Abstract

Background

Previous studies have provided inconsistent findings on smoking among migrants, and very limited data exist on their second-hand smoke exposure. This study aims to investigate internal migrants’ smoking prevalence, second-hand smoke exposure among non-smokers, and knowledge of the health hazards of smoking in 12 major migrant provinces in China in 2013.

Methods

Data from the 2013 Migrant Dynamics Monitoring Survey in China published by the National Commission of Health and Family Planning was used in this study. Descriptive analysis, Chi-square analysis, and sex-stratified multivariate logistic regression analysis were used to explore the determinants of current smoking and second-hand smoke exposure.

Results

Among 7200 migrants, 34.1% (55% male, 4% female) were current smokers. For males, factors associated with current smoking were education year (aOR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93–0.98), duration of stay (aOR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.03) and occupation (aOR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.03–1.53). For females, household registration status (aOR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.04–2.80) was the most important factor associated with current smoking. Sixty five percent of non-smokers were exposed to second-hand smoke. Factors associated with exposure to second-hand smoke were duration of stay (aOR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.02), divorced/widowed marital status (aOR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.25–0.91), occupation (aOR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.05–1.58) and the nature of employer (aOR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.60–0.97). About 95% of participants were aware that lung cancer is one of the hazards of smoking. Non-current smokers had a better knowledge of fertility reduction and accelerated aging as hazards of smoking than current smokers (p < 0.01). Knowledge of the impact of smoking on cardiovascular diseases was relatively low compared with knowledge of other smoking-related hazards (26.1–44.3%).

Conclusions

Current smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke among internal migrants in China is high. Socio-demographic characteristics and migration status were strongly associated with current smoking and second-hand smoke exposure. We recommend specifically targeted tobacco control interventions to help to address these risk factors, such as focusing on divorced/widowed women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

China is the world’s largest consumer of tobacco products and contributes substantially to the global burden of smoking-related diseases [1]. According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) conducted in 2010, 28.1% of adults in China were current smokers, with 72.4% of non-current smoking adults were exposed to second-hand smoke (SHS) in a typical week [2].

Internal migrants are defined as, ‘individuals who move within the borders of a country, usually measured across regional, district, or municipal boundaries, resulting in a change of usual place of residence’ [3]. The word ‘internal’ is used to differentiate this population from the cross-border migrants (generally called international migrants):‘individuals who remain outside their usual country of residence for at least one year’ [4]. China has a unique household registration system which functions as an ‘internal passport system’ to restrict Chinese citizens’ access to public services to their place of birth. Few can obtain local residency rights when they move away from their place of birth. This creates a two-system category of internal migrants: household registered and non-household registered, with the vast majority of internal migrants belonging to the latter.

In 2012 there were 236 million, or one in six, internal migrants in China [5], most of whom moved from less to more developed provinces and from villages to cities and towns. Most migrants are poorly educated, young and middle-aged men who take up low paying and labour-intensive jobs in the informal sector [6]. In addition, they have limited access to health services. Several studies have shown that migrants are at higher risk of communicable and non-communicable diseases, occupation-related conditions, sexual health problems, and psychological problems [7,8,9]. The stress induced by migration, and poor living and working conditions, are likely to increase the risk of substance abuse in this population [10].

Results of previous studies on smoking among internal Chinese migrants have been inconsistent: whilst some report a higher smoking prevalence among internal migrants than among urban residents [11, 12] others show the converse [13,14,15]. The same inconsistency is found in studies comparing international migrants to natives [16, 17]. A systematic review conducted by Liu et al. showed that smoking prevalence among male migrants was lower than the general population (pooled estimate 46.7% versus 52.9%) whilst smoking prevalence among female migrants was higher than the general population (5.3% versus 2.4%) [18]. However, a national study by Ji et al., not included in this review [14], reported a lower smoking rate among migrants than the general population. The foregoing uncertainty around smoking in migrant populations is justification for a more thorough investigation of the subject.

There is a paucity of data from China on SHS exposure. One study reported that 43.6% of female internal migrants in China were exposed to SHS [19]. With regards to knowledge of the effects of smoking on health, a study on rural-to-urban migrant women in Beijing found that the proportion of migrant women who believed smoking increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, lung cancer and hepatitis was 61, 92, and 57% respectively [20]. Our literature search found no evidence that knowledge of other health hazards of smoking has been explored in this population.

This study aims to investigate smoking prevalence, exposure to SHS, and knowledge of the hazards of smoking and their determinants among internal migrants in 12 major migrant provinces in China in 2013.

