Abstract

Background

Arterial hypertension (aHT) is the leading cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor in sub-Saharan Africa; it remains, however, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Community-based care services could potentially expand access to aHT diagnosis and treatment in underserved communities. In this scoping review, we catalogued, described, and appraised community-based care models for aHT in sub-Saharan Africa, considering their acceptability, engagement in care and clinical outcomes. Additionally, we developed a framework to design and describe service delivery models for long-term aHT care.

Methods

We searched relevant references in Embase Elsevier, MEDLINE Ovid, CINAHL EBSCOhost and Scopus. Included studies described models where substantial care occurred outside a formal health facility and reported on acceptability, blood pressure (BP) control, engagement in care, or end-organ damage. We summarized the interventions’ characteristics, effectiveness, and evaluated the quality of included studies. Considering the common integrating elements of aHT care services, we conceptualized a general framework to guide the design of service models for aHT.

Results

We identified 18,695 records, screened 4,954 and included twelve studies. Four types of aHT care models were identified: services provided at community pharmacies, out-of-facility, household services, and aHT treatment groups. Two studies reported on acceptability, eleven on BP control, ten on engagement in care and one on end-organ damage. Most studies reported significant reductions in BP values and improved access to comprehensive CVDs services through task-sharing. Major reported shortcomings included high attrition rates and their nature as parallel, non-integrated models of care. The overall quality of the studies was low, with high risk of bias, and most of the studies did not include comparisons with routine facility-based care.

Conclusions

The overall quality of available evidence on community-based aHT care is low. Published models of care are very heterogeneous and available evidence is insufficient to recommend or refute further scale up in sub-Sahara Africa. We propose that future projects and studies implementing and assessing community-based models for aHT care are designed and described according to six building blocks: providers, target groups, components, location, time of service delivery, and their use of information systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and aim

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines aHT as a persistent systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg. An estimated 1.28 billion adults aged 30–79 years worldwide have aHT, two-thirds of them living in low- and middle-income countries. Modifiable risk factors include unhealthy diets (excessive salt consumption, saturated fat and trans fats, low intake of fruits and vegetables), physical inactivity, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, and overweight or obesity. Non-modifiable risk factors include a family history of aHT, age over 65 years, and co-existing diseases such as diabetes or kidney disease. aHT is the largest modifiable cardiovascular risk factor (CVRF) globally and the leading cause of the 22.9 million deaths attributed to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) each year in sub-Saharan Africa [1,2,3].

Prevalence of aHT is highest in the African region, where an estimated 27% of the population aged 30–79 years have aHT [4]. However, despite an increasing burden of CVDs, aHT awareness, diagnosis, treatment and control remain low [5,6,7,8]. Barriers to aHT control exist at patient and health system levels [9, 10]. Major challenges for people living with aHT relate to the asymptomatic nature of the condition, leading to a delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation. Once diagnosed, aHT requires lifelong lifestyle modifications, frequent medical check-ups, ongoing counselling and regular adaptation of treatment dosage or drug regimen [9, 11]. Regional health systems remain poorly adapted to provide comprehensive CVD care, with insufficiently trained, equipped and supported workforce, limited availability of treatment options, and infrequent or non-existing monitoring of treatment outcomes, such as BP control and end-organ function [8, 12].

As aHT is a prevalent, chronic and, often, asymptomatic health condition, successful care models must be easy to access and provide long-term medical follow-up [13,14,15,16]. Community-based health services have been proposed as solutions to bridge existing barriers in access and to scale up services for aHT [17,18,19]. These care models frequently promote task-shifting/sharing, simplification of clinical care algorithms and integration of other services [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Although the terms task shifting and task sharing are sometimes used interchangeably, task shifting is defined as a systematic and planned transfer of care duties from physicians to non-physicians, such as nurses, or community health workers [26], whereas task sharing describes professionals working together to deliver health services. In practice, this implies that when physicians are not available, care tasks must be shifted to non-physician workers for the health system to function. When a few physicians are available, tasks may be shared with other health-care professionals with some supervision or referral to physicians [27, 28].

To date, community-based and out-of-facility care models have been applied to scale up treatment for HIV and tuberculosis (TB), with different success [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. However, currently, there is no consensus nor guidance on how such models should be structured to have substantial impact in aHT care. Similarly, evidence to understand how, and to what extent tasks could be shifted to lower cadre health care providers, and how services could be decentralized is lacking. A preliminary search of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Evidence Synthesis revealed no systematic reviews or similar scoping reviews on this topic. To inform future research, public health programs, and policies, this literature scoping review aims to catalogue the existing community-based aHT care models for non-pregnant adults in sub-Sahara Africa.

