model of marital and family systems highlight family communication as the primary facilitating dimension for enhancing family cohesion and flexibility, both of which contribute significantly to the psychological well-being of family members [12]. Family communication, defined as the exchange of information, ideas, thoughts, and emotions among family members [13], serves as a pivotal bridge in transmitting emotions within the family and significantly influences the development of adolescent mental health [14]. Positive family communication is characterized by the ability of family members to comprehend, trust, and attentively listen to one another, while negative family communication typically involves an inability to engage in calm dialogues and express emotions and ideas effectively. León-Del-Barco and his colleagues underscored the pivotal role of the family environment in adolescent development, emphasizing that communication styles and behavioral patterns within the family exert a profound impact on adolescent mental health [15]. Moreover, family systems theory posits that problems among family members can often be traced back to miscommunication within the family unit [16]. Negative family communication, such as family conflict and reduced frequency of communication, can erode family relationships, lead to unhealthy family behaviors, and contribute to adolescent anxiety and depression [17]. Conversely, studies have demonstrated that positive parent-adolescent communication fosters a stronger bond between adolescents and their parents, promoting family cohesion and resilience, which serves as a crucial protective factor against adolescent depression [18]. Despite Geçer and Yıldırım's empirical study suggesting a direct impact of family communication in adults on psychological distress in the context of Covid-19 [19], very few studies have specifically investigated the influence of family communication on adolescents' psychological problems of anxiety and depression. Furthermore, there is a dearth of research exploring the mechanistic relationship between family communication and psychological disorders. In light of the Covid-19 impact, both parents and adolescents in China have been compelled to curtail their activities outside the home, resulting in prolonged close interactions with their family members [20]. In this context, the significance of family communication becomes even more prominent, and its impact on adolescents' mental well-being assumes greater importance. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the relationship between family communication and adolescents' anxiety and depression in the context of Covid-19, as well as the mechanisms that influence this relationship.

Adolescents exposed to family violence are at an increased risk of experiencing depression and anxiety. Family violence refers to the mental and physical abuse endured by an individual from other family members [21, 22]. Research has demonstrated that adolescents living in environments with parental family violence are more susceptible to depression compared to those not exposed to such family violence [23]. Furthermore, exposure to family violence not only heightens the likelihood of depression in adolescents but also leads to adverse physiological responses, such as elevated blood pressure, as a consequence of the depression [24]. Prolonged exposure to family violence during childhood, particularly from mothers, is associated with elevated psychological problems, such as depression and anxiety, during adolescence [25]. According to the Global Status Report on Violence Against Children 2020, jointly published by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund, approximately one in two children between the ages of 2 and 17 years worldwide experiences some form of violence each year. Nearly 300 million children between the ages of 2 and 4 years are regularly subjected to violent discipline by their caregivers [26]. While authoritative statistics on family violence against adolescents in China are not available, data from reputable Chinese media indicates that almost 45% of parents have resorted to family violence against their children, primarily in the form of verbal abuse, and on average, a child experiences family violence once a month [27]. These statistics underscore the frequency of adolescents' exposure to family violence. The Behavioral Family Systems Model posits that communication skills play a vital role in family functioning, reducing family conflict, promoting positive family relationships, and enhancing adolescents' resilience in coping with stress [28]. Olson's Circumplex model of marital and family systems has consistently revealed that family communication fosters family cohesion and resilience, as supported by a wealth of empirical studies [29,30,31]. Furthermore, high levels of family cohesion and resilience have been associated with decreased exposure to family abuse [32]. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that family communication acts as a protective factor for adolescents against family violence and, consequently, alleviates psychological problems such as anxiety and depression. Especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, when family members have had more frequent interactions, the potential for the occurrence of family violence has increased [33], subsequently elevating the likelihood of adolescents experiencing anxiety and depression [34]. More explicitly, we can hypothesize that family communication's mitigating effect on anxiety and depression in adolescents is achieved through its role in reducing family violence.

