Abstract

Background

Young adults who were suspended from school during adolescence are more likely than matched non-suspended youth to be arrested, on probation, or not graduate from high school, which are STI risk factors. This study evaluates whether suspension is a marker for STI risk among young adults who avoid subsequent negative effects.

Methods

This study evaluated whether suspension predicts a positive test for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomoniasis in a urine sample using matched sampling in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health (Add Health), and evaluated potential mediators between suspension and STI status using causal mediation analysis. We used Mahalanobis and exact matched sampling within propensity score calipers to compare 381 youth suspended for the first time in a 1-year period with 980 non-suspended youth. The suspended and non-suspended youth were similar on 67 pre-suspension variables. We evaluated STI outcomes 5 years after suspension.

Results

Before matching, suspended youth were more likely to test positive for trichomoniasis and gonorrhea, but not chlamydia, than non-suspended youth. Suspended youth were more likely to test positive for trichomoniasis 5 years after suspension than matched non-suspended youth (OR = 2.87 (1.40, 5.99)). Below-median household income before suspension explained 9% of the suspension-trichomoniasis association (p = 0.02), but criminal justice involvement and educational attainment were not statistically significantly mediators.

Conclusions

School suspension is a marker for STI risk. Punishing adolescents for initial deviance may cause them to associate with riskier sexual networks even if they graduate high school and avoid criminal justice system involvement. Suspension may compound disadvantages for youth from below-median-income families, who have fewer resources for recovering from setbacks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Summary

Adolescents who were suspended from school for the first time had greater trichomoniasis risk than non-suspended adolescents propensity-matched on 67 covariates, and the association was mediated by below-median family income.

Background

The persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) raise questions of which racially disparate social structures contribute to these disparities. Racial disparities in STIs seem to be related to network effects, rather than riskier individual sexual behavior [1]. Education has been recognized as a social determinant of health [2], and school suspension appears to be the largest factor in the black-white gap in high school graduation [3]. However, it’s unknown whether school suspension predicts STIs. This study evaluates whether youth who are suspended from school for the first time are more likely to test positive for chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and gonorrhea 5 years after first suspension than similar youth who had never been suspended, and uses causal mediation to evaluate the roles of household income during adolescence. This study uses tests for chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and gonorrhea as objectively assessed potential health effects of suspension to avoid potential differential reporting, as would be the case for a self-reported health effect.

Implemented during the peak of school violence in the mid-1990s, the federal Gun-Free Schools Act mandated school suspension for weapons and illegal drugs; subsequently, states and localities mandated school suspension for non-violent and subjective offenses [4]. The most recent nationally representative estimates of the lifetime incidence of school suspension over grades K-12 are 44% for males (67% of Black males) and 25% of females (44% of Black females) [5]. Black youth appear to be suspended more than non-Black youth due to racial discrimination: psychology experiments with vignettes have found that educators are more likely to suspend Black youth than White youth [6].

Adolescents often experiment with risk behavior, but the theory of labeling suggests that punishing this experimentation with school suspension may cause youth to be labeled, stigmatized, join risky social networks, and subsequently engage in riskier behavior [7,8,9], as have been found in studies of police stops and arrests [10, 11]. Suspended youth may also engage in deviance amplification with both health and non-health behaviors: suspended youth are more likely to smoke tobacco [12], use marijuana [13], and engage in antisocial behavior [14] in the year after suspension than youth who were not suspended. However, these results may be explained by selection bias: suspended youth may have engaged in risk behavior even if they were not suspended. One study found no difference in educational attainment two years after suspension and inferred that previous studies could be explained by selection bias [15]. However, a longitudinal study that used matched sampling found suspended youth have lower educational attainment and greater criminal justice involvement than matched non-suspended youth 12 years after school suspension [16].

Education, race, and economic disadvantage are all associated with biomarker-detected STIs. Four-year college degrees (versus some or no college) are protective among women [17]; two-year college degrees (versus current enrolment in two-year college) are protective among young adults [18]; and men in the National Job Training Program have below-average educational attainment and greater chlamydia prevalence than men in nationally representative samples [19]. However, racial disparities are more pronounced than educational disparities; Black female college graduates have higher assay-determined STI risk than White females without a high school diploma [20]. Economic disadvantage is also a risk factor for STIs. Adolescents’ household income quintile predicts their risk of STIs 6 years later, at ages 18–25 [21]. This study uses nearest-neighbor Mahalanobis and exact matching within propensity score calipers to evaluate whether youth who were suspended for the first time during a one-year period were more likely to test positive for STIs 5 years later than matched non-suspended youth not suspended during that period. This study is novel for using a statistical matching method to minimize potential confounding and selection bias, and causal mediation analysis to evaluate potential pathways between suspension and STIs.

