Abstract

Background

The objective of the study was to analyze the associations of family aspects, physical fitness, and physical activity with mental-health indicators in a sample of adolescents from Colombia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study carried out in a sample of 988 adolescents (11-17 years-old) from public schools in Montería. Mental-health indicators were evaluated: Stress, depression, anxiety, happiness, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and subjective wellness. Family aspects included family affluence, functionality, and structure. These variables, along with physical activity and screen time, were measured with questionnaires. A fitness score was established by assessing the components of fitness: Flexibility, cardiorespiratory fitness, grip strength, and lower-limb strength. Associations were analyzed by multivariate linear regression models.

Results

Nuclear family structure was associated with lower stress level (− 1.08, CI: − 1.98 - -0.18), and family functionality was associated with all the studied mental-health indicators (Stress: -0.11, CI: − 0.17 - -0.06; depression: -0.20, CI: − 0.25 - -0.16; trait anxiety: -0.13, CI: − 0.18 - -0.09; state anxiety: -0.12, CI: − 0.17 - -0.08; happiness: 0.09, CI: 0.07 - 0.1; HRQL: 1.13, CI: 0.99 - 1.27; subjective wellness: 1.67, CI: 1.39 - 1.95). Physical activity was associated (β, 95% Confidence Interval (CI)) with depression (− 0.27, − 0.57 - -0.02), trait anxiety (− 0.39, CI: − 0.65 - -0.13), state anxiety (− 0.30, CI: − 0.53 - -0.07), happiness (0.14, CI: 0.06 - 0.22), HRQL (3.63, CI: 2.86 – 4.43), and subjective wellness (5.29, CI: 3.75 – 6.83). Physical fitness was associated with stress (− 0.80, CI: − 1.17 - -0.43), state anxiety (− 0.45, CI: − 0.73 - -0.17), and HRQL (1.75, CI: 0.82 - 2.69); screen time was only associated with stress (0.06, CI: 0.02 - 0.11).

Conclusions

Family aspects were associated with mental health indicators, especially family functionality which was associated all mental-health indicators. Similarly, fitness, physical activity, and screen time were associated with the studied indicators of mental health. Particularly, physical activity was associated with all the mental-health indicators, except stress, which was only associated with screen time. Physical fitness was associated with stress, anxiety, and HRQL. Future studies could explore the causal relationships of fitness, physical activity and screen time with mental health in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental health is an invaluable resource for personal development and adequate levels of social functioning. Currently, mental-health problems represent a prominent field for public health. This is mainly due to its high prevalence globally and to its adverse effects on the burden of global morbidity [1] and mortality [2]. It has been estimated that one in three adults has experienced alterations in their mental health in the course of their life [3]. The study of mental health in the school-age population is relevant due to its role in the development, in all its aspects – physical, social, intellectual and emotional; also, half of these alterations begin during adolescence [4]. Unfortunately, mental well-being is an elusive condition for much of the adolescent population. For example, it has been estimated that between 10 and 20% of adolescents on the planet have poor mental health [5]. In the case of Colombia, this estimate is considerably higher, reaching 33% [4].

Historically, the study of mental health has centered its interest on psychopathological symptoms and negative mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, stress among others. More recently, positive psychology has emerged and incorporated positive domains and components to mental health. Here, the constructs of well-being, subjective wellness, life satisfaction, happiness and the like, are the focus of attention [6]. These constructs may be understood as cognitive and affective processes around life satisfaction and positive emotional experiences [7]. These positive mental processes may protect against the onset of mental health disorders [8].

