Abstract

Background

Timely and appropriate evidence-based practices during antenatal care improve maternal and neonatal health. There is a lack of information on how pregnant women and families perceive antenatal care in Bangladesh. The aim of our study was to develop targeted client communication via text messages for increasing antenatal care utilization, as part of an implementation of an electronic registry for maternal and child health.

Methods

Using a phenomenological approach, we conducted this qualitative study from May to June 2017 in two sub-districts of Chandpur district, Bangladesh. We selected study participants by purposive sampling. A total of 24 in-depth interviews were conducted with pregnant women (n = 10), lactating women (n = 5), husbands (n = 5), and mothers-in-law (n = 4). The Health Belief Model (HBM) was used to guide the data collection. Thematic analysis was carried out manually according to the HBM constructs. We used behavior change techniques to inform the development of targeted client communication based on the thematic results.

Results

Almost no respondents mentioned antenatal care as a preventive form of care, and only perceived it as necessary if any complications developed during pregnancy. Knowledge of the content of antenatal care (ANC) and pregnancy complications was low. Women reported a variety of reasons for not attending ANC, including the lack of information on the timing of ANC; lack of decision-making power; long-distance to access care; being busy with household chores, and not being satisfied with the treatment by health care providers. Study participants recommended phone calls as their preferred communication strategy when asked to choose between the phone call and text message, but saw text messages as a feasible option. Based on the findings, we developed a library of 43 automatically customizable text messages to increase ANC utilization.

Conclusions

Pregnant women and family members had limited knowledge about antenatal care and pregnancy complications. Effective health information through text messages could increase awareness of antenatal care among the pregnant women in Bangladesh. This study presents an example of designing targeted client communication to increase antenatal care utilization within formal scientific frameworks, including a taxonomy of behavior change techniques.

Trial registration

ISRCTN69491836. Registered on December 06, 2018. Retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Antenatal care (ANC) provided by skilled health professionals includes risk identification, prevention and management of pregnancy-related or concurrent diseases, health education, and health promotion [1, 2]. Implementation of timely and appropriate evidence-based practices during ANC improves health as well as saves the lives of mothers and newborns [3]. In addition, ANC is a window of opportunity for social, cultural, physiological, and emotional support to pregnant women, through effective communication to increase health care utilization [4, 5]. ANC also provides an opportunity to prevent and manage concurrent diseases through integrated service delivery [6, 7].

Sixty-four percent of pregnant women attend a minimum of four ANC visits worldwide, suggesting the need for context-specific interventions to address ANC utilization [5, 8]. In Bangladesh, 47 % of pregnant women attend four ANC visits, and only 37% of women receive their first ANC before 16 weeks of gestation [9]. This low coverage of ANC may be influenced by socio-cultural beliefs, demographic characteristics, and the performance of the health system [5]. Although physical access has not been reported as a significant problem, utilization is low despite multiple efforts, including demand-side financing projects [10]. Women’s perceptions of care is a key issue limiting service utilization [11, 12]. Women’s negative perceptions of the quality of ANC and the expectation that pregnancy complications are rare may prevent adequate ANC utilization. Therefore, health education about the benefits of ANC is essential prior to, and during, the early stages of pregnancy. It provides an opportunity for dialogue between pregnant women and care providers to promote ANC utilization, birth preparedness, and increase awareness of complications [13, 14].

Maternal knowledge of complications is an essential precondition for routine ANC attendance for identification of early pregnancy-related complications, especially because most of these complications have no symptoms before severe illness develops. Studies from low- and middle-income countries, including Bangladesh, have reported that knowledge about pregnancy complications is low [15,16,17,18]. Complications such as anemia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are common in South East Asia including Bangladesh [19,20,21,22]. Therefore, screening for these three conditions during pregnancy is essential, especially given that there are few symptoms at the early stages of these illnesses. Timely ANC attendance is critical for early screening for and identification of anemia, GDM, and gestational hypertension, thereby preventing later complications.

The use of digital health interventions is increasingly prioritized to strengthen healthcare systems, with many low- and middle-income countries implementing digital health technologies to address specific challenges in maternal and child health. Digital health interventions have the potential to improve ANC attendance through behavior change messages and targeted client communication (TCC) [23]. TCC is defined as the transmission of targeted health content to a specified population or an individual within a predefined health or demographic group [24]. In low-income countries, digital health interventions have shown promise as an effective way for TCC to influence behavior and encourage women to access preventive services including ANC [25]. In Bangladesh, about 94% of households have a mobile phone and 60% of currently married women have their own mobile phone [9, 26]. Mobile phone features such as text messaging via Short Message Service (SMS), voice calls, Multimedia Message Service (MMS), or interactive voice recording have been found to be effective in increasing the uptake of different health care services [27,28,29]. While in some low resource settings, mobile phone text messaging has been shown to increase ANC attendance [30], others have found that telephone call reminders, compared to text messaging reminders, were more effective in increasing ANC attendance [31]. To guide policy-making, more information is needed on which methods can effectively increase ANC utilization in Bangladesh.

The objective of this study was to develop targeted client communication via text messages for promoting antenatal care utilization, as part of an implementation of an electronic registry for maternal and child health. We explored pregnant women’s health-seeking behaviors, knowledge about pregnancy complications, and women’s and families’ perceptions of self-care practices during pregnancy mechanisms that might support the implementation of TCC to increase attendance, and subsequently develop TCC messages guided by these findings. This study is one of the formative components of the eRegMat (electronic registry Matlab) trial, a large cluster-randomized controlled trial to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of an eRegistry on health care services delivered to pregnant women and newborn babies in rural Bangladesh (trial registration number: ISRCTN69491836). In the eRegMat trial, we are comparing an interactive eRegistry (longitudinal client records with health worker decision support and TCC via text messages), developed within the District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2 platform) to a ‘silent registry’ (with longitudinal client records only) on improvements in the quality of care during the antenatal, childbirth, and postnatal periods.

