Abstract

Background

As children approach adolescence, they focus increasingly on their appearance and physical attraction due to teenage body-image. Teaching the concepts of adolescent health changes an individual’s attitudes towards parts of the body. The health belief model (HBM) is one of the significant pedagogic models in health education. According to this model, the individual’s decision and motivation for adopting healthy behaviors depends on three separate categories “personal perception, adaptive behaviors, and probability of performing that action or behavior”. This study investigated the effect of teaching puberty health concepts on the basis of a HBM on perceived body image in female adolescents.

Methods

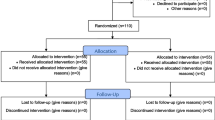

A quasi-experimental research design was used in the study. This study was conducted with 60 sixth grade girls in state elementary schools in Yazd, Iran, that were selected with cluster sampling method and assigned randomly into experimental and control groups. The experimental group were educated in the school during eight 45-min sessions based on the HBM, whereas the control group were educated using the traditional lecturing method. The data were collected with demographic and self-body image questionnaires completed before and after intervention. The data were analyzed with SPSS16 using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Results

The mean age of the participants was 12.16 ± 0.74 years. The findings showed that “perceived body image” and “students’ self-attitude” improved significantly after intervention; yet, no significant difference was found between the subscales “attitudes towards weight” and “satisfaction with various parts of the body”.

Conclusion

The results of the study confirmed the efficacy and efficiency of teaching puberty health on the basis of the HBM on improving perceived body image in female adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Body image is a multi-dimensional structure referring to how people think, feel and behave toward their physical characteristics. Therefore, the three dimensions of body image include evaluation, emotions, and investment (cognition). Evaluation dimension of the body image refers to the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of individuals with their bodies and their assessors’ beliefs about it. The emotional dimension of the body image pertains to the feeling of anxiety, distress and other emotions associated with the body, and the investment dimension of body image refers to the cognitive, behavioral, and affective importance of body for self-evaluation [1,2,3]. An individual’s perception of their body may change regarding the context in which it operates [4]. Body dissatisfaction refers to the negative thoughts and feelings about one’s body and the perceived difference between the current and the ideal body size [5]. The distortion of the body image refers to the incorrect perception of body shape or size [6]. Body image and an attractive appearance is more important among adolescents than other classes of the society [7].

On the other hand, sociocultural factors, especially perceived pressure from others and comparing oneself with others, influences body image [8]. Over the last decades, Iranian girls have been greatly concerned with body slimness and fitness. Satellite propaganda and also commercial ads in health and beauty magazines contain a huge volume of ads on slimness and fitness [9].

Adolescence begins with puberty and is characterized by significant changes in hormonal levels and physical appearance (e.g. rapid physical growth, changes in the face structure and appearance of secondary sexual characteristics), and psychological and social characteristics [10, 11]. Adolescence is associated with a specific vulnerability to mental image disorder [7], and body dissatisfaction is prevalent among adolescents [1]. During these years, girls develop more problems in relation to body image than boys [1, 12], i.e., although maturity draws boys closer to the ideal body of men in terms of culture, it draws girls away from the current ideal fitness and raises concerns about body image [13]. Studies indicated that body satisfaction is low in 46% of girls and 6% of boys; also, 59% of overweight girls and 48% of overweight boys showed low satisfaction with physique [14]. Underweight girls have more body satisfaction than those with normal weight and those overweight, while being underweight and overweight in boys is associated with lower body satisfaction [15, 16]. According to research, body image disorder is associated with eating disorders, psychiatric distress, performance disorders, sexual dysfunction, depression, low self-esteem, preoccupation with appearance and cosmetic surgery [13, 17,18,19,20,21].

Furthermore, changes during puberty contribute to the critical period adolescence brings leading to probable anxiety [22]. Some studies in this field demonstrated that 61.7% of female students experienecd moderate to severe anxiety during their puberty [23]. Additionally, anxiety in the onset of adolescence may predispose teenagers to sensitivity in interpersonal relations and reduced compatibility [22]. Puberty health and awareness of the causes of special changes that occur during this period can reduce the incidences of many problems that can happen during this period and thereby diminish anxiety [23].

