Abstract

Background:

Life satisfaction (LS), a useful construct in the study of psycho-social well-being, is an important indicator of healthy aging. With a view to investigate whether the improved longevity in India is accompanied by commensurate levels of well-being and contentment among the older adults , this study aimed to examine (1) the association between LS and sleep quality among older Indian adults aged 60 years and above (2) the mediating role of depression that accounts for the association and (3) the moderating role of functional limitation in this mediation.

Methods:

Cross-sectional data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI), Wave-1 (2017-18) was used. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate the pair-wise relationship between sleep quality, depressive symptoms, functional limitation, and LS. Structural Equation Model was employed to analyse the moderated-mediated association between sleep quality and the level of LS.

Results:

Sleep quality had a direct effect (β=-0.12) as well as an indirect effect (β=-0.024) via depressive symptoms on LS, accounting for 83.6 and 16.4 per cent of the total effects, respectively. Also, the interaction term between poor seep quality and functional limitation was positive (β = 0.03, p < 0.001) in determining depressive symptoms, suggesting that higher level of functional limitation aggravated the indirect effect of poor sleep quality on LS.

Conclusion:

The findings of the study suggested that ensuring both the physical as well as the mental well-being of the population during the life course may confer in later life the desired level of life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With improvement in longevity, India is experiencing a change in its demographic landscape as the proportion of older adults in the total population is gradually increasing. As per the census of India, 2011, older persons aged 60 years or above accounted for 8.6% of the overall population [1]. India has, thus, acquired the label of “an ageing nation”. The share of the older population aged 60 + years is projected to further rise to 19.5% (319 million) by 2050 [2]. Life expectancy at ages 60 and 80 in India have observed considerable improvement and currently stand at 18 and 7 years respectively, projected to rise further to 21 and 8.5 years, respectively by 2050 [2]. While this improved longevity is indicative of an epidemiological achievement of the country, it also poses the challenge of ensuring ‘healthy aging’ to the policy makers. It needs to be investigated whether the longer life, due to improvement in longevity, is accompanied by better levels of well-being and contentment among the older population . Studies have found that greater life satisfaction is highly associated with improved physical and mental health conditions and longevity, therefore, it is considered a universal indicator of successful ageing [3, 4]. In this regard, life satisfaction (LS), a useful construct in the study of psycho-social well-being, is an important indicator of prosperous aging [5, 6].

Life satisfaction, an indicator of happiness, is defined as a cognitive judgment or subjective attitude towards one’s life [7]. It measures the degree of coherence between the desired goals and the actual outcome achieved [8]. Higher life satisfaction is reported when the life conditions are evaluated in line with one’s expectations [9]. Life satisfaction is a component of subjective well-being, where the presence of positive affect and the absence of negative affect are the affective components [10].

The findings of studies on the determinants of life satisfaction are multi-pronged [11,12,13,14]. The negative impact of poor sleep quality on life satisfaction has been observed and demonstrated among older adults [15,16,17]. Sleep problems are highly prevalent among older adults [14, 18]. The strong association between emotion and sleep, which is documented in previous studies, is increasingly recognized as an important area of research [19]. However, the source of dissatisfaction is less likely due to the changes in the structure and pattern of sleep that occur with the aging process but is more likely associated with the physical and the mental health among older adults [18, 20].

Life dissatisfaction is an effective indicator of an individual’s exposure to depression, suicidal tendencies, and other psychiatric illnesses and disabilities [21]. Among these, depression is highly prevalent among older people, coupled with poor sleep quality [22, 23]. Several studies have indicated that having a depressive disorder adversely affects the quality and satisfaction of life among older adults 24,25,26,27. Moreover, sleep quality has been found to be associated with mental health [28, 29]. Empirical evidence shows a negative impact of poor sleep quality and sleep duration on psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis [30].

In addition to mental health, previous studies have also well documented the association of higher life satisfaction with better physical health [21, 31,32,33], self-rated health [34], and longevity [4]. The loss of functional capacity at older ages affects the satisfaction of life and influences individuals to such a degree that they moderate their expression of well-being [35]. Life satisfaction and mental health are highly associated with each other, and additionally, self-rated health and limited functionality are significant contributors to depressive symptoms and psychological distress [36]. Living alone and decline in functional health are recognized to have negative impacts on older adults’ life satisfaction [11]. Disability prevents older adults from performing their social roles and daily routines, which subsequently influences their life satisfaction levels [31].

