Abstract

Background

The mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) is a marker that reflects the clinical outcome of cancer treatment. MIR as a prognostic marker is more accessible when compared with long-term follow-up survival surveys. Theoretically, countries with good health care systems would have favorable outcomes for cancer; however, no report has yet demonstrated an association between gallbladder cancer MIR and the World’s Health System ranking.

Methods

We used linear regression to analyze the correlation of MIRs with the World Health Organization (WHO) rankings and total expenditures on health/gross domestic product (e/GDP) in 57 countries selected according to the data quality.

Results

The results showed high crude rates of incidence/mortality but low MIR in more developed regions. Among continents, Europe had the highest crude rates of incidence/mortality, whereas the highest age-standardized rates (ASR) of incidence/mortality were in Asia. The MIR was lowest in North America and highest in Africa (0.40 and 1.00, respectively). Furthermore, favorable MIRs were correlated with good WHO rankings and high e/GDP (p = 0.01 and p = 0.030, respectively).

Conclusions

The MIR variation for gallbladder cancer is therefore associated with the ranking of the health system and the expenditure on health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) and extra-hepatic duct cholangiocarcinoma are rare diseases with age standardized incidence rates of around 2 to 3 per 100,000 populations in both gender separately worldwide [1, 2]. GBC is a highly fatal malignancy, with a 5-year survival rate around 13%, and the only effective treatment is early diagnosis [3, 4]. GBC has a prominent geographic variability associated with the prevalence of risk factors [5] such as cholelithiasis [6]. GBC has a higher incidence in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia, according to previous studies [5]. GBC has other known characteristics apart from this geographic issue, such as age [7], race, and gender [8], suggesting that the age-standardized rate (ASR) is more reliable than the crude rate as a method for disease evaluation of GBC.

The known risk factors of GBC are gallbladder disease (including gallstones [6], porcelain gallbladder [9], and gallbladder polyps [10]); chronic inflammation of the bile duct (e.g., primary sclerosing cholangitis [11], choledochal cysts, and abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junctions [12]); and chronic bacterial infections (e.g., Salmonella [13] and Helicobacter infections [14]) [15]. In terms of these risk factors, congenital abnormalities and chronic bacterial infections are common mainly in low socioeconomic areas, whereas high-fat diets and Caucasian ethnicity [16] increase the possibility of GBC in high socioeconomic countries.

The only treatment that provides a good outcome for GBC is early curative resection. The 5-year mortality rate is around 50% in cases with peri-muscular connective tissue involvement [17], regardless of the treatment choice of surgical resection or adjuvant chemotherapy. The poor response of current chemotherapy regimens means that once GBC invades beyond the gallbladder, the outcome becomes poor and the median survival is only around 3 years [4, 18]. Chemoradiotherapy is another approach for treatment of systemically spreading GBCs, but no randomized trials have yet directly compared the effectiveness of chemotherapy alone versus concomitant chemoradiotherapy [19].

Technical and equipment improvements suggest that health care systems may be able to improve early lesion detection. Better socioeconomic conditions can prevent delays in surgical cholecystectomy, thereby avoiding the extra-gallbladder spread of GBC. We considered that the mortality-to-incidence (MIR) ratio for GBC would be low in a country with a good health care system, as a similar concept has recently been confirmed for prostate and colon cancers [20,21,22,23]. The aim of the present study was to clarify the association between World Health Organization (WHO) ranking, geographic region, total expenditure on health/gross domestic product (GDP; e/GDP), and the ASR of GBC incidence and mortality. Our results provide an overview of the MIR and health disparities worldwide for GBC.

Methods

The data acquisition protocol was described previously [20]. In brief, the cancer incidence and mortality data were obtained from the GLOBOCAN 2012 database, which presented estimates for 2012. The crude rate and ASR are multiplied by 100,000 (cases per 100,000 populations). The database is maintained by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (http://gco.iarc.fr/). The WHO rankings are the World Health Organization’s ranking of the health systems based on an index of factors including health, responsiveness, and fair financial contribution. The health expenditure and life expectancies were obtained from the World Health Statistics 2015 of WHO.

