Abstract

In 2017 Public Health England were asked to assist with investigating why 1-year cancer survival rates appeared lower than expected in a local area. We identified 50 premature deaths that surveillance data suggested we would not expect. These deaths highlighted a gap in recognising and responding to this kind of systematic non communicable disease (NCD) outcome variation. We hypothesise that the lack of a universally agreed systematic response to variations is not only counter-intuitive, but wholly unacceptable where non-communicable diseases (NCDs) rather than infectious diseases have become the leading causes of illness and death worldwide. In the United Kingdom (UK) alone over 89% of mortality in 2014 was attributable to NCDs. We argue that a new approach is urgently needed to turn the curve on NCD outcome variation to protect and improve the public’s health. We set out a definition of an NCD “incident” and propose a phased approach that could be used to respond to local variation in NCD outcomes.

Establishing parity of response for local variations in NCD outcomes and CD control is critically important. Although evidence shows that prevention and early intervention will make the biggest difference to NCD incidence, collective local whole health economy response, exploiting the wealth of surveillance data in real time, needs to be at the heart of responding to variations in NCD outcomes at a population level. We argue that local and national public health agencies should mandate a standardised ‘incident’ response to significant changes in outcomes from NCD to mitigate and reduce the loss of quality life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key messages

3 things we want to happen:

-

Agencies to have parity of response for local variations in NCD outcomes and CD control.

-

To build body of evidence about how proposed approach works across investigations into different NCD responses.

-

Make legislative changes to PH act to reflect the growing need to better protect the public from variations in NCD outcomes.

Background

What happens if there are 50 unexpected deaths in a 5 year period attributable to a communicable disease (CD)? In a country with a developed public health system this scenario is almost inconceivable as actions would have been taken to prevent these deaths soon after the incident was recognised. Resources are quickly mobilised; supported by systematic surveillance, well-practiced incident response systems and consensus of what constitutes an incident/ outbreak; all of which is mandated in national [1, 2] and international legislation [3].

Now consider the same scenario of 50 premature deaths attributable to a non-communicable disease (NCD), where surveillance data shows we would not otherwise expect this (Fig. 1). There is currently no accepted standard response to such an incident.

Variation in 1-year lung cancer survival rates between a CCG and the England average [24]

There are two inherent prejudices between NCD and CD control that may have limited previous thinking on the parity of approach:

-

1.

It can be argued that NCD outcome variation can only harm relatively small numbers of people affected at local level over short periods of time whereas localised CD outbreaks can escalate exponentially, and in extreme cases turn into national and international outbreaks harming thousands of people, trade [3] and generating high profile media coverage and, public concern if not rapidly controlled.

-

2.

The aetiologies of NCDs are wide ranging, complex, and, lead time from exposure to diagnosis can be decades [4,5,6]. These are often chronic health issues for individuals as opposed to acute CDs. This may mask that variation in outcomes for NCDs may be an acute issue for a local health system.

The lack of a systematic response to NCDs may have increased variation in outcomes that is readily observed within populations [7,8,9]. The failing of health and public health systems to effectively and efficiently tackle variation in outcomes [6] is at odds with the significant achievements public health agencies have demonstrated in reducing the burden of CDs [10].

Main text

We propose six changes, necessary to remove the inherent prejudices and test our proposals to achieve parity of response with the management of outbreaks of CDs.

CHANGE 1: Remove the ‘strategy paradox’ for NCDs

Long term NCD strategies for international or national geographies guide the implementation of approaches to improve NCD outcomes. In England successive plans have been developed to tackle the major NCDs. Paradoxically, despite their aims, these strategies fail to address or respond to locally changing patterns of disease. Referring back to our opening scenario, and Fig. 1, one of the most recent national plans is the Cancer Strategy in England. This has the aim of “improving survival rates and saving thousands of lives” [11] and includes 96 recommendations and the formation of a multitude of working groups. However there is no recommendation for systematic surveillance, control systems, and, response to reduce adverse changes in local cancer outcomes. Unlike CD guidelines [12], NCD strategies are not prescriptive or do not mention the steps local areas should take to respond to variation in outcomes. We argue that these are fundamental to achieve parity with CD control.