Methods

We chose a scoping review methodology to provide an overview and a categorization of existing knowledge, rather than a narrow synthesis of a predefined research question. Typically, scoping reviews are used to map the key concepts that underpin a field of research, as well as to clarify working definitions, and/or the conceptual boundaries of a topic. In this scoping review, the authors explore the breadth of the literature, map and summarize the evidence, and inform future research in the topic [36]. We followed the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [37], further developed by Levac et al. [38] and the Joanna Briggs Institute [39]. The protocol has been published [40]. Our primary objective is to construct a framework to categorize these aHT care models. Secondary objectives include: 1) to appraise the models of care, in terms of acceptability, BP control, engagement in care, and occurrence of end-organ damage, 2) to describe within-study comparisons between community-based and facility-based models of care, if provided by authors and 3) to identify gaps in the literature with respect to community-based service models for aHT.

We included studies in which participants were non-pregnant adults ≥ 18 years, diagnosed with aHT and living in sub-Saharan Africa. A summary of eligibility criteria is available in Table 1. Included studies had to report medical management and treatment for aHT that differed from conventional facility-based care in terms of provider cadre, location, or frequency of follow-up visits. Interventions had to address general management and medical treatment for aHT, including lifestyle modification, self-care, treatment administration and screening or management of organ complications. Included studies had also to report on at least one of the following outcomes: acceptability of the care model, BP control, engagement in care, or end-organ damage. We did not include studies where only aHT screening or diagnosis was reported. Studies where the intervention was a mere add-on and did not replace, at least partly, facility-based care, or did not reduce the frequency of visits to a professional health care worker, were not eligible. We also excluded studies that reported the pilot experience of a published intervention, if the model of care was the same.

A first literature search was conducted on 23 May 2021. The search was repeated on 15 October 2021, yielding no further eligible studies. The literature search strategy was drafted and refined through discussions with the study team and an experienced scientific information specialist (JH), then reviewed by a second information specialist (CA). The search strategy was first developed in Embase Elsevier [41], and subsequently translated for the databases Medline Ovid [42], Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) [43], and Scopus [44]. Detailed information on the search strategy and is available in Annex 1.

No language limits or date restrictions were applied. Conference abstracts where no peer-reviewed publication was available were excluded. The search results from each database were imported to EndNote X9 and deduplicated according to the method of Bramer [45]. Two independent reviewers (LG, ER) individually assessed study titles, abstracts, and full texts against the predefined eligibility criteria of the review. Authors were contacted when the description of the model of care was unclear or incomplete to decide on inclusion or exclusion. Backward and forward citation from included studies was used to identify additional articles that met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussions between the two first authors (LGF, EF) and the last author (NDL).

Data extraction was independently conducted by two authors (LG, ER) using a tool created in Word™v.16.0 and piloted on three studies. Information included author, year of publication, study design, target population, location of study, duration of follow-up, type of community-care model, health provider cadre, outcomes measured and comparison arm if available. All reported variables were described as the authors defined them, with no other assumptions. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed and solved by consensus. The information was chartered in Excel™ v16.0.

We summarized each study’s outcomes and, where possible, we pooled outcomes and reported average, range and/or median values. If models of care were similar, we grouped results by intervention type and reported common features, such as health cadre providing the service, location of delivery and frequency, use of e-Health, or integration with other chronic conditions. Assessment of quality of the included evidence was not initially planned, and thus not specified in the published protocol. However, we undertook the analysis at a later stage to comment on recommendations for evidence generation in the field. We assessed the quality of the included cohort and case–control studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [46]. The domains of the tool rate the selection of participants, comparability, and outcomes, to a maximum of 9 points. Whereas this scale is widely used to assess the quality of observational studies, there are no established thresholds to define “poor” or “good" quality of a study. Based on a recent literature review, we applied a threshold ≥ 6 as “no high risk of bias” [47]. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were judged using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool to assess RCTs [48] and cluster RCTs [49]. We evaluated the sequence generation, participant recruitment with respect to randomization timing, deviation from intended intervention, completeness of outcome data for the main outcome, bias in the measurement of outcome, and bias in the selection of the reported result. Additionally, we addressed both quantitative and qualitative gaps in the literature and proposed suggestions for further studies and applications for programmatic scale up. The results of the review are documented in accordance with the PRISMA-P reporting checklist [50].

Using the reported experiences, we conceptualized a framework containing six building blocks to design and describe community care models for aHT.

Results

Search results

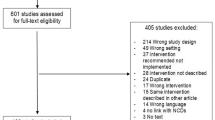

Literature search and deduplication yielded a total of 4,618 citations (Prisma Fig. 1). Titles and abstracts screening resulted in a first classification, after which 76 papers were included for full-text review. Reasons for exclusion at full-text screening included: studies described models with most of the aHT care happening at facility level (n = 6); the description of the model of care lacked details on the content of the intervention (n = 4); studies piloted a model of care that was further described in an included study (n = 4); and the described model of care or outcomes did not match the inclusion criteria (n = 53). Backward and forward citation searching of included studies yielded 333 additional references; all of them were screened, and three new studies were identified. As a result, 12 references were finally included [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62].

