Abstract

Background

Hypertension is highly prevalent and is one of the modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular outcomes. Isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH), however, tends to be ignored due to insufficient recognition. We sought to depict the clinical manifestation of IDH and isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) to find a more efficient way to improve the management.

Methods

Patients with primary hypertension aged over 18 years were investigated from all over the country using convenience sampling during 2017–2019. IDH was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg. ISH was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg.

Results

A total of 8548 patients were screened, and 8475 participants were included. The average age was 63.67 ± 12.78 years, and males accounted for 54.4%. Among them, 361 (4.3%) had IDH, and 2096 had ISH (24.7%). Patients with IDH (54.84 ± 13.21 years) were much younger. Aging turned out to be negatively associated with IDH but positively associated with ISH. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed BMI was a significant risk factor for IDH (OR 1.30, 95%CI 1.05–1.61, p = 0.018), but not for ISH (OR 1.05, 95%CI 0.95–1.16, p = 0.358). Moreover, smoking was significantly associated with IDH (OR 1.36, 95%CI 1.04–1.78, p = 0.026) but not with ISH (OR 1.04, 95%CI 0.90–1.21, p = 0.653).

Conclusions

Patients with IDH were much younger, and the prevalence decreased with aging. BMI and smoking were remarkably associated with IDH rather than ISH. Keeping fit and giving up smoking might be particularly efficient in the management of young patients with IDH.

Trial registration

NCT03862183, retrospectively registered on March 5, 2019.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension is highly prevalent and is one of the most modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. Isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH) and isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) are two particular types of hypertension. However, compared to ISH, IDH tend to be ignored either by patients or by physicians. As reported in the PEACE Study, 86.1% of those IDH were untreated [1].

Recently, the significance of IDH has been challenged. McEvoy et al. reported that IDH, by 2017 ACC/AHA definitions [2], was not associated with increased cardiovascular outcomes [3]. That study might be limited by the population’s age, and the results should be cautiously generalized to young patients. Yue et al. found that in 21,441 participants, patients aged 35–59 years with stage 1 hypertension defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline had a significantly increased risk of CVD risks over a 15-year period. However, in patients aged ≥60 years, stage 1 hypertension was not associated with increased CVD risks [4].

Actually, in a recent network meta-analysis, each 10 mmHg reduction in systolic BP and each 5 mmHg reduction in diastolic BP have been reported to be associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular events, and stroke [5]. Lee et al. reported that among 6 million participants aged 20–39 years, stage 1 IDH turned out to be associated with higher CVD risks after 13.2 years follow up [6]. Thus, the management of IDH in young patients should be highlighted rather than ignored.

However, adherence to antihypertensive medication is far from optimal, especially in younger patients. Tiffany et al. reported that among 23.8 million hypertensive adults, the nonadherence rate was around 31%, and the highest nonadherence rate of 58.1% was seen in the youngest population aged 18–34 years in the U.S. in 2015 [7].

Besides antihypertensive drugs, lifestyle management also plays an essential role in managing hypertension concerning the high nonadherence rate in young patients [8,9,10]. Nevertheless, lifestyle management may affect different types of hypertension like IDH and ISH, which are considered to have different pathophysiological mechanisms and will result in various features [11]. However, our knowledge of IDH is still insufficient, as is stated in the guidelines [2, 12]. We sought to depict the prevalence and clinical manifestation of IDH, ISH, systolic and diastolic hypertension (SDH), and normotension in a multicenter observational study (UPPDATE Study) to find a more efficient way to improve the management of IDH.

