Abstract

Background

Child growth stunting remains a challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, where 34% of children under 5 years are stunted, and causing detrimental impact at individual and societal levels. Identifying risk factors to stunting is key to developing proper interventions. This study aimed at identifying risk factors of stunting in Rwanda.

Methods

We used data from the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2014–2015. Association between children’s characteristics and stunting was assessed using logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 3594 under 5 years were included; where 51% of them were boys. The prevalence of stunting was 38% (95% CI: 35.92–39.52) for all children. In adjusted analysis, the following factors were significant: boys (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.25–1.82), children ages 6–23 months (OR 4.91; 95% CI 3.16–7.62) and children ages 24–59 months (OR 6.34; 95% CI 4.07–9.89) compared to ages 0–6 months, low birth weight (OR 2.12; 95% CI 1.39–3.23), low maternal height (OR 3.27; 95% CI 1.89–5.64), primary education for mothers (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.25–2.34), illiterate mothers (OR 2.00; 95% CI 1.37–2.92), history of not taking deworming medicine during pregnancy (OR 1.29; 95%CI 1.09–1.53), poorest households (OR 1.45; 95% CI 1.12–1.86; and OR 1.82; 95%CI 1.45–2.29 respectively).

Conclusion

Family-level factors are major drivers of children’s growth stunting in Rwanda. Interventions to improve the nutrition of pregnant and lactating women so as to prevent low birth weight babies, reduce poverty, promote girls’ education and intervene early in cases of malnutrition are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2016, an estimated 155 million children worldwide were stunted (defined as being too short for their age); over one-third of them resided in Africa [1, 2]. Currently, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), 34% of children aged less than five years are stunted and the burden of stunting is most prevalent in the Eastern African region (37% stunted) [2]. Growth stunting is considered an important indicator of child health inequalities [3, 4]. It can be caused by several factors in both pre- and post-natal phases of development, some of these factors include poor nutrition, infectious diseases, and household environment [5]. A global review of stunting in low- and middle-income countries identified growth restriction in-utero and lack of access to sanitation as the main drivers of stunting [6]. Thus early interventions are necessary to prevent stunting; after the first two years of life, stunting is often irreversible [7].

Several studies have demonstrated the negative and long-term impacts of stunting on early childhood development such as poor performance at school and low productivity when they reach their working age [8, 9]. Stunted children remain behind their non-stunted peers later in life [10]. Rwanda lost over US$48 million of its 2012 GDP from an estimated three million people (49%) of working age (16–64 years old) who suffered from stunting as children [11]. Repetition of grades and school dropout rates among stunted children were also associated with significant economic losses for the education system, families, and the labor market. Stimulation interventions can improve cognitive outcomes in children who are stunted; however, these interventions are insufficient for eliminating the negative effects of stunting [10].

More than one in five child deaths were attributed to under-nutrition in 2012 [11]. Hence, the government of Rwanda has developed a plan to eliminate all forms of malnutrition with a special focus on growth stunting [12, 13]. Under this plan, numerous interventions to improve maternal and child nutrition have been implemented, e.g., micronutrient supplementation for both the mother and her child, deworming, a nationwide campaign on the first 1000 days of a child’s life to change behaviors around maternal care and maternal and child nutrition, timing and appropriate diet for complementary feeding, child care and hygiene [14]. While the proportion of stunted Rwandan children decreased between 2005 and 2015 (from 51 to 38%) [15], growth stunting is still considered a major challenge to overall economic development in Rwanda, particularly among the poor children (49% stunted) and children living in rural areas (41% stunted) [15, 16]. To better understand the persisting challenges to reducing stunting in Rwanda, we used the 2014–2015 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data and conducted an assessment for 17 risk factors for stunting across all provinces in Rwanda, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) conceptual framework for childhood stunting [17, 18].