Methods

Design

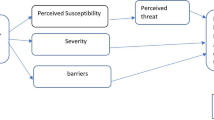

A qualitative research using phenomenological approach, guided by the Health Belief Model (HBM), was carried out to explore perceptions of ANC and pregnancy complications [32]. The HBM focuses on six constructs: perceived susceptibility and severity of complications; perceived benefits of care, self-efficacy; and barriers and cues to action to attend care. We used the HBM to find out individuals’ perceived knowledge of pregnancy care and practice, to predict why and how women seek care during pregnancy. We developed the interview guidelines using HBM constructs for performing in-depth interviews in order to map the lived experience of pregnancy care (see Additional file 1). The interview guidelines focused on anemia, GDM, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Questions on preferred strategies for communication and participants’ views on text message use to address knowledge gaps were also included in the interview guidelines. We pretested all the interview guidelines and based on the feedback, tools were refined and modified for final data collection. The interview guidelines were developed in English and translated to Bangla by the investigators of the study.

Study site and population

The study was conducted in Matlab South and Matlab North sub-districts in Chandpur District, Bangladesh. The study site mostly consists of rural and riverine delta areas of Bangladesh and is located 80–85 km southeast of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, maternal and child health care services are provided by the two separate departments of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Domiciliary community health workers from both departments provide health education on maternal and child health at the village level [33, 34]. At the primary care level, maternal health services are provided at Community Clinics (CC) and Union Health and Family Welfare Centres (UH&FWC) [18]. The UH&FWC cover a population of about 25,000, while CC cover an average of 6000 [33, 34]. The study population included pregnant and postpartum women, husbands, and mothers-in-law of pregnant women. We included husbands and mothers-in-law along with the pregnant and postpartum women as they are the prime household decision-makers of pregnancy-care seeking in this community [35] .

Sampling

We used purposive sampling to select study participants from the pregnancy register of domiciliary community health workers, based on the inclusion criteria. The following groups were eligible for inclusion in the study: 1) women who were nullipara, primipara or multipara; 2) women with or without antenatal complications during a recent pregnancy; 3) postpartum women who delivered a live baby within 1 month of the interview; 4) husbands of pregnant women; and 5) mothers-in-laws of pregnant women. Husbands and mothers-in-law were not related to the pregnant or postpartum women included in the interviews.

Data collection

In-depth interviews were chosen as a first step to elicit a vivid picture of the participant’s perspective on and experiences with pregnancy care. In-depth interviews are considered to be a non-threatening method to gather such data. Participants were free to express their true opinions as we assured them that the information shared will not be linked back to the individual participant. Two research investigators with experience in qualitative research conducted all the in-depth interviews. Before the data collection, investigators were well-oriented with the objective of the study as well as the interview guide to foster common understanding of the data collection expectations, processes, and goals. The information collected from the pregnancy register, in terms of inclusion criteria, was verified in the field prior to interviews of the study participants. Research assistants from the study team first contacted eligible participants with a phone call and requested participation in in-person interviews. The two research investigators then visited interested study participants at a time and place convenient and acceptable to them. One female investigator interviewed all the female participants, while the male investigator interviewed all the male participants. We conducted the interviews in the interviewees’ homes or other locations based on their choice. All participants gave informed written consent prior to the interviews and were assigned anonymous study participation numbers before the analysis phase. Each interview took approximately 1 h and was recorded with a digital recorder for transcription. In addition to the in-depth interviews, we also collected background information (see Additional file 2). We conducted the interviews until the data produced little or no new useful information in relation to our study objective. The research team held debriefing sessions at the end of each day of data collection to understand the interpretation of collected data, strengths and weaknesses of interview techniques, and any missed opportunities for further exploration, minimize the confusion among the research investigators, and determine when data saturation was reached. In-depth interviews were conducted from May to June 2017.

Data analysis

We prepared an outline of the purpose and plan for data analysis. Throughout the data collection process, we listened to the tape-recorded in-depth interviews, and read through all the transcribed interviews to identify themes that were discussed in the interviews. All interviews were conducted in the Bengali language, transcribed, and then translated into English. Data were indexed and coded manually, organized into a matrix, and then sub-themes and themes were generated according to the components of the HBM [36]. Table 1 shows an example of the thematic analysis process. Data were compared between and within different types of respondents to strengthen the appropriateness of the findings. Two researchers in the team with experience in conducting qualitative research individually coded the data and finalized the code list by checking for similarities and dissimilarities during data interpretation. Discrepancies were discussed between the two researchers first, and then with a third researcher until consensus was reached. We analyzed the data to understand the views of the different target audiences on the underlying factors that influence their ANC utilization.

Message development

Using the results from the in-depth interviews based on HBM constructs, we drafted TCC text messages in English that specifically addressed the knowledge gaps and perceptions that contributed to the low uptake of ANC. We tailored these draft messages to be aligned with specific pregnancy conditions, and the timing of screening for these conditions during ANC to increase client acceptance and enhance the impact on service utilization [37].