Methods

Data sources

The current study is a secondary data analysis. We obtained data from the 2013 Migrant Dynamics Monitoring Survey in China. The survey was published by the National Population and Family Planning Commission and focused on basic public health services, health, and family planning for the Chinese migrant population. Respondents to the survey included men and women aged 15–59 years as of August 2013 who had been residing in a locality for six months or longer, with a non-local district (province, municipality, county) household registration. The survey used the annual national migrant reported data in 2012 as the basic information and adopted a four-stage sampling method.

In stage one, 12 of the 31 provinces of China were selected. These provinces included six that receive the highest number of internal migrants: Guangdong, Zhejiang, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Fujian [21]. The others were Tianjin, Liaoning and Shandong (all eastern), Henan (central), and Chongqing and Sichuan (both western). In stage two, eight sub-districts in each province were randomly selected by PPS method. The sub-district sampling frame was obtained from the same national survey on migrant populations conducted by the National Population and Family Planning Commission in 2012 [22]. In stage three, a quota-sampling procedure was applied to recruit the participants. Work units were selected according to location, level of industrialization and topography. In stage four, eligible participants were selected at the sampling units. The number of participants in each sampling unit was limited to 15. Data collectors were drawn from the host communities. The enumerators contacted respondents by phone to explain the purpose of the study and request an appointment. Respondents who agreed to be interviewed were then visited and formal informed consent was obtained for interview. No identification information on survey participants was included in this study. The ethics approval was exempted by Peking University Institution Review Board. All participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the study, and provided verbal consent [23].

Measures

We measured three outcomes: current smoking prevalence, SHS exposure, and knowledge of the hazards of smoking. The survey used the World Health Organization (WHO) global standard for smoking [24], where those responding “Yes” to “Do you currently smoke tobacco?” were considered current smokers. Nonsmokers were asked “How many days per week are you exposed to second-hand smoke usually?” Those who answered “none” were categorized as non-exposed to SHS and all others (“1-3 days per week”, “4-6 days per week” and “almost every day”) were categorized as exposed to SHS. All participants answered multiple choice questions on their knowledge of hazards of smoking: “Which of the following diseases do you think smoking can lead to?” Options included lung cancer, fertility reduction, accelerated aging, cardiovascular diseases, heart disease, and stroke. Participants answering “Yes” to any disease were deemed to have correct knowledge of the hazards of smoking.

Independent variables included basic demographic features (sex, age, marriage, years of education, and household registration type [agricultural and nonagricultural]), migration characteristics (migration type [trans-provincial, trans-municipal and trans-county], duration of stay [years], employment characteristics (employment status [yes/no], nature of employment [within the system,Footnote 1 outside the system,Footnote 2 agricultural, unemployed and others], and working hours per week.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS13©. The sample was described using frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Chi-squared tests were performed to examine the associations between smoking prevalence and socio-demographic characteristics, migration history and working conditions. Differences in the knowledge of the hazards of smoking between current and non-current smokers were also tested with Chi-squared tests. Multivariate logistic regression was applied to identify independent variables associated with current cigarette smoking and with SHS, from which adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. Smoking-related factors, including socio-demographic characteristics, employment and migration history were cross-tabulated with smoking status and SHS status. A p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Due to the large sex differences in smoking, the regression model was sex-stratified.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The survey sampled 7208 individuals and achieved a response rate 99.9%. General characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Respondents ranged from 15 to 59 years of age, with a mean (SD) age of 33.3 ± 0.1. More men (59.9%) than women (40.1%) participated in the study (Table 1). The majority of respondents were married (82.5%) with agricultural household registration status (79.8%). The average number of years of education was 10.1 ± 0.4 years. More than 56% of participants were employed. The majority of migrants worked as business and service personnel (63.9%) and outside the system (81.6%). More than 60% of participants’ migrations were between-provinces.

Prevalence of smoking

Among the 7200 participants, 34.1% (95% CI: 33.0–35.2%) were current smokers; this is broken down by socio-demographic characteristics in Table 2. Current smoking was significantly higher among men than among women (54.5% vs. 3.7%, p < 0.001).

For men, the prevalence of current smoking was significantly higher among older respondents, respondents with less educational attainment, shorter duration of stay, working 40–70 h per week, with agricultural household registration status, with unemployment, and trans-county migration type. There were also some differences by occupational type and employer nature.

