Abstract

Background

Multiple risk behaviour (MRB) refers to two or more risk behaviours such as smoking, drinking alcohol, poor diet and unsafe sex. Such behaviours are known to co-occur in adolescence. It is unknown whether MRB interventions are equally effective for young people of low and high socioeconomic status (SES). There is a need to examine these effects to determine whether MRB interventions have the potential to narrow or widen inequalities.

Methods

Two Cochrane systematic reviews that examined interventions to reduce adolescent MRB were screened to identify universal interventions that reported SES. Study authors were contacted, and outcome data stratified by SES and intervention status were requested. Risk behaviour outcomes alcohol use, smoking, drug use, unsafe sex, overweight/obesity, sedentarism, peer violence and dating violence were examined in random effects meta-analyses and subgroup analyses conducted to explore differences between high SES and low SES adolescents.

Results

Of 49 studies reporting universal interventions, only 16 also reported having measured SES. Of these 16 studies, four study authors provided data sufficient for subgroup analysis. There was no evidence of subgroup differences for any of the outcomes. For alcohol use, the direction of effect was the same for both the high SES group (RR 1.26, 95% CI: 0.96, 1.65, p = 0.09) and low SES group (RR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.32, p = 0.08). The direction of effect was different for smoking behaviour in favour of the low SES group (RR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.66, 1.03, p = 0.09) versus the high SES group (RR 1.16, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.63, p = 0.39). For drug use, the direction of effect was the same for both the high SES group (RR 1.29, 95% CI: 0.97, 1.73, p = 0.08) and the low SES group (RR 1.28, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.96, p = 0.25).

Conclusions

The majority of studies identified did not report having measured SES. There was no evidence of subgroup difference for all outcomes analysed among the four included studies. There is a need for routine reporting of demographic information within studies so that stronger evidence of effect by SES can be demonstrated and that interventions can be evaluated for their impact on health inequalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Risk behaviours such as smoking, alcohol consumption, drug misuse, risky sexual behaviour, unhealthy diet and low levels of physical activity co-occur in adolescence [1, 2]. Multiple risk behaviour (MRB) refers to the occurrence of two or more risk behaviours directly or indirectly related to health [3]. Recognising the co-occurrence of risk behaviours, there has been a number of public health interventions that address MRB as opposed to single behaviours in isolation [4]. The rationale behind this approach being that strategies may affect more than one outcome, proving more efficient and cost-effective [5]. Interventions targeting one behaviour may be less successful as they do not address the co-occurrence of behaviours [6]. The fact that most adults claim to have initiated risk behaviours during adolescence indicates that intervening early may be the best approach [7].

The inverse relationship between risk behaviour and socioeconomic status (SES) has been widely reported [8,9,10]. In response, strategies to improve health behaviour of young people have often targeted low SES groups. However, targeting ignores the social gradient to health and may result in stigma or failing to reach at-risk schools or pupils [11]. Thus, some researchers argue for ‘proportionate universalism’ [12] as “universal interventions which disproportionally benefit low SES groups may have the greatest potential to improve population health, while reducing inequality” [11]. However, proportionate universalism has potential challenges that have not been tested in practise, such as assessing the proportion of resource that should be allocated to each level of disadvantage [13].

It has been raised by a number of researchers, including those working in the Cochrane Equity Methods Group [14, 15], that universal public health interventions have the potential to increase inequalities in the population [15,16,17]. This occurs when the interventions are of greater benefit to the most advantaged groups, inadvertently increasing inequalities (the inverse equity hypothesis) [17, 18]. White et al. [19] state that all processes in the planning and delivery of public health strategies have the potential to create intervention generated inequalities. For instance, if a survey is used to assess need for a public health intervention, variation in response rates by socioeconomic status could underestimate the need among the most disadvantaged groups [19, 20]. Compliance with the intervention programme may also be higher in groups with higher SES who have greater access to resources such as time, coping skills and finance that enable them to take advantage of the intervention [16].

There are increasing initiatives to encourage more comprehensive reporting of factors that can lead to health inequalities [17]. PROGRESS-Plus is a proposed framework for the PRISMA Equity Extension, used to identify characteristics that stratify health opportunities and outcomes [17]. The acronym refers to the following: place of residence; race/ethnicity/culture/language; occupation; gender/sex; religion; education; socioeconomic status and social capital, with the ‘Plus’ element referring to personal discriminating characteristics (e.g. age, disability), features of relationships (e.g. smoking parents) and time-dependent relationships (e.g. leaving the hospital, temporary disadvantage) [17]. Although this framework is now widely adopted and has been endorsed by the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group [21], there is still limited evidence about intervention generated inequalities from systematic reviews. This is in part due to the studies under review failing to record such demographic information in the first instance [22].

Whereas reviews have been undertaken to assess inequalities with regard to single behaviours such as healthy eating [16, 22] physical activity [23], smoking tobacco [24], no study has yet explored differential intervention effects with regard to MRB interventions. This study re-examines studies from two Cochrane systematic reviews of adolescent MRB interventions [4, 6] for differential outcome effects by socioeconomic status. The aim was to identify whether public health interventions for adolescent MRB increase or reduce inequalities. It was also an aim of the study to determine the extent to which SES is reported within adolescent MRB studies and the types of measures used.

Methods

Study design

We conducted secondary analyses of studies included in two Cochrane systematic reviews that focused on adolescent MRB [4, 6]. These reviews included randomised controlled trails (RCTs) and cluster RCTs. The reviews examined the effects of interventions implemented up to 18 years of age for the primary or secondary prevention of multiple risk behaviours. The interventions could be individual, family, or school-based interventions. Risk behaviours included: tobacco use; alcohol consumption; illicit drug use; risky sexual behaviours; anti-social behaviour and offending; vehicle-related risk behaviours; self-harm; gambling; unhealthy diet; high levels of sedentary behaviour; and low levels of physical activity. Both reviews followed the robust procedures specified by the Cochrane Collaboration and the interested reader is referred to the protocols for further details [4, 6]. The literature searches for these reviews were conducted in 2012 and 2015.