School-based educational programs were proposed to help prevent eating disorders and improve the body image of female adolescents. School environments are suitable places to implement health promotion programs, because adolescent students are available and have incentives to participate in educational activities [24]. One of the education models raised in health education is the HBM that reflects the willingness of individuals to perform health-promoting behaviors [25, 26]. According to this model, individuals must first feel threatened by the subject matter (perceived sensitivity). Then, they must perceive the depth of the risk and the severity of its various complications in their physical, social, psychological and economic dimensions (perceived severity). Then, with the positive signs that they receive from their environment (cues to action), they should believe in the usefulness and applicability of the educational programs (perceived benefits). They should also consider the deterrent factors of cues to action less costly than its perceived benefits (perceived barriers) and feel efficient and sufficient in overcoming barriers to behavior change (self-efficacy). So, after these steps, they can ultimately take preventive measures [27].

The effect of education based on this model was investigated in various studies. For example, a study conducted by Shirzadi et al. indicated a significant positive correlation between perceived sensitivity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and increased puberty health in adolescent girls. Also, the perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and cues to action are predictors of physical puberty health behaviors [26]. The findings of the study by Soliman et al. (2018) in Palestine indicated that using the health belief model was effective in improving the knowledge and performance of people at high risk of obesity and making changes in health behavior [28]. The results of Salem et al. (2018) in Egypt also indicated that education based on the HBM not only enhanced the nutritional knowledge of female students, but also improved their eating habits [29]. The findings of another study indicated that the effectiveness of education intervention based on the HBM was effective in students, adopting preventive and controlling behaviors in the principles of puberty health [30].

Regarding the importance of the subject and the stated issues, the present study aimed at answering the question of whether education about puberty health concepts based on the HBM improves perceived body image of female adolescents.

Methods

Design and samples

This was a quasi-experimental pretest-posttest research with a control group that was performed in 2019. The statistical population comprised all sixth grade primary school female students in Yazd, Iran. The research setting was state elementary schools in Yazd, Iran, that were selected with cluster sampling method. Sixty subjects were selected by convenience sampling, and then randomly assigned into two groups of thirty subjects; control and experimental. The age range of participants was 11 to 13 years old and their mean age was 12.16 ± 0.74 years. Given that previous studies proposed the age of 12 as the best age for teaching puberty health [31] and considering that the mean age of the onset of menstrual cycle is reported to be 13 years old in Iran [31, 32], sixth grade primary school girls were selected as participants. The inclusion criteria were: having had at least three menstrual periods and inclination for participation in the study.

Students of both groups completed the Multidimensional Body–Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) as a pre-test and post-test. The experimental group was educated in the school during eight 45-min sessions based on the HBM, whereas in the control group, concepts of puberty health were taught using the conventional lecturing method.

Procedure

On the basis of need, assessment and goals preset by the Iranian Ministry of Education and Training, eight 45-min educational sessions were developed by the researcher (the third author) to be completed during 1 month. According to the HBM, the first three sessions formed the awareness stage providing the required knowledge on puberty and its related hygienic issues. The next three sessions dealt with sensitivity and its perceived severity on the basis of the model. These sessions addressed the specific risks and consequences and prevalent diseases induced by lack of observing puberty health and also the depth of these risks and sensitivity of the complications. The seventh session formed the aspect of perceived benefits that showed advantages bestowed on the individual by adopting preventive behaviors. Finally, the eighth session formed the aspect of perceived barriers that reduce performance of preventive behaviors by the individual (Table 1).

It should be noted that according to the National Iranian Survey, the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia is 39% among adolescent girls. Accordingly, the Iranian Ministry of Health recommends Ferro sulfate 1 tab/week for a 4-month period per year. Since the onset of the educational year is the most suitable time of tablet administration, thus, education in this field was considered as part of puberty health education for adolescents (http://ssu.ac.ir/cms/index.php?id=2299).

Measures

The data collection tool in this study consisted of two parts.

1. Demographic characteristics questionnaire including age, mother’s academic degree, father’s academic degree, mother’s job and father’s job.

2. Multidimensional Body–Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ): This questionnaire is used to evaluate the person’s body image and is a 68-item scale developed by Cash et al. in the early 1980’s [33, 34]. The total score of this inventory, which uses a 5-point Likert scale, ranges between 68 and 339. This tool includes 3 subscales: “self-attitude”, “attitude towards weight” and “satisfaction with various parts of the body”.

