Abstract

Background

Skin disease is a global public health problem that often has physiological, psychological and social impacts. However, it is not very clear how to adapt to these impacts, especially psychosocial adaptation of patients with skin disease.

Methods

We searched EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO from 2009 to 2018. The following themes were extracted from the included articles: the concepts, related factors, and interventions for psychosocial adaptation of patients with skin disease. Two reviewers independently screened and analyzed.

Results

From 2261 initial records, 69 studies were identified and analyzed. The concept of psychosocial adaptation in patients with skin disease was referred to under an assortment of descriptions. The related factors for psychosocial adaptation in patients with skin disease included the following: demographic factors (sex, age, education level, ethnicity, BMI, sleep quality, marital status, exercise amount, family history, the use of topical treatment only, personality and history of smoking); disease-related factors (disease severity, clinical symptoms, localization and duration); psychological factors (anxiety/depression, self-esteem, body image, stigma and suicidal ideation); and social factors (social support, social interaction, sexual life, economic burden and social acceptance). Despite being limited in quantity, several studies have clarified the benefits of adjuvant care in the form of cognitive behavioral training, educational training and self-help programs, all of which have become common methods for dealing with the psychosocial impacts.

Conclusions

Based on the previous literatures, we constructed a protocol of care model for psychosocial adaptation in patients with skin disease. It not only provided the direction for developing new instruments that could assess psychosocial adaptation statue, but also a basis for helping patients adjust to changes in skin disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the largest organ of the human body, the skin is the main barrier that resists the outside world.1 Because skin diseases are often not life-threatening, attention and funds may be invested in diseases considered more serious. However, the psychosocial and occupational impact of skin disease is frequently comparable to, if not greater than, other chronic medical conditions.2 The lifetime prevalence of skin disease was reported from European five countries, with skin disease including eczema (14.2%), atopic dermatitis (7.9%), psoriasis (5.2%) and vitiligo (1.9%).3 With the deterioration of environment and various pressures, the incidence of skin disease has increased in recent years. It has become a global public health problem.4 Many skin diseases have a chronic and repeated process, which requires us to treat the disease and help patients positive adaptation.5

Roy defines adaptation as the process and outcome whereby thinking and feeling persons as individuals or in groups use conscious awareness and choice to create human and environmental integration, including physiological, psychological and social aspects.6The British Association of Dermatologists suggested that 85% of patients with skin disease have reported that the psychosocial impacts of their disease are a major component of illness, which is a concerning statistic.7 Psychological and social analyses reveal that if the body is stimulated by stress and the external environment, the emotional state will change as an instinctive response.8 Skin disorders can significantly affect the psyche, and the psyche can significantly affect skin disorders through psycho-neuro-immuno-endocrine and behavioral mechanisms.9 And the stress is related to functional and psychological processes in skin disease patients with high levels of anxiety sensitivity.8 In response to the environmental pressures of extreme grief and fear, individuals will experience continuous tension.10 Skin diseases distort body image, which may have a negative impact on the psychosocial health and quality of life (QOL) of patients.11 A high severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is related to high disease severity and low QOL and work productivity.12 The psychosocial adjustment to vitiligo is mainly affected by subjective factors.13

Therefore, it will be limited to attempts to understand the psychosocial impacts of psoriasis from the perspective of current measurements of demographic characteristics and disease severity.14 It is imperative to develop appropriate psychosocial adaptation (PA) evaluation tools for patients with skin disease.15 Various clinic models have been described to provide specialised psychodermatology care in specific settings.16 However, it is not clear the concepts, related factors and interventions of PA for patients with skin diseases. They were described by this scoping review. Based on the previous literatures, we attempted to present a protocol of care model for PA in patients with skin disease.

Methods

A scoping review can examine and clarify broader areas than a systematic review to identify gaps in the evidence, clarify key concepts, and report on the types of evidence that address and inform practices in the topic area.17 Therefore, a scoping review method was chosen to allow for the inclusion of different study designs; this type of study follows the methodology model proposed by Arksey and O’Malley to map the various concepts underpinning this research area, as well as to clarify the related factors and interventions.18 We followed the guidelines of the PRISMA-ScR19 which is included as an Additional file 1 document to this paper. We did not provide detailed critical appraisal of individual studies or meta-analyses as this is a developing area of research. The steps of the review are outlined below.