Inclusion criteria and screening for current analysis

Studies were eligible for the current paper if they met the initial inclusion criteria for the Cochrane reviews on adolescent MRB [4, 6]. Additionally, studies were restricted to universal interventions (i.e. aimed at a whole population, such as a school) [11], as interventions that target specific demographic or high-risk groups would be unable to detect difference in effect by SES. If a study was described as universal, but participants were predominantly from one socioeconomic group, it was excluded from this analysis. Full text studies were then screened to determine if any reported having measured SES at baseline and/or conducted a subgroup analysis by SES. SES is broadly defined to include a range of indicators such as: parental education, parental income, parental occupation, free school meal eligibility, Hollingshead index [25] and receipt of social benefit. Other demographic indicators outlined by the PROGRESS-Plus [17] model such as gender and ethnicity were not included in this analysis.

Data extraction and management

SES data were extracted by one reviewer and input into a predesigned form; additional data on intervention design, setting, population, and outcome(s) were taken from the Characteristics of Studies tables produced for [4, 6]. Authors of the study papers that reported having measured SES at baseline were contacted and asked to provide additional detail on the outcomes by SES and intervention assignment (i.e. experimental or control). Authors were also given the option to send the cleaned dataset if they preferred. Those contacted were given several weeks to respond and reminder emails were sent.

Data analysis

Following the procedure of project TEENAGE [26], SES measures were dichotomized into high SES (parent with degree-level education, not eligible for free school meals) and low SES (parent without a degree-level education, eligible for free school meals). Studies were combined using a random effects meta-analysis and sub-group analyses performed using Revman 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen 2014). Random-effects models were specified a priori due to anticipated between-study heterogeneity with regard to settings and participants [27]. Subgroup-specific effect estimates are summarised as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and are presented in forest plots by dichotomised SES subgroup. We do not report the overall pooled summary effect (i.e. the two subgroups combined) since the studies included here are a subset of those included in the original Cochrane reviews. An overall pooled effect would therefore be misleading. Subgroup-specific intervention effects are compared using a test for interaction rather than comparison of significance through p-values [27]. The test for interaction is undertaken using Cochran’s Q and Higgins I2. [28, 29]. Outcomes only examined by a single study, are reported in the text.

Results

Description of included studies

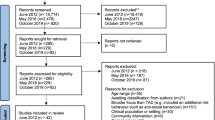

Figure 1 presents the flow chart of included studies which, for transparency, includes the screening process for the ancestor Cochrane systematic reviews. Following the full text screening of 101 eligible studies (published between 1982 and 2015) from the parent Cochrane reviews, 49 studies met the criterion of being universal and not targeted to a specific group. Of those universal studies, 16 reported measuring SES and were therefore eligible for secondary analysis for the current paper and authors were contacted for additional data on SES. These studies are included in Table 1, along with descriptive information on: study name, setting, population, intervention properties, primary outcome(s), SES indicator used, effect of intervention, differential effect by SES and risk of bias assessments. Studies were conducted in the following countries: USA (n = 12), UK (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Spain and Mexico collaboration (n = 1) and Sweden (n = 1). Of the 16 eligible studies, the following types of intervention were described, with some studies adopting more than one intervention element: school-based curriculum, workshop, training or problem solving (n = 13), family or parent training or support (n = 5), adult mentoring programme (n = 1), website and text service (n = 1), practice nurse session (n = 1). Details and reasons for study exclusion are listed in Table 2 and Table 3 in Appendix 1 and 2.

Measures of SES

A range of SES measures was employed across the studies, with some using more than one SES measure. The most commonly used measure of SES was free school meal eligibility (n = 7), with one study also including reduced-price school meal eligibility. Parental education (n = 5) and parental/household income (n = 5) were the second most common, with one study specifying maternal education. None of the studies gave a rationale for their choice of SES measure.

Subgroup analyses by SES

Of the 16 authors contacted for further data, nine authors did not respond and three did not have the data available in a suitable format to re-run analyses. Consequently, only four studies could be included in the secondary analysis. Of these, two were conducted in the USA, one in Canada and one as a collaboration between Spain and Mexico. All were school-based. All four studies measured alcohol use as a primary outcome, with other outcomes including tobacco smoking (n = 3), drug use (n = 3) with two studies measuring any illicit drug use and one measuring cannabis use, unsafe sex (n = 1), overweight/obese (n = 1), sedentarism (n = 1) dating violence (n = 1) and peer violence (n = 1). Two studies measured SES using free school meal eligibility and two used parental education as a proxy for adolescent SES. For alcohol, measured by all studies, the total number of participants in the subgroup analysis was 1720 in the high SES group and 1657 in the low SES group.

We report subgroup analyses in Fig. 2 for alcohol, Fig. 3 smoking and Fig. 4 drug use. The maximum number of studies included is 4. For all three outcomes there was an absence of evidence for subgroup differences by high or low SES: alcohol use (χ2 = 0.40, df = 1 (p = 0.53) I2 = 0%), smoking (χ2 = 2.68, df = 1 (p = 0.10) I2 = 62.7%) and drug use (χ2 = 0.00, df = 1 (p = 0.98) I2 = 0%). Due to the small numbers of studies included, these results should be interpreted with caution and may represent false negatives due to inadequate power.

Forest plot of meta regression analysis for outcome alcohol by SES group. The plot shows the data meta-analysed in two subgroups (high SES: parent with a degree or ineligible for free school meals) (low SES: parents do not have a degree or young person eligible for free school meals). The boxes represent the estimates and the arrows coming out of the boxes the 95% confidence intervals. The diamond is the pooled estimate for each subgroup. The overall pooled estimate is not shown as the figure is concerned with comparing the two groups. Estimates on the right-hand side of the figure labelled ‘favours control’ equates to an increase in negative alcohol behaviour while the ‘favours intervention’ arm refers to a reduction in negative alcohol behaviour following intervention

Forest plot of meta regression analysis for outcome smoking by SES group. The plot shows the data meta-analysed in two subgroups (high SES: parent with a degree or ineligible for free school meals) (low SES: parents do not have a degree or young person eligible for free school meals). The boxes represent the estimates and the arrows coming out of the boxes the 95% confidence intervals. The diamond is the pooled estimate for each subgroup. The overall pooled estimate is not shown as the figure is concerned with comparing the two groups. Estimates on the right-hand side of the figure labelled ‘favours control’ equates to an increase in smoking behaviour while the ‘favours intervention’ arm refers to a reduction in smoking behaviour following intervention

Forest plot of meta regression analysis for outcome drug use by SES group. The plot shows the data meta-analysed in two subgroups (high SES: parent with a degree or ineligible for free school meals) (low SES: parents do not have a degree or young person eligible for free school meals). The boxes represent the estimates and the arrows coming out of the boxes the 95% confidence intervals. The diamond is the pooled estimate for each subgroup. The overall pooled estimate is not shown as the figure is concerned with comparing the two groups. Estimates on the right-hand side of the figure labelled ‘favours control’ equates to an increase in drug use while the ‘favours intervention’ arm refers to a reduction in drug use following intervention

The point estimates for alcohol use show that SES does not explain the effect of the intervention, as the direction of effect is the same for both high SES (RR 1.26, 95% CI: 0.96, 1.65, p = 0.09) and low SES (RR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.32, p = 0.08). The confidence intervals for both groups’ pooled estimates cross the null.

