Abstract

Background

Although childhood undervaccination among single mother families is a concern for child healthcare, their association is still under debate. This study aimed to investigate the association between maternal marital status and the risk of childhood undervaccination and determine the mediating effect of household income.

Methods

We utilised prospective birth cohort from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). Of 104,062 foetal records (children) from 97,413 mothers, 82,462 that included mothers recruited between 2011 and 2014, were analysed. Childhood undervaccination was defined as not having been vaccinated with at least one routine vaccine. A log-binomial regression analysis was used to estimate the risk ratio (RR) for the association between maternal marital status and the risk of childhood undervaccination. A causal mediation analysis was further performed to investigate the proportion of the association mediated by household income.

Results

Among 82,462 children, 3188 and 79,274 had unmarried and married mothers, respectively. Childhood undervaccination was observed in 1053 (33.0%) and 16,901 (21.3%) children of unmarried and married mothers, respectively. Maternal marital status was associated with a higher risk of childhood undervaccination (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 1.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.27 to 1.41). Compared with married and older mothers, both unmarried and older (aRR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.35 to 1.77) and unmarried and younger (aRR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.54 to 1.79) mothers were associated with a higher risk of childhood undervaccination. The causal mediation analysis showed that the proportion mediated by household income was 10.5% (95% CI, 9.9 to 11.0%).

Conclusions

This nationwide, prospective, large-scale birth cohort study found that a household with a single mother was associated with an increased risk of childhood undervaccination, and 10% of this association was explained by household income. These findings underscore the importance of improving the social environment among single mother families, including not only poverty but also working conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vaccination is a major contributor to improved public health, especially among children, preventing 2–3 million deaths every year [1]. The three-dose completion rate of the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis combination vaccine is a measure of vaccination coverage and is over 90% in most developed countries [2]. However, the number of inadequately vaccinated people has been increasing in the United States (US) [3] and Japan [4], which promotes the resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases [5, 6]. Vaccine hesitancy (VH) is defined as the delay in acceptance or the refusal of vaccination, despite available vaccination services [7]. In a survey of the World Health Organisation (WHO) member countries, VH was reported in 93-94% of the countries [8]. The WHO listed VH as one of the ten threats to global health in 2019 [9], and thus, VH and subsequent childhood undervaccination are worldwide concerns.

The association between a single parent family (i.e., parental marital status) and childhood undervaccination has been under examination since the 1980s [10]. A study in the United Kingdom (UK) suggested an association between a single parent family and childhood measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination coverage [11]. In the US, the maternal marital status of being unmarried was associated with delayed childhood vaccination [12]. However, some studies found no association between a single parent family and up-to-date childhood vaccination [13] or indicated conflicting results [14,15,16]. These inconsistencies could be due to insufficient sample sizes, study designs that make it difficult to examine causality, such as cross-sectional studies, and examinations of specific vaccines such as MMR vaccine only. Therefore, the true association between a single parent family and childhood undervaccination remains under investigation.

In this study, we investigated the association between maternal marital status at pregnancy and childhood undervaccination at age 2 years. Most recommended vaccines in Japan are administered before age 2 years [17]. Thus, childhood vaccination status at age 2 years can accurately reflect the childhood vaccination status. Previous studies have also used vaccination status at age 2 years as an outcome [12, 15]. We used a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to represent the causal directions between maternal marital status, childhood undervaccination, and their associated factors, and to identify the potential confounding factors [18]. Single mothers in Japan have a high poverty rate despite their high employment rate [19]. Single mothers spend more time providing childcare and less time working than married mothers. They are also more likely to have difficulty obtaining a high-income job, and their household incomes can fall accordingly. However, it is unlikely that household income will dictate whether or not a mother becomes a single mother. Therefore, although most previous studies have treated the household income as a confounding factor [11, 15, 16, 20, 21], we considered household income as a mediating, rather than confounding, factor in the association between maternal marital status and childhood undervaccination. Furthermore, we conducted a causal mediation analysis to examine the extent to which household income explains the association [22].

