Abstract

Background

Despite substantial improvements in accessibility of Anti-Retroviral Treatment (ART), death of children on ART remains a prevailing challenge in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. However, the pooled magnitude of mortality at different ART follow-up periods remains unknown for the region. We estimated the pooled proportion of all-cause mortality for pediatric patients receiving first-line ART at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months follow-up period in SSA.

Methods

We searched for relevant articles published between January 2014 and June 2018 on PubMed, Hinari and Google scholar databases. We searched for additional articles from reference lists and 2014–2018 abstracts archived by the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) and the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS).

Results

We reviewed 29 articles reporting mortality among pediatric ART patients at different follow-up periods in countries from 2001 to 2016. Among the 51,619 pediatric ART patients in these cohorts, studies reported 4061 (7.9%) all-cause cumulative death. The cumulative pooled proportion of mortality at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months of ART were 3% (95% CI: 3.0–4.0), 5% (95% CI: 4.0–6.0), 6% (95% CI: 5.0–7.0) and 7% (95% CI: 6.0–8.0), respectively.

Conclusions

In SSA, significant proportion of mortality among children occurs in the first 3–6 months of ART initiation. Western Africa has a little higher estimate of mortality among pediatric ART patients at 6 and 12 months of follow-up. Strategies to prevent early mortality including thorough screening and management of opportunistic infections before ART initiation are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There have been several significant developments in the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) field since 2013. Evidence revealed that early ART initiation among children results in reduced HIV-associated morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. In line with this evidence the World Health Organization (WHO) revised its recommendation in 2013 to initiate ART for all < 5 years pediatric HIV-infected patients regardless of CD4 cell count or WHO clinical stage [3]. Based on review of additional new evidence [4, 5], this recommendation was expanded in 2016 to “test and treat” all PLHIV [6]. These progressive recommendations were geared towards achieving the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90:90:90 ambitious goal of controlling the Acquired Immune Deficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic by 2020 where 90% of all PLHIV will know their HIV status, 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive ART, and 90% of all people receiving ART will have viral suppression [7].

Despite substantial improvements in accessibility of ART and improved program implementation, death and loss to follow-up (LTFU) have been a prevailing challenge among PLHIV of all ages. However, attrition is much more pronounced in pediatric cases. There have been various studies conducted in SSA countries to determine the rate of mortality among pediatric ART patients. A systematic review conducted by Fox et al., estimated attrition (death and LTFU) of pediatric ART patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) based on studies from 2008 to 2013 [8]. However, the pooled magnitude of mortality at different ART follow-up periods have not been separately analyzed and reported. The aim of this review is to determine the pooled magnitude of mortality at different follow-up period among pediatric patients who are on first-line ART in SSA countries based on studies published since 2014. This timeframe was selected to include new studies that were not covered in the systematic review conducted in LMICs [8]. The lessons from such studies can guide pediatric HIV program implementation in SSA and help policy makers and program managers to make informed decisions to prevent deaths among pediatric ART patients.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for this review [9]. We searched PubMed, Hinari and Google scholar databases for peer-reviewed articles published from January 1, 2014 to June 24, 2018. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text search terms used for the search included “mortality”, “death”, “survival”, “retention”, “attrition”, “outcome”, “antiretroviral”, “HIV treatment”, “pediatric”, “paediatric”, “child”, “children”, and “Africa”. We searched conference abstracts from CROI archives using “mortality” and IAS using “mortality” or “survival” from 2014 to 2018. See our exact search strategy used for different databases on Additional file 1. Furthermore, the data source was supplemented by hand searching through reference lists of included studies identified through the search. We limited the search to human subject studies and articles published in English. The review protocol was registered at the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018099618), registration number CRD42018099618).

Study selection

We included observational studies conducted in SSA countries using cohort (prospective or retrospective) study design to determine mortality. We excluded articles that used clinical trial, case-control, cross-sectional, case reports, case series, reviews, qualitative studies, editorials, commentaries, and letters to editors to avoid some level of methodological heterogeneity. We included studies examining HIV-infected children < 18 years old who received standard first-line ART at any type or level of health facility that followed prevailing national treatment guidelines. Studies addressing both adults and children were included when data provided for children were reported separately.

