Abstract

Background

Multiple lifestyle risk factors exhibit a stronger association with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) compared to a single factor, emphasizing the necessity of considering them collectively. By integrating these major lifestyle risk factors, we can identify individuals with an overall unhealthy lifestyle, which facilitates the provision of targeted interventions for those at significant risk of NCDs. The aim of this study was to evaluate the socio-demographic correlates of unhealthy lifestyles among adolescents and adults in Ethiopia.

Methods

A national cross-sectional survey, based on the World Health Organization's NCD STEPS instruments, was conducted in Ethiopia. The survey, carried out in 2015, involved a total of 9,800 participants aged between 15 and 69 years. Lifestyle health scores, ranging from 0 (most healthy) to 5 (most unhealthy), were derived considering factors such as daily fruit and vegetable consumption, smoking status, prevalence of overweight/obesity, alcohol intake, and levels of physical activity. An unhealthy lifestyle was defined as the co-occurrence of three or more unhealthy behaviors. To determine the association of socio-demographic factors with unhealthy lifestyles, multivariable logistic regression models were utilized, adjusting for metabolic factors, specifically diabetes and high blood pressure.

Results

Approximately one in eight participants (16.7%) exhibited three or more unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, which included low fruit/vegetable consumption (98.2%), tobacco use (5.4%), excessive alcohol intake (15%), inadequate physical activity (66%), and obesity (2.3%). Factors such as male sex, urban residency, older age, being married or in a common-law relationship, and a higher income were associated with these unhealthy lifestyles. On the other hand, a higher educational status was associated with lower odds of these behaviors.

Conclusion

In our analysis, we observed a higher prevalence of concurrent unhealthy lifestyles. Socio-demographic characteristics, such as sex, age, marital status, residence, income, and education, were found to correlate with individuals' lifestyles. Consequently, tailored interventions are imperative to mitigate the burden of unhealthy lifestyles in Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes, are the most prevalent type of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). These diseases are responsible for 80% of premature NCD-related deaths worldwide [1], leading to over 41 million deaths every year [2, 3]. Since 2005, the burden of NCDs has increased by almost 14% due to several factors, including changes in lifestyle and behavior, and increasing urbanization. Low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) bear the brunt of this impact, contributing to approximately 77% of all NCD-related deaths and 85% of premature deaths (aged 30–69 years) [2].

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent a significant burden that disproportionately impacts impoverished communities, a phenomenon that is notably more pronounced in low-to-middle income countries (LMICs) [4] due to the double burden of infectious disease and weak health care system [5, 6]. Four modifiable lifestyle risk factors – tobacco use, harmful alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and unhealthy diet – are primary contributors to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Tobacco use alone accounts for over 7.2 million deaths annually [7]. Excess salt or sodium intake is responsible for 4.1 million deaths, while harmful alcohol use and insufficient physical activity are attributed to 3.3 million and 1.6 million deaths respectively [8]. These lifestyle risk factors are associated with metabolic risk factors such as overweight and obesity, elevated blood pressure, and raised blood glucose, which contribute to the development of NCDs [7, 8]. Thus, global strategies to control NCDs focus on addressing these modifiable lifestyle factors [2].

The sustainable development goal (SDG) target 3.4 is aimed at reducing NCD-related premature death by one-third by 2030 [9]. In alignment with this goal, Ethiopia set targets to reduce NCD-related premature deaths by 12.5% [10]. Although deaths attributed to NCDs in Ethiopia decreased by 37% between 1990 and 2015, there is limited knowledge regarding the burden of unhealthy lifestyle factors and their association with socio-demographic and metabolic factors [11]. This suggests that national strategies require full implementation of interventions and need to prioritize people with unhealthy lifestyle factors associated with NCDs.

The evidence for the benefit of healthy behaviours on reducing NCDs is well established [12,13,14]. Multiple lifestyle risk factors are more likely to exhibit a stronger association with NCDs than a single lifestyle-related factor. Hence, it would be particularly beneficial to amalgamate all major all the major lifestyle risk factors to ascertain an individual's overall unhealthy lifestyle. This approach would allow us to identify individuals at significant risk for NCDs and include them in targeted intervention programs [15]. Recent attention has been drawn to the understanding of socio-demographic factors, such as income inequality in relation to unhealthy lifestyles [16,17,18]. Prioritizing non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention interventions towards socio-demographic groups with multiple unhealthy lifestyle factors could be a cost-effective strategy [19, 20]. However, to our knowledge, no study has shown the socio-demographic correlates of multiple unhealthy lifestyles in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aims to determine the prevalence of unhealthy lifestyles and their association with socio-demographic groups. Additionally, we also evaluated the association of unhealthy lifestyles with diabetes and hypertension.