For smoking the point estimates are indicative of a differential intervention effect in favour of the low SES group (RR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.66, 1.03, p = 0.09) versus the high SES group (RR 1.16, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.63, p = 0.39). The confidence intervals in both groups crossed the null.

For drug use, SES was not an explanatory factor for the intervention effect as the direction of effect in the high SES group (RR 1.29, 95% CI: 0.97, 1.73, p = 0.08) and the low SES group (RR 1.28, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.96, p = 0.25) was the same. The confidence intervals in both groups crossed the null.

Only 1 study reported outcomes related to peer and dating violence [30]. Analysis revealed no evidence of a difference between the SES groups within the individual study for peer violence (χ2 = 2.37, df = 2, p = 0.31, I2 = 15.6%) or dating violence (χ2 = 1.91, df = 2, p = 0.38, I2 = 0%). The point estimates suggested a beneficial intervention effect regarding dating violence for high SES young people (RR 0.49, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.86, p = 0.01) and an insufficient intervention effect for low SES adolescents (RR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.50, 1.14, p = 0.51). The direction of effect was the same for peer violence in Wolfe et al.’s [30] study: high SES adolescents (RR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.58, 1.25, p = 0.40) and low SES adolescents (RR 1.32, 95% CI: 0.88, 1.99, p = 0.18).

Only 1 study reported the outcome overweight/obesity [31]. The test for subgroup differences revealed no difference between the SES groups within the individual study (χ2 = 0.98, df = 2, p = 0.61, I2 = 0%). The point estimates suggested a differential intervention effect in favour of the low SES group (RR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.42, 1.80, p = 0.71). For sedentarism, examined in the same isolated study, the point estimates indicated that SES did not explain difference in the intervention effect as both were in the same direct: high SES (RR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.55, 1.07, p = 0.12) low SES: (RR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.47, 1.41, p = 0.47). The confidence intervals for the effect in both groups crossed the null.

Discussion

Through a secondary analysis of intervention effects by socioeconomic status in adolescent MRB interventions, we found there to be sparse reporting of demographic characteristics needed to investigate inequalities.

Despite the recognition that interventions may increase or reduce inequalities, concerns have been raised that most evaluations do not assess the differential impact by socioeconomic group [11, 32]. Many studies do not record the demographic information needed for subgroup analysis, or are insufficiently powered [16, 22, 33]. Moore et al. [11] suggest that this inattention to inequality within public health interventions may reflect a utilitarian perspective in focusing on achieving the greatest benefit for the most amount of people. Lynch et al. [34] address this idea through a discussion of ‘absolute’ and ‘relative’ inequality. They note that if the aim is to reduce relative inequalities in an outcome, the absolute benefit to the population may be small, particularly if the outcome is equally common in all groups [34]. Therefore, for some outcomes there may be a conflict in attempting to improve health for all young people while also reducing inequalities.

There was variation in how SES is measured in the eligible studies, with no justification for the choice of measure in any of the full text papers [11]. This study supports Moore et al. [11] in illustrating the need for greater consensus upon SES measures to ensure more reliable studies. Even those studies that used the same SES measure may have employed it slightly differently, for example, only measuring mother or father’s education or including reduced-priced school meal eligibility as well as free school meals. A consensus on a single SES measure, however, may not be easily reached due to significant disagreements on definitions and theoretical assumptions [35]. For example, the most common measure in the eligible studies, free school meal eligibility, is often used a proxy of SES as it is easily accessible and inexpensive to record compared with parental education and household income [35]. However, the threshold for eligibility may differ between countries and regions and some authors have found free school meal eligibility to inadequately reflect household income [35, 36].

The Family Influence Scale (FAS) has been implemented in the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study, as well as other research and policy work as a measure of SES within adolescence [37]. FAS is comprised of easily answerable indicators of affluence and consumption, such as number of cars, young people having their own bedroom and the number of holidays the family take. Studies adopting FAS have reported low levels of missing data of around 2% [37,38,39] and have shown low affluence to be associated with outcomes such as increased risk of fighting injury [40] and higher consumption soft drinks compared to high affluence young people [41]. FAS thus presents a possible indicator for assessing inequalities in interventions that target adolescents. Although, there are limitations such as the need to adapt the scale dependent on country and consumer patterns [37] and most validation work has been done within cross-sectional studies [37].

The point estimates for alcohol use show that SES does not explain the effect of the intervention as the direction of effect is the same for both SES groups, indicating that these interventions neither increase nor reduce inequalities. However, there was a lack of evidence of subgroup difference, so these findings are indicative. The point estimates favoured the control group, which is noteworthy as the findings from the meta-analysis from one of the original MRB systematic reviews reported universal school-based interventions to have a beneficial effect for young people in relation to alcohol use [42]. One reason for this difference in findings could be that this present subgroup analyses had only four studies. Two of the four studies [31, 43] in the subgroup analysis had small samples and low numbers of events, meaning that the pooled estimates were heavily weighted toward the other two studies. The original systematic review from which these studies were taken, however, meta-analysed eight studies with 8751 participants in total [42] demonstrating that such interventions probably have a beneficial effect in relation to alcohol. Thus, it is further evident that there is a need for greater reporting of demographic characteristics so that health inequalities in interventions might be examined more comprehensively.

For tobacco smoking, there was an indication of a different direction of effect between the groups, in favour of the low SES group. The confidence intervals cross the null in these analyses and there is no evidence of subgroup differences. However, this finding highlights the potential for interventions to have differential effects for different groups. Reviews with more studies and greater power are needed to investigate this further, as the thinking that universal interventions tend to benefit those from high SES the most [11, 15] might not always be the case. The intervention effect on inequalities may depend on the setting, the intervention type and the outcomes being examined. A systematic review that assessed the equity impact of tobacco interventions and policies on young people found that price increase of cigarettes had the most consistent positive impact [44]. However, the review found very few studies that examined intervention inequalities among young people and called for the evidence base to be strengthened [44]. Therefore, there is a need for greater exploration of the types of interventions (upstream or downstream) and intervention elements that may decrease inequalities in MRB in young people.