Methods

Data

We evaluate the association between school suspension and STIs using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health (Add Health), which remains the only nationally representative longitudinal study in the United States with STI test results. Add Health comprises a nationally representative sample of adolescents attending public and private high schools and their feeder middle schools in 1994–95 who were interviewed in their homes in 1995 (wave 1, response rate 79.0%), 1996 (wave 2, response rate 88.6%), and 2001 (wave 3, response rate 77.4%). We also used data from interviews with participants’ parents (93% female parents) in 1995 (response rate 82.5%) and school administrators in 1995 (response rate 97.7%.) [22]

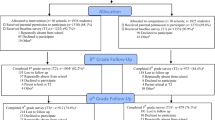

We used data from 7748 respondents who participated in waves 1, 2, and 3 who reported that they had never received an out-of-school suspension (“Have you ever received an out-of-school suspension from school?”) or been expelled from school (“Have you ever been expelled from school?”); reported their birthdate and household size at baseline; and gave a urine sample for the STI tests. Respondents who gave a urine sample for STI testing received an extra $10 incentive; 91.5% of unmarried high school graduates gave a sample. Fig. 1 shows the construction of the sample and matched sample. We did not use the survey weights, because they were developed for the entire sample; developing new weights for a highly constrained sub-sample could induce bias [23].

Predictor: new suspension in 1995–96

We measured a first school suspension between 1995 and 1996 from an affirmative answer to the wave 2 question, “During this school year (during the 1995–96 school year) did you receive an out-of-school suspension from school?” Because the sample was limited to participants without a prior out-of-school suspension or expulsion (see previous section), a suspension reported at wave 2 represents is a first lifetime suspension.

Outcomes: positive STI tests

Three STI outcomes were measured in 2001, 5 years after suspension: testing positive for Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea), or Trichomonas vaginalis (trichomoniasis). STI tests that did not return results (357 chlamydia, 810 gonorrhea, and 413 trichomoniasis) were coded as missing, so the sample sizes are slightly different for each STI.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening used Ligase Chain Reaction amplification technology in the Abbot LCx Probe System. Trichomoniasis was detected with a PCR-ELISA test for Trichomonas vaginalis DNA which has a sensitivity of 91% in women compared with combined reference standard of wet mount and culture from vaginal swab and 89% in men compared with urethral swab culture, and an adjusted specificity of 93% in women and 95% in men [24]. Chlamydia and gonorrhea tests were FDA-approved, but the trichomoniasis test was not yet FDA-approved, so only chlamydia and gonorrhea test results were made available to participants.

Control variables

We identified 67 potential confounders of the relationship between suspension and STIs using Gottfredson and Hirschi’s self-control theory of deviance (3 s) and from past research about suspension [5, 25], educational attainment [26], and arrest [27], including demographics, socioeconomic status, sexual risk-taking, relationships with adults, educational factors, parents’ risk behavior, substance use, personality and mental health, and deviance. The control variables are listed in full in Appendix.

The control variables were measured at baseline, except for father ever in prison, which was measured in 2001. Father-in-prison measurement was used as a control variable because it was not likely to be a consequence of their child’s school suspension. The father could have gone to prison after the child’s school suspension, but the father’s propensity to go to prison likely existed prior to the child’s school suspension.

Negative control

Randomized laboratory experiments routinely include a negative control: a condition under which a null result is expected; if a negative control condition does not produce a null result, that suggests a problem with the experiment. The propensity matching approach used in this paper mimics a randomized experiment; in this case, we use a negative control to detect residual confounding after matching [28]. We used post-suspension impulsivity, measured in 2001, as a negative control because we do not expect post-suspension impulsivity to be greater in suspended than matched non-suspended youth. Impulsivity was the sum of nine Likert-type scale items on a scale from 0 to 1 (α = .94). After matching, suspended and non-suspended youth did not differ on baseline constructs in the Gottfredson-Hirschi self-control model, including systematic versus gut-feeling decision-making [29] The same 9-item impulsivity scale was not available at baseline, so it could not be used for matching.

Data analysis

We conducted analyses in the R statistical package 3.5.1.