Mental health is a complex concept; therefore, its determinants and associated factors are multiple, among which stand out personal aspects (state of health, previous experiences, habits related to health), family (quality of the family environment, economic conditions), and social (quality of social relationships with peers and friends), the built environment, among others [9]. In particular, previous studies have documented that high levels of physical activity, low levels of screen time, and sufficient sleep time are behaviors associated with higher levels of mental health [10, 11]. Furthermore, similar associations of physical activity with depression [12] and happiness [13], and physical fitness with mental health [14] have been reported. In addition, randomized controlled trials have documented the positive effects of physical activity on depression [15] and self-esteem [16]. Regarding the family, it has been pointed out that the nuclear family structure generates a protective environment for mental health in young people [17] and that family environment with economic deprivation can negatively affect adolescent mental health [18].

These antecedents reflect an advance in the understanding of factors associated with mental health in adolescents. However, more research attention is needed in low- and middle-income countries. Consequently, the objective of this study was to explore the associations of family aspects, physical fitness, and physical activity with mental-health indicators in a sample of adolescents in Colombia. In this study, mental-health indicators are explored, including negative entities such as stress, depression and anxiety, and positive entities such as happiness, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and subjective well-being. Identifying these factors associated with mental-health indicators could inform early interventions aimed at strengthening adolescents’ mental health.

Methods

In this study, information was used from the project “Determinants of academic achievement, health, and wellness in school-age children” (De-Redes, 2018), and conducted in the city of Montería, Colombia. It is an observational study with a cross-association design carried out in adolescents from public schools, between 11 and 17 years old. The city has 63 public schools, of which eight urban and two rural were randomly selected. In each school, a course per grade, between grades 7 and 10, was randomly selected. In each course, all students of that course were invited to participate. The sample consisted of 988 students who voluntarily participated in the study; they signed the informed assent and their parents authorized their participation by signing the informed consent. The study was conducted following the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki and its protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Antioquia’s University Institute of Physical Education.

Measurements

Mental-health indicators

Seven mental-health indicators were measured, taken as outcome variables: the level of stress was measured with the Spanish version of the Children’s Daily Stress Inventory (CDSI), consisting of 25 items (score total between 0 and 25) [19]. To estimate the level of depression, the abbreviated version of the inventory of depression in children (Children’s Depression Inventory, CDI:S) was used, made up of ten items (total score between 0 and 20) [20]. Anxiety was measured with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC), consisting of six items for each type of anxiety (total score between 5 and 24) [21]. Happiness was evaluated with the Subjective Happiness Scale, composed of four items (total score between 4 and 28, which was then averaged) [22]. HRQL was measured with the KidScreen-27 instrument, made up of 27 items (total score between 27 and 100) [23];]; and subjective well-being was estimated with the Spanish adaptation of the Personal Well-being Index- School Children (PWI-SC) [24], and applied to the Latin American context [25], composed of 12 items (total score between 0 and 120). All these instruments had acceptable levels of internal consistency (αstress = .70, αdepression = .77, αtrait anxiety = .72, αstate anxiety = .70, αhappiness = .60, αHRQOL = .91, and αsubjective wellness = .92).

Family aspects

Three aspects of the family were analyzed: As a proxy for socioeconomic position, the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) was used; it inquiries about four elements that reflect the material conditions of the family: one’s own room, Internet access at home, number of computers and cars [26]. The responses were added and gave a score between 0 and 8, to which tertiles were computed, indicating a better economic position as the tertile increases. The family structure was investigated to identify three types of structure: nuclear, single parent, and other. Family functionality was explored using the Family Apgar instrument [27], which contains five items exploring how satisfied the adolescent is with their family functions. Each item can be scored between zero and five, resulting in a score ranging from zero to 25.

Physical fitness

Physical fitness was evaluated in different capacities. Flexibility was evaluated with the sit-and-reach test, which measures the flexibility of the lower back region and the hamstring muscles, and its values were recorded in centimeters [28]. The evaluation of the explosive strength of the lower limbs was carried out with the long-jump test, performing a forward jump with the greater impulse of the lower limbs, and the distance reached in centimeters was recorded [29]. Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured with the 20-m shuttle-run test, designed to evaluate the ability of the cardiorespiratory system to transport and use oxygen [30]; it consists of going and coming back in a space of 20 m, at an initial speed of 8.5 ∙ km h-1, with increments of 0.5 km h-1 every minute until reaching maximum performance, recording the number of laps completed. With this information, the equation was applied to calculate the maximum oxygen consumption [31]. The grip strength was evaluated with the Jamar Handgrip Dynamometer (Sammons Preston, Bolingbrook, Illinois, USA.). The participant executed the test in each hand; the average was recorded, and the values were normalized by body weight. Each of the four physical-fitness variables was standardized for sex and age, by calculating z-scores, which were averaged to obtain a fitness z-score.