Methods

Data sources

We used the 2014–2015 Rwanda DHS open access dataset [19]. The DHS included a randomly selected national total of 12,793 households from five provinces. Of the 12,793 households, a sub-sample of 6350 (50%) households was randomly selected and data on child anthropometric measurements and development indicators were collected (N = 3594 children) [15]. A full protocol explaining the data collection process and sampling methods of DHS can be reviewed elsewhere [19].

Variables description

We have included a total of 17 variables related to three categories in the WHO stunting framework [17, 18]: i) Individual-level factors (sex, age group, parity, child’s weight at birth, history of diarrhea in two weeks prior to the survey); ii) Maternal (height, highest educational level, intake of parasite controlling drugs for mothers during pregnancy, number of days of daily intake of iron tablets or syrup by mothers during pregnancy, breastfeeding within the first hour after birth and household (household wealth index, household size, access to improved water at household, availability of improved toilet facility) factors and iii) Community level factors (household location data including province, sector and village; altitude (highland vs. lowland) and location (urban vs. rural).

Definitions

Stunting was measured by DHS, using the WHO Child Growth Standards and collected data on every child’s length/height, age and sex to calculate the number of standard deviations (Z-score) that his/her length/height is below or above the median of the 2006 WHO growth reference population [20]. These measures were recorded with two implied decimal places, thus we divided all values of DHS standard deviations by a hundred. Stunting was defined as a z-score lower than − 2. Mother’s height was considered low if it was < 145 cm [21]. Household wealth index was calculated using principal components analysis (PCA) of data on a household’s ownership of assets like television, radio, mobile telephone, computer and car, and housing characteristics (access to electricity, access to source of drinking water, type of floor material, type of toilet facility, number of bedrooms, and type of cooking fuel) [15]. Wealth index scores were adjusted for the type of residence (rural or urban). Then, DHS assigned each person in the population his/her household’s score. The study population was ranked according to their social economic scores and divided into five equal groups (20% of the population), known as wealth quintiles [22]. For this study, we re-grouped our sample of children into three groups: High-social economic status (SES) (highest two wealth quintiles), middle SES (middle wealth quintile) and low-SES (lowest two wealth quintiles) [15].

Child weight at birth was defined as low if it was less than 2.5 kg [23].

Location of the household was defined as highland if the household location is at an altitude of > 1642 m (median altitude of households), and lowland if the household location is at an altitude of < 1642 m.

Data analysis

To determine risk factors for stunting, we first conducted a full logistic regression model with all 17 variables by calculating odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. Then, we conducted a final logistic regression model by controlling for sex, province, and altitude. All variables with p-values 0.10 or less in the full model were considered in our final logistic regression model, and removed using backward stepwise selection stopping when all the final variables were significant at the α = 0.05 significance level. Stata/SE 13.1 was used for data analysis [24]. We used the svy commands to account for the complex survey sampling and used sampling weights to account for unequal probability sampling in different strata.

Results

Descriptive analysis

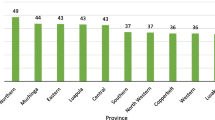

A total of 3594 children were included in this study (Table 1). Almost half of these children were females (49%; 1769/3594). At birth, only 5% (173/3329) of the children had low weight. Over half (58%; 2091/3594) of the children were 24–59 months of age, and 72% (2551/3565) had access to improved source of drinking water in the household. As for geographical location, 11% (406/3593) lived in the capital city of Kigali, 14% (500/3593) in the Northern Province and the rest were almost equally distributed among the three remaining provinces. Slightly less than half of them (48%; 1728/3594) lived in highlands, and 84% (3003/3594) in rural areas.

The prevalence of stunting was 38% (95% CI: 35.92, 39.52) in the sample. Over half of stunted children were males (57%; 774/1355; p < 0.01); 66% (894/1355) of them were aged 24–59 months (p < 0.01), and 55% (749/1355) lived in highland areas (p < 0.01). Most of children with stunting (79%; 1069/1355) were residents of the Western, Southern and Eastern provinces.