Bivariate analysis

We identified variables that differed between suspended and non-suspended youth using standardized differences, a measure of effect size defined as the difference in means divided by the standard deviation. The goal of propensity matching methods is to reduce standardized differences to below 0.2, but ideally below 0.1.

Propensity matching method

We used a propensity matching method to identify non-suspended youth that are similar to suspended youth on the control variables to minimize potential selection bias, using the R MatchIt library [30]: the specific matching method used is called 3:1 exact and nearest-neighbor Mahalanobis matching with replacement, within propensity score calipers of 0.25 standard deviations. The procedure used for matching described in the next two paragraphs will elucidate the meaning of each term in the name of the specific matching method. The matching method identified suspended and non-suspended youth that had similar values of the 67 potential confounders and the estimated propensity score. The estimated propensity score for each participant is the predicted probability that the individual will be suspended: the fitted value of a logistic regression with the outcome of suspension. The predictors in the logistic regression are specified in the below procedure, but it is important to note that the matching procedure can balance on the 67 potential confounders even though only a subset of the 67 variables are included in the propensity score.

The term “3:1 matching” means that we matched 3 non-suspended youth to each suspended youth using the following procedure. The term “exact matching” means that for each suspended youth, exact matching reduced the set of eligible non-suspended youth by requiring that only non-suspended youth with the same daily smoking status and ever-marijuana status could be considered. The term “within propensity score calipers of 0.25 standard deviations” means that we reduced the set of eligible non-suspended youth further to those within 0.25 standard deviations of the estimated propensity score; that is, these non-suspended youth had similar predicted probabilities of suspension. Finally, the term “nearest-neighbor Mahalanobis matching” means that we identified the 3 closest youth according to a correlation-adjusted distance measure of age in years (not rounded) and grade point average; the correlation-adjusted distance measure is named for the statistician Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis.

We estimated the propensity for each individual to be suspended using a logistic regression with the outcome of a first suspension between 1995 and 96 and predictors of demographic factors (rural residence, Northeast region, lives with both biological parents, male gender, age, born in US, Latino, Asian, and Black race/ethnicity, home language is English); socioeconomic status (SES) (mother high school graduate, mother college graduate, parent is currently employed, per capita household in- come, parent reports enough money to pay bills, father ever in prison [2001]), health and risk behavior factors (experiences with violence, delinquency score, respondent smokes daily, household member smokes, mother smokes, depression score, positive expectancies), educational factors (standardized test score, school attachment, expect to attend college, attend private vs. public school, school is strict on civil order, school is strict on substance use, never truant), and personality factors (parent’s assessment of their child, agreeableness, emotional stability, parental closeness, systematic vs. gut-feeling decision making).

Statistical analysis within the matched sample

STIs were rare outcomes, so we used logistic regression to predict chlamydia and trichomoniasis in the unmatched and matched samples, controlling for baseline age, race/ethnicity, gender, and household income tertiles [21]. Gonorrhea was rare, with only 21 cases, so we only estimated crude odds ratios, not adjusted odds ratios. Using control variables measured at baseline avoids bias towards the null from using factors that were intermediate between suspension and STIs [31].

We used causal mediation analysis to evaluate whether pre-treatment and post-treatment variables mediated the relationship between suspension and STIs [32]. This study evaluated 34 post-suspension variables for mediation: marriage; educational attainment and predictors of educational attainment (e.g., full-time college attendance, community versus four year college matriculation, enrollment gap prior to matriculation); criminal justice outcomes (ever arrested, convicted as adult, arrested as minor, convicted as minor); sexual orientation (identify as lesbian/gay/bisexual (LGB), publicly open as LGB); employment status (full-time, day shift); substance use (ever smoker, current smoker, binge drinking); sexual risk behavior (partner has STI, frequency of sex in the past year, number of partners in past year, number of partner in lifetime, condom use frequency); personality (impulsivity, self-esteem); and expulsion.

We used sensitivity analysis for multiple controls to assess whether observed differences could be attributed to unobserved variables [33,34,35].

Results

Suspension risks

Among 7748 youth with no history of expulsion or suspension, 380 were suspended between 1995 and 1996. The model matched 923 never-suspended youth to the 380 suspended youth and balanced on 67 variables plus the estimated propensity score (Fig. 2).