Problematic Internet use emerges as a significant contributing factor to the heightened risk of depression and anxiety in adolescents. This issue shares behavioral characteristics akin to drug addiction, alcoholism, and gambling addiction, and exerts adverse effects on an individual's social relationships, as well as their physical and mental well-being [35]. Numerous studies have substantiated the association between problematic Internet use and adverse mental health outcomes. For instance, a cross-sectional study by Li et al. demonstrated a direct increase in the risk of depression among Chinese middle school students due to problematic Internet use [36]. Adolescents exhibiting problematic Internet use displayed significantly poorer mental and emotional states compared to their counterparts without such behaviors [37]. Particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, the correlation between problematic Internet use and adolescent anxiety and depressive symptoms became evident, with related studies highlighting the direct impact of problematic Internet use on anxiety and depression [38]. The detrimental impact of problematic Internet use on adolescent mental health can be attributed to the tendency for excessive Internet engagement to reduce real-world social interactions among adolescents [39]. As they spend more time in the virtual world, they may have less interaction with their friends and family in real life. This substitution of "virtual socialization" for "real socialization" may exacerbate symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, it is noteworthy that Chinese adolescents' Internet use is often regulated by their parents, making the family a crucial influence on adolescents' problematic Internet use. Nielsen, Favez, and Rigter's literature review on parenting, family factors, and adolescents' problematic Internet use highlighted that positive family parenting and family dynamics were associated with lower problematic Internet use, while negative parenting and family dynamics were linked to higher rates of problematic Internet use [40]. When parents maintain a positive communication relationship with their children, such as actively listening and understanding their thoughts, it typically reduces adolescents' problematic Internet use [41]. Similarly, positive family environments, such as increased family expression, have been shown to reduce adolescents' problematic Internet use and time spent online [42]. Family systems theory posits that individual and family members' behaviors are influenced by the patterns of family relationships, which can have an intergenerational transfer effect [43]. For instance, individuals in families with healthier communication patterns are more likely to develop healthy interpersonal relationship patterns in the future. Conversely, unhealthy communication within the family may lead to problematic interpersonal relationships or even conflict and violence in the future. In summary, we propose that adolescents' problematic Internet use likely serves as a mediator of the effect of family communication on their anxiety and depression. Positive family communication can help reduce adolescents' problematic Internet use, consequently lowering their risk of anxiety and depression. Furthermore, when family communication is positive, there is a corresponding reduction in family conflict and violence, which may also play a significant role in reducing adolescents' problematic Internet use.

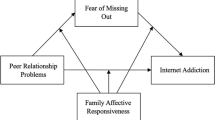

In this paper, we aim to investigate the relationship between adolescent family communication and anxiety and depression, as well as explore the potential mediating roles of family violence and problematic Internet use. We propose the following research hypotheses and present the research model diagram (see Fig. 1):

-

Hypothesis 1: Family communication is negatively associated with adolescent anxiety and depression.

-

Hypothesis 2: Family violence mediates the relationship between family communication and adolescent anxiety and depression.

-

Hypothesis 3: Problematic Internet use mediates the relationship between family communication and adolescent anxiety and depression.

-

Hypothesis 4: Family violence and problematic Internet use jointly play a chain mediating role between family communication and adolescent anxiety and depression.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The data used in this study comes from the "2022 China Population Psychological and Behavioral Survey". The survey was carried out from June 20 to August 31, 2022, in 148 cities, 202 counties, 390 towns/streets, and 780 communities/villages (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) across 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities directly under the central government in China [44]. A large number of investigators were recruited and rigorously trained nationwide for the survey. Respondents were invited to respond face-to-face and one-on-one through an electronic questionnaire. Participants will be asked to sign an informed consent form before responding. A total of 31,480 questionnaires were distributed, and 30,505 valid questionnaires were finally collected, resulting in an effective rate of 96.9%. For this study, adolescents aged 12–18 years were selected from the data, and after excluding the samples with illogical answers such as who are currently enrolled in a master's or doctoral program, a total of 2,711 valid samples were obtained. The sample screening process is shown in Fig. 2. This study has been officially registered with the China Clinical Trials Registry (Registration number: ChiCTR2200061046, 15/06/2022) and has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No.2022-K050).

Of all 2,711 samples, 1,601 (59.1%) were female, 1,742 (64.3%) were high school and below, 1,960 (72.3%) lived in urban areas, and 438 (16.2%) had a per capita monthly household income of more than 9,000.

Measures

General characteristics

The general characteristics of the participants were collected, including gender, age, residence, education level, and monthly per capita household income.

Family communication

The assessment of family communication was carried out using the Family Communication Scale (FCS) developed by Olson et al. (2011). This scale consists of 10 items designed to evaluate the quality of communication among family members from the individual's perspective, as well as the communication skills and abilities of family members. Sample items include "Family members are satisfied with the way they communicate with each other," "Family members are able to have calm discussions about issues," and "Family members receive honest responses when they ask each other questions." Participants rated their responses on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates strong disagreement and 5 represents strong agreement (Cronbach's α = 0.969; M = 36.64, SD = 8.94). A higher total score indicates a higher quality of family communication. During the data analysis phase, we randomly divided the 10 questionnaire items into 3 factors to enhance the model fit.

Family violence

To measure the violence experienced by adolescents from family members, a five-item family violence scale was developed, comprising two dimensions: mental violence and physical violence. (a) The mental violence dimension includes three items: "My family does not care about me when I am in a bad state (physically unwell or in a bad mood)." "My family invades my privacy by going through my cell phone, dictates what I wear, and restricts my interpersonal interactions." "My family compares me to others and openly accuses me, causing me embarrassment and undermining my self-confidence." (b) The physical violence dimension consists of two items: "My family has physically harmed me using direct blows or objects." "My family has engaged in unwanted physical contact with me." Participants rated their responses on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates "almost never," 2 denotes "sometimes," and 3 stands for "often" (Cronbach's α = 0.901; M = 7.70, SD = 4.04). The total score was calculated by summing the scores of the five question items, with higher scores indicating a higher level of exposure to family violence. In this study, the Cronbach's α of the Family Violence Scale was 0.901, indicating good internal consistency. Moreover, the results of the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the scale exhibited high reliability, as evidenced by the following fit indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.932, Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.931, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.910, Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.932, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.046.