Methods

Study design and participants

This cohort study, which utilised data from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), was based on the jecs-ta-20190930 dataset released in October 2019. The JECS is a large-scale, nationwide, multicentre, prospective birth cohort study funded by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan. The detailed study design and baseline characteristics of the JECS cohort were described elsewhere [23, 24]. Mothers in the early pregnancy stage were eligible. Recruitment occurred nationwide between January 2011 and March 2014 in the Study Areas of Japan. Self-administered questionnaires were sent to participants in the first trimester of pregnancy, the second to third trimester, 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year after birth, and until their children turned age 13 years thereafter.

JECS participants who met the following criteria were excluded from this analysis: 1) mothers with stillbirths, miscarriages, or unknown birth outcomes (n = 3739); 2) withdrew consent (n = 19); 3) at least one questionnaire was not completed (n = 15,319); 4) child vaccination data were missing or logically incorrect (n = 2205); and 5) maternal marital status data at pregnancy were missing (n = 318).

Measures

The primary outcome was childhood undervaccination at age 2 years. Two types of vaccines are currently available in Japan. One is a routine vaccine that can be administered at no cost to an individual, and the other is a voluntary vaccine that can be administered at the individual’s expense [17]. Among vaccines that are administered before age 2 years, we analysed those against nine pathogens or diseases that were being routinely administered at the time of participants’ recruitment. The nine pathogens or diseases were Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Streptococcus pneumoniae, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, Bacille de Calmette et Guerin (BCG), measles, and rubella. The following vaccine types were categorised into the “vaccinated” group: combination (such as measles-rubella [MR]) and single vaccines; oral live and inactivated polio vaccines; and multiple vaccines that are administered before age 2 years (such as the Hib vaccine), if they were administered at least once. Childhood undervaccination was defined as not having been vaccinated at age 2 years with at least one or more of these vaccines.

The exposure variable, maternal marital status at pregnancy, was obtained from a questionnaire sent in the first trimester of pregnancy and was categorised as being married (defined as being lawfully or de facto married) or unmarried (defined as never been married, divorced, or widowed).

The characteristics of participants included in our analyses were as follows: maternal age at pregnancy, maternal educational level (high school or lower, junior college, or university or higher), annual household income (< 2 million, 2 to 4 million, 4 to 6 million, or ≥ 6 million JPY), maternal job at pregnancy (housewife or unemployed, part-time or self-employed, or full-time), presence of siblings, maternal smoking status during pregnancy, maternal alcohol intake status during pregnancy [25], maternal use of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy, maternal history of vaccine side effects, and maternal mental component summary (MCS) score during pregnancy. The MCS score was calculated based on the Short-Form 8 (SF-8), a shortened version of the SF-36, an internationally used health-related quality of life scale [26, 27].

Statistical analysis

The DAG was used to represent the causal directions among factors and to identify potential confounding factors [18, 28]. Maternal age at pregnancy (continuous) and maternal educational level (categorical: high school or lower, junior college, or university or higher) were then selected and included in multivariable adjusted models. Since the frequency of outcome was not considered rare, the risk ratio (RR) was estimated by using the log-binomial regression analysis [29]. A subgroup analysis stratified by maternal age and maternal educational level was performed. Combinations of maternal marital status, maternal age, and educational level were also evaluated using the same analysis.

A causal mediation analysis was performed with annual household income as a mediator. Household income was analysed as a continuous variable, with the median income for each category considered as the income for that category. The ≥6 million JPY income category was set to 8 million JPY. The total effect, average causal mediation effect (ACME), average direct effect (ADE), and proportion mediated were estimated [22, 30].