Risk factors for suspension (associated with greater risk of suspension) included higher delinquency score, more experiences of violence, lifetime marijuana use, daily smoking, household member smoking, friend’s risk behaviors, having a father in prison, parental smoking, and depression score. Protective factors (associated with lower risk of suspension) included never having been truant, attending a private school, interviewer’s positive impressions, parent having graduated college, higher standardized test score, older age, positive expectancies, college intentions, school attachment, systematic decision style, parent’s positive assessment of their child, and higher grades (Fig. 2). After matching, suspended and never-suspended youth had similar values of all 67 factors plus the propensity score (Fig. 2).

Racial disparities in STIs

Respondents who identified as Black were more likely to test positive for trichomoniasis and chlamydia than respondents who did not identify as Black, both in the full sample and after stratifying on suspension status. In the full sample, 5.4% of Black respondents vs. 1.3% of non-Black respondents tested positive for trichomoniasis (p < 0.001); 10.0% vs. 2.7% tested positive for chlamydia (p < 0.001) (Table 1A).

Among Black respondents, 12.1% of suspended young adults tested positive for trichomoniasis compared with 4.8% of non-suspended young adults (p = 0.04), but there was no difference for chlamydia (Table 1B). Among non-Black respondents, suspension did not predict a greater risk of testing positive for either trichomoniasis or chlamydia (Table 1B).

Associations between suspension and STIs

In our sample, 2.00% tested positive for trichomoniasis, which was more common among suspended than non-suspended youth (4.88% vs. 1.85%, p < 0.001). Suspended youth had 2.7 times the odds of trichomoniasis than non-suspended youth (Crude OR = 2.72, 95% CI (1.59, 4.38), p < 0.001) The association was attenuated after controlling for race/ethnicity, gender, and income: suspended youth had 2.5 times the odds of testing positive for trichomoniasis (Table 2). After matching, compared with youth who had never been suspended in 1996, youth who were suspended for the first time between 1995 and 1996 had 2.9 times the odds of trichomoniasis, after adjusting for race, gender, and income (Table 2). Before matching, trichomoniasis was more common among black youth, but that association with race was no longer evident in the matched sample (Table 2). The effect is sensitive to a factor of Γ ≤ 1.65.

Below-median household income explained about 9% of the association between suspension and trichomoniasis (p = 0.02). Among pre-suspension variables: race, gender, STI history, sexual debut, mother’s educational attainment, and mother’s disapproval of birth control did not mediate the association between suspension and trichomoniasis. None of the 34 evaluated post-suspension variables mediated the association between suspension and trichomoniasis at the 0.05 level. However, 6% of trichomoniasis was mediated by expulsion (p = 0.06) and 4% by having a high school diploma (p = 0.14). The pathway between suspension and trichomoniasis was not significantly explained by subsequent criminal justice involvement or lower educational attainment.

In our sample, 3.95% tested positive for chlamydia, which did not differ between suspended and non-suspended youth (5.39% vs. 3.87%, p = 0.18). Suspended youth did not differ from non-suspended youth in the adjusted odds of a positive chlamydia test in multivariate regression, both before and after matching (not shown.)

In 2001, 0.30% tested positive for gonorrhea, which was more common among suspended than non-suspended youth (0.88% vs. 0.27%, p = 0.05). Suspended youth had greater odds of gonorrhea than non-suspended youth (Crude OR = 3.23 (0.95, 11.03), p = 0.06). The sample had only 21 cases of gonorrhea, which did not permit further analysis.

Impulsivity didn’t differ between suspended and matched non-suspended youth in either unadjusted or adjusted models: on average, suspended youth were 0.009 points more impulsive than matched non-suspended youths in multivariate linear regression (p = 0.54).

Discussion

Temporarily removing students from school for the first time predicted greater risk of testing positive for trichomoniasis and gonorrhea 5 years later, and the association between suspension and trichomoniasis was greater among low-income youth. Out-of-school suspension is common and promoted by federal zero-tolerance policy, with over a third of youth suspended over a K–12 school career [5], suggesting a large proportion of youth who are at greater than average STI risk. Suspended youth are at greater risk of arrest [16] and arrested youth have greater STI risk [36], but this analysis suggests that increased STI risk exists even among those who are suspended but not subsequently arrested.

The association between suspension and trichomoniasis could be explained by the theory of labeling and deviance amplification: youth who are suspended may be labeled as deviant and associate with more deviant peers and riskier sexual networks [37]. Past research suggests that police stops and first arrests predict subsequent arrests, and school suspension predicts arrests, which have been explained as effects of labeling and secondary deviance [10, 11, 16].