The median age of the mothers was 30 years (Interquartile range (IQR) 26–34), and most of them had at least primary school education (73%, 2615/3593). Over one-quarter of women (28%, 995/3593) had only one child at the time of the survey. When it comes to the history of antenatal medication intake, 45% (449/996) and 68% (531/781) of the mothers of stunted children took an anti-parasitic drug and at least 30 tablets of iron supplementation respectively, during pregnancy.

Risk factors for growth stunting

In the full logistic regression model, factors associated with growth stunting were: a) Individual characteristics, including higher risk among males (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.30–1.99, p < 0.01), children aged 6–23 months (OR 4.43, 95% CI 2.74–7.16, p < 0.01) and 24–59 months (OR 5.40, 95% CI 3.33–8.76, p < 0.01), low child weight at birth (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.24–3.23, p = 0.01); b) Maternal and household characteristics, including mothers’ height < 145 cm (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.56–5.08, p < 0.01), mother’s educational level of either only primary (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.03–2.15, p = 0.04) or never attended school (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.18–1.61, p = 0.01), household middle wealth index (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.00–1.85, p = 0.05) and poorest level (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.49–2.63, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

In the final logistic regression model, factors associated with growth stunting were: a) Individual characteristics, including higher risk among males (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.25–1.82, p < 0.01), children aged 6–23 months (OR 4.91, 95% CI 3.16–7.62, p < 0.01) and 24–59 months (OR 6.34, 95% CI 4.07–9.89, p < 0.01), low child weight at birth (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.39–3.23, p < 0.01); b) Maternal and household characteristics, including mothers’ height < 145 cm (OR 3.27, 95% CI 1.89–5.64, p < 0.01), mother’s educational level of either only primary (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.25–2.34) or never attended school (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.37–2.92, p < 0.01), history of not taking anti-parasite drugs during pregnancy (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09–1.53, p < 0.01), household wealth index middle (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.12–1.86) and poorest level (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.45–2.29, p < 0.01); and c) Community level characteristics including living in highlands (OR 1.29, 0.99–1.67, p = 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we used nationally representative population-based survey data of Rwanda that included nearly 3600 children aged less than 5 years. The prevalence of stunting has decreased from 51% in 2005 to 38% in 2015 in Rwanda [15]. However, approximately two in every five children are stunted, which indicates that this remains a serious public health challenge.

Boys were at a higher risk for stunting than girls, which is consistent with other studies reporting similar trends from sub-Saharan Africa [25,26,27]. This might be due to preferences in feeding practices or other types of exposures [25]. The nutritional status might be explained by “biological fragility” because boys are expected to grow at a slightly more rapid rate compared to girls and their growth is perhaps more easily affected by nutritional deficiencies or other disease or exposures [28].