Methods

We carried out a nationwide cross-sectional study (UPPDATE study, Survey on BP, Lipids and cardiovascular risks in the outpatient hypertensives and Continuing Medical Education Program) in hospitals all over the country from 2017 to 2019 using convenience sampling. These hospitals were located in the three municipalities directly under the Central Government (Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing) and 14 provinces all over the country (Table 1). Patients with hypertension, either under lifestyle management or antihypertensive medication, were included. The inclusion criteria were 1) ≥ 18 years old; 2) primary hypertension; 3) providing the written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were 1) secondary hypertension, 2) severe liver or renal disease, 3) mental illness, or active cancer. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (2017–282-1). Age categories were defined as < 25 years, > 85 years, and every 10-year apart from 25 to 85 years. Hypertension was defined according to the 2018 ESC/ESH guideline for the management of hypertension using office BP [12]. Therefore, IDH was defined as SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP ≥ 90 mmHg; ISH was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg; Systolic and diastolic hypertension (SDH) was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and DBP ≥ 90 mmHg; Normotension was defined as SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg. Elevated BMI was defined as overweight and obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) according to the 2000 WHO standard [13]. The smoking history was defined as those who had a history of smoking, whether stopped or not. Patients with antihypertensive agents were defined as those under the treatment of any antihypertensive drugs recommended by the guidelines [12]. Predictor variables were selected based on the guidelines of hypertension and previous literature [12, 14, 15].

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA 13.1. Two-sides Student’s t-test or ANOVA were used for continuous variables, and Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Both the forward stepwise method and the backward stepwise method were used to reach the multivariate logistic regression model. Variables with p < 0.25 in univariable logistic regression analysis would be included to build the model. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 8548 participants were screened, and 73 of them were excluded due to missing covariates. Finally, 8475 participants were included. The average age was 63.67 ± 12.78 years. Males accounted for 54.4%. 18.5% of them had a habit of smoking, and 89.4% were under antihypertensive agents. The average BMI was 24.83 ± 3.85 kg/m2 (Table 2).

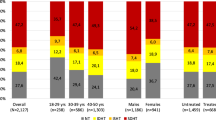

Among them, 361(4.3%) patients had IDH, 2096 (24.7%) patients had ISH, 2584 (30.5%) patients had SDH, and 3434 (40.5%) patients had normotension. Patients with IDH were the youngest (54.84 ± 13.21 years) among those with ISH (66.87 ± 12.09 years), SDH (60.39 ± 13.12 years), and Normotension (65.11 ± 11.90 years). However, patients with IDH had the highest BMI (26.47 ± 6.53 kg/m2) among those with ISH (24.70 ± 3.77 kg/m2), SDH (25.15 ± 3.92 kg/m2), and normotension (24.50 ± 3.38 kg/m2). The smoking rate was also the highest in patients with IDH (27.4%) among those with ISH (17.1%), SDH (22.2%), and normotension (15.8%). While antihypertensive treatment rate was the lowest in patients with IDH (82.0%) among those with ISH (88.4%), SDH (83.5%), and normotension (95.1%). Statin treatment rate was also the lowest in patients with IDH (46.1%) among those with ISH (64.3%), SDH (53.2%), and normotension (58.2%) (Table 2).

The proportion of IDH of the total population decreased with aging, while the proportion of ISH increased with aging (Table 3, Fig. 1). Logistic regression analysis showed the gradually decreasing risk of IDH and the continuously increasing risk of ISH for every 10-year aging, which means aging was positively associated with ISH but negatively associated with IDH (Table 4, Fig. 2). Younger patients were more likely to have IDH, while older patients were more likely to have ISH.

Additionally, patients with IDH had a higher BMI (26.47 ± 6.53 kg/m2) than those with ISH (24.70 ± 3.77 kg/m2). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for age, gender, smoking history, and antihypertensive agents, BMI remained as a significant risk factor for IDH (OR 1.30, 95%CI 1.05–1.61, p = 0.018), but not for ISH (OR 1.05, 95%CI 0.95–1.16, p = 0.358), which means the BMI target has not been achieved well and remained to be taken seriously, particularly in patients with IDH (Table 4, Fig. 2).