Out-of-school suspension separates youth from school environments where they have positive influences, including access to lower risk sexual networks. School discipline policies that maintain greater school attachment for all students may reduce students’ propensity to become involved with high-risk sexual networks and decrease their STI risk.

Youth from households with below-median income were more vulnerable to the effects of suspension. Youth from above-median income households have access to social capital resources for overcoming setbacks, including being more likely to come from two-parent households and having college-educated parents who know how to navigate educational systems and mediate with schools [38]. School environments may also be more forgiving of deviation among higher income youth. Youth from below-median income households rely more on school environments for obtaining social capital; when these youth were excluded from school, they were more likely to be left to navigate the situation themselves, which may be because parents with below-median income may have less knowledge or time to assist their children in seeking second chances [38].

Trichomoniasis, caused by the parasite T. vaginalis, is the most common curable STI in the US, with prevalence at the time of this study of 3.1% among all women and 13.3% among non-Hispanic Black women, of whom 85% reported no symptoms [39]. Trichomoniasis appears to increase the risk of HIV infection [40], in women is associated with adverse birth outcomes [41], and in men may be associated with subfertility or infertility [42].

Trichomoniasis is more common in women over 35 than younger women [40]. However, this study finds substantial trichomoniasis prevalence among Black and low-income young adults ages 18–25 who were suspended, suggesting trichomoniasis as a target of STI/HIV prevention interventions in vulnerable populations of young adults. STI/HIV prevention interventions in young adults often measure criminal justice system involvement; this study suggests that interventions that measure suspension and expulsion could measure STI risk in a population at higher risk of criminal justice involvement (13.)

Public health workers reach adolescents through their schools for essential health services, such as health screenings and school-based clinics. STI prevention in schools emphasizes testing, treating, and offering condoms within the schools. This research suggests that schools may also impact the health of adolescents through their disciplinary policies. Previous researchers have called for public health to help to improve school climate, including reducing harsh school discipline policy [2].

Strengths and limitations

This study uses STI tests rather than self-reported STIs, which minimizes both under-report of STIs and self-report bias. STIs are under-reported because many cases of chlamydia and about 80% of trichomoniasis cases are asymptomatic in both men and women [40]. Suspended youth may differ in their likelihood of taking STI tests or reporting STI diagnoses, leading self-reported STIs to have differential misreporting.

It’s unknown why trichomoniasis and gonorrhea were associated with suspension, but chlamydia was not. However, many STI prevention interventions reduce chlamydia but do not reduce gonorrhea or chlamydia. In this case, trichomonas was screened more accurately in this study than in clinical settings. As noted earlier, this study’s trichomoniasis test had sensitivity of 91% in women and 89% in men, which is much greater than the 50% sensitivity of the standard wet-mount test that was the only FDA-approved method until recently, so participants recently screened for trichomoniasis would not have been treated in clinical settings. However, the 80% rate of asymptomatic trichomonas infections suggests many participants would not have seen by clinicians or tested [39].

Outcomes were measured 5 years after suspension and the matched sample comes from a nationally representative sample; previous studies of health sequelae of suspension followed youth only for one year and only in Washington State and Australia [12,13,14]. However, these findings may not generalize to current adolescents. Since this data was gathered, the federal government promoted alternatives to suspension during the years 2011–16, and isolated states and school districts continue attempts to reduce suspension, although suspension continues to be widespread [25]. Public health recognizes that education influences adolescent health [2, 43], but Add Health remains the only national dataset that both measures school suspension and tests youth for STIs.

This study may underestimate the association between suspension and trichomoniasis. Trichomoniasis testing methods have become more sensitive since these results were obtained in 2001 [44]. Low sensitivity biases estimates of association towards the null because the misclassification is not differential by suspension status [45,46,47], suggesting that if this study could be repeated using current, more sensitive trichomoniasis testing, the association between suspension and STI would be stronger.

This study uses matched sampling, which identifies non-suspended youth who are similar to suspended youth on 67 factors, which minimizes potential for confounding on pre-suspension factors. Matching on potential confounders reduces the possibility that extraneous factors explain the observed associations; for example, disadvantaged youth are both more likely to be suspended and acquire STIs [21]. This study also used first suspensions in a subsample of students who reported no previous expulsions or suspensions at baseline; suspended and non-suspended youth were matched on pre-suspension factors, so that the temporal ordering of potential confounders and suspension is clear.