We indicated that increasing age of the child had a significant association with stunting. Children aged 6–23 months were at lower risk of stunting than those in the older age group 24–59 months, which has been reported by other studies [22, 29]. Rates of exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months are high in Rwanda (87%), which may provide a protective effect against stunting at early ages [15]. The gradual increase of stunting among children under-5 years in Rwanda might be due to the inappropriate food supplementation during the weaning period when infants should undergo a transition from exclusive breastfeeding to including complementary foods in their diet [30, 31]. Mothers receive education regarding breastfeeding and transition to complementary feeding through the Community Based Nutrition Program (CBNP) at the village level [32], but this is a self-selecting group who choose to attend these educational sessions, and therefore may miss mothers of children who are malnourished or at-risk for developing malnutrition. Additionally, mothers may prolong the duration of breastfeeding, which is known to be a risk factor for stunting [22, 33, 34], especially if they do not know when to commence giving complementary food or due to poverty-related barriers to adequate complementary feeding. According to studies from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Peru and Nepal, educated mothers, coming from wealthy households, tend to be more aware of the nutritional needs of their children [30, 35,36,37,38]. Also, the reverse association between household wealth and stunting has been observed in several studies [37,38,39,40,41]. The wealth of households is a proxy for the purchasing power for food and other nutritional goods needed for the health of the children. Therefore, children in low-socioeconomic status households are less likely to be exposed to good nutrition, which will lead to stunting. However, the recent evidence on a slow economic growth and smaller reduction in stunting as a response to the gross national income (GNI) growth in SSA countries has resulted in an increased international focus on scaling-up maternal and child nutrition-specific interventions [42], as nearly the only way to accelerate stunting reduction, and it is worrying that this would undermine the role of poverty in persisting high rates of stunting and its slow reduction in SSA [43]. Overall, rates of stunting in Rwanda (38%) are similar to rates of poverty (39%) [44]; while poverty is reducing overtime from 45% in 2010, and stunting from 44% in 2010 [45], the association between poverty and stunting in our study indicates that further investments in social protection programs that specifically target households with young children, or women of reproductive age, may be further needed in Rwanda to address the high burden of stunting. Rwanda has adopted pro-poor policies to advance the economic development of the country with an equity approach. As a predominantly rural agrarian society, with high population density, efforts to strengthen the agricultural sector are key to reducing food insecurity and advancing economic development as well as investments in human capital starting with promotion of optimal early childhood development [46]. Specific efforts in Rwanda’s social protection system have targeted precisely this group by focusing on cash for work programs that are more gender and child-sensitive, to ensure women who are pregnant and breastfeeding are not unintentionally excluded from the program [47]. The trend of poverty and stunting reducing at similar rates, provides promise that poverty-reduction initiatives are achieving this goal however the ambitious target to reduce stunting at quicker rates may require further government investment to accelerate poverty reduction, which is stagnating according to the latest measure of poverty at 38% in 2017 [48], and strategic interventions targeting specific risk factors for stunting including households at high altitude, low birth weight births, and appropriate feeding across the early years of life.

These study findings will further contribute to evidence to nutritionists and public health researchers to reshape and design new interventions to reduce the prevalence of stunting in Rwanda, starting with upstream prenatal and maternal factors. Our study showed that children born with a low weight (< 2.5 kg) were more likely to be stunted, in comparison to children with weight ≥ 2.5 kg at birth. This finding is aligned with reports from Pakistan, Mexico, and Nepal [22, 49, 50]. Additionally, we found mother’s height has an association with stunting, which is aligned with the findings of the COHORTS group study in Brazil, Guatemala, India, the Philippines and South Africa [51]. These two predictors are related to maternal factors that require an additional understanding of nutrition and health during pregnancy and addressing intergenerational cycles of malnutrition [52]. These maternal factors require investments by the health sector, to improve the nutrition of women of reproductive age and invest in strategies to prevent low birth weight births, such as improved spacing and quality antenatal care and these priorities are part of the latest government of Rwanda strategies in the health sector [53].

A history of use of deworming drugs during pregnancy was associated with a decreased risk of stunting. This association could be a result of reduced helminths infections during pregnancy and promote better absorption of nutrients by the mother. However, interestingly, there was no statistically significant association between stunting and the availability of improved sanitation and water at the household, which are considered by most of the interventions to improve hygiene and prevent the spread of disease and helminths/parasites. Our findings conflict with other studies on stunting and hygiene. Hien and Hoa found access to clean water and the availability of a hygienic toilet as intermediate risk factors for stunting [54], which might indicate a weak association [29]. However, Danei et.al. found that lack of an improved toilet is a major risk factor for stunting in an international meta-analysis on 137 countries in resource-limited settings [6].