Problematic internet use

This study employed the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire Short Form (PIUQ-SF-6) developed by Opakunle et al. [45] to measure problematic Internet use. The scale comprises three dimensions: obsession, neglect, and control, with a total of six question items, two for each dimension. For instance: "Have you ever experienced feelings of worry, moodiness, or tension when not online, but once you are online, these feelings disappear?" "Do you feel nervous, irritable, or stressed if you are unable to go online when you want to?" Participants provided responses to each question item using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "1 = never" to "5 = all the time" (Cronbach's α = 0.911; M = 14.23, SD = 5.62). Higher scores on the scale indicate a higher degree of problematic Internet use, suggesting a stronger association with Internet-related issues and potential negative consequences.

Anxiety

The 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) was developed by Spitzer et al. [46] and has gained widespread usage in clinical settings and various studies, particularly for screening anxiety disorders. The GAD-7 comprises seven items that assess symptoms of generalized anxiety, such as "feeling tense, anxious, or on edge" and "not being able to stop or control worrying." Participants were asked to rate how often they experienced these symptoms in the past two weeks based on their feelings. The scale was rated on a four-point scale, with responses ranging from "0 = not at all" to "3 = almost every day" (Cronbach's α = 0.954; M = 12.33, SD = 5.24). Higher scores on the scale indicate a higher level of anxiety severity. During the data analysis phase, the 7 question items of the scale were randomly divided into 3 factors to enhance the fit of the model, making it more suitable for the study's purposes.

Depression

Depression was measured using the well-established 9-item Depression Screening Scale known as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This self-rating scale is a simple yet effective tool for screening individuals for depression and is widely used internationally, with translations available in multiple languages [47, 48]. The PHQ-9 comprises nine common symptoms associated with depression, such as "feeling down, depressed, or hopeless" and "having little interest or pleasure in doing things." Participants were asked to rate how often they experienced these symptoms in the past two weeks based on their feelings. Responses were recorded on a four-point scale, with options ranging from "0 = not at all" to "3 = almost every day" (Cronbach's α = 0.928; M = 16.40, SD = 6.19). Higher scores on the scale indicate a higher level of depression severity. During the data analysis phase, the 9 question items of the scale were randomly grouped into 3 factors to enhance the model fit, making it more suitable for the study's analytical purposes.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 25.0, with two-tailed p-values at the 0.05 level considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics, such as mean, standard deviation, and sample size, were computed using SPSS 25.0. Scale reliability and validity tests, path analysis, and mediation tests were conducted using AMOS 25.0. To test the hypothesized mediation models, a structural equation model (SEM) with asymptotically distribution-free estimation was employed. The analysis assessed direct, indirect, and total effects through 2,000 bootstrapped samples to ensure robustness and accuracy of the results. Effect estimates and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the variables under investigation.

Results

Scale reliability and validity tests

Reliability and convergent validity tests of scales

In this paper, all dimensions of all scales were analyzed by CFA and the results showed that all factor loadings met the criteria recommended by Joreskog and Sorbom of greater than 0.45 and significant [49]. Further, the component reliabilities were all greater than or equal to 0.7, while the mean variance extractions ranged from 0.906 to 0.968 (Table 1), which meets the discriminant criteria proposed by Fornell and Larcker [50] and Chin [51], i.e., the Composite Reliability (CR) value should be greater than 0.7, the AVE value should be no less than 0.5, and the factor loadings for each question item should be greater than 0.5. Therefore, the five scales presented high reliability and convergent validity.

Reliability and convergent validity tests of scales

In this study, the AVE method proposed by Fornell and Larcker was used to test the discriminant validity of the variables [50]. The AVE method means that the average variance extracted for each dimension must be greater than the squared value of the correlation coefficients between the dimensions and the dimensions, but since the AVE is a squared value, it must be converted into the same squared unit if it is to be compared with the Pearson correlation between the dimensions. Therefore, the AVE value is generally rooted and then compared, and if it is higher than the value of the inter-dimension Pearson correlation, the dimension can be claimed to have differential validity. In this study (Table 2), the AVE values are in bold diagonal, and all AVE values are greater than the standardized correlation coefficients under the diagonal. Therefore, we consider the validity of the distinction between the study variables to be good.