Conclusions

School suspension is associated with greater risk of testing positive for trichomoniasis five years after suspension, suggesting that behavioral and social network changes by suspended youth may persist and result in lasting health effects. Clinicians can use history of school suspension and expulsion as markers of health risks.

Availability of data and materials

The Add Health restricted data is available by application through the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth)

Abbreviations

- FDA:

-

United States Food and Drug administration

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

References

Hamilton DT, Morris M. The racial disparities in STI in the U.S.: Concurrency, STI prevalence, and heterogeneity in partner selection prevalence, and heterogeneity in partner selection. Epidemics. 2015;11:56–61.

Ruglis J, Freudenberg N. Toward a healthy high schools movement: strategies for mobilizing public health for educational reform. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1565–71.

Suh S, Malchow A, Suh J. Why did the black-white dropout gap widen in the 2000s? Educ Res Q. 2014;37(4):19–40.

Martinez S. A system gone berserk: how are zero-tolerance policies really affecting schools? Prev Sch Fail. 2009;53(3):153–8.

Shollenberger TL. “Racial disparities in school suspension and subsequent outcomes: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of youth” in Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion, pages 31–43. Teachers College Press, 2015.

Okonofua JA, Eberhardt JL. Two strikes race and the disciplining of Young students. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(5):617–24.

Becker H. Outsiders: studies of the sociology of deviance. Illinois, Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press of Glencoe; 1963.

Lemert E. Human deviance, social problems and social control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1967.

Paternoster R, Iovanni LA. The labeling perspective and delinquency: an elaboration of the theory and an assessment of the evidence. Justice Q. 1989;6(3):359–94.

Liberman AM, Kirk DS, Kim K. Labeling effects of first juvenile arrests: secondary deviance and secondary sanctioning. Criminol. 2014;52(3):345–70.

Wiley SA, Slocum LA, Esbensen FA. The unintended consequences of being stopped or arrested: an exploration of the labeling mechanisms through which police contact leads to subsequent delinquency. Criminol. 2013;51(4):927–66.

Hemphill SA, Heerde JA, Herrenkohl TI, et al. The impact of school suspension on student tobacco use: a longitudinal study in Victoria, Australia, and Washington state, United States. Health Educ Beh. 2012;39(1):45–56.

Evans-Whipp TJ, Plenty SM, Catalano RF, et al. Longitudinal effects of school drug policies on student marijuana use in Washington state and Victoria, Australia. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):994–1000.

Hemphill SA, Toumbourou JW, Herrenkohl TI, et al. The effect of school suspensions and arrests on subsequent adolescent antisocial behavior in Australia and the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(5):736–44.

Cobb-Clark DA, Kassenboehmer SC, Le T, et al. Is there an educational penalty for being suspended from school? Educ Econ. 2015;23(4):376–95.

Rosenbaum JE. Educational and criminal justice outcomes 12 years after school suspension. Youth Society, January 17 2018.

Painter JE, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, et al. College graduation reduces vulnerability to STIs/HIV among African-American young adult women. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(3):e303–10.

Rosenbaum JE. Graduating into lower risk: chlamydia and trichomonas prevalence among community college students and graduates. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2018;11(1):104–21 Retrieved from: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1713&context=jhdrp.

Satterwhite CL, Joesoef MR, Datta SD, et al. Estimates of Chlamydia trachomatis Infections Among Men: United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(Supplement):S3–7.

Annang L, Walsemann KM, Maitra D, et al. Does education matter? Examining racial differences in the association between education and STI diagnosis among black and white young adult females in the U.S. Pub Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):110–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549101250S415.

Harling G, Subramanian S, Bärnighausen T, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in sexually transmitted infections among young adults in the United States: examining the interaction between income and race/ethnicity. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(7):575–81.

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. FAQ: Questions about field work. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/faqs/aboutfieldwork

Chantala K, Tabor J. Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the add health data. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, August 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/documentation/guides/weight1.pdf

Manhart L, Add Health Biomarker Team. Biomarkers in Wave III of the Add Health study. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2011. Retrieved from: https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/faqs/aboutdata/biomark.pdf

Losen D, Hodson C, Keith MA, et al. Are we closing the school discipline gap? Center for Civil Rights Remedies, UCLA Civil Rights Project, February 2015. Retrieved from https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/federal-reports/are-we-closing-the-school-discipline-gap

Bowen WG, Chingos MM, McPherson MS. Crossing the finish line: completing College at America’s public universities. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; February 2011.