Women only shared one socio-demographic pattern as men: higher prevalence of current smoking among older respondents. Differences to men include a higher prevalence of current smoking among divorcees, and non-agricultural household registration status. Other socio-demographic characteristics did not significantly differ among women.

Prevalence of SHS exposure

In total, 65.1% of non-smokers were exposed to SHS (95% CI: 64.0–66.2%) and there was no significant differences between males and females (65.5% vs. 64.9%, p = 0.666). The prevalence of SHS exposure among non-smokers was higher in those who worked 40–70 h per week, had shorter duration of stay, those whose employment was agricultural, unemployed or other, those with an employer within the system, and those who had migrated between counties.

Knowledge of hazards of smoking

Migrants’ knowledge of hazards of smoking are shown in Table 3. About 95% of all participants were aware that lung cancer is one of the hazards of smoking and there was no difference between current smokers (94.7%) and non-smokers (95.0%). Nevertheless, more non-smokers had knowledge that fertility reduction is a hazard of smoking than current smokers (56.0% vs. 49.4%, p < 0.001). More non-smokers also had knowledge that accelerated aging is a hazard of smoking than current smokers (56.0% vs. 49.4%, p < 0.001). All participants’ knowledge of cardiovascular diseases (43.8%), heart disease (35.0%) and stroke (26.2%) as hazards of smoking were comparatively low compared with their knowledge of lung cancer (94.8%), fertility reduction (54.4%) and accelerated aging (53.8%).

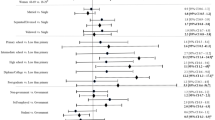

Multivariate analyses

Sex-stratified multivariate logistic regression results are shown in Table 4. In the male model, age (aOR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03), years of education (aOR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93–0.98), and duration of stay (aOR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.97–1.00) were factors significantly associated with current smoking. Other factors included the type of occupation (business and service personnel (aOR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.03–1.53); production, transportation and facility operation personnel (aOR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.23–1.88)) and trans-county migration (aOR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.05–1.66). Employment status, working hours per week, household registration status, and the nature of employment were not associated with current smoking among males.

In the female model, age (aOR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.00–1.06), household registration status (aOR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.04–2.80) and marital status (aOR = 3.20, 95% CI: 1.00–10.25) were the factors significantly associated with smoking. Employment status, though significantly associated with current smoking on the bivariate analysis, was no longer significant on the multivariate analysis.

The multivariate logistic regression results of determinants of SHS exposure among non-smokers are shown in Table 4. Duration of stay (aOR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98–1.00), marital status (aOR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.25–0.91) and trans-county migration (aOR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.20–1.98) were associated with SHS exposure. Other factors significant in the bivariate analysis, including working hours per week and employment status, were no longer significant in the logistic regression model.

Discussion

This is the first large-scale study to investigate SHS exposure and knowledge of smoking hazards among internal migrants in China. The large difference in current smoking prevalence by sex is similar to previous studies [1, 13, 14, 25]. For male migrants, the prevalence of current smoking in this study (54.4%) was slightly higher than that for the general male population (52.9%) and for urban male residents (49.2%), but lower than for rural male residents (56.1%), as reported in the 2010 GATS [2]. For female migrants, the prevalence of current smoking in this study (3.7%) was higher than females living in both rural (2.2%) and urban (2.6%) settings, as reported in the 2010 GATS [2]. This study’s prevalence estimates are higher than nearly all other national and subnational estimates of smoking prevalence in China [1, 13, 14, 25] except one [26]. These variations in reported rates of smoking may be attributed to the different study locations, sampling frames and demographic characteristics of the populations enrolled.

Studies show that men may face increased restrictions on tobacco use at work or increased social pressure not to smoke, resulting in reduced smoking after migration, whilst women may have enhanced independence, less restrictive social norms and higher incomes, resulting in higher smoking rates after migration [14, 27]. Three previous studies [1, 13, 26] supported this trend while another two reported discrepancies [14, 25].

Lack of education can limit awareness of the hazards of smoking and can account for the higher prevalence of smoking among less educated persons [28], as was found in our and in other studies [14, 29]. Longer duration of stay may indicate better inclusion of migrants in their new areas and less social stress, and therefore less tobacco use, as was shown in our results, although the evidence on this is mixed [1, 14, 15]. Evidence for smoking prevalence among migrants by occupation also continues to be highly inconsistent [1, 15], and our analysis could add further insight to this debate. We found that male migrants who migrated between counties had a higher prevalence of smoking than those who migrated between provinces and between municipalities; no previous study examined this association in this population.