Identifying the research questions

This scoping review aimed to identify the various concepts and related factors of PA for patients with skin disease by mapping the existing literature in the field to provide a basis for developing instruments to assess the status of PA. Additionally, mapping showed a variety of interventions.

Identifying relevant studies

The search strategy was formed by the project team and consulting with information specialists (see Additional file 2). The following databases EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO were chosen and searched from 2009 to 2018 for publications with no limit on language, which covered a wide range of subjects including medicine, psychosociology and nursing. EndNote was applied to exclude duplicate records and manage inclusion literatures.

Selecting the literature

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Population: Patients experiencing skin diseases diagnosed as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, eczema, vitiligo or chronic urticaria.

-

Range of concepts: The psychosocial adaptation of patients in different skin conditions. According to previous research and team discussion, the following concepts were often used to reflect psychosocial impacts of patients with skin diseases: anxiety/depression, body image, stigma, self-esteem, social support, family function, financial costs and work. Some studies even equated the PA of patients with the QOL.

-

Context: Adult population for 18 years old or older.

All articles provided primary data on the various concepts, related factors and interventions of PA for patients with skin disease from 2009 to 2018. Single case reports and comments were excluded. Firstly, in order to avoid missing valuable literature, two researchers conducted three rounds of assessments that included reading the study titles and abstracts for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Second, the full texts of the studies identified through screening were independently assessed for eligibility by two authors. Third, the studies were classified for mapping according to the definitions and descriptions of methods provided in the publication.17 Finally, data extraction was undertaken by one author (JBI systematic review researcher) using a structured form. The accuracy of data extracted from the included studies was checked by another author. Any disagreements were resolved by a larger team discussion.

Charting the data

A total of 69 articles were finally included in this review and were then subjected to data charting. The data charting took the following information into consideration: author(s), year of publication, country of origin, study population, sample size, methodology, concept, assessment tool, related factors and interventions of PA for patients with skin diseases.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the literature

The various concepts of PA for patients with skin diseases were identified. The related factors in the papers reviewed were classified as demographic, physiological, psychological or social factors. The interventions were reported.

Results

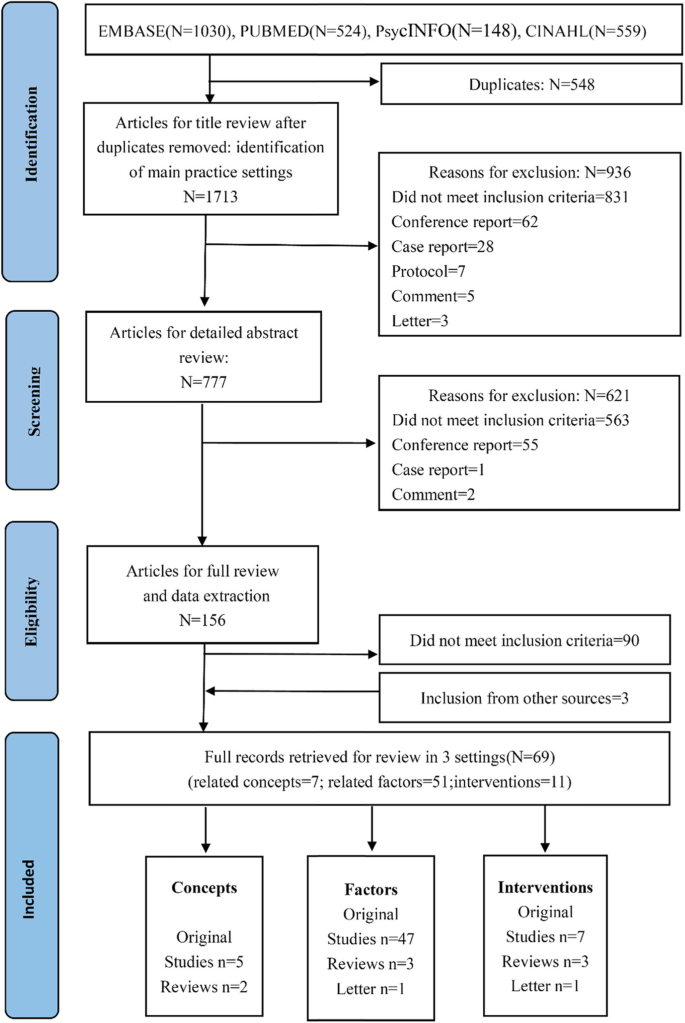

The search strategy yielded 2261 potential papers. After removing duplications (n = 548) and eliminating 936 by a first pass through the titles and abstracts, the potentially relevant literature was screened in two rounds and resulted in 69 studies. The remaining studies were clustered in the following three facets: i) various concepts of PA (n = 7), ii) related factors of PA (n = 51), and iii) interventions (n = 11) (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the included literature are presented in Table 1.