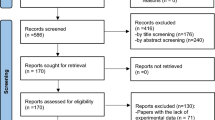

SL supervised the primary search conducted by IA. We obtained full-text copies of all potentially relevant articles after the initial title and abstract screening for further assessment by the two authors based on the eligibility criteria. Full-text articles were reviewed by IA and SL, and any differences were resolved through consensus of both authors. Full-text articles were requested from the authors when they were not available. Articles that were not be eligible at this stage were excluded; and reasons for exclusion were documented (see Fig. 1). Literature obtained using the search strategy were uploaded to Zotero software that helps in collecting, organizing and managing articles.

Data abstraction

For studies that met the inclusion criteria, relevant data were extracted by the first reviewer (IA) using a predefined Excel tool developed for the review. All extracted data were checked by the second reviewer (SL) to ensure the quality of data abstraction. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. Relevant variables extracted from studies include name of first author, year of publication, country/setting, year(s) of data collection, sample size, number of facilities, duration of follow-up, sociodemographic characteristics of population (mean or median age, and sex), number of deaths and LTFU at different time period, and incidence of mortality. Where there was missing data or uncertainty about the data, efforts were made to contact study authors for raw data and/or provide clarification.

Outcomes

The proportion of children who died while taking ART at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months of follow-up period was the primary outcome.

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of each of the included studies using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies provided by the U.S Department of Health and Human Services [10]. The tool has 14 questions or criteria on (1) research question; (2 & 3) study population; (4) groups recruited from the same population and uniform eligibility criteria; (5) sample size justification; (6) exposure assessed prior to outcome measurement; (7) sufficient timeframe to see an effect; (8) different levels of the exposure of interest; (9) exposure measures and assessment; (10) repeated exposure assessment; (11) outcome measures; (12) blinding of outcome assessors; (13) follow-up rate; and (14) statistical analyses. Two authors (IA and SL) independently assessed the studies and any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The final assessment score is given as “good” or “fair” or “poor”.

Data analysis

We undertook an initial descriptive analysis of all included studies that have reported aggregate all-cause mortality among children enrolled in ART. Meta-analysis was performed to estimate the pooled mortality and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for cohorts that reported number of children died at different follow-up periods. We interpolated or extrapolated data for any missing time period when possible for a few (n = 4) of the studies [11,12,13,14]. For example, if a cohort reported 6- and 24-months mortality, we interpolated 12 months mortality assuming a linear increase between two points. Heterogeneity between studies was examined using the I2 statistic and the p-value for heterogeneity [15]. I2 ≥ 75% or P < 0.1 was considered as high statistical heterogeneity [16]. We plotted each mortality estimate and its 95% CI using forest plots and combined estimates using a random-effects model after stabilizing the variance by transforming the proportions using the Freeman-Tukey double-arcsine method because of evidence of high heterogeneity between studies [17].

Sub-group analysis of pooled mortality at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months was conducted. Countries were divided geographically into three groups as Eastern, Western and Southern Africa. We have excluded multinational studies that reported combined results of Southern and Eastern African countries. Accordingly, a study conducted by Ben-Farhat et al. [11] was excluded from the 3, 6 and 24 months pooled mortality analysis. Similarly, both Ben-Farhat et al. [11] and Lamb et al. [18] were excluded from the 12 months pooled mortality analysis. All meta-analysis results were summarized graphically using Forest plots. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.

Sensitivity analysis

To determine the proportion of the summary results driven by some studies, we conducted three different sensitivity analysis by excluding studies with the largest sample size [19, 20], studies with high rate of LTFU (> 15%) [20,21,22,23], and studies with missing data (without interpolation or extrapolation) [11,12,13,14].

Publication bias

We used “metabias” that performs the Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test and the Egger et al. regression asymmetry test for publication bias when ten or more studies reported mortality at different time periods. Failure of this confidence interval to include zero or p-value < 0.1 indicates asymmetry in the funnel plot and may give evidence of publication bias [24,25,26].