In order to achieve healthy aging in later life, interventions should be developed to enhance positive psychological factors such as life satisfaction and quality of life as well as to reduce mental health symptoms and sleep disturbance [37]. However, unlike in the developed world, there is a lack of studies addressing the factors affecting life satisfaction among older adults in developing societies such as India. In the traditional Asian cultural norms, due to the existence of the traditional joint family system, older adults are supposed to live with their children under the same roof and (or) other family members, which as a result provides social security, emotional and economic support to the older adults [38,39,40]. But changes in living arrangements, and family structures are affecting the health and life satisfaction of older adults [41, 86]. Moreover, due to the lack of effective social institutions and broad-based pension or social security schemes in developing countries, the factors affecting the life satisfaction of older adults in developing countries might differ from those affecting older population of the developed world [38, 42].

Given this backdrop, the present study makes an attempt to draw evidence from the data collected by a recent national-level sample survey to shed light on the nature of the linkage between life satisfaction, sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and functional limitation. Specifically, the central objectives of this study are to examine (1) the relationship between LS and sleep quality among older Indian adults aged 60 years and above, (2) the mediating role of depression that accounts for the association, and (3) the moderating role of functional limitation in this mediation. This paper examines the relationship between various covariates of LS among older adults in India on the basis of the following hypothesis: mental health mediates the association between sleep quality and life satisfaction, and this mediation process is moderated by functional limitations.

Materials and methods

Data

Data collected through the nationally representative large-scale sample survey, Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI), Wave 1), conducted during 2017-18, has been used for the present study. The LASI adopted a multistage-stratified area probability cluster sampling design and surveyed 42,949 households across all states and UTs of India (except Sikkim), collecting data from a total sample of 72,250 older adults aged 45 and above (including their spouses irrespective of age). The survey collected data on various aspects of older persons’ health and well-being, including but not limited to disease burden, health-seeking behaviour, psycho-social well-being, and socioeconomic security. In addition, the LASI also conducted assessments of the respondents’ physiological, performance-based, anthropometric, and blood-molecular measurements using several internationally validated biomarker tests. The present analysis considers only the respondents aged 60 years or above (n = 31,464; mean age = 67.9 ± 7.5 years). The detailed profile of the study population is presented in Table 1.

Measures

Outcome Variable: life satisfaction

The LASI asked the respondents to rate a set of 5 (affirmative) statements about satisfaction in life on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to gauge their levels of contentment in life. The scale reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.90 indicated excellent internal consistency [43]. A composite score (ranging between 1 and 7) was obtained for each individual for the present analysis. The higher the score, the higher would be the level of life satisfaction.

Predictor Variable: sleep quality

The frequency of sleep disturbances experienced during the past one month was assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = frequently, i.e., ≥ 5 nights per week), including 5 items in the LASI. The Cronbach’s alpha measured 0.83, suggesting good reliability. A composite score for sleep quality (ranging from 1 to 4) was constructed, a higher score indicating poorer quality of sleep.

Mediator Variable: depressive symptoms

The analysis uses the responses of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview- Short Form (CIDI-SF) scale, one of the two internationally validated and comparable tools (the other being the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale) employed by the LASI to assess depressive symptoms and diagnose probable major depression [44, 45]. LASI adopted the definition of depression as ‘an extended period of time (at least two weeks) in which a person experiences a depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in activities that were once enjoyed [46]. Accordingly, the survey asked three screening questions to filter out those without any or persistent episodes of depressive tendencies. Finally, those who reported having ‘felt sad, blue, or depressed’ (lasting for two weeks or more in a row, all day long/ most of the day, every day/ almost every day) were asked to indicate a ‘yes’=1 or a ‘no’=0 to having 7 different depressive symptoms. The reliability score of 0.70 suggested acceptable internal consistency. A composite score was calculated (ranging between 0 and 7). The higher the score, the greater is the number of depressive symptoms.

Moderator variable: functional limitation

The LASI assessed difficulty faced in performing a total of 13 Activities of Daily Living (ADL) due to a physical, mental, emotional, or memory problem. The respondents were asked to indicate a ‘yes’=1 or a ‘no’=0 to having difficulties (that had lasted for more than three months) in each of the activities. The reliability score for the items in the scale was excellent, equal to 0.91. A composite score was calculated (ranging between 0 and 13). The higher the score, the greater the functional limitation.

The items included in each of the measures described above are listed in Table 2.

Covariates

Based on previous literature on the determinants of Life Satisfaction, five broad domains of covariates have been identified and included in the analysis as controls [4, 11, 25, 36, 42, 47,48,49]. These domains pertain to demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, religion, social group); social support factor (living arrangement); socioeconomic factors (residence, economic status, education, work status); health conditions (chronic ailments, impairments); and financial empowerment (intra-household involvement in financial matters).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations) of each of the measures were calculated along with Pearson’s correlation coefficients to investigate the pair-wise relationship between sleep quality, depressive symptoms, functional limitation, and life satisfaction. Mean comparison tests were conducted to examine the inter-group mean differences in the respective measures. The t-statistics of the mean differences were tested for statistical significance by two-tailed p-values.