In the self-attitude subscale, there are three prominent physical aspects, namely, physical appearance, physical fitness, and health, each of which includes two areas of evaluation and understanding (evaluation and perceiving appearance, evaluation and perception of physical fitness, evaluation and perception of health). Individuals showed the level of their agreement with each item in terms of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 indicating definitely disagree to 5 indicating definitely agree. The scores in the subscale ranged between 54 and 270. A higher score was indicative of higher satisfaction.

In the subscale of “satisfaction with various parts of the body” such as face, upper trunk, trunk and lower trunk, muscular consistency, weight, height, and general appearance, 1 indicated completely dissatisfied and 5 indicated completely satisfied. The scores in the subscale ranged between 8 and 40.

The subscale of “attitude towards weight” includes “mental obsession and individual’s self-assessment of weight”. Mental obsession shows anxiety with obesity and attention to body weight, nutritional diet, and eating controlled behavior. The scores in the subscale ranged between 6 and 29.

The validity of the main sections of the questionnaire was reviewed and verified by Brown, Cash and Mikulka (1990), and showed a reliability coefficient of 81% [35]. The Multidimensional Body–Self Relations Questionnaire is a standard questionnaire used in various studies [36,37,38,39]. According to previous studies, this questionnaire is acceptable in Iranian samples according to psychological fitness [40,41,42,43,44]. Rahati (2007) investigated the validity of the multi-dimensional self-image questionnaire on Iranian adolescents. The results suggested acceptable validity of the tool. Also, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.85 for female participants [41], indicating that the instrument had an acceptable confidence level.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS16. Statistical analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage, mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (univariate covariance).

Results

In the present study, a total of 60 people participated in the study, and there was no subject attrition. The mean age of the participants was 12.16 ± 0.74. The youngest of participants was 11. For the majority of the participants, 71.7% of fathers and 76.7% of mothers held a diploma or a higher degree, 78.3% of mothers were homemakers and 46.7% of fathers were self-employed. The two groups were identical in terms of demographic characteristics.

Table 2 indicates the mean and standard deviation of body image scores and their components in the experimental and control groups separately in the pre-test and post-test phases (Table 2).

Significant differences were found between groups in pretest scores. Therefore, pretest scores became covariates in subsequent analysis and the research questions were answered using ANCOVA. To use covariance, some assumptions were considered. Therefore normality of data distribution was assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P > 0.05). Then, Levene’s test was used to establish equality of variances and the result confirmed this. Also, the homogeneity of regression slope was established.

In order to study the effect of educational intervention using HBM, the ANCOVA was used. The results are displayed in Table 3.

As a result of the ANCOVA in Table 3, a significant difference was found between the groups on “body image” (F = 4.617, P = 0.036) and “self-attitude” (F = 8.528, P = 0.005). Therefore, the education of the concepts of puberty health based on the HBM was effective in improving “body image” and “self-attitude”.

Considering the results of the table above, no significant difference was found between groups on the subscales of “satisfaction with various parts of the body” (F = 2.003, P = 0.162) and “attitude towards weight” (F = 0.939, P = 0.337) (Table 3). Therefore, it can be concluded that the intervention was not effective on improving “satisfaction with various parts of the body” and “the students’ attitude towards their weight”.

Discussion

The present study aimed at investigating the effectiveness of educating the concepts of puberty health based on HBM for improving body image in female students. Based on the results of this study, the scores of the satisfaction dimension increased after the educational intervention in both groups, but there was no significant difference between the two groups after intervention. The study by Hinz indicated that provision of an educational program to help boys and girls to better accommodate themselves to inevitable changes in puberty reduces the risk of dissatisfaction among the students [45]. Futhermore, the findings of the present study were not consistent with the results of Abedi-Parija et al. (2017), where part of their intervention replaced negative beliefs with real and logical thoughts and cognitive restructuring and improving satisfaction with the body [46]. In a study by Cousineau et al. (2010), the body dissatisfaction prevention program and puberty health education were effective in reducing body dissatisfaction [47]. The reason for such inconsistency may be due to differences in the implementation of educational programs, the population and research tools.