Physical activity and screen time

Physical activity was measured with the Spanish version of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescent (PAQ-A) [32], of which acceptable correlation values have been reported with accelerometry [32]. In the questionnaire, a score between 1 and 5 was obtained; the higher the values, the higher the physical activity level. For screen time, the Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ) [33], in which different domains of sedentary behavior were explored, including screen time made up of the use of television, computer, and video -games. The responses in these domains were added to obtain the number of hours of screen time per day. The instrument is valid for the classification of sedentary behavior [34].

Sociodemographic variables

The body weight and height of the participants were measured to obtain the Body Mass Index (BMI); a Health or Meter scale with a precision of 200 g was used for body weight, and a Seca-brand height rod was used for height, measured in millimeters. Classification of BMI was based on z-scores from World Health Organization reference measurements [35]. The participants reported their age and sex, and the urban or rural location of the schools was recorded. Urban and rural areas are defined by the government based on political-administrative categories of the degree of urbanization. Urban areas are characterized by having a high degree of urbanization and high residential density. While rural areas are defined as the residual of the urban, that is, areas with scattered residences and low residential density [36].

Analysis

Descriptive statistics, proportions, and mean ± standard deviation were calculated after verifying the normal distribution in the variables considering the values of asymmetry and kurtosis (values between − 2 and + 2). Mean differences of mental health scores according to categorical variables were tested with independent samples T-Tests and one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey tests. For the analysis of the association between the variables analyzed and the mental-health indicators, the bivariate associations (raw) were initially explored, and then the multivariate linear regression models (adjusted) were constructed. Bivariate and multivariate associations were performed separately for each mental-health indicator. This is, binary associations between each one of the independent variables (sociodemographic variables, family aspects, physical fitness, physical activity, and screen time) and the seven mental health indicators were analyzed. Then, for the multivariate models and following the Homer-Lemeshow criterion [37], variables with p-values < .25 in the bivariate association were selected and included in the models. For the variable of family structure, which have three categories, dummy variables were created to fit the linear models. In total, seven separate models were analyzed, one for each mental health indicator. Interaction term between sex and age were explored and its associations with all of the analyzed mental health indicators (a three-way interaction) were not significant. The 95% confidence intervals were obtained, and the significance level was established at p-value <.05. The analyzes were carried out with the SPSS Statistical Program for Windows v.24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Results

The descriptive characteristics are shown in Table 1. In total, 988 adolescents with an average age of 14.9 ± 1.5 years participated; girls made up 53.1% of the sample (n = 525), and about four out of every five adolescents were students from schools located in the urban zone. The FAS tertiles with the highest proportion of adolescents were – in their order – the second (41.6%), the third (31.6%) and the first (26.8%). One in three adolescents reported belonging to a nuclear family, and 26.1% (n = 258) reported belonging to a single-parent family, and the rest (7.5%) (n = 74) to another type of family structure. A prevalence of overweight of 16.3% (n = 161) was found. Table 1 also shows the results of the scores obtained in the measurement scales of the mental-health indicators, physical fitness, and physical activity level, as well as the average number of hours per day of screen time (7.2 ± 4.3).