Studies selection PRISMA diagram. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71, For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Characteristics of the studies

Characteristics of included studies are available in Table 2. Identified studies were published between 1994 and 2021, and seven (58%) were published after 2017 [52,53,54,55,56,57, 59, 61] (Fig. 2). Eleven (92%) were single country studies [51,52,53,54,55,56, 58,59,60,61,62] whereas one [57] implemented the same service model in two countries. West African populations were represented in four (33%) [52, 55, 59, 60], East African populations in five (42%) [53, 54, 56, 58, 61], Southern African populations in two (17%) [51, 62] studies and one (8%) study presented results from both East and West Africa [57] (Fig. 3). Seven (58%) studies were conducted in urban areas [51, 54, 55, 58,59,60,61], three (25%) in rural areas [53, 56, 62], one (8%) study [52] took place in semi-urban areas and one (8%) [57] study reported findings in urban and rural settings. No studies reported interventions in special settings, such as remote, hard-to-reach populations or conflict areas.

The majority were before-after studies, describing post-intervention outcomes [52,53,54, 57, 58, 60, 62] (7, 58%). Other designs included: case-control [51] (1, 8%), mixed-methods [61] (1, 8%), prospective non-randomized controlled trial [55] (1, 8%), RCT [59] (1, 8%), and cluster RCT [56] (1, 8%). The primary aim of most of the studies was to test a specific intervention adapted to a particular context [51, 55,56,57, 59,60,61,62] (8, 67%), while, four (33%) studies were part of broader health or non-communicable chronic disease (NCD) implementation projects [52,53,54, 58]. Sample size varied from 42 to 7188 participants, with five (42%) studies including more than 1000 participants [52, 56,57,58, 62]. The majority of the studies (10, 83%), narrowed the inclusion criteria to participants with uncomplicated aHT [52,53,54,55,56, 58,59,60,61,62]. A total of seven (58%) studies had no comparator arm [52,53,54, 57, 58, 60, 61], whereas five (42%) provided intra-study comparisons of interventions [51, 55, 56, 59, 62], with either standard of care [51, 55, 59] or a second intervention [56, 62].

Models of care

Four different service delivery models were described: services provided by community pharmacists [52, 55, 60, 61], temporary or permanent stations placed at strategic and accessible locations in the community [54, 62], routine facility-based care complemented with home visits or services in other community locations to reduce patient visits to the facility [51, 57, 59], and care provided at the time of collecting medication in aHT treatment groups [53, 56, 58]. All models applied different elements of task shifting or task sharing. Medical specialists, including cardiologists or general doctors, had a substantial role in supporting the services in seven (58%) studies, either managing referred patients or supporting the practice of lower cadres [51, 52, 54, 56, 57, 61, 62]. Among non-physician delivered services, aHT care was delivered by nurses [51, 52, 54, 56,57,58,59, 62] (8, 67%), community health workers [51,52,53,54, 56, 57] (CHW) (6, 50%) or pharmacists [51, 52, 55, 56, 60, 61] (5, 42%). For each model of care, authors described the preparation and training given to the health workers involved. Most commonly, an initial training session included training on BP measurement technique, healthy lifestyle, clinical guidelines, counselling and support techniques, and familiarization with the information capturing tools. Sessions were longer for lay cadres and shorter for health professionals and only three (25%) provided ongoing mentoring or supervision [57, 59, 60].

Five (42%) studies specifically reported on aHT medical treatment regimens [52, 56, 57, 60, 62] (Table 3). Treatment choices reflected historical and context recommendations, as well as, availability of drugs. Most frequently, treatment algorithms used diuretics, calcium channel blockers (CCB), ß-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Treatments included the use of monotherapy and combinations, however, none used fixed dose combinations.

Seven (58%) studies integrated aHT care with other prevalent chronic health conditions, mostly diabetes [51, 53, 55, 56, 58], and HIV [58]. Only two (16%) models integrated care with other NCDs, such as mental health, epilepsy, asthma, or heart disease [53, 59]. Five (42%) studies used electronic information systems as a substantial component of the model of care, including clinical and computerized decision support systems or e-health platforms [52, 55, 57, 60, 61].

Measured outcomes

Table 4 summarizes the studies’ outcomes of interest, perceived benefits, and challenges of the models of care, as described by the authors. Two (17%) studies reported on acceptability of the care model [60, 61]; eleven (92%) on BP control [51,52,53, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]; and 10 (83%) on engagement in care [52,53,54,55,56, 58,59,60,61,62]. Only one (8%) study reported on end-organ damage. Nine (75%) studies report outcomes between an average follow up of 6–12 months [51, 52, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61], while 3 (25%) studies reported a follow up longer than one year [53, 54, 57].