One of the most important causes of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls is an unrealistic ideal symbol of feministic beauty in recent years, which largely emphasizes weight loss and an idealized body. Since achieving the ideal body determined for most girls is inaccessible, it can lead to body dissatisfaction and consequently, to a variety of diseases, and physical, mental and social harms. This should be taken into consideration by policymakers, managers, teachers, and families to improve dissatisfaction through providing appropriate programs including appropriate educational programs.

After education, the attitude score of individuals increased concerning their weight in both groups, but there was no significant difference based on ANCOVA. In the study of McArthur et al. (2018), the HBM had low predictive power in predicting the body mass index [25]. Crockett also states that since puberty is a physiological process, adolescents ought to be taught to better perceive puberty changes and acquire a positive attitude towards body image. Behavioral change approaches should be used to promote selection of accurate choices with regard to various issues, especially body weight [48]. It is important to note that the overall appearance of individuals at this age is of particular importance to them, and proper education about increasing and decreasing body mass during this period can reduce this concern with emphasis on body swelling at certain times, e.g., menstruation.

The results of the current study indicated that the girls who received education on the concepts of puberty health based on the model had lower levels of concern about health, appearance and fitness than the girls who received routine education. These findings were consistent with the results of other studies [25]. The results of Salem et al. (2017) indicated that there was a significant difference in pre-test and post-test education based on HBM in improving health and body appearance [29]. O’Neill et al. (2016) investigated a curriculum based on principles of HBM and social learning theory in improving the fitness and safety of elementary school students. The results indicated that this curriculum was effective in promoting fitness and safety of students [49]. In explaining this finding, it can be pointed out that providing girls with puberty education based on the model, provides them with a clearer understanding of their bodies, enhances their self-esteem and self-confidence, and adds to their passion for life and motivation for success.

Based on the results of this study, there was a significant difference between the body image of the control and the experimental groups after intervention based on the HBM. The findings of this study were consistent with the results of other studies [46, 47, 50]. By focusing on perceptions, thoughts, and increasing beliefs about the usefulness and applicability of the program and understanding the obstacles, being educated on the puberty health concepts based on the HBM helps students to have a more realistic image of their bodies.

The self-reporting tool was a limitation of the present study, and similar to other self-reporting tools, there was the possibility of fatigue, and lack of sufficient opportunity. Thus, some contributors may have refused to provide real answers. The lack of control of intervening variables such as the different socio-cultural level of families was another limitation of this study. Hence, it is recommended that a similar study with controlled intervening variables be designed.

Conclusion

Based on the results, teaching health concepts on the basis of HBM would improve perceived body image and self-attitude among female adolescents. Consequently, offering educational programs during puberty, especially for adolescent girls while raising their awareness, lays the groundwork for posing questions and solving the problems of puberty that can affect body image. Model-based education will have a greater effect on body image improvement by focusing on perceptions and enhancing beliefs about the applicability of the program and understanding the benefits and barriers.

Availability of data and materials

Sharing the data is not possible due to an agreement with the participants on the confidentiality of the data.

Abbreviations

- HBM:

-

Health Belief Model

- MBSRQ:

-

Multidimensional Body–Self Relations Questionnaire,

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

References

Kantanista A, Król-Zielińska M, Borowiec J, Osiński W. Is underweight associated with more positive body image? Results of a cross-sectional study in adolescent girls and boys. Span J Psychol. 2017;20(e8):1–6.

Cash TF. Cognitive-behavioral perspectives on body image. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: a handbook of science, practice, and prevention. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

Smolak L. Body image in children and adolescents: where do we go from here? Body Image. 2004;1:15–28.

Krane V, Waldron J, Michalenok J, Stiles-Shipley J. Body image concerns in female exercisers and athletes: a feminist cultural studies perspective. Women Sport Phys Act J. 2001;10:17–54.

Grogan S. Body image: understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. 3rd ed. USA: Routledge; 2017.

Reina AM, Monsma EV, Dumas MD, Gay JL. Body image and weight management among Hispanic American adolescents: differences by sport type. J Adolesc. 2019;74:229–39.

Sattler FA, Eickmeyer S, Eisenkolb J. Body image disturbance in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00725-5.

Garrusi B, Garousi S, Baneshi MR. Body image and body change: predictive factors in an Iranian population. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:940–8.

Haghighatian M, Ansari E, Asgari N. Physical fitness and social factors case of women in Isfahan. Womens Stud. 2013;10:159–80 (in Persian).