Mean differences of mental-health indicators according to categories of independent variables are shown in Table 2. Compared to boys, girls reported higher levels of stress, depression, trait anxiety, and state anxiety. Boys had higher scores of HRQL and subjective wellness. Students from urban schools reported higher scores of stress and depression, and lower subjective wellness score than students from rural schools. Compared to adolescents from nuclear families, adolescents with a family structure categorized as other, reported higher levels of stress (pairwise comparisons). There were differences in levels of HRQL across categories of family structure, but pairwise comparisons were not statistically significant.

The results of the bivariate (crude) linear associations between the variables studied and the mental-health indicators are shown in Table 2. The coefficients indicate that as age was positively associated with stress, trait and state anxiety, and negatively associated with HRQL and subjective well-being. Similarly, being a girl was significantly associated with higher stress levels, depression, trait and state anxiety, and lower levels of HRQL and subjective well-being. Belonging to urban schools was significantly associated with higher levels of stress and depression and lower levels of subjective well-being. The occurrence of overweight was significantly associated with lower subjective well-being values.

Regarding family aspects, shown in Table 3, it was found that FAS tertiles were positively associated with HRQL. Belonging to a single parent family was negatively associated with depression, and being member of a nuclear family was negatively associated with stress and positively associated with HRQL. Family’s functionality score was negatively associated with stress, depression, trait and state anxiety, and positively associated with happiness, HRQL, and subjective well-being. Physical fitness was negatively associated with stress and state anxiety and positively associated with HRQL. Regarding physical activity, it was found that this behavior was negatively associated with stress, depression, trait and state anxiety and positively associated with happiness, HRQL, and subjective well-being. Finally, screen time was positively associated with stress and anxiety.

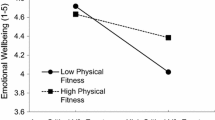

The results of the analysis of the multivariate linear associations (adjusted) between the variables studied and the mental-health indicators are shown in Table 4. The regression models included adjustment variables that had p-values < .25 in the bivariate association. After including the adjustment variables, it was found that age and screen time were positively associated with stress, and family’s functionality score, physical fitness, and physical activity were negatively associated with stress. Being a girl and belonging to urban schools were associated with higher stress score, and being a member of a nuclear family was negatively associated with lower stress score. The linear model for depression, shows that being a girl and belonging to an urban school were associated with higher depression level. Family’s functionality and physical activity scores were negatively associated with depression. The linear models for trait and state anxiety showed similar results. Both anxiety dimensions were positively associated with age, and negatively associated with family’s functionality and physical activity scores. Being a girl was associated with higher trait and state anxiety level. In addition, physical fitness was negatively associated with state anxiety score.

Regarding positive components of mental health, linear regression models showed that family’s functionality and physical activity scores were positively associated with happiness. Age was negatively associated with HRQL, and being a girl and belonging to urban schools were associated with lower HRQL score. Family’s functionality score, physical fitness, and physical activity were positively associated with HRQL. Finally, age was negatively associated with subjective wellness. Being a girl and belonging to urban schools were associated with lower subjective wellness score. Family’s functionality score and physical activity were positively associated with subjective wellness. BMI was not associated with any of the mental-health indicators analyzed.

Discussion

The study’s objective was to analyze the associations of family aspects, physical fitness, and physical activity with mental-health indicators in a sample of adolescents from Colombia. These results indicated that adolescents’ mental health is strongly related with the characteristics of the family, with the levels of physical fitness, and with physical activity and sedentary behavior, aspects that will be discussed separately.

Demographic factors, family factors, and mental-health indicators

The findings reveal that female sex was associated with higher stress, depression, trait and state anxiety scores, and with lower HRQL score. Similar results were reported in a systematic review indicating that girls presented more mental health problems than boys [38]. In addition, results showed that family affluence was associated with HRQL, that family structure was associated with stress, and that family functionality was associated with the seven mental-health indicators analyzed. These findings are consistent with previous studies. For example, previous studies have documented that a family with appropriate functionality exerts a protective effect against depression in schoolchildren [39] and that adolescents from families with poor functionality are more likely to report depressive symptoms [40].