Various concepts of psychosocial adaptation for patients with skin disease

A clear conceptual definition of psychosocial adaptation is identified by Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis, and the identified attributes of PA include change, process, continuity, interaction and influence, all of which were present in the multidisciplinary literature reviewed, thus demonstrating the wide use of the concept.20, 21 In the nineteenth century, skin diseases were linked to psychosocial factors. The mechanism was proposed and clarified in subsequent decades, and multidisciplinary collaboration was crucial to promote the adaptation of patients with skin diseases.22 PA was referred to under an assortment of descriptions in skin diseases including psychosocial factor,11, 23 burden,24, 25 impact,26 morbidity,15 and aspect.27 The measurement methods used in the literature are shown in Table 2.

Related factors of psychosocial adaptation for patients with skin disease

Table 3 shows the related factors of PA for patients with skin disease including the demographic, disease-related, psychological and social factors.

Demographic factors

With regard to demographic facets, the key factors reported were sex,13, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 age,31, 35, 38,39,40,41 education level,34, 36, 41,42,43 ethnicity,32, 42 BMI,44, 45 sleep quality,46, 47 marital status,28, 48 exercise amount,49 family history,43 the use of topical treatment only,32 personality13 and history of smoking.44 Females were more prone to depressive and psychosocial maladaptation than males with skin disease.28, 31, 50 Because females were more likely to believe in the importance of physical appearance to their personal or social values than males, their investment in physical attractiveness was significantly increased. Psychological impacts related to skin disease may largely be attributed to the patients’ maladaptive assumptions about appearance and society’s focus on the perfect body and beauty. However, the genital lesions in males were more prone to cause sexual dysfunction than the lesions in females.35 There was no agreement for the impact of age on psychosocial level.31 Younger psoriasis patients can experience feelings of embarrassment, disturbance of daily activities, poor physical health, and low productivity at work. Nevertheless, it was also found that old age was related to a high risk for depression in atopic dermatitis patients. Education level also influenced the QOL of patients with psoriasis.

Disease-related factors

The disease-related factors were severity,12, 31,32,33,34, 36, 39,40,41, 43, 49, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 clinical symptoms (itching,47, 48, 52, 61 pain, scaling),12, 54, 62 localization (visible and genital parts)28, 34, 43, 50, 63, 64 and duration.28, 29, 33, 43 The severity of the skin disease was associated with the level of depression and anxiety, and it had a negative effect on QOL.23, 27 Itching is the cardinal clinical symptom of patients with skin disease, which can result in sleep deprivation and mental disorders. However, the localization of the skin lesions was often more important than the disease severity and was associated with negative mental health, including depression, social anxiety, self-image disorder, and stigmatization. The ‘sensitive’ body regions were defined as the visible parts of the body, which included the scalp, face, neck, hand and fingernails.43 Additionally, the psoriasis lesions located on the genitals, buttocks, abdomen, chest or lumbar region were more likely to lead to sexual dysfunction.64 The clinical symptoms of psoriasis, particularly itching, pain and scaling, negatively affected health outcomes and work productivity.62

Psychological factors

With respect to psychological facet, the related factors included anxiety and depression,36, 39, 40, 42, 44,45,46, 48, 55, 60, 61, 65 self-esteem,13, 34, 53, 66 body image,30, 53, 67 stigma29, 41 and suicidal ideation.46, 48 Skin disease patients have a high level of anxiety or depression. Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 were found in both psoriasis and depression, indicating that the inflammatory process may be involved in the progression of both diseases.68 Depression in psoriasis patients was related to a high risk of stroke and cardiovascular death, especially during acute depression.69 The adaptation of vitiligo patients has been considered to be affected by self-esteem levels. The following five common themes of stigma have been identified in patients with psoriasis: anticipation of rejection, feelings of being flawed, sensitivity to the attitudes of society, secretiveness, guilt and shame.15 A high level of stigma and low self-esteem have negative effects on patient compliance.