Since the variables used in this study were based on responses to the questionnaires, the occurrence of missing data was predicted. Therefore, multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) was performed to create and analyse 200 datasets each for imputing the missing data. The results of analyses using each dataset were combined based on the Rubin’s rule [31]. Analyses using the complete case dataset were also performed for comparison.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the robustness of the aforementioned analyses. In the sensitivity analysis of the log-binomial regression analysis, E values were calculated for the adjusted RR [32]. That is, the measure of confounding required to fully explain the estimated RR in the presence of uncontrolled confounders was calculated. Since siblings participated in the JECS, some mothers corresponded to more than one child. Children who had the same mother were likely to have similar outcomes, and this had to be considered in the analyses. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis using cluster-robust standard errors and considering the mother as a cluster was conducted [33]. The sensitivity parameter, rho (ρ), which is the correlation between the residuals of the mediator and outcome regressions, was used in the sensitivity analysis for the causal mediation analysis [22, 30, 34]. If there were unadjusted mediator-outcome confounders, the rho value would not be equal to zero [35]. The latter sensitivity analysis was performed using the complete case dataset after confirming that the results of the causal mediation analysis were not largely different between the dataset with missing data imputed and the complete case dataset.

All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.0.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The package “mice (version 3.11.0)” was used to impute missing data by MICE [36], and the package “mediation (version 4.5.0)” was used for the causal mediation and sensitivity analyses [37]. For all the estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and therefore p-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the interaction test in the subgroup analysis, p-values of less than 0.05 were also considered significant.

Results

Cohort selection and characteristics

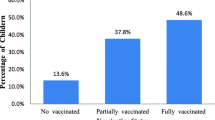

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the cohort selection. Among the 104,062 foetal records (children) from 97,413 mothers participating in the JECS, 21,600 were excluded, based on the set exclusion criteria. Hence, the remaining 82,462 from 77,807 mothers were included in subsequent analyses. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the participants stratified by maternal marital status. Of the 82,462 children, 3188 (3.9%) had unmarried mothers and 79,274 (96.1%) had married mothers. Of these children of unmarried and married mothers, 1053 (33.0%) and 16,901 (21.3%) were undervaccinated, respectively. Considering other exploratory comparisons, children of unmarried mothers had younger mothers, lower maternal educational levels, and lower household income than those of married mothers, despite higher employment rates of their mothers. Each vaccine coverage stratified by maternal marital status is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Log-binomial regression analysis associated with childhood undervaccination

Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the DAG used in our study. Figure 2 shows the results of the log-binomial regression analysis for all participants and subgroups. After adjusting for maternal age and maternal educational level, maternal marital status was associated with a higher risk of childhood undervaccination (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.41). The subgroup analysis indicated an interaction between maternal marital status and maternal educational level (P-value for interaction, 0.02).

Log-binomial regression analysis including all participants and the subgroup analyses. All estimates and their 95% confidence intervals are risk ratios of unmarried mothers compared to married mothers for childhood undervaccination. The analysis was adjusted for maternal age (continuous) and educational level (categorical). No., Number; CI, confidence interval; cRR, crude risk ratio; aRR, adjusted risk ratio

Figure 3 shows the results of the log-binomial regression analysis using combinations of marital status, age, and educational level. Compared with being married and older (aged ≥35 years), being unmarried and older (RR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.35 to 1.77) and unmarried and younger (aged ≥24 years) (RR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.54 to 1.79) among mothers had a higher risk of childhood undervaccination.

Log-binomial regression analysis using the combinations of maternal marital status and maternal age or educational level. a Married mothers aged ≥35 years were the reference group. b Married mothers who were university graduate or higher were the reference group. RR, risk ratio; Univ., university; H.S., high school

Causal mediation analysis with household income

Table 2 provides the results of the causal mediation analysis with maternal marital status as the exposure, childhood undervaccination as the outcome, and household income as the mediator. Estimates, except for the proportion mediated, were calculated as risk differences. The total effect was 0.0783 (95% CI, 0.0623 to 0.09), the ACME was 0.0082 (95% CI, 0.0068 to 0.01), and the proportion mediated was 0.105 (95% CI, 0.099 to 0.11) in the adjusted model. The results of the analysis using the complete case dataset are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Sensitivity analyses