Acceptability was reported either collecting the experience of the health workers [61], or measuring patients’ satisfaction through qualitative research and the Larson satisfaction questionnaire [63]. Of the two studies reporting satisfaction, one model delivered home-based aHT treatment and one provided care in community pharmacies [60, 61]. Participants reported benefits in adhering to the treatment and general knowledge on self-care practices.

With regards to reporting BP control, targets for (SBP, (DBP and aHT definitions varied, reflecting historical definitions [62] or pragmatic targets linked to inclusion criteria in the care model [53, 58]. Seven (58%) studies [52, 55,56,57, 59,60,61] used SBP ≤ 140 mmHg and DBP ≤ 90 mmHg to define BP control, while two (16%) [55, 61] modified control thresholds for diabetic patients. Eight (67%) studies showed a significant improvement in BP control [51, 52, 55, 57, 58, 60,61,62] and one (8%) showed that BP was controlled in higher proportion for diabetic patients receiving community-based services [51].

Eight (67%) studies reported engagement in care [51, 52, 54,55,56, 58, 59, 61] using different measures: lost to follow-up or death [54, 58], self-reported adherence to the treatment [54, 55, 59,60,61], regular use of the e-health support platform [61] or attendance to follow up visits [51, 52, 56, 58]. Two (16%) community pharmacy models in West Africa were the only ones that reported significant improvements in engagement in care and adherence to aHT treatment [55, 59], whereas two studies suggest that community care posts and home-based care could increase long-term engagement in aHT care [52, 54].

The only study reporting end-organ damage measured serum creatinine as surrogate marker for renal function. In this care model, laboratory tests were offered at the time of patients group meetings and collection of aHT medication in a subset of participants [58].

Authors reported the perceived benefits of the aHT models of care in relation to the health system and the users. Benefits for the health system included: task-sharing across different professionals, decrease in daily patients load at facilities, and possibility to offer wider access for services and prevention of other CVDs [51, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Perceived advantages from the patients’ perspective referred to increased flexibility to access services, and reduction of costs and waiting times [51, 53,54,55, 57, 58, 61]. One study noted positive impacts in patients’ quality of life, as the model of care addressed broader social determinants of health closely linked to CVDs, such as poverty, rather than just providing aHT treatment [56].

Authors also reported the weaknesses of these aHT care models. Doubts on generalizability of the models arose in relation to strict inclusion criteria, as care was provided either to selected groups or clinically stable participants. Seven (7, 58%) used clinically narrow eligibility criteria, excluding patients with complicated aHT, severe conditions, or comorbidities [53, 54, 56,57,58, 61]. One study in South Africa provided care only to the privileged white population during Apartheid [62]. High attrition rates through lost to follow-up and mortality, deficiencies in data quality, small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, or lack of control arms compromised the report of accurate outcomes and the capacity to provide a more complete picture of the real benefit of these models [52,53,54,55, 57, 59, 60, 62]. Poor sustainability of care models was brought up in relation to the use of vertical, non-integrated interventions, including parallel remuneration of health workers, lack of staff, medication stock outs or difficulties in managing and sustaining eHealth solutions [51,52,53, 55, 60, 61]. The overall quality of provided services was a common concern to authors, including difficulties in providing ongoing supervision and mentoring of lower cadres [51,52,53,54,55]. Specifically, the models testing services at community pharmacies in West Africa expressed concerns about the capacity to contribute to a substantial change in service delivery, as the strategy was too far away from existing policies and standards, and sustainability was heavily associated with motivation and remuneration of professionals [55, 60].

Quality of evidence

Nine cohort studies and one case control study were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [64,65,66] (Table 5). All studies scored below 6, mainly driven by very narrowly selected study populations and the absence of comparators in many of the studies. One RCT and one cluster-RCT were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs [48, 49] (Table 6). Overall bias assessment was “low risk for bias” for one study and “some concerns” for the other.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this scoping review is the first comprehensive analysis of community-based aHT treatment models in sub-Saharan Africa. We systematically compiled and synthesized the current evidence related to service delivery models for aHT treatment that differ from traditional, facility-based care between 1993 and 2021. The increasing number of publications in recent years indicates that this is an active field where rapid developments can be expected in future [67,68,69,70,71]. We identified 12 studies that described one or more outcomes of interest from four distinct types of community-based aHT service delivery in five countries. However, only a minority of studies (4, 33%) compared alternative models to conventional care or to other interventions, making it difficult to draw solid conclusions about the overall effectiveness of these models on clinical outcomes. Due to the wide heterogeneity of the models of care, inclusion criteria, outcome definitions, participants follow up and study types we only described each of the studies individually, rather than providing aggregated statistics.