Methods

Data source

Individual-level data collected from a community-based cross-sectional survey were used. The survey was conducted in 2015 by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute in collaboration with the Federal Ethiopian Ministry of Health (FMOH) and World Health Organization (WHO) using the NCD STEPS instrument [21]. The STEPS survey methods are described in detail elsewhere [22]. Briefly, the survey was conducted among 9, 800 adolescents and adults aged between 15 and 69 years. The survey contains information about the socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics (STEP I); physical measurements for blood pressure, overweight, and obesity were calculated (STEP II); and included biochemical measurement for diabetes, raised blood glucose, and abnormal lipid level (STEP III) (Supplementary information).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic data such as age (15 – 29, 30 – 44, 45 – 59, and 60 – 69 years), sex, residence (urban or rural), education (no formal schooling, primary school completed, secondary school completed, and college/University completed), marital status (single, married, and common-law), and income (≤ 12,000, 12,000–23, 299, ≥ 23,300 Birr) were assessed. Participants were recruited from all administrative regions of Ethiopia.

Unhealthy lifestyle score

Based on previous studies [23], insufficient physical activity, tobacco use, excessive intake of alcohol, and inadequate serving of fruit and vegetable intake, and overweight/obesity were used to construct unhealthy lifestyle scores as an outcome variable.

Insufficient physical activity

Physical activity was assessed based on the total time spent on physical activity per day at work, including transport and recreational settings. It was measured using the metabolic equivalent time (MET) in minutes per week spent in physical activity. According to the WHO recommendation on physical activity, performing an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity below 600 MET-minutes per week was considered as insufficient physical activity [24].

Excessive alcohol intake

Alcohol consumption was measured in terms of current and previous drinking (i.e., ever or within 12 months of the interview period) using the concept of a standard drink i.e., any drink containing about 10 g of pure alcohol. Men who reported four or more standard units per day and women who reported three and more standard units per day “ever” or within the last 12 months were classified as having excessive use of alcohol [25].

Current smoking

Tobacco use was assessed in terms of current and previous smoking status, duration of smoking, the quantity of tobacco use, smokeless tobacco use, and exposure to second-hand smoking. Respondents who replied, ‘Yes’ for the question “do you smoke cigarettes (any tobacco product)?” were categorized as “current tobacco users”.

Dietary intake

Fruit and vegetable intake were used as a surrogate variable for overall dietary quality as there was no comprehensive data on dietary intake. Consumption of fruit and vegetables was assessed in terms of the number of servings, with a serving being equal to 400 g [26]. Participants who reported consumptions of less than five servings of fruit or vegetables per day during the last 30 days of the interview were considered as having a suboptimal diet [27].

Metabolic factors

Overweight/obesity: a respondent's height (cm) and weight (kg) measurements were taken to calculate body mass index (BMI). BMI was calculated as the respondent's weight in kilograms divided by the square of the respondent's height in meters (kg/m2). Participants with BMI 25–29.9 and ≥ 30 kg/m2 were classified as overweight and obese, respectively.

Diabetes

Blood glucose measurements were taken to assess diabetes. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose value: > = 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dl) or currently taking medication/s for diabetes.

High blood pressure

Both systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure were measured three times and the mean values were taken for this analysis. High blood pressure was defined as SBP > = 140 mmHg and/or DBP > = 90, or currently taking medication for high blood pressure.

Unhealthy lifestyle scores for each participant were calculated as the sum of the five distinct factors. The potential scores ranged from 0, representing the lowest degree of unhealthy behavior, to 5, indicating the highest. These high scores reflect a significant co-occurrence of risk factors. We defined an unhealthy lifestyle as the presence of three or more risk factors. Given that approximately three-quarters of the survey respondents hailed from rural areas of Ethiopia, a substantial number of participants likely harbored at least two unhealthy lifestyle risk factors. This is because of the fact that consumption of a homemade, beer-like traditional alcohol known as 'Tela' is prevalent in rural areas, coupled with the typically low levels of nutritional knowledge and dietary diversity among rural inhabitants [28].