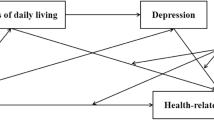

It is hypothesised that some of the effect of the predictor (sleep quality) on the outcome (life satisfaction), passes through the mediator (depressive symptoms), constituting an indirect effect. Moreover, functional limitation interacts with sleep quality such that the effect of sleep quality on depressive symptoms changes depending on the level of functional limitation (moderator), thereby constituting a conditional indirect effect [50]. The analytical framework of this moderated mediation process is presented in Fig. 1. Structural Equation Model (SEM) was employed to analyse the moderated-mediated association between sleep quality and the level of life satisfaction. The SEM generated path coefficients from two different ordinary least squares (OLS) models; one with depressive symptoms (mediator) as the response variable and the other with life satisfaction (outcome) as the response variable. The covariates were controlled for in both the models. Conditional indirect effects were obtained by multiplying coefficients from the SEMs at three different values of the moderator variable; mean – 1 standard deviation or SD (low moderator), mean (medium moderator), and mean + 1 SD (high moderator). Bootstrap estimates of standard errors and bias-corrected confidence intervals were computed with 5000 repetitions of resampling. The SEM can be expressed in a simplified form as follows:

Where, m = mediator; x = predictor; y = outcome; w = moderator; cn are the covariates; an and bn are the respective regression coefficients; εn are the error terms; b2 = direct effect; a1* b1 = indirect effect; a1(b1 + a3*w) = conditional indirect effect (that varies with varying values of the moderator).

Since the missing values were at random, observations with missing data in categorical variables were excluded from the analysis. Missing values in continuous variables were imputed by the mean of the observed values. Sample weights as provided by the LASI, 2017-18 [87] were applied in the analyses to account for selection probabilities and adjust for non-response. All the statistical analyses were carried out using the software STATA (version 16).

Results

Inter-correlations between the model variables

The results of the correlation analysis, presented in Table 3, revealed that poor sleep quality is positively correlated with depressive symptoms. Functional limitation is positively correlated with both poor sleep quality and depressive symptoms. Poor sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and functional limitation are all negatively correlated with life satisfaction. All the inter-correlations were highly statistically significant, albeit being weak or moderate.

Mean scores of core model-variables by select covariates

The results of the bivariate analysis of the mean differences between different demographic and socioeconomic groups are presented in Table 4. Female older persons had higher levels of poor sleep quality, depressive symptoms and functional limitations, and a lower level of life satisfaction than the males. Those currently married had greater life satisfaction than those who were not. Older persons living alone had higher levels of depressive symptoms than those living with spouse and/or children or others. The level of functional limitation differed among the illiterate and literate older persons , disfavouring the illiterates. Older persons with at least one impairment had a lower level of life satisfaction compared to those without any. Also, those involved in their intra-household decision-making on financial matters had a better quality of sleep, lower levels of depressive symptoms and functional limitations, and higher life satisfaction than those without such involvement.

Mediation effect of depressive symptoms on the association between sleep quality and life satisfaction, moderated by functional limitation

The results of the regression analysis, presented in Table 5, showed that poor sleep quality had negative effect (β=-0.12, p < 0.001) on life satisfaction. Poor sleep quality also had a positive effect (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) on depressive symptoms, which in turn had a negative effect (β=-0.09, p < 0.001) on life satisfaction. Thus, sleep quality had a direct effect (β=-0.12) as well as an indirect effect (β=-0.024) via depressive symptoms on life satisfaction, accounting for 83.6 and 16.4% of the total effects, respectively (Table 5). The standardised coefficients of the moderated mediation analysis have been presented in Fig. 2. Also, while functional limitation had a negative effect on life satisfaction (β=-0.029, p < 0.001), its effect on depressive symptoms was statistically insignificant. However, the interaction term between poor sleep quality and functional limitation was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.03, p < 0.001), suggesting that a higher level of functional limitation aggravated the effect of poor sleep quality on depressive symptoms. This conditional indirect effect was calculated and presented in Table 6 at three different values of functional limitation- low (mean-std dev), medium (mean), and high (mean + std dev).

Living arrangement, place of residence, work status, chronic morbidity, impairment, and involvement in financial matters showed a statistically significant effect on depressive symptoms. Besides, gender, marital status, social group, place of residence, literacy, economic status, and impairment were statistically significant determinants of life satisfaction.