In the process of summarizing the literature for this scoping review, we abstracted the main elements that integrate the models of care, as described by the authors (manuscript tables). These elements constitute the “building blocks” of each care model and are represented in Fig. 4: cadre of health care provider (who delivers the service, including self-care), target population (for whom the care model is created), location of service delivery (where is the service provided), components of the service package, information systems (methods used for collecting information about the users and the service), and the timing of service delivery (when is the service available to the user). Each of these elements is intrinsically composed by other components. i.e.: in the “information systems” category, different models use either paper-based/digitalized patients’ files/cards and/or digital technology. We propose the use of these building blocks to either design or analyze care models for aHT and in general CVDs. To tailor a model of care to a given setting, each of the six blocks should be taken into account and adapted, considering different aspects, such as: setting, resources, cultural preferences, or specific needs of the target population (Fig. 4). Similar models have been used to scale up tuberculosis or HIV services [29, 72,73,74,75,76].

The West African experiences mostly integrated pharmacists and microfinance solutions in urban areas, while East and Southern African models tested interventions that increased access to care in rural communities. In all service models, care is most often provided by lower cadres of health workers, decreasing frequency of interactions with routine services, and combining a high level of self-care. However, most of the models only included participants with already an acceptable BP control, had a short follow-up period, and failed to provide comparable performance with facility-based care in the same setting. Although it is hard to evaluate their real impact, the reported care models do not seem to be associated with lower user’s satisfaction or worse treatment outcomes.

Beyond clinical indicators that report individual aHT treatment outcomes for participants receiving care in these models, a few studies collected patients’ and service providers’ perspectives. Future studies should seek a combination of quantitative and qualitative data and possibly socio-economic data to understand the real reach and impact of such models. The use of electronic information systems becomes an important part of the care in the most recent studies. Patients receive reminders for adherence to medication, general lifestyle counseling or provision of personalized risk-based care plans through, phone calls, SMS, or use of other e-Health platforms. Similarly, these systems support communication between medical specialists, nurses and lay workers [52, 53, 55, 56, 60, 61].

One interesting finding of this review reinforces the idea that expanding the provision of chronic aHT care, and probably other chronic health conditions, to health workers and structures that are outside of traditional care in facilities, reduces, but does not eliminate the need of care provided by medical doctors or specialized nurses. Rather, these services can be used to provide referral paths to manage patients that need to be evaluated for more complex comorbidities or new cardiovascular events by specialised health workers. Our findings describe diverse and heterogenous models of care and suggest that each setting requires its own specifically adapted model of care, taking into account the six building blocks after careful analysis of local gaps and needs. As such, there is not just “one size fits all” care model to efficiently expand out-of-clinic aHT management.

In an effort to close the global aHT treatment gap and improve BP control at societal level, in 2021 the WHO issued updated guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of aHT in non-pregnant adults [3]. These new global recommendations guide decisions such as the threshold for the initiation of pharmacological aHT treatment, choice of treatment regimens and drug combinations, frequency of patients follow up, BP control targets, and the cadre of providers who may initiate or manage long-term treatment. However, regarding frequency of patients’ follow up and treatment by nonphysician professionals these recommendations remain conditional due to low-certainty evidence. Through scoping the published literature on this topic, we have identified additional research questions where future research could help establishing evidence-based recommendations to scale up similar aHT models of care. First, the development of standard descriptions of the models of care, taking into account the six building blocks, definitions of inclusion criteria of participants and clinical outcomes will be needed. Second, as aHT is a chronic condition, it will be important to understand the use of these models to achieve and maintain BP control beyond the first 12 or 24 months of enrolment, and even longer follow up. Third, to understand the potential of these models to improve BP control at population level, it will be important to describe the patterns of transition between conventional aHT care and one or subsequent alternative models across years of care. Fourth, investigators could provide a description of the capacity that each model of care has to reach BP targets after a period of uncontrolled BP and to integrate care for important co-morbidities, like diabetes, HIV, or tuberculosis. Fifth, reports should aim to demonstrate a decrease of overall risk in CVD events and aHT-related end-organ damage. Sixth, studies should also include a description of the wider hypertensive population, not included in these models, including their treatment outcomes for reference comparison. Lastly, the reporting of costs and cost-effectiveness will be crucial to mobilize investments that can catalyse a significant scale up of these services.

Strengths and limitations

Our review provides a comprehensive description and evaluation of the published community-based aHT care models, following a structured methodological framework. Equally, this review has several limitations. The concept of non-traditional, outside-of-facility health service is heterogenous, poorly defined and lacks standard terminology. Our search terms included most common related synonyms, however, despite the efforts to develop a broad literature search strategy following PRISMA guidance, the selection of standard search terms and databases may have excluded some relevant publications. Our search also excluded regional databases and grey literature; therefore, it is possible that we have missed evidence provided by interventions used in practice and not published. Lastly, we could have missed relevant data when the authors failed to provide sufficient details or disaggregated results [69, 77,78,79,80].

Conclusions

The search for efficient and sustainable service delivery models for the management of aHT in sub-Saharan settings, outside of conventional care, is a rapid evolving field. This scoping review has identified different community-based models that can potentially be seeds of scalable programs that integrate comprehensive chronic care.