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were analysed by examining the proportion of categorical variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous and symmetrically distributed data, and median and interquartile ranges (25th and 75th percentiles) for continuous and asymmetric data. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine the association of socio-demographic factors with unhealthy lifestyle using crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). When estimating the adjusted OR for sociodemographic factors, we accounted for metabolic factors, including diabetes and high blood pressure. A p-value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant for the association between socio-demographic factors and co-occurrence of unhealthy NCD lifestyle risk factors. Chi-square test was conducted to assess the association between unhealthy lifestyle as exposure and diabetes and hypertension as outcomes (separately). Data management and analysis were performed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and R (version 3.6.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Of the analysis included a total of 9,800 participants, with a response rate of 95.5%. Three in five participants were females (59.4%), 78.8% did not attend formal schooling and 72.6% were rural residents. The median age of the study participants was 32 years (25th and 75th percentile: 25, 44 y). Two-thirds of the participants (66.0%) had insufficient physical activity per week, 15.3% were classified as they drank excess alcohol per day based on their response and 5.4% of participants were current smokers. Almost all had inadequate fruit and vegetable intake (98.2%) and 10% were overweight/obese. There were significant differences in the prevalence of almost all unhealthy behaviours across sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1).

Co-occurrences of unhealthy lifestyles

Table 2 shows sociodemographic characteristics across unhealthy lifestyle scores. The median unhealthy lifestyle score was three. Only three participants had five risk factors (we added to those who had four risk factors due to the small sample size). One in six participants (16.7%, 95% CI: 16.01, 17.58) had three or more unhealthy lifestyle factors. Significant differences were observed in unhealthy lifestyle scores across various sociodemographic categories. A higher unhealthy lifestyle score was common in older age rural participants (Fig. 1). In most regional administration areas, participants had a least 2 unhealthy lifestyle factors (Fig. 2).

Factors associated with unhealthy lifestyles

Our study demonstrated that males had higher odds of maintaining unhealthy lifestyles compared to females (AOR = 2.27, 95% CI: 1.95, 2.63). Additionally, urban residents were more likely to lead unhealthy lifestyles compared to their rural counterparts (AOR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.50, 2.06). Notably, the odds of having an unhealthy lifestyle increased with age: participants in the age group of 30–44 years showed higher odds (AOR = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.38, 1.99), those in the 45–59 years age group displayed even higher odds (AOR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.60, 2.47), and individuals in the 60–69 years age group also demonstrated high odds (AOR = 1.59, 95%CI = 1.18, 2.15) (Table 3).

Compared to single individuals, being married was associated with higher odds of adopting unhealthy lifestyles (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.04, 1.68). Similarly, individuals with an annual income exceeding 12,000 ETB demonstrated a positive correlation with unhealthy lifestyle choices (AOR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.20, 1.76 for an income range of 12,000 to 23,299 ETB and AOR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.12, 1.75 for income of 23,300 ETB and above). However, participants who had achieved a college education or higher presented lower odds of leading an unhealthy lifestyle in comparison to those without formal education (AOR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.55, 0.97) (Table 3).

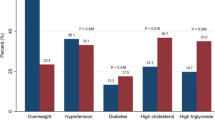

Unhealthy lifestyle factors, diabetes, and hypertension

There were significant associations between excessive alcohol intake and overweight/obesity with diabetes (χ2 = 4.25, p < 0.04 for excessive alcohol intake and χ2 = 69.24, p < 0.001 for overweight/obesity). Similarly, there were significant associations between excessive alcohol intake and overweight/obesity with high blood pressure (χ2 = 10.30, p = 0.001 for excessive alcohol intake and χ2 = 286.78, p < 0.001 for overweight/obesity) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this research, we assessed the socio-demographic determinants of detrimental lifestyle behaviors in Ethiopia, emphasizing tobacco use, heavy alcohol consumption, sedentary behavior, insufficient daily intake of fruits and vegetables, and instances of overweight and obesity. An elevated occurrence of these harmful lifestyle behaviors was observed, with approximately 16.7% of the study population exhibiting at least three of these behaviors. Notably, the prevalence of such lifestyles demonstrated significant associations with variables such as gender, marital status, urban dwelling, advanced age, and a higher income bracket. The findings from this research imply a critical need for targeted health interventions in Ethiopia, focusing on demographics exhibiting a higher prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as urban, older, wealthier individuals and specific gender and marital statuses.