Results

Our search strategy returned a total of 2194 articles, and 1477 remained after de-duplication. Of the 1477 articles, 41 studies were eligible for full-text review. Four additional studies were hand searched and included for full-text review. After screening full-text of 45 studies with our inclusion criteria, an additional 16 studies were excluded because of various reasons indicated in Fig. 1. In total, 29 cohort studies (journal articles) were selected for inclusion in the review. Searching for grey literature using conference abstracts archives resulted in one eligible abstract which was rejected later due to inaccessible full-text for final review. Of 22 study authors contacted for raw data/or provide clarification, 50% responded to our request. All of the included studies, except three [27,28,29] were rated as “good” for the methodological quality assessment. See Additional file 2 for detailed quality assessment results of all studies.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of studies included in the review are summarized in Table 1. The studies were published between 2014 and 2018, but studied all-cause mortality among cohorts of children enrolled on ART from 2001 to 2016 in 15 SSA countries. One third (n = 5, 33%) of the countries had four or more studies. The highest number of publications were from Ethiopia (n = 9) followed by Malawi (n = 5) and South Africa (n = 5). There were five multi-national studies [11, 18, 19, 21, 30]. The total sample size of the combined studies was 51,619, with each cohort ranging from 93 to 10,875 children. About 90% (n = 26) of the studies reported deaths among children 15 years of age or younger [11,12,13, 18,19,20,21,22, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Nineteen studies reported median or mean age of children which is ranged from 0.5 to 9 years [11,12,13,14, 21, 22, 27, 29, 30, 32,33,34,35,36, 41,42,43,44,45].

Magnitude of mortality

A total of 4061 all-cause cumulative deaths were reported by the 29 included studies that had various cohort follow-up time periods. The highest proportion of deaths was reported by a study in South Africa (21.0%, n = 143) [43]; and the lowest was from one of an Ethiopian cohort (2.0%, n = 6) [35]. Among 14 studies that reported on follow-up time of children on ART, the median or mean follow-up time ranged from 11 to 68 months for multi-country cohort in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Malawi and Zambia [21] and Ethiopia [40], respectively. Incidence of mortality was reported by 13 studies and ranged from 0.98 to 6.9 per 100-child year in Mozambique [33] and among a multi-country cohort from Mozambique, Malawi and Guinea [30], respectively.

Among studies that reported on mortality along with the patients’ follow-up period, proportion of mortality at 3 months of ART ranged between 1.1 and 7.8% in cohorts from Tanzania [41] and Mozambique [27], respectively. Proportion of mortality at 6 months ranged between 1.6% in cohorts from Ethiopia [35] and 12.4% in cohorts from South Africa [28]. The South African study focused on younger children < 2 years of age. Proportion of mortality at 12 months ranged between 2.0% in cohorts from Ethiopia [35] and 16.1% in cohorts from Mozambique [27]. Similarly, at 24 months of ART, proportion of mortality ranged from 3.8% among cohorts in Nigeria [23] to 20.2% among cohorts from Mozambique [27]. Table 2 shows proportion of deaths at each reported time period by country.

Meta-analysis of mortality

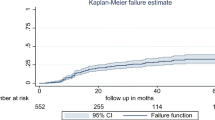

Meta-analysis of pooled estimates of mortality were conducted for studies that have reported on proportion of children who died at different follow-up periods. We excluded studies with poor methodological quality [27,28,29]. Accordingly, a total of 8 [11, 23, 34, 37, 38, 40, 41, 45], 14 [11,12,13,14, 20, 21, 23, 32, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 44], 17 [11,12,13,14, 18,19,20,21,22,23, 32, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 44] and 10 [11,12,13,14, 20, 23, 37, 38, 40, 44] studies were included in the meta-analysis to estimate pooled mortality at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months of follow-up period, respectively. The overall random-effects cumulative pooled proportion of mortality at 3, 6, 12 and 24 month of ART initiation were 3.0% (95% CI: 2.0–5.0), 5.0% (95% CI: 3.0–6.0), 6.0% (95% CI: 5.0–7.0) and 6.0% (95% CI: 5.0–8.0), respectively. The between-study heterogeneity was significant (p-value < 0.0001), with I2 value of 88.11% for 3 months, 93.99% for 6 months, 95.32% for 12 months, and 88.44% for 24 months.