The E value for the adjusted RR of unmarried versus married mothers and the lower limit of the 95% CI were 2.01 and 1.86, respectively. The log-binomial regression analysis with cluster-robust standard errors, considering the mother as a cluster, showed that the adjusted RR for childhood undervaccination among unmarried mothers to married mothers was 1.34 (95% CI, 1.27 to 1.41), similar to the main analysis shown in Fig. 2. As shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2, concerning the causal mediation analysis, the results were not significantly different between the dataset with missing data imputed and the complete case dataset. Therefore, we calculated the sensitivity parameter, rho, using the complete case dataset. The rho is also given in Table 2. The rho at which the CI of ACME included zero was − 0.07 to − 0.06 and − 0.06 for the crude and adjusted models, respectively. The rho was slightly closer to zero when maternal age and maternal educational level were added as covariates.

Discussion

This nationwide, prospective birth cohort study investigated the association between maternal marital status and childhood undervaccination at age 2 years. Unmarried mothers were approximately 1.3 times more likely to have childhood undervaccination than married mothers. Furthermore, although the social backgrounds of younger and older unmarried mothers may be different, our findings suggest that both are at risk of childhood undervaccination. We subsequently conducted the causal mediation analysis using household income as the mediator. Approximately 10% of the association between maternal marital status and childhood undervaccination was explained by household income.

Clarifying the association between the two can provide an evidence-based justification for social support. The vaccines surveyed in this study were provided at no cost to the individuals. The result of the mediation analysis, which showed that the mediating effect of household income was low, was consistent. Another possible barrier to childhood vaccination is the lack of time for child healthcare among households with single mothers. Compared to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, single mothers in Japan have higher poverty rates despite higher employment rates [19]. Our study similarly showed that unmarried mothers had higher employment rates and lower household incomes than married mothers. To solve this problem, improvement in the working conditions among single mothers is needed. Furthermore, for example, simplification of vaccination systems, institutionalisation of paid leave for child healthcare, and vaccination programs at the mother’s workplace can facilitate access to child vaccination for single mothers who are busy with both home and work. We not only investigated the mediating effect of household income but also highlighted the problem of managing work and child healthcare among single mothers.

Supplementary Table S1 shows that the vaccine coverage after age 1 year, such as for measles, was less than that of the vaccines given in early infancy, such as pneumococcus. This suggested that some children were vaccinated in early infancy but gradually dropped out. In contrast, some families did not vaccinate their children at all. Of the children of unmarried and married mothers, only 12/3188 (0.4%) and 191/79,274 (0.2%), respectively, were not vaccinated at all. The background characteristics of families who gradually dropped out and did not vaccinate their children at all may be different. However, we could not compare the characteristics between the two groups because of the small sample size of families who were not vaccinated at all.

Comparison with other studies

Several previous studies had similar findings. A US cross-sectional study of 14,810 children aged 24 to 35 months suggested an association between maternal marital status and severely delayed childhood vaccinations (adjusted odds ratio, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1 to 1.6) after adjusting for covariates, including maternal age and maternal educational level [12]. Another UK cohort study of 14,578 children aged 3 years showed that a single parent household was associated with childhood uptake of MMR vaccine (adjusted RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.60) [11]. We found a similar association using the larger sample size in our prospective birth cohort data for all recommended vaccines at age 2 years in Japan.

Some previous studies have also examined the association between household income and childhood vaccination status. However, regardless of the timing of the studies, they did not find an association between the two. A US study of 4431 children conducted in 1994 indicated no association between household income and up-to-date childhood vaccination [38]. Another Canadian study of 3604 children conducted in 2013 suggested that household income and childhood uptake of measles vaccine did not show a clear trend [15]. These studies did not find an association between household income and childhood vaccination because of lack of power due to the relatively small sample sizes. Otherwise, these results could be evidence suggesting that household income should be considered as a mediating factor for a causally higher-level factor (i.e., maternal marital status examined in our study). We conducted a causal mediation analysis based on this hypothesis.