Once the general topic for each message was agreed upon by the research team, the format of that message was designed based on our review of effective behavior change techniques (BCT) recommended by Abraham and Michie [38]. We applied established theory and behavior change techniques to the development of draft messages to strengthen the potential of achieving specific behavior change [39, 40]. The messages covered six out of 26 BCTs, underpinned by five theories. BCTs included the provision of general information about behavioral risk, information on benefits and consequences of action or inaction of the behavior, encouraging the person to decide to perform, rewarding the effort toward achieving the behavior change, how to perform the desired health behavior, and planning the desired health behavior with a planned outline to perform (Table 2). The theories linked with the six BCTs are the information-motivation-behavioral skills model (IMB), a theory of reasoned action (TRA), theory of planned behavior (TPB), social-cognitive theory (SCogT) and control theory (CT). We matched each component of a given draft message to a specific BCT. We used positively framed messages as opposed to negatively framed messages to engage in healthy behavior [41]. To address the knowledge gaps identified through the HBM constructs, we included information on common pregnancy complications of anemia, hypertension, and diabetes, their consequences, and the benefits of ANC attendance. To nudge the study participants’ decisions towards healthy behavior, messages were personalized using their name [42, 43]. The content of these draft text messages was translated into the Bengali by the research team.

Two focus group discussions were conducted with pregnant women to get their feedback on the draft messages to ensure that the messages were easily understandable and acceptable. Specifically, participants were shown the content of the messages and asked to comment on their understanding of the message and how to improve the specific text and language. Women were selected from community health workers’ pregnancy registers. The results from the focus group discussions were evaluated by the team and the final Bengali text messages were modified based on the results.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethics and research committees at the International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (protocol number: 16054), and exempt from review by the Regional Ethical Committee in Norway, Southeast region (2017/1018/REK sør-øst C). Individual informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Of a total of 24 in-depth interviewees (Table 3), ten were pregnant women, five were postpartum women, four were mothers-in-law, and five were husbands. All pregnant women were housewives from 18 to 26 years of age. Among the ten pregnant women, four were pregnant for the first time. At the time of the interview, the mean gestational age was 23 weeks and 4 days (8–36 weeks). Seven pregnant women had less than 10 years of education, and the rest had more than 10 years. All the postpartum women were housewives, from 22 to 32 years of age. Three postpartum women had completed less than 10 years of education and two women, more than 10 years. The five husbands ranged from 25 to 41 years of age; four had less than 5 years of formal education, and one up to 10 years.

Perception of pregnancy complications

Perceived susceptibility and severity

Pregnant and postpartum women mentioned some pregnancy complications from their personal experiences. Many of them got information from health care providers. Besides, they also learned from observing the experience of their family members, and others in their neighborhood. In this context, one pregnant woman said, “I have heard that many women face problems. Some suffer a lot during delivery. A girl from our neighborhood delivered her baby at the eighth month, she also suffered from high blood pressure.” (Pregnant woman, para 0).

Women with children mentioned more pregnancy complications compared to women who had never given birth. Complications reported by pregnant and postpartum women included excess vomiting, less fetal movement, anemia, breech presentation, high blood pressure, convulsion, “white discharge”, and fever. Most mothers-in-law mentioned that headache, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, high blood pressure, jaundice, tuberculosis, and pneumonia could develop during pregnancy. The majority of the husbands reported that very few complications could happen in pregnancy, such as vomiting, reduced food intake, abdominal cramp or pain, and edema. One husband stated that “this is a matter of women, and we do not understand the female health (pregnancy-related) problem.” (Husband, CNG driver).

Women were asked to discuss common complications related to pregnancy, and then we focused on three specific complications: anemia, hypertension, and GDM. Most of the postpartum women spontaneously mentioned high blood pressure as a pregnancy complication and convulsion as a consequence. One postpartum woman said, “If the pressure rises, that could create problems. If it’s high, some may have convulsions during pregnancy. I saw someone who had convulsions due to pressure. Then again, low pressure is also bad.” (Postpartum woman, para 4).

On the other hand, only a few pregnant women spontaneously mentioned high blood pressure and convulsion. Most of the husbands and mothers-in-law did not mention high blood pressure and its consequences.

Anemia was rarely mentioned as a perceived pregnancy-related complication by pregnant and postpartum women. One pregnant woman stated after probing, “I have heard that anemia could happen during pregnancy. But, I can’t say what can happen to the mother and baby due to anemia. I have no complete idea.” (Pregnant woman, para 1). Few of the pregnant and postpartum women linked anemia only to blood loss during delivery. They thought that women were less likely to develop anemia at their first pregnancy. Women with previous births could develop anemia in the current pregnancy due to blood loss at their previous delivery. Related to this, one pregnant woman stated, “This is my first pregnancy; I should have plenty of blood in my body.” (Pregnant woman, para 0).

Few husbands stated anemia and weakness as a consequence, while mothers-in-law could not report on anemia at all. Most of the respondents did not mention that diabetes could develop during pregnancy. One postpartum woman stated, “Many pregnant women develop diabetes after delivery … my elder brother’s wife did not have any disease previously, but after delivery of her last child, diabetes was diagnosed.” (Postpartum woman, para 2).

Care for complications

When we asked participants what they would do for any pregnancy-related complications, all stated that they would visit a qualified doctor if they perceived it as an emergency. One postpartum woman stated that pregnant women with anemia should take iron tablets and eat nutritious food. One pregnant woman said that “If I suffer from any problem, I should visit a doctor and (I) need to follow doctor’s advice.” (Pregnant woman, para 2).

Antenatal care practices

The perceived benefit of ANC attendance

Almost all pregnant and postpartum women mentioned that ANC is necessary to know the status of the baby and mother but could not mention the importance of timely ANC as preventive care for appropriate screening and management. ANC was mostly viewed as necessary during pregnancy only if complications developed. In addition, women also thought that the health care provider needs to inform pregnant women about ANC utilization.

One pregnant woman with two children and in her fifth month of pregnancy stated, “I am well now, it is not necessary to go to the healthcare provider now, and they (health care provider) haven’t even called me yet … if any healthcare provider calls me for ANC, I will only go for an ANC visit, but if she (health care provider) doesn’t come to me, I will not go for it. It is her (health care provider’s) duty to inform me to take ANC, not mine.” (Pregnant woman, para 2).