Robustness check

In order to verify whether the moderated mediation relationship between poor sleep quality and life satisfaction is robust to specification changes in our model, we conducted a sensitivity analysis [51] by estimating a set of regressions where the outcome variable was regressed on a set of core variables (included in all the regressions) and every possible combination of certain testing/ non-core/ secondary variables. A total of 4096 (= 212) regression models were estimated for each of the two outcomes of the structural equation model of Table 4, i.e., depressive symptoms and life satisfaction. For the model with depressive symptoms as the outcome, poor sleep quality, functional limitation, and their interaction (multiplicative) term were defined as the three core variables, while for the model with life satisfaction as the dependent variable, depressive symptoms, poor sleep quality, and functional limitation constituted the core variables. All the predictors in Table 4 were considered secondary, except the variables age and age-squared, which were always included in all the regressions. Thus, twelve variables (sex, marital status, social group, religion, living arrangement, place of residence, education, work status, wealth quintile, chronic disease, impairment) were regarded as non-core. The results of the sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 7.

The sensitivity analysis revealed that the results remained largely unaffected when one or more predictors were omitted, thereby confirming the robustness of our proposed model. In the case of the model with depressive symptoms as the outcome, the coefficients of the core variables were positive in 100% of the regressions, therefore indicating no instance of sign change in any combination of the testing variables. Similarly, there was zero instance of sign change in the coefficients of the core variables in the model with life satisfaction as the outcome, where the sign was negative in 100% of the regression estimates. The effect of poor sleep quality on depressive symptoms was statistically significant (at 0.05 significance level) in 100% of the cases. Functional limitation was a statistically significant predictor of depression in only 53.4% of the cases. However, the interaction term between poor sleep quality and functional limitation was statistically significant in 100% of the cases. In the model with life satisfaction as the outcome variable, on the other hand, each of the three core predictor variables were statistically significant at 0.05 level 100% of the time in determining life satisfaction among older adults in India.

Discussion

This study explored the associations between life satisfaction and sleep quality and whether depression mediated this association. The study also examined the moderating effect of functional limitation on the association between sleep quality and depression. In this study, it was found that poor sleep quality had a negative effect on life satisfaction. Furthermore, we found that poor sleep quality had a positive effect on depression, which in turn had a negative effect on life satisfaction among older adults aged 60 or above in India. Therefore, sleep quality had both direct and indirect effects on life satisfaction among older adults. The indirect effect was moderated by functional limitation, and a stronger effect was observed in older adults with a higher level of functional limitations. Thus, functional limitation aggravated the effect of poor sleep quality on depressive symptoms. Therefore, both our hypotheses are supported by the findings of this study.

The findings of this study that poor sleep quality was associated with a higher level of depression fall in line with previous studies on older adults [17, 52, 53]. On the other hand, studies have also explored the mediating role of depression in the association between sleep quality and quality of life which is similar to the construct of life satisfaction [54]. Short sleep duration and poor sleep quality at night may lead to daytime tiredness, which increases adverse events and emotions and eventually predisposes individuals to a risk of depression [55]. Moreover, poor sleep quality has been associated with specific health behaviours to cope with stress, such as smoking and drinking alcohol, misuse of medications, and overeating which might increase the risk of depression [56,57,58]. The mediation analyses also indicated a significant mediating effect of mental health on the association between sleep quality and life satisfaction. Meanwhile, a study in China has also demonstrated that short sleep duration and poor sleep quality were inversely associated with life satisfaction and that the associations were partially mediated by the effects of depression [12]. Poor sleep quality affects cognitive and physical function, interaction with family and social relationships, and self-perception of health [59] which in turn can lead to depression. Therefore, poor sleep quality might reduce the life satisfaction of older adults by increasing mental health problems.

Our study also found the association of some of the covariates with life satisfaction to be statistically significant. Life satisfaction was found to be higher for older female adults than males. Researchers have argued that the tendency to report themselves happy is often higher for women than men, as women exhibit a higher capacity to express their emotions [66, 67]. Another study has found that women’s well-being is influenced by education, marital status, and social networks, but men’s happiness depends on occupation status to a large extent [68]. Further studies need to be carried out to understand the gender differential in life satisfaction. Also, older adults belonging to ST/SC social groups had a negative association with life satisfaction which can be a reflection of their social marginalisation [88]. ‘Currently married’ marital status had a positive association with life satisfaction. “Many activities are couple-companionate, undertaken as a couple, with other couples”[60]. Also, the availability of a spouse presumably gives both emotional and economic support.

Older adults living in rural areas had a negative association with life satisfaction. Social welfare programs, pension schemes, and healthcare services are better available in urban areas than in rural areas which might cause lower life satisfaction among older adults living in rural areas [25, 61]. Moreover, socioeconomic factors like illiteracy and poor income of older adults were also negatively associated with life satisfaction. Education and well-being are positively associated as higher income level, productivity, and social status are achieved through education [62]. A person’s happiness and well-being improves with high family income compared to those with lesser family income [63]. Also, an older person with a secure feeling about money and freedom of choice in the present and future has higher life satisfaction [64]. Moreover, older adults with poor income are unable to meet their health expenses for their physical and mental needs, which in turn becomes more stressful for them [65].