Among the mechanisms postulated to understand the relationship between family functioning and mental health, it has been pointed out that families with hostile and neglectful relationships trigger alterations in the nervous and hormonal systems of their children, causing emotions of detachment, rejection, and alienation in them, negatively affecting their mental health [41]. On the other hand, a positive, supportive and cohesive family environment promotes optimal levels of mental health in adolescents [42].

Fitness, physical activity, screen time, and mental-health indicators

In turn, physical fitness was associated with stress, state anxiety, and HRQL; physical activity was associated with all the mental-health indicators studied except stress, which was the only mental-health indicator found to be associated with screen time. The results of this study were consistent with previous reports regarding the association between physical fitness and mental health [14, 43]. Similar to the results of this study, associations have been indicated between physical activity with depression [12, 44], anxiety [44], happiness [13], with HRQL [45, 46], and with subjective well-being [47]. However, the absence of association of physical activity with anxiety and stress has been documented [12]. In addition, it has been reported that the association between physical activity and psychosocial problems are significantly stronger in boys than in girls [43]. In this regard, we found no evidence that the relationships between fitness, physical activity and mental health varied with sex. Associations of time spent watching television with depression [48, 49], anxiety [48], HRQL [50], and subjective well-being [51] have been documented in the literature, but these associations were not found in this study. Similar to that reported in the literature [12, 14], no associations were found between the BMI and mental-health indicators analyzed in this study.

As for the mechanisms that help explain the relationship between physical fitness and mental health, a biological mechanism has been suggested, indicating that aerobic exercise causes an antidepressant effect via the endocannabinoid system [52]. In turn, it has been suggested that physical activity causes an increase in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and this increase is associated with a reduction in levels of anxiety and depression [53]. Additionally, a psychosocial mechanism has been postulated, taking into account that participation in sports is popular during adolescence [54], and this may facilitate the development of socialization skills, considered a protective factor for mental health [55]. Although the explanatory mechanisms for the relationship between sedentary behavior and mental health are not well established, a psychosocial mechanism has been suggested by pointing out that excessive screen time can induce feelings of loneliness when performed in settings of social isolation, thus leading to poor mental health [56]. A behavioral mechanism is also proposed in the literature, indicating that – as more time is spent on the screen –physical activities [56] and adequate sleep [57] are reduced, negatively affecting adolescent mental health.

Implications of the findings

The findings reported in this study have implications on the intervention with physical activity and the mental health of adolescents in the family, school, and community contexts since – consistent with other studies – we have found an association between the level of physical fitness, physical activity, and mental health indicators, as well as the relationship between screen time and a relevant mental-health indicator for this population (i.e., stress). These associations may be further explored to evaluate the effects of interventions on mental health in adolescent population. In this sense, we propose that emphasis should be placed on strengthening, in quality and quantity, physical activity programs inside and outside of school, in order to promote physical activity habits, stimulate the development of health-related physical fitness and, as far as possible, reduce the time spent on the screen. At the same time, wellness programs in schools should consolidate, both individually and collectively, the integration of family aspects and the students’ lifestyles as a human-development strategy. On the other hand, these results establish the need to look for a cause-effect relationship between physical activity/physical fitness and variables of mental-health outcomes. In this sense, trials that contemplate causal-mediation analysis [58, 59], aimed at exploring variables that have a mediating role on the effect of physical exercise on mental health in young people, may contribute to the construction of robust evidence for researchers and health and exercise professionals [60].