Moreover, smoking was more prevalent in IDH (27.4%) than in ISH (17.1%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that, after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, and antihypertensive agents, smoking remained significantly associated with IDH (OR 1.36, 95%CI 1.04–1.78, p = 0.026) but not with ISH (OR 1.04, 95%CI 0.90–1.21, p = 0.653). Therefore, besides BMI, stop smoking is another recommended lifestyle change that should be seriously concerned (Table 4, Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our study found that IDH and ISH were two distinctive types of hypertension. Both of them were age-dependent. However, IDH was more prevalent in young and middle-aged patients, while ISH was more prevalent in middle-aged and old patients. Obesity and smoking, the risk factors for hypertension and lifestyle-changing targets, were significantly associated with IDH but not ISH. Therefore, BMI and smoking habits should be concerned more seriously and might be particularly efficient in young patients with IDH.

Recently, diastolic BP was not considered as important as systolic BP, and IDH was challenged to be regarded as the risk factor for incident cardiovascular outcomes by some studies [3, 16, 17]. Moreover, Mahajan et al. reported that few patients with IDH were aware of having hypertension and were poorly managed in the China PEACE Million Persons Project [1].

Nevertheless, in a worldwide study, Yan Li et al. reported that IDH was remarkably associated with cardiovascular events, particularly in those below 50 years [18]. Additionally, IDH was associated with urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, particularly in patients below 55 years [19]. The inconsistent results may mainly lie in the age of the study population. It has already been recognized that after 50 years old, the systolic BP continuously increases with age, while on the other hand, the diastolic BP starts to decrease with age. Therefore, IDH is more prevalent in young and middle-aged patients, but ISH is more prevalent in middle-aged and old patients [8, 20]. Thus, the management of IDH should be highlighted rather than ignored in younger patients [21,22,23].

Obesity and smoking are the two major risk factors for the development of hypertension, which can be modified by improving lifestyle management [2, 24]. As obesity and smoking are highly prevalent in young adults, it would be particularly essential to prevent cardiovascular disease by early lifestyle management. BMI trajectories are significantly associated with the incidence of hypertension in young adults, which suggested the importance of early prevention [25]. Recently, smoking has been confirmed to be associated with an increased risk of masked hypertension, especially in heavy smokers [26]. In our study, BMI was remarkably associated with the prevalence of IDH but was not associated with ISH, which might suggest that lowering BMI might be an effective way to lower diastolic BP and improve the management of IDH. Smoking was significantly associated with the prevalence of IDH as well. It was not associated with ISH, either. Thus, giving up smoking might also be exceptionally efficient in the management of IDH. More longitudinal studies are needed in the early IDH interference and management.

The weakness of our study was that it was a cross-sectional study with convenience sampling, which would cause selection bias. The results could not be generalized to those who never came to hospitals and we could not tell the causal relationship between BMI, smoking, and IDH. Patients with ISH were older and might have better lifestyle management after years of medical contact to have lower BMI and smoking rates. Moreover, as we know, patients with hypertension have different weight on risk factors. Other risk factors might affect more in patients with ISH. In addition, unmeasured factors like diet, physical activity levels, socio-economic status, educational levels, and the presence of HMOD were not included in the analysis, which would prevent the study from providing a whole picture of the characteristics of hypertensive patients and would also cause bias. However, we could find that more efforts were needed in lifestyle management concerning BMI and smoking in patients with IDH than those with ISH. Keeping fit and giving up smoking might be critical to lower the diastolic BP and to manage IDH.

The strength of our study was that it was a multi-center study recruiting patients from all over the country with a relatively large sample. Thus, it would be appropriate for the results to be generalized to the hypertensive patients who attend to hospitals in China. Additionally, our study population had a wide span of ages, which facilitated us to depict the features of IDH in relatively young patients and helped fill the insufficiency of data in patients with IDH. The result suggested the importance of lifestyle management in the early-onset patients with IDH, besides antihypertensive agents.

In conclusion, IDH and ISH had different features. Patients with IDH were much younger, and the prevalence decreased with aging. On the contrary, patients with ISH were much older, and the prevalence increased with aging. As IDH was a disease of young and middle-aged patients, such subtype management should be highlighted rather than ignored. BMI and smoking status were the two factors mainly associated with IDH rather than ISH. Besides antihypertensive agents, keeping fit and giving up smoking might contribute a lot to managing young patients with IDH.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mahajan S, Zhang D, He S, Lu Y, Gupta A, Spatz ES, et al. Prevalence, awareness, and treatment of isolated diastolic hypertension: insights from the China PEACE million persons project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e012954. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012954.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269–324. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066.