Another postpartum woman stated the benefits of ANC, “The benefits of check-ups are that I could get to know the position of the baby, whether the baby is in the upper or lower abdomen. I could also get to know whether the baby is healthy or not.” (Postpartum woman, para 2).

Mothers-in-law also stated that ANC is needed to know the status of the baby and the mother but could not mention the importance of timely ANC for appropriate screening and management of complications. Similar knowledge was found among husbands, although one of them stated that ANC is important to see the growth of the baby, and to identify problems. Another husband stated that there is no need for ANC during pregnancy. He mentioned, “I don’t think that ANC is important, as my wife did not suffer from any problem, I did not give any importance to ANC. If she suffered from any complication, I would have gone to the doctor with my wife and ask (ed) about the problem” (Husband, cook).

First ANC attendance

The perceived need to attend ANC within the first 5 months of pregnancy was very low among the pregnant women. One pregnant woman at her 4 months of gestational age quoted, “I have a plan to visit the facility for my check-up (ANC) between five to six months (of gestation).” (Pregnant woman, para 0).

Another pregnant woman at the same gestational age said, “No, I don’t need to visit the health facility yet as I am now four months pregnant.” (Pregnant woman, para 1).

Few pregnant women talked about the high chance of miscarriage as the reason behind not seeking ANC at an early stage of pregnancy. The chance of miscarriage within 5 months was believed to be high, and the women thought that ANC does not play any role in preventing miscarriages.

On the other hand, most of the postpartum women had received ANC, and the majority had attended ANC following complications during their pregnancy or f during a previous pregnancy or delivery.

Follow-up ANC visits

Most of the women did not receive information on the timing of follow-up ANC visits from health care providers and did not attend follow-up ANC visits. A few women received follow-up ANC visits, but it was not timely as per the ANC visit schedule. The women reported attending follow-up visits when they faced complications, and in this regard, one pregnant woman said, “I visited a doctor for excess vomiting, and she (doctor) prescribed medicine. But the condition is the same, although I am taking medicine. I am at six months now. Still, I am vomiting. During the first visit, I was told that it would subside gradually. If it happens more frequently, then I have a plan to visit a doctor.” (Pregnant woman, para 2).

Similarly, most of the husbands did not know about the necessity of follow-up ANC visits. Few of them learned about the needs of ANC visits after they became fathers. In this regard, one husband narrated “I have a child, if I did not have a child, I would not have known about the check-ups. After three months and up to delivery, we need to go monthly for check-ups.” (Husband, CNG driver).

Perceived barriers to ANC attendance

Pregnant women who did not attend care reported a wide range of reasons, including lack of decision-making power, distance to the facility, being too busy, not being satisfied with the treatment by health care providers, non-cooperation by their husband, and unavailability of any family member to help in the household. Regarding the non-cooperation by a husband, one woman quoted, “I had bleeding yesterday, and I cried a lot. I knew a little bit about what I should do for this. But I was unable to do anything (she was pointing to her husband through a non-verbal expression that her husband did not take her to the doctor while she was bleeding). If I can’t go to the doctor now, if I continue bleeding, it would be harmful to my baby and for me as well. But I cannot do anything.” (Pregnant woman, para 2).

Self-care knowledge, practice, and family cooperation during pregnancy

Self-care and family support

We further explored women’s general attitudes to taking care of their pregnancy through self-care and their families’ supportiveness of her pregnancy and care. The majority of women practiced healthy behaviors such as eating adequate nutritious diets, avoiding heavy work, and resting. Most mothers-in-law and husbands knew that pregnant women need to eat nutritious food, take proper rest, and avoid lifting heavy things. Very few first-time pregnant women mentioned dietary restrictions such as avoiding selected fish and green coconut during pregnancy.

Most of the women living with extended families received household support from their family members, especially from mothers-in-law. “My mother-in-law brings water from outside, sweeps the room, and helps me to cut the vegetables. I do all the cooking and other work.” (Pregnant woman, para 2). Women living in single-family households generally did not get support for their household work. One pregnant woman living in a single-family household reported, “I am the only female in the household. I have two small children. I need to do some heavy work, I bring water for cooking and washing clothes myself.” (Pregnant woman, para 2).

Decision making for maternal care service utilization

When the pregnant and postpartum women were asked about the decision-maker for their health care service utilization, most of them mentioned that their husbands were the main decision-makers in the family. But nulliparous women reported that their mothers-in-law played a vital role in the decision making along with their husbands. One pregnant woman stated, “I became pregnant for the first time. I don’t know much about pregnancy. So, most of the decisions are taken by my mother-in-law and husband.” (Pregnant woman, para 1).

All mothers-in-law with currently pregnant daughters-in-law mentioned that she and her son jointly made critical decisions about the pregnancy-related care in the family. On the other hand, most husbands said that they were the main decision-maker in the family. In this context, one husband cited, “I will have to make the decision. I cannot depend on anybody. Now I am here; I will make the decision.” (Husband, migrant worker).

Targeted client communication strategy

Modes of contact and reminders

Pregnant women were asked about communication strategies that could increase ANC attendance. Almost everyone preferred direct phone calls to remind them of ANC dates and give them health information. In favor of phone calls, one woman stated, “Through a phone call, I would be able to talk directly. In the case of messages, I would have to read the message to understand. Sometimes I read (the) message, sometimes not, if I am not busy with any work. That’s why phone calls would be good.” (Pregnant woman, primipara). Another woman stated, “If there is an emergency and the phone rings, I would pick it up and listen to that. After that, the phone remains somewhere idle; the message would only make a small sound, nothing after that.” (Postpartum woman, para 3). However, most of the participants mentioned that text messages could work as a reminder for the ANC schedule.