Sub-group analysis

Sub-regional analysis of pooled mortality at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months indicated that, the pooled proportion of mortality at 3 months of ART initiation were 4.0% (95% CI: 4.0–5.0) in Western and 3.0% (95% CI: 2.0–4.0) in Eastern Africa regions. The 6 months pooled estimate were 5.0% (95% CI: 3.0–8.0) in Western and 4.0% (95% CI: 3.0–5.0) in Eastern Africa regions. The 12 months pooled estimate were 6.0% (95% CI: 3.0–10.0) in Western, 5.0% (95% CI: 4.0–7.0) in Eastern, and 8.0% (95% CI: 5.0–11.0) in Southern Africa regions. Similarly, the 24 months pooled estimate were 5.0% (95% CI: 3.0–7.0) in Western and 7.0% (95% CI: 5.0–9.0) in Eastern Africa regions. In all the meta-analyses, the between-study heterogeneity was significant (> 75%) with p-value of < 0.001 except for few studies reported from West African at 3 and 24 months.

Sensitivity analysis

To determine what proportion of the summary results were driven by studies with the largest study population, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding Melaku et al. [20] for the 6, 12 and 24 months estimate and both Melaku et al. [20] and Davies et al. [19] for the 12 month estimate (more than 40% of all the meta-analysis study participants). Following removal of these studies, the overall pooled estimate at 24 months increased by 1% (7.0% (95% CI: 5.0–8.0)).

In order to examine the impact of extrapolated or interpolated data, we conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding Ben-Farhat et al. [11] and Ebissa et al. [12] for 12 months estimate and Ebonyi et al. [13] and Njom et al. [14] for the 24 months estimate which had missing data. Following removal of these studies, the overall pooled estimate was not changed for the different follow-up periods indicating that our results were not driven by studies with extrapolated/interpolated data.

In addition, to determine the effect of studies with high rate of LTFU (> 15%), we conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding Auld et al. [34] and Ojikutu et al. [23] for 3 months estimate; Melaku et al. [20], Ojikutu et al. [23], and Porter et al. [21] for 6 months estimate; Brophy et al. [22], Melaku et al. [20], Ojikutu et al. [23], and Porter et al. [21] for 12 months estimate; and Melaku et al. [20] and Ojikutu et al. [23] for 24 months estimate. Following removal of these studies, the pooled estimate was not changed except for the 24 months estimate (7.0% (95% CI: 6.0–8.0)) which increased by 1%, compared with the original finding. However, excluding these studies has lowered the heterogeneity between-studies. We reported this result as the pooled estimates of mortality among pediatric patients on HIV treatment in SSA. Figure 2a and b illustrate mortality rates at 3 and 6 months and Fig. 3a and b illustrate mortality rates at 12 and 24 months of ART initiation with 95% CI and I2 using forest plots.

Considering the above effect of LTFU on heterogeneity of studies, we conducted sub-regional analysis by omitting studies with high rate of LTFU [20,21,22,23]. After excluding these studies, the pooled estimate was not changed except for 6 months (6.0% (95% CI: 3.0–10.0)) and 12 months (7.0% (95% CI: 3.0–13.0)) estimates in Western Africa region which increased by 1%, compared with the original findings. However, excluding these studies has lowered the between-study heterogeneity. We did not report pooled mortality at 3 month of ART initiation by sub-regions due to limited number of studies to compare. Similarly, there were no eligible studies from Southern Africa for this sub-regional analysis except a single report at 12 months follow-up time [19]. We reported this result as the sub-regional pooled estimates of mortality among pediatric patients on HIV treatment in SSA. Figures 4, 5 and 6 illustrate mortality rates by sub-regions at 6, 12 and 24 months of ART initiation with 95% CI and I2 using forest plots, respectively.

Publication bias

The funnel plot and nonsignificant Egger’s test was conducted for all eligible studies included in the original meta-analysis. The test for 14 studies reported 6 months data (P > 0.402), 17 studies reported 12 months data (P > 0.702), and 10 studies reported 24 months data (P > 0.191) show no evidence of asymmetry suggesting no publication bias. There was graphical symmetry of funnel plots (see Additional file 3).

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality of HIV-infected children started on first-line ART at different follow-up time periods in SSA countries. The cohort size for this review included 51,619 pediatric patients on first-line ART in 15 SSA countries reported by studies published between 2014 and 2018. The cumulative pooled estimate of this study suggests that ART programs in SSA have been losing 3.0, 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0% of HIV-infected children due to death at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after ART initiation, respectively. Nevertheless, these cumulative proportion of death at different time periods were not consistently reported by all the studies. We identified that nine studies reported mortality at 3 months, seventeen studies reported mortality at 6 months, 16 studies reported mortality at 12 months, and ten studies reported mortality at 24 months of ART follow-up.