McEvoy JW, Daya N, Rahman F, Hoogeveen RC, Blumenthal RS, Shah AM, et al. Association of Isolated Diastolic Hypertension as defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure guideline with incident cardiovascular outcomes. JAMA. 2020;323(4):329–38. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.21402.

Qi Y, Han X, Zhao D, Wang W, Wang M, Sun J, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risk associated with stage 1 hypertension defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(11):1201–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.056.

Wei J, Galaviz KI, Kowalski AJ, Magee MJ, Haw JS, Narayan KMV, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular events among users of different classes of antihypertension medications: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921618. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21618.

Lee H, Yano Y, Cho SMJ, Park JH, Park S, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Cardiovascular risk of isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension in young adults. Circulation. 2020;141(22):1778–86. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044838.

Chang TE, Ritchey MD, Park S, Chang A, Odom EC, Durthaler J, et al. National Rates of nonadherence to antihypertensive medications among insured adults with hypertension, 2015. Hypertension. 2019;74(6):1324–32. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13616.

Sheriff HM, Tsimploulis A, Valentova M, Anker MS, Deedwania P, Banach M, et al. Isolated diastolic hypertension and incident heart failure in community-dwelling older adults: insights from the cardiovascular health study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;238:140–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.142.

Niiranen TJ, Rissanen H, Johansson JK, Jula AM. Overall cardiovascular prognosis of isolated systolic hypertension, isolated diastolic hypertension and pulse pressure defined with home measurements: the Finn-home study. J Hypertens. 2014;32(3):518–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000070.

Wang Y, Xing F, Liu R, Liu L, Zhu Y, Wen Y, et al. Isolated diastolic hypertension associated risk factors among Chinese in Anhui Province, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(4):4395–405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404395.

Timpson NJ, Harbord R, Davey Smith G, Zacho J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Does greater adiposity increase blood pressure and hypertension risk?: Mendelian randomization using the FTO/MC4R genotype. Hypertension. 2009;54(1):84–90. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130005.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii, 1–253.

He H, Pa L, Pan L, Simayi A, Mu H, Abudurexiti Y, et al. Effect of BMI and its optimal cut-off value in identifying hypertension in Uyghur and Han Chinese: a Biethnic study from the China National Health Survey (CNHS). Int J Hypertens. 2018;2018:1508083–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1508083.

Wang J, Zhu Y, Jing J, Chen Y, Mai J, Wong SH, et al. Relationship of BMI to the incidence of hypertension: a 4 years' cohort study among children in Guangzhou, 2007-2011. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):782. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1997-6.

Arima H, Anderson C, Omae T, Woodward M, Hata J, Murakami Y, et al. Effects of blood pressure lowering on major vascular events among patients with isolated diastolic hypertension: the perindopril protection against recurrent stroke study (PROGRESS) trial. Stroke. 2011;42(8):2339–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606764.

Strandberg TE, Salomaa VV, Vanhanen HT, Pitkala K, Miettinen TA. Isolated diastolic hypertension, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure as predictors of mortality during a follow-up of up to 32 years. J Hypertens. 2002;20(3):399–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200203000-00014.

Li Y, Wei FF, Thijs L, Boggia J, Asayama K, Hansen TW, et al. Ambulatory hypertension subtypes and 24-hour systolic and diastolic blood pressure as distinct outcome predictors in 8341 untreated people recruited from 12 populations. Circulation. 2014;130(6):466–74. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004876.

Wei FF, Li Y, Zhang L, Xu TY, Ding FH, Staessen JA, et al. Association of target organ damage with 24-hour systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels and hypertension subtypes in untreated Chinese. Hypertension. 2014;63(2):222–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01940.

Mittal C, Singh M, Bakhshi T, Ram Babu S, Rajagopal S, Ram CVS. Isolated diastolic hypertension and its risk factors in semi-rural population of South India. Indian Heart J. 2019;71(3):272–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2019.07.007.