For Wolfe et al.’s [30] study, the school-based training intervention, the direction of effect was different between groups for outcomes dating violence and peer violence, in favour of the high SES group. In the overall sample Wolfe et al. [45] reported a beneficial effect for both dating violence and peer violence. This finding represents one example of an intervention that is successful at a population level, yet may potentially increase inequalities through disproportionately benefiting the least deprived adolescents. The fact that the intervention under evaluation was a downstream intervention, focusing on individual behaviour change, chimes with current thinking around intervention generated inequalities [15, 46]. However, this example should be treated as illustrative as it only presents one study and there was no evidence of subgroup difference between the low SES and high SES groups.

This present study supports previous research in highlighting the limited evidence base on the differential effect of interventions by socioeconomic status. Researchers have cited similar difficulties in being able to find studies that conduct subgroup analyses, that measure socioeconomic variables at baseline or that are powered to detect differences by demographic groups [11, 15, 22, 46]. The TEENAGE project reanalysed interventions targeting any of four risk behaviours (smoking, diet, physical activity and alcohol) for differential effects by SES, but was limited by the small number of studies that collected demographic information [26, 47]. Moore et al. [11] conducted a systematic review of school-based health interventions but could only draw tentative conclusions due to a small sample and called for more routine testing of effects of interventions on inequality. While our study was also unable to detect evidence of difference due to a small sample, it provides an indication of how interventions may affect different SES groups differently.

This study highlights that work still needs to be done to encourage intervention leaders and systematic reviewers to record and analyse PROGRESS-Plus demographic information. The fact that only a small proportion of identified interventions measured SES at baseline, and none conducted SES sub-group analysis, further illuminates the lack of evidence regarding intervention generated inequalities [19]. This present study also highlights the importance of researchers keeping datasets accessible and being willing to engage in re-analysis.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the systematic approach to reviewing public health interventions for differential outcome effect by SES. To our knowledge this is the first of its kind to conduct secondary analysis on universal interventions aimed at adolescent multiple risk behaviour using Cochrane systematic reviews. The approach could be applied for other public health interventions looking at different outcomes in different age groups. This study also demonstrates potential research that can be done to investigate health inequalities using existing systematic reviews at relatively low cost. It further highlights the need to consider health inequalities in the development of public health interventions so that appropriate subgroup analyses and meta-analyses are possible to detect differential effects by different SES groups.

Secondary analyses were only performed on a small sample of studies, most of which were not initially designed or sufficiently powered to investigate inequalities. Post hoc subgroup analyses can be unreliable and misleading [48]; however, not performing them would be a lost opportunity in terms of investigating health inequalities [46]. Most of the studies were conducted in North America, which makes generalizability difficult due to the different ways SES affects health cross-nationally [11, 46], for instance with regard to the racialisation of inequality in North America [11]. Many of the interventions included in the Cochrane systematic reviews were at least 10 years old so it is possible that the collection and reporting of demographic variables to trace intervention generated inequalities is occurring in more contemporary studies not captured by these reviews. We were unable to find any study protocols, so we are unaware if some studies intended to collect SES data but did not publish the findings. Therefore, selective outcome reporting could be a problem among the included studies [49].

There was considerable heterogeneity among the studies regarding design and statistical methodology. There was also variation in the type of SES measure used, making comparability a challenge [50].

Another limitation that has been cited in similar studies [46] is that all of the interventions re-analysed were ‘downstream’ interventions. Thus, we are unable to compare upstream and downstream interventions in their impact on health inequalities, which would be preferable as it has been hypothesized that ‘upstream interventions’ may be the most successful in reducing inequality [15]. Had we included other study designs, such as natural experiments, we may have been able to explore more upstream interventions as well as studies that specifically look at the effect of interventions on inequalities [51].

There was socially patterned attrition in some of the included studies, meaning that the low SES groups often had fewer participants than high SES groups. The behaviour outcome measures were also self-report, which may lead to less valid completion among some demographic groups and thus lack the sensitivity to detect differential effects [11, 52].

There is the additional measurement problem when studying inequalities in young people. If parental measures of SES are used as proxy and are self-report by their children, they may not know the educational attainment or occupation of their parents [37, 53]. It is likely there will be missing data that are socially patterned, with higher SES young people being more aware of their parents’ education and occupation than low SES young people [37].

Conclusions

The majority of studies identified did not report having measured SES. There was little consistency of SES measure used and rarely were demographics reported for the purposes of subgroup analyses, meaning that this study was underpowered to detect subgroup differences. There is a need for routine reporting of demographic information within studies so that stronger evidence of effect by SES can be demonstrated and interventions evaluated for their impact on health inequalities.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- FAS:

-

Family Affluence Scale

- HBSC :

-

Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children

- MRB:

-

Multiple Risk Behaviour

- N:

-

Number

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RR:

-

Relative Risk

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic Status

References

Kipping R, Campbell RM, MacArthur G, Gunnell D, Hickman M. Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence. Journal of Public Health. 2012;34(suppl 1):i1–2.

Spring B, Moller AC, Coons MJ. Multiple health behaviours: overview and implications. J Public Health. 2012;34(suppl 1):i3–i10.

Hurrelmann K, Richter M. Risk behaviour in adolescence: the relationship between developmental and health problems. J Public Health. 2006;14(1):20–8.

Hickman M, Caldwell DM, Busse H, MacArthur G, Faggiano F, Foxcroft DR, Kaner EF, Macleod J, Patton G, White J. Individual-, family-, and school-level interventions for preventing multiple risk behaviours relating to alcohol, tobacco and drug use in individuals aged 8 to 25 years. Cochrane Libr. 2014.

Buck D, Frosini F. Clustering of unhealthy behaviours over time. London: The Kings Fund. 2012:1–24.

MacArthur G, Kipping R, White J, Chittleborough C, Lingam R, Pasch K, Gunnell D, Hickman M, Campbell R. Individual-, family-, and school-level interventions for preventing multiple risk behaviours in individuals aged 8 to 25 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6.

Jackson C, Sweeting H, Haw S. Clustering of substance use and sexual risk behaviour in adolescence: analysis of two cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000661.