Overall model fit analysis

This study uses the model fitting criterion recommended by Hu and Bentler [52], including χ2/df < 3, Goodness of Fit ≥ 0.95, Adjust Goodness of Fit ≥ 0.95, Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) of ≥ 0.95, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI) ≥ 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of ≤ 0.08 and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) of ≤ 0.08.

First of all, since the dependent variables Depression and Anxiety have strong correlation, while their relationships and difference are not the focus of this study. Therefore, we established a correlation between them in the model fitting stage in order to improve the overall model fitting effect. Secondly, when the sample size is larger than 1,000 and does not conform to a positive-trait distribution, Browne's recommendation of asymptotically distribution-free model estimation can be used [53]. Thirdly, since the sample size of this study reaches 2711, the model chi-square value will result in a significant p-value due to the large sample size and make the sample fit poorly to the model matrix. Therefore, we used the bootstraps method proposed by Bollen and Stine to correct the model fit indicators [54]. The chi-square value obtained after the Bollen-Stine P correction analysis was 184.62, while the original model had a chi-square value of 754.53, so all other fitness metrics needed to be recalculated. Then, the calculated fitness metrics show that the model of this study has a good fit, indicating that the model of adolescent family communication and mental health constructed by the sample of this study can be used to explain the actual observed data, and the fit results are presented in Table 3.

Path testing for structural equation model

Regarding the path analysis for the structural equation model, family communication was significantly and negatively related to family violence (β = -0.494, p < 0.001), problematic internet use (β = -0.056, p < 0.05), depression (β = -0.076, p < 0.01), and anxiety (β = -0.071, p < 0.05) with moderate or small effect sizes. In contrast, family violence exhibited significant and positive relations with problematic internet use (β = 0.397, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.290, p < 0.001), and anxiety (β = 0.285, p < 0.001) with moderate or small effect sizes. Furthermore, problematic internet use was significantly and positively related to depression (β = 0.302, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 0.310, p < 0.001) with moderate effect sizes. The results were presented in Table 4 and Fig. 3.

Mediating role analysis

Indirect effects among family communication, depression and anxiety were analyzed by performing a bootstrap with 2000 resamples and a bias-corrected and Percentile confidence interval of 95%. As is shown in Table 5, four indirect effects were significant among family communication, depression and anxiety. Family violence mediated the relationships between family communication and depression (β = -0.143, CI: -0.198 -0.080), and between family communication and anxiety (β = -0.141; CI: -0.198 -0.074). Chain indirect effects between family communication and depression (β = -0.051; CI: -0.081 -0.030) or anxiety (β = -0.046; CI: -0.080 -0.043) via family violence and then through problematic internet use were also found in the present study. Besides, the proportional values of indirect-only mediated effects of the four is 65.30%, 66.51%, 38.64%, and 42.42%. The model explained 46.21% of the participants anxiety and 33.6% of the participants depression. However, the mediating role of problematic internet use in the relationship between family communication and anxiety and depression was not significant. As a result, H4 was supported, while H3 was not.

Discussion

This study focused on anxiety and depression among Chinese adolescents during the Covid-19 context and utilized structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between family communication and adolescents' anxiety and depression. Additionally, the study explored the potential mediating roles of family violence and problematic Internet use in this context. The results of the study revealed a significant negative correlation between family communication and adolescents' anxiety and depression, indicating that positive family communication can effectively reduce adolescents' psychological distress. Moreover, family violence was found to mediate the relationship between family communication and anxiety and depression, suggesting that family violence may play a crucial role in influencing the association between family communication and adolescent mental health. Contrary to Hypothesis H3, problematic Internet use did not mediate the relationship between family communication and anxiety and depression. However, the study confirmed the presence of a common chain mediating role involving both family violence and problematic Internet use, linking them to the impact of family communication on adolescent anxiety and depression. Overall, the findings of the study support hypotheses H1, H2, and H4, and provide valuable insights into the factors influencing adolescent mental health problems. These findings have significant implications for understanding the role of family communication and violence in adolescents' mental well-being, offering useful directions for family communication and violence interventions aimed at improving the mental health of adolescents.

Positive family communication can reduce the risk of anxiety and depression in adolescents