The review showed some degree of variability on attrition of pediatric cohorts enrolled in ART due to death. The overall proportion of death among pediatric patients enrolled on ART across all cohorts ranged between 2.0% from Ethiopia [35] and 21.0% from South Africa [43]. A systematic review conducted in LMICs reported a higher proportion of mortality, ranging between 0.0% from Botswana and 26.0% from Mozambique [8]. This difference could be due to a variation in ART enrollment periods where the previous studies addressed children who started ART in earlier years (before 2012) with different treatment eligibility criteria. Since 2013, the WHO has made significant changes in the recommended pediatric age for ART initiation, regardless of clinical or immunologic status [3, 6, 46] based on evidence that supported early initiation of ART to decrease childhood HIV-associated morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. However, there was variation among SSA countries in terms of time to adopt and implement new recommendations [47].

There are very few similar reviews against which we can compare our findings of pooled mortality estimates at different time period after ART initiation among pediatric patients. A pooled analysis of individual data from 16 clinics in SSA countries provided estimates of mortality at 6, 12 and 24 months of ART follow-up in pediatric cohorts enrolled until 2007 [48]. Our review reported the same results for all the indicated follow-up periods that reaffirm the previous findings. On the other hand, a systematic review without pooled estimate of mortality conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of pediatric ART in resource-limited settings reported 12 months proportion of mortality ranging from 0.0–18.8% [49] among patient cohorts of 2008 or earlier. A similar review conducted in Africa to describe retention of HIV-infected children in the first year of ART indicated that reported mortality ranging from 3 to 15% among studies published between 2006 and 2013 [50]. These findings were somewhat similar with our report at 12 months post-ART where the mortality was estimated to be between 2.0 and 16.1%.

Sub-regional analysis of pooled estimates of mortality conducted to minimize heterogeneity of studies indicated a little higher estimate in Western Africa compared with Eastern Africa at 6 and 12 months of ART follow-up. This could be due to a difference in study settings and cohort years. For instance, the Eastern African studies included recent cohorts up to 2016 who have benefited from early initiation of ART due to a change in the WHO’s recommendation to start ART for all children under 5 years of age since 2013 [3]. On the other hand, the pooled estimates of mortality in this review showed higher deaths among children within the first 6 months of ART initiation. This finding is in congruent with a systematic review conducted in Africa to estimate the effectiveness of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and ART in HIV-infected children which reported higher (more than half) number of the deaths during the first 6 months of ART initiation [51]. This could be due to undiagnosed Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS) which is a common complication in patients starting ART specially among patients with advanced disease stage and low CD4 cell count in African cohorts [52]. Studies conducted in South Africa revealed that 21% of children initiating ART developed IRIS [53]; and that IRIS accounted for one quarter of deaths in the first 6 months [54]. A systematic review conducted in low- and high-income countries reported a higher incidence of IRIS following ART initiation [55].

Our review has some limitations. Firstly, similar to a previous systematic review of retention of pediatric patients in LMICs [8], our review included only documented mortality. Most of the studies indicated that their reported mortality could be underestimated in the absence of a mechanism to ascertain the outcomes among children reported as LTFU. In this review, reported LTFU ranged from 2.5% [19] to 31.9% [27] that could underestimate pooled mortality. It is important for future studies to ascertain outcomes of LTFU pediatric ART patients to estimate the true proportion of deaths in this population. Secondly, our review identified a need for additional information on number of deaths at different follow-up time points. In order to fill the gap, we contacted 22 authors through email but only half provided additional information as requested. Thus, we excluded seven studies that did not report mortality at any of the follow-up times from the pooled estimates; and interpolated or extrapolated missing values for four studies. Thirdly, in our review, since few studies reported on mortality beyond 24 months of ART follow-up, we could not estimate the long-term pooled proportion of children who died while on ART. Fourthly, the review was limited to English language studies and we could have missed studies that were published in other languages. Finally, our review revealed significant heterogeneity among studies. This could be partly explained by a difference in age categories of pediatric patients studied, duration of ART follow-up periods, and ART eligibility criteria due to a change in the WHO’s recommendation among the studies. In addition, during sensitivity analysis, we found that studies with high rate of LTFU (> 15%) have contributed to the significant heterogeneity between-studies. In this review, we reported pooled estimates by excluding these studies to minimize the heterogeneity. The result from excluding these studies did not have much effect on the pooled estimates but significantly reduced the heterogeneity between-studies, compared with the original estimates. Furthermore, we conducted sub-regional analysis of pooled estimates along their geographical setting to further minimize the heterogeneity. Despite this heterogeneity, we believed that pooling the estimates of mortality at different follow-up time will provide a more robust estimate than any single study alone that better inform pediatric ART programs in SSA countries. It also helps policy makers and program managers to make informed decisions to prevent deaths among pediatric ART patients at different follow-up periods. However, the pooled estimates should be interpreted with caution.