The GLOBOCAN 2012 database contains information for 184 countries. We excluded countries that lacked WHO ranking data (22 countries) or that had a low availability level of data (i.e., a ranking of E to G for incidence or a ranking of 4 to 6 for mortality; 105 countries). Ultimately, 57 countries were used for our analyses. The MIR was defined previously as the ratio of the crude rate of mortality to the incidence [23].

The method used for statistical analysis was described previously [20]. We evaluated the association between the MIRs and variants via linear regression using SPSS statistical software version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Scatter plots were produced using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

The distribution of incidence and mortality numbers/rates in gallbladder cancer according to regions

The incidence/mortality numbers, crude rates, ASR, and MIRs are listed in Table 1. The survey included 178,101 incidences and 142,823 mortalities worldwide. The more developed regions had higher crude rates of incidence/mortality, but favorable ASR and MIRs, when compared with the less developed regions. In the categories of WHO regions, the WHO Western Pacific region had the highest number, crude rates, and ASR of incidence/mortality. However, when we grouped the countries via continent, the highest crude rates of incidence/mortality were in Europe and the highest ASR of incidence/mortality was in Asia. In both categories, Africa had the highest MIR and the WHO Americas region and North America had the lowest MIR.

The World Health Organization ranking and total health expenditure are correlated with the mortality-to-incidence ratios in gallbladder cancer

The data for 57 selected countries are summarized in Table 2. The mean e/GDP was 8.0%, with a standard deviation of 2.6 (ranging from 4.0% [Malaysia and Fiji] to 17.0% [United States of America]). Among the 57 countries, Japan had the highest incidence and mortality number for GBC. For both the incidence and mortality rates, Japan had the highest incidence and mortality crude rates and Chile had the highest incidence and mortality ASR. Five countries had MIR values greater than or equal to 1.00, including Sweden (1.23), Estonia (1.12), Egypt (1.00), the Republic of South Africa (1.00), and Oman (1.00).

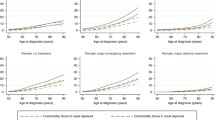

The association between crude rate/age-standardized rate of incidence/mortality and the WHO ranking or e/GDP is illustrated in Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2. No significant association was noted, except between the e/GDP and the crude rate of incidence (p = 0.031, Additional file 1: Figure S2A). The favorable MIRs of 57 countries were significantly associated with good WHO ranking and high e/GDP (R2 = 0.176, p = 0.001; R2 = 0.083, p = 0.030, respectively, Fig. 1).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the correlation of incidence, mortality, and MIRs for GBC with WHO rankings and total expenditures on health/GDP. A correlation between MIR and health care disparities was confirmed previously for many cancers [20, 23]. Our analysis showed that the more developed regions have higher crude rates of incidence and mortality but favorable ASR and MIRs when compared with the less developed regions. The developed regions and countries have greater numbers of elderly people and older age is one important risk factor of GBC; consequently, the crude rates of incidence and mortality were higher in the more developed regions, but the condition was reversed for ASR and MIRs. The geographic continent analysis revealed that the WHO Western Pacific region and Asia had the highest ASR of incidence and mortality for GBC and these results were similar to those of previous studies of geographic regions [5, 24] published decades ago. Both the WHO America region and North America showed a median ASR of incidence and the lowest age-standardized mortality and MIRs. These results imply an importance of economic level and e/GDP in GBC prognosis.

The best treatment choice is early diagnosis, so screening programs and high probability population for GBC have been established in some studies [25, 26]. The availability of precision instruments and experienced physicians are known key factors for the early diagnosis of GBC. Africa had the lowest crude rates and ASR of incidence/mortality, but the highest MIR around the world.

The WHO ranking and e/GDP showed no significant correlations with the crude rate and ASR of incidence/mortality, except for the crude rate of incidence. We found an association between a higher e/GDP and a higher crude rate of incidence for GBC in our analysis. We believe that the higher e/GDP countries have better or more frequent screening programs, which lead to more GBC diagnoses. Furthermore, the favorable MIRs of 57 countries are significantly associated with good WHO ranking and high e/GDP (R2 = 0.176, p = 0.001; R2 = 0.083, p = 0.030, respectively, Fig. 1).