Kipping RR, Smith M, Heron J, Hickman M, Campbell R. Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and socio-economic status: findings from a UK birth cohort. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(1):44–9.

Lemstra M, Bennett NR, Neudorf C, Kunst A, Nannapaneni U, Warren LM, Kershaw T, Scott CR. A meta-analysis of marijuana and alcohol use by socio-economic status in adolescents aged 10-15 years. Can J Public Health. 2008:172–7.

Drieskens S, Van Oyen H, Demarest S, Van der Heyden J, Gisle L, Tafforeau J. Multiple risk behaviour: increasing socio-economic gap over time? Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(6):634–9.

Moore GF, Littlecott HJ, Turley R, Waters E, Murphy S. Socioeconomic gradients in the effects of universal school-based health behaviour interventions: a systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):907.

Marmot M, Atkinson T, Bell J, Black C, Broadfoot P, Cumberlege J, Diamond I, Gilmore I, Ham C, Meacher M et al: Fair society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review. In.; 2010.

Egan M, Kearns A, Katikireddi SV, Curl A, Lawson K, Tannahill C. Proportionate universalism in practice? A quasi-experimental study (GoWell) of a UK neighbourhood renewal programme's impact on health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2016;152:41–9.

Mbuagbaw L, Aves T, Shea B, Jull J, Welch V, Taljaard M, Yoganathan M, Greer-Smith R, Wells G, Tugwell P. Considerations and guidance in designing equity-relevant clinical trials. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):93.

Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(2):190–3.

McGill R, Anwar E, Orton L, Bromley H, Lloyd-Williams F, O’Flaherty M, Taylor-Robinson D, Guzman-Castillo M, Gillespie D, Moreira P, et al. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):457.

O'Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, Petticrew M, Pottie K, Clarke M, Evans T, Pardo JP, Waters E, White H. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):56–64.

Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet. 2000;356(9235):1093–8.

White M, Adams J, Heywood P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations. Soc Inequal Public Health. 2009:65–82.

Turrell G, Patterson C, Oldenburg B, Gould T, Roy M-A. The socio-economic patterning of survey participation and non-response error in a multilevel study of food purchasing behaviour: area-and individual-level characteristics. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(2):181–9.

Tugwell P, Petticrew M, Robinson V, Kristjansson E, Maxwell L. Cochrane and Campbell collaborations, and health equity. Lancet. 2006;367(9517):1128–30.

Oldroyd J, Burns C, Lucas P, Haikerwal A, Waters E. The effectiveness of nutrition interventions on dietary outcomes by relative social disadvantage: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(7):573–9.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Simon C, De Meester F, Van Lenthe F, Spittaels H, Lien N, Faggiano F, Mercken L, Moore L, Haerens L. Are physical activity interventions equally effective in adolescents of low and high socio-economic status (SES): results from the European Teenage project. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(1):119–30.

Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e89–97.

Hollingshead AB: Four factor index of social status. 1975.

van Lenthe FJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Klepp K-I, Lien N, Moore L, Faggiano F, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Preventing socioeconomic inequalities in health behaviour in adolescents in Europe: background, design and methods of project TEENAGE. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):125.

Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. 2011. Availible from: http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 23 Jan 2018.

Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: heterogeneity and subgroup analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f4040.

Borenstein M, Higgins JP. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev Sci. 2013;14(2):134–43.

Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, Chiodo D, Hughes R, Ellis W, Stitt L, Donner A. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(8):692–9.

Lana A, Faya-Ornia G, López ML. Impact of a web-based intervention supplemented with text messages to improve cancer prevention behaviors among adolescents: results from a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2014;59:54–9.

Whitehead M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(6):473–8.

Stronks K. Generating evidence on interventions to reduce inequalities in health: the Dutch case. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30(59_suppl):20–5.

Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper S, Bainbridge K. Explaining the social gradient in coronary heart disease: comparing relative and absolute risk approaches. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):436–41.

Harwell M, LeBeau B. Student eligibility for a free lunch as an SES measure in education research. Educ Res. 2010;39(2):120–31.

Hobbs G, Vignoles A. Is children’s free school meal ‘eligibility’ a good proxy for family income? Br Educ Res J. 2010;36(4):673–90.

Currie CE, Elton RA, Todd J, Platt S. Indicators of socioeconomic status for adolescents: the WHO health behaviour in school-aged children survey. Health Educ Res. 1997;12(3):385–97.

Molcho M, Gabhainn SN, Kelleher CC. Assessing the use of the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) among Irish schoolchildren. Irish Med J. 2007;100(8):37–9.

Wardle J, Robb K, Johnson F. Assessing socioeconomic status in adolescents: the validity of a home affluence scale. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(8):595–9.

Pickett W, Molcho M, Simpson K, Janssen I, Kuntsche E, Mazur J, Harel Y, Boyce WF. Cross national study of injury and social determinants in adolescents. Inj Prev. 2005;11(4):213–8.

Inchley J, Todd J, Bryce C, Currie C. Dietary trends among Scottish schoolchildren in the 1990s. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14(3):207–16.

MacArthur G, Caldwell DM, Redmore J, Watkins SH, Kipping R, White J, Chittleborough C, Langford R, Er V, Lingam R, Pasch K, Gunnell D, Hickman M, Campbell R. Individual‐, family‐, and school‐level interventions targeting multiple risk behaviours in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018. Issue 10. Art. No.: CD009927. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009927.pub2.

Gottfredson DC, Cross A, Wilson D, Rorie M, Connell N. An experimental evaluation of the all stars prevention curriculum in a community after school setting. Prev Sci. 2010;11(2):142–54.

Brown T, Platt S, Amos A: Equity impact of interventions and policies to reduce smoking in youth: systematic review. Tobacco control 2014:tobaccocontrol-2013-051451.

Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Chiodo D, Hughes R, Ellis W. Observations of adolescent peer resistance skills following a classroom-based healthy relationship program: a post-intervention comparison. Prev Sci. 2012;13(2):196–205.

Magnée T, Burdorf A, Brug J, Kremers SP, Oenema A, van Assema P, Ezendam NP, van Genugten L, Hendriksen IJ, Hopman-Rock M. Equity-specific effects of 26 Dutch obesity-related lifestyle interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(6):e61–70.