This review also has some strengths. First, mortality estimates at different time periods has never been addressed suitably by the available albeit limited systematic reviews conducted on retention or attrition (combining death and LTFU) among children after enrollment in ART. Our study fills this gap by offering mortality estimates at different time periods after initiation on ART to inform pediatric HIV programs in SSA. Second, we have conducted multiple sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of studies with high sample size cohorts, high rate of LTFU, and missing data for any time period on the estimated pooled proportion of mortality at different follow-up periods. Third, we have conducted sub-regional analysis to minimize heterogeneity and provide pooled estimates of mortality by sub-regional settings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our review indicated that there is high rate of early childhood mortality in the first 3–6 months of ART initiation in SSA that calls for thorough screening and management of opportunistic infections before ART initiation. The review showed some degree of variability on mortality estimates of pediatric cohorts enrolled in ART in the Eastern and Western parts of SSA. The information gap on the long-term outcome (mortality) of ART among pediatric cohorts in SSA demands future investigation. Efforts to track LTFU should be strengthened to understand the outcome of pediatric ART patients. Immediate ART initiation among children under the current “test and treat” strategy should be accompanied by strategies for early identification of HIV-infected children in SSA.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral Therapy

- CROI:

-

Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- LTFU:

-

Loss to Follow-Up

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- PLHIV:

-

People Living with HIV

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UNAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Violari A, Paed FC, Cotton MF, Med M, Babiker AG, Jean-Philippe P. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–44.

Puthanakit T, Bunupuradah T. Early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy in children in low-income and middle-income countries. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(1):12–7.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/en/

The INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. 2015. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26192873. [cited 2018 Aug 22]

Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, Morris SR, Mehta SR, Gianella S, et al. Rapid HIV Viral Load Suppression in those Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy at First Visit after HIV Diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32947.

World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing Hiv Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://www.deslibris.ca/ID/10089566. [cited 2018 Aug 22]

UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/909090. [cited 2019 Jan 3]

Fox MP, Rosen S. Systematic review of retention of pediatric patients on HIV treatment in low and middle-income countries 2008-2013. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29(4):493–502.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647.

U.S Department of Health and Human Services National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. [cited 2018 Aug 23].

Ben-Farhat J, Schramm B, Nicolay N, Wanjala S, Szumilin E, Balkan S, et al. Mortality and clinical outcomes in children treated with antiretroviral therapy in four African vertical programmes during the first decade of paediatric HIV care, 2001-2010. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2017;22(3):340–50.

Ebissa G, Deyessa N, Biadgilign S. Predictors of early mortality in a cohort of HIV-infected children receiving high active antiretroviral treatment in public hospitals in Ethiopia. AIDS Care. 2015;27(6):723–30.

Ebonyi AO, Oguche S, Meloni ST, Sagay SA, Kyriacou DN, Achenbach CJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in a clinic cohort of HIV-1 infected children initiated on antiretroviral therapy in Jos, Nigeria. 2014

Njom Nlend AE, Loussikila AB. Predictors of mortality among HIV-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Med Mal Infect. 2017;47(1):32–7.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607–11.

Lamb MR, Fayorsey R, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Viola V, Mutabazi V, Alwar T, et al. High attrition before and after ART initiation among youth (15-24 years of age) enrolled in HIV care. AIDS Lond Engl. 2014;28(4):559–68.

Davies M-A, May M, Bolton-Moore C, Chimbetete C, Eley B, Garone D, et al. Prognosis of children with HIV-1 infection starting antiretroviral therapy in southern Africa: a collaborative analysis of treatment programs. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):608–16.

Melaku Z, Lulseged S, Wang C, Lamb MR, Gutema Y, Teasdale CA, et al. Outcomes among HIV-infected children initiating HIV care and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2017;22(4):474–84.