Social factors

The social factors of PA in patients with skin disease were: social support,29, 37, 40, 49, 57, 70 social interaction,36, 67, 70, 71 sexual life49, 63 and economic burden 42, 72,73,74,75,76 (medical expenses,52 work productivity,12, 52, 54, 59, 62, 77, 78 income level43, 51). It was found that high levels of perceived social support were positively correlated with the low occurrence of depressive symptoms.11 The marriages and relationships of 50% of vitiligo patients were negatively affected by skin disease.79 Due to its physical symptoms and the stigma caused by the appearance of skin, psoriasis can be considered a socially isolating disease.68 Psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin disease, seems to be related to erectile dysfunction, which was a predictor of future cardiovascular disease.65 It is critical to accurately evaluate effective treatments of skin disease to understand the interaction between lost productivity, direct costs and quality of life.76

Interventions of psychosocial adaptation for patients with skin disease

The outcomes of PA include positive and negative aspects.20 Table 4 shows the PA interventions of skin disease included cognitive behavioral therapy,80,81,82,83,84,85,86 educational training,82, 87,88,89 self-help programs,80, 81, 84 psychotherapy84 and communication.90

Discussion

This scoping review analyzed the contents of 69 papers with results that were three-fold: i) some reported the various concepts of PA for patients with skin disease, which required that future research should unify the terms; ii) some reported the related factors of PA for patients with skin disease, which provided a basis for developing instruments that assess the status of PA for patients with skin disease; and iii) others reported a variety of interventions, which provided a basis for formulating a protocol of care model for PA in patients with skin disease.

Patients with skin disease often have to cope with a condition that leads to physical disfigurement, psychological destruction and social stigma. Although a large number of studies have been conducted on the treatment of patients with skin diseases, few studies have been directed towards the status and interventions of the psychosocial adaptation for patients with skin disease. It was shown that psychoeducational intervention for acceptance and managing social impact is needed, which is also the first step to informing the development of a patient-centered psychological intervention.91 Adding nondrug treatments such as biofeedback, cognitive behavioral methods, CES, EFT, EMDR, hypnosis, mindfulness meditation, placebo effect, or suggestions often enhances the therapeutic effect.9 The major routes for coping with the impacts of skin disease include the doctor-patient relationship, education of the patient and the community about the actual nature of these diseases, and more structured therapeutic strategies such as individual, group, or behavioral therapy. In response to patient feedback and NICE guidelines, the ‘Psoriasis Direct’ service was launched in 2013; this service aims to give patients open access to specialist nurses when they need it for secondary care, and ‘Psoriasis Direct’ has received overwhelmingly positive feedback.92 Despite being limited in quantity, several studies have clarified the benefits of adjuvant care in the form of cognitive behavioral training, educational training and self-help programs. An electronic health record system for patients with skin disease has not been established for long-term follow-up, so there is a lack of a systematic care model and financial support.93

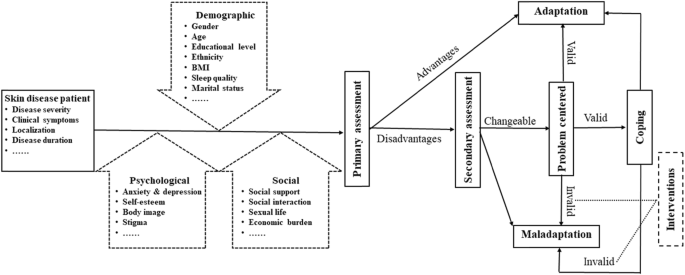

Most researchers have posited models in which adaptation is conceptualized as a process of change in reaction triggered by functional limitations associated with external environmental antecedents (eg, injury, accidents, traumas) or internal pathogenic condition (eg, disease).21 And the adaptation process suggests an unfolding paradigm in which the individual’s reactions to his or her chronic illness or disability follow a stable sequence of phase (ie, partially overlapping and nonexclusive psychosocial reactions), or stage (ie, discrete and categorically exclusive psychosocial reactions) that can be temporally and hierarchically ordered. Others view psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability as one of a set of independent and nonsequential patterns of human behavior.21 Based on previous theories and studies, when individuals have skin diseases, the individuals will make different primary assessments due to their different demographic, psychological and social conditions. If individuals think they can cope with the skin disease, they will adopt a positive attitude and behavior to face it, which refers to positive psychosocial adaptation. However, if individuals think they cannot cope with the skin disease, they will suffer from psychosocial maladaptation or conduct a secondary assessment. The above two situations continued to occur after the secondary assessment. If we can carry out targeted psychosocial intervention before the individual experience invalid adaptation, we can help patients positively deal with the skin disease and then promote patient adaptation (Fig. 2).