Lien N, Haerens L, Te Velde SJ, Mercken L, Klepp K-I, Moore L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Faggiano F, van Lenthe FJ. Exploring subgroup effects by socioeconomic position of three effective school-based dietary interventions: the European TEENAGE project. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(3):493–502.

Petticrew M, Tugwell P, Kristjansson E, Oliver S, Ueffing E, Welch V. Damned if you do, damned if you don9t: subgroup analysis and equity. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2011:jech;2010:121095.

Oxman AD. Subgroup analyses. In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2012.

Mercken L, Moore L, Crone M, De Vries H, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lien N, Fagiano F, Vitória P, Van Lenthe F. The effectiveness of school-based smoking prevention interventions among low-and high-SES European teenagers. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(3):459–69.

Pförtner T-K, Hublet A, Schnohr CW, Rathmann K, Moor I, de Looze M, Baška T, Molcho M, Kannas L, Kunst AE. Socioeconomic inequalities in the impact of tobacco control policies on adolescent smoking. A multilevel study in 29 European countries. Addict Behav. 2016;53:58–66.

Moore GF, Tapper K, Moore L, Murphy S. Cognitive, behavioral, and social factors are associated with bias in dietary questionnaire self-reports by schoolchildren aged 9 to 11 years. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(11):1865–73.

Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C, Zambon A. The family affluence scale as a measure of National Wealth: validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Soc Indic Res. 2006;78(3):473–87.

Bodin M, Leifman H. A randomized effectiveness trial of an adult-to-youth mentoring program in Sweden. Addict Res Theory. 2011;19(5):438–47.

Brown EC, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Adolescent substance use outcomes in the raising healthy children project: a two-part latent growth curve analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):699.

Connell AM, Dishion TJ, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An adaptive approach to family intervention: linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(4):568.

D’Amico EJ, Fromme K. Brief prevention for adolescent risk-taking behavior. Addiction. 2002;97(5):563–74.

DeGarmo DS, Eddy JM, Reid JB, Fetrow RA. Evaluating mediators of the impact of the linking the interests of families and teachers (LIFT) multimodal preventive intervention on substance use initiation and growth across adolescence. Prev Sci. 2009;10(3):208–20.

Haggerty KP, Skinner ML, MacKenzie EP, Catalano RF. A randomized trial of parents who care: effects on key outcomes at 24-month follow-up. Prev Sci. 2007;8(4):249–60.

Ialongo NS, Werthamer L, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Wang S, Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(5):599–641.

Kellam SG, Brown CH, Poduska JM, Ialongo NS, Wang W, Toyinbo P, Petras H, Ford C, Windham A, Wilcox HC. Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:S5–S28.

O'Neill JM, Clark JK, Jones JA. Promoting mental health and preventing substance abuse and violence in elementary students: a randomized control study of the Michigan model for health. J Sch Health. 2011;81(6):320–30.

Piper DL, Moberg DP, King MJ. The healthy for life project: behavioral outcomes. J Prim Prev. 2000;21(1):47–73.

Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(4):627.

Walker Z, Townsend J, Oakley L, Donovan C, Smith H, Hurst Z, Bell J, Marshall S. Health promotion for adolescents in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7363):524.

Bernstein J, Heeren T, Edward E, Dorfman D, Bliss C, Winter M, Bernstein E. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(8):890–902.

Berry V, Little M, Axford N, Cusick GR. An evaluation of youth at Risk's coaching for communities programme. Howard J Crime Justice. 2009;48(1):60–75.

Bond L, Glover S, Godfrey C, Butler H, Patton GC. Building capacity for system-level change in schools: lessons from the gatehouse project. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(3):368–83.

Brody GH, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Yu T, Molgaard VK, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. Family-centered program deters substance use, conduct problems, and depressive symptoms in black adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):108–15.

Bush PJ, Zuckerman AE, Taggart VS, Theiss PK, Peleg EO, Smith SA. Cardiovascular risk factor prevention in black school children: the know your body evaluation project. Health Educ Q. 1989;16(2):215–27.

Catalano RF, Gainey RR, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Johnson NO. An experimental intervention with families of substance abusers: one-year follow-up of the focus on families project. Addiction. 1999;94(2):241–54.

Clark HK, Ringwalt CL, Hanley S, Shamblen SR, Flewelling RL, Hano MC. Project SUCCESS' effects on the substance use of alternative high school students. Addict Behav. 2010;35(3):209–17.

Conduct Problems Prevention Research G. Trajectories of risk for early sexual activity and early substance use in the fast track prevention program. Prev Sci. 2014;15(Suppl 1):S33–46.

Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, Shope JT, Bingham CR, Blow FC, Walton MA. Brief motivational interviewing intervention for peer violence and alcohol use in teens: one-year follow-up. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1083–90.

Elder JP, Litrownik AJ, Slymen DJ, Campbell NR, Parra-Medina D, Choe S, Lee V, Ayala GX. Tobacco and alcohol use–prevention program for Hispanic migrant adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):269–75.

Fang L, Schinke SP, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among early Asian-American adolescent girls: initial evaluation of a web-based, mother-daughter program. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(5):529–32.

Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):377–84.

Freudenberg N, Ramaswamy M, Daniels J, Crum M, Ompad DC, Vlahov D. Reducing drug use, human immunodeficiency virus risk, and recidivism among young men leaving jail: evaluation of the REAL MEN re-entry program. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(5):448–55.

Furr-Holden CDM, Ialongo NS, Anthony JC, Petras H, Kellam SG. Developmentally inspired drug prevention: middle school outcomes in a school-based randomized prevention trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(2):149–58.

Gersick KE, Grady K, Snow DL. Social-cognitive skill development with sixth graders and its initial impact on substance use. J Drug Educ. 1988;18(1):55–70.

Gilchrist LD, Schinke SP, Trimble JE, Cvetkovich GT. Skills enhancement to prevent substance abuse among American Indian adolescents. Int J Addict. 1987;22(9):869–79.

Gonzales NA, Wong JJ, Toomey RB, Millsap R, Dumka LE, Mauricio AM. School engagement mediates long-term prevention effects for Mexican American adolescents. Prev Sci. 2014;15(6):929–39.

Griffin JP Jr., , Holliday RC, Frazier E, Braithwaite RL: The BRAVE (building resiliency and vocational excellence) program: evaluation findings for a career-oriented substance abuse and violence preventive intervention. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009, 20(3):798–816.

Hallfors D, Cho H, Sanchez V, Khatapoush S, Kim HM, Bauer D. Efficacy vs effectiveness trial results of an indicated “model” substance abuse program: implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2254–9.