For female migrants, the logistic regression model showed non-agricultural female migrants had increased odds of current smoking than agricultural female migrants. In the study by Ji et al., however, there was no significant association between household registration status and smoking in female migrants [14]. Our model showed that divorced/widowed females had 3.20 times the odds of current smoking compared to never married and married females, while in the study by Ji et al., again no such difference was found [14].

In this study, the prevalence of SHS exposure among non-smokers was 65.1%, which was lower than the national prevalence reported in the 2010 GATS [24] (72.4%) but similar to a study by Huang et al. (68.7%) [30]. Our determinants of SHS exposure are somewhat concordant with those of Huang et al., in that they too found occupation to be a significant determinant of SHS exposure, however they also found determinants that we did not, such as age and education [30].

Our results show that migrants’ knowledge of the hazard of ‘smoking-associated lung cancer’ was far greater than their knowledge of other hazards. This finding is consistent with a study by Finch et al. on rural-to-urban migrant women in Beijing [20], and a further national study [31]. Both studies reported that non-current smokers’ knowledge of smoking-associated accelerated aging was significantly higher than current smokers’ knowledge, indicating that health education on smoking hazards might help to control and reduce smoking prevalence.

To our knowledge, ours is only the second study that has analyzed a large-scale migrant sample for smoking prevalence and its determinants. Our results provide overall levels of migrant smoking prevalence and the influences of migration-related factors on smoking. This is also the first large-scale study to investigate SHS exposure among non-smokers and knowledge of smoking hazards among internal migrants. These results provide a knowledge base for developing or improving tobacco control interventions among migrants, such as focusing on divorced/widowed women.

This study is not without limitations, however. First, it is a cross-sectional study so we cannot draw conclusions regarding causality. Secondly, it used typical sampling methods rather than random sampling so the point estimates and associated variance estimates might be biased. Thirdly, as the data used were not obtained from a smoking-specific survey, the responses were limited smoking status, exposure to SHS and knowledge of the hazards of smoking. Lastly, weighting was not performed prior to the analysis, so there is a chance that the probability of selection of respondents was not equal.

Conclusion

The prevalence of current smoking and SHS exposure among internal migrants were high. Risk factors associated with current smoking among male migrants include age, years of education, duration of stay in a location after migrating there, occupational type and migration type. Among female migrants risk factors include age, household-registration status and marital status. Factors associated with SHS exposure among non-smokers include duration of stay, marital status, occupation type, nature of employment and migration type.

Our findings suggest the need for specifically targeted tobacco control interventions for the rapidly growing and changing internal migrant population. We recommend further tobacco control measures to address the identified risk factors. Due to the limited number of studies and the inconsistencies between studies, further specialized research into the smoking behaviors of internal migrants in China is required in order to determine whether similar factors may contribute to smoking behavior nationwide.

Notes

Outside the system: refers to those who are not within the formal sector but are not unemployed and are not working in agriculture.

Within the system: refers to civil servants system and those employed by public institutions and state-owned enterprises.

Abbreviations

- SHS:

-

Second-hand smoke

- GATS:

-

Global Adult Tobacco Survey

References

Liu Y, Song H, Wang T, Wang T, Yang H, Gong J, Shen Y, Dai W, Zhou J, Zhu S, et al. Determinants of tobacco smoking among rural-to-urban migrant workers: a cross-sectional survey in Shanghai. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:131.

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) China 2010 Country Report. China Sanxia Press: Beijing; 2011. p. 10–22.

United Nations Development Programme. Human development report 2009: overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development. United Nations Development Programme: New York; 2009.

United Nations Population Division. International migrant stock: the 2008 revision. United Nations: Geneva; 2009.

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. 2010 Population Census. China Statistics Press: Beijing; 2010.

Zheng YT, Chang C, Ji Y, Yuan YF, Jiang Y, Li Z. The status quo and subjective need for health knowledge among internal migrants. Chin J Health Educ. 2017;33(6):3.

Hu LX, Chen YY. Migrants’ public health situation. Mod Prev Med. 2007;34(1):96–8.

Ye XJ, Shi WX, Li L. Health status of migrant workers in cities and policy suggestions. Chin J Hosp Adm. 2004;20(9):562–6.

Huang JH. Hygienic condition and disease prevention of shifting population. Chin Rural Health Serv Adm. 2007;27(6):460–1.

Chen X, Stanton B, Li X, Fang X, Lin D. Substance use among rural-to-urban migrants in China: a moderation effect model analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(1):105–24.