Strength and limitations

This research included studies in different settings, which brought to light the range of concept and related factors of PA for patients with skin disease, which could provide the direction for further research. A scoping review method was chosen to allow for the inclusion of different study designs, and it does not involve detailed critical appraisal of individual studies or meta-analyses. Considering partial databases selected and gray literature not included, the results are used only as an overview of the field.

Conclusion

The clinical process of a series of skin diseases is the result of a complex and sometimes reciprocal interaction among biological, psychological, and social factors, all of which can play a role in the occurrence and development of skin diseases. This review described the range of concept and related factors of psychosocial adaptation for patients with skin disease, which could contribute to the development of new instruments. The protocol of care model based on previous theory and research could provide directions for care and policy that promote psychosocial adaptation for patients with skin disease. Further research is needed to examine the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions based on the protocol of care model for individuals with skin disease.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Psychosocial Adaptation

- QOL:

-

Quality of Life

References

Basavaraj KH, Navya MA, Rashmi R. Dermatology. USA: Elsevier; 2010.

Hong J, Koo B, Koo J. The psychosocial and occupational impact of chronic skin disease. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):54–9.

Svensson A, Ofenloch RF, Bruze M, Naldi L, Cazzaniga S, Elsner P, Goncalo M, Schuttelaar MA, Diepgen TL. Prevalence of skin disease in a population-based sample of adults from five European countries. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1111–8.

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59.

Jafferany M, Pastolero P. Psychiatric and Psychological Impact of Chronic Skin Disease. Prim Care CNS Disord. 2018;20(2). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.17nr02247.

Roy C. Extending the Roy adaptation model to meet changing global needs. Nurs Sci Q. 2011;24:345–51.

Working Party Report on Minimum Standards for Pyscho-Dermatology Services 2012. http://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?itemtype=document&id=1622. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Dixon LJ, Witcraft SM, McCowan NK, Brodell RT. Stress and skin disease quality of life: the moderating role of anxiety sensitivity social concerns. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:951–7.

Shenefelt PD. Behavioral and psychotherapeutic interventions in dermatology. The handbook of behavioral medicine, vol. Vols. 1–2: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. p. 570–92.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:466–75.

Wojtyna E, Lakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. Gender, body image and social support: biopsychosocial deter-minants of depression among patients with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:91–7.

Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, Roberts J, Sullivan E. Increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is associated with increased disease severity, reduced quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Dermatol Online J. 2015;10:21 pii: 13030/qt1x16v3dg.

Bonotis K, Pantelis K, Karaoulanis S, Katsimaglis C, Papaliaga M, Zafiriou E, et al. Investigation of factors associated with health-related quality of life and psychological distress in vitiligo. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:45–9.

Perrott SB, Murray AH, Lowe J, Mathieson CM. The psychosocial impact of psoriasis: physical severity, quality of life, and stigmatization. Physiol Behav. 2000;70:567–71.

Foggin E, Cuddy L, Young H. Psychosocial morbidity in skin disease. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78:C82–6.

Zhou S, Mukovozov I, Chan AW. What is known about the Psychodermatology clinic model of care? A systematic scoping review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(1):44–50.

Aromataris E, Munn Z. Joanna Briggs institute Reviewer’s manual. South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Londono Y, McMillan DE. Psychosocial adaptation: an evolutionary concept analysis exploring a common multidisciplinary language. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:2504–19.

Livneh H, RF A. Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability: Marylan d:Aspen publishers; 1997.

Chouliara Z, Stephen K, Buchanan P. The importance of psychosocial assessment in dermatology: opening Pandora’s box? Dermatol Nurs. 2017;16(4):30–4.

Li L, Liu P, Li J, Xie HF, Kuang YH, Li J, et al. Psychosocial factors of chronic hand eczema. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2017;42:179–83.