Based on the results of this study, it was found that positive family communication plays a significant role in reducing the risk of anxiety and depression in adolescents. This suggests that adolescents who experience a more positive and open family communication environment are less likely to suffer from severe anxiety and depression. These findings align with a study conducted by Zhou et al. [55], which also demonstrated that adopting positive and conversation-oriented family communication can prevent adolescents' risk of depression. Bowen's family systems theory proposes that each family operates within an emotional system where emotional connections among family members are interconnected. Positive family communication involves the free flow of information, empathic understanding between parents and children, clear and accurate messaging, consistent parenting, and satisfying interactions [56]. Such positive communication fosters a sense of security, controllability, and predictability in adolescents' lives, leading to a reduction in negative emotions [57, 58]. On the other hand, unhealthy family communication, characterized by negativity and avoidance, can contribute to increased stress in adolescents' school and personal lives, thereby increasing their vulnerability to anxiety and depression [57]. It is essential to highlight the significance of family communication, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, when adolescents are exposed to vast amounts of information related to illness and risk. These changes in information processing and learning patterns can easily impact their mental health, leading to issues like anxiety and depression [59]. Family communication becomes a crucial means of coping with uncertainty during such challenging times. Active communication with parents allows adolescents to obtain accurate information about the epidemic, reducing their perception of future uncertainty and risk, and alleviating adverse emotions [60]. As a result, family interventions targeted at adolescents' anxiety and depression should prioritize improving the family communication climate. Parents should learn to listen to their children's thoughts and reduce critical and blaming attitudes. The findings of this study underscore the importance of positive family communication in promoting adolescent mental health. By promoting such communication, we can effectively reduce the risk of anxiety and depression in adolescents, especially during challenging situations like the Covid-19 pandemic. Future family interventions should focus on enhancing the family communication environment to aid adolescents in better coping with stress and emotional challenges.

Family violence mediates the relationship between family communication and anxiety and depression

Another significant research discovery pertains to the mediating role of family violence between family communication and adolescents' anxiety and depression. This suggests that fostering positive family communication may assist adolescents in avoiding victimization from family members, thereby reducing their susceptibility to anxiety and depression. Jiménez's study [57] demonstrated that family communication problems serve as a risk factor for family violence, while open communication aids in mitigating this risk. The Circumplex Model framework of family functioning proposed by Olson et al. [61] helps elucidate this relationship. Family communication plays a pivotal role in promoting family cohesion and flexibility. Families facing communication challenges are more likely to exhibit low flexibility (i.e., difficulty in adapting norms and rigidity) and low cohesion (i.e., inadequate connections among family members). In essence, positive family communication fosters greater family cohesion and flexibility, serving as a protective factor against adolescents falling prey to family violence, thus promoting their mental well-being. Positive family communication places emphasis on harmonious dialogue among family members, whereas inadequate family communication tends to be submissive and contradictory [62]. Conversation-oriented family communication typically enhances adolescents' mental health, whereas conformity-oriented family communication, conversely, exhibits a negative correlation with adolescents' mental well-being [63]. In China, family education often follows an authoritative approach, leading to a higher likelihood of adolescents becoming victims of family violence, especially from parents [64]. Authoritarian family upbringing usually involves less emotional support and more criticism and behavioral control [65], resulting in strained parent–child relationships and an increased risk of depression [66]. The context of Covid-19 has significantly increased the occurrence of family violence [67]. This is due to the elevated risk factors brought about by Covid-19, resulting in heightened uncertainty among family members and a greater propensity for conflicts. Moreover, with most family members living in close quarters due to Covid-19, parental emotions from work or daily life may be displaced onto children or adolescents. Consequently, harmonious communication, mutual understanding, and effective problem-solving within the family have been recognized as crucial clinical strategies for mitigating family conflict and violence stemming from Covid-19 [68]. These findings provide valuable insights into the influence of family communication and family violence on adolescent mental health. In practice, there should be a strong emphasis on promoting positive family communication, alongside efforts to strengthen family violence intervention and prevention measures. Particularly in the context of Covid-19, it is imperative to implement effective measures to ameliorate the adverse effects of family conflict and violence and safeguard the mental well-being of adolescents.

Family violence and problematic internet use as chain mediators between family communication and the relationship between anxiety and depression

The findings suggest that while problematic internet use does not directly act as a mediating mechanism between family communication and anxiety and depression, family violence and problematic internet use function as co-chain mediators in this relationship. This novel contribution to existing literature highlights the role of problematic internet use as a consequence of family violence, which, in turn, influences adolescent anxiety and depression. Specifically, we observed that inadequate family communication may result in mental or physical violence from family members, leading to an increase in problematic internet use among adolescents, ultimately exacerbating their mental health issues. This phenomenon can be elucidated through the lenses of self-regulation theory and approach-avoidance theory. According to self-regulation theory, individuals tend to employ specific strategies to regulate and manage their emotional and psychological states [69]. When adolescents face violence from family members, they may lack healthy and positive emotion regulation strategies, such as seeking social support, expressing emotions, or actively problem-solving. Consequently, problematic internet use becomes a seemingly simple and instant escape, enabling them to temporarily alleviate their discomfort without addressing the underlying problem. Additionally, approach-avoidance theory suggests that individuals may respond in an avoidance or coping manner when confronted with stressful events. Given that the adolescent population is mentally immature and possesses limited coping skills, they may be more inclined to adopt an avoidance response [70]. In the context of Covid-19, external avoidance approaches may be less accessible to adolescents, leading them to turn to the Internet as their primary means of venting and regulating their internal emotions. Nevertheless, this escape may further intensify their negative psychological emotions [38]. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the relationship between adolescents' family relationships and mental health is complex and contradictory, necessitating further research to delve deeper into how family relationships, family violence, and problematic internet use impact adolescents' mental well-being. Particularly in the context of Covid-19, changes in family and online environments may have a more intricate influence on adolescents' mental health, calling for more in-depth exploration and understanding of this domain.