However, the wide heterogeneity of the studies, lack of standardization of definitions and measurement of outcomes, small number of participants, short follow up, and lack of reliable comparisons with standard of care, does not allow to describe their real impact in achieving long-term BP control and overall CVD risk decrease. The available literature does not provide a sound basis for policymakers and implementers on whether, and in what form, community-based care delivery models for aHT could be applied to counteract the growing CVD burden in sub-Saharan Africa. We propose that future projects and studies implementing and assessing community-based models of aHT care are designed and described according to six building blocks defining the providers, target groups, components, location, time of services and their use of information systems.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. All articles used for the review are in the references section.

Change history

05 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13988-y

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme

- aHT:

-

Arterial Hypertension

- ARBs:

-

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

- BP:

-

Blood Pressure

- CCB:

-

Calcium channel blockers

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular Diseases

- CHW:

-

Community Health Worker

- DBP:

-

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- NCDs:

-

Non-Communicable Diseases

- RCTs:

-

Randomized Controlled Trials

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pressure

References

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-Based Studies From 90 Countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912.

Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1375–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2.

World Health Organization. Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Hypertension in Adults. World Health Organization; 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344424 Accessed 25 Oct 2021.

Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. The Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1.

High Blood Pressure in Sub‐Saharan Africa: The Urgent Imperative for Prevention and Control. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12620

Ataklte F, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Taye B, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Kengne AP. Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):291–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04394.

Schutte AE. Urgency for South Africa to prioritise cardiovascular disease management. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(2):e177–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30476-5.

Yuyun MF, Sliwa K, Kengne AP, Mocumbi AO, Bukhman G. Cardiovascular Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa Compared to High-Income Countries: An Epidemiological Perspective. Glob Heart. 2020;15(1):15. https://doi.org/10.5334/gh.403.

Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(4):223–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2.

Khatib R, Schwalm JD, Yusuf S, et al. Patient and healthcare provider barriers to hypertension awareness, treatment and follow up: a systematic review and meta-analysis of qualitative and quantitative studies. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e84238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084238.

ESC/ESH Guidelines on Arterial Hypertension (Management of). https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Arterial-Hypertension-Management-of, https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Arterial-Hypertension-Management-of Accessed 17 Sept 2021.

Azevedo MJ. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. Historical Perspectives on the State of Health and Health Systems in Africa, Volume II. Published online February 3, 2017:1–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32564-4_1

Vedanthan R, Kamano JH, Bloomfield GS, Manji I, Pastakia S, Kimaiyo SN. Engaging the Entire Care Cascade in Western Kenya: A Model to Achieve the Cardiovascular Disease Secondary Prevention Roadmap Goals. Glob Heart. 2015;10(4):313–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2015.09.003.

Jardim TV, Reiger S, Abrahams-Gessel S, et al. Disparities in Management of Cardiovascular Disease in Rural South Africa. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(11):e004094. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004094.

Musinguzi G, Bastiaens H, Wanyenze RK, Mukose A, Geertruyden JPV, Nuwaha F. Capacity of Health Facilities to Manage Hypertension in Mukono and Buikwe Districts in Uganda: Challenges and Recommendations. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11): e0142312. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142312.

Matheson GO, Pacione C, Shultz RK, Klügl M. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):472–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.014.

Ciccacci F, Orlando S, Majid N, Marazzi C. Epidemiological transition and double burden of diseases in low-income countries: the case of Mozambique. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:49. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2020.37.49.23310.

Stower H. A disease transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1647–1647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0659-0.

Kabudula CW, Houle B, Collinson MA, et al. Progression of the epidemiological transition in a rural South African setting: findings from population surveillance in Agincourt, 1993–2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):424. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4312-x.

Jongen VW, Lalla-Edward ST, Vos AG, et al. Hypertension in a rural community in South Africa: what they know, what they think they know and what they recommend. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6642-3.

Jeet G, Thakur JS, Prinja S, Singh M. Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: Evidence and implications. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0180640. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180640.

Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182354.

Martinez J, Ro M, Villa NW, Powell W, Knickman JR. Transforming the delivery of care in the post-health reform era: what role will community health workers play? Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):e1-5. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300335.

Dzudie A, Kingue S, Dzudie A, et al. Roadmap to achieve 25% hypertension control in Africa by 2025. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2017;28(4):261–72. https://doi.org/10.5830/CVJA-2017-040.

Twagirumukiza M, Van Bortel LM. Management of hypertension at the community level in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): towards a rational use of available resources. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25(1):47–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2010.32.

Task Shifting - Global Recommendations and Guidelines. :92. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43821/9789?sequence=1.

Orkin AM, Rao S, Venugopal J, et al. Conceptual framework for task shifting and task sharing: an international Delphi study. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00605-z.

Anand TN, Joseph LM, Geetha AV, Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P. Task sharing with non-physician health-care workers for management of blood pressure in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e761–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30077-4.