Horan JJ, Williams JM. Longitudinal study of assertion training as a drug abuse prevention strategy. Am Educ Res J. 1982;19(3):341–51.

Kim HK, Leve LD. Substance use and delinquency among middle school girls in foster care: a three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(6):740–50.

Kitzman HJ, Olds DL, Cole RE, Hanks CA, Anson EA, Arcoleo KJ, Luckey DW, Knudtson MD, Henderson CR, Holmberg JR. Enduring effects of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses on children: follow-up of a randomized trial among children at age 12 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(5):412–8.

Komro KA, Perry CL, Veblen-Mortenson S, Farbakhsh K, Toomey TL, Stigler MH, Jones-Webb R, Kugler KC, Pasch KE, Williams CL. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a multi-component alcohol use preventive intervention for urban youth: project northland Chicago. Addiction. 2008;103(4):606–18.

Lewis KM, DuBois DL, Bavarian N, Acock A, Silverthorn N, Day J, Ji P, Vuchinich S, Flay BR. Effects of positive action on the emotional health of urban youth: a cluster-randomized trial. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(6):706–11.

Li X, Stanton B, Galbraith J, Burns J, Cottrell L, Pack R. Parental monitoring intervention: practice makes perfect. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(5):364.

Lochman JE, Wells KC. Effectiveness of the coping power program and of classroom intervention with aggressive children: outcomes at a 1-year follow-up. Behav Ther. 2003;34(4):493–515.

Lochman JE, Wells KC. The coping power program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: outcome effects at the 1-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(4):571–8.

LoSciuto L, Hilbert SM, Fox MM, Porcellini L, Lanphear A. A two-year evaluation of the wood rock youth development project. J Early Adolesc. 2016;19(4):488–507.

Marsden J, Stillwell G, Barlow H, Boys A, Taylor C, Hunt N, Farrell M. An evaluation of a brief motivational intervention among young ecstasy and cocaine users: no effect on substance and alcohol use outcomes. Addiction. 2006;101(7):1014–26.

Murry VM, McNair LD, Myers SS, Y-f C, Brody GH. Intervention induced changes in perceptions of parenting and risk opportunities among rural African American. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23(2):422–36.

McCambridge J, Hunt C, Jenkins RJ, Strang J. Cluster randomised trial of the effectiveness of motivational interviewing for universal prevention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114(2–3):177–84.

Milburn NG, Iribarren FJ, Rice E, Lightfoot M, Solorio R, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Desmond K, Lee A, Alexander K, Maresca K, et al. A family intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior, substance use, and delinquency among newly homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(4):358–64.

Minnis AM, vanDommelen-Gonzalez E, Luecke E, Dow W, Bautista-Arredondo S, Padian NS. Yo Puedo--a conditional cash transfer and life skills intervention to promote adolescent sexual health: results of a randomized feasibility study in San Francisco. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):85–92.

Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Myers M, Woolard R, Lewander W. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):989.

Morris P, Michalopoulos C. Findings from the self-sufficiency project: effects on children and adolescents of a program that increased employment and income. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24(2):201–39.

Newton NC, Andrews G, Teesson M, Vogl LE. Delivering prevention for alcohol and cannabis using the internet: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med. 2009;48(6):579–84.

Nirenberg T, Baird J, Longabaugh R, Mello MJ. Motivational counseling reduces future police charges in court referred youth. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;53:89–99.

Nores M, Belfield CR, Barnett WS, Schweinhart L. Updating the economic impacts of the high/scope Perry preschool program. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2016;27(3):245–61.

Palinkas LA, Atkins CJ, Miller C, Ferreira D. Social skills training for drug prevention in high-risk female adolescents. Prev Med. 1996;25(6):692–701.

Pantin H, Prado G, Lopez B, Huang S, Tapia MI, Schwartz SJ, Sabillon E, Brown CH, Branchini J. A randomized controlled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(9):987–95.

Redding CA, Prochaska JO, Armstrong K, Rossi JS, Hoeppner BB, Sun X, Kobayashi H, Yin HQ, Coviello D, Evers K, et al. Randomized trial outcomes of a TTM-tailored condom use and smoking intervention in urban adolescent females. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(1):162–78.

Sanchez V, Steckler A, Nitirat P, Hallfors D, Cho H, Brodish P. Fidelity of implementation in a treatment effectiveness trial of reconnecting youth. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(1):95–107.

Schwinn TM, Schinke SP, Di Noia J. Preventing drug abuse among adolescent girls: outcome data from an internet-based intervention. Prev Sci. 2010;11(1):24–32.

Shetgiri R, Kataoka S, Lin H, Flores G. A randomized, controlled trial of a school-based intervention to reduce violence and substance use in predominantly Latino high school students. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(9–10):932–40.

Sussman S, Dent CW, Stacy AW, Craig S. One-year outcomes of project towards no drug abuse. Prev Med. 1998;27(4):632–42.

Tierney JP: Making a difference. An Impact Study of Big Brothers/Big Sisters 1995.

Vitaro F, Dobkin PL, Tremblay RE. Programme de prévention des toxicomanies en milieu scolaire. Int J Psychol. 1994;29(4):431–52.

Wagner EF, Hospital MM, Graziano JN, Morris SL, Gil AG. A randomized controlled trial of guided self-change with minority adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(6):1128–39.

Bauman KE, Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Hicks K, Pemberton M. Family matters: a family-directed program designed to prevent adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Health Promot Pract. 2001;2(1):81–96.

Beets MW, Flay BR, Vuchinich S, Snyder FJ, Acock A, Li KK, Burns K, Washburn IJ, Durlak J. Use of a social and character development program to prevent substance use, violent behaviors, and sexual activity among elementary-school students in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1438–45.

McClain DB, Wolchik SA, Winslow E, Tein J-Y, Sandler IN, Millsap RE. Developmental cascade effects of the new beginnings program on adolescent adaptation outcomes. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(4):771–84.

Clayton RR, Cattarello AM, Johnstone BM. The effectiveness of drug abuse resistance education (project DARE): 5-year follow-up results. Prev Med. 1996;25(3):307–18.

Dent CW, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Project towards no drug abuse: generalizability to a general high school sample. Prev Med. 2001;32(6):514–20.

Brady B. Big brothers big sisters of Ireland: evaluation study. In: Report One: Randomised Control Trial and Implementation Report; 2011.