Porter M, Davies M-A, Mapani MK, Rabie H, Phiri S, Nuttall J, et al. Outcomes of Infants Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in Southern Africa, 2004–2012. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2015;69(5):593–601.

Brophy JC, Hawkes MT, Mwinjiwa E, Mateyu G, Sodhi SK, Chan AK. Survival outcomes in a pediatric antiretroviral treatment cohort in southern Malawi. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165772.

Ojikutu B, Higgins-Biddle M, Greeson D, Phelps BR, Amzel A, Okechukwu E, et al. The association between quality of HIV care, loss to follow-up and mortality in pediatric and adolescent patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e100039.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Harbord RM, Harris RJ, Sterne JAC. Updated tests for small–study effects in meta–analyses STATA J. 2009. Available from: https://www.stata-journal.com/article.html?article=sbe19_6. [cited 2018 Sep 13]

Sterne JAC, Harbord RM. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. Stata J. 2004;4(2):127–41.

Vermund SH, Blevins M, Moon TD, José E, Moiane L, Tique JA, et al. Poor clinical outcomes for HIV infected children on antiretroviral therapy in rural Mozambique: need for program quality improvement and community engagement. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110116.

Abrams EJ, Woldesenbet S, Soares Silva J, Coovadia A, Black V, Technau K-G, et al. Despite access to Antiretrovirals for prevention and treatment, high rates of mortality persist among HIV-infected infants and young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(6):595–601.

Lilian RR, Mutasa B, Railton J, Mongwe W, McINTYRE JA, Struthers HE, et al. A 10-year cohort analysis of routine paediatric ART data in a rural south African setting. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(1):170–80.

Marazzi MC, De Luca S, Palombi L, Scarcella P, Ciccacci F, Ceffa S, et al. Predictors of adverse outcomes in HIV-1-infected children receiving combination antiretroviral treatment: results from a DREAM cohort in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(3):295–300.

Andargie AA, Asmleash Y. Survival time of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected children under 15 years of age after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. J AIDS HIV Res. 2018;10(4):49–55.

Anigilaje EA, Aderibigbe SA. Mortality in a cohort of HIV-infected children: a 12-month outcome of antiretroviral therapy in Makurdi, Nigeria. Adv Med. 2018;2018:6409134.

Auld AF, Alfredo C, Macassa E, Jobarteh K, Shiraishi RW, Rivadeneira ED, et al. Temporal trends in patient characteristics and outcomes among children enrolled in Mozambique’s National Antiretroviral Therapy Program. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(8):e191–9.

Auld AF, Tuho MZ, Ekra KA, Shiraishi RW, Mohamed F, Kouakou JS, et al. Temporal trends in mortality and loss to follow-up among children enrolled in Côte d’Ivoire’s national antiretroviral therapy program. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(11):1134–40.

Biru M, Hallström I, Lundqvist P, Jerene D. Rates and predictors of attrition among children on antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0189777.

Ditekemena J, Luhata C, Bonane W, Kiumbu M, Tshefu A, Colebunders R, et al. Antiretroviral treatment program retention among HIV-infected children in the Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e113877.

Edessa D, Asefa F, Sheikahmed J. Early mortality among HIV-positive children initiated anti-retroviral therapy in eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2015;4(2):157–63.

Kedir AA, Desta A, Fesseha G. Factors affecting survival of HIV positive children taking antiretroviral therapy at Adama Referral Hospital and Medical College, Ethiopia. J AIDS Clin Res. 2014;5(3) Available from: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20143213012. [cited 2018 Aug 11].

McHugh G, Simms V, Dauya E, Bandason T, Chonzi P, Metaxa D, et al. Clinical outcomes in children and adolescents initiating antiretroviral therapy in decentralized healthcare settings in Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21843.

Mulugeta A, Assefa H, Tewelde T, Dube L. Determinants of survival among HIV positive children on antiretroviral therapy in public hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Qual Prim Care. 2017;25(4):235–41.

Naik NM, Bacha J, Gesase AE, Barton T, Schutze GE, Wanless RS, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in children less than 24 months of age at pediatric HIV centers in Tanzania: 12-month clinical outcomes and survival. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2016;15(5):440–8.