The moderated mediation analyses indicated that functional limitation, i.e., ADL moderated the strength of mediating effect of mental health on the association between sleep quality and life satisfaction. Previous studies found that depressive symptoms adversely affect the quality of life, which is a similar construct of life satisfaction through its association with functional limitation, physical health, and mortality [69]. Additionally, limited functionality due to disability exerts influence on psychological well-being, which can subsequently lead to depressive symptoms and psychological distress [36].Individuals with poor mental health would engage in a low-levels of physical activity which would lead to a functional decline and eventually would cause more stress regarding their health status [70], which would further negatively affect the quality of life. Moreover, older adults with functional limitations can be a burden to their family or caregivers which might compromise healthy familial relationships, which in turn may negatively impact the older adults’ life [13, 71]. Also, older adults with a disability are unable to perform social roles and daily routines, which negatively impacts their level of life satisfaction [31].

Additionally, living arrangement, place of residence, work status, chronic morbidity, impairment and involvement in financial matters were found to be statistically significant determinants of depressive symptoms. Older adults who resided in rural areas had a positive association with reporting depressive symptoms. Rural older adults may be overburdened economically to manage their daily living expenses as they are mostly engaged in informal jobs and farming which has no social security and pension schemes [72]. Also, currently working older adults had a positive association with depression. Certain socio-cultural contexts and norms favour retirement as a socially accepted positive status. Thus, retired individuals are more valued than those who still work, which might explain depressive symptoms among working older adults[73]. Moreover, engaging in a job with no optimal conditions or an unsatisfactory job can possibly lead to depression [74].

An interesting finding of our study is that involvement in financial matters was positively associated with reporting depressive symptoms among older adults. This is in contrast to some other studies that have found that financial empowerment or autonomy increases the ability of the adults to take better control of their health and well-being even in their later life [75, 76]. The burden of meeting daily needs even at an older age might lead to depression among older adults. Besides, older adults with a chronic disease or multimorbidity were more susceptible to depression. A chronic disease might lead to loss of functional ability, loss of independence, and negative effects on the inter-personal relationship, ultimately leading to depression [77,78,79]. Additionally, the presence of one or more impairments was positively associated with depression. Physical and mental impairments lead to dependency on others in terms of self-care and other basic needs, restriction in mobility, low social interaction; hence it may ultimately affect an older persons’ psychological well-being [80, 81].

We also found a positive association of the ‘living alone’ status of older adults with reporting depression, consistent with findings of previous studies that showed older adults living alone had higher odds of depression than those living with their spouses and/ or children [78, 82,83,84]. Contrastingly, it has also been found that conflicts within the family might lead to feelings of loneliness, which is a risk factor of depression; hence living with family might not always necessarily be a protective factor against depression [85].

The current study is not without limitations. Firstly, due to the cross-sectional design, causal inferences cannot be drawn from this study. Secondly, the study, due to being based on self-reported data, is constrained by the subjectivity of perception and reporting bias. Hence, longitudinal studies and research using objective information about the respective indicators are better suited for analysing cause and effect. Despite these limitations, our study makes a modest attempt to add to the existing pool of literature on the determinants of life satisfaction in later life. Also, the study draws evidence from a nationally representative sample of older adults, which adds to its strength. The findings of the study revealed that successful ageing can be achieved by working on different pathways through which sleep quality and mental and physical health determine the level of life satisfaction, as was elicited in our analysis. Understanding the predictors of life satisfaction may have important implications for future health outcomes, such as the development of chronic medical conditions and other mental health conditions.

Conclusion

Effective designing of the welfare programmes, policies, and regulations for older adults warrants a better understanding of the relationship between people’s individual characteristics and their perceptions of life satisfaction. Depression should be diagnosed and treated early in order to reduce its adverse effects on life satisfaction. Older adults with functional limitations should be able to access affordable assistive technology, disabled-friendly housing and public spaces, etc., to have the desired level of independence and a sense of dignity in old age. Finally, an effective and efficient social security system is paramount to ensuring successful ageing.

Availability of data and materials

The data (Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-1) used for the present analysis is freely available for academic researchers and can be requested from here: https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/data-request.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- CES-D:

-

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression

- CIDI-SF:

-

Composite International Diagnostic Interview- Short Form

- LASI:

-

Longitudinal Ageing Study in India

- LS:

-

Life Satisfaction

- OLS:

-

Ordinary Least Squares

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Model

References

Census of India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Vol. 2017, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2011.