Limitations and strengths of the study

The results presented should be analyzed under the limitations of this study. In the first instance, it is highlighted that it is a cross-sectional study; therefore, any causal inference, for example, between physical fitness/physical activity with mental health, should be excluded. Second, health indicators, physical activity and screen time were evaluated through self-reporting questionnaires that, although validated, may present risks of information and classification bias. In the same way, it should be considered that this study does not record history or prevalence of any type of disease (physical or mental), economic situation, violence, or factors related to the family or community environment where the adolescent lives that, in a certain way, can have a confounding effect on the association presented here. Finally, school location (urban and rural) is a school-level variable that could be affecting mental health of students from the same school. With this, the assumption of independent observations may be compromised. The exploration of this aspect requires a multilevel analysis. However, this approach is beyond the scope of the article. On the other hand, this study presents methodological strengths, such as the size of the sample types implemented that allowed including adolescents from the urban and rural sectors, and that represents a predominantly low-income population, characteristic of a low-high-income country such as Colombia. In addition, various indicators of mental health were taken into account (i.e., level of stress, level of depression, anxiety, subjective happiness, HRQL, and subjective wellness), and simultaneously the level of physical activity, screen time (sedentary behavior), and health-related physical fitness were evaluated (i.e., grip strength and lower limbs, cardiorespiratory capacity, and flexibility), which allowed a more complete analysis to be presented.

Conclusion

This study shows that family affluence was associated with HRQL, that family structure was associated with stress, and that family functionality was associated with all mental-health indicators. The level of physical activity was associated with all indicators of mental health, except stress. On the other hand, physical fitness was related to stress, anxiety, and HRQL, while screen time was only associated with stress. In line with other research, the study findings have important practical implications that reveal the importance of promoting mental health in adolescents through school and community programs that promote the practice of physical activity, the development of health-related physical fitness, and decreased screen time. On the other hand, more experimental evidence of the effect of physical exercise on mental-health indicators in adolescents is required, suggesting causal-mediation analysis to explain the relationship between physical activity and mental health, as well as the possible mechanisms involved.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDI:S:

-

Children’s Depression Inventory

- CDSI:

-

Children’s Daily Stress Inventory

- FAS:

-

Family Affluence Scale

- HRQL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- PAQ-A:

-

Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescent

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PF:

-

Physical fitness

- PWI-SC:

-

Personal Well-being Index- School Children

- SBQ:

-

Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire

- STAIC:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children

References

Alonso J, Chatterji S, He Y. The burdens of mental disorders: global perspectives from the WHO world mental health surveys. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

World Health Organization. Meeting report on: Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/excess_mortality_meeting_report.pdf?ua=1.

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038.

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, R DEG, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey initiative. World Psychiatry 2007;6(3):168-176,

Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1.

Pilgrim D, Rogers A, Pescosolido B. The SAGE handbook of mental health and illness: SAGE Publications; 2011.

Kashdan TB, Biswas-Diener R, King LA. Reconsidering happiness: the costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. J Posit Psychol. 2008;3(4):219–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802303044.

Keyes C. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002:207–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197.

Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(4):392–407. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.928270.

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Colman I, Goldfield GS, Janssen I, Wang J, Podinic I, et al. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep duration and their associations with depressive symptoms and other mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00976-x.

Oswald TK, Rumbold AR, Kedzior SGE, Moore VM. Psychological impacts of “screen time” and “green time” for children and adolescents: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237725.

Maenhout L, Peuters C, Cardon G, Compernolle S, Crombez G, DeSmet A. The association of healthy lifestyle behaviors with mental health indicators among adolescents of different family affluence in Belgium. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):958. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09102-9.

van Woudenberg TJ, Bevelander KE, Burk WJ, Buijzen M. The reciprocal effects of physical activity and happiness in adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01058-8.

Avitsland A, Leibinger E, Haugen T, Lerum O, Solberg RB, Kolle E, et al. The association between physical fitness and mental health in Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):776. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08936-7.

Bailey AP, Hetrick SE, Rosenbaum S, Purcell R, Parker AG. Treating depression with physical activity in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychol Med. 2018;48(7):1068–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717002653.

Ekeland E, Heian F, Hagen KB. Can exercise improve self esteem in children and young people? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(11):792–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2004.017707.

Barrett AE, Turner RJ. Family structure and mental health: the mediating effects of socioeconomic status, family process, and social stress. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(2):156–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650504600203.

Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026.