Contact person and time for communication

Given that husbands and mothers-in-law were the decision-makers, we asked to whom and when to send the text messages related to ANC attendance and pregnancy complications. Most women owned a mobile phone and suggested that they preferred direct communication with the pregnant woman. Very few women did not own mobile phones and suggested communicating with their husbands and mother-in-laws. Although some said the text messages could be sent at any time, others suggested that evenings would be better.

Development of SMS messages for TCC

The following main findings from our study guided the development of SMS messages for TCC. First, women and families only perceive the need for early ANC when women are sick. Perceived susceptibility to common pregnancy complications, and the knowledge that they may occur without symptoms, was low among study participants. Second, women did not recognize that common pregnancy complications could necessitate care during pregnancy. Third, they did not know that attending ANC could result in fewer complications or earlier detection of complications. Fourth, they were unaware of the appropriate number and timing of ANC visits. Finally, most of the women who received detailed information on when and where to attend follow-up ANC during their first ANC visit did attend those follow-up visits, suggesting that lack of information is a key factor leading to inadequate utilization of ANC and that basic information served as cues-to-action. The evidence did not suggest any specific modifiable factor which could address a majority of women’s self-efficacy and ability to attend ANC.

Given this evidence, and the planned integration of automated data-driven SMS messages into the eRegistry, we designed a series of text messages for women to act as cues-to-action and target women’s knowledge about ANC, specifically on 1) the benefits of attending ANC; 2) women’s susceptibility to complications; and 3) the severity of complications. The messages were designed to match the timing of critical screenings for common conditions such as anemia, hypertension, and GDM. We used clinical data from the eRegistry to further tailor these messages, based on women’s gestational age and common risk factors for the medical conditions targeted (Table 4), in order to make the text messages more individualized and provide added value to the individual woman.

The Bangladeshi government recommends a schedule of four ANC visits for low-risk pregnant women. Reminder messages were designed to be sent 1 week and 1 day prior to the scheduled ANC date; we selected one topic to be highlighted in each of the reminder messages (Table 5). In addition, we created a welcome message to be sent upon enrolment, referral facilitation messages, and facility delivery reminders. The referral facilitation messages were reminders to women that their provider had recorded danger signs or created a referral in the eRegistry.

Given that the messages would be automatically generated within the eRegistry, we were able to additionally tailor each message based on clinical characteristics. Specifically, if data were entered into the eRegistry indicating anemia, hypertension, or gestational diabetes, an algorithm was developed which would take that into consideration and appropriately modify the messages. And, if the risk factors for these conditions were documented in the eRegistry (as shown in Table 4), the text messages would be tailored further.

The initial draft of the TCC messages, based on the HBM and the ANC schedule, and tailored with the behavior change techniques, were translated into Bengali from English and shared with pregnant women in focus group discussions (data not shown). Participants reported that the content of messages was adequate, but some modifications of terminology were needed for ease of understanding. We then reviewed each message and finalized the wording. Each message was adapted to the typical SMS character limits (knowing that for some messages up to three SMS could be sent). In the end, a library of 43 TCC messages was developed based on whether the individual woman had anemia, hypertension, GDM, and associated risk factors in the eRegistry. Examples of the messages are included in Table 6.

Discussion

The study found that most of the participants could not describe ANC as a preventive form of care. It was viewed as necessary during pregnancy only if complications developed, while the WHO recommends preventive ANC for early identification of complications [5]. We found that most women would only attend ANC after 5 months of pregnancy due to concerns about miscarriages. They would seek care regardless of their gestational age if complications arise. In general, the population had limited knowledge of ANC, pregnancy complications, and the consequences for the mothers and their neonates. Limited ANC attendance has been shown to result in poor pregnancy outcomes [61,62,63]. The utilization of ANC was low, and women did not receive ANC services at the recommended time. Similar to other reports from Bangladesh, only a small proportion of women in our study received their first ANC visit within 16 weeks of gestation [9]. Most pregnant and postpartum women mentioned that ANC is required only to know the wellbeing of the baby and the mother. Women also reported not having adequate information on the timing and number of ANC visits needed in our study. A cross-sectional study found similar results and observed low levels of awareness about ANC among pregnant women in a rural area, and recommended development and strengthening of behavior change communication [64].

Poor understanding of complications, combined with the lack of contextual health education, might lead to less timely attendance at ANC. Similar to our findings, another study in Matlab, Bangladesh, reported that only 26% of women had good knowledge of pregnancy complications [18]. Several studies have shown that ANC utilization is associated with women’s knowledge about pregnancy complications [18, 65, 66]. Women with poor knowledge of pregnancy complications are also likely to be unfamiliar with the consequences of the conditions. Awareness of the benefits of ANC is positively associated with maternal and neonatal outcomes [67]. However, we know that knowledge alone without adequate access, affordable costs, and community support will not improve utilization.

Lack of decision-making power of women for using maternal and child health care may also contribute to low ANC utilization in Bangladesh. Women need to be empowered with adequate health information, availability, and use of services to make their own decisions regarding healthcare through different strategies [68, 69]. Although husbands and mothers-in-law are the primary decision-makers in the household and make the majority of decisions about health service utilization during pregnancy and delivery, researchers perceived that their knowledge of pregnancy complications was limited. Creating awareness among husbands and mothers-in-law using health education in simple language can potentially improve maternal and neonatal service utilization [70]. Although health information is essential for women’s empowerment, adequate support in terms of availability of and access to services and additional structural factors relating to household decision-makers are needed in addition to achieve the goal.