Li Y, Wei FF, Wang S, Cheng YB, Wang JG. Cardiovascular risks associated with diastolic blood pressure and isolated diastolic hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(11):489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-014-0489-x.

McEniery CM, Yasmin WS, Maki-Petaja K, Mcdonnell B, Sharman JE, et al. Increased stroke volume and aortic stiffness contribute to isolated systolic hypertension in young adults. Hypertension. 2005;46(1):221–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000165310.84801.e0.

Citoni B, Figliuzzi I, Presta V, Cesario V, Miceli F, Bianchi F, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of isolated systolic hypertension in young: analysis of 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring database. J Hum Hypertens. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00493-9.

Xie K, Bao L, Jiang X, Ye Z, Bing J, Dong Y, et al. The association of metabolic syndrome components and chronic kidney disease in patients with hypertension. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-1121-5.

Fan B, Yang Y, Dayimu A, Zhou G, Liu Y, Li S, et al. Body mass index trajectories during young adulthood and incident hypertension: a longitudinal cohort in Chinese population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(8):e011937. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.011937.

Zhang DY, Huang JF, Kang YY, Dou Y, Su YL, Zhang LJ, et al. The prevalence of masked hypertension in relation to cigarette smoking in a Chinese male population. J Hypertens. 2020;38(6):1056–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002392.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our appreciation to the UPPDATE Investigators who contributed a lot to improve the UPPDATE Study. They are Prof. Jianping Bin (Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University), Prof. Zhenyun Chen (The 113th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army), Prof. Hong Chen (Peking University people’s Hospital), Prof. Jiangtian Chen (Peking University people’s Hospital), Prof. Yugang Dong (The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University), Prof. Danchen Gao (The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University), Prof. Weijian Huang (The First Affiliated Hospital, Wenzhou Medical School), Prof. Tingbo Jiang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University), Prof. Jiangang Jiang (Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology), Prof. Suxin Luo (The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University), Prof. Yan Li (Ruijing Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University), Prof. Jinchao Lu (The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University), Prof. Jiehua Li (The First Affiliated Hospital, Anhui Medical University), Prof. Xiaoping Li (Qilu Hospital of Shandong University), Prof. Wei Mao (Zhejiang Province Chinese Medicine Hospital), Prof. Daoquan Peng (Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University), Prof. Peng Qu (The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University), Prof. Shangming Song (Shandong Province Hospital), Prof. Yan Tang (The First People’s Hospital of Guiyang), Prof. Junkui Wang (Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital), Prof. Hui Wang (Jiangsu Province Hospital), Prof. Yongxin Wu (The First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province), Prof. Huichao Wang (Wuhan Union Hospital), Prof. Biao Xu (Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital), Prof. Zaixin Yu (First Xiangya Hospital, Central South University), Prof. Xinhua Yin (The First Affiliated Hospital, Harbin Medical University), Prof. Fang Yuan (Qilu Hospital of Shandong University), Prof. Xinjun Zhang (West China Hospital of Sichuan University), Prof. Min Zhang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University), Prof. Zixin Zhang (The First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University), Prof. Zhiming Zhu (Daping Hospital of Army Medical University).

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Health Committee (grant number ZY (2018–2020)-ZWB-1001-CPJS16).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Prof. KX contributed to the investigation, the analysis, the interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. Prof. XG contributed to the organization of the investigation and revised the manuscript. Prof. LB contributed to the management of the investigation and the database. Prof. YS contributed to review and approve the version to be published. Prof. HS reviewed and approved the version to be published. Prof. YL contributed to the design and supervision of the study and approved the version to be published. All gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (2017–282-1). All of the patients included in our study have provided the written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was supported by the Shanghai Health Committee (grant number ZY (2018-2020)-ZWB-1001-CPJS16).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, K., Gao, X., Bao, L. et al. The different risk factors for isolated diastolic hypertension and isolated systolic hypertension: a national survey. BMC Public Health 21, 1672 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11686-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11686-9