Another risk factor for child growth stunting was among children living in households located in high-altitudes. Rwanda is known by the name of “Land of 1,000 Hills” due to its geographical landscape. Villages can exist on the top of these hills in high-altitudes. While we were surprised that our analysis did not show that living in a rural area is a risk factor, this may be due to the fact that many of these rural populations are also high altitude, which was significant. Living in rural high-altitudes has been associated with higher rates of child stunting in Peru [55]. This might be related to environmental and climate factors, differences in diet due to food availability in highlands versus lowlands, and increased level of physical activity for children living in highlands [55]. This finding warrants further investigation into the association between stunting and living in high-altitudes in Rwanda. Community-based interventions for stunting specifically targeted to rural, high-altitude areas may be one strategy for targeting this high-risk group, especially when it comes to complementary feeding, childhood illnesses preventive interventions, and mothers’ education.

Study limitations

This study was based on the DHS survey which lacked other additional information that we could have included in the analysis as per the WHO Framework for predictors of stunting [17, 18], such as i) Poor hygiene practices, ii) Contamination of water, and iii) Quality of food intake. In addition, most of children’s data in DHS are self-reported by primary caregivers which is subject to a hidden recall bias, however, the DHS sampling method, and the methods of adjustment for the sampling and weighting suggest a good strengths for this study [56].

Conclusion

Stunting prevalence is high in Rwanda, with rates seen to increase with an increasing age starting among infants on complementary feeding (> 6 months) and into early childhood. Our study findings suggest that stunting could be reduced if integrated interventions are implemented to improve child and family-level factors that contribute to stunting. Efforts to reduce poverty, improve maternal nutrition for preventing low birth weight babies, increase access to quality and timely antenatal care services and strengthen community-based nutrition activities to promote exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months and continued breastfeeding up to 24 months with the addition of high quality complementary feeding, would accelerate stunting reduction.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- Kg:

-

Kilograms

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCA:

-

Principal components analysis

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The State Of The World’s Children 2016. New York: A fair chance for every child; 2016.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017. In: Building resilience for peace and food security. Rome: FAO; 2017.

World Health Organization (WHO). Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry - Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva; 1995.

Pradhan M, Sahn D, Younger S. Decomposing world health inequality. J Health Economics. 2003;22:271–93.

Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):60–70.

Danaei G, Andrews KG, Sudfeld CR, Fink G, McCoy DC, Peet E, et al. Risk Factors for Childhood Stunting in 137 Developing Countries: A Comparative Risk Assessment Analysis at Global, Regional, and Country Levels. PLoS Med. 2016;13(11):e1002164.

Martorell R, Khan LK, Schroeder DG. Reversibility of stunting: epidemiological findings in children from developing countries. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48(Suppl 1):S45–57.

Black MM, Walker SP, LCH F, Andersen CT, AM DG, Lu C, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389:77–90.

Fink G, Peet E, Danaei G, Andrews K, McCoy DC, Sudfeld CR, et al. Schooling and wage income losses due to early-childhood growth faltering in developing countries: national, regional, and global estimates. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(1):104–12.

Walker SP, Chang SM, Powell CA, Grantham-McGregor SM. Effects of early childhood psychosocial stimulation and nutritional supplementation on cognition and education in growth-stunted Jamaican children: prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1804–7.

Ministry of Health. The Cost of Hunger in Rwanda: Social and Economic Impacts of Child Undernutrition in Rwanda-Implication on National Development and Vision 2020. Kigali, Rwanda; 2014. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/wfp263106.pdf.

Niyonzima S, Hedt-Gauthier B, Condo JU, Ngabo F, Munyanshongore C. District plan to eliminate malnutrition 2010–2013: a comprehensive tool to address malnutrition among under five children in Rwanda. Kigali: Case of Kirehe District; 2010.

Ministry of Local Government, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources. Rwanda National Food and Nutrition Policy 2013-2018. Kigali: 2014. http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/rwa151338.pdf.

Ministry of Health. Health Sector Policy. Kigali: 2015. http://www.moh.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/policies/Health_Sector_Policy___19th_January_2015.pdf.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014–15. Rockville, Maryland, USA: NISR, MOH and ICF International; 2015.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda & World Food Programme. Rwanda 2015. Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis. Kigali: 2016. http://www.statistics.gov.rw/publication/comprehensive-food-security-and-vulnerability-analysis-cfsva-report-2015.