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of our study was its large-scale and prospective birth cohort data. Previous studies were mostly designed as cross-sectional studies [39]. Our study design is more suitable for investigating causal associations. We followed children and their mothers until the children turned 2 years old. Since most vaccines are administered in infancy, up to 1 year old, childhood undervaccination may have occurred already by this time. A previous study showed an association between childhood vaccination status at 1 year old and maternal marital status [40]. Therefore, the follow-up period from early pregnancy until the children turn age 2 years is sufficient to estimate the causal association between the two.

Our study had some limitations. First, the characteristics of the JECS cohort may not accurately reflect those of Japanese pregnant women. The JECS participants were recruited through Co-operating health care providers and government agencies. Mothers who have negative views on vaccination (i.e., those with VH) may avoid visiting them. Hence, the JECS cohort may have underestimated the frequency of VH. However, the JECS recruited sufficient participants nationwide. Since the coverage for each vaccine was not largely different from those reported previously [41], the effect of this limitation might be negligible. In addition, the enrolled participants were mothers, and single fathers were not included in this study. Since single mothers and single fathers can have different socioeconomic conditions, the results of this study may not be generalisable to single fathers. Second, variables may have been misclassified due to the self-reported JECS surveys. In our study, unmarried mothers had a lower socioeconomic status than married mothers. Thus, unmarried mothers may be more likely to give responses that differ from the true vaccination status of their children. Misclassification of outcomes may be more likely among unmarried mothers, causing a differential misclassification. Moreover, the maternal marital status at pregnancy can change during the study. Some mothers may marry after childbirth, and others may divorce. Biases can occur if the exposure factor (marital status) changes during the period up to the occurrence of the outcome (childhood vaccination). Third, our analyses may have unmeasured residual confounding. Therefore, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the E value and the sensitivity parameter, rho. The E value was higher than the RRs for the other measured variables and the rho was close to zero. Thus, it is unlikely that unmeasured confounders would completely account for the observed association and explain the estimated mediating effect. Furthermore, the causal mediation analysis in this study was conducted only with household income. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, several factors, such as maternal employment status and living with grandparents, were considered as mediating factors in the association between maternal marital status and childhood undervaccination. In order to examine effective support for single mothers, analysing the mediating effects of factors other than household income is also needed.

How to improve childhood vaccination coverage in single mother families

Poverty in single mother families as well as VH are serious problems. The average poverty rate in OECD countries, including Japan, has been 9.8% for families with two parents. In contrast, for single mother families, it has been 32.5% [42]. Although the “welfare-to-work” interventions have been attempted to improve employment status and single mother family incomes, the effects are limited [43]. Moreover, single mother families in Japan have the lowest incomes among OECD countries despite their high employment rates [19].

Vaccination system issues, such as supply and geographical accessibility, have been identified as reasons for undervaccination in low and middle-income countries [44]. In contrast, among single mothers in Japan and other developed countries, lack of time for child healthcare due to busy work, including housework, can contribute to undervaccination. The high rates of employment and poverty among single mothers in Japan indicate their busyness. Both financial support and comprehensive improvement in the socioeconomic status of single mother families are needed. Moreover, being a single mother is not in itself a modifiable risk factor. Instead, the causal mediation analysis conducted in our study can help investigate interventions that are effective for improving childhood vaccination coverage of single mother families.

Conclusions

We investigated the association between maternal marital status and childhood vaccination status in a Japanese nationwide birth cohort. Furthermore, we examined the mediating effect of household income on this association. When mothers were unmarried, childhood undervaccination increased by approximately 1.3 times. Moreover, 10% of this association was explained by household income. Our study suggests both an effect of financial support and the problem of balancing work and child healthcare among single mothers. The focus needs to be directed towards the main problems of maternal working conditions and poverty.