Nations U. World population prospects 2019 [Internet]. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2019. 2019. 1–39 p. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12283219.

Beutell N. Life satisfaction in relation to work and family. Work Fam Res Netw. 2006.

Tate RB, Lah L, Cuddy TE. Definition of successful aging by elderly Canadian males: The Manitoba follow-up study. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):735–44.

Kanning M, Schlicht W. A bio-psycho-social model of successful aging as shown through the variable “physical activity. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2008;5(2):79–87. ” .

Iyer V. Old age protection in urban agglomeration of a developing economy: An integration analysis. Aging Hum Dev. 2003;1(3):241–50.

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(2):276.

An J-Y, An K, O’connor L, Wexler S. Life satisfaction, self-esteem, and perceived health status among elder Korean women: Focus on living arrangements. J Transcult Nurs. 2008;19(2):151–60.

Kong F, You X. Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Soc Indic Res. 2013;110(1):271–9.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):141–66.

Ng ST, Tey NP, Asadullah MN. What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest-old? Evidence from China. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171799.

Zhi T-F, Sun X-M, Li S-J, Wang Q-S, Cai J, Li L-Z, et al. Associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with life satisfaction in elderly Chinese: The mediating role of depression. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;65:211–7.

Lu N, Spencer M, Sun Q, Lou VWQ. Family social capital and life satisfaction among older adults living alone in urban China: the moderating role of functional health. Aging Ment Health. 2021 Apr;25(4):695–702.

Kim C, Ko H. The impact of self-compassion on mental health, sleep, quality of life and life satisfaction among older adults. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2018;39(6):623–8.

Papi S, Cheraghi M. Relationship between Life Satisfaction and Sleep Quality and Its Dimensions among Older Adults in City of Qom, Iran. Soc Work Public Health. 2021 May;36(4):526–35.

Shin J, Kim JK. How a good sleep predicts life satisfaction: The role of zero-sum beliefs about happiness. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1589.

Lacruz ME, Schmidt-Pokrzywniak A, Dragano N, Moebus S, Deutrich SE, Möhlenkamp S, et al. Depressive symptoms, life satisfaction and prevalence of sleep disturbances in the general population of Germany: results from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1).

Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):497–502.

Ferri R, Fulda S, Allen RP, Zucconi M, Bruni O, Chokroverty S, et al. World Association of Sleep Medicine (WASM) 2016 standards for recording and scoring leg movements in polysomnograms developed by a joint task force from the International and the European Restless Legs Syndrome Study Groups (IRLSSG and EURLSSG). Sleep Med. 2016;26:86–95.

Park J, Yoo M, Bae SH. Prevalence and predictors of poor sleep quality in K orean older adults. Int J Nurs Pract. 2013;19(2):116–23.

Ghimire S, Baral BK, Karmacharya I, Callahan K, Mishra SR. Life satisfaction among elderly patients in Nepal: associations with nutritional and mental well-being. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):1–10.

Bergmans RS, Zivin K, Mezuk B. Perceived sleep quality, coping behavior, and associations with major depression among older adults. J Health Psychol. 2019;1359105319891650.

Freeman D, Sheaves B, Goodwin GM, Yu L-M, Nickless A, Harrison PJ, et al. The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): a randomised controlled trial with mediation analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(10):749–58.

Berg AI, Hassing LB, McClearn GE, Johansson B. What matters for life satisfaction in the oldest-old? Aging Ment Heal. 2006;10(3):257–64.

Li C, Chi I, Zhang X, Cheng Z, Zhang L, Chen G. Urban and rural factors associated with life satisfaction among older Chinese adults. Aging Ment Health. 2015 Oct;19(10):947–54.

Pinto JM, Fontaine AM, Neri AL. The influence of physical and mental health on life satisfaction is mediated by self-rated health: A study with Brazilian elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;65:104–10.

Rissanen T, Viinamäki H, Honkalampi K, Lehto SM, Hintikka J, Saharinen T, et al. Long term life dissatisfaction and subsequent major depressive disorder and poor mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):1–6.

Yuan Y, Li J, Jing Z, Yu C, Zhao D, Hao W, et al. The role of mental health and physical activity in the association between sleep quality and quality of life among rural elderly in China: A moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. 2020;273:462–7.

Tanaka H, Shirakawa S. Sleep health, lifestyle and mental health in the Japanese elderly: ensuring sleep to promote a healthy brain and mind. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):465–77.

Ballesio A, Lombardo C. Commentary. The Relationship between Sleep Complaints, Depression, and Executive Functions on Older Adults. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1870.

Lin I-F, Wu H-S. Does informal care attenuate the cycle of ADL/IADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life? Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(5):585–94.