CHANGE 2: Translate surveillance data on NCDs into meaningful local action

In CD management, streamlined passive surveillance by diagnostic and public health laboratories, under the leadership of a national public health agency, has been the hallmark for improving responses [1, 2] and reducing burden. This system, coupled with local intelligence, often leads into the initiation of further investigations e.g. active and enhanced surveillance along with incident/outbreak identification and response. It is an approach that is supported by the standards set out in the International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005 [3].

In the United Kingdom (UK), variations in NCD outcomes are observed in a number of Government [13], National Health Service (NHS) [14] and, public health [15] sources. To combine and translate NCD surveillance data into meaningful local action, the information needs to be understood from a whole local health economy perspective so that assumptions can be challenged, root causes understood, actions allocated and, ultimately step changes in improvements made. It is unsatisfactory to assume that population demography is the only cause of variation without fully testing this hypothesis but at present, no centrally co-ordinated effort has been made to standardise an approach. In our lung cancer investigation alone, we examined six datasets published by four separate agencies. We recognise that additional datasets would be useful but are neither publicly available nor standardised.

We acknowledge that globally, surveillance systems in some low and middle income countries are less well established. Whilst this will hinder progress on this step change in the short term, the call for parity of approach for NCD incidents (in comparison to CD incidents) is applicable as health system architects consider how to design and embed surveillance systems to understand and improve public health in the future.

CHANGE 3: Develop accountability and ownership of local NCD responses

The ‘who is responsible for action’ related to improving NCD outcome and reducing variation can also result in complexity. For example, as an output of the Cancer Strategy in England [12], several recommendations focussed on increasing data availability, ensuring audit of deaths related to treatment and, holding local health bodies in England to account for 1-year survival outcomes. At the time this was heralded as a “transformational” change for cancer services. It was regarded as a driver “for Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to work across all relevant organisations … to improve survival rates” [16]. However, this performance management approach, in which there is the potential for a culture of either commissioner or provider blame [17, 18], is at odds with the culture of a CD incident response [12]. In the latter, the accountability for patient outcomes (outside of a specific clinical setting) are not inherently owned by one organisation of the NHS, and the system response is collective, led by public health specialists and is focused on improving outcomes and quality of care [1, 12]. We believe that local accountability and ownership of NCD responses should be embedded into developing place based health systems and recognise the opportunity that the ongoing emergence of new care models provides to achieve this.

CHANGE 4: Agree a common definition of a NCD ‘incident’

Unlike with CD [1, 2] there is lack of clarity in both national strategies and the literature about what might constitute an ‘incident’ relating to variations in NCD outcomes. A working definition would help address the segregation and silo working [17, 18] currently inherent in NCD response and provide a common language to facilitate collaborative action (Table 1).

In defining a NCD “incident” the focus is on understanding changes in outcomes in a local area over time. Solely having high rates of mortality from lung cancer in comparison to an average would not qualify, nor would having a historically higher than expected rate of lung cancer in the local area. Instead, there would need to be a significant and sustained change in (e.g. lung cancer) outcomes in a defined area over a successive time period.

Additionally, as stated in Table 1 with the phrase “potential for single cause or focus of variation”, there would need to the possibility of a common origin of variation for changes in NCD outcomes to be recognised as an “incident”. Potential foci could be common demographics of patients affected, a common healthcare organisation or service, a specific pathway of care or even potentially the same healthcare professionals involved in delivering care. This would be necessary to warrant public health investigation given the opportunity cost and potential unintended consequences of investigating poorly defined NCD incidents.

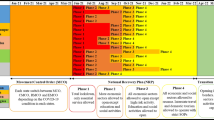

CHANGE 5: Implement a standardised incident control response to investigate NCD outcome variation

Once we have defined an NCD incident, how do we respond rapidly, locally? We argue that the response could take the same phased approach as a CD response (Table 2) and that lessons can be adopted from the standard guidelines used by health protection teams across the UK [12]. It is suggested that the leadership and oversight of this should be owned by a statutory body.