Trianes-Torres MV, Mena MJB, Fernández-Baena FJ, Escobar-Espejo M, Maldonado-Montero EF, Muñoz-Sánchez ÁM. Evaluación del estrés infantil: Inventario Infantil de Estresores Cotidianos (IIEC). Psicothema. 2009;21(4):598–603 http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72711895016.

Knight D, Hensley VR, Waters B. Validation of the Children’s Depression Scale and the Children’s Depression Inventory in a prepubertal sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1988;29(6):853–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00758.x.

Fioravanti-Bastos ACM, Cheniaux E, Landeira-Fernandez J. Development and validation of a short-form version of the Brazilian state-trait anxiety inventory. Psicol-Reflex Crit. 2011;24:485–94. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722011000300009.

Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46(2):137–55. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006824100041.

Vélez CM, Lugo LH, García HI. Validez y confiabilidad del 'Cuestionario de calidad de vida KIDSCREEN-27′ versión padres, en Medellín. Colombia Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2012;41:588–605 http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-74502012000300010&nrm=iso.

Cummins RA, Lau A. Personal wellbeing index – (English ) 3rd edition. Australia: Melbourne; 2005.

Oyanedel JC, Alfaro J, Mella C. Bienestar Subjetivo y Calidad de Vida en la Infancia en Chile. 2015;13(1).

Currie CE, Elton RA, Todd J, Platt S. Indicators of socioeconomic status for adolescents: the WHO health behaviour in school-aged children survey. Health Educ Res. 1997;12(3):385–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/12.3.385.

Forero L, Avendaño M, Duarte Z, Campo A. Consistencia interna y análisis de factores de la escala APGAR para evaluar el funcionamiento familiar en estudiantes de básica secundaria. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2006;XXXV(1):23-29.

Wells K, Dillon E. The sit and reach—a test of back and leg flexibility. Res Q. 1952;23(1):115–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10671188.1952.10761965.

Castro-Piñero J, Ortega FB, Artero EG, Girela-Rejón MJ, Mora J, Sjöström M, et al. Assessing muscular strength in youth: usefulness of standing long jump as a general index of muscular fitness. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(7):1810–7. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ddb03d.

Leger L, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6(2):93–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640418808729800.

Mahar MT, Guerieri AM, Hanna MS, Kemble CD. Estimation of aerobic fitness from 20-m multistage shuttle run test performance. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 2):S117–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.07.008.

Martinez-Gomez D, Martinez-de-Haro V, Pozo T, Welk GJ, Villagra A, Calle ME, et al. Reliability and validity of the PAQ-A questionnaire to assess physical activity in Spanish adolescents. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2009;83(3):427–39. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1135-57272009000300008.

Rosenberg D, Norman GJ, Wagner N. Reliability and validity of the sedentary behavior questionnaire (SBQ) for adults. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(6):697–705. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.6.697.

Rey-López JP, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Verloigne M, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Gracia-Marco L, et al. Reliability and validity of a screen time-based sedentary behaviour questionnaire for adolescents: the HELENA study. Eur J Pub Health. 2012;22(3):373–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr040.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660–7. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.07.043497.

Departamento Nacional de Estadística. Censa nacional de población y vivienda 2018. https://www.dane.gov.co/files/censo2018/informacion-tecnica/CNPV-2018-manual-conceptos.pdf.

Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 1989.

Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, Hayatbakhsh R. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(7):606–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414533834.

Manalel JA, Antonucci TC. Beyond the nuclear family: Children's social networks and depressive symptomology. Child Dev. 2020;91(4):1302–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13307.

Guerrero-Muñoz D, Salazar D, Constain V, Perez A, Pineda-Cañar CA, García-Perdomo HA. Association between family functionality and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Fam Med. 2021;42(2):172–80. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.19.0166.

Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(2):330–66. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.2.330.

Anthony EK, Stone SI. Individual and contextual correlates of adolescent health and well-being. Fam Soc. 2010;91(3):225–33. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3999.