Marron SE, Tomas-Aragones L, Navarro-Lopez J, Gieler U, Kupfer J, Dalgard FJ, et al. The psychosocial burden of hand eczema: data from a European dermatological multicentre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:406–12.

Krishna GS, Ramam M, Mehta M, Sreenivas V, Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Vitiligo impact scale: an instrument to assess the psychosocial burden of vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:205–10.

Richards HL. The psychosocial impact of psoriasis: implications for treatment, ProQuest Information & Learning; 2018.

Kouris A, Christodoulou C, Stefanaki C, Livaditis M, Tsatovidou R, Kouskoukis C, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial aspects in Greek patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:841–5.

Bidaki R, Majidi N, Moghadam Ahmadi A, Bakhshi H, Sadr Mohammadi R, Mostafavi SA, et al. Vitiligo and social acceptance. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:383–6.

Lakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. How does stigma affect people with psoriasis? Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:36–41.

Rosinska M, Rzepa T, Szramka-Pawlak B, Zaba R. Body image and depressive symptoms in person suffering from psoriasis. Psychiatr Pol. 2017;51:1145–52.

Nicholas MN, Gooderham MJ. Atopic dermatitis, depression, and Suicidality. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:237–42.

Lamb RC, Matcham F, Turner MA, et al. Screening for anxiety and depression in people with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary referral setting. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):1028–34.

Lakuta P, Przybyla-Basista H. Toward a better understanding of social anxiety and depression in psoriasis patients: the role of determinants, mediators, and moderators. J Psychosom Res. 2017;94:32–8.

Ayala F, Sampogna F, Romano GV, Merolla R, Guida G, Gualberti G, et al. The impact of psoriasis on work-related problems: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1623–32.

Chen YJ, Chen CC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Li CY, Hwang CY, et al. Increased risk of sexual dysfunction in male patients with psoriasis: A nationwide population- based follow- up study. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1212–8.

Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Living with psoriasis: prevalence of shame, anger, worry, and problems in daily activities and social life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:299–303.

Janowski K, Steuden S, Pietrzak A, Krasowska D, Kaczmarek L, Gradus I, et al. Social support and adaptation to the disease in men and women with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:421–32.

Chan MF, Chua TL, Goh BK, Aw CW, Thng TG, Lee SM. Investigating factors associated with depression of vitiligo patients in Singapore. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:1614–21.

Kwan Z, Bong YB, Tan LL, Lim SX, Yong ASW, Ch'ng CC, et al. Determinants of quality of life and psychological status in adults with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:443–51.

Dieris-Hirche J, Gieler U, Petrak F, Milch W, Te Wildt B, Dieris B, et al. Suicidal ideation in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: A German cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:1189–95.

Premkumar R, Kar B, Rajan P, Richard J. Major precipitating factors for stigma among stigmatized vitiligo and psoriasis patients with brown-black skin shades. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(5):703–5.

Kwan Z, Bong YB, Tan LL, Lim SX, Yong AS, Ch’ng CC, et al. Socioeconomic and sociocultural determinants of psychological distress and quality of life among patients with psoriasis in a selected multi-ethnic Malaysian population. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22:184–95.

Alpsoy E, Polat M, FettahlioGlu-Karaman B, Karadag AS, Kartal-Durmazlar P, YalCın B, et al. Internalized stigma in psoriasis: A multicenter study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:885–91.

Molina-Leyva A, Molina-Leyva I, Almodovar-Real A, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Naranjo-Sintes R, Jimenez-Moleon JJ. Prevalence and associated factors of erectile dysfunction in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and healthy population: A comparative study considering physical and psychological factors. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:2047–55.

Innamorati M, Quinto RM, Imperatori C, Lora V, Graceffa D, Fabbricatore M, Lester D, Contardi A, Bonifati C. Health-related quality of life and its association with alexithymia and difficulties in emotion regulation in patients with psoriasis. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;70:200–8.

Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Evaluating the effect of treatment persistence the economic Burden of moderate to severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the U.S. Department of Defense population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:654–63.

Kimball AB, Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, Guo J, Maeda-Chubachi T, Shen W, Bianchi MT. Understanding the relationship between pruritus severity and work productivity in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: sleep problems are a mediating factor. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(2):183–8.