This study has some limitations. First, many countries, and especially those in the least developed areas in the world, do not participate in the WHO, and this may influence the impact of total e/GDP on GBC incidence. Second, the ethnicity, geographic region, and national health insurance issues (especially for e/GDP) could not be fully analyzed in our study, and these issues may add some bias to our study. Third, the use of MIR for predicting disease outcome has many limitations, since MIR was calculated from the cross-sectional data of mortality and incidence for a certain period causing different patients calculated in the incidence and mortality. MIR would not substitute for prognostic data from long-term follow up or from a cohort study. Forth, we excluded countries with relatively poor or unknown data quality which changes the distribution of countries according to the regions or continents. We analyzed the main results without country selection, the conclusion remains unchanged. The favorable MIRs of all countries were significantly associated with good WHO ranking and high e/GDP (R2 = 0.309, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.118, p < 0.001, respectively, Additional file 1: Figure S3). Other limitations include the lack of detailed information about the disease clinical parameters, health care facilities or policies, socioeconomic determinant, and confounding factors of cancer risks. Despite these limitations, MIR appears to provide more accessible data when compared with long-term follow up survival surveys.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the MIRs of GBC showed a significant correlation with the WHO ranking and e/GDP in this study. We successfully demonstrated that MIRs could reflect the health care disparities in GBC worldwide and could explain the differences in crude rates and ASR of incidence and mortality between WHO region categories and geographic continents.

Availability of data and materials

All the data were obtain from global statistic of GLOBOCAN (http://gco.iarc.fr/). The database of GLOBOCAN 2012 is closed while this manuscript was under revision since the updated database is released. The database might be available upon request to the IARC.

Abbreviations

- ASR:

-

age-Standardized rate

- e/GDP:

-

Total expenditures on health/gross domestic product

- GBC:

-

Gallbladder cancer

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- MIR:

-

Mortality-to-incidence ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Are C, Ahmad H, Ravipati A, Croo D, Clarey D, Smith L, Price RR, Butte JM, Gupta S, Chaturvedi A, et al. Global epidemiological trends and variations in the burden of gallbladder cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(5):580–90.

Gatto M, Bragazzi MC, Semeraro R, Napoli C, Gentile R, Torrice A, Gaudio E, Alvaro D. Cholangiocarcinoma: update and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(4):253–60.

Hickman L, Contreras C. Gallbladder Cancer: Diagnosis, Surgical Management, and Adjuvant Therapies. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99(2):337–55.

Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(7):1591–602.

Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Wang BS, Shen MC, Zhang BH, Niwa S, Chen J, et al. Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(11):1577–82.

Konstantinidis IT, Deshpande V, Genevay M, Berger D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Tanabe KK, Zheng H, Lauwers GY, Ferrone CR. Trends in presentation and survival for gallbladder cancer during a period of more than 4 decades: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg. 2009;144(5):441–7 discussion 447.

Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil D, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, D'Angelica M, Dematteo RP, Blumgart LH, O'Reilly EM. Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC). J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(7):485–9.

Schnelldorfer T. Porcelain gallbladder: a benign process or concern for malignancy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(6):1161–8.

Okamoto M, Okamoto H, Kitahara F, Kobayashi K, Karikome K, Miura K, Matsumoto Y, Fujino MA. Ultrasonographic evidence of association of polyps and stones with gallbladder cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(2):446–50.

Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, Nagorney DM, Boberg KM, Shneider B, Gores GJ, American Association for the Study of liver D. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):660–78.

Elnemr A, Ohta T, Kayahara M, Kitagawa H, Yoshimoto K, Tani T, Shimizu K, Nishimura G, Terada T, Miwa K. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction without bile duct dilatation in gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48(38):382–6.

Nagaraja V, Eslick GD. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the relationship between chronic Salmonella typhi carrier status and gall-bladder cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(8):745–50.