Stewart CP, Iannotti LG, Dewey KF, Michaelsen KW, Onyango A. Contextualising complementary feeding in a broader framework for stunting prevention. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(Suppl 2):27–45.

Wirth JP, Rohner F, Petry N, Onyango AW, Matji J, Bailes A, et al. Assessment of the WHO Stunting Framework using Ethiopia as a case study. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12310.

United States Agency for International Development. Demographic and health surveys, data [Internet]. [cited 2002 Jul 20]. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/data.

World Health Organization (WHO). Child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

Mavalankar DV, Trivedi CC, Gray RH. Maternal weight, height and risk of poor pregnancy outcome in Ahmedabad, India. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31(10):1205–12.

Tiwari R, Ausman LM, Agho KE. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives: evidence from the 2011 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):239.

World Health Organization. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013.

Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Boys are more stunted than girls in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7(1):17.

García Cruz LM, González Azpeitia G, Reyes Súarez D, Santana Rodríguez A, Loro Ferrer JF, Serra-Majem L. Factors associated with stunting among children aged 0 to 59 months from the central region of Mozambique. Nutrients. 2017;9(491):1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050491.

Bukusuba J, Kaaya A, Atukwase A. Predictors of Stunting in Children Aged 6 to 59 Months: A Case-Control Study in Southwest Uganda. Food Nutr Bull. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572117731666.

Condo JU, Gage A, Mock N, Rice J, Greiner T. Sex differences in nutritional status of HIV-exposed children in Rwanda: a longitudinal study. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(1):17–23.

Kismul H, Acharya P, Mapatano MA, Hatløy A. Determinants of childhood stunting in the Democratic Republic of Congo: further analysis of demographic and health survey 2013–14. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):74.

JSAS NF. Effect of weaning period on nutritional status of children. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16(8):529–31.

Goudet SM, Griffiths PL, Bogin BA, Madise NJ. Nutritional interventions for preventing stunting in children (0 to 5 years) living in urban slums. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011695.

Ministry of Health. National Community Based Nutrition Protocol (NCBNP). Kigali; 2010. http://data.over-blog-kiwi.com/0/71/40/80/201308/ob_95077572a66adc2f6a4ea93c06e66d58_protocol-cbn.pdf.

Caulfield LE, Bentley ME, Ahmed S. Is prolonged breastfeeding associated with malnutrition?: evidence from nineteen demographic and health surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:693–703.

Marquis GS, Habicht J-P, Lanata CF, Black RE, Rasmussen KM. Association of Breastfeeding and Stunting in Peruvian toddlers: an example of reverse causality. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:349–56.

Urke HB, Bull T, Mittelmark MB. Socioeconomic status and chronic child malnutrition: wealth and maternal education matter more in the Peruvian Andes than nationally. Nutr Res. 2011;31(10):741–7.

Khanal V, Sauer K, Zhao Y, Black R, Cousens S, Johnson H, et al. Determinants of complementary feeding practices among Nepalese children aged 6–23 months: findings from demographic and health survey 2011. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):131.

Ikeda N, Irie Y, Shibuya K. Determinants of reduced child stunting in Cambodia: analysis of pooled data from three demographic and health surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(5):341–9.

Delpeuch F, Traissac P, Martin-Prével Y, Massamba J, Maire B. Economic crisis and malnutrition: socioeconomic determinants of anthropometric status of preschool children and their mothers in an African urban area. Public Health Nutr. 2000;3(1):39–47.

Hong R, Mishra V. Effect of wealth inequality on chronic under-nutrition in Cambodian children. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(1):89–99.

Mostafa Kamal SM. Socio-economic determinants of severe and moderate stunting among under-five children of rural Bangladesh. Malays J Nutr. 2011;17(1):105–18.

Rahman A, Chowdhury S. Determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children in Bangladesh. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(02):161.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;382(9890):452–77.