Ahmed AE, Al-Dahmash AM, Al-Boqami QT, Al-Tebainawi YF. Depression, anxiety and stress among Saudi Arabian dermatology patients: cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16:e217–23.

Khoury LR, Danielsen PL, Skiveren J. Body image altered by psoriasis. A study based on individual interviews and a model for body image. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:2–7.

Lakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezinska-Wcislo L, Slomian A. Associations between site of skin lesions and depression, social anxiety, body-related emotions and feelings of stigmatization in psoriasis patients. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018;35:60–6.

Nayak PB, Girisha BS, Noronha TM. Correlation between disease severity, family income, and quality of life in psoriasis: A study from South India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:165–9.

Hebert AA, Stingl G, Ho LK, Lynde C, Cappelleri JC, Tallman AM, Zielinski MA, Frajzyngier V, Gerber RA. Patient impact and economic burden of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(12):2177–85.

Nazik H, Nazik S, Gul FC. Body image, self-esteem, and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:343–6.

Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, Roberts J. Relationship between psoriasis severity, clinical symptoms, quality of life and work productivity among patients in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:514–21.

Tee SI, Lim ZV, Theng CT, Chan KL, Giam YC. A prospective cross-sectional study of anxiety and depression in patients with psoriasis in Singapore. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1159–64.

Yano C, Saeki H, Ishiji T, Ishiuji Y, Sato J, Tofuku Y, et al. Impact of disease severity on work productivity and activity impairment in Japanese patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:736–9.

Schneider G, Heuft G, Hockmann J. Determinants of social anxiety and social avoidance in psoriasis outpatients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:383–6.

Geale K, Henriksson M, Schmitt-Egenolf M. How is disease severity associated with quality of life in psoriasis patients? Evidence from a longitudinal population-based study in Sweden. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):151.

Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Roberts J, Pike J, Sullivan E, Tsang Y, Karagiannis T. Impact of psoriasis flare and remission on quality of life and work productivity: a real-world study in the USA. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:7.

Pereira MG, Brito L, Smith T. Dyadic adjustment, family coping, body image, quality of life and psychological morbidity in patients with psoriasis and their partners. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19(3):260–9.

Chrostowska-Plak D, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Relationship between itch and psychological status of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e239–42.

Lewis-Beck C, Abouzaid S, Xie L, Baser O, Kim E. Analysis of the relationship between psoriasis symptom severity and quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis using structural equation modeling. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:199–205.

Sarhan D, Mohammed GFA, Gomaa AHA, Eyada MMK. Female genital dialogues: female genital self-image, sexual dysfunction, and quality of life in patients with vitiligo with and without genital affection. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016;42:267–6.

Molina-Leyva A, Almodovar-Real A, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Naranjo-Sintes R, Serrano-Ortega S, Jimenez-Moleon JJ. Distribution pattern of psoriasis affects sexual function in moderate to severe psoriasis: A prospective case series study. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2882–9.

Ji S, Zang Z, Ma H, et al. Erectile dysfunction in patients with plaque psoriasis: the relation of depression and cardiovascular factors. Int J Impot Res. 2016;28:96–100.

Ahmed A, Shah R, Papadopoulos L, Bewley A. An ethnographic study into the psychological impact and adaptive mechanisms of living with hand eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:495–501.

Brito L, da Graça Pereira M. Individual and family variables in psoriasis: A study with patients and partners. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa. 2012;28:171–9.

Koo J, Marangell LB, Nakamura M, Armstrong A, Jeon C, Bhutani T, et al. Depression and suicidality in psoriasis: review of the literature including the cytokine theory of depression. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1999–2009.

Egeberg A, Khalid U, Gislason GH, Mallbris L, Skov L, Hansen PR. Impact of depression on risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death in patients with psoriasis: A Danish Nationwide study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:218–21.

Zhu B, Cao C. Correlative research between stigma, social support and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Chin Nurs Res. 2016;30:3639–42.

Pichaimuthu R, Ramaswamy P, Bikash K, Joseph R. A measurement of the stigma among vitiligo and psoriasis patients in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:300–6.

Norreslet LB, Ebbehoj NE, Ellekilde Bonde JP, Thomsen SF, Agner T. The impact of atopic dermatitis on work life - a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:23–38.

Kwak Y, Kim Y. Associations between prevalence of adult atopic dermatitis and occupational characteristics. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23:e12554. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12554.