Limitations and implications

The study's limitations warrant consideration. Firstly, the cross-sectional design employed restricts the establishment of causal relationships between family communication and anxiety and depression. Future research should adopt a longitudinal design to ascertain the directionality of these associations. Secondly, the study solely focused on family communication as a family factor; to gain a more comprehensive understanding, future research should incorporate other factors like family satisfaction, parental mental health, and family socioeconomic status. Thirdly, the study exclusively included adolescents, necessitating future research to encompass a broader sample group to better comprehend the impact of family violence. Lastly, the study solely concentrated on family violence and problematic internet use as mediators, overlooking other potential mechanisms. Future research should explore additional social, school, family, and individual factors beyond the study's scope.

Despite these limitations, the study's results carry significant practical implications. It stands as one of the few inquiries delving into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between family communication, family violence, problematic internet use, anxiety, and depression. The findings underscore the significance of family communication and family violence in influencing problematic behaviors and psychological well-being among adolescents, emphasizing the necessity to enhance adolescents' communication skills with their parents and reduce the incidence of family violence. Furthermore, while previous studies have mainly investigated the effects of family relationships on perpetrators, this study fills an important gap by shedding light on the psychological and behavioral manifestations experienced by adolescent victims of family violence from their perspective.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the connections between family communication, family violence, and problematic internet use in relation to adolescent anxiety and depression, providing valuable insights into their underlying mechanisms. Particularly, positive family communication exhibits a negative association with adolescent anxiety and depression, indicating that fostering healthy family communication can mitigate negative psychological symptoms in adolescents. Furthermore, family violence acts as a mediator between family communication and anxiety and depression, underscoring the potential of improving family communication to prevent adolescents from becoming victims of family violence and indirectly reduce their vulnerability to anxiety and depression. Additionally, the study reveals a co-chain-mediated effect of family violence and problematic internet use on the relationship between family communication and anxiety and depression, suggesting that adolescents may employ problematic internet use as a coping mechanism for dealing with the negative emotions stemming from family violence. Consequently, enhancing family communication skills emerges as a significant approach to alleviate adolescents' anxiety and depression, consequently reducing the prevalence of family violence and problematic internet use.

These findings carry significant implications for families, educational institutions, and society at large. In the endeavor to help adolescents alleviate anxiety and depressive symptoms, a strong emphasis should be placed on the importance of family communication, promoting understanding and support among family members through positive communication. Concurrently, proactive measures should be taken to prevent and intervene in family violence, safeguarding the physical and mental well-being of adolescents. Moreover, attention should be given to adolescents' problematic internet use, guiding them in the proper utilization of internet resources and discouraging excessive reliance on virtual socialization, as this can contribute to a reduction in their anxiety and depression levels.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available, upon reasonable request, by emailing: bjmuwuyibo@outlook.com.

Change history

27 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17226-x

References

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & adolescent health. 2018;2(3):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1.

White SW, Simmons GL, Gotham KO, Conner CM, Smith IC, Beck KB, Mazefsky CA. Psychosocial treatments targeting anxiety and depression in adolescents and adults on the autism spectrum: review of the latest research and recommended future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(10):82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0949-0.

Julian, L. J. (2011). Measures of anxiety. Arthritis care & research, 63(0 11) https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20561

Thapar A, Eyre O, Patel V, Brent D. Depression in young people. Lancet (London, England). 2022;400(10352):617–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01012-1.

Tiller JW. Depression and anxiety. Med J Aust. 2013;199(6):S28–31.

Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):287–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12333.

Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.896.

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482.

Zhang C, Ye M, Fu Y, Yang M, Luo F, Yuan J, Tao Q. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teenagers in China. The J Adolescent Health. 2020;67(6):747–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.026.

Haefner J. An application of Bowen family systems theory. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35(11):835–41.

Hu X. Chinese fathers of children with intellectual disabilities: their perceptions of the child, family functioning, and their own needs for emotional support. Int J Develop Dis. 2022;68(2):147–55.

Olson DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. J Fam Ther. 2000;22(2):144–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144.

Olson DH, Gorall DM, Tiesel JW. Faces IV package. Minneapolis MN. 2004;39:12–3.

Guo N, Ho HCY, Wang MP, Lai AY, Luk TT, Viswanath K, Chan SS, Lam TH. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the family communication scale in the chinese population. Front Psychol. 2021;12:736514. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.736514.

León-Del-Barco B, Fajardo-Bullón F, Mendo-Lázaro S, Rasskin-Gutman I, Iglesias-Gallego D. Impact of the familiar environment in 11-14-year-old minors’ mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071314.