World Bank Group. Stunting Reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, D.C., USA: The World Bank Group; 2017. p. 14–9.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR). Rwandan Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey - 2013/14, Main Indicators Report. Kigali: 2015. http://www.statistics.gov.rw/publication/main-indicators-report-results-eicv-4.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Calverton, Maryland, USA: NISR, MOH and ICF International; 2012.

Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. The government of Rwanda poverty reduction strategy paper. Kigali, Rwanda: Republic of Rwanda; 2002.

Republic of Rwanda. Vision 2020 Umurenge Programme (VUP): Accelerating sustainable graduation from extreme poverty and fostering inclusive national development-Expanded Public Works Guidelines. Kigali: Local Administrative Entities Development Agency (LODA); 2017. https://loda.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/2014_PRO/Documents/ePW_GUIDELINES_2017_ENGLISH_VERSION.pdf.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR). Rwanda Poverty Profile Report. Kigali. Rwanda: Republic of Rwanda; 2016/17. p. 2018.

Saleemi MA, Ashraf RN, Mellander L, Zaman S. Determinants of stunting at 6, 12, 24 and 60 months and postnatal linear growth in Pakistani children. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 2001;90(11):1304–8.

Varela-Silva MI, Azcorra H, Dickinson F, Bogin B, Frisancho AR. Influence of maternal stature, pregnancy age, and infant birth weight on growth during childhood in Yucatan, Mexico: a test of the intergenerational effects hypothesis. Ame J Human Biol. 2009;21(5):657–63.

Addo OY, Stein AD, Fall CH, Gigante DP, Guntupalli AM, Horta BL, et al. Maternal height and child growth patterns. J Pediatr. 2013;163(2):549–54.

Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Davey Smith G, John NA. Association of maternal height with child mortality, anthropometric failure, and anemia in India. JAMA. 2009;301(16):1691–701.

Ministry of Health. Fourth Health Sector Strategic Plan: July 2018 - June 2024. Kigali: 2018. http://moh.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/Docs/FINALH_2-1.pdf.

Hien NN, Hoa NN. Nutritional status and determinants of malnutrition in children under three years of age in Nghean, Vietnam. Pakistan J Nutrition. 2009;8(7):958–64.

Pomeroy E, Stock JT, Stanojevic S, Miranda JJ, Cole TJ, Wells JCK. Stunting, adiposity, and the individual-level “dual burden” among urban lowland and rural highland peruvian children. Am J Hum Biol. 2014;26(4):481–90.

Corsi JD, Neuman M, Finlay EJ, Subramanian S. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1602–13.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Funding

BHG received funding from the Harvard Medical School Global Health Research Core to support this work. ZEK is supported by the Harvard Medical School Global Health Equity Research Fellowship, funded by Jonathan M. Goldstein and Kaia Miller Goldstein. None of the funders had made any role in the design of the study, data collection, and analysis, interpretation of data and in the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the DHS program repository, including the protocol for the data collection [19]. https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Rwanda_Standard-DHS_2015.cfm?flag=0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AN, BHG, FK and ZEK conceived the study. AN and ZEK conducted the data analysis and coordinated the overall activity. BHG, CM, CMK, KB and FK participated in the design of the study. BHG, CM and CMK reviewed the statistical analysis. AN, BHG, CM, CMK, KB, JM, AN, FK and ZEK interpreted the data. AN and ZEK developed the first draft of the manuscript. AN, BHG, CM, CMK, KB, JM, AN, FK and ZEK reviewed the first draft and drafted subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the text and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We have conducted analysis for a publicly available data, no ethics was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ZEK is a member of the editorial board of BMC Public Health (associate editor). The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nshimyiryo, A., Hedt-Gauthier, B., Mutaganzwa, C. et al. Risk factors for stunting among children under five years: a cross-sectional population-based study in Rwanda using the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Public Health 19, 175 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6504-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6504-z