Availability of data and materials

Data are unsuitable for public deposition because of the ethical restrictions and legal framework of Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 30 May 2003 amendment on 9 September 2015) to publicly deposit data containing personal information. Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also restrict the open sharing of epidemiologic data. All inquiries about access to data were sent to: jecs-en@nies.go.jp. The person responsible for handling enquiries sent to this e-mail address is Dr. Shoji F. Nakayama, JECS Programme Office, National Institute for Environmental Studies.

Abbreviations

- US:

-

United States

- VH:

-

Vaccine hesitancy

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- MMR:

-

Measles-mumps-rubella

- DAG:

-

Directed acyclic graph

- JECS:

-

Japan Environment and Children’s Study

- Hib:

-

Haemophilus influenzae type b

- BCG:

-

Bacille de Calmette et Guerin

- MR:

-

Measles-rubella

- MCS:

-

Mental component summary

- SF-8:

-

Short-Form 8

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- ACME:

-

Average causal mediation effect

- ADE:

-

Average direct effect

- MICE:

-

Multivariate imputation by chained equations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

References

WHO. Health topics - Vaccines and Immunization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/vaccines-and-immunization. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

WHO. Immunization dashboard. https://immunizationdata.who.int/. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

Olive JK, Hotez PJ, Damania A, Nolan MS. The state of the antivaccine movement in the United States: a focused examination of nonmedical exemptions in states and counties. PLoS Med. 2018;15(6):e1002578.

Shimizu K, Kinoshita R, Yoshii K, Akhmetzhanov AR, Jung S, Lee H, et al. An investigation of a measles outbreak in Japan and China, Taiwan, China, March-May 2018. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2018;9(3):25–31.

Hall V, Banerjee E, Kenyon C, Strain A, Griffith J, Como-Sabetti K, et al. Measles outbreak - Minnesota April-May 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(27):713–7.

Robison SG, Liko J. The timing of pertussis cases in unvaccinated children in an outbreak year: Oregon 2012. J Pediatr. 2017;183:159–63.

MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4.

Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form data-2015-2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3861–7.

WHO. Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

Hutchins SS, Escolan J, Markowitz LE, Hawkins C, Kimbler A, Morgan RA, et al. Measles outbreak among unvaccinated preschool-aged children: opportunities missed by health care providers to administer measles vaccine. Pediatrics. 1989;83(3):369–74.

Pearce A, Law C, Elliman D, Cole TJ, Bedford H, Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group. Factors associated with uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR) and use of single antigen vaccines in a contemporary UK cohort: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7647):754–7.

Luman ET, Barker LE, Shaw KM, McCauley MM, Buehler JW, Pickering LK. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in the United States: days undervaccinated and number of vaccines delayed. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1204–11.

Dombkowski KJ, Lantz PM, Freed GL. Risk factors for delay in age-appropriate vaccination. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(2):144–55.

Luman ET, McCauley MM, Shefer A, Chu SY. Maternal characteristics associated with vaccination of young children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(Suppl 1):1215–8.

Gilbert NL, Gilmour H, Wilson SE, Cantin L. Determinants of non-vaccination and incomplete vaccination in Canadian toddlers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(6):1447–53.

Périnet S, Kiely M, De Serres G, Gilbert NL. Delayed measles vaccination of toddlers in Canada: associated socio-demographic factors and parental knowledge, attitudes and beliefs. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(4):868–74.

Know-VPD. Immunization Schedule. https://www.know-vpd.jp/dl/schedule_multilingual/vc_schedule_english.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37–48.

OECD (2011), Doing Better for Families. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011.

Pati S, Feemster KA, Mohamad Z, Fiks A, Grundmeier R, Cnaan A. Maternal health literacy and late initiation of immunizations among an inner-city birth cohort. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(3):386–94.

Jeong YW, Park BH, Kim KH, Han YR, Go UY, Choi WS, et al. Timeliness of MMR vaccination and barriers to vaccination in preschool children. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(2):247–56.

Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods. 2010;15(4):309–34.

Kawamoto T, Nitta H, Murata K, Toda E, Tsukamoto N, Hasegawa M, et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health. 2014;14(25):25.