The prevalence of mild to moderate anemia during pregnancy is about 50% in rural Bangladesh, and early diagnosis and management can prevent serious consequences for the health of the mother and the baby [71]. The inadequate knowledge of anemia during pregnancy demonstrated by the participants in our study is similar to the other studies conducted in low-and-middle-income countries [72, 73]. Lack of knowledge on anemia could be one reason for the high prevalence of anemia in Bangladesh. Our finding of poor knowledge of GDM is aligned with studies conducted in Bangladesh and other low-and-middle-income countries [74, 75]. Compared to diabetes and anemia, knowledge of hypertension was better, especially among postpartum women, presumably because some had developed hypertension during their pregnancy. A study conducted in Bangladesh assessing community awareness, beliefs, and experiences around hypertension found a lack of knowledge of hypertension [76]. This low level of knowledge about anemia, hypertension, and diabetes implies that effective health education could improve adequate knowledge, thereby increasing ANC utilization among pregnant women.

Although studies have reported that text message interventions can increase ANC utilization [25], knowledge of women’s reading skills, access to mobile phones, and willingness to receive SMS are all essential to appropriately tailor these messages and increase uptake of ANC. Our study found that most pregnant and postpartum women owned mobile phones and were educated beyond the primary level. Though women expressed their willingness to receive SMS in our study, their age and current practice of mobile phone usage might ultimately influence ANC utilization.

The study has some limitations. Perceived knowledge of ANC care might be different in other parts of Bangladesh due to differences in context. Another weakness might be the challenges that the study participants might have faced in putting their experiences, meanings, and emotions into words. Qualitative methods alone may not be adequate for understanding the magnitude of the problem. We could not explore other factors that might influence their knowledge and practices, such as participants’ exposure to mass media and their social capital. We did not cover a wider range of participants such as health care providers, health managers, local elite, and policy makers that might have contributed to more comprehensive insight.

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study in Bangladesh aiming to develop TCC via text messages based on community perceptions for the purpose of increasing ANC utilization. The study shows the critical need to evaluate the local beliefs and belief structures when developing any form of client communication, especially when it will be delivered through an intermediary, such as a digital device. Key strengths of the study design and the development of TCC include having the researchers involved in all steps towards the final cluster-randomized trial of the comprehensive eRegistry, to ensure that the messages are well-integrated within the larger health systems platform. To enhance the appropriateness of the data analysis, we checked transcripts against audio recordings, and performed triangulation among codes and themes by consensus. We placed special emphasis on confidentiality, particularly important in this context where we were linking clinical records with text messages that could be read by anyone that has access to the phone. As an example, recipients’ specific risk factors were excluded from the text messages, considering that a woman might share her mobile phone with other family members. With due consideration to the cultural context, we decided to send the TCC messages 1 week prior to scheduled visits and a second reminder message 24 h before the visit to empower women for future planning and to react quickly if necessary. The output of this study is a critical component to the eRegMat trial, which is, in part, aimed at assessing the effectiveness of these automated TCC messages to increase ANC utilization. This study’s findings are relevant for any implementations of digital health interventions to increase ANC coverage and can serve as a model for a theoretically informed approach to TCC.

Conclusion

This study presents an example of TCC message development based on systematically evaluated gaps in knowledge, awareness of pregnancy care and complications, established theory, and behavior change techniques with the purpose of increasing ANC utilization. Improving knowledge of pregnancy complications and the importance of timely ANC is essential, and providing health information through text messages has the potential to raise awareness among pregnant women. A text message intervention is feasible in this Bangladeshi population as most women and households have access to mobile phones. The effectiveness of these TCC messages is being evaluated in an ongoing cluster-randomized controlled eRegMat trial (trial registration no: ISRCTN69491836).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and materials used in the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- TCC:

-

Targeted client communication

- SMS:

-

Short Message Service

- MMS:

-

Multimedia Message Service

- eRegMat:

-

Electronic registry Matlab

- DHIS2:

-

District Health Information System 2

- HBM:

-

Health Belief Model

- CC:

-

Community Clinic

- UH&FWC:

-

Union Health and Family Welfare Centres

- DM:

-

Diabetes Mellitus

- BCT:

-

Behavior change technique

- IMB:

-

Information-motivation-behavioral skills model

- TRA:

-

Theory of reasoned action

- TPB:

-

Theory of planned behavior

- SCogT:

-

Social-cognitive theory

- CT:

-

Control theory

References

Tuncalp O, Pena-Rosas JP, Lawrie T, Bucagu M, Oladapo OT, Portela A, et al. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience-going beyond survival. BJOG. 2017;124(6):860–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14599.

Shahjahan M, Chowdhury HA, Akter J, Afroz A, Rahman MM, Hafez M. Factors associated with use of antenatal care services in a rural area of Bangladesh. South East Asia J Public Health. 2013;2(2):61–6. https://doi.org/10.3329/seajph.v2i2.15956.

Lassi ZS, Kumar R, Mansoor T, Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Essential interventions: implementation strategies and proposed packages of care. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):S5.

Rahman MH, Mosley WH, Ahmed S, Akhter HH. Does service accessibility reduce socioeconomic differentials in maternity care seeking? Evidence from rural Bangladesh. J Biosoc Sci. 2008;40(1):19–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932007002258.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva; 2016. [https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1]. Accessed 16 Jan 2020.

Kishowar Hossain AH. Utilization of antenatal care services in Bangladesh: an analysis of levels, patterns, and trends from 1993 to 2007. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(4):395–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539510366177.

WHO. Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth, Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A guide for essential practice 2015. [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249580/9789241549356-eng.pdf?sequence=1. Acessed 01 Feb 2020.

UNICEF. Antenatal care. 2020. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/.

National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) aI. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18: key Indicators Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, and ICF.2019 [Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR104/PR104.pdf].

Ahmed S, Khan MM. Is demand-side financing equity enhancing? Lessons from a maternal health voucher scheme in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1704–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.031.

Edie GE, Obinchemti TE, Tamufor EN, Njie MM, Njamen TN, Achidi EA. Perceptions of antenatal care services by pregnant women attending government health centres in the Buea Health District, Cameroon: a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:45.