Donaldson SI, Graham JW, Hansen WB. Testing the generalizability of intervening mechanism theories: understanding the effects of adolescent drug use prevention interventions. J Behav Med. 1994;17(2):195–216.

Eisen M, Zellman GL, Murray DM. Evaluating the lions–quest “skills for adolescence” drug education program. Addict Behav. 2003;28(5):883–97.

Fearnow-Kenney MD, Wyrick DL, Jackson-Newsom J, Wyrick CH, Hansen WB. Initial indicators of effectiveness for a high school drug prevention program. Am J Health Educ. 2003;34(2):66–71.

Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Nichols TR. Effects of a school-based drug abuse prevention program for adolescents on HIV risk behavior in young adulthood. Prev Sci. 2006;7(1):103–12.

Hansen WB, Graham JW. Preventing alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among adolescents: peer pressure resistance training versus establishing conservative norms. Prev Med. 1991;20(3):414–30.

Li KK, Washburn I, DuBois DL, Vuchinich S, Ji P, Brechling V, Day J, Beets MW, Acock AC, Berbaum M, et al. Effects of the positive action programme on problem behaviours in elementary school students: a matched-pair randomised control trial in Chicago. Psychol Health. 2011;26(2):187–204.

McCambridge J, Strang J. Deterioration over time in effect of motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and related risk among young people. Addiction. 2005;100(4):470–8.

McCambridge J, Slym RL, Strang J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing compared with drug information and advice for early intervention among young cannabis users. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1809–18.

McNeal RB Jr, Hansen WB, Harrington NG, Giles SM. How all stars works: an examination of program effects on mediating variables. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):165–78.

Melnyk BM, Jacobson D, Kelly S, Belyea M, Shaibi G, Small L, O'Haver J, Marsiglia FF. Promoting healthy lifestyles in high school adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):407–15.

Moskowitz JM, Malvin JH, Schaeffer GA, Schaps E. An experimental evaluation of a drug education course. J Drug Educ. 1984;14(1):9–22.

Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, Perry CL, Osganian SK, Kelder S, Webber LS, Elder JP, Montgomery D, Feldman HA. Three-year maintenance of improved diet and physical activity: the CATCH cohort. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(7):695–704.

Olds D, Henderson CR Jr, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Pettitt L, Sidora K, Morris P, Powers J. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children's criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(14):1238–44.

Palmer RF, Graham JW, White EL, Hansen WB. Applying multilevel analytic strategies in adolescent substance use prevention research. Prev Med. 1998;27(3):328–36.

Patton GC, Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Butler H, Glover S, Catalano R, Bowes G. Promoting social inclusion in schools: a group-randomized trial of effects on student health risk behavior and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1582–7.

Pentz M, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, et al. A multicommunity trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse: effects on drug use prevalence. JAMA. 1989;261(22):3259–66.

Perry CL, Komro KA, Veblen-Mortenson S, Bosma LM, Farbakhsh K, Munson KA, Stigler MH, Lytle LA. A randomized controlled trial of the middle and junior high school DARE and DARE plus programs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(2):178–84.

Roberts C, Williams R, Kane R, Pintabona Y, Cross D, Zubrick S, Silburn S. Impact of a mental health promotion program on substance use in young adolescents. Adv Ment Health. 2011;10(1):72–82.

Saraf DS, Gupta SK, Pandav CS, Nongkinrih B, Kapoor SK, Pradhan SK, Krishnan A. Effectiveness of a school based intervention for prevention of non-communicable diseases in middle school children of rural North India: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82(4):354–62.

Schaps E, Moskowitz JM, Condon JW, Malvin JH. Process and outcome evaluation of a drug education course. J Drug Educ. 1982;12(4):353–64.

Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KC. Computer-delivered, parent-involvement intervention to prevent substance use among adolescent girls. Prev Med. 2009;49(5):429–35.

Shek DT, Yu L. Prevention of adolescent problem behavior: longitudinal impact of the project P.a.T.H.S. in Hong Kong. Scientific World J. 2011;11:546–67.

Simons-Morton B, Haynie D, Saylor K, Crump AD, Chen R. The effects of the going places program on early adolescent substance use and antisocial behavior. Prev Sci. 2005;6(3):187–97.

Sloboda Z, Pyakuryal A, Stephens PC, Teasdale B, Forrest D, Stephens RC, Grey SF. Reports of substance abuse prevention programming available in schools. Prev Sci. 2008;9(4):276–87.

Sun W, Skara S, Sun P, Dent CW, Sussman S. Project towards no drug abuse: long-term substance use outcomes evaluation. Prev Med. 2006;42(3):188–92.

Sun P, Sussman S, Dent CW, Rohrbach LA. One-year follow-up evaluation of project towards no drug abuse (TND-4). Prev Med. 2008;47(4):438–42.

Taylor BJ, Graham JW, Cumsille P, Hansen WB. Modeling prevention program effects on growth in substance use: analysis of five years of data from the adolescent alcohol prevention trial. Prev Sci. 2000;1(4):183–97.

Valente TW, Ritt-Olson A, Stacy A, Unger JB, Okamoto J, Sussman S. Peer acceleration: effects of a social network tailored substance abuse prevention program among high-risk adolescents. Addiction. 2007;102(11):1804–15.

Walter HJ, Hofman A, Connelly PA, Barrett LT, Kost KL. Coronary heart disease prevention in childhood: one-year results of a randomized intervention study. Am J Prev Med. 1986;2(4):239–45.

Acknowledgements

This study is sponsored by the University of Bristol.

Funding

LT is a PhD student funded by the Medical Research Council within the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Public Health Interventions (DECIPHer). The work was undertaken with the support of The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Joint funding (MR/KO232331/1) from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

GJM is funded by an NIHR post-doctoral fellowship award (PDF-2013-06-026). This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (Post-Doctoral Fellowship, PDF-2013-06-026). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LT, RC, MH developed the research project. LT conducted the screening of the papers and GJM provided screening support and made available information already gleaned from the Cochrane systematic review. GD, AL, PM and DW provided additional quantitative data such as tables and interaction tests. LT and DC conducted the data analyses. LT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the manuscript before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tinner, L., Caldwell, D., Hickman, M. et al. Examining subgroup effects by socioeconomic status of public health interventions targeting multiple risk behaviour in adolescence. BMC Public Health 18, 1180 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6042-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6042-0