Michikawa T, Nitta H, Nakayama SF, Yamazaki S, Isobe T, Tamura K, et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). J Epidemiol. 2018;28(2):99–104.

Yokoyama Y, Takachi R, Ishihara J, Ishii Y, Sasazuki S, Sawada N, et al. Validity of short and long self-administered food frequency questionnaires in ranking dietary intake in middle-aged and elderly Japanese in the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study for the next generation (JPHC-NEXT) protocol area. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(8):420–32.

Ware J, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993.

Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y. Manual of the SF-8 Japanese version (in Japanese). Kyoto: Institute for Health Outcome and Process Evaluation Research; 2004.

Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, Liskiewicz M, Ellison GT. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):1887–94.

McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–3.

Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D, Yamamoto T. Unpacking the black box of causality: learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2011;105(4):765–89.

Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987.

VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–74.

Colin Cameron A, Miller DL. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):317–72.

Imai K, Keele L, Yamamoto T. Identification, inference and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):51–71.

Ato García M, Vallejo Seco G, Ato Lozano E. Classical and causal inference approaches to statistical mediation analysis. Psicothema. 2014;26(2):252–9.

Buuren S, Oudshoorn GK. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67.

Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J Stat Softw. 2014;59(5):1–38.

Suarez L, Simpson DM, Smith DR. The impact of public assistance factors on the immunization levels of children younger than 2 years. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(5):845–8.

Tauil Mde C, Sato AP, Waldman EA. Factors associated with incomplete or delayed vaccination across countries: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(24):2635–43.

Adokiya MN, Baguune B, Ndago JA. Evaluation of immunization coverage and its associated factors among children 12-23 months of age in Techiman municipality, Ghana, 2016. Arch Public Health. 2017;75:28.

WHO, UNICEF. Japan: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2019 revision. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/jpn.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

OECD. OECD family database - 4. Child outcomes (CO) - Child poverty. http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

Gibson M, Thomson H, Banas K, Lutje V, McKee MJ, Martin SP, et al. Welfare-to-work interventions and their effects on the mental and physical health of lone parents and their children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD009820.

Rainey JJ, Watkins M, Ryman TK, Sandhu P, Bo A, Banerjee K. Reasons related to non-vaccination and under-vaccination of children in low and middle income countries: findings from a systematic review of the published literature, 1999-2009. Vaccine. 2011;29(46):8215–21.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants and the members of the JECS. We would like to thank Yuko Kachi (Kitasato University, Tokyo, Japan) for providing expertise in child public health, Izumi Nakayama (Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan) for statistical analysis, and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

List of JECS Group members and their affiliations

Michihiro Kamijima5, Shin Yamazaki6, Yukihiro Ohya7, Reiko Kishi8, Nobuo Yaegashi9, Koichi Hashimoto10, Zentaro Yamagata11, Hidekuni Inadera12, Takeo Nakayama13, Hiroyasu Iso14, Masayuki Shima15, Youichi Kurozawa16, Narufumi Suganuma17, Koichi Kusuhara18, Takahiko Katoh19

5 Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan

6 National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan

7 National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan

8 Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan

9 Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan

10 Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan

11 University of Yamanashi, Chuo, Japan

12 University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan

13 Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

14 Osaka University, Suita, Japan

15 Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan

16 Tottori University, Yonago, Japan

17 Kochi University, Nankoku, Japan

18 University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, Japan

19 Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the above government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

HK, AG, and SI designed the study. CK, SI, and JECS Group contributed to acquisition of the data. HK and AG analysed the data, and KY provided statistical expertise. HK drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for our study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University (approval number: B200900053, approved on 16 October 2020). The JECS protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of the Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies (Ethical Number: No.100910001) and the Ethics Committees of all participating institutions (listed in Acknowledgement). Both our study and the JECS were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuroda, H., Goto, A., Kawakami, C. et al. Association between a single mother family and childhood undervaccination, and mediating effect of household income: a nationwide, prospective birth cohort from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). BMC Public Health 22, 117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12511-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12511-7