Puvill T, Lindenberg J, de Craen AJM, Slaets JPJ, Westendorp RGJ. Impact of physical and mental health on life satisfaction in old age: a population based observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):194.

Siahpush M, Spittal M, Singh GK. Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. Am J Heal Promot. 2008;23(1):18–26.

Dumitrache CG, Rubio L, Rubio-Herrera R. Perceived health status and life satisfaction in old age, and the moderating role of social support. Aging Ment Health. 2017 Jul;21(7):751–7.

Smith J, Borchelt M, Maier H, Jopp D. Health and well–being in the young old and oldest old. J Soc Issues. 2002;58(4):715–32.

Banjare P, Dwivedi R, Pradhan J. Factors associated with the life satisfaction amongst the rural elderly in Odisha, India. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):201.

Allen J. Depression in assisted living. Geriatr Nurs (New York, NY). 2015;36(1):78–80.

Gupta R. The perceived caregiver burden scale for caregivers of elderly people in India. J Appl Gerontol. 2007;26(2):120–38.

Bloom DE, Mahal A, Rosenberg L, Sevilla J. Economic security arrangements in the context of population ageing in India. Int Soc Secur Rev. 2010;63(3-4):59–89.

Bongaarts J, Zimmer Z. Living arrangements of older adults in the developing world: an analysis of demographic and health survey household surveys. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(3):145–57.

Velkoff VA. Living arrangements and well-being of the older population: Future research directions. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population...; 2001.

Khodabakhsh S. Factors Affecting Life Satisfaction of Older Adults in Asia: A Systematic Review. J Happiness Stud. 2022;23(3):1289–304.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334.

Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Gautham MS, Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Kokane A, et al The National Mental Health Survey of India (2016): Prevalence, socio-demographic correlates and treatment gap of mental morbidity. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):361–72.

Chen J, Murayama S, Kamibeppu K. Factors related to well-being among the elderly in urban China focusing on multiple roles. Biosci Trends. 2010;4(2).

Han C-K, Hong S-I. Assets and life satisfaction patterns among Korean older adults: Latent class analysis. Soc Indic Res. 2011;100(2):225–40.

Krause N. Common facets of religion, unique facets of religion, and life satisfaction among older African Americans. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(2):109–17.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

Barslund M, Rand J, Tarp F, Chiconela J. Understanding victimization: the case of Mozambique. World Dev. 2007;35(7):1237–58.

Motivala SJ, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Impairments in health functioning and sleep quality in older adults with a history of depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(8):1184–91.

Chang KJ, Son SJ, Lee Y, Back JH, Lee KS, Lee SJ, et al. Perceived sleep quality is associated with depression in a Korean elderly population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(2):468–73.

Brandolim Becker N, Jesus SN de, Viseu JN, Stobäus CD, Guerreiro M, Domingues RB. Depression and quality of life in older adults: Mediation effect of sleep quality. Int J Clin Heal Psychol. 2018;18(1):8–17.

Nes RB, Czajkowski NO, Røysamb E, Ørstavik RE, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Major depression and life satisfaction: a population-based twin study. J Affect Disord. 2013;144(1–2):51–8.

Otsuka Y, Kaneita Y, Itani O, Nakagome S, Jike M, Ohida T. Relationship between stress coping and sleep disorders among the general Japanese population: a nationwide representative survey. Sleep Med. 2017;37:38–45.

Albert SM, Roth T, Toscani M, Vitiello MV, Zee P. Sleep health and appropriate use of OTC sleep aids in older adults—recommendations of a Gerontological Society of America workgroup. Gerontologist. 2017;57(2):163–70.

Benedict C, Brooks SJ, O’Daly OG, Almen MS, Morell A, Åberg K, et al. Acute sleep deprivation enhances the brain’s response to hedonic food stimuli: an fMRI study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):E443–7.

Chen Q, Hayman LL, Shmerling RH, Bean JF, Leveille SG. Characteristics of chronic pain associated with sleep difficulty in the older population: The MOBILIZE Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1385.

Dykstra PA. Loneliness among the never and formerly married: The importance of supportive friendships and a desire for independence. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(5):321–9.

Yunong H. Family relations and life satisfaction of older people: a comparative study between two different hukous in China. Ageing Soc. 2012;32(1):19–40.

Witter RA, Okun MA, Stock WA, Haring MJ. Education and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1984;6(2):165–73.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A. Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J Public Econ. 2005;89(5–6):997–1019.

Hira TK, Fansiow AM, Titus PM. Changes in financial status influencing level of satisfaction in households. Lifestyles. 1989;10(2):107–21.

Yeo J, Lee YG. Understanding the Association Between Perceived Financial Well-Being and Life Satisfaction Among Older Adults: Does Social Capital Play a Role? J Fam Econ Issues. 2019;40(4):592–608.