Wheatley C, Wassenaar T, Salvan P, Beale N, Nichols T, Dawes H, et al. Associations between fitness, physical activity and mental health in a community sample of young British adolescents: baseline data from the fit to study trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1):e000819. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000819.

Zhu X, Haegele JA, Healy S. Movement and mental health: Behavioral correlates of anxiety and depression among children of 6–17 years old in the U.S. Ment Health Phys Act. 2019;16:60-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.04.002

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Standage M, Tremblay MS, Katzmarzyk PT, Hu G, Kuriyan R, et al. Associations between meeting combinations of 24-h movement guidelines and health-related quality of life in children from 12 countries. Public Health. 2017;153:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.010.

Dumuid D, Maher C, Lewis LK, Stanford TE, Martín Fernández JA, Ratcliffe J, et al. Human development index, children's health-related quality of life and movement behaviors: a compositional data analysis. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(6):1473–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1791-x.

Garcia-Hermoso A, Hormazabal-Aguayo I, Fernandez-Vergara O, Olivares PR, Oriol-Granado X. Physical activity, screen time and subjective well-being among children. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2020;20(2):126–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.03.001.

Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, et al. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev Med. 2015;73:133–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.029.

Hoare E, Millar L, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Skouteris H, Nichols M, Jacka F, et al. Associations between obesogenic risk and depressive symptomatology in Australian adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(8):767–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-203562.

Arango CM, Páez DC, Lema L, Sarmiento O, Parra D. Television viewing and its association with health-related quality of life in school-age children from Montería, Colombia. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2014;12:68–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2014.07.002.

Martínez-López EJ, Hita-Contreras F, Moral-García JE, Grao-Cruces A, Ruiz JR, Redecillas-Peiró MT, et al. Association of low weekly physical activity and sedentary lifestyle with self-perceived health, pain, and well-being in a Spanish teenage population. Sci Sport. 2015;30(6):342–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2015.04.007.

Heyman E, Gamelin FX, Goekint M, Piscitelli F, Roelands B, Leclair E, et al. Intense exercise increases circulating endocannabinoid and BDNF levels in humans-possible implications for reward and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(6):844–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.017.

Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(9):464–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011.

Eime R, Payne W, Harvey J. Trends in organised sport membership: impact on sustainability. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(1):123–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2007.09.001.

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98.

Ohannessian CM. Media use and adolescent psychological adjustment: an examination of gender differences. J Child Fam Stud. 2009;18(5):582–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9261-2.

Primack BA, Swanier B, Georgiopoulos AM, Land SR, Fine MJ. Association between media use in adolescence and depression in young adulthood: a longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):181–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.532.

Daniel RM, De Stavola BL, Cousens SN, Vansteelandt S. Causal mediation analysis with multiple mediators. Biometrics. 2015;71(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/biom.12248.

Hicks R, Tingley D. Causal mediation analysis. Stata J. 2011;11(4):605–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1201100407.

Lynch BM, Dixon-Suen SC, Ramirez Varela A, Yang Y, English DR, Ding D, et al. Approaches to improve causal inference in physical activity epidemiology. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(1):80–4. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0515.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the principals, physical-education teachers, parents, and schoolchildren of the public schools in Montería who participated in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL-G: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

CA-P: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation.

CE-L: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

JLP: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation.

JP-P: Investigation, Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

ML-S: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

WW-F: Project administration, Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

FP-V: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Relevant guidelines

The study was conducted following the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent to participate

Participants were those who signed the informed assent and their parents authorized their participation by signing the informed consent.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Antioquia’s University Institute of Physical Education, in Medellín, Colombia (project number 2017-021, approval number 038, November 28-2017).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lema-Gómez, L., Arango-Paternina, C.M., Eusse-López, C. et al. Family aspects, physical fitness, and physical activity associated with mental-health indicators in adolescents. BMC Public Health 21, 2324 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12403-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12403-2