Ou SR, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ, et al. Alterable predictors of educational attainment, income, and crime: findings from an Inner-City cohort. Soc Serv Rev. 2007;81(1):85–128.

Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and Bias in observational studies. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):383–8.

Wolfe SE, Hoffmann JP. On the measurement of low self-control in add health and NLSY79. Psychol Crime Law. 2016;22(7):619–50.

Ho D, Imai K, King G, et al. Matchit: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference, software version 2.4–21. Harvard institute for quantitative Social Sciences, 2008. Retrieved from https://gking.harvard.edu/MatchIt

Montgomery JM, Nyhan B, Michelle TM. How conditioning on post-treatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it. Am J Polit Sci. 2018;62(3):760–75.

Imai K, Keele L, Yamamoto T. Identification, inference, and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):51–71.

Rosenbaum PR. Two R packages for sensitivity analysis in observational studies. Observational Studies. 2015;1:1–17.

Rosenbaum PR. Weighted M-statistics with superior design sensitivity in matched observational studies with multiple controls. J Am Stat Assoc. 2014;109(507):1145–58.

Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity analysis from estimates, tests, and confidence intervals in matched observational studies. Biometrics. 2007;63(2):456–64.

Khan MR, Rosen DL, Epperson MW, et al. Adolescent criminal justice involvement and adulthood sexually transmitted infection in a nationally representative US sample. J Urban Health. 2013;90(4):717–28.

Adams MS, Robertson CT, Gray-Ray P, et al. Labeling and delinquency. Adolescence. 2003;38(149):171.

Lareau A. Unequal childhoods. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003.

Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans EH, et al. The prevalence of trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1319–26.

Poole DN, McClelland RS. Global epidemiology of trichomonas vaginalis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(6):418–22.

Mielczarek E, Blaszkowska J. Trichomonas vaginalis: pathogenicity and potential role in human reproductive failure. Infection. 2016;44(4):447–58.

Menezes CB, Frasson AP, Tasca T. Trichomoniasis: are we giving the deserved attention to the most common non-viral sexually transmitted disease worldwide? Microb Cell. 2016;3(9):404–19.

Cohen AK, Syme SL. Education: a missed opportunity for public health intervention. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):997–1001.

Gaydos CA, Klausner JD, Pai NP, Kelly H, Coltart C, Peeling RW. Rapid and point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis in women and men. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(S4):S31–5.

Copeland KT, Checkoway H, McMichael AJ, Holbrook RH. Bias due to misclassification in the estimation of relative risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105(5):488–95.

Höfler M. The effect of misclassification on the estimation of association: a review. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(2):92–101.

Haine D, Dohoo I, Dufour S. Selection and misclassification biases in longitudinal studies. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:99.

Young JK and Beaujean AA (2011) Measuring personality in wave I of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Front Psychol 2:158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00158.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Constantine Frangakis, Fran Goldscheider, Sandra Hofferth, Clea McNeely, Stephen Raudenbush, James Rosenbaum, and anonymous reviewers for helpful conversations. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spencer Foundation (grant #201000138) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041 (Maryland Population Research Center.) The funders had no role in the research, including design of the data analysis, data analysis, interpretation of the results, writing, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JR conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding, licensed the Add Health data, carried out the analyses, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This paper was ruled exempt by the SUNY Downstate Medical Center Institutional Review Board (FWA# 00003624, Study #440053–1.)

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This paper complies with the contract for the restricted National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health dataset regarding reporting low frequency cells that could lead to individually identifiable information.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Description of control variables

The control variables were 67 potential confounders of the relationship between suspension and STIs, derived from 158 survey items. The 67 control variables are listed in the 9 categories for ease of reading, but these categories do not have statistical implications: demographics, socioeconomic status, sexual risk-taking, relationships with adults, educational factors, parents’ risk behavior, substance use, personality and mental health, and deviance.

Demographics (16 variables from 10 items): Demographics includes gender; nativity; parent’s nativity; age in years; Latino ethnicity, White, Asian, and Black race; male-Black interaction term; respondent’s parent apparent race (Black vs. not); whether the respondents primary home language is English; region of country; and urban/suburban/rural residence.