Murata H, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Fu HY, Tanimura H, Tsujimoto M, Matsuura N, Kawano S, Hori M. Helicobacter bilis infection in biliary tract cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):90–4.

Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, Yadav A, Kumar A. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: recent update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(22):3978–98.

Scott TE, Carroll M, Cogliano FD, Smith BF, Lamorte WW. A case-control assessment of risk factors for gallbladder carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(8):1619–25.

Shindoh J, de Aretxabala X, Aloia TA, Roa JC, Roa I, Zimmitti G, Javle M, Conrad C, Maru DM, Aoki T, et al. Tumor location is a strong predictor of tumor progression and survival in T2 gallbladder cancer: an international multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):733–9.

Ben-Josef E, Guthrie KA, El-Khoueiry AB, Corless CL, Zalupski MM, Lowy AM, Thomas CR Jr, Alberts SR, Dawson LA, Micetich KC, et al. SWOG S0809: a phase II intergroup trial of adjuvant Capecitabine and gemcitabine followed by radiotherapy and concurrent Capecitabine in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(24):2617–22.

Kim Y, Amini N, Wilson A, Margonis GA, Ethun CG, Poultsides G, Tran T, Idrees K, Isom CA, Fields RC, et al. Impact of chemotherapy and external-beam radiation therapy on outcomes among patients with resected gallbladder Cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(9):2998–3008.

Chen SL, Wang SC, Ho CJ, Kao YL, Hsieh TY, Chen WJ, Chen CJ, Wu PR, Ko JL, Lee H, et al. Prostate Cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios Are associated with Cancer care disparities in 35 countries. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40003.

Cordero-Morales A, Savitzky MJ, Stenning-Persivale K, Segura ER. Conceptual considerations and methodological recommendations for the use of the mortality-to-incidence ratio in time-lagged, ecological-level analysis for public health systems-oriented cancer research. Cancer. 2016;122(3):486–7.

Sunkara V, Hebert JR. The application of the mortality-to-incidence ratio for the evaluation of cancer care disparities globally. Cancer. 2016;122(3):487–8.

Sunkara V, Hebert JR. The colorectal cancer mortality-to-incidence ratio as an indicator of global cancer screening and care. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1563–9.

Strom BL, Soloway RD, Rios-Dalenz JL, Rodriguez-Martinez HA, West SL, Kinman JL, Polansky M, Berlin JA. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer. An international collaborative case-control study. Cancer. 1995;76(10):1747–56.

Zhou D, Wang JD, Yang Y, Yu WL, Zhang YJ, Quan ZW. Individualized nomogram improves diagnostic accuracy of stage I-II gallbladder cancer in chronic cholecystitis patients with gallbladder wall thickening. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15(2):180–8.

Tan CH, Lim KS. MRI of gallbladder cancer. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19(4):312–9.

Acknowledgements

The results were presented at APDW 2018 (EE-0207; PE-0029, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14483).

Funding

This work was supported by grant from the Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (CSH-2013-A-027). The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, in the collection of data, analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, WWS; Data curation, CMP and HLL; Formal analysis, MCT, HYC and TWY; Investigation, CCW, MCTi and SCW; Supervision, CCL and WWS; Writing original draft, CCW, MCT and SCW; Writing – review & editing, CCL and WWS. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interest. All authors are employees of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The association between the World Health Organization rankings and the crude rates of (A) incidence, and (B) mortality; the ASR of (C) incidence, and (D) mortality. Figure S2. The association between the total expenditures on health/GDP and the crude rates of (A) incidence, and (B) mortality; the ASR of (C) incidence, and (D) mortality. Figure S3. The (A) World Health Organization rankings (N = 142) and (B) total expenditures on health/GDP (N = 139) are significantly associated with the MIR in gallbladder cancer under investigation without country selection. (DOCX 739 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, CC., Tsai, MC., Wang, SC. et al. Favorable gallbladder cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios of countries with good ranking of world’s health system and high expenditures on health. BMC Public Health 19, 1025 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7160-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7160-z