Huber A, Pascoe S, Nichols B, et al. Differentiated Service Delivery Models for HIV Treatment in Malawi, South Africa, and Zambia: A Landscape Analysis. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2021;9(2):296–307. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00532.

Long L, Kuchukhidze S, Pascoe S, et al. Retention in care and viral suppression in differentiated service delivery models for HIV treatment delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a rapid systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(11):e25640. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25640.

Daru P, Matji R, AlMossawi HJ, Chakraborty K, Kak N. Decentralized, Community-Based Treatment for Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Bangladesh Program Experience. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2018;6(3):594–602. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00345.

Leavitt SV, Jacobson KR, Ragan EJ, et al. Decentralized Care for Rifampin-Resistant Tuberculosis, Western Cape South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(3):728–39. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2703.203204.

Loveday M, Wallengren K, Brust J, et al. Community-based care vs. centralised hospitalisation for MDR-TB patients, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(2):163–71. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.14.0369.

Sinanovic E, Floyd K, Dudley L, Azevedo V, Grant R, Maher D. Cost and cost-effectiveness of community-based care for tuberculosis in Cape Town, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7(9 Suppl 1):S56-62.

Amstutz A, Lejone TI, Khesa L, et al. Offering ART refill through community health workers versus clinic-based follow-up after home-based same-day ART initiation in rural Lesotho: The VIBRA cluster-randomized clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18(10): e1003839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003839.

11.1.1 Why a scoping review? - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/3283910906/11.1.1+Why+a+scoping+review%3F Accessed 10 Apr 2022.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 2010;5(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

González Fernández L, Firima E, Huber J, et al. Community-based care models for arterial hypertension management in non-pregnant adults in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review protocol. F1000Res. 2021;10:487. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.51929.1.

Elsevier. Discover - Embase | Elsevier Solutions. Elsevier.com. https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/15578/c/10547/supporthub/embase/) Accessed 26 Jul 2021.

Ovid MEDLINE®. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/901 Accessed 26 Jul 2021.

CINAHL Database | EBSCO. https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/cinahl-database Accessed 26 Jul 2021.

Scopus preview - Scopus - Welcome to Scopus. https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus/how-scopus-works/content?dgcid=RN_AGCM_Sourced_300005030Accessed 26 Jul 2021.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–3. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014.

Lo CKL, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-45.

Luchini C, Veronese N, Nottegar A, et al. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-research: Review/guidelines on the most important quality assessment tools. Pharm Stat. 2021;20(1):185–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.2068.

Risk of bias tools - RoB 2 tool. https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/rob-2-0-tool Accessed 17 Oct 2021.

Risk of bias tools - RoB 2 for cluster-randomized trials. https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/rob-2-for-cluster-randomized-trials Accessed 17 Oct 2021.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Ndou T, van Zyl G, Hlahane S, Goudge J. A rapid assessment of a community health worker pilot programme to improve the management of hypertension and diabetes in Emfuleni sub-district of Gauteng Province, South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):19228. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.19228.

Adler AJ, Laar A, Prieto-Merino D, et al. Can a nurse-led community-based model of hypertension care improve hypertension control in Ghana? Results from the ComHIP cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e026799. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026799.

Stephens JH, Addepalli A, Chaudhuri S, Niyonzima A, Musominali S, Uwamungu JC, Paccione GA. Chronic Disease in the Community (CDCom) Program: Hypertension and non-communicable disease care by village health workers in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247464. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247464.

Kuria N, Reid A, Owiti P, et al. Compliance with follow-up and adherence to medication in hypertensive patients in an urban informal settlement in Kenya: comparison of three models of care. Trop Med Int Health. 2018;23(7):785–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13078.

Marfo AFA, Owusu-Daaku FT. Exploring the extended role of the community pharmacist in improving blood pressure control among hypertensive patients in a developing setting. J of Pharm Policy and Pract. 2017;10(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-017-0127-5.

Vedanthan R, Kamano JH, Chrysanthopoulou SA, et al. Group Medical Visit and Microfinance Intervention for Patients With Diabetes or Hypertension in Kenya. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(16):2007–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.03.002.

Otieno HA, Miezah C, Yonga G, et al. Improved blood pressure control via a novel chronic disease management model of care in sub-Saharan Africa: Real-world program implementation results. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23(4):785–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14174.

Khabala KB, Edwards JK, Baruani B, et al. Medication Adherence Clubs: a potential solution to managing large numbers of stable patients with multiple chronic diseases in informal settlements. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(10):1265–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12539.

Bolarinwa OA, Juni MH, Nor Afiah MZ, Salmiah MS, Akande TM. Mid-term impact of home-based follow-up care on health-related quality of life of hypertensive patients at a teaching hospital in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22(1):69–78. https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_246_17.

Oparah AC, Adje DU, Enato EFO. Outcomes of pharmaceutical care intervention to hypertensive patients in a Nigerian community pharmacy. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;14(2):115–22. https://doi.org/10.1211/ijpp.14.2.0005.