Defining standard, evidence informed tools that can be used by incident control leads and stakeholder partners to ensure control methods are employed in a timely fashion to minimise the impact of variation in NCD outcomes should be a priority. The authors recognise that the decision to formally end an NCD incident response is not yet defined; further work is needed to understand the necessary pre-requisites.

CHANGE 6: Consider legislative response to ensure parity for NCDs

In the UK the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984 [1] enshrined in law the requirement for a response to outbreaks of infections. This resulted in successive guidance on standards, shaped by historical failures, for the recognition, declaration, team response, investigation, control, communication and, end of incident [12].

The call for an incident control team meeting, or its equivalent, is not routine practice or a statutory responsibility in managing variation in NCD outcomes. This can result in de-prioritisation of the issues amongst stakeholders across the health sectors, which further exacerbates the population health risk. But, merely having a statutory duty may not be enough. The NHS has a statutory “duty” to “consider” reducing health inequality [19] but so far this has not, as yet, resulted in an entirely equitable system [20]. Considering need for legislative parity to mandate robust surveillance and mechanisms for response to variation in NCD outcomes is essential if society is to get serious about responding to incidents of NCD.

Discussion

In 2013, the Department of Health (as it was at that time) published the “Living Well for Longer…” policy paper. Within this, Jeremy Hunt, (Secretary of State for Health at the time) called on “all those involved across the health and care system and beyond” to “play their part and work together” … “to determine what they should be doing to support their local communities to live longer, healthier lives” [21]. Jeremy Hunt stated it was “time to be bold and ambitious for health”. Despite efforts over the last 6 years to improve the transparency of data [22] and develop new models of health and care delivery [23], we argue that without concentrated effort and resource to define an NCD incident and standardise a response using evidence informed tools we will not be able to achieve the great strides in health outcome improvements for NCD that have been accomplished by our counterparts working in CD control.

Conclusion

The morbidity, mortality and health inequalities related to NCD are increasing both domestically and globally. Whilst evidence shows that prevention and early intervention will make the biggest difference to NCD incidence, we believe that collective local whole health economy response, exploiting the wealth of surveillance data in real time, needs to be at the heart of responding to variations in NCD outcomes. This requires a cultural shift in historical approaches. We recognise that the time frame for defining and hence responding to an NCD incident is ambiguous at present. However, as highlighted in our recent investigation of variation in 1 year survival post cancer diagnoses, each year of delayed or ‘slow burn’ investigation will affect the survival and outcomes of a current cohort in the short and longer term. We argue that the ambition should therefore be for local and national public health agencies to determine their interpretation of ‘significant and sustained’ changes in population outcomes from NCD and mandate a standardised ‘incident’ response to mitigate and reduce the loss of quality life. The development of evidence-informed and pragmatic guidelines are required to standardise this approach and test its merit. Additionally, the specialist workforce required to make this step change must be considered. It may be sensible to initially focus on how definitions and guidance could look for such ‘incidents’ related to the main causes of premature death, perhaps CVD and cancer. We welcome suggestions to develop the definition for “NCD incident and response” to ensure that we can collectively rise to the challenge of protecting our patients, and populations from variations in outcomes from NCD.

Abbreviations

- CCG:

-

Clinical Commissioning Groups

- CD:

-

Communicable disease

- ICT:

-

Incident Control Team

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable disease

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- OCT:

-

Outbreak Control Team

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Legislation.gov.uk [Internet]. Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984 chp. 22; c1984 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/22.

Legislation.gov.uk [Internet]. The Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010 no. 659; c2010 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/659/contents/made.

World Health Organisation (WHO) [Internet]. International Health Regulations (2005) Second edition. Available at: http://www.who.int/ihr/publications/9789241596664/en/.

World Health Organisation (WHO) [Internet]. Noncommunicable diseases. [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

World Health Organisation (WHO) [Internet]. Non Communicable Disease Country Profiles; c2016 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/gbr_en.pdf.

World Health Organisation (WHO) [Internet]. Time to deliver. Report on the WHO Independent High-Level Commission on Noncommunicable Diseases. [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272710/9789241514163-eng.pdf?ua=1.

Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Williams J, et al. The epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK 2014. BMJ Heart. 2015;101:1182–9 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://heart.bmj.com/content/101/15/1182.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Statistical bulletin: Geographic patterns of cancer survival in England: Adults diagnosed 2003 to 2010 and followed up to 2015. Cancer survival estimates for England by NHS Region, Cancer Alliance, Sustainability and Transformation Plan. [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/geographicpatternsofcancersurvivalinengland/adultsdiagnosed2003to2010andfollowedupto2015

Care Quality Commission (CQC) [Internet]. The state of care in mental health services 2014 to 2017. [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20170720_stateofmh_report.pdf.

Public Health Achievements of the Twentieth Century. In: Pencheon D, Guest C, Melzer D, Muir Gray JA. Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice, Introduction to Section 4. Oxford: OUP: 178.

National Health Service (NHS) England [Internet]. Achieving world-class cancer outcomes: a strategy for England 2015–2020; c2016 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/achieving-world-class-cancer-outcomes-a-strategy-for-england-2015-2020/

Public Health England (PHE) [Internet]. Communicable Disease Incident Management Operational guidance. London: PHE; 2014 [cited 2019 Apr 30]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/communicable-disease-outbreak-management-operational-guidance.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) [Internet]. Statistical bulletins; c2017 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/atoz

National Health Service (NHS) digital [Internet]. Data and information; c2017 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/article/190/Data-and-information

Public Health England (PHE) [Internet]. Public Health Profiles; c2016 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/

All Party Parliamentary Group on Cancer (APPGC). One Year Cancer Survival Rates: Measuring Progress. Macmillan Cancer Support; 2015 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/APPGC%20-%20Measuring%20Progress_tcm9-291260.pdf

Ham, C. Reforming the NHS from within Beyond hierarchy, inspection and markets. London: Kings Fund; 2014 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/reforming-the-nhs-from-within-kingsfund-jun14.pdf

Davies HTO, Nutley SM, Mannion R. Organisational culture and quality of health care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2000;9:111–9.

National Health Service in England (NHSE) [Internet]. Challenging Health Inequalities. [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/challenging-health-inequalities/.

Nur U, Quaresma M, De Stavola B, et al. Inequalities in non-small cell lung cancer treatment and mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:985–92.

Department of Health (DH) [Internet]. Living Well for Longer: A call to action to reduce avoidable premature mortality. [cited 2019 Feb 18]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/181103/Living_well_for_longer.pdf.

Public Health England (PHE) [Internet]. Public Health Outcomes Framework. [cited 2019 Feb 18]. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/public-health-outcomes-framework

National Health Service in England (NHSE) [Internet]. Integrated Care Systems. [cited 2019 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/integrated-care-systems/

Office for National Statistics (ONS) [Internet]. Statistical bulletin: Index of cancer survival for Clinical Commissioning Groups in England: adults diagnosed 1999 to 2014 and followed up to 2015; c2016 [cited 2018 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/indexofcancersurvivalforclinicalcommissioninggroupsinengland/adultsdiagnosed1999to2014andfollowedupto2015

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There has been no funding to write this manuscript: no-one has prompted or paid us to write this paper or collect, analyse and interpret the lung cancer data that informed the concept.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset on variation in 1 year lung cancer survival which was analysed to inform the central argument of this debate article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK, MD, BA and CB have all been involved in the local response to an issue of NCD variation in outcomes in either the East Midlands or the North East. JK and MD proposed the ideas presented and drafted the article. BA and MK commented on drafts and supported development. JMJ and CB were consulted and suggested significant revisions. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. JK had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

All authors are currently employed by or have an honorary contract with Public Health England (PHE). JK is employed by Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. MK is PHE Centre Director lead for health protection including communicable disease response in England.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Knight, J., Day, M., Mair-Jenkins, J. et al. Responding to sustained poor outcomes in the management of non-communicable diseases (NCDs): an “incident control” approach is needed to improve and protect population health. BMC Public Health 19, 580 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6881-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6881-3