Ojeniran MA, Emokpae A, Mabogunje C, Akintan P. How are children with HIV faring in Nigeria?- a 7 year retrospective study of children enrolled in HIV care. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:87.

Teasdale CA, Sogaula N, Yuengling KA, Peters ZJ, Mutiti A, Pepeta L, et al. High risk of loss to follow-up among South African children on ART during transfer, a retrospective cohort analysis with community tracing. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21748.

Sidamo N, Debere M, Enderis B, Abyu D. Incidence and predictors of mortality among children on anti-retroviral therapy in public health facilities of Arba Minch town, Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia; retrospective cohort study. Clin Mother Child Health. 2017;14:3.

Mokgatle MM, Abasho DC. Treatment outcomes of antiretroviral therapy among pediatric patients in Zewditu memorial hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PULA: Botswana J Afr Stud. 2016;30(1):11.

WHO. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Infants and Children: Towards Universal Access: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: 2010 Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Burrage A, Patel M, Mirkovic K, Dziuban E, Teferi W, Broyles L, et al. Trends in antiretroviral therapy eligibility and coverage among children aged <15 years with HIV infection — 20 PEPFAR-supported sub-Saharan African countries, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(19):552–5.

KIDS-ART-LINC Collaboration. Low risk of death, but substantial program attrition, in pediatric HIV treatment cohorts in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2008;49(5):523–31.

Ciaranello AL, Chang Y, Margulis AV, Bernstein A, Bassett IV, Losina E, et al. Effectiveness of pediatric antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(12):1915–27.

Abuogi LL, Smith C, McFarland EJ. Retention of HIV-Infected Children in the First 12 Months of Anti-Retroviral Therapy and Predictors of Attrition in Resource Limited Settings: A Systematic Review. Okulicz JF, editor. Plos One. 2016;11(6):e0156506.

Ndondoki C, Dabis F, Namale L, Becquet R, Ekouevi D, Bosse-Amani C, et al. Survival, clinical and biological outcomes of HIV-infected children treated by antiretroviral therapy in Africa: systematic review, 2004–2009. Presse Medicale Paris Fr 1983. 2011;40(7–8):e338–57.

Castelnuovo B, Manabe YC, Kiragga A, Kamya M, Easterbrook P, Kambugu A. Cause-specific mortality and the contribution of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in the first 3 years after antiretroviral therapy initiation in an urban African cohort. 2009; Available from: http://makir.mak.ac.ug/handle/10570/279. [cited 2018 Sep 26]

Smith K, Kuhn L, Coovadia A, Meyers T, Hu C-C, Reitz C, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome among HIV-infected south African infants initiating antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Lond Engl. 2009;23(9):1097–107.

Haddow LJ, Moosa M-YS, Mosam A, Moodley P, Parboosing R, Easterbrook PJ. Incidence, clinical spectrum, risk factors and impact of HIV-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(11) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3495974/. [cited 2018 Sep 26].

Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M. Incidence and lethality of immune reconstitution disease in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):251–61.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professor Alemayehu Worku, from Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University for his critical review of the results and guidance throughout the process of conducting the study. We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Salem T. Gugsa, from Department of Global Health, University of Washington for her critical review and comment on the protocol of this study. We are also immensely grateful to Anjali Sharma from the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia for her technical support in refining the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they did not receive funding for this research from any source.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA had primary responsibility in conceptualization, protocol development, data extraction and analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript drafting and revision. SL participated in the revision of study protocol, study selection, interpretation of results, and manuscript revision. Both authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ information

IA: MPH; Chief Public Health Professional, PhDc at University of Gondar, Ethiopia. He has expertise in HIV/AIDS program and research. SL: MPH, PhD; Research Fellow at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, based at Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She has expertise in research.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Databases used and exact search terms. (DOCX 22 kb)

Additional file 2:

Quality assessment results for each cohort study included in the review using Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies provided by the U.S Department of Health and Human Services. (DOCX 126 kb)

Additional file 3:

Begg’s funnel plots to assess publication bias of studies by reporting duration. A) Studies reporting to 6 months ART follow-up (n = 14). B) Studies reporting to 12 months ART follow-up (n = 17). C) Studies reporting to 24 months ART follow-up (n = 10). (DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, I., Lemma, S. Mortality among pediatric patients on HIV treatment in sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 19, 149 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6482-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6482-1