Blakemore S, Burnett S, Dahl RE. The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:926–33.

Choi M-S, Kim E-Y. Body image and depression in girls with idiopathic precocious puberty treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2016;21:155.

Ramos MI, Vaz FJ, Rodríguez L, Cebria JM, Fernandez N, Gonzalez EM, et al. EPA-0407–differences in perception of body image between boys and girls during puberty. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:1.

Stice E, Hayward C, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Taylor CB. Body-image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:438–44.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Irving LM. Weight-related concerns and behaviors among overweight and nonoverweight adolescents: implications for preventing weight-related disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:171–8.

Kostanski M, Fisher A, Gullone E. Current conceptualisation of body image dissatisfaction: have we got it wrong? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1317–25.

Zach S, Zeev A, Dunsky A, Goldbourt U, Shimony T, Goldsmith R, et al. Perceived body size versus healthy body size and physical activity among adolescents–results of a national survey. Eur J Sport Sci. 2013;13:723–31.

Ramirez AL, Perez M, Taylor A. Preliminary examination of a couple-based eating disorder prevention program. Body Image. 2012;9:324–33.

Blais RK, Monson CM, Livingston WS, Maguen S. The association of disordered eating and sexual health with relationship satisfaction in female service members/veterans. J Fam Psychol. 2019;33:176–82.

Rodgers RF, Nichols TE, Damiano SR, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ. Low body esteem and dietary restraint among 7-year old children: the role of perfectionism, low self-esteem, and belief in the rewards of thinness and muscularity. Eat Behav. 2019;32:65–8.

Yazdani N, Hosseini SV, Amini M, Sobhani Z, Sharif F, Khazraei H. Relationship between body image and psychological well-being in patients with morbid obesity. Int J Commun Based Nurs Midwifery 2018;6:175–184. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29607346.

Golparvar M, Kamkar M, Riamanchian S. The relationship of overweight with self-confidence, depression, lifestyle and body image in women representing their weight loss centers. J Knowl Res Psychol. 2007;32:121–44 (in Persian).

Holder MK, Blaustein JD. Puberty and adolescence as a time of vulnerability to stressors that alter neurobehavioral processes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:89–110.

Mokari H, Khaleghparast S, Samani LN. Impact of puberty health education on anxiety of adolescents. Heal Sci. 2016;5:284–91.

O’Dea JA, Abraham S. Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: a new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:43–57.

McArthur LH, Riggs A, Uribe F, Spaulding TJ. Health belief model offers opportunities for designing weight management interventions for college students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50:485–93.

Shirzadi S, Jafarabadi MA, Nadrian H, Mahmoodi H. Determinants of puberty health among female adolescents residing in boarding welfare centers in Tehran: an application of health belief model. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:432.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th edition. San Francisco, CA: Wiley; 2008.

Soliman NM, Elsayied HAE, Shouli MM. Application of health belief model among youth at high risk for obesity in West Bank (Palestine). Am J Nurs Sci. 2018;7:86–96.

Salem GM, Said RM. Effect of health belief model based nutrition education on dietary habits of secondary school adolescent girls in Sharkia governorate. Egypt J Commun Med. 2018;36:35–47.

Valizade R, Taymoori P, Yousefi FY, Rahimi L, Ghaderi N. The effect of puberty health education based on health belief model on health behaviors and preventive among teen boys in Marivan, north west of Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2016;4:3271–81.

Djalalinia S, Tehrani FR, Afzali HM, Hejazi F, Peykari N. Parents or school health trainers, which of them is appropriate for menstrual health education? Int J Prev Med 2012;3:622–627. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23024851.

Kashani HH, Kavosh MS, Keshteli AH, Montazer M, Rostampour N, Kelishadi R, et al. Age of puberty in a representative sample of Iranian girls. World J Pediatr. 2009;5:132–5.

Cash TF. The great American shape-up: body-image survey report. Psychol Today. 1986;20:30–7.

Cash TF. Multidimensional Body–Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ). In: Wade T. (eds) Encycl Feed Eat Disord. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-087-2_3-1.

Brown TA, Cash TF, Mikulka PJ. Attitudinal body-image assessment: factor analysis of the body-self relations questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:135–44.