Warri D, George A. Perceptions of pregnant women of reasons for late initiation of antenatal care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2746-0.

Al-Ateeq MA, Al-Rusaiess AA. Health education during antenatal care: the need for more. Int J Women's Health. 2015;7:239–42. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S75164.

WHO. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. 2016.

Bitew Y, Awoke W, Chekol S. Birth preparedness and complication readiness practice and associated factors among pregnant women, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Sch Res Notices. 2016;2016:8727365.

Bogale D, Markos D. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs among child bearing age women in Goba district, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:77.

Moran AC, Sangli G, Dineen R, Rawlins B, Yameogo M, Baya B. Birth-preparedness for maternal health: findings from Koupela District, Burkina Faso. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):489–97.

Pervin J, Nu UT, Rahman AMQ, Rahman M, Uddin B, Razzaque A, et al. Level and determinants of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women: a cross sectional study in a rural area in Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209076.

Hyder SM, Persson LA, Chowdhury M, Lonnerdal BO, Ekstrom EC. Anaemia and iron deficiency during pregnancy in rural Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(8):1065–70. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004645.

Hinkosa L, Tamene A, Gebeyehu N. Risk factors associated with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy in Nekemte referral hospital, from July 2015 to June 2017, Ethiopia: case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2693-9.

Hajera Mahtab BB. Gestational diabetes mellitus – global and Bangladesh perspectives. Austin J Endocrinol Diabetes. 2016;3(2):1041.

Anderson AD, Lichorad A. Hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus, and anemia: three common medical complications of pregnancy. Prim Care. 2000;27(1):185–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0095-4543(05)70155-X.

Bogale B, Mørkrid K, O’Donnell B, Ghanem B, Ward I, Khader K, et al. Development of a targeted client communication intervention to women using an electronic maternal and child health registry: a qualitative study. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-1002-x.

WHO. Classification of digital health interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260480/WHO-RHR-18.06-eng.pdf?sequence=1]

Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040.

Rowntree O, Shanahan M. Connected women: the mobile gender gap report; 2020.

Bäck L, Mäkelä K. Mobile phone messaging in health care—where are we now? J Inform Tech Soft Eng. 2012;2:1–6.

Brinkel J, May J, Krumkamp R, Lamshoft M, Kreuels B, Owusu-Dabo E, et al. Mobile phone-based interactive voice response as a tool for improving access to healthcare in remote areas in Ghana - an evaluation of user experiences. Tropical Med Int Health. 2017;22(5):622–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12864.

Crawford J, Larsen-Cooper E, Jezman Z, Cunningham SC, Bancroft E. SMS versus voice messaging to deliver MNCH communication in rural Malawi: assessment of delivery success and user experience. Glob Health: Sci Pract. 2014;2(1):35–46.

Car J, Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11(7):CD007458.

Junod Perron N, Dao MD, Righini NC, Humair JP, Broers B, Narring F, et al. Text-messaging versus telephone reminders to reduce missed appointments in an academic primary care clinic: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):125. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-125.

Abraham C, Sheeran P. The health belief model. Cambridge Handbook Psychol Health Med. 2005;2:97–102.

Islam A, Biswas T. Health system in Bangladesh: challenges and opportunities. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(6):366. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajhr.20140206.18.

NIPORT. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014. Dhaka and Calverton: National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and Macro International; 2014.

Tabassum M, Begum N, Shohel M, Faruk M, Miah M. Factors influencing Women's empowerment in Bangladesh. Sci Technol Public Policy. 2019;3(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.stpp.20190301.11.

Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Thematic analysis; 2012.

Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):454–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn004.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):379–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379.

Cadilhac DA, Busingye D, Li JC, Andrew NE, Kilkenny MF, Thrift AG, et al. Development of an electronic health message system to support recovery after stroke: inspiring virtual enabled resources following vascular events (iVERVE). Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1213–24. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S154581.

Redfern J, Thiagalingam A, Jan S, Whittaker R, Hackett ML, Mooney J, et al. Development of a set of mobile phone text messages designed for prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(4):492–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487312449416.

Updegraff J, Brick C, Emanuel A, Mintzer R, Sherman D. Message framing for health: moderation by perceived susceptibility and motivational orientation in a diverse sample of Americans. Health Psychol. 2015;34(1):20–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000101.

Perry C, Chhatralia K, Damesick D, Hobden S, Volpe L. Behavioural insights in health care nudging to reduce inefficiency and waste; 2015.

Masthoff J, Grasso F, Ham J. Preface to the special issue on personalization and behavior change. User Model User-Adap Inter. 2014;24(5):345–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-014-9151-1.

Kahsay HB, Gashe FE, Ayele WM. Risk factors for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy among mothers in Tigray region, Ethiopia: matched case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):482. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2106-5.

Lee KW, Ching SM, Ramachandran V, Yee A, Hoo FK, Chia YC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):494. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2131-4.

Agrawal S, Singh A. Obesity or underweight-what is worse in pregnancy? J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66(6):448–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0735-4.

Gedefaw L, Ayele A, Asres Y, Mossie A. Anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in Wolayita Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25(2):155–62. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v25i2.8.

Alfadhli EM, Osman EN, Basri TH, Mansuri NS, Youssef MH, Assaaedi SA, et al. Gestational diabetes among Saudi women: prevalence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Ann Saudi Med. 2015;35(3):222–30. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2015.222.

Al-Farsi YM, Brooks DR, Werler MM, Cabral HJ, Al-Shafei MA, Wallenburg HC. Effect of high parity on occurrence of anemia in pregnancy: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:7.

Desalegn S. Prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy in Jima town, southwestern Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 1993;31(4):251–8.