Alesina A, Di Tella R, MacCulloch R. Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different? J Public Econ. 2004;88(9–10):2009–42.

Frey BS, Stutzer A. What can economists learn from happiness research? J Econ Lit. 2002;40(2):402–35.

Di Cesare MC, Amori A. Gender and happiness in Italy. In: Population Association of America 2006 Annual Meeting. 2006.

Gerino E, Rollè L, Sechi C, Brustia P. Loneliness, resilience, mental health, and quality of life in old age: A structural equation model. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2003.

Makino K, Ihira H, Mizumoto A, Shimizu K, Ishida T, Furuna T. Associations between the settings of exercise habits and health-related outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(7):2207–11.

Chokkanathan S, Mohanty J. Health, family strains, dependency, and life satisfaction of older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;71:129–35.

Bincy K, Logaraj M, Ramraj B. Depression and its associated factors among the older adults in rural, Tamilnadu, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2021;10:100677.

Fernández-Niño JA, Bonilla-Tinoco LJ, Manrique-Espinoza BS, Romero-Martínez M, Sosa-Ortiz AL. Work status, retirement, and depression in older adults: An analysis of six countries based on the Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). SSM - Popul Heal. 2018;6:1–8.

Burgard SA, Elliott MR, Zivin K, House JS. Working conditions and depressive symptoms: a prospective study of US adults. J Occup Environ Med Coll Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(9):1007.

Roy K, Chaudhuri A. Influence of socioeconomic status, wealth and financial empowerment on gender differences in health and healthcare utilization in later life: evidence from India. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(9):1951–62.

Quisumbing AR. Household decisions, gender, and development: a synthesis of recent research. International Food Policy Research Institute; 2003.

Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR, Huba GJ. Depression and physical illness: A multiwave, nonrecursive causal model. J Health Soc Behav. 1984;350–71.

Bisschop MI, Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, Beekman ATF, van Tilburg W. The longitudinal relation between chronic diseases and depression in older persons in the community: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(2):187–94.

Ansari S, Anand A, Hossain B. Multimorbidity and depression among older adults in India: Mediating role of functional and behavioural health. PLoS One. 2022 Jun;17(6):e0269646.

Kwok SYCL, Yeung DYL, Chung A. The Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support on the Relationship between Physical Functional Impairment and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Nursing Home Elderly in Hong Kong. Weisz J, editor. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:469895.

Chou K, Chi I. Combined effect of vision and hearing impairment on depression in elderly Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(9):825–32.

Smith KJ, Victor C. Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing Soc. 2019;39(8):1709–30.

Agrawal S. Effect of living arrangement on the health status of elderly in India: Findings from a national cross sectional survey. Asian Popul Stud. 2012;8(1):87–101.

Yeunhee K, Chung H, Yoonjung KIM. Differences in Health-related Quality of Life and Mental Health by Living Arrangement among Korean Elderly in the KNHANES 2010–2012. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(11):1512.

Stek ML, Vinkers DJ, Gussekloo J, Beekman ATF, Van Der Mast RC, Westendorp RGJ. Is depression in old age fatal only when people feel lonely? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):178–80.

Bandita, Boro Shobhit, Srivastava Nandita, Saikia Is There an Association Between Change in Old-Age Living Arrangements and Older Adults’ Psychological Health and Subjective Well-Being in India? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study. Ageing International 10.1007/s12126-021-09470-6

IIPS. Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017–18, India Report, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. Mumbai; 2020. url: https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_India_Report_2020_compressed.pdf (accessed 15.07.2022; 18.50 IST)

Shreya, Banerjee Indrani, Roy Chowdhury Hafiz T.A., Khan (2020) Inequities in curative health-care utilization among the adult population (20–59 years) in India: A comparative analysis of NSS 71st (2014) and 75th (2017–18) rounds. PLOS ONE 15(11) e0241994-10.1371/journal.pone.0241994 10.1371/journal.pone.0241994

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Bandita Boro and Shreya Banerjee; Data curation: Shreya Banerjee and Bandita Boro; Methodology: Shreya Banerjee; Formal analysis and investigation: Shreya Banerjee; Writing-original draft: Bandita Boro; Writing- review and editing: Shreya Banerjee and Bandita Boro. Both the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used the LASI Wave-1, a secondary source of data available in the public domain for use by researchers hence no separate ethical clearance was required for this study. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) extended the necessary guidelines and ethics approval for undertaking the LASI survey. Since the authors did not collect primary data, ‘written informed consent from participants’ is not applicable.

All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Banerjee, S., Boro, B. Analysing the role of sleep quality, functional limitation and depressive symptoms in determining life satisfaction among the older Population in India: a moderated mediation approach. BMC Public Health 22, 1933 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14329-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14329-9