Rothbaum F, Rosen K, Ujiie T, Uchida N. Family systems theory, attachment theory, and culture. Fam Process. 2002;41(3):328–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41305.x.

Morelli NM, Hong K, Elzie X, Garcia J, Evans MC, Duong J, Villodas MT. Bidirectional associations between family conflict and child behavior problems in families at risk for maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2022;133:105832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105832.

Ioffe M, Pittman LD, Kochanova K, Pabis JM. Parent-adolescent communication influences on anxious and depressive symptoms in early adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49(8):1716–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01259-1.

Geçer E, Yıldırım M. Family communication and psychological distress in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: mediating role of coping. J Fam Issues. 2023;44(1):203–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211044489.

Yang Y, Liu K, Li M, Li S. Students’ affective engagement, parental involvement, and teacher support in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in China. J Res Technol Educ. 2022;54(sup1):S148–64.

Mehlhausen-Hassoen D, Winstok Z. The association between family violence in childhood and mental health in adulthood as mediated by the experience of childhood. Child Indic Res. 2019;12:1697–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9605-9.

Chen Q, Song Y, Huang Y, Li C. The interactive effects of family violence and peer support on adolescent depressive symptoms: the mediating role of cognitive vulnerabilities. J Affect Disord. 2023;323:524–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.080.

Pelcovitz D, Kaplan SJ, DeRosa RR, Mandel FS, Salzinger S. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents exposed to domestic violence and physical abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(3):360–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087668.

Lawrence T. Family violence, depressive symptoms, school bonding, and bullying perpetration: an intergenerational transmission of violence perspective. J Sch Violence. 2022;21(4):517–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2022.2114490.

Marçal KE. Intimate partner violence exposure and adolescent mental health outcomes: the mediating role of housing insecurity. J Int Viol. 2022;37(21–22):NP19310–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211043588.

Global status report on the prevention of violence against children in 2020 9789240007093-chi.pdf (who.int)

http://jingji.cctv.com/2016/02/25/ARTIMP9U6uuJsg1R5QWKtoBB160225.shtml

Foster SL, Robin AL. Parent–adolescent conflict and relationship discord. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of childhood disorders. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. p. 601–46.

Lim JW, Shon EJ. The dyadic effects of family cohesion and communication on health-related quality of life: the moderating role of sex. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(2):156–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000468.

Barnes, H. L., & Olson, D. H. (1985). Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child development, 438–447.

Kluwin TN, Gaustad MG. The role of adaptability and communication in fostering cohesion in families with deaf adolescents. Am Ann Deaf. 1994;139(3):329–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2012.0308.

Gao X, Sun F, Marsiglia FF, Dong X. Elder mistreatment among older Chinese Americans: the role of family cohesion. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2019;88(3):266–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415018773499.

Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20200982. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0982.

Thiel F, Büechl V, Rehberg F, Mojahed A, Daniels JK, Schellong J, Garthus-Niegel S. Changes in prevalence and severity of domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Front Psych. 2022;13:874183.

Walther B, Morgenstern M, Hanewinkel R. Co-occurrence of addictive behaviours: personality factors related to substance use, gambling and computer gaming. Eur Addict Res. 2012;18(4):167–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000335662.

Li JB, Lau JTF, Mo PKH, Su XF, Tang J, Qin ZG, Gross DL. Insomnia partially mediated the association between problematic internet use and depression among secondary school students in China. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):554–63. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.085.

Cao F, Su L. Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: prevalence and psychological features. Child. 2007;33(3):275–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00715.x.

Gecaite-Stonciene J, Saudargiene A, Pranckeviciene A, Liaugaudaite V, Griskova-Bulanova I, Simkute D, Naginiene R, Dainauskas LL, Ceidaite G, Burkauskas J. Impulsivity mediates associations between problematic internet use, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in students: a cross-sectional COVID-19 study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:634464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.634464.

Bener A, Bhugra D. Lifestyle and depressive risk factors associated with problematic internet use in adolescents in an Arabian Gulf culture. J Addict Med. 2013;7(4):236–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182926b1f.

Nielsen P, Favez N, Rigter H. Parental and family factors associated with problematic gaming and problematic internet use in adolescents: A systematic literature review. Curr Addict Rep. 2020;7:365–86.

Alt D, Boniel-Nissim M. Parent–adolescent communication and problematic internet use: the mediating role of fear of missing out (FoMO). J Fam Issues. 2018;39(13):3391–409.

Sela Y, Zach M, Amichay-Hamburger Y, Mishali M, Omer H. Family environment and problematic internet use among adolescents: the mediating roles of depression and fear of missing out. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;106:106226.

Family systems theory, attachment theory, and culture. Family process, 41(3), 328–350.

National Burean of Statistics. The Seventh National Population Census. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/ztjc/zdtjgz/zgrkpc/dqcrkpc/. Accessed 1 June 2022.