Tebeu PM, Foumane P, Mbu R, Fosso G, Biyaga PT, Fomulu JN. Risk factors for hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: a report from the Maroua regional hospital, Cameroon. J Reprod Infertil. 2011;12(3):227–34.

Al J, Grandmultiparity A. Potential risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Reprod Med. 2012;57(1-2):53–7.

Allen VM, Joseph KS, Murphy KE, Magee LA, Ohlsson A. The effect of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy on small for gestational age and stillbirth: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-4-17.

Teixeira MP, Queiroga TP, Mesquita MD. Frequency and risk factors for the birth of small-for-gestational-age newborns in a public maternity hospital. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2016;14(3):317–23. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082016AO3684.

Brahmanandan M, Murukesan L, Nambisan B, Salmabeevi S. Risk factors for perinatal mortality: a case control study from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Int J Reprod, Contracept, Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6:2452.

Endeshaw G, Berhan Y. Perinatal outcome in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Int Sch Res Notices. 2015;2015:208043.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Union Health and Family Welfare Centre guideline. 2014.

Hossain S. Community based skilled birth attendant training curriculum; 2010.

Kautzky-Willer A, Harreiter J, Bancher-Todesca D, Berger A, Repa A, Lechleitner M, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128(Suppl 2):S103–12.

Rani PR, Begum J. Screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus, where do we stand. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(4):Qe01–4.

Blondel B, Marshall B. Poor antenatal care in 20 French districts: risk factors and pregnancy outcome. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(8):501–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.52.8.501.

Pervin J, Moran A, Rahman M, Razzaque A, Sibley L, Streatfield PK, et al. Association of antenatal care with facility delivery and perinatal survival – a population-based study in Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-111.

Vogel JP, Habib NA, Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Dowswell T, Carroli G, et al. Antenatal care packages with reduced visits and perinatal mortality: a secondary analysis of the WHO antenatal care trial. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-19.

Hossain S, Haque M, Bhuiyan R, Tripura N, Masud JHB, Aziz I. Awareness of pregnant women regarding pregnancy and safe delivery in selected rural area. Chattagram Maa-O-Shishu Hosp Med Coll J. 2014;13(2):28–31.

Deo KK, Paudel YR, Khatri RB, Bhaskar RK, Paudel R, Mehata S, et al. Barriers to utilization of antenatal care services in Eastern Nepal. Front Public Health. 2015;3:197.

Tesfaye G, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Application of the Andersen-Newman model of health care utilization to understand antenatal care use in Kersa District, Eastern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208729.

Khatun M, Khatun S. Maternal ‘awareness of antenatal care on impact of mothers’ and newborn health in Bangladesh. Open J Nurs. 2018;08(01):102–13. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2018.81009.

Noordam AC, Kuepper BM, Stekelenburg J, Milen A. Improvement of maternal health services through the use of mobile phones. Tropical Med Int Health. 2011;16(5):622–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02747.x.

Khanum PA, Islam A, Quaiyum MA, Millsap J. Use of obstetric care services in Bangladesh: does knowledge of husbands matter? 2002.

Islam S, Perkins J, Siddique MAB, Mazumder T, Haider MR, Rahman MM, et al. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women and couples and its association with skilled birth attendance in rural Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197693.

Bashar M, Haque AKM, Rahman R. Prevalence of Anaemia among pregnant women in a rural area of Bangladesh: impact of socio-economic factors. Food Intake Micronutr Supplementation. 2020;2:1–7.

Appiah PK, Nkuah D, Bonchel DA. Knowledge of and adherence to Anaemia prevention strategies among pregnant women attending antenatal care facilities in Juaboso district in Western-north region, Ghana. J Pregnancy. 2020;2020:2139892.

Sultana F, Ara G, Akbar T, Sultana R. Knowledge about Anemia among pregnant women in tertiary hospital. Med Today. 2019;31(2):105–10.

Lakshmi D, Felix AJW, Devi R, Manobharathi M. Study on knowledge about gestational diabetes mellitus and its risk factors among antenatal mothers attending care, urban Chidambaram. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2018;5(10):4388–92.

Monir N, Zeba Z, Rahman A. Comparison of knowledge of women with gestational diabetes mellitus and healthy pregnant women attending at hospital in Bangladesh. J Sci Found. 2018;16(1):20–6. https://doi.org/10.3329/jsf.v16i1.38175.

Kanij S, Nur R, Hossain S. 38 Community perceptions of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, health-seeking behaviors and pathways to seeking care in bangladesh: Preeclampsia in low and middle income countries. Pregnancy Hypertens: An Int J Women’s Cardiovasc Health. 2016;6(3):196.

Acknowledgments

We would like to forward our gratitude to all the respondents who participated in this study.

Funding

This research study was funded by the Research Council of Norway, Global Health and Vaccination Research (GLOBVAC), grant number: 248073, and the Centre for Intervention Science in Maternal and Child Health (CISMAC; award number 223269), which was funded by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence scheme and the University of Bergen (UiB), Norway. icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of GLOBVAC’s research efforts. Icddr,b is also grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden, and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support. The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JFF, IKF, and AR contributed to the study concept and design. IKF and JP supervised the implementation of the study. JP, BKS, UTN, and AMQ involved in data collection. JP, BKS, UTN, FK, MV, JFF, and IKF contributed to data analyses. JP and IKF drafted the initial draft of the manuscript. JP, BKS, UTN, FK, AMQ, MV, AR, JFF, and IKF reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research and Ethical Review Committees of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, and the Regional Ethical Committee in Norway, Southeast region. All participants received an explanation of the purpose of the study and gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

In-depth interview guides.

Additional file 2.

Background information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pervin, J., Sarker, B.K., Nu, U.T. et al. Developing targeted client communication messages to pregnant women in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 21, 759 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10811-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10811-y