Nelissen HE, Cremers AL, Okwor TJ, et al. Pharmacy-based hypertension care employing mHealth in Lagos, Nigeria – a mixed methods feasibility study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):934. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3740-3.

Steyn K, Rossouw JE, Jooste PL, et al. The intervention effects of a community-based hypertension control programme in two rural South African towns: the CORIS Study. S Afr Med J. 1993;83(12):885–91.

Larson LN, Rovers JP, MacKeigan LD. Patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care: update of a validated instrument. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(1):44–50. https://doi.org/10.1331/108658002763538062.

nosgen.pdf. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf Accessed 17 Oct 2021.

Abesig J, Chen Y, Wang H, Sompo FM, Wu IXY. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies. Published online June 12, 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234348.s002

Luchini C, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World Journal of Meta-Analysis. 2017;5(4):80–4. https://doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v5.i4.80.

Lygidakis C, Uwizihiwe JP, Kallestrup P, Bia M, Condo J, Vögele C. Community- and mHealth-based integrated management of diabetes in primary healthcare in Rwanda (D2Rwanda): the protocol of a mixed-methods study including a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7): e028427. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028427.

Lumu W, Kibirige D, Wesonga R, Bahendeka S. Effect of a nurse-led lifestyle choice and coaching intervention on systolic blood pressure among type 2 diabetic patients with a high atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk: study protocol for a cluster-randomized trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05085-z.

Muhihi AJ, Urassa DP, Mpembeni RNM, et al. Effect of training community health workers and their interventions on cardiovascular disease risk factors among adults in Morogoro, Tanzania: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):552. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2924-9.

Singh A, Nichols M. Nurse-Led Education and Engagement for Diabetes Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(6):e15408. https://doi.org/10.2196/15408.

Guwatudde D, Absetz P, Delobelle P, et al. Study protocol for the SMART2D adaptive implementation trial: a cluster randomised trial comparing facility-only care with integrated facility and community care to improve type 2 diabetes outcomes in Uganda, South Africa and Sweden. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e019981. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019981.

Tran CH, Moore BK, Pathmanathan I, et al. Tuberculosis treatment within differentiated service delivery models in global HIV/TB programming. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 6):e25809. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25809.

Okere NE, Meta J, Maokola W, et al. Quality of care in a differentiated HIV service delivery intervention in Tanzania: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0265307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265307.

Hagey JM, Li X, Barr-Walker J, et al. Differentiated HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review to inform antiretroviral therapy provision for stable HIV-infected individuals in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2018;30(12):1477–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1500995.

Pathmanathan I, Pevzner E, Cavanaugh J, Nelson L. Addressing tuberculosis in differentiated care provision for people living with HIV. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(1):3–3. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.187021.

New Toolkit for Differentiated Care in HIV and TB Programs. https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/news/2015-12-04-new-toolkit-for-differentiated-care-in-hiv-and-tb-programs/ Accessed 24 Apr 2022.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Skaal L. Efficacy of a church-based lifestyle intervention programme to control high normal blood pressure and/or high normal blood glucose in church members: a randomized controlled trial in Pretoria. South Africa BMC Public Health. 2014;14:568. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-568.

Gaziano TA, Bertram M, Tollman SM, Hofman KJ. Hypertension education and adherence in South Africa: a cost-effectiveness analysis of community health workers. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:240. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-240.

Flor LS, Wilson S, Bhatt P, et al. Community-based interventions for detection and management of diabetes and hypertension in underserved communities: a mixed-methods evaluation in Brazil, India, South Africa and the USA. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(6):e001959. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001959.

Barsky J, Hunter R, McAllister C, et al. Analysis of the Implementation, User Perspectives, and Feedback From a Mobile Health Intervention for Individuals Living With Hypertension (DREAM-GLOBAL): Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(12):e12639. https://doi.org/10.2196/12639.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christian Appenzeller-Herzog, information specialist at the Medical University of Basel Library, for the support in developing the search strategy, supporting databases search and the deduplication process.

Funding

This review is funded by the TRANSFORM grant of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation under the ComBaCaL project (Project no. 7F-10345.01.01). NDL receives his salary from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Eccellenza PCEFP3_181355); EF receives his salary from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement (No 801076), through the SSPH + Global PhD Fellowship Programme in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LGF, EF and NDL conceptualized the study and design. LGF, EF, ER and FU performed references screening, data collection and summarization. JH led the literature search and deduplication of sources. LG, ER, EF and NDL drafted the manuscript. RG, TL, AA, FG, JM, and IA reviewed the manuscript draft. HU provided comments to the almost-final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Annex 1.

ScR databases search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández, L.G., Firima, E., Robinson, E. et al. Community-based care models for arterial hypertension management in non-pregnant adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature scoping review and framework for designing chronic services. BMC Public Health 22, 1126 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13467-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13467-4