Cazzaniga S, Ballmer-Weber BK, Grani N, Spring P, Bircher A, Anliker M, et al. Medical, psychological and socio-economic implications of chronic hand eczema: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:628–37.

Mattila K, Leino M, Mustonen A, Koulu L, Tuominen R. Influence of psoriasis on work. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(2):208–11.

Levy AR, Davie AM, Brazier NC, et al. Economic burden of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Canada. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1432–40.

Itakura A, Tani Y, Kaneko N, Hide M. Impact of chronic urticaria on quality of life and work in Japan: results of a real-world study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:963–70.

Schmitt J, Küster D. Correlation between dermatology life quality index (DLQI) scores and work limitations questionnaire (WLQ) allows the calculation of percent work productivity loss in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307(5):451–3.

Nguyen CM, Beroukhim K, Danesh MJ, Babikian A, Koo J, Leon A. The psychosocial impact of acne, vitiligo, and psoriasis: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:383–92.

Rzepecki AK, McLellan BN, Elbuluk N. Beyond traditional treatment: the importance of psychosocial therapy in Vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(6):688–91.

Paul D, Kinsella L, Walsh O, Sweenry C, Timoney I, Lynch M, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psoriasis: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness. 2018;10(2):288–300.

Hashimoto K, Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Furukawa TA. Psychological and educational interventions for atopic dermatitis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Chang. 2017;34:48–65.

Van Beugen S, Ferwerda M, Spillekom-van Koulil S, Smit JV, Zeeuwen-Franssen ME, Kroft EB, et al. Tailored therapist-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral treatment for psoriasis: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85:297–307.

Shah R, Hunt J, Webb TL, Thompson AR. Starting to develop self-help for social anxiety associated with vitiligo: using clinical significance to measure the potential effectiveness of enhanced psychological self-help. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:332–7.

Bundy C, Pinder B, Bucci S, Reeves D, Griffiths CE, Tarrier N. A novel, web-based, psychological intervention for people with psoriasis: the electronic targeted intervention for psoriasis (eTIPs) study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:329–36.

Zill JM, Christalle E, Tillenburg N, Mrowietz U, Augustin M, Härter M, Dirmaier J. Effects of psychosocial interventions on patient-reported outcomes in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018.

Nagarajan P, Thappa DM. Effect of an educational and psychological intervention on knowledge and quality of life among patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9(1):27–32.

Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Wollenberg A, Abraham S, Plank-Habibi S, Schnopp C, et al. Effects of structured patient education in adults with atopic dermatitis: multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:845–53.

Jha A, Mehta M, Khaitan BK, Sharma VK, Ramam M. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychosocial stress in vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(3):308–10.

Keyworth C, Nelson PA, Bundy C, Pye SR, Griffiths CEM, Cordingley L. Does message framing affect changes in behavioural intentions in people with psoriasis? A randomized exploratory study examining health risk communication. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23:763–78.

Ahmed A, Steed L, Burden-Teh E, Shah R, Sanyal S, Tour S, Dowey S, Whitton M, Batchelor JM, Bewley AP. Identifying key components for a psychological intervention for people with vitiligo - a quantitative and qualitative study in the United Kingdom using web-based questionnaires of people with vitiligo and healthcare professionals. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2275–83.

Ormerod E, Bale T, Stone N. Psoriasis direct service: an audit and review. Dermatol Nurs. 2017;16(1):45–9.

Gionfriddo MR, Pulk RA, Sahni DR, Vijayanagar SG, Chronowski JJ, Jones LK, et al. ProvenCare-psoriasis: A disease management model to optimize care. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:3.

Acknowledgements

N/A

Funding

This work was supported by Nursing Branch of China Research Hospital (NBCRH), which provided financial support during the search and screening of the literatures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XJZ and APW designed the research protocol, performed and analyzed the research. XJZ and LF performed the search. Where questions arose, TYS, JZ and HX advised on article inclusion. TYS and JZ designed and tested the extraction forms. XJZ and APW designed the Tables. XJZ wrote the manuscript. XJZ, APW, TYS, JZ, HX and DQW read and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We strictly followed the standards of scoping review. There were no human participants and therefore no ethical approvals were not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Xj., Wang, Ap., Shi, Ty. et al. The psychosocial adaptation of patients with skin disease: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 19, 1404 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7775-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7775-0