Marco JH, Perpiñá C, Roncero M, Botella C. Confirmatory factor analysis and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire-appearance scales in early adolescents. Body Image. 2017;21:15–8.

Cruzat-Mandich C, Díaz-Castrillón F, Pérez-Villalobos CE, Lizana P, Moore C, Simpson S, et al. Factor structure and reliability of the multidimensional body–self relations questionnaire in Chilean youth. Eat Weight Disord Anorexia, Bulim Obes. 2019;24:339–50.

Vossbeck-Elsebusch AN, Waldorf M, Legenbauer T, Bauer A, Cordes M, Vocks S. German version of the multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire–appearance scales (MBSRQ-AS): confirmatory factor analysis and validation. Body Image. 2014;11:191–200.

Argyrides M, Kkeli N. Multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire-appearance scales: psychometric properties of the Greek version. Psychol Rep. 2013;113:885–97.

Khodabandeloo Y, Fat’h-Abadi J, Motamed-Yeganeh N, Yadollahi S. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire (MBSRQ) in female Iranian University students. Pract Clin Psychol. 2019;7:187–96.

Rahati A. The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral strategies on body image modification and self esteem of female adolescent [dissertation]. Iran: Tehran University; 2007.

Sabeti F, Gorjian Z. The relationship between the satisfaction of body image and self-esteem among obese adolescents in Abadan, Iran. Iran J Diabetes Obes. 2013;5:126–31.

Shahyad S, Pakdaman S, Shokri O, Saadat SH. The role of individual and social variables in predicting body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms among Iranian adolescent girls: an expanding of the tripartite influence mode. Eur J Transl Myol. 2018;28:99–104.

Raghibi M, Minakhany G. Body management and its relation with body image and self concept. Knowl Res Appl Psychol. 2012;12:72–81.

Hinz A. Improving body satisfaction in preadolescent girls and boys: short-term effects of a school-based program. Electron J Res Educ Psychol. 2017;15:241–58.

Abedi-Parija H, Sadeghi S, Shalani B, Sadeghi E. The effectiveness of group cognitive-behavioral intervention on improvement of negative body image in male adolescents. Daneshvar Med. 2017;24:1–21 (in Persian).

Cousineau TM, Franko DL, Trant M, Rancourt D, Ainscough J, Chaudhuri A, et al. Teaching adolescents about changing bodies: randomized controlled trial of an internet puberty education and body dissatisfaction prevention program. Body Image. 2010;7:296–300.

Crockett LJ, Deardorff J, Johnson M, Irwin C, Petersen AC. Puberty education in a global context: knowledge gaps, opportunities, and implications for policy. J Res Adolesc. 2019;29:177–95.

O’neill JM, Clark JK, Jones JA. Promoting fitness and safety in elementary students: a randomized control study of the Michigan model for health. J Sch Health. 2016;86:516–25.

O’Dea JA. School-based health education strategies for the improvement of body image and prevention of eating problems: an overview of safe and successful interventions. Health Educ. 2005;105:11–33.

Acknowledgements

The present article was derived from a Master’s degree thesis in Educational Technology. Thereby, the authors extend their gratitude and appreciation to the students and school administrators and teachers who patiently helped us to complete this study.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (MB-SH, SV and MB-SH) have participated in the conception and design of the study. MB-SH contributed the data collection and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. MB-SH and SV critically revised and checked closely the proposal, the analysis and interpretation of the data and design the article. MB-SH and MB-SH carried out the analysis, interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript. MB-SH and VS has been involved in revising the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The questionnaires were submitted to the research units after obtaining legal permission and observing ethical issues. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Yazd Branch, Iran, with the ethics code no. IR.IAU.YAZD.REC.1398.012. In order to comply with the research ethics, an informed consent form was completed by all participants and their parents. Since the participants were under 16 years old, an informed consent form was completed by all parents. Participants were assured about the confidentiality of the information they provided and all participants expressed their consent to enter the study. All participants were aware of the research objectives and the voluntary nature of their participation. They were told they could attend each stage of the study.

Consent for publication

The article does not contain any individual’s details and consent for publication is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M., Vaziri-Yazdi, S. & Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M. The effect of teaching puberty health concepts on the basis of a health belief model for improving perceived body image of female adolescents: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health 20, 370 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08482-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08482-2