Several large, nationally representative surveys, such as the Global Burden of Disease study, have identified that a significant proportion of NCDs and disability-adjusted life years lost across the globe, including in LMICs are due to mainly modifiable lifestyle factors such as smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and inappropriate alcohol consumption [29]. In our study, we found that participants were more likely to engage in two or more unhealthy behaviours. Previous studies [8, 30, 31] have reported similar findings. A high prevalence and co-occurrence of unhealthy lifestyle factors are associated with high burden of morbidity and premature mortality from chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and some types of cancer [32]. This may eventually lead to healthcare system strain and increased cost of disease management, as well as productivity loss due to illnesses.

Our findings revealed that a high prevalence of co-occurrence of unhealthy lifestyle factors was significantly associated with place of residence. Specifically, participants from urban areas were more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles than their rural counterparts, which is similar with previous studies in Ethiopia [33,34,35] and other African countries [36,37,38]. This disparity can be attributed to the fact that urban areas in developing countries, like Ethiopia, are undergoing economic and social developments that contribute to increased exposure to unfavourable environments and behaviours. These behaviours include sedentary lifestyles, smoking, alcohol consumption, and overweight/obesity.

Similarly, our study showed that the likelihood of co-occurrence of risk factors or unhealthy lifestyle increases among participants with higher income, which is in line with previous studies from Ethiopia, Ghana, and Chile. Risk factors, such as overweight and obesity and low physical activity, were associated with wealthier socioeconomic groups [32, 33, 36]. This is a common occurrence in developing countries, where people tend to consume energy-dense and high-fat foods and follow a sedentary lifestyle as their economic condition improves [36, 39]. However, the study showed participants with higher educational status are more likely to engage in physical activity and have a healthier diet. This finding is similar to a study done in Ghana, where Ghanaian adults were more likely to live a healthier lifestyle with increasing levels of educational attainment [36]. This may be because educated people can easily access educational messages on health and risk factors to choose healthier behaviours.

The study also showed variations in the co-existence of unhealthy lifestyle risk factors by socio-demographic factors such as gender, age, and marital status. We observed that despite mixed findings on gender and the number of unhealthy lifestyles, obesity and insufficient physical activity were higher among females than males, while males had higher risks for excessive alcohol intake and smoking [33, 40]. Likewise, our study showed that older participants were more likely to have an unhealthy lifestyle than younger groups. This finding is in line with other similar studies that have found that the prevalence of unhealthy lifestyles, such as smoking, excessive alcohol drinking, and obesity, increases with age [39, 40]. In our study, those who were married also showed a significant association with higher odds of an unhealthy lifestyle. Evidence from Ethiopia and other developing countries indicates that married people are more likely to adopt a sedentary lifestyle [39, 41, 42].

Overall, our study demonstrates and alarming prevalence of co-occurring unhealthy lifestyle factors in Ethiopia, with individual-level risk factors such as excessive alcohol intake, overweight, and obesity being associated with diabetes and high blood pressure. To address these issues, targeted and evidence-based interventions are needed to promote healthy lifestyle habits.

Implication for policy and practice

Our study examined the co-occurrence of non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia, a country that has undergone rapid socio-economic development and lifestyle changes over the last few decades. While previous studies have documented the prevalence of individual unhealthy lifestyle behaviours, our study is the first to examine how these behaviors co-occur based on sociodemographic characteristics.

Policymakers can use our study as an input to implement comprehensive, policy-level behavioural and public health interventions that promotes healthy lifestyle. By identifying patterns in the co-occurrence of NCD risk factors, our study provides valuable inputs for designing such interventions in Ethiopia. Specifically, our findings highlight the need for context-specific and tailored interventions that take into account sociodemographic factors such as age and sex.

Our study has several strengths, including being the first to examine the co-occurrence unhealthy NCD risk factors and the use of nationwide data collected from a large sample size. However, there are limitations to our findings. One limitation is that the dominant influence of rural areas, due to their larger sample size, may affect the generalizability our results, despite the fact that the prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle issues is primarily observed in urban areas. Additionally, while our study identifies patterns in the co-occurrence of NCD risk factors, further research is commended to determine causality and the effectiveness of interventions.