Cui X, Rockett IR, Yang T, Cao R. Work stress, life stress, and smoking among rural-urban migrant workers in China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:979.

Wan X, Shin SS, Wang Q, Raymond HF, Liu H, Ding D, Yang G, Novotny TE. Smoking among young rural to urban migrant women in China: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23028.

Hesketh T, Lu L, Jun YX, Mei WH. Smoking, cessation and expenditure in low income Chinese: cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:29.

Ji Y, Liu S, Zhao X, Jiang Y, Zeng Q, Chang C. Smoking and its determinants in Chinese internal migrants: nationally representative cross-sectional data analyses. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(8):1719–26.

Yang T, Wu J, Rockett IR, Abdullah AS, Beard J, Ye J. Smoking patterns among Chinese rural-urban migrant workers. Public Health. 2009;123(11):743–9.

United States. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among Chinese, Vietnamese, and Hispanics--California, 1989–1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(20):362–67.

Niaura R, Shadel WG, Britt DM, Abrams DB. Response to social stress, urge to smoke, and smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2002;27(2):241–50.

Liu Y, Gao J, Shou J, Xia H, Shen Y, Zhu S, Pan Z. The prevalence of cigarette smoking among rural-to-urban migrants in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(2):206–15.

Gong X, Luo X, Ling L. Prevalence and associated factors of secondhand smoke exposure among internal Chinese migrant women of reproductive age: evidence from China’s labor-force dynamic survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(4):371.

Finch K, Novotny TE, Ma S, Qin D, Xia W, Xin G. Smoking knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among rural-to-urban migrant women in Beijing, China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(3):342–53.

planning Ncohaf. Report on China’s migrant population development. In: Basic public Services for Migrant Population. 2014 edn. Beijing: National commission of health and family planning; 2014. p. 71.

planning Ncohaf. Special investigation plan on basic public services on health and family planning among migrant population 2013. Edited by planning Ncohaf. Beijing: National commission of health and family planning; 2013: 8.

National Commission of Health and Family Planning. Handbook of dynamic monitoring on migrants in China(2013). Beijing: National commission of health and family planning; 2013.

Group GATSC. Tobacco questions for surveys: a subset of key questions from the global adult tobacco survey (GATS). In: 2nd Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. p. 14–7.

Mou J, Fellmeth G, Griffiths S, Dawes M, Cheng J. Tobacco smoking among migrant factory workers in Shenzhen, China. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):69–76.

Chen X, Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D, Cole M, Liu H, Yang H. Cigarette smoking among rural-to-urban migrants in Beijing, China. Prev Med. 2004;39(4):666–73.

Gorman BK, Lariscy JT, Kaushik C. Gender, acculturation, and smoking behavior among U.S. Asian and Latino immigrants. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:110–8.

Zhang R, Cao Q, Lu Y. The analysis of cigarette smoking behaviors and its influencing factors among chinese urban and rural residents. Acta Univ Med Nanjing (Nat Sci). 2014;34(01):84–9.

Li Q, Hsia J, Yang G. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2469–70.

Huang ZJ, Wang LM, Zhang M, et al. Tobacco control floating population prevalence of current smoking smoking cessation exposed to secondhand smoke. Chin J Epidemiol. 2014;11(35):1192–7.

Yang J, Hammond D, Driezen P, Fong GT, Jiang Y. Health knowledge and perception of risks among Chinese smokers and non-smokers: findings from the wave 1 ITC China survey. Tob Control. 2010;19(Suppl 2):i18–23.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Family Planning Services and Management for Migrants, National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, for their support in providing the database (the 2013 Migrant Dynamics Monitoring Survey in China) for this study. We also want to thank Emily Greathead and Arnold Ikedichi Okpani for reviewing and improving English language in the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from National Commission of Health and Family Planning, People’s Republic of China. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data.. The data used is, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of National Commission of Health and Family Planning, People’s Republic of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC conceived the study design, conceptualized the problem, and supervised data management and analyses. YJ and HBD provided technical support for the data analysis, revised and edited the manuscript. YTZ wrote the manuscript to which all the authors contributed. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since the study utilized national data from the National Commission of Health and Family Planning, the ethics approval has been exempted by Peking University Institution Review Board.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Ji, Y., Dong, H. et al. The prevalence of smoking, second-hand smoke exposure, and knowledge of the health hazards of smoking among internal migrants in 12 provinces in China: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 18, 655 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5549-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5549-8