Laconi S, Urbán R, Kaliszewska-Czeremska K, Kuss DJ, Gnisci A, Sergi I, Barke A, Jeromin F, Groth J, Gamez-Guadix M, Ozcan NK, Siomos K, Floros GD, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z, Király O. Psychometric Evaluation of the Nine-Item Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ-9) in Nine European samples of internet users. Front Psych. 2019;10:136. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00136.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Costantini L, Pasquarella C, Odone A, Colucci ME, Costanza A, Serafini G, Aguglia A, Belvederi Murri M, Brakoulias V, Amore M, Ghaemi SN, Amerio A. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:473–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.131.

Chilcot J, Rayner L, Lee W, Price A, Goodwin L, Monroe B, Sykes N, Hansford P, Hotopf M. The factor structure of the PHQ-9 in palliative care. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(1):60–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.012.

Joreskog, K. Dag S÷ rbom (1988)," LISREL 7: A Guide to the Program and Application," Chicago, SPSS.

Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50.

Chin WW. Commentary: issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. Manag Inf Syst Q. 1998;22(1):7–16.

Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Browne MW. Asymptotically distribution-free methods for the analysis of covariance structures. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1984;37(Pt 1):62–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1984.tb00789.x.

Bollen KA, Stine RA. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociolo Methods Res. 1992;21(2):205–29.

Zhou HY, Zhu WQ, Xiao WY, Huang YT, Ju K, Zheng H, Yan C. Feeling unloved is the most robust sign of adolescent depression linking to family communication patterns. J Res Adolescence. 2023;33(2):418–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12813.

Schou Andreassen C, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2016;30(2):252–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160.

Jiménez TI, Estévez E, Velilla CM, Martín-Albo J, Martínez ML. Family communication and verbal child-to-parent violence among adolescents: the mediating role of perceived stress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224538.

Carpenter AL, Elkins RM, Kerns C, Chou T, Greif Green J, Comer JS. Event-related household discussions following the boston marathon bombing and associated posttraumatic stress among area youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(3):331–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1063432.

Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma G, Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429.

Hernandez RA, Colaner C. “This is not the hill to die on. Even if we literally could die on this hill”: Examining communication ecologies of uncertainty and family communication about COVID-19. American Behav Sci. 2021;65(7):956–75.

Olson DH, Sprenkle DH, Russell CS. Circumplex model of marital and family system: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Family Process. 1979;18(1):3–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1979.00003.x.

Ritchie LD, Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns: measuring intrapersonal perceptions of interpersonal relationships. Commun Res. 1990;17(4):523–44.

Schrodt P, Ledbetter AM, Ohrt JK. Parental confirmation and affection as mediators of family communication patterns and children’s mental well-being. The J Family Commun. 2007;7(1):23–46.

Ji K, Finkelhor D. A meta-analysis of child physical abuse prevalence in China. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;43:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.11.011.

Calders F, Bijttebier P, Bosmans G, Ceulemans E, Colpin H, Goossens L, Van Den Noortgate W, Verschueren K, Van Leeuwen K. Investigating the interplay between parenting dimensions and styles, and the association with adolescent outcomes. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(3):327–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01349-x.

Liu CR, Wan LP, Liu BP, Jia CX, Liu X. Depressive symptoms mediate the association between maternal authoritarian parenting and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2022;305:213–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.008.

Pereda N, Díaz-Faes DA. Family violence against children in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic: a review of current perspectives and risk factors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00347-1.

Labrum T, Newhill C, Simonsson P, Flores AT. Family conflict and violence by persons with serious mental illness: how clinicians can intervene during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Clin Soc Work J. 2022;50(1):102–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00826-8.

Mithaug, D. E. (1993). Self-regulation theory: How optimal adjustment maximizes gain. Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Roth S, Cohen LJ. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. Am Psychol. 1986;41(7):813–9. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.813.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the people who so generously invested their time in this study. Additionally, thanks to the School of Nursing, North Sichuan Medical College, for providing the funding for this research.

Funding

This research was funded by the National College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program, grant number 202310634021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, XC.H., YN.Z., MM.J., and YB.W.; methodology, XC.H.; formal analysis, XC.H.; investigation, MM.J., YB.W.; resources, MM.J., YB.W.; data curation, YB.W.; writing—original draft preparation, XC.H., YN.Z., XY.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.J., H.C., YQ.D., Y.L., LP.Z., QL.L., SY.L., YY.W., L.Z., MM.J., and YB.W.; visualization, Y.J.; supervision, XC.H., MM.J., and YB.W.; project administration, YB.W.; funding acquisition, QL.L., SY.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University The ethics number is: No.2022-K050. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and also from the legal guardians of the participants who were below 16 years of age.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been updated to remove a redundant affiliation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Xc., Zhang, Yn., Wu, Xy. et al. A cross-sectional study: family communication, anxiety, and depression in adolescents: the mediating role of family violence and problematic internet use. BMC Public Health 23, 1747 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16637-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16637-0