Socioeconomic status (SES) (6 variables from 6 items): Socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with both suspension and STIs: parent graduated high school; parent graduated 4-year college; parent- reported household income divided by the square root of the household size [31]; parent reported having enough money to pay bills; parent receives public assistance; and parent is currently employed.

Sexual risk-taking (7 variables from 7 items): may be associated with suspension and is associated with STIs: ever having had any of 10 sexually transmitted infections (STI); having ever been pregnant; having ever had sexual intercourse; perceived chances of STIs; number of people they know who have had an STI; friends’ knowledge about condoms; and mother’s attitude towards contraception.

Relationships with adults (6 variables from 34 items): Adolescents’ relationships with their parents and adults in their neighborhood predict likelihood of suspension and sexual risk-taking: lives with both biological parents; parents assessment of relationship with child (how is child’s life going, get along with child, trust child, child doesn’t have a bad temper, 4 items, alpha = 0.67); parental closeness (aggregate of 14 items such as perceived love and warmth, satisfaction with relationship, alpha = 0.81); talk with mother (talk with mother about social, personal, school issues, 4 items, alpha = 0.62); parental monitoring (parents let respondent make own decisions about weekday bedtime, weekend curfew, how much TV, 7 items, alpha = 0.70); and neighborhood support (e.g., know most of the people in the neighborhood, average of 4 binary items, alpha = 0.72).

Personal and school-level educational factors (12 variables from 37 items): Educational factors predict educational attainment and could predict school suspension: standardized test score (Add Health Peabody Vocabulary Test); expectations to attend college; whether the respondent attends a private school; grade point average (average of 4 self-reported grades, alpha = 0.72); positive expectations for the future (aggregate variable of 5 items such as will not be killed by age 21, will live to age 35, alpha = 0.61); school attachment (aggregate variable of 9 items including feeling safe at school, problems with teachers, problems completing homework, alpha = 0.78); school is strict on substance use (top quartile of administrator-reported school discipline policy for alcohol, drugs, and smoking, 8 items, alpha = 0.97); school is strict on civil order (top quartile of administrator-reported school discipline policy for offenses such as stealing school property and verbally abusing a teacher, 7 items, alpha = 0.73); school is strict on non-violent offenses; number of truant days; and having never been truant.

Parent risk-taking (4 variables from 4 items): Youth with parents with greater health risks may have greater likelihood of risk behavior that could lead to both suspension and STIs: parent-reported parent smoking; household member smokes; parent’s health is fair or poor; and one item from 2001: whether the respondents father was ever in prison.

Respondent’s and friends’ substance use (3 variables from 5 items): Substance use could lead to both suspension and is associated with STIs: lifetime marijuana use, regular smoking status, and friends’ substance use (number of friends who drink alcohol monthly, use marijuana monthly, smoke daily, 3 items, alpha = 0.72).

Personality and mental health (9 variables from 28 items): Personality and mental health predicts both deviance and others’ response to an individual’s deviant behavior: self-esteem (aggregate of 11 factors modified from Rosenberg’s scale, alpha = 0.88); conscientiousness (aggregate of 5 items describing systematic approach to solving problems, alpha = 0.78); systematic versus gut-feeling decision-making was measured by the Likert item, “When making decisions, you usually go with your gut feeling without thinking too much about the consequences of each alternative.” where higher means more systematic decision-making style, emotional stability (aggregate of 6 items including have a lot of good qualities, a lot to be proud of, alpha = 0.87) [48]; agreeableness (sum of 3 items: never argue with anyone, never get sad, never criticize other people, alpha = 0.63); personal control was measured by the Likert-scale item “When you get what you want, its usually because you worked hard for it.”; problem avoidance was measured by the Likert-scale items “You usually go out of your way to avoid having to deal with problems in your life.” and “Difficult problems make you very upset.”; and depression was measured by the modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression screen score (19 items, alpha = 0.86).

Deviance (4 variables from 27 items): Deviance predicts both likelihood of suspension and STIs: delinquency was the sum of 15 binary items including running away, hurting someone so badly that they needed medical care, participating in a group fight, lying to parents, and stealing <$50 and > $50 (alpha = 0.80); experiences with violence was the sum of 8 binary variables, such as saw shooting, was shot, shot another (alpha = 0.75.); having a permanent tattoo; and the interviewers assessment of students appearance (attractive, personality attractive, well-groomed, 3 items, alpha = 0.74).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenbaum, J. School suspension predicts trichomoniasis five years later in a matched sample. BMC Public Health 20, 88 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8197-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8197-8