Overall, our study contributes to a better understanding of the epidemiological transition in Ethiopia and the need for interventions that address the growing burden of NCDs. By designing comprehensive and coordinated interventions that consider the co-occurrence of multiple risk factors, policymakers can help reduce the burden on the country's healthcare system and promote healthier lifestyles for all Ethiopians.

Conclusion

In our investigation, it was observed that detrimental lifestyle habits are widespread, affecting a significant fraction of the population; approximately one out of every eight participants manifested three or more such habits. We discerned considerable variation in the distribution of these unhealthy lifestyle factors, which was closely tied to sociodemographic attributes. A more advanced level of education correlated with reduced likelihood of poor lifestyle habits. Additionally, conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure showed a positive correlation with excessive alcohol consumption and overweight/obesity. These observations underscore the imperative for strategic interventions that encourage healthier lifestyle choices, particularly among those with lower educational attainment, as they appear to be at a higher risk. It is crucial that attempts to rectify these detrimental behaviours consider the social and economic factors of individuals to ensure the development and implementation of interventions that successfully tackle the underlying factors of such behaviours.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Global health estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization; 2014.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. 2018.

Bloom DE, Chisholm D, Jané-Llopis E, Prettner K, Stein A, Feigl A. From burden to “Best Buys”: reducing the economic impact of non-communicable diseases. World Health Org: Geneva, Switzerland; 2011.

Bloom DE, Cafiero E, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, Feigl AB, Gaziano T, Hamandi A, Mowafi M. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. In.: Program on the Global Demography of Aging; 2012.

Bollyky TJ, Templin T, Cohen M, Dieleman JL. Lower-income countries that face the most rapid shift in noncommunicable disease burden are also the least prepared. Health Aff. 2017;36(11):1866–75.

World Health Organization. WHO global coordination mechanism on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: progress report 2014–2016. Geneva: WHO; 2017.

GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–724.

Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coates MM. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544.

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Health sector transformation plan (2015/16–2019/20). In: Federal Ministry of Health Addis Ababa. Ethiopia: Ministry of Health; 2015.

Misganaw A, Haregu TN, Deribe K, Tessema GA, Deribew A, Melaku YA, Amare AT, Abera SF, Gedefaw M, Dessalegn M. National mortality burden due to communicable, non-communicable, and other diseases in Ethiopia, 1990–2015: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Popul Health Metrics. 2017;15(1):29.

Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Kröger J, Schienkiewitz A, Weikert C, Boeing H. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1355–62.

Nugent R, Bertram MY, Jan S, Niessen LW, Sassi F, Jamison DT, Pier EG, Beaglehole R. Investing in non-communicable disease prevention and management to advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet. 2018;391(10134):2029–35.

Yang Z-Y, Yang Z, Zhu L, Qiu C. Human behaviors determine health: strategic thoughts on the prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Int J Behav Med. 2011;18(4):295–301.

Poortinga W. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev Med. 2007;44(2):124–8.

Al-Hanawi MK, Keetile M. Socio-economic and demographic correlates of non-communicable disease risk factors among adults in Saudi Arabia. Front Med. 2021;8:605912.

El Ghardallou M, Maatoug J, Harrabi I, Fredj SB, Jihene S, Dendana E, et al. Socio-demographic association of non communicable diseases’ risk factors in a representative population of school children: a cross-sectional study in Sousse (Tunisia). Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017;29(5):20150109. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0109.

Ryu SY, Park J, Choi SW, Han MA. Associations between socio-demographic characteristics and healthy lifestyles in Korean Adults: the result of the 2010 Community Health Survey. J Prev Med Public Health. 2014;47(2):113.

Lv J, Liu Q, Ren Y, Gong T, Wang S, Li L. the Community Interventions for Health c: socio-demographic association of multiple modifiable lifestyle risk factors and their clustering in a representative urban population of adults: a cross-sectional study in Hangzhou, China. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):40.

World Health Organization. Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

World Health Organization. WHO STEPS surveillance manual: the WHO STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance. In.: World Health Organization; 2005.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI). Ethiopia steps report on risk factors for Non-Communicable Disease and prevalence of selected NCDs. Addis Ababa: EPHI; 2016.

Li Y, Pan A, Wang DD, Liu X, Dhana K, Franco OH, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Stampfer M, Willett WC. Impact of healthy lifestyle factors on life expectancies in the US population. Circulation. 2018;138(4):345–55.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. In. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Niaaa A. Understanding the impact of alcohol on human Hhealth and well-being. Bethesda, MD: NIAAA; 2017.

Agudo A, Joint F. Measuring intake of fruit and vegetables [electronic resource]. World Health Organization; 2005.

Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;916:1–149.

Hirvonen K. Rural–urban differences in children’s dietary diversity in Ethiopia: a poisson decomposition analysis. Econ Lett. 2016;147:12–5.

Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, Barengo NC, Beaton AZ, Benjamin EJ, Benziger CP, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982–3021.

Krokstad S, Ding D, Grunseit AC, Sund ER, Holmen TL, Rangul V, Bauman A. Multiple lifestyle behaviours and mortality, findings from a large population-based Norwegian cohort study - The HUNT Study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):58.

Rizzuto D, Fratiglioni L. Lifestyle factors related to mortality and survival: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;60(4):327–35.

Al-Maskari F. Lifestyle diseases: an economic burden on the health services. UN Chronicle The Magazine of the United Nations. 2010.

Memirie ST, Dagnaw WW, Habtemariam MK, Bekele A, Yadeta D, Bekele A, Bekele W, Gedefaw M, Assefa M, Tolla MT, et al. Addressing the Impact of Noncommunicable Diseases and Injuries (NCDIs) in Ethiopia: Findings and Recommendations from the Ethiopia NCDI Commission. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022;32(1):161–80.

Tesfay FH, Backholer K, Zorbas C, Bowe SJ, Alston L, Bennett CM. The magnitude of NCD risk factors in ethiopia: meta-analysis and systematic review of evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5316.

Zenu S, Abebe E, Dessie Y, Debalke R, Berkessa T, Reshad M. Co-occurrence of behavioral risk factors of non-communicable diseases and social determinants among adults in urban centers of Southwestern Ethiopia in 2020: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1561–70.

Tagoe HA, Dake FAA. Healthy lifestyle behaviour among Ghanaian adults in the phase of a health policy change. Glob Health. 2011;7(1):7.

Kingue S, Ngoe CN, Menanga AP, Jingi AM, Noubiap JJN, Fesuh B, Nouedoui C, Andze G, Muna WF. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension in urban areas of Cameroon: a nationwide population-based cross-sectional study. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17(10):819–24.

Rawal LB, Biswas T, Khandker NN, Saha SR, Bidat Chowdhury MM, Khan ANS, Chowdhury EH, Renzaho A. Non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factors and diabetes among adults living in slum areas of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0184967.

Abrha S, Shiferaw S, Ahmed KY. Overweight and obesity and its socio-demographic correlates among urban Ethiopian women: evidence from the 2011 EDHS. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):636.

Peer N, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Steyn N, Steyn K. Urban–rural and gender differences in tobacco and alcohol use, diet and physical activity among young black South Africans between 1998 and 2003. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):19216.

Gichu M, Asiki G, Juma P, Kibachio J, Kyobutungi C, Ogola E. Prevalence and predictors of physical inactivity levels among Kenyan adults (18–69 years): an analysis of STEPS survey 2015. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(3):1217.

Cavazzotto TG, de Lima Stavinski NG, Queiroga MR, da Silva MP, Cyrino ES, Serassuelo Junior H, Vieira ER. Age and sex-related associations between marital status, physical activity and TV time. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):502.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) for providing the data, Australian Based Ethiopian Researcher Network (ABReN) for organizing this research team and facilitating the data request, and the Curtin University for ethical approval.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant. YAM is supported by The National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Investigator Grant (2009776), which is not directly connected to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.A.G, D.N.K, K.A.A, K.Y.A, and Y.A.M; methodology and data analysis: Y.A.G, D.N.K & Y.A.M; writing—original draft preparation: Y.A.G, Y.A.M, D.A.E, H.G.T, and A.T.G; writing—review and editing, Y.A.G & Y.A.M; visualization: Y.A.G; D.N.K, K.A.A, Y.A, and B.M.Z reviewed and provided editorial feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research uses national survey secondary data; therefore, ethical approval was not required. Permission to access the data was obtained from EPHI.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gelaw, Y.A., Koye, D.N., Alene, K.A. et al. Socio-demographic correlates of unhealthy lifestyle in Ethiopia: a secondary analysis of a national survey. BMC Public Health